dimanche, 15 juin 2014

Kamikazes

L’opposition entre la culture occidentale prônant le libre arbitre et l’obligation de se donner la mort en mission commandée a ouvert la porte à l’irrationalité et au romantisme. Leur dernière nuit était un déchirement, mais tous ont su trouver la force de sourire avant le dernier vol. Kasuga Takeo (86 ans), dans une lettre au docteur Umeazo Shôzô, apporte un témoignage exceptionnel sur les dernières heures des kamikazes : « Dans le hall où se tenait leur soirée d’adieu la nuit précédant leur départ, les jeunes étudiants officiers buvaient du saké froid. Certains avalaient le saké en une gorgée, d’autres en engloutissaient une grande quantité. Ce fut vite le chaos. Il y en avait qui cassaient des ampoules suspendues avec leurs sabres. D’autres qui soulevaient les chaises pour casser les fenêtres et déchiraient les nappes blanches. Un mélange de chansons militaires et de jurons emplissaient l’air. Pendant que certains hurlaient de rage, d’autres pleuraient bruyamment. C’était leur dernière nuit de vie. Ils pensaient à leurs parents et à la femme qu’ils aimaient….Bien qu’ils fussent censés être prêts à sacrifier leur précieuse jeunesse pour l’empire japonais et l’empereur le lendemain matin, ils étaient tiraillés au-delà de toute expression possible…Tous ont décollé au petit matin avec le bandeau du soleil levant autour de la tête. Mais cette scène de profond désespoir a rarement été rapportée. »

Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney, Kamikazes, Fleurs de cerisier et Nationalismes, éditions Hermann, 2013, 580 p., 38 euros.

Ex: http://zentropaville.tumblr.com

00:05 Publié dans Livre, Livre, Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : livre, kamikazes, japon, traditions, traditionalisme, asie, affaires asiatiques |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 12 juin 2014

Qu’est-ce que l’Imperium ?

Qu’est-ce que l’Imperium?

par Charles Mallet

Ex: http://lheurasie.hautetfort.com

A ce titre, ce concept est à l’image de la culture politique et de la pratique du pouvoir des Empereurs Romains : souple, pragmatique, concrète. Il en va de même de la nature du pouvoir impérial, difficile à appréhender et à définir, puisque construit par empirisme (sa nature monarchique n’est cependant pas contestable). En plus de quatre siècles, le pouvoir impérial a su s’adapter aux situations les plus périlleuses (telle la « crise » du IIIe siècle). Rien de commun en effet entre le principat augustéen, système dans lequel l’empereur est le princeps, le prince, primus inter pares, c’est-à-dire premier entre ses pairs de l’aristocratie sénatoriale ; la tétrarchie de Dioclétien (284-305), partage du pouvoir entre quatre empereurs hiérarchisés et l’empire chrétien de Constantin (306-337), dans lesquels l’empereur est le dominus, le maître.

A ce titre, ce concept est à l’image de la culture politique et de la pratique du pouvoir des Empereurs Romains : souple, pragmatique, concrète. Il en va de même de la nature du pouvoir impérial, difficile à appréhender et à définir, puisque construit par empirisme (sa nature monarchique n’est cependant pas contestable). En plus de quatre siècles, le pouvoir impérial a su s’adapter aux situations les plus périlleuses (telle la « crise » du IIIe siècle). Rien de commun en effet entre le principat augustéen, système dans lequel l’empereur est le princeps, le prince, primus inter pares, c’est-à-dire premier entre ses pairs de l’aristocratie sénatoriale ; la tétrarchie de Dioclétien (284-305), partage du pouvoir entre quatre empereurs hiérarchisés et l’empire chrétien de Constantin (306-337), dans lesquels l’empereur est le dominus, le maître. Ainsi, à l’éclatement politique de l’Europe au Moyen Âge et à l’époque Moderne a correspondu un éclatement du pouvoir souverain, de l’imperium. L’idée d’un pouvoir souverain fédérateur n’en n’a pas pour autant été altérée. Il en va de même de l’idée d’une Europe unie, portée par l’Eglise, porteuse première de l’héritage romain. Le regain d’intérêt que connait la notion d’imperium n’est donc pas le fruit d’une passion romantique pour l’antiquité européenne, mais la preuve qu’en rupture avec la conception moderne positiviste de l’histoire, nous regardons les formes d’organisations politiques passées comme autant d’héritages vivants et qu’il nous appartient de nous les réapproprier (les derniers empires héritiers indirects de la vision impériale issue de Rome ont respectivement disparu en 1917 –Empire Russe- et 1918 –Empire Austro-Hongrois et Empire Allemand-). Si ce court panorama historique ne peut prétendre rendre compte de la complexité du phénomène, de sa profondeur, et des nuances nombreuses que comporte l’histoire de l’idée d’imperium ou même de l’idée d’Empire, nous espérons avant tout avoir pu clarifier son origine et son sens afin d’en tirer pour la réflexion le meilleur usage possible. L’imperium est une forme du pouvoir politique souple et forte à la fois, capable de redonner du sens à l’idée de souveraineté, et d’articuler autorité politique continentale et impériale de l’Eurasisme avec les aspirations à la conservation des autonomies et des identités nationales portées par le Nationalisme ou même le Monarchisme. A l’heure où le démocratisme, les droits de l’homme, et le libéralisme entrent dans leur phase de déclin, il nous revient d’opposer une alternative cohérente et fédératrice et à opposer l’imperium au mondialisme.

Ainsi, à l’éclatement politique de l’Europe au Moyen Âge et à l’époque Moderne a correspondu un éclatement du pouvoir souverain, de l’imperium. L’idée d’un pouvoir souverain fédérateur n’en n’a pas pour autant été altérée. Il en va de même de l’idée d’une Europe unie, portée par l’Eglise, porteuse première de l’héritage romain. Le regain d’intérêt que connait la notion d’imperium n’est donc pas le fruit d’une passion romantique pour l’antiquité européenne, mais la preuve qu’en rupture avec la conception moderne positiviste de l’histoire, nous regardons les formes d’organisations politiques passées comme autant d’héritages vivants et qu’il nous appartient de nous les réapproprier (les derniers empires héritiers indirects de la vision impériale issue de Rome ont respectivement disparu en 1917 –Empire Russe- et 1918 –Empire Austro-Hongrois et Empire Allemand-). Si ce court panorama historique ne peut prétendre rendre compte de la complexité du phénomène, de sa profondeur, et des nuances nombreuses que comporte l’histoire de l’idée d’imperium ou même de l’idée d’Empire, nous espérons avant tout avoir pu clarifier son origine et son sens afin d’en tirer pour la réflexion le meilleur usage possible. L’imperium est une forme du pouvoir politique souple et forte à la fois, capable de redonner du sens à l’idée de souveraineté, et d’articuler autorité politique continentale et impériale de l’Eurasisme avec les aspirations à la conservation des autonomies et des identités nationales portées par le Nationalisme ou même le Monarchisme. A l’heure où le démocratisme, les droits de l’homme, et le libéralisme entrent dans leur phase de déclin, il nous revient d’opposer une alternative cohérente et fédératrice et à opposer l’imperium au mondialisme.

00:05 Publié dans Définitions, Théorie politique, Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : imperium, tradition, traditionalisme, empire, notion d'empire, reich, histoire, rome, rome antique, empire romain, définition, théorie politique, politologie, sciences politiques, philosophie politique |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 01 juin 2014

J. Evola: Metafisica del sesso e idealismo magico

00:02 Publié dans Evénement, Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : tradition, traditionalisme, julius evola, métaphysique, métaphysique du sexe, sexualité, italie, événement, idéalisme magique, philosophie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 31 mai 2014

Tradizione e rivoluzione: intervista con Renato Del Ponte

Tradizione e rivoluzione: intervista con Renato Del Ponte

00:05 Publié dans Entretiens, Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : tradition, renato del ponte, julius evola, traditionalisme, italie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 15 mai 2014

Les ressorts psychologiques des pilotes Tokkôtai

Manipulation esthétique et romantisme

Les ressorts psychologiques des pilotes Tokkôtai

Kamikazes, fleurs de cerisiers et nationalismes

Rémy ValatEx: http://metamag.fr

花は桜木人は武士(hana wa sakuragi hito wa bushi).

« La fleur des fleurs est le cerisier, la fleur des hommes est le guerrier. »

Les éditions Hermann ont eu la bonne idée de publier le livre d’Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney, Kamikazes, Fleurs de cerisier et Nationalismes, paru précédemment en langue anglaise aux éditions des universités de Chicago (2002) sous le titre Kamikaze, Cherry Blossoms, and Nationalisms : The Militarization of Aesthetics in Japanese History. La traduction de cette étude magistrale est de Livane Pinet Thélot (revue par Xavier Marie). Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney enseigne l’anthropologie à l'université du Wisconsin ; elle est une spécialiste réputée du Japon. Sa carrière académique est exceptionnelle : elle est présidente émérite de la section de culture moderne à la Bibliothèque du Congrès de Washington, membre de l’Avancées de Paris et de l'Académie américaine des arts et des sciences.

