Le pivot de Moscou vers l’Asie pour construire la Grande Eurasie a un air d’inévitabilité historique qui met les États-Unis et l’UE à l’épreuve.

Les futurs historiens pourraient l’enregistrer comme le jour où le ministre russe des Affaires étrangères Sergueï Lavrov, habituellement imperturbable, a décidé qu’il en avait assez :

« Nous nous habituons au fait que l’Union Européenne tente d’imposer des restrictions unilatérales, des restrictions illégitimes et nous partons du principe, à ce stade, que l’Union Européenne est un partenaire peu fiable ».

Josep Borrell, le chef de la politique étrangère de l’Union européenne, en visite officielle à Moscou, a dû faire face aux conséquences.

Lavrov, toujours parfait gentleman, a ajouté : « J’espère que l’examen stratégique qui aura lieu bientôt se concentrera sur les intérêts clés de l’Union Européenne et que ces entretiens contribueront à rendre nos contacts plus constructifs ».

Il faisait référence au sommet des chefs d’État et de gouvernement de l’UE qui se tiendra le mois prochain au Conseil européen, où ils discuteront de la Russie. Lavrov ne se fait pas d’illusions : les « partenaires peu fiables » se comporteront en adultes.

Pourtant, on peut trouver quelque chose d’immensément intrigant dans les remarques préliminaires de Lavrov lors de sa rencontre avec Borrell : « Le principal problème auquel nous sommes tous confrontés est le manque de normalité dans les relations entre la Russie et l’Union Européenne – les deux plus grands acteurs de l’espace eurasiatique. C’est une situation malsaine, qui ne profite à personne ».

Les deux plus grands acteurs de l’espace eurasiatique (mes italiques). Que cela soit clair. Nous y reviendrons dans un instant.

Dans l’état actuel des choses, l’UE semble irrémédiablement accrochée à l’aggravation de la « situation malsaine ». La chef de la Commission européenne, Ursula von der Leyen, a fait échouer le programme de vaccination de Bruxelles. Elle a envoyé Borrell à Moscou pour demander aux entreprises européennes des droits de licence pour la production du vaccin Spoutnik V – qui sera bientôt approuvé par l’UE.

Et pourtant, les eurocrates préfèrent se plonger dans l’hystérie, en faisant la promotion des bouffonneries de l’agent de l’OTAN et fraudeur condamné Navalny – le Guaido russe.

Pendant ce temps, de l’autre côté de l’Atlantique, sous le couvert de la « dissuasion stratégique », le chef du STRATCOM américain, l’amiral Charles Richard, a laissé échapper avec désinvolture qu’il « existe une réelle possibilité qu’une crise régionale avec la Russie ou la Chine puisse rapidement dégénérer en un conflit impliquant des armes nucléaires, si elles percevaient qu’une perte conventionnelle menaçait le régime ou l’État ».

Ainsi, la responsabilité de la prochaine – et dernière – guerre est déjà attribuée au comportement « déstabilisateur » de la Russie et de la Chine. On suppose qu’elles vont « perdre » – et ensuite, dans un accès de rage, passer au nucléaire. Le Pentagone ne sera qu’une victime ; après tout, affirme STRATCOM, nous ne sommes pas « enlisés dans la Guerre froide ».

Les planificateurs du STRATCOM devraient lire le crack de l’analyse militaire Andrei Martyanov, qui depuis des années est en première ligne pour expliquer en détail comment le nouveau paradigme hypersonique – et non les armes nucléaires – a changé la nature de la guerre.

Après une discussion technique détaillée, Martyanov montre comment « les États-Unis n’ont tout simplement pas de bonnes options actuellement. Aucune. La moins mauvaise option, cependant, est de parler aux Russes et non en termes de balivernes géopolitiques et de rêves humides selon lesquels les États-Unis peuvent, d’une manière ou d’une autre, convaincre la Russie « d’abandonner » la Chine – les États-Unis n’ont rien, zéro, à offrir à la Russie pour le faire. Mais au moins, les Russes et les Américains peuvent enfin régler pacifiquement cette supercherie « d’hégémonie » entre eux, puis convaincre la Chine de s’asseoir à la table des trois grands et de décider enfin comment gérer le monde. C’est la seule chance pour les États-Unis de rester pertinents dans le nouveau monde ».

L’empreinte de la Horde d’Or

Bien que les chances soient négligeables pour que l’Union européenne se ressaisisse sur la « situation malsaine » avec la Russie, rien n’indique que ce que Martyanov a décrit sera pris en compte par l’État profond américain.

La voie à suivre semble inéluctable : sanctions perpétuelles ; expansion perpétuelle de l’OTAN le long des frontières russes ; constitution d’un cercle d’États hostiles autour de la Russie ; ingérence perpétuelle des États-Unis dans les affaires intérieures russes – avec une armée de la cinquième colonne ; la guerre de l’information perpétuelle et à grande échelle.

