QUE PROMET AU MONDE LE DÉMEMBREMENT DE LA RUSSIE ?

Source : https://legrandcontinent.eu/2018/04/12/que-promet-au-mond...

Le GEG Russie est très fier de présenter à ses lecteurs la traduction inédite d’un texte, qui bien que méconnu, reste un fondamental de la pensée politique russe – composition de l’un des penseurs les plus originaux de l’histoire des idées russes, Ivan Iline (1883-1954). Ce texte, intitulé « Que promet au monde le démembrement de la Russie ? » (« Что сулит миру расчленение России ? ») figure, parmi près de 200 articles, dans le recueil « Nos missions » (« Наши задачи », paru à titre posthume à Paris en 1956 et réédité en 1993, non traduit). Iline le rédige en Suisse en 1950, 28 ans après son exil forcé vers l’Europe dans le fameux « bateau des philosophes » qui déporta, sur ordre du Guépéou, la fine fleur de la pensée conservatrice, nationaliste et religieuse russe (qui n’avait pas été exécutée ou emprisonnée), comme Nicolas Berdiaev, Sergueï Boulgakov ou Siméon Frank. Sauvé de l’exécution, il ne reverra jamais son pays, mais put profiter de son exil pour composer une œuvre féconde.

Ivan Iline est un penseur monarchiste et conservateur, farouche opposant à la révolution d’octobre 1917 et idéologue principal de l’Union générale des combattants russes (ROVS), fondée à Paris par le baron Wrangel, un ancien général blanc. Il est aussi un spécialiste de Hegel, auquel il a consacré une thèse intitulée « la philosophie de Hegel, doctrine de la nature concrète de Dieu et de l’homme ». Ses idées mêlent, entre autres, une réfutation de la non-violence tolstoïenne au nom de la guerre contre le mal, et l’apologie d’une “dictature démocratique”, fondée sur “la responsabilité et le service”. Il fut en cela très probablement influencé par Konstantin Leontiev (auteur d’une théorie toute nietzschéenne de la « morale aristocratique »), mais aussi par Vladimir Soloviev.

Tardivement redécouvert en Russie, il rencontre, selon Michel Eltchaninoff, un très vif succès au sein de l’administration poutinienne, dont il serait l’un des principaux idéologues. C’est le réalisateur Nikita Mikhalkov, un proche du pouvoir, qui aurait selon toute vraisemblance introduit ce penseur au Président russe. Ce dernier lui prêterait depuis lors un intérêt certain. Le lecteur le constatera lui-même en lisant ce texte : les thèmes ici abordés déteignent sur la rhétorique de Vladimir Poutine. Il pourra aussi bien s’agir de la méfiance « génétique » de l’Occident vis-à-vis de la Russie, de l’hypocrisie de ses valeurs démocratiques, de l’impossible fédéralisation de la Russie, de la fourberie des dirigeants occidentaux, de la violence au nom du bien, du caractère intrinsèquement majestueux de ce pays, et surtout, de cette obsession pour l’unité de la Grande Russie contre les prédations de ses voisins. D’ailleurs, le Président russe ne s’en cache pas : le philosophe est cité dans plusieurs de ses discours.

Ce texte est très finalement contemporain, pour son virilisme, son antioccidentalisme viscéral, ses accents obsidionaux et son révisionnisme. Il semble, à bien des égards, orienter la politique de Vladimir Poutine. Thèse particulièrement originale à l’ère du « droit à disposer de soi-même » (la Charte des Nations-Unies avait été signée cinq ans auparavant), Iline y dénie par exemple aux « tribus » peuplant la Russie, ainsi qu’aux « petits frères » voisins (ukrainiens, géorgiens ou centrasiatiques) le droit à s’organiser en unités politiques indépendantes. Il ne leur reconnaît en effet aucun génie national, technique, politique ou social, et estime en conséquence qu’ils doivent être incorporés au vaste Empire russe, seul garant de leur conservation. Selon l’auteur, il relèverait de l’intérêt illusoire des occidentaux de « démembrer » la Russie, en incorporant ces « tribus » à leur giron, au nom des principes « dévastateurs » de « démocratie », de « liberté » et de « fédéralisme », transformant ainsi la Russie en de vastes « Balkans », livrée à des guerres incessantes.