Kamikazes, Fleurs de cerisier et Nationalismes n’est pas une histoire de bataille. L’auteure s’est intéressée aux manipulations esthétiques et symboliques de la fleur de cerisier par les pouvoirs politiques et militaires des ères Meiji, Taishô et Shôwa jusqu’en 1945. La floraison des cerisiers appartient à la culture archaïque japonaise, elle était associée à la fertilité, au renouveau printanier, à la vie. L’éphémère présence de ces fleurs blanches s’inscrivait dans le calendrier des rites agricoles, lesquels culminaient à l’automne avec la récolte du riz, et étaient le prétexte à libations d’alcool de riz (saké) et festivités. Au fil des siècles, les acteurs politiques et sociaux ont octroyé une valeur différente au cerisier : l’empereur pour se démarquer de l’omniprésente culture chinoise et de sa fleur symbole, celle du prunier ; les samouraïs et les nationalistes pour souligner la fragilité de la vie du guerrier, et, surtout pour les seconds, institutionnaliser une esthétique valorisant la mort et le sacrifice. Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney nous révèle l’instrumentalisation des récits, des traditions et des symboles nippons, ayant pour toile de fond et acteurs des cerisiers et des combattants : le Manyôshû (circa 755 ap. JC), un recueil de poèmes mettant en scène les sakimori (garde-frontières en poste au nord de Kyûshû et sur les îles de Tsushima et d’Iki) ont été expurgés des passages trop humains où les hommes exprimaient leur affection pour leurs proches de manière à mettre en avant la fidélité à l’empereur. L’épisode des pilotes tokkôtai survint à la fin de la guerre du Pacifique et atteint son paroxysme au moment où le Japon est victime des bombardements américains et Okinawa envahi. Ces missions suicides ont marqué les esprits (c’était l’un des objectifs de l’état-major impérial) et donné une image négative du combattant japonais, dépeint comme un « fanatique »... Avec une efficacité opérationnelle faible, après l’effet de surprise de Leyte (où 20,8% des navires ont été touchés), le taux des navires coulés ou endommagés serait de 11,6%....Tragique hasard de l’Histoire, la bataille d’Okinawa s’est déroulée au moment de la floraison des cerisiers, donnant une touche romantique à cette irrationnelle tragédie, durant laquelle le Japon va sacrifier la fine fleur de sa jeunesse.

Fine fleur, car ces jeunes hommes, un millier environ, étaient des étudiants provenant des meilleures universités du pays, promus hâtivement officiers-pilotes pour une mission sans retour. 3843 pilotes (estimation maximale incluant toutes les catégories socio-professionnelles et classes d’âge) sont morts en tentant de s’écraser sur un bâtiment de guerre américain. L’étude des journaux intimes de ces jeunes kamikazes, journaux parfois entamés plusieurs années auparavant constitue une source inestimable car elle permet de cerner l’évolution psychologique et philosophique des futurs pilotes. L’analyse, centrée sur 5 cas, révèle que l’intériorisation de la propagande militaire et impériale était imparfaite, individualisée. Toutefois, le panel étudié (5%de la population) est la principale faiblesse de l’argumentation d’Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney (l’auteure aurait eu des difficultés à trouver des sources originales et complètes). Il ressort de son analyse que peu de pilotes, dont aucun n’était probablement volontaire, aurait réellement adhéré à l’idéologie officielle. Ironie, les étudiants-pilotes étaient pétris de culture : la « génération Romain Rolland » (lire notre recension du livre de Michael Lucken, Les Japonais et la guerre).

Fine fleur, car ces jeunes hommes, un millier environ, étaient des étudiants provenant des meilleures universités du pays, promus hâtivement officiers-pilotes pour une mission sans retour. 3843 pilotes (estimation maximale incluant toutes les catégories socio-professionnelles et classes d’âge) sont morts en tentant de s’écraser sur un bâtiment de guerre américain. L’étude des journaux intimes de ces jeunes kamikazes, journaux parfois entamés plusieurs années auparavant constitue une source inestimable car elle permet de cerner l’évolution psychologique et philosophique des futurs pilotes. L’analyse, centrée sur 5 cas, révèle que l’intériorisation de la propagande militaire et impériale était imparfaite, individualisée. Toutefois, le panel étudié (5%de la population) est la principale faiblesse de l’argumentation d’Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney (l’auteure aurait eu des difficultés à trouver des sources originales et complètes). Il ressort de son analyse que peu de pilotes, dont aucun n’était probablement volontaire, aurait réellement adhéré à l’idéologie officielle. Ironie, les étudiants-pilotes étaient pétris de culture : la « génération Romain Rolland » (lire notre recension du livre de Michael Lucken, Les Japonais et la guerre).

L’opposition entre la culture occidentale prônant le libre arbitre et l’obligation de se donner la mort en mission commandée a ouvert la porte à l’irrationalité et au romantisme. Leur dernière nuit était un déchirement, mais tous ont su trouver la force de sourire avant le dernier vol. Kasuga Takeo (86 ans), dans une lettre au docteur Umeazo Shôzô, apporte un témoignage exceptionnel sur les dernières heures des kamikazes : « Dans le hall où se tenait leur soirée d’adieu la nuit précédant leur départ, les jeunes étudiants officiers buvaient du saké froid. Certains avalaient le saké en une gorgée, d’autres en engloutissaient une grande quantité. Ce fut vite le chaos. Il y en avait qui cassaient des ampoules suspendues avec leurs sabres. D’autres qui soulevaient les chaises pour casser les fenêtres et déchiraient les nappes blanches. Un mélange de chansons militaires et de jurons emplissaient l’air. Pendant que certains hurlaient de rage, d’autres pleuraient bruyamment. C’était leur dernière nuit de vie. Ils pensaient à leurs parents et à la femme qu’ils aimaient....Bien qu’ils fussent censés être prêts à sacrifier leur précieuse jeunesse pour l’empire japonais et l’empereur le lendemain matin, ils étaient tiraillés au-delà de toute expression possible...Tous ont décollé au petit matin avec le bandeau du soleil levant autour de la tête. Mais cette scène de profond désespoir a rarement été rapportée. » (pp. 292-293).

Quel sens donner à leur sacrifice ?

Outre celui de protéger leurs proches, l’idée de régénération est forte. Un Japon nouveau, épuré des corruptions de l’Occident (matérialisme, égoïsme, capitalisme, modernité) germerait de leur sublime et suprême offrande. La méconnaissance (source d’interprétations multiples) et l’archaïsme du symbole a, semble-t-il, éveillé et mobilisé des sentiments profonds et primitifs, et pourtant ô combien constitutifs de notre humanité. Ironie encore, ce sont contre des bâtiments américains que viennent périr ces jeunes hommes, ces « bâtiments noirs, venus la première fois en 1853, obligeant le Japon à faire face aux défis de l’Occident et de la mondialisation. Il ne faut pas oublier que l’ultranationalisme japonais est une réponse à ce défi... Le Japon ne s’est pas laissé coloniser comme la Chine ; les guerres de l’opium ont donné à réfléchir aux élites japonaises. Mieux, les Japonais ont su s’armer, réfléchir et chercher le meilleur moyen de retourner les armes de l’agresseur. Le Japon a été un laboratoire intellectuel intense, et le communisme, idéologie sur laquelle la Chine habillera son nationalisme, est un import du pays du Soleil Levant... Ernst Nolte explique les excès du nazisme comme une réaction au danger communiste (La guerre civile européenne) : il en est de même au Japon. La menace des navires américains est un retour à l’acte fondateur du nationalisme nippon expliquerait l’irrationalité des actes de mort volontaire...

Le livre d’Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney, qui professe aux Ėtats-Unis, est remarquable, mais peut-être marqué par l’esprit du vainqueur. « Ce qui est regrettable par-dessus tout, écrit-elle (p. 308), c’est que la majorité de la population ait oublié les victimes de la guerre. Ces dernières sont tombées dans les oubliettes de l’histoire, ont été recouvertes par la clameur des discussions entre les libéraux et l’extrême-droite, au lieu d’être le rappel de la culpabilité de la guerre que chaque Japonais devrait partager ». La culpabilité (la repentance) est une arme politique ne l’oublions pas : une arme qui sert peut-être à garder le Japon sous influence américaine, car même si le Japon s’achemine vers une « normalisation » de sa politique et de ses moyens de défense, l’interdépendance des industries d’armement et de communication ainsi que l’instrumentalisation du débat sur la Seconde Guerre mondiale en Asie entravent le processus d’une totale indépendance politique de ce pays. Si les Japonais devraient partager la culpabilité des victimes de la guerre ? Qui doit partager celles des bombardements de Tôkyô, de Hiroshima et de Nagasaki ? Enfin, on ignore l’état d’esprit de ce qui ont le plus sincèrement adhéré à l’idéologie impériale au point de sacrifier leurs vies pour elle (Nogi Maresuke, Onishi Takijiro, fondateur des escadrilles tokkôtai, pour les plus illustres). Orages d’acier ou À l’Ouest rien de nouveau, deux expériences et deux visions, radicalement opposées, sur une même guerre...

Emiko Ohnuki-Tierney, Kamikazes, Fleurs de cerisier et Nationalismes, éditions Hermann, 2013, 580 p., 38 euros.