Lavrov affirme de plus en plus clairement que Moscou n’attend plus rien. Les faits sur le terrain, cependant, continueront de s’accumuler.

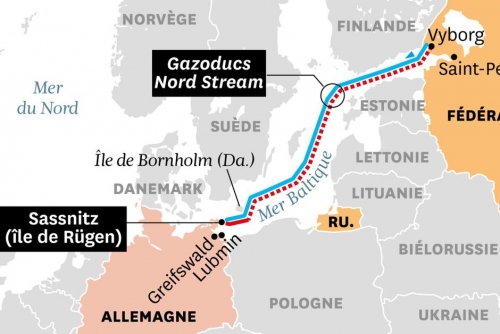

Nord Stream 2 sera terminé – sanctions ou pas – et fournira le gaz naturel dont l’Allemagne et l’UE ont tant besoin. Le fraudeur Navalny, qui a été condamné – 1% de « popularité » réelle en Russie – restera en prison. Les citoyens de toute l’UE recevront Spoutnik V. Le partenariat stratégique entre la Russie et la Chine continuera de se renforcer.

Pour comprendre comment nous en sommes arrivés à ce gâchis russophobe malsain, une feuille de route essentielle est fournie par le Conservatisme russe, une nouvelle étude passionnante de philosophie politique réalisée par Glenn Diesen, professeur associé à l’Université de la Norvège du Sud-Est, chargé de cours à l’École supérieure d’Économie de Moscou, et l’un de mes éminents interlocuteurs à Moscou.

Diesen commence en se concentrant sur l’essentiel : la géographie, la topographie et l’histoire. La Russie est une vaste puissance terrestre sans accès suffisant aux mers. La géographie, affirme-t-il, conditionne les fondements des « politiques conservatrices définies par l’autocratie, un concept ambigu et complexe de nationalisme, et le rôle durable de l’Église orthodoxe » – impliquant une résistance au « laïcisme radical ».

Il est toujours crucial de se rappeler que la Russie n’a pas de frontières naturelles défendables ; elle a été envahie ou occupée par les Suédois, les Polonais, les Lituaniens, la Horde d’Or mongole, les Tatars de Crimée et Napoléon. Sans parler de l’invasion nazie, qui a été extrêmement sanglante.

Qu’y a-t-il dans l’étymologie d’un mot ? Tout : « sécurité », en russe, c’est byezopasnost. Il se trouve que c’est une négation, car byez signifie « sans » et opasnost signifie « danger ».

La composition historique complexe et unique de la Russie a toujours posé de sérieux problèmes. Oui, il y avait une étroite affinité avec l’Empire byzantin. Mais si la Russie « revendiquait le transfert de l’autorité impériale de Constantinople, elle serait forcée de la conquérir ». Et revendiquer le rôle, l’héritage et d’être le successeur de la Horde d’Or reléguerait la Russie au seul statut de puissance asiatique.

Sur la voie de la modernisation de la Russie, l’invasion mongole a non seulement provoqué un schisme géographique, mais a laissé son empreinte sur la politique : « L’autocratie est devenue une nécessité suite à l’héritage mongol et à l’établissement de la Russie comme un empire eurasiatique avec une vaste étendue géographique mal connectée ».

« Un Est-Ouest colossal »

La Russie, c’est la rencontre de l’Est et de l’Ouest. Diesen nous rappelle comment Nikolai Berdyaev, l’un des plus grands conservateurs du XXe siècle, l’avait déjà bien compris en 1947 : « L’incohérence et la complexité de l’âme russe peuvent être dues au fait qu’en Russie, deux courants de l’histoire du monde – l’Est et l’Ouest – se bousculent et s’influencent mutuellement (…) La Russie est une section complète du monde – un Est-Ouest colossal ».

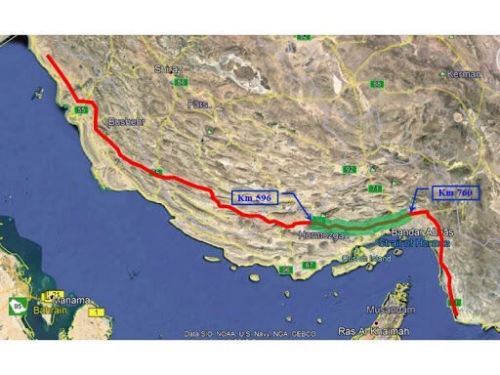

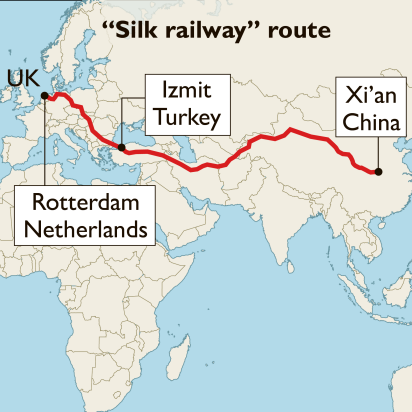

Le Transsibérien, construit pour renforcer la cohésion interne de l’empire russe et pour projeter la puissance en Asie, a changé la donne : « Avec l’expansion des colonies agricoles russes à l’est, la Russie remplace de plus en plus les anciennes routes qui contrôlaient et reliaient auparavant l’Eurasie ».