Ce texte a pour qualité première sa limpidité. Ce que glissent aujourd’hui les responsables russes derrière le concept flou de « zone d’intérêts privilégiés » ou de « verticale du pouvoir » n’en ressort ainsi qu’avec plus d’éclat. Essentiel à la compréhension des fondements intellectuels de la politique intérieure et étrangère russe, cet article trouve, à l’aune du conflit en Ukraine et de l’hypercentralisation de la Russie, une formidable actualité. Il nous permet aussi, à nous européens, d’inverser notre regard sur notre Grand continent, et finalement, peut-être, de nous saisir de l’un des fragments de l’inconscient collectif de nos voisins russes, ô combien difficiles à comprendre.

Traduit du russe par Nelson Desbenoit, Pierre Bonnet et Théo Lefloch

I

1. Devisant au sujet de la Russie avec un étranger, chaque fidèle patriote russe se doit de lui expliquer que son pays ne correspond pas à une accumulation fortuite de territoires et de peuplades, encore moins à un « mécanisme » de « régions » artificiellement agencées, mais bien à un organisme vivant, historiquement formé et culturellement justifié, ne pouvant faire l’objet d’un démembrement arbitraire. Cet organisme correspond à une unité géographique, dont les différentes parties sont liées par une interdépendance économique ; il constitue une unité spirituelle, linguistique et culturelle, liant historiquement le peuple russe à ses jeunes frères ethniques par une osmose spirituelle ; il forme une unité étatique et stratégique ayant prouvé au monde sa volonté et sa faculté à se défendre ; il incarne enfin l’authentique bastion de la paix universelle et de l’équilibre en Eurasie, et par conséquent de l’ensemble de l’Univers. Son démembrement constituerait une entreprise politique aventureuse, sans précédent historique, et dont l’humanité supporterait durablement les conséquences.

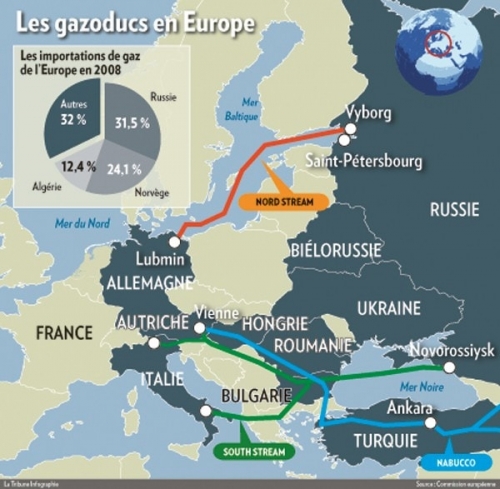

Le démembrement d’un organisme en une multitude de composantes n’a jamais apporté nulle part et n’apportera jamais ni la guérison, ni l’harmonie créative, ni la paix. A contrario, il fut toujours et restera toujours la source d’un douloureux délitement, d’une décomposition progressive, d’un mécontentement, de querelles et d’une contamination généralisée. A notre époque, l’ensemble de l’Univers sera atteint par ce processus. Le territoire russe souffrira d’interminables dissensions et de guerres civiles, dégénérant à l’infini en confrontations à l’échelle mondiale. Cette dégénérescence deviendra absolument irréversible dans la mesure où les puissances du monde entier (européennes comme asiatiques et américaines) placeront leurs richesses, leurs intérêts commerciaux et leurs visées stratégiques au service de l’apparition de nouveaux petits États ; non seulement les voisins impérialistes développeront des rivalités mutuelles, afin d’asseoir leur domination et de s’emparer de « pôles de défense », mais ils s’emploieront également à « annexer » de manière implicite ou explicite ces nouveaux États, instables et vulnérables (l’Allemagne s’étendra vers l’Ukraine et les pays baltes, l’Angleterre s’attaquera au Caucase et à l’Asie centrale, le Japon convoitera les côtes extrême-orientales, etc.). La Russie se transformera en d’immenses « Balkans », source de guerres éternelles, immense terreau de désordres. Elle deviendra un lieu d’errance planétaire, où convergeront les rebuts sociaux et moraux du monde entier (« infiltrés », « occupants », « agitateurs », « espions », spéculateurs révolutionnaires et « missionnaires »). Tous les criminels, intrigants politiques et religieux de l’univers y convergeront en masse. La Russie démembrée deviendra alors l’ulcère incurable de ce monde.