00:05 Publié dans Histoire, Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : asie, histoire, tradition, traditionalisme, japon, tokkotai, kamikaze, pilotes suicide, deuxième guerre mondiale, seconde guerre mondiale |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 03 mai 2014

Artaud, Castaneda, Eliade e il viaggio iniziatico

di Chiara Donnini

Fonte: ideeinoltre

Tante altre notizie su www.ariannaeditrice.it

00:05 Publié dans Philosophie, Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : philosophie, antonin arthaud, mircea eliade, castaneda, traditions, traditionalisme |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mercredi, 23 avril 2014

Hercule, un Jésus européen ?

Hercule, un Jésus européen?

par Thomas Ferrier

Ex: http://thomasferrier.hautetfort.com

« Hercules, the legend begins » est enfin sorti sur les écrans français après avoir connu un terrible échec commercial, il y a deux mois, aux Etats-Unis. On pouvait donc craindre le pire, malgré une bande annonce des plus alléchantes. Après avoir vu ce film, que j’ai pour ma part beaucoup apprécié, je m’interroge sur le pourquoi de cette descente en flammes et de ce qui a déplu à la critique.

Bien sûr, dans cette Grèce du XIIIème siècle avant notre ère, il y a de nombreux anachronismes comme des combats de gladiateurs ou encore la conquête de l’Egypte. Si de beaux efforts graphiques ont été faits, on se trouve dans une Grèce de légende, à mi-chemin entre la Grèce mycénienne et la Grèce classique. Et de même, la légende du héros, avec les douze travaux, est absente ou malmenée, alors que de nouveaux éléments s’ajoutent, comme une rivalité entre Héraclès et son frère Iphiclès. Tout cela a pu surprendre un public habitué à ces classiques.

Et pourtant de nombreuses idées audacieuses se sont glissées dans ce film et le rendent passionnant. Ainsi, la vie d’Hercule s’apparente par certains aspects à celle de Jésus. De nombreux films américains, à l’instar de Man of Steel, la comparaison implicite est patente. Dans « Hercules », elle est voulue mais détournée. Alcmène s’unit à Zeus sans que le dieu apparaisse, se manifestant par une tempête accompagnée d’éclairs. Cela ne vous rappelle rien ? De même, Hercule est fouetté et attaché par les deux bras dans une scène rappelant la crucifixion. Mais il en sort vainqueur, brisant ses liens, et écrasant grâce à deux énormes blocs de pierre attachés par des chaînes à ses bras tous ses ennemis. Enfin, il devient concrètement roi à la fin de son aventure, ne se revendiquant pas simplement « roi de son peuple » mais roi véritable.

Bien sûr, ce « Jésus » aux muscles imposants mais sobres, à la pigmentation claire et aux cheveux blonds, n’a pas la même morale. Fils du maître de l’univers, dont il finit par accepter la paternité, Zeus en personne, il tue ses ennemis, jusqu’à son propre père adoptif, combat avec une férocité qui en ferait l’émule d’Arès, et semble quasi insensible à la douleur. Une scène le présente même recevant sur son épée la foudre de Zeus qu’il utilise ensuite comme une sorte de fouet électrique pour terrasser les combattants qui lui font face.

Par ailleurs, la « diversité » est réduite à sa plus petite expression, limitée à des mercenaires égyptiens, crédibles dans leur rôle. Les Grecs en revanche sont tous bien européens, avec des traits parfois nordiques. Il n’est pas question comme dans « Les Immortels » ou « Alexandre » de voir des afro-américains en armure ou jouant les Roxanes. En revanche, on retrouve davantage l’esprit de Troie, l’impiété en moins. En effet, cette fois les athées ont le mauvais rôle à l’instar du roi de Tirynthe Amphitryon. Hercule lui-même, qui ne croit pas dans l’existence des dieux pendant une bonne partie du film, finit par se revendiquer explicitement de la filiation de Zeus et la prouver. En outre, Hercules rappelle par certains côtés le premier Conan, puisque le héros est trahi et fait prisonnier, puis s’illustre dans des combats dans l’arène d’une grande intensité, bondissant tel un fauve pour fracasser le crâne d’un ennemi, mais il reste toujours chevaleresque, protégeant les femmes et les enfants.

A certains moments, le film semble même s’inspirer des traits guerriers qu’un Breker donnait à ses statues. Kellan Lutz n’est sans doute pas un acteur d’une expression théâtrale saisissante mais il est parfaitement dans son rôle. Si les douze travaux se résument à étrangler le lion de Némée, à vaincre de puissants ennemis mais qui demeurent humains, et à reconquérir sa cité, son caractère semi-divin, même si le personnage refuse tout hybris, est non seulement respecté mais amplifié. En ce sens, Hercule apparaît comme un Jésus païen et nordique, mais aussi un Jésus guerrier et vengeur, donc très loin bien sûr du Jésus chrétien. Fils de Dieu, sa morale est celle des Européens, une morale héroïque.

Toutefois, bien sûr, certains aspects modernes apparaissent, comme la relation romantique entre Hercule et Hébé, déesse de la jeunesse qu’il épousera après sa mort dans le mythe grec, et le triomphe de l’amour sur le mariage politique. C’est bien sûr anachronique. Mais « la légende d’Hercule » ne se veut pas un film historique.

Enfin, la morale est sauve puisque dans le film, Héra autorise Zeus à la tromper, alors que dans le mythe classique elle met le héros à l’épreuve par jalousie, afin de faire naître un sauveur. Zeus ne peut donc être « adultère ». Cela donne du sens au nom du héros, expliqué comme « le don d’Héra », alors qu’il signifie précisément « la gloire d’Héra », expression énigmatique quand on connaît la haine de la déesse envers le héros. Pour s’exprimer, Héra pratique l’enthousiasme sur une de ses prêtresses, habitant son corps pour transmettre ses messages. C’est conforme à la tradition religieuse grecque.

Les défauts du film sont mineurs par rapport à ses qualités, graphiques comme scénaristiques, mais ce qui a dû nécessairement déranger c’est qu’il est trop païen, trop européen, trop héroïque, qu’il singe le christianisme pour mieux s’y opposer. Le fils de Dieu est marié et a un enfant (à la fin du film). Le fils de Dieu n’accepte pas d’être emmené à la mort mais triomphe de ses bourreaux. Le fils de Dieu devient « roi des Grecs ». Enfin le fils de Dieu apparaît comme tel aux yeux de tous et n’est pas rejeté par son propre peuple. Ce film ne pouvait donc que déranger une société américaine qui va voir des films où Thor lance la foudre, où Léonidas et ses « 300 » combattent jusqu’à la mort avec une ironie mordante, mais qui reste très chrétienne, très puritaine et hypocrite.

Thomas FERRIER (LBTF/PSUNE)

00:05 Publié dans Cinéma, Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : herakles, hercule, mythologie, mythe, religion, traditions, mythologie grecque, grèce antique, antiquité grecque, hellenisme, film, cinéma, 7ème art |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 15 avril 2014

Iconografia e simboli del potere imperiale

Iconografia e simboli del potere imperiale

Ex: http://www.centrostudilaruna.it

Il filosofo tedesco Ernest Cassirer ebbe ad affermare che l’uomo è “animal symbolicum”, “animale simbolico”, nella sua opera Saggi sull’uomo scriverà infatti: «La ragione è un termine assai inadeguato per comprendere tutte le forme della vita culturale dell’uomo in tutta la loro ricchezza e varietà. Ma tutte queste forme sono forme simboliche. Per conseguenza, invece di definire l’uomo animal rationale, possiamo definirlo animal symbolicum. Così facendo indichiamo ciò che specificamente lo distingue e possiamo capire la nuova strada che si è aperta all’uomo, la strada verso la civiltà.» (1)

Il filosofo tedesco Ernest Cassirer ebbe ad affermare che l’uomo è “animal symbolicum”, “animale simbolico”, nella sua opera Saggi sull’uomo scriverà infatti: «La ragione è un termine assai inadeguato per comprendere tutte le forme della vita culturale dell’uomo in tutta la loro ricchezza e varietà. Ma tutte queste forme sono forme simboliche. Per conseguenza, invece di definire l’uomo animal rationale, possiamo definirlo animal symbolicum. Così facendo indichiamo ciò che specificamente lo distingue e possiamo capire la nuova strada che si è aperta all’uomo, la strada verso la civiltà.» (1)

Come ogni altro fenomeno umano, anche la politica, nel senso più alto del termine, è da sempre stata soggetta ad un processo di simbolizzazione. Ciò è riscontrabile soprattutto attraverso lo studio della scienza araldica, o dell’iconografia, sia del potere temporale che di quello spirituale, spesso in passato strettamente connessi.

Nell‘iconografia occidentale, ad esempio, l’Imperatore è spesso stato accostato ai significati simbolici dell’aquila, in quanto ritenuto investito dall’alto, per la sua peculiarità di vedere oltre, di essere in qualche modo un chiaro-veggente, un illuminato, qualità queste attribuite tradizionalmente al rapace. Nel Bestiaire di Philippe de Thaon del 1126, infatti, si leggono questi versi sull’aquila: «L’aquila è la regina degli uccelli; essa mostra un esempio molto bello. Giustamente in latino la chiamiamo “chiaro-veggente”, perché guarda il sole quando è più luminoso e sebbene lo guardi fissamente, tuttavia non distoglie lo sguardo» (2).