Il est fascinant de voir comment le développement de l’économie russe a abouti à la théorie du « Heartland » de Mackinder – selon laquelle le contrôle du monde nécessitait le contrôle du supercontinent eurasiatique. Ce qui a terrifié Mackinder, c’est que les chemins de fer russes reliant l’Eurasie allaient saper toute la structure de pouvoir de la Grande-Bretagne en tant qu’empire maritime.

Diesen montre également comment l’Eurasianisme – apparu dans les années 1920 parmi les émigrés en réponse à 1917 – était en fait une évolution du conservatisme russe.

L’Eurasianisme, pour un certain nombre de raisons, n’est jamais devenu un mouvement politique unifié. Le cœur de l’Eurasianisme est l’idée que la Russie n’était pas un simple État d’Europe de l’Est. Après l’invasion des Mongols au XIIIe siècle et la conquête des royaumes tatars au XVIe siècle, l’histoire et la géographie de la Russie ne pouvaient pas être uniquement européennes. L’avenir exigerait une approche plus équilibrée – et un engagement avec l’Asie.

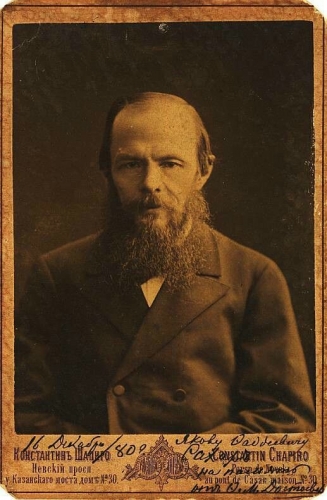

Dostoïevski l’avait brillamment formulé avant tout le monde, en 1881 :

« Les Russes sont autant asiatiques qu’européens. L’erreur de notre politique au cours des deux derniers siècles a été de faire croire aux citoyens européens que nous sommes de vrais Européens. Nous avons trop bien servi l’Europe, nous avons pris une trop grande part à ses querelles intestines (…) Nous nous sommes inclinés comme des esclaves devant les Européens et n’avons fait que gagner leur haine et leur mépris. Il est temps de se détourner de l’Europe ingrate. Notre avenir est en Asie ».

Lev Gumilev était sans aucun doute la superstar d’une nouvelle génération d’Eurasianistes. Il affirmait que la Russie avait été fondée sur une coalition naturelle entre les Slaves, les Mongols et les Turcs. « The Ancient Rus and the Great Steppe », publié en 1989, a eu un impact immense en Russie après la chute de l’URSS – comme je l’ai appris de mes hôtes russes lorsque je suis arrivé à Moscou via le Transsibérien à l’hiver 1992.

Comme l’explique Diesen, Gumilev proposait une sorte de troisième voie, au-delà du nationalisme européen et de l’internationalisme utopique. Une Université Lev Gumilev a été créée au Kazakhstan. Poutine a qualifié Gumilev de « grand Eurasien de notre temps ».

Diesen nous rappelle que même George Kennan, en 1994, a reconnu la lutte des conservateurs pour « ce pays tragiquement blessé et spirituellement diminué ». Poutine, en 2005, a été beaucoup plus clair. Il a souligné :

« L’effondrement de l’Union soviétique a été la plus grande catastrophe géopolitique du siècle. Et pour le peuple russe, ce fut un véritable drame (…) Les anciens idéaux ont été détruits. De nombreuses institutions ont été démantelées ou simplement réformées à la hâte. (…) Avec un contrôle illimité sur les flux d’information, les groupes d’oligarques ont servi exclusivement leurs propres intérêts commerciaux. La pauvreté de masse a commencé à être acceptée comme la norme. Tout cela a évolué dans un contexte de récession économique des plus sévères, de finances instables et de paralysie dans la sphère sociale ».

Appliquer la « démocratie souveraine »

Nous arrivons ainsi à la question cruciale de l’Europe.

Dans les années 1990, sous la houlette des atlantistes, la politique étrangère russe était axée sur la Grande Europe, un concept basé sur la Maison européenne commune de Gorbatchev.

Et pourtant, dans la pratique, l’Europe de l’après-Guerre froide a fini par se configurer comme l’expansion ininterrompue de l’OTAN et la naissance – et l’élargissement – de l’UE. Toutes sortes de contorsions libérales ont été déployées pour inclure toute l’Europe tout en excluant la Russie.