2. Démontrons dès à présent que le démembrement de la Russie, fomenté en secret par les puissants de ce monde, ne possède pas le moindre fondement, ni aucune finalité au plan spirituel ou de la realpolitik, sinon une démagogie révolutionnaire, la crainte absurde d’une Russie unie, et une profonde inimitié vis-à-vis de la monarchie russe et de l’Orthodoxie orientale. Nous savons que les peuples occidentaux ne comprennent ni ne tolèrent la singularité russe. Ils perçoivent l’État russe unifié comme entrave à leur expansion commerciale, linguistique et militaire. Ils s’apprêtent à scier la « branche de bouleau » russe en rameaux, puis à briser ces rameaux séparément pour les brûler dans le brasier déclinant de leur civilisation. Il leur est nécessaire de démembrer la Russie afin de la soumettre au nivellement et à la décomposition occidentaux, la menant ainsi à sa perdition : voici en quoi consiste leur plan haineux et avide de pouvoir.

3. Les peuples occidentaux se réfèreront vainement aux grands principes de « liberté », de « liberté nationale », à l’exigence d’« autonomie politique »… Pourtant, jamais et nulle part les délimitations tribales des peuples n’ont coïncidé avec celles des Etats. L’Histoire dans sa globalité en a apporté les preuves vivantes et convaincantes. Il a toujours existé des tribus et peuples peu nombreux, inaptes à acquérir leur autonomie politique : retracez l’Histoire millénaire des Arméniens, peuple autonome par son caractère et sa culture, cependant dépourvu d’État ; puis demandez-vous où se trouve l’État indépendant des Flamands (4,2 millions d’entre eux vivant en Belgique, un million en Hollande) ? Pourquoi ne sont pas souverains les Gallois et les Ecossais (comptant pour 600 000 habitants) ? Où se trouve l’État des Croates (correspondant à trois millions de personnes), des Slovènes (incluant 1,26 million d’habitants), des Slovaques (près de 2,4 millions), des Vénètes (65 000 personnes) ? Qu’en est-il des Basques français (170 000 habitants), des Basques espagnols (450 000 personnes), des Tsiganes (moins de cinq millions), des Suisses romanches (45 000 personnes), des Catalans d’Espagne (six millions), des Galiciens (2,2 millions de personnes), des Kurdes (plus de deux millions) et de la multitude d’autres tribus asiatiques, africaines, australiennes et américaines ?

Ainsi, les « liens tribaux » en Europe comme sur les autres continents ne correspondent nullement aux frontières étatiques. De nombreuses petites ethnies n’ont trouvé leur salut qu’en s’agrégeant à des peuples de plus grande envergure, constitués en Etats et tolérants : accorder l’indépendance à ces petites peuplades reviendrait soit à les faire passer sous la coupe de nouveaux conquérants, portant ainsi un coup fatal à leur vie culturelle propre, soit à les détruire à jamais, ce qui serait spirituellement dévastateur, économiquement coûteux et politiquement absurde. Souvenons-nous de l’Histoire de l’Empire romain – il s’agissait d’une multitude de peuples « intégrés », bénéficiant des droits liés à la citoyenneté romaine, indépendants et protégés des Barbares. Quid encore de l’Empire britannique contemporain ? Et voici précisément en quoi consiste aussi la mission civilisatrice de la Russie unie.

Ni l’Histoire, ni la culture moderne de la légalité ne connaissent cette loi selon laquelle « à chaque peuplade son État ». Il s’agit là d’une doctrine récente, absurde et mortifère, désormais portée au pinacle dans le but unique de démembrer la Russie unie et de briser sa culture spirituelle propre.