Il simbolo dell’aquila fu signum delle legioni di Roma, inoltre proprio sotto forma di aquila si pensava che le anime dei Cesari liberatesi del corpo assurgessero all’immortalità solare. L’aquila era altresì ritenuta sacra al dio del cielo e padre degli dèi Giove. Scriverà Julius Evola che “fra gli stessi Aztechi si vede figurar l’aquila a indicare il luogo per la capitale del nuovo impero”, e che “il ba, concepito come la parte dell’essere umano destinata ad esistenza eterna celeste in stati di gloria, nei geroglifici egizi è figurato spesso da uno sparviero, equivalente egizio dell’aquila”. Inoltre “Nei Rg-Veda l’aquila porta ad Indra la mistica bevanda che lo costituirà a signore degli déi” (3).

Il simbolo dell’aquila fu signum delle legioni di Roma, inoltre proprio sotto forma di aquila si pensava che le anime dei Cesari liberatesi del corpo assurgessero all’immortalità solare. L’aquila era altresì ritenuta sacra al dio del cielo e padre degli dèi Giove. Scriverà Julius Evola che “fra gli stessi Aztechi si vede figurar l’aquila a indicare il luogo per la capitale del nuovo impero”, e che “il ba, concepito come la parte dell’essere umano destinata ad esistenza eterna celeste in stati di gloria, nei geroglifici egizi è figurato spesso da uno sparviero, equivalente egizio dell’aquila”. Inoltre “Nei Rg-Veda l’aquila porta ad Indra la mistica bevanda che lo costituirà a signore degli déi” (3).

Quando Costantino trasferì la sede imperiale da Roma a Costantinopoli l’aquila bicipite divenne simbolo dell’intero territorio dell’Impero Romano d’Occidente e d’Oriente, stante a rappresentare le due capitali dell’Impero. L’aquila bizantina sarà adottata, in seguito, da Mosca, in qualità di nuova Costantinopoli. Per l’Impero Russo l’aquila bicipite stava a simboleggiare i poteri temporale e spirituale riuniti nell’unica persona dello zar. In seguito le due teste dell’aquila russa passarono a simboleggiare le due parti del continente, fra Europa ed Asia, sulle quali si estendeva il territorio russo. In Occidente, invece, l’aquila bicipite, nera in campo dorato, divenne il simbolo del Sacro Romano Imperatore; il primo ad adottarla in questa forma fu Ludovico il Bavaro nel 1345 e, più tardi, l’Imperatore Sigismondo quando ascese al trono imperiale nel 1410.

Un altro dei simboli più rappresentativi dell’Impero (oltre che del Papato) è il c.d. globo crucigero (globus cruciger): una sfera con in cima apposta una croce. Esso rappresenta il dominio di Cristo (la croce) sul cosmo (la sfera), ed è, inoltre, presente sulla tiara papale, essendo il Papa considerato “padre dei principi e dei re, rettore del mondo, vicario in terra di Cristo”. Altresì la croce, quale doppia congiunzione di punti diametralmente opposti, rappresenta il simbolo dell’unità degli estremi, ad esempio il cielo e la terra. In essa si congiungono tempo e spazio e per ciò, ancor prima dell’avvento del cristianesimo, fu considerata come simbolo universale della mediazione. La croce, per ciò stesso, diviene emblema dell’Imperatore per la sua funzione di mediatore fra Dio e gli uomini, in quanto detentore di un potere temporale assunto per mandato divino. Il Globo terrestre sormontato dalla Croce, inoltre, è l’insegna del potere imperiale iniziaticamente considerato, dell’imperio esercitato sull’Anima del Mondo, ossia sul fluido vitale universale che anima i corpi siderali: secondo un’antica tradizione chi riesce a coagulare tale fluido e a dissolverne a volontà le coagulazioni, comanda all’Anima del Mondo e detiene il supremo potere magico.

Altri simboli connessi al potere e all’autorità regale ed imperiale sono lo scettro, legato da analogia con l’“asse del mondo” (per quanto concerne l’Oriente si ricordi il complementare simbolo del vajra o dorje della tradizione buddhista) ed il trono, legato al “polo” e al “centro immobile”. Similmente in Oriente alla figura del chakravartin (sovrano universale) è connesso l’ancestrale simbolo dello swastika, avente anch’esso un significato “polare”.

Una parte centrale nell’ampio spettro della simbologia imperiale è rivestita dal simbolo del Sole. Il Sole, astro luminoso che dà vita, luce e calore è l’epifania suprema del divino. Così si esprimerà Dante sulla simbologia solare per rappresentare il divino: «non esiste cosa visibile, in tutto il mondo, più degna del sole di fungere da simbolo di Dio, poiché esso illumina con vita visibile prima se stesso, poi tutti i corpi celesti e terreni». Il Sole rappresenta l’Imperatore, investito del principio di autorità massima ed universale, ma anche detentore della più elevata nobiltà d’animo. A tal proposito Mircea Eliade affermò che «sarebbe bene insistere sull’affinità della teologia solare con le élites, siano sovrani, eroi, iniziati o filosofi». Anche in Giappone al potere imperiale è accostato il simbolismo solare, quello della dea Amaterasu ōmikami, Dea del Sole e progenitrice della dinastia regnante. Il Sole è altresì emblema del Re del Mondo, e Cristo è designato dalla liturgia cattolica col titolo di Sol Justitiae: il Verbo è effettivamente il “Sole spirituale”, cioè il vero “Centro del Mondo”. Il simbolismo solare per indicare Cristo è molto adoperato nella Bibbia, inoltre, presso i primi cristiani Cristo è raffigurato non come un essere dalle fattezze umane, ma come un sole fiammeggiante: non a caso il monogramma IHS sormontato da una croce e posto dentro una razza fiammante è uno dei più comuni cristogrammi. Anche al giorno d’oggi il simbolismo del Sole per indicare il Cristo è molto adoperato, basti pensare agli ostensori, aventi per lo più la forma di disco solare. Curiosamente il simbolismo solare è attribuito anche ad un’altra figura soterica, quella del principe Siddhārtha Gautama, il Buddha storico, spesso rappresentato nell’iconografia tradizionale recante dietro il capo il disco solare.

Una parte centrale nell’ampio spettro della simbologia imperiale è rivestita dal simbolo del Sole. Il Sole, astro luminoso che dà vita, luce e calore è l’epifania suprema del divino. Così si esprimerà Dante sulla simbologia solare per rappresentare il divino: «non esiste cosa visibile, in tutto il mondo, più degna del sole di fungere da simbolo di Dio, poiché esso illumina con vita visibile prima se stesso, poi tutti i corpi celesti e terreni». Il Sole rappresenta l’Imperatore, investito del principio di autorità massima ed universale, ma anche detentore della più elevata nobiltà d’animo. A tal proposito Mircea Eliade affermò che «sarebbe bene insistere sull’affinità della teologia solare con le élites, siano sovrani, eroi, iniziati o filosofi». Anche in Giappone al potere imperiale è accostato il simbolismo solare, quello della dea Amaterasu ōmikami, Dea del Sole e progenitrice della dinastia regnante. Il Sole è altresì emblema del Re del Mondo, e Cristo è designato dalla liturgia cattolica col titolo di Sol Justitiae: il Verbo è effettivamente il “Sole spirituale”, cioè il vero “Centro del Mondo”. Il simbolismo solare per indicare Cristo è molto adoperato nella Bibbia, inoltre, presso i primi cristiani Cristo è raffigurato non come un essere dalle fattezze umane, ma come un sole fiammeggiante: non a caso il monogramma IHS sormontato da una croce e posto dentro una razza fiammante è uno dei più comuni cristogrammi. Anche al giorno d’oggi il simbolismo del Sole per indicare il Cristo è molto adoperato, basti pensare agli ostensori, aventi per lo più la forma di disco solare. Curiosamente il simbolismo solare è attribuito anche ad un’altra figura soterica, quella del principe Siddhārtha Gautama, il Buddha storico, spesso rappresentato nell’iconografia tradizionale recante dietro il capo il disco solare.

Altro simbolo che accomuna il Cristo e il grande Filosofo indiano è quello del leone: il supremo insegnamento del Buddha infatti sarà indicato come il “Ruggito del leone”, ed un leone è anche il simbolo della tribù di Giuda descritta nell’Antico Testamento, dalla quale discendeva Gesù Cristo. Il leone è universalmente considerato quale simbolo di regalità, di potenza e di nobiltà, è l’animale re della Savana per i popoli dell’Africa subsahariana. Nella tradizione islamica, l’Imam Alì, nominato direttamente dal Profeta Maometto assunse gli epiteti di Ghadanfar, leone, o Asadullah, leone di Dio. Nell’astrologia il segno zodiacale del Leone è il domicilio del Sole. I leoni sono stati a lungo venerati nel Vicino e nell’Estremo Oriente e furono utilizzati dai vari governanti come simboli del potere regale, proprio come lo erano in Europa: il leone, con la sua fama di animale dotato di gran forza, di coraggio, di nobiltà, così conforme all’ideale della cavalleria medievale fu utilizzarlo come figura ornamentale sulle armi dei Franchi (Merovingi e Carolingi). Mentre in Inghilterra l’introduzione del leone quale simbolo araldico è da attribuirsi ad Enrico II, che adottò uno stemma rosso con un leone rampante d’oro. Per il suo coraggio ed eroismo Riccardo I d’Inghilterra fu insignito dell’epiteto “Cuor di Leone”. Leone fu inoltre il nome di molti imperatori e papi.