Diesen a le mérite de résumer l’ensemble du processus en une seule phrase : « La nouvelle Europe libérale représentait une continuité anglo-américaine en termes de règle des puissances maritimes, et l’objectif de Mackinder d’organiser la relation germano-russe selon un format à somme nulle pour empêcher l’alignement des intérêts ».

Pas étonnant que Poutine, par la suite, ait dû être érigé en épouvantail suprême, ou « en nouvel Hitler ». Poutine a catégoriquement rejeté le rôle pour la Russie de simple apprentie de la civilisation occidentale – et son corollaire, l’hégémonie (néo)libérale.

Il restait néanmoins très accommodant. En 2005, Poutine a souligné que « par-dessus tout, la Russie était, est et sera, bien sûr, une grande puissance européenne ». Ce qu’il voulait, c’était découpler le libéralisme de la politique de puissance – en rejetant les principes fondamentaux de l’hégémonie libérale.

Poutine disait qu’il n’y a pas de modèle démocratique unique. Cela a finalement été conceptualisé comme une « démocratie souveraine ». La démocratie ne peut pas exister sans souveraineté ; cela implique donc d’écarter la « supervision » de l’Occident pour la faire fonctionner.

Poutine disait qu’il n’y a pas de modèle démocratique unique. Cela a finalement été conceptualisé comme une « démocratie souveraine ». La démocratie ne peut pas exister sans souveraineté ; cela implique donc d’écarter la « supervision » de l’Occident pour la faire fonctionner.

Diesen fait remarquer que si l’URSS était un « Eurasianisme radical de gauche, certaines de ses caractéristiques eurasiatiques pourraient être transférées à un Eurasianisme conservateur ». Diesen note comment Sergey Karaganov, parfois appelé le « Kissinger russe », a montré « que l’Union soviétique était au centre de la décolonisation et qu’elle a été l’artisan de l’essor de l’Asie en privant l’Occident de la capacité d’imposer sa volonté au monde par la force militaire, ce que l’Occident a fait du XVIe siècle jusqu’aux années 1940 ».

Ce fait est largement reconnu dans de vastes régions du Sud global – de l’Amérique latine et de l’Afrique à l’Asie du Sud-Est.

La péninsule occidentale de l’Eurasie

Ainsi, après la fin de la Guerre froide et l’échec de la Grande Europe, le pivot de Moscou vers l’Asie pour construire la Grande Eurasie ne pouvait qu’avoir un air d’inévitabilité historique.

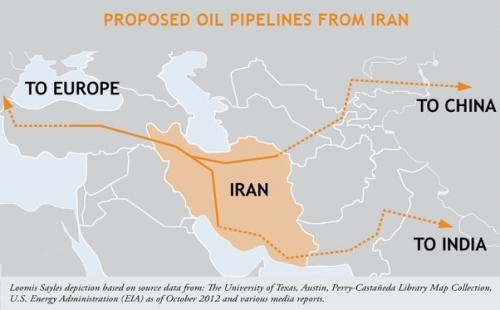

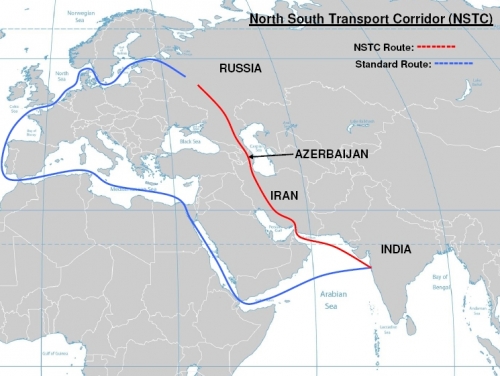

La logique est implacable. Les deux pôles géoéconomiques de l’Eurasie sont l’Europe et l’Asie de l’Est. Moscou veut les relier économiquement en un supercontinent : c’est là que la Grande Eurasie rejoint l’Initiative Ceinture et Route chinoise (BRI). Mais il y a aussi la dimension russe supplémentaire, comme le note Diesen : la « transition de la périphérie habituelle de ces centres de pouvoir vers le centre d’une nouvelle construction régionale ».

D’un point de vue conservateur, souligne Diesen, « l’économie politique de la Grande Eurasie permet à la Russie de surmonter son obsession historique pour l’Occident et d’établir une voie russe organique vers la modernisation ».

Cela implique le développement d’industries stratégiques, de corridors de connectivité, d’instruments financiers, de projets d’infrastructure pour relier la Russie européenne à la Sibérie et à la Russie du Pacifique. Tout cela sous un nouveau concept : une économie politique industrialisée et conservatrice.