II

4. Que l’on nous ne dise pas, par ailleurs, que les « minorités nationales » de la Russie vivaient sous le joug oppressif d’une majorité russe et de son souverain. C’est une fabulation idiote et fallacieuse. La Russie impériale n’a jamais dénationalisé ses petits peuples, comme l’ont fait, par exemple, les Allemands en Europe occidentale.

Donnez-vous la peine de jeter un coup d’œil à une carte historique de l’Europe à l’époque de Charlemagne et des premiers carolingiens (768-843). Vous y verrez que, presque du Danemark même, le long et au-delà de l’Elbe (du slave « Laba »), à travers Erfurt, jusqu’à Ratisbonne et sur le Danube étaient installées de nombreux peuples slaves : Abodrites, Loutitches, Linones, Heveli, Redari, Oukri, Pomériens, Sorabes et beaucoup d’autres. Où sont-ils tous ? Que reste-t-il d’eux ? Ils ont été conquis, éradiqués et dénationalisés par les Germains. La tactique des conquérants était la suivante : après une victoire militaire, les Germains convoquaient la classe supérieure du peuple conquis. Cette aristocratie était alors massacrée sur place. Puis ce peuple « étêté » était soumis au baptême et converti de force au catholicisme. Les dissidents étaient tués par milliers, les autres étaient germanisés sans vergogne.

A-t-on déjà vu quelque chose de semblable dans l’histoire de la Russie ? Jamais nulle part ! De tous les petits peuples de Russie assimilés par l’Empire au cours de l’histoire, tous ont conservé leur identité propre. Il faut distinguer, c’est vrai, les classes supérieures de ces peuples, mais uniquement parce qu’elles ont été intégrées aux classes supérieures de l’empire. Ni le baptême forcé, ni l’éradication, ni l’uniformisation n’ont été des pratiques russes. La dénationalisation forcée et le nivellement communiste n’ont été introduits que par les bolchéviques.

En voici la preuve : la population allemande, qui avait absorbé tant de peuples, fut soumise à une dénationalisation impitoyable en faveur d’une homogénéité allemande, tandis qu’en Russie, les recensements établirent d’abord plus d’une centaine, puis près de cent soixante tribus linguistiques et jusqu’à trente confessions religieuses différentes. Et messieurs les « démembreurs » voudraient nous faire oublier que la Russie impériale a toujours respecté l’intégrité des compositions tribales lorsqu’il s’agissait de procéder à des démarcations territoriales.

Rappelons l’histoire des colons allemands en Russie. Ont-ils été soumis à quelconque dénationalisation pendant 150 ans ? Entre 40 000 et 50 000 colons se déplacèrent vers la Volga et le sud de la Russie durant la deuxième moitié du XVIIIème siècle (1765-1809). Au début du XXèmesiècle, ils constituaient la couche la plus riche de la paysannerie russe et représentaient 1,2 million d’individus. Leur langue, leurs confessions et leurs coutumes étaient tolérées par tous. Et quand, poussés par les expropriations bolchéviques, ils retournèrent en Allemagne, les Allemands furent étonnés de découvrir qu’ils employaient des dialectes issus du Holstein, du Wurtemberg et d’autres régions. Tout ce qui avait été écrit sur la russification forcée s’écroulait ainsi et fut discrédité.

Mais la propagande politique ne s’arrête pas devant un mensonge aussi évident.

5. Il faut ensuite reconnaître que le démembrement de la Russie constitue un problème territorial insoluble. La Russie impériale n’a jamais considéré ces petits peuples comme du simple « bois de chauffage », susceptibles d’être transférés d’un lieu à vers un autre. Elle ne les a donc jamais arbitrairement déportés d’un bout à l’autre du pays. Leur installation en Russie relevait plutôt d’un processus historique et d’une libre sédimentation. Il s’agissait là d’un processus irrationnel, que l’on ne saurait réduire à des démarcations géographiques précises. Il s’agissait d’un processus de colonisation, de départ, de réinstallation, de dispersion, de confusion, d’assimilation, de reproduction et d’extinction. Ouvrez une carte ethnographique de la Russie prérévolutionnaire (1900-1910) et vous constaterez une extraordinaire diversité : notre pays était parsemé de petits « îlots » nationaux, de « ramifications », « d’environnements », de « baies » tribales, de « détroits », de « canaux » et de « lacs ». Regardez de plus près ce mélange tribal et considérez les avertissements suivants :