Note

(1) Ernest Cassirer, Saggi sull’uomo, Mimesis, Milano, 2011.

(2) Le Bestiaire, Éd. Emmanuel Walberg, Genève, Slatkine Reprints, 1970.

(3) Julius Evola, Rivolta contro il mondo moderno, Edizioni Mediterranee, Roma, 1998.

00:05 Publié dans Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : traditions, impérialité, empire, saint-empire, symbolique, mythes |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 14 avril 2014

Geopolítica, geografía sagrada, geofilosofía

por Claudio Mutti

Ex: http://paginatransversal.wordpress.com

De acuerdo con una definición integral, que intenta sintetizar aquellas proporcionadas por diversos estudiosos, la geopolítica puede ser considerada como “el estudio de las relaciones internacionales en una perspectiva espacial y geográfica, en el que se toman en cuenta la influencia de los factores geográficos sobre la política exterior de los Estados y la rivalidad de poder sobre territorios en disputa entre dos o más Estados, o entre diferentes grupos o movimientos políticos armados” (1).

Por cuán grande sea el peso atribuido a los factores geográficos, aún sigue existiendo la relación de la geopolítica con la doctrina del Estado, por lo que es natural plantearse una interrogante que hasta el momento no parece haber sido tema de reflexión de los estudiosos. La pregunta es la siguiente: ¿Sería posible aplicar también a la geopolítica la famosa afirmación de Carl Schmitt, según la cual “todos los conceptos sobresalientes de la moderna doctrina del Estado son conceptos teológicos secularizados”? (2) En otras palabras, ¿Es posible suponer que la misma geopolítica represente un eco moderno, si no una derivación secularizada de los conceptos teológicos vinculados con la “geografía sagrada”?

Si así fuese, la geopolítica se encontraría en una situación similar no sólo como la descrita sobre la “ciencia moderna del Estado”, sino también con la generalidad de la ciencia moderna. Para ser más explícito, recurramos a una cita de René Guénon: “Queriendo separar radicalmente las ciencias de todo principio superior, so pretexto de asegurar su independencia, la concepción moderna les quita toda significación profunda, e inclusive todo interés verdadero desde el punto de vista del conocimiento, y ella no puede desembocar más que en un callejón sin salida, puesto que las encierra en un dominio irremediablemente limitado” (3).

En cuanto atañe particularmente a la “geografía sagrada”, con la cual -según nuestra hipótesis- se relacionaría de algún modo la geopolítica, es de igual manera Guénon quién nos proporciona una sintética indicación al respecto: “Ahora bien, efectivamente existe una «geografía sagrada» o tradicional que los modernos ignoran tan completamente como los restantes conocimientos del mismo género; existe un simbolismo geográfico en la misma medida que existe un simbolismo histórico y es el valor simbólico de las cosas lo que les da su significado profundo dado que así queda establecida su correspondencia con las realidades de orden superior; no obstante, para que esta correspondencia quede determinada de forma efectiva, es preciso ser capaz de un modo u otro de percibir en las propias cosas el reflejo de tales realidades. Así ocurre que existen lugares particularmente aptos para servir de «soporte» a la acción de «las influencias espirituales» y este es el fundamento que siempre ha tenido el establecimiento de ciertos «centros» tradicionales principales o secundarios, cuyos más claros exponentes fueron los «oráculos» de la Antigüedad así como los lugares de peregrinación; también existen otros lugares particularmente propicios a la manifestación de «influencias» de un carácter completamente opuesto y pertenecientes a las regiones más inferiores del ámbito de lo sutil” (4).

Se ha dicho que rastros de la “geografía sagrada” son reconocibles en algunas características de las nociones geopolíticas, por lo tanto, éstas podrían ser consideradas schmittianamente como “conceptos teológicos secularizados”. Consideremos, por ejemplo, los términos mackinderianos como Heartland y pivot area, los cuales, invocan de manera explicita el simbolismo del corazón y el simbolismo axial, reproducen de alguna manera la idea de “Centro del Mundo” que los antiguos representaban por medio de una variedad de símbolos, geográficos y no geográficos. Muchas veces se ha ofrecido la ocasión para observar que, si la ciencia de las religiones ha demostrado que el homo religiosus “aspira a vivir lo más cerca posible del Centro del Mundo y sabe que su país se encuentra efectivamente en medio de la tierra” (5), esta concepción no ha desaparecido con la visión “arcaica” del mundo, al contrario, ha sobrevivido en una forma más o menos consciente en contextos históricos y culturales más recientes (6).

Por otra parte, dentro de los términos geográficos y geopolíticos existen algunos que las culturas tradicionales han utilizado para describir la realidad perteneciente a la esfera espiritual. Este es el caso del término polo, que en el léxico del esoterismo islámico indica el vértice de la jerarquía iniciática (al-qutb); es el caso de istmo, que en la forma árabe (al-barzakh) indica aquel mundo intermedio al que también se refiere la expresión geográfica de origen coránica: “la confluencia de dos mares” (majma’ al-bahrayn), “confluencia, es decir, del mundo de las Ideas puras con el mundo de los objetos sensibles” (7).

Pero también el concepto de Eurasia puede ser asignado a la categoría de “conceptos teológicos secularizados”.

De hecho, el más antiguo texto teológico de los Griegos, la Teogonía de Hesíodo, nos cuenta que: “Europa ( … ) y Asia” (8) constan entre las hijas de Océano y Tetis, “una sagrada estirpe de hijas (thygatéron hieron genos) que por la tierra se encargan de la crianza de los hombres, en compañía del soberano Apolo y de los Ríos, y han recibido de Zeus este destino” (9).

Cabe destacar que entre las hermanas Europa y Asia también figura Perseis, cuyo nombre está significativamente relacionado no sólo con el griego Perseo, sino también con Perses, su hijo y progenitor de los persas. Escuchemos ahora al teólogo de la historia: “Pero cuando Perseo, hijo de Dánae y de Zeus, llegó al reino de Cefeo, hijo de Belo, y se casó con su hija Andrómeda, tuvo en ella un hijo a quien puso el nombre de Perses, y le dejó allí, porque Cefeo no había tenido hijo varón. De este Perses, pues, tomaron el nombre” (10).

El estrecho parentesco entre Asia con Europa es finalmente proclamado también por el teólogo de la tragedia, quien en la parodia de los Persianos nos presenta a Persia y Grecia como dos “hermanas de sangre, de una misma estirpe (kasignéta génous tautou)” (11), mostrándonos “absolutamente distintas (las dos que, en Herodoto, no pueden evitar ir a la guerra) como de raíz inseparables” (12). Este es el comentario de Massimo Cacciari, para quien la imagen esquilea, representativa de la radical conexión de Europa y Asia, le ha proporcionado el motivo para crear una “geofilosofia de Europa”.

Fabio Falchi intenta ir más allá: en este volumen, él traza las líneas de una “geofilosofía de Eurasia”. Acogiendo la perspectiva corbiniana de Eurasia, cual lugar ontológico teofanico (13), el autor aspira para hacer de la posición geofilosófica el grado de pasaje para aquella “geosófica”, lo cual es completamente inteligible si, y sólo si, se coloca en relación con la perspectiva metafísica” (14).

(Traducción: Francisco de la Torre)

1 Emidio Diodato, Che cos’è la geopolitica, Carocci, Roma 2011.

2 Carl Schmitt, Teología política. Editorial Struhart & Cía. Buenos Aires, 1985, p. 95.

3 René Guénon, La Crisis del Mundo Moderno. Ediciones Obelisco. Barcelona. 1982, p. 44.

4 René Guénon, El Reino de la Cantidad y los Signos de los Tiempos. Ediciones Paidós Ibérica S.A.. Barcelona. 1997, p. 122 y 123.

5 Mircea Eliade, Lo sagrado y lo profano, Guadarrama/Punto Omega, Madrid, 1981, p. 43.

6 Claudio Mutti, La funzione eurasiatica dell’Iran, “Eurasia”, 2, 2012, p. 176; Geopolitica del nazionalcomunismo romeno, in: Marco Costa, Conducǎtor. L’edificazione del socialismo romeno, Edizioni all’insegna del Veltro, Parma 2012.

7 Henry Corbin, Templo y contemplación. Ensayos sobre el Islam iranio. Editorial Trotta, Madrid, 2003, p. 262. Sobre el barzakh, cfr. Glauco Giuliano, L’immagine del tempo in Henry Corbin, Mimesis, Milano-Udine 2009, pp. 97-123.

11 Esquilo, Los persas, 185-186. Sobre esta imagen: cfr. C. Mutti, L’Iran in Europa, “Eurasia”, 1, 2008, pp. 33-34.

12 Massimo Cacciari, Geofilosofia dell’Europa, Adelphi, Milano 1994, p. 19.

13 “Eurasia es, hoy y para nosotros, la modalidad geográfica-geosófica del Mundus imaginalis” (Glauco Giuliano, L’immagine del tempo in Henry Corbin, cit., p. 40).