Le partenariat stratégique Russie-Chine est actif dans ces trois secteurs géoéconomiques : industries stratégiques/plates-formes technologiques, corridors de connectivité et instruments financiers.

Cela propulse la discussion, une fois de plus, vers l’impératif catégorique suprême : la confrontation entre le Heartland et une puissance maritime.

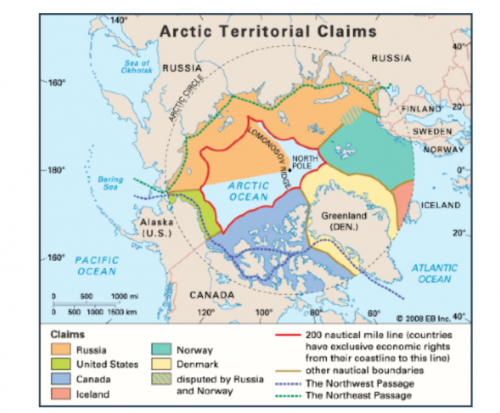

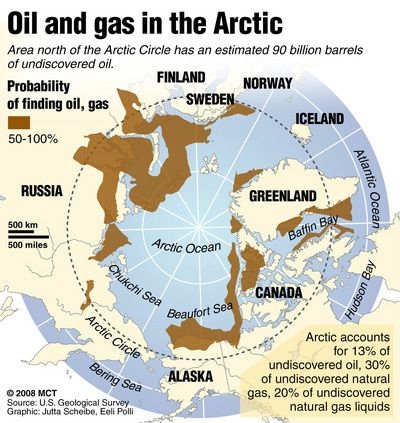

Les trois grandes puissances eurasiatiques, historiquement, étaient les Scythes, les Huns et les Mongols. La raison principale de leur fragmentation et de leur décadence est qu’ils n’ont pas pu atteindre – et contrôler – les frontières maritimes de l’Eurasie.

La quatrième grande puissance eurasiatique était l’empire russe – et son successeur, l’URSS. L’URSS s’est effondrée parce que, encore une fois, elle n’a pas pu atteindre – et contrôler – les frontières maritimes de l’Eurasie.

Les États-Unis l’en ont empêchée en appliquant une combinaison de Mackinder, Mahan et Spykman. La stratégie américaine est même devenue connue sous le nom de mécanisme de confinement Spykman-Kennan – tous ces « déploiements avancés » dans la périphérie maritime de l’Eurasie, en Europe occidentale, en Asie de l’Est et au Moyen-Orient.

Nous savons tous à présent que la stratégie globale des États-Unis en mer – ainsi que la raison principale pour laquelle les États-Unis sont entrés dans la Première et la Seconde Guerre mondiale – était de prévenir l’émergence d’un hégémon eurasiatique par tous les moyens nécessaires.

Quant à l’hégémonie américaine, elle a été conceptualisée de façon grossière – avec l’arrogance impériale requise – par le Dr Zbig « Grand Échiquier » Brzezinski en 1997 : « Pour empêcher la collusion et maintenir la dépendance sécuritaire entre les vassaux, pour garder les affluents souples et protégés, et pour empêcher les barbares de se rassembler ». Le bon vieux « Diviser pour mieux régner », appliqué par le biais de la « domination du système ».

C’est ce système qui est en train de s’effondrer – au grand désespoir des suspects habituels. Diesen (photo) note comment, « dans le passé, pousser la Russie en Asie reléguait la Russie dans l’obscurité économique et éliminait son statut de puissance européenne ». Mais maintenant, avec le déplacement du centre de gravité géoéconomique vers la Chine et l’Asie de l’Est, c’est un tout nouveau jeu.

La diabolisation permanente de la Russie-Chine par les États-Unis, associée à la mentalité de « situation malsaine » des sbires de l’UE, ne fait que rapprocher la Russie de la Chine, au moment même où la domination mondiale de l’Occident, qui dure depuis deux siècles seulement, comme l’a prouvé Andre Gunder Frank, touche à sa fin.

La diabolisation permanente de la Russie-Chine par les États-Unis, associée à la mentalité de « situation malsaine » des sbires de l’UE, ne fait que rapprocher la Russie de la Chine, au moment même où la domination mondiale de l’Occident, qui dure depuis deux siècles seulement, comme l’a prouvé Andre Gunder Frank, touche à sa fin.

Diesen, peut-être trop diplomatiquement, s’attend à ce que « les relations entre la Russie et l’Occident changent également à terme avec la montée de l’Eurasie. La stratégie hostile de l’Occident à l’égard de la Russie est conditionnée par l’idée que la Russie n’a nulle part où aller et qu’elle doit accepter tout ce que l’Occident lui offre en termes de « partenariat ». La montée de l’Est modifie fondamentalement la relation de Moscou avec l’Occident en permettant à la Russie de diversifier ses partenariats ».