14 Glauco Giuliano, Tempus discretum. Henry Corbin all’Oriente dell’Occidente, Edizioni Torre d’Ercole, Travagliato (Brescia) 2012, p. 16.

00:06 Publié dans Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : claudio mutti, géopolitique, géographie, géographie sacrée, géophilosophie, philosophie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 12 avril 2014

Friedrich Georg Jünger: The Titans and the Coming of the Titanic Age

Friedrich Georg Jünger:

The Titans and the Coming of the Titanic Age

Tom Sunic

Translated from the German and with an Introduction by Tom Sunic

Friedrich Georg Jünger (1898-1977)

Introduction: Titans, Gods and Pagans by Tom Sunic

Below is my translation of several passages from the last two chapters from Friedrich Georg Jünger’s little known book, Die Titanen, 1943, 1944 (The Titans). Only the subtitles are mine. F.G. Jünger was the younger brother of Ernst Jünger who wrote extensively about ancient Greek gods and goddesses. His studies on the meaning of Prometheism and Titanism are unavoidable for obtaining a better understanding of the devastating effects of the modern belief in progress and the role of “high-tech” in our postmodern societies. Outside the German-speaking countries, F.G. Jünger’s literary work remains largely unknown, although he had a decisive influence on his renowned brother, the essayist Ernst Jünger. Some parts of F.G Jünger’s other book,Griechische Götter (1943) (Greek Gods), with a similar, if not same topic, and containing also some passages from Die Titanen, were recently translated into French (Les Titans et les dieux, 2013).

In the footsteps of Friedrich Nietzsche and along with hundreds of German philosophers, novelists, poets and scientists, such as M. Heidegger, O. Spengler, C. Schmitt, L. Clauss, Gottfried Benn, etc., whose work became the object of criminalization by cultural Bolsheviks and by the Frankfurt School in the aftermath of WWII, F. G. Jünger can also be tentatively put in the category of “cultural conservative revolutionaries” who characterized the political, spiritual and cultural climate in Europe between the two world wars.

Ancient European myths, legends and folk tales are often derided by some scholars, including some Christian theologians who claim to see in them gross reenactments of European barbarism, superstition and sexual promiscuity. However, if a reader or a researcher immerses himself in the symbolism of the European myths, let alone if he tries to decipher the allegorical meaning of diverse creatures in the myths, such as for instance the scenes from the Orphic rituals, the hellhole of Tartarus, or the carnage in the Nibelungen saga, or the final divine battle in Ragnarök, then those mythical scenes take on an entirely different meaning. After all, in our modern so-called enlightened and freedom-loving liberal societies, citizens are also entangled in a profusion of bizarre infra-political myths, in a myriad of weird hagiographic tales, especially those dealing with World War II vicitmhoods, as well as countless trans-political, multicultural hoaxes enforced under penalty of law. Therefore, understanding the ancient European myths means, first and foremost, reading between the lines and strengthening one’s sense of the metaphor.

There persists a dangerous misunderstanding between White nationalists professing paganism vs. White nationalists professing Christian beliefs. The word “paganism” has acquired a pejorative meaning, often associated with childish behavior of some obscure New Age individuals carrying burning torches or reading the entrails of dead animals. This is a fundamentally false conception of the original meaning of paganism. “Pagans,” or better yet polytheists, included scores of thinkers from antiquity, such as Seneca, Heraclites, Plato, etc. who were not at all like many modern self-styled and self-proclaimed “pagans” worshipping dogs or gazing at the setting sun. Being a “pagan” denotes a method of conceptualizing the world beyond the dualism of “either-or.” The pagan outlook focuses on the rejection of all dogmas and looks instead at the notion of the political or the historical from diverse and conflicting perspectives. Figuratively speaking, the plurality of gods means also the plurality of different beliefs and different truths. One can be a good Christian but also a good “pagan.” For that matter even the “pagan” Ernst Jünger, F.G. Jünger’s older brother, had a very Catholic burial in 1998.

When F.G Jünger’s published his books on the Titans and the gods, in 1943 and in 1944, Germany lay in ruins, thus ominously reflecting F.G. Jünger’s earlier premonitions about the imminent clash of the Titans. With gods now having departed from our disenchanted and desacralized White Europe and White America, we might just as well have another look at the slumbering Titans who had once successfully fought against Chaos, only to be later forcefully dislodged by their own divine progeny.

Are the dozing Titans our political option today? F.G. Jünger’s book is important insofar as it offers a reader a handy manual for understanding a likely reawakening of the Titans and for decoding the meaning of the new and fast approaching chaos.

* * *

THE TITANS: CUSTODIANS OF LAW AND ORDER

….The Titans are not the Gods even though they generate the Gods and relish divine reverence in the kingdom of Zeus. The world in which the Titans rule is a world without the Gods. Whoever desires to imagine a kosmos atheos, i.e. a godless cosmos, that is, a cosmos not as such as depicted by natural sciences, will find it there. The Titans and the Gods differ, and, given that their differences are visible in their behavior toward man and in view of the fact that man himself experiences on his own as to how they rule, man, by virtue of his own experience, is able to make a distinction between them.

Neither are the Titans unrestrained power hungry beings, nor do they scorn the law; rather, they are the rulers over a legal system whose necessity must never be put in doubt. In an awe-inspiring fashion, it is the flux of primordial elements over which they rule, holding bridle and reins in their hands, as seen inHelios. They are the guardians, custodians, supervisors and the guides of the order. They are the founders unfolding beyond chaos, as pointed out by Homer in his remarks about Atlas who shoulders the long columns holding the heavens and the Earth. Their rule rules out any confusion, any disorderly power performance. Rather, they constitute a powerful deterrent against chaos.

The Titans and the Gods match with each other. Just as Zeus stands in forKronos, so does Poseidon stand in opposition to Oceanus, or for that matterHyperion and his son Helios in opposition to Apollo, or Coeus and Phoebe in opposition to Apollo and Artemis, or Selene in opposition to Artemis.

THE TITANS AGAINST THE GODS

What distinguishes the kingdom of Kronos from the kingdom of Zeus? One thing is for certain; the kingdom of Kronos is not a kingdom of the son. The sons are hidden in Kronos, who devoured those he himself had generated, the sons being now hidden in his dominion, whereas Zeus is kept away from Kronos by Rhea, who hides and raises Zeus in the caverns. And given that Kronos comports himself in such a manner his kingdom will never be a kingdom of the father. Kronos does not want to be a father because fatherhood is equivalent with a constant menace to his rule. To him fatherhood signifies an endeavor and prearrangement aimed at his downfall.

What does Kronos want, anyway? He wants to preserve the cycle of the status quo over which he presides; he wants to keep it unchanged. He wants to toss and turn it within himself from one eon to another eon. Preservation and perseverance were already the hallmark of his father. Although his father Uranusdid not strive toward the Titanic becoming, he did, however, desire to continue his reign in the realm of spaciousness. Uranus was old, unimaginably old, as old as metal and stones. He was of iron-like strength that ran counter to the process of becoming. But Kronos is also old. Why is he so old? Can this fluctuation of the Titanic forces take on at the same time traits of the immovable and unchangeable? Yes, of course it can, if one observes it from the perspective of the return, or from the point of view of the return of the same. If one attempts it, one can uncover the mechanical side in this ceaseless flux of the movement. The movement unveils itself as a rigid and inviolable law.

THE INFINITE SADNESS OF THE TITANS

How can we describe the sufferings of the Titans? How much do they suffer anyway, and what do they suffer from? The sound of grief uttered by the chainedPrometheus induces Hermes to derisive remarks about the same behavior which is unknown to Zeus. In so far as the Titans are in the process of moving, we must therefore also conceive of them as the objects of removal. Their struggle is onerous; it is filled with anxiety of becoming. And their anxiety means suffering. Grandiose things are being accomplished by the Titans, but grandiose things are being imposed on them too. And because the Titans are closer to chaos than Gods are, chaotic elements reveal themselves amidst them more saliently. No necessity appears as yet in chaos because chaos has not yet been measured off by any legal system. The necessity springs up only when it can be gauged by virtue of some lawfulness. This is shown in the case of Uranus and Kronos. The necessary keeps increasing insofar as lawfulness increases; it gets stronger when the lawful movements occur, that is, when the movements start reoccurring over and over again.

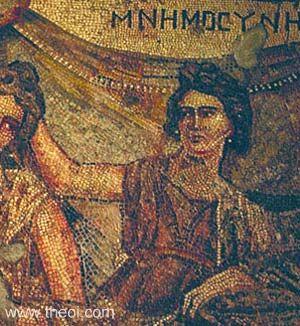

Mnemosyne (The Titaness of Memory) (mosaic, 2nd century AD)

Among the Titanesses the sadness is most visible in the grief of Rhea whose motherhood was harmed. Also in the mourning ofMnemosyne who ceaselessly conjures up the past. The suffering of this Titaness carries something of sublime magnificence. In her inaccessible solitude, no solace can be found. Alone, she must muse about herself — a dark image of the sorrow of life. The suffering of the Titans, after their downfall, reveals itself in all its might. The vanquished Titan represents one of the greatest images of suffering. Toppled, thrown down under into the ravines beneath the earth, sentenced to passivity, the Titan knows only how to carry, how to heave and how to struggle with the burden — similar to the burden carried by the Caryatids.