Il se peut que nous approchions rapidement du moment où la Russie de la Grande Eurasie présentera à l’Allemagne une offre à prendre ou à laisser. Soit nous construisons ensemble le Heartland, soit nous le construisons avec la Chine – et vous ne serez qu’un spectateur de l’histoire. Bien sûr, il y a toujours la possibilité d’un axe inter-galaxies Berlin-Moscou-Pékin. Des choses plus surprenantes se sont produites.

En attendant, Diesen est convaincu que « les puissances terrestres eurasiatiques finiront par intégrer l’Europe et d’autres États à la périphérie intérieure de l’Eurasie. Les loyautés politiques se déplaceront progressivement à mesure que les intérêts économiques se tourneront vers l’Est et que l’Europe deviendra progressivement la péninsule occidentale de la Grande Eurasie ».

Voilà qui donne à réfléchir aux colporteurs péninsulaires de la « situation malsaine ».

Traduit par Réseau International

***

«Qui veut la paix prépare la guerre»: la Russie annonce être prête en cas de rupture des relations avec l'UE

La Russie est prête à rompre ses relations diplomatiques avec l’Union européenne si cette dernière adopte des sanctions créant des risques pour les secteurs sensibles de l‘économie, a déclaré ce vendredi le chef de la diplomatie russe, Sergueï Lavrov, sur la chaîne YouTube Soloviev Live.

« Nous y sommes prêts. [Nous le ferons] si nous voyons, comme nous l’avons senti plus d’une fois, que des sanctions sont imposées dans certains secteurs qui créent des risques pour notre économie, y compris dans des sphères sensibles. Nous ne voulons pas nous isoler de la vie internationale mais il faut s’y préparer. Qui veut la paix prépare la guerre ».

De nouvelles sanctions en vue

Cette semaine, le chef de la diplomatie de l’Union européenne Josep Borrell a annoncé, après sa visite à Moscou, la possibilité de nouvelles sanctions. Il s’est dit préoccupé par les « choix géostratégiques des autorités russes ».

Condamnant les autorités pour avoir emprisonné en janvier l’opposant Alexeï Navalny et les qualifiant de « sans pitié », Josep Borrell a notamment indiqué dans son blog que sa visite avait conforté son opinion selon laquelle « l’Europe et la Russie s’éloignaient petit à petit l’une de l’autre ».

Les propos tenus à Moscou

Lors de sa visite dans la capitale russe du 4 au 6 février, Josep Borrell avait vanté le vaccin Spoutnik V, le qualifiant de « bonne nouvelle pour l’humanité ». Il avait en outre espéré que l’Agence européenne pour les médicaments l’enregistrerait.

Il avait également dit qu’il y avait des domaines dans lesquels la Russie et l’UE pouvaient et devaient coopérer, et que Bruxelles était favorable au dialogue avec Moscou, malgré les difficultés.

Anastassia Verbitskaïa - Sputnik

Poutine disait qu’il n’y a pas de modèle démocratique unique. Cela a finalement été conceptualisé comme une « démocratie souveraine ». La démocratie ne peut pas exister sans souveraineté ; cela implique donc d’écarter la « supervision » de l’Occident pour la faire fonctionner.

Poutine disait qu’il n’y a pas de modèle démocratique unique. Cela a finalement été conceptualisé comme une « démocratie souveraine ». La démocratie ne peut pas exister sans souveraineté ; cela implique donc d’écarter la « supervision » de l’Occident pour la faire fonctionner. La diabolisation permanente de la Russie-Chine par les États-Unis, associée à la mentalité de « situation malsaine » des sbires de l’UE, ne fait que rapprocher la Russie de la Chine, au moment même où la domination mondiale de l’Occident, qui dure depuis deux siècles seulement, comme

La diabolisation permanente de la Russie-Chine par les États-Unis, associée à la mentalité de « situation malsaine » des sbires de l’UE, ne fait que rapprocher la Russie de la Chine, au moment même où la domination mondiale de l’Occident, qui dure depuis deux siècles seulement, comme

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Le conservatisme russe était typologiquement très proche du conservatisme d'Europe occidentale, car il possédait les mêmes caractéristiques de base, qui étaient fondées sur l'affirmation de la tradition, la compréhension de l'inégalité et de la hiérarchie comme état naturel de la société, le refus de l'utilisation de méthodes révolutionnaires comme moyen de reconstruction de la société, la lutte contre les idées des "Lumières", la conviction que la société a besoin d'un monopole bien établi sur la discussion et l'interprétation des problèmes sociaux et moraux les plus importants qui doivent être menés par la classe noble et l'Eglise, les classes supérieures étant précisément celles qui sont obligées de soutenir ces principes pour la protection et l'idéalisation de l'Etat.