THE SELF-SUFFICIENT GODS

The Olympian Gods, however, do not suffer like the Titans. They are happy with themselves; they are self-sufficient. They do not ignore the pain and sufferings of man. They in fact conjure up these sufferings, but they also heal them. In Epicurean thought, in the Epicurean world of happiness, we observe the Gods dwelling in-between-the-worlds, divorced from the life of the earth and separated from the life of men, to a degree that nothing can ever reach out to them and nothing can ever come from them. They enjoy themselves in an eternal halcyon bliss that cannot be conveyed by words.

The idea of the Gods being devoid of destiny is brought out here insofar as it goes well beyond all power and all powerlessness; it is as if the Gods had been placed in a deepest sleep, as if they were not there for us. Man, therefore, has no need to think of them. He must only leave them alone in their blissful slumber. But this is a philosophical thought, alien to the myth.

Under Kronos, man is part of the Titanic order. He does not stand yet in the opposition to the order — an opposition founded in the reign of Zeus. He experiences now the forces of the Titans; he lives alongside them. The fisherman and boatman venturing out on the sea are in their Titanic element. The same happens with the shepherd, the farmer, the hunter in their realm. Hyperion, Helios and Eos determine their days, Selene regulates their nights. They observe the running Iris, they see the Horae dancing and spinning around throughout the year. They observe the walk of the nymphs Pleiades and Hyadesin the skies. They recognize the rule of the great Titanic mothers, Gaia, Rhea, Mnemosyne and that of Gaia-Themis. Above all of them rules and reigns the old Kronos, who keeps a record of what happens in the skies, on the earth, and in the waters.

TITANIC NECESSITY VS. DIVINE DESTINY

The course of human life is inextricably linked to the Titanic order. Life makes one whole with it; the course of life cannot be divorced from this order. It is the flow of time, the year’s course, the day’s course. The tides and the stars are on the move. The process resembles a ceaseless flow of the river. Kronos reigns over it and makes sure it keeps returning. Everything returns and everything repeats itself — everything is the same. This is the law of the Titans; this is their necessity. In their motion a strict cyclical order manifests itself. In this order there is a regular cyclical return that no man can escape. Man’s life is a reflection of this cyclic order; it turns around in a Titanic cycle of Kronos.

Man has no destiny here, in contrast to the demigods and the heroes who all have it. The kingdom of Zeus is teeming with life and deeds of heroes, offering an inexhaustible material to the songs, to the epics and to the tragedies. In the kingdom of Kronos, however, there are no heroes; there is no Heroic Age. For man, Kronos, and the Titans have no destiny; they are themselves devoid of destiny. Does Helios, does Selene, does Eos have a destiny? Wherever the Titanic necessity rules, there cannot be a destiny. But the Gods are also deprived of destiny wherever divine necessity prevails, wherever man grasps the Gods in a fashion that is not in opposition to them. But a man whom the Gods confront has a destiny. A man whom the Titans confront perishes; he succumbs to a catastrophe.

We can say, however, that whatever happens to man under the rule of the Titans is a lot easier than under the rule of the Gods. The burden imposed on man is much lighter.

* * *

What happens when the Gods turn away from man and when they leave him on his own? Wherever they make themselves unrecognizable to man, wherever their care for man fades away, wherever man’s fate begins and ends without them, there always happens the same thing. The Titanic forces return and they validate their claims to power. Where no Gods are, there are the Titans. This is a relationship of a legal order which no man can escape wherever he may turn to. The Titans are immortal. They are always there. They always strive to reestablish their old dominion of their foregone might. This is the dream of the Titanic race of the lapetos, and all the Iapetides who dream about it. The earth is penetrated and filled up with the Titanic forces. The Titans sit in ambush, on the lookout, ready to break out and break up their chains and restore the empire of Kronos.

TITANIC MAN

What is Titanic about man? The Titanic trait occurs everywhere and it can be described in many ways. Titanic is a man who completely relies only upon himself and has boundless confidence in his own powers. This confidence absolves him, but at the same time it isolates him in a Promethean mode. It gives him a feeling of independence, albeit not devoid of arrogance, violence, and defiance. Titanic is a quest for unfettered freedom and independence. However, wherever this quest is to be seen there appears a regulatory factor, a mechanically operating necessity that emerges as a correction to such a quest. This is the end of all the Promethean striving, which is well known to Zeus only. The new world created by Prometheus is not.

Dr. Tom Sunic is a former political science professor, author and a Board member of the American Freedom Party. He is the author of Against Democracy and Equality; The European New Right.

00:05 Publié dans Nouvelle Droite, Philosophie, Révolution conservatrice, Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : friedrich-georg jünger, tomislav sunic, philosophie, révolution conservatrice, allemagne, nouvelle droite, mythologie, mythes, traditions |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 23 mars 2014

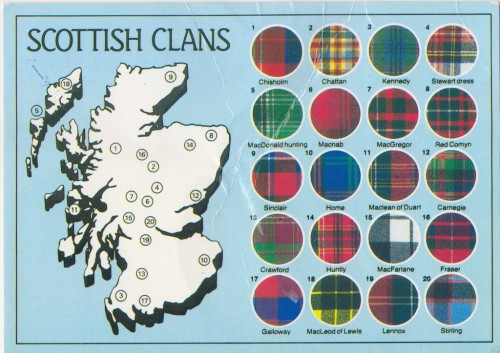

The Clan vs. Modern, State-Dependent “Individualism”

The Clan vs. Modern, State-Dependent “Individualism”

By Jack Donovan

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com

Writing for Cato Unbound, Mark Weiner, author of The Rule of the Clan [2], recently made several correct observations about the problem of reconciling statelessness or “small government” with American conceptions of individual liberty.

Writing for Cato Unbound, Mark Weiner, author of The Rule of the Clan [2], recently made several correct observations about the problem of reconciling statelessness or “small government” with American conceptions of individual liberty.

Many of my readers tend toward libertarianism, and I favor libertarian ideas by default. As a natural-born American, it’s in my DNA. You know what I’m talking about. [3]

However, I also think it’s important to look at how the State makes this swaggering self-conception of the romantic one-against-all rugged individualist possible, and how this modern anti-clannishness actually makes the individual more dependent on the modern State.

To begin, let’s look at Weiner’s essay, and go over what he got right.

What Weiner calls “rule of the clan” is similar to the male group mentality I identified in The Way of Men [4] as “the way of the gang.” Weiner admits that the “rule of the clan” is a natural, universal form of human organization which exerts a “gravitational pull,” and that it is the object of modern liberal government to resist that pull. He defines the “rule of the clan” first as a society based on kinship, but notes that extra-genetic kinship is possible, and points to the existence of gangs and criminal brotherhoods which inevitably form in the smooth, derelict spaces [5] of failed or impotent State influence.

Weiner is also sharp for making the distinction between the modern, liberal idea of honor, which is a self-imposed standard of moral goodness, and the clannish or traditional idea of honor, where individual honor is linked to both the reputation of the group as a whole and the individual’s reputation within the group. He reduces and degrades this primal, tribal form of honor with a vulgar financial analogy, but recognizes that group honor enables group autonomy and group independence. He also recognizes the profound benefits offered by group identification. In his words, the way of the clan “fosters a powerful sense of group solidarity,” “gives persons the dignity and unshakable identity that comes from clan membership,” and “generates a powerful drive toward social justice — a political economy that prizes equality.”

Weiner’s admission of the benefits of clannishness is significant, because he sums up many far-right and reactionary criticisms of modern liberalism and globalism. The prices of liberal, globalist modernity include rootlessness, detachment, an emptiness and desperation for identity that is easily exploited by commercial interests, a lack of community, and a lack of intra-national loyalty that encourages financial greed and insulates elites from the social responsibilities of nobility and the social penalties for betraying their kin, neighbors and countrymen. As the modern, liberal State is easily influenced by large amounts of money, it also insulates the wealthiest individuals from taking physical responsibility for their crimes and betrayals.

Can there be any doubt that it is only the armed protection of the State that has made it possible for the gun-grabbing billionaire Michael Bloomberg to escape a spectacular skyscraper defenestration?

Weiner argues that the modern libertarian idea of individualism, “the modern self” — which generally includes a freedom from responsibility to clan beyond the immediate nuclear family and voluntary instead of mandatory association with groups — is a in fact a product of state development which owes its fragile sense of individual autonomy to the legal protections provided by the state and the conditions of modern life.

This makes perfect sense to me, because I’ve never understood the weird, crypto-religious libertarian obsession with the idea of “natural rights.” I have always understood “rights” as a bargain between rulers and subjects, or in the case of the American democratic ideal, between “the people” and “their” government. In nature, men have no rights. There are no police to call and there is no mechanism to sue any entity that has wronged you or “infringed upon your natural rights.” This is why the primal form of human organization is not the pioneer nuclear family of libertarian individualist fantasy, but the patriarchal clan or tribe or gang of men who unite to provide coordinated protection against danger, and a communal mechanism for righting wrongs or resolving disputes. How “fair” or “just” these tribal systems of resolution and retribution actually are is varied, culturally relative, and subject to taste.

Weiner has concluded that, for the liberal state to thrive and continue to deliver on its promise of individual freedom and autonomy, it must do a better job of doing the things the clan has always done better. He suggests that the state “pursue policies that moderate economic inequality,” “provide space for the flourishing of voluntary civil society organizations that provide opportunities for solidarity,” and “ensure that individuals have fair opportunities to exercise their autonomy within the marketplace,” whatever that means.

Weiner has concluded that, for the liberal state to thrive and continue to deliver on its promise of individual freedom and autonomy, it must do a better job of doing the things the clan has always done better. He suggests that the state “pursue policies that moderate economic inequality,” “provide space for the flourishing of voluntary civil society organizations that provide opportunities for solidarity,” and “ensure that individuals have fair opportunities to exercise their autonomy within the marketplace,” whatever that means.

At first glance, his suggestions sound OK, if you’re into that whole “saving the modern liberal state” thing.

However, after a closer look, they quickly become unworkable. He is also overindulgent of the fictions of the modern State, and he barely mentions the biggest elephants in the room.

When the State pursues policies that moderate economic inequality, to do so, it must become more nationalistic — more clannish, even — not more economically libertarian. A chief contributor to economic inequality in America is surely the ability of corporations, wealthy individuals, even small businesses to undercut American labor and outsource it to foreigners. A little more economic protectionism and certain degree of nationalistic isolationism might go a long way in the long term, but would be damaging to “the economy” in the short term. American politicians are necessarily short-term planners, because they are held accountable in the short-term, so the likelihood of American politicians acting to serve the long term good of the nation while cutting off a foreign supply of cheap labor for corporations, wealthy individuals and small business owners in the short term is approximately zero. This is probably why, for all of their populist posturing about getting tough on immigration, and despite widespread popular support for immigration control, conservative politicians almost always fold.

When Weiner says he wants the State to “provide space for the flourishing of voluntary civil society organizations that provide opportunities for solidarity,” that sounds good, but the reality is that the State as it currently exists would end up micromanaging these organizations to the point where no one would actually want to be members of them anyway. The alternative would be the State creating space for organizations which, if left to flourish organically in harmony with human nature, would eventually challenge the authority of the State itself. Surely, no explicitly kin-oriented groups could be encouraged, especially for white people, because that would be racist. No groups that exclude women could be allowed, because that would be sexist. And the more the State intervenes to regulate and sanction the activities of individuals who associate voluntarily, the more laughable this whole idea of individual autonomy within the context of the State becomes.

What Weiner really fails to acknowledge with this suggestion, even though it is implicit in everything he has written, is that opportunities for “solidarity” and truly meaningful group bonding are a threat to the State, which exactly why there isn’t more room for them now.

People already express group solidarity in ways that are acceptable to the state and its corporate sponsors. They become sports fans. They invest money and time and emotional energy in a group identity that revolves around the dramatic but completely inconsequential activities of, usually, a gang of men.

If men put the same amount of time or energy into forming a highly visible organization with ethnic concerns, for example, half of their enthusiastic new members would probably be FBI agents, because that kind of loyalty would threaten the interests of the liberal state by creating an alternative — and clannish — network of support. The power of the liberal state depends on dependency, and as Weiner has noted, even libertarianism depends on it to protect “rights” and “liberties.”

Finally, in his ode to the State, Weiner perpetuates the fiction that the American State is some kind of benevolent expression of the will of its citizen voters, and he all but ignores the most powerful actors in American politics: corporations. Corporations amass enough money to fund, manufacture and distribute the scientific miracles we use on an everyday basis, but they also perpetuate their own amoral existences by using that money to buy and exert influence on the American political system, whether they are American or foreign-based corporations. Because corporations can exert so much more influence on politics than any voter, the modern liberal state has become a tool of corporate interests, not as Weiner idealizes, a guarantor of individual liberty.

The clan, gang or tribe poses an economic threat to corporations by creating alternative support systems, reduced consumption of goods produced extra-tribally, and the possibility of supply-chain disrupting inter-tribal violence or violence against the State. The State will always oppose clannishness because the state responds first to the interests of self-perpetuating legal entities known as corporations, and because the State is, itself, a self-perpetuating legal entity that will, like any fundamentally amoral corporation, act to perpetuate its own survival above all other concerns.

If the State is over-reaching and becoming the biggest threat to the liberties it supposedly protects, as many men with libertarian tendencies now believe, the solution is not a return to the atomized, go-it-alone individualism that ultimately relies on the liberal State. The only viable option is to increase clannishness or tribalism, which Weiner correctly identified as the natural counter to the modern liberal State.

Source: http://www.jack-donovan.com/axis/2014/03/the-clan-vs-modern-state-dependent-individualism/ [6]

Article printed from Counter-Currents Publishing: http://www.counter-currents.com

URL to article: http://www.counter-currents.com/2014/03/the-clan-vs-modern-state-dependent-individualism/

URLs in this post:

[1] Image: http://www.counter-currents.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/03/pioneers.jpg

[2] The Rule of the Clan: http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/125004362X/ref=as_li_ss_tl?ie=UTF8&camp=1789&creative=390957&creativeASIN=125004362X&linkCode=as2&tag=jackdono-20

[3] You know what I’m talking about.: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=SU0WOZ0jtD4

[4] The Way of Men: http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/0985452307/ref=as_li_ss_tl?ie=UTF8&camp=1789&creative=390957&creativeASIN=0985452307&linkCode=as2&tag=jackdono-20

[5] smooth, derelict spaces: http://www.counter-currents.com/2013/04/deleuze-guattari-and-the-new-right-part-3-capitalism-and-schizophrenia/

[6] http://www.jack-donovan.com/axis/2014/03/the-clan-vs-modern-state-dependent-individualism/: http://www.jack-donovan.com/axis/2014/03/the-clan-vs-modern-state-dependent-individualism/

00:05 Publié dans Traditions | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : clan, clans, traditions, théorie politique, politologie, sciences politiques |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 14 mars 2014

Spartan Women

Spartan Women

Ex: http://aristocratsofthesoul.wordpress.com

Sarah B. Pomeroy

Sarah B. Pomeroy

Spartan Women

Oxford University Press, 2002

Ancient Sparta is known not only for its great warriors, but also for its unusual treatment of women. Further north in democratic Athens, modest women were rarely educated and mostly kept sequestered indoors. But in the militarist state of Sparta, the government insisted that both boys and girls be given an education from childhood. Boys were trained to be future warriors, and women to be the mother of warriors — a task that required a variety of skills.

Sarah B. Pomeroy, a professor at New York’s Hunter College and the Graduate Center at the City University, delves into the unique education and lifestyles of women in Sparta in Spartan Women. Although its primary focus is women, the reader will learn much in the book about the men in this city-state in the south-eastern Peloponnese, as well as about the lives of both men and women in classical Athens.

Women’s Education in Sparta

Compared to other Greek women, Spartans had vastly more free time to do what they wanted. One reason for this was because Sparta was highly dependent on the labor of slaves (called helots), and Spartan citizens were not allowed to engage in most forms of manual labor. This meant that even the women were free from much domestic drudgery. The men of Sparta were full-time warriors, and consequently, Spartan women were usually more cultured than the men. For example, girls were trained in singing, dancing, and playing instruments, and singing competitions often were held between individuals and rival choruses.

Pomeroy says that there is much reason to believe that literacy was common among women in Sparta. There are numerous references to women writing letters to their sons at war (usually these consisted of urging their sons to be brave warriors). And Spartan women also were encouraged in public speaking. In Protagoras, Plato even refers to the women of Sparta and Crete, who take pride in their educations and are skilled in philosophical debate. Common themes for women’s speeches included praising the brave and reviling cowards and bachelors. Another testimony to Spartan women’s education: The Neoplatonist philosopher Iamblichus said there were 17 or 18 women among Pythagoras’ 235 disciples; about one-third of the women were Spartans, while less than 1 percent were Spartan men.

Women could own land in Sparta, and by Aristotle’s time, they owned two-fifths of the land in Laconia. Another privilege of Spartan women, according to Pomeroy: “of all Greek women, Spartans alone drank wine not only at festivals, but also as part of their daily fare.” Although they could not vote, they participated in political campaigns and were said to have much influence over their husbands (according to Aristotle).

Spartan Women and Sports

Spartan Women also details women’s role in sports, another area where they were able to receive training and to excel. Their training was similar to that of boys, but less intense. Women participated in trials of strength, racing competitions, wrestling, discus throwing, and hurling the javelin. Some athletic competitions were held in honor of female deities.

The encouragement of athleticism in women appears to be based on women’s role as mothers. According to Xenophon, Lycurgus (who created Sparta’s constitution) thought that having two physically healthy parents would be more likely to produce healthy offspring.

Young men and women often exercised in the nude, and there was even a “Festival of Nude Youths.” Confirmed bachelors, according to Plutarch, were banned from attending. For the others, it was a chance to view potential marriage partners.

Marriage in Sparta