Le conservatisme russe était typologiquement très proche du conservatisme d'Europe occidentale, car il possédait les mêmes caractéristiques de base, qui étaient fondées sur l'affirmation de la tradition, la compréhension de l'inégalité et de la hiérarchie comme état naturel de la société, le refus de l'utilisation de méthodes révolutionnaires comme moyen de reconstruction de la société, la lutte contre les idées des "Lumières", la conviction que la société a besoin d'un monopole bien établi sur la discussion et l'interprétation des problèmes sociaux et moraux les plus importants qui doivent être menés par la classe noble et l'Eglise, les classes supérieures étant précisément celles qui sont obligées de soutenir ces principes pour la protection et l'idéalisation de l'Etat.![Les_soirées_de_Saint-Pétersbourg___[...]Maistre_Joseph_bpt6k5780037x.JPEG](http://euro-synergies.hautetfort.com/media/00/00/1064431213.JPEG)

Les conservateurs russes ont réussi à mettre partiellement en œuvre un grand nombre des exigences qu'il demandait. C'est ainsi que le 25 mai 1811, un décret est publié "sur les pensions privées", qui stipule que "la noblesse, soutenue par l'État, estime nécessaire de placer sous surveillance les personnes qui viennent de l'étranger en cherchant leurs propres intérêts et en négligeant toutes les affaires intérieures, puisqu'elles n'ont aucune règle pure en matière de moralité ou de connaissance de celle-ci" et "après avoir ruiné la noblesse et les autres classes, ces étrangers préparent lentement la ruine de la société en général car on leur permet d'éduquer les enfants du pays".

Les conservateurs russes ont réussi à mettre partiellement en œuvre un grand nombre des exigences qu'il demandait. C'est ainsi que le 25 mai 1811, un décret est publié "sur les pensions privées", qui stipule que "la noblesse, soutenue par l'État, estime nécessaire de placer sous surveillance les personnes qui viennent de l'étranger en cherchant leurs propres intérêts et en négligeant toutes les affaires intérieures, puisqu'elles n'ont aucune règle pure en matière de moralité ou de connaissance de celle-ci" et "après avoir ruiné la noblesse et les autres classes, ces étrangers préparent lentement la ruine de la société en général car on leur permet d'éduquer les enfants du pays". Finalement, à la suite d'une lutte en coulisses impliquant toutes ces "factions", Speransky finit par tomber en disgrâce en mars 1812, ce qui renforce considérablement les positions du "parti russe" et de Joseph de Maistre. En février 1812, ce dernier se voit proposer d'éditer tous les documents officiels publiés au nom du tsar ; 20 000 roubles lui sont transférés au nom de l'empereur afin d'assurer toutes les dépenses nécessaires "à la préparation et à l'exécution de l'un de ses plans".

Finalement, à la suite d'une lutte en coulisses impliquant toutes ces "factions", Speransky finit par tomber en disgrâce en mars 1812, ce qui renforce considérablement les positions du "parti russe" et de Joseph de Maistre. En février 1812, ce dernier se voit proposer d'éditer tous les documents officiels publiés au nom du tsar ; 20 000 roubles lui sont transférés au nom de l'empereur afin d'assurer toutes les dépenses nécessaires "à la préparation et à l'exécution de l'un de ses plans".

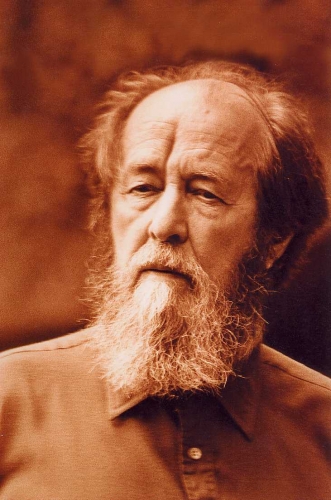

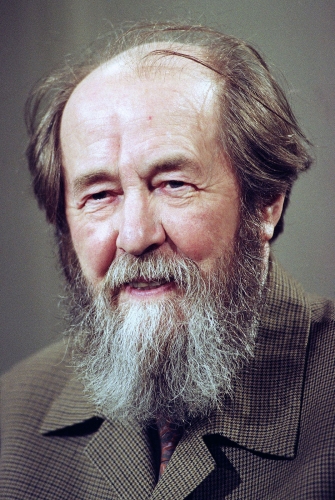

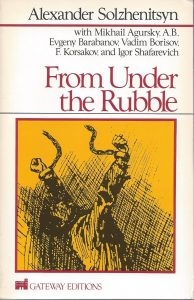

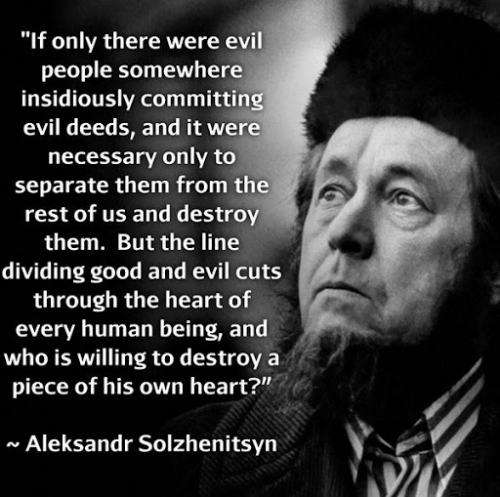

Shortly before being deported from the Soviet Union in 1974, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn contributed three essays to a volume that was later published in the West as From Under the Rubble. The title was a clear metaphor for dissident voices speaking out from beneath the rubble left by communism. The rubble itself represents the remains of the traditional and spiritual life of Solzhenitsyn’s Russia which had been destroyed by the October Revolution and its bloody aftermath. In this volume, Solzhenitsyn lays out what it means to be a nationalist and a dissident against the totalitarian Left. Remarkably little has changed.

Shortly before being deported from the Soviet Union in 1974, Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn contributed three essays to a volume that was later published in the West as From Under the Rubble. The title was a clear metaphor for dissident voices speaking out from beneath the rubble left by communism. The rubble itself represents the remains of the traditional and spiritual life of Solzhenitsyn’s Russia which had been destroyed by the October Revolution and its bloody aftermath. In this volume, Solzhenitsyn lays out what it means to be a nationalist and a dissident against the totalitarian Left. Remarkably little has changed.

Alexandre Douguine se détourne donc d’un certain anti-communisme compassé, car il a compris très tôt les conséquences géopolitiques de la disparition subite de l’URSS et leurs implications psychologiques sur l’homo sovieticus. Cependant, la formation nationale-bolchevique éclatera bientôt en au moins trois factions en raison des divergences croissantes d’ordre politique et personnel entre ces deux principaux animateurs.

Alexandre Douguine se détourne donc d’un certain anti-communisme compassé, car il a compris très tôt les conséquences géopolitiques de la disparition subite de l’URSS et leurs implications psychologiques sur l’homo sovieticus. Cependant, la formation nationale-bolchevique éclatera bientôt en au moins trois factions en raison des divergences croissantes d’ordre politique et personnel entre ces deux principaux animateurs.

Après plusieurs années de santé défaillante, Vladimir Avdeyev est mort du COVID le 5 décembre à Moscou. J'avais rencontré Avdeev lors de la première rencontre dite « du monde blanc » (2006) organisée par le philosophe russe identitaire Pavel Tulaev.Cette initiative fut un jalon dansle combat métapolitique pour la défense de notre identité et de notre civilisation, une première étape dans la collaboration entre divers penseurs de l'identité de l’Europe, de la Russie et de l'Amérique européenne. Nous avons tous deux prononcé nos discours respectifs, tout comme les autres participants, dans un environnement véritablement stimulant sur le plan intellectuel. Après la clôture des conférences de ce premier « Congrès du monde blanc », un concert de musique classique a été organisé dans la Maison de la musique slave en l'honneur des participants par l'Orchestre de l'Académie nationale russe dirigé par le maestro Anatoly Poletaev, qui a dirigé des morceaux de Grieg, Glinka, Tchaïkovski et Rachmaninov. Le lendemain, visite de la galerie Tretiakov où nous avons pu apprécier des chefs-d'œuvre de l'art russe, et enfin visite du musée du peintre Konstantin Vassiliev, une remarquable peinture de l'époque soviétique à thèmes historiques et mythologiques.

Après plusieurs années de santé défaillante, Vladimir Avdeyev est mort du COVID le 5 décembre à Moscou. J'avais rencontré Avdeev lors de la première rencontre dite « du monde blanc » (2006) organisée par le philosophe russe identitaire Pavel Tulaev.Cette initiative fut un jalon dansle combat métapolitique pour la défense de notre identité et de notre civilisation, une première étape dans la collaboration entre divers penseurs de l'identité de l’Europe, de la Russie et de l'Amérique européenne. Nous avons tous deux prononcé nos discours respectifs, tout comme les autres participants, dans un environnement véritablement stimulant sur le plan intellectuel. Après la clôture des conférences de ce premier « Congrès du monde blanc », un concert de musique classique a été organisé dans la Maison de la musique slave en l'honneur des participants par l'Orchestre de l'Académie nationale russe dirigé par le maestro Anatoly Poletaev, qui a dirigé des morceaux de Grieg, Glinka, Tchaïkovski et Rachmaninov. Le lendemain, visite de la galerie Tretiakov où nous avons pu apprécier des chefs-d'œuvre de l'art russe, et enfin visite du musée du peintre Konstantin Vassiliev, une remarquable peinture de l'époque soviétique à thèmes historiques et mythologiques.