a. Toute cette légende sur la carte n’est que symbolique car personne n’a empêché les Géorgiens de vivre à Kiev ou à Saint-Pétersbourg, les Arméniens en Bessarabie ou à Vladivostok, les Lettons à Arkhangelsk ou dans le Caucase, les Circassiens en Estonie, les Grands Russes partout, etc ;

b. C’est pourquoi toutes ces couleurs sur la carte n’indiquent pas l’établissement « exclusif » d’une population tribale, mais une implantation seulement « majoritaire » ;

c. Tous ces peuples, depuis cent ou deux-cents ans, se sont mélangés, et les enfants issus de ces mariages mixtes se sont à leur tour mélangés, encore et toujours.

d. Tenez également compte de la capacité de l’esprit et de la nature russe à intégrer les hommes d’un sang étranger, chose qui se manifeste dans ce proverbe du sud de la Russie : « Papa est turc, maman est grecque, et moi je suis russe » ;

e. Étendez ce processus à l’ensemble du territoire russe – d’Araks au fjord de Varanger et de Saint-Pétersbourg à Iakoutsk – et vous comprendrez pourquoi la tentative bolchévique de diviser la Russie en « républiques » nationales a échoué.

Les bolchéviques n’ont pas réussi à arracher chaque peuple de son territoire propre, parce que tous les peuples de Russie avaient déjà été éparpillés et dispersés, que leur sang avait été mélangé et qu’ils s’étaient géographiquement entremêlés les uns avec les autres.

S’isolant politiquement, chaque peuple prétendait, bien sûr, avoir droit d’usage sur ses propresrivières et ses canaux, sur son sol fertile, ses richesses souterraines, ses pâturages, ses routes commerciales et ses frontières défensives, sans parler de la « matrice » principale de ce peuple, aussi petite fût-elle.

Ainsi, si nous détournons notre attention de ces petits peuples dispersés comme les Votiaks, les Permiaki, les Ziriani, les Vogoules, les Ostiaks, les Tchérémisses, les Mordves, les Tchouvaches (…), et que nous nous concentrons sur les substrats nationaux du Caucase et de l’Asie centrale, nous remarquons une chose. C’est que l’installation des tribus les plus grandes et les plus significatives en Russie est telle que chaque « État » individuel a dû abandonner ses « minorités » à ses voisins, tout en intégrant dans sa propre population des « minorités » étrangères. C’est ce qu’il se passa au début de la Révolution en Asie centrale avec les Ouzbeks, les Tadjiks, les Kirghizes et les Turkmènes. Les tentatives de démarcations nationales n’y ont cependant causé que des rivalités féroces, des haines et des méfiances mutuelles. Ce fut exactement la même chose dans le Caucase. La vieille querelle nationale entre les Azerbaïdjanais tatars et les Arméniens exigeait une division territoriale stricte, mais cette partition s’est révélée complètement inapplicable : des unités territoriales avec une population mixte ont été créées, où seule la présence des troupes soviétiques a empêché des massacres. Des problématiques similaires se sont nouées autour de la démarcation de la Géorgie et de l’Arménie, notamment en raison du fait que les Arméniens de Tiflis, principale ville de Géorgie, représentaient près de la moitié de la population et, qui plus est, la majorité prospère.

Il est entendu que les bolchéviques qui, sous prétexte de favoriser l’« indépendance nationale » voulaient isoler, dénationaliser et internationaliser les peuples russes résolurent tous ces problèmes avec un arbitraire dictatorial, derrière lequel se cachaient des considérations marxistes et la force des armes de l’Armée rouge.

La démarcation nationale-territoriale des peuples était un objectif profondément vain.

III

6. Ajoutons que de nombreuses tribus de Russie ont vécu, jusqu’à nos jours, dans une inculture (малокультурность) spirituelle et politico-étatique complète. Parmi ces tribus, certaines sont demeurées au stade le plus primitif du chamanisme ; toute la « culture » n’y est réduite qu’à un banal artisanat ; le nomadisme y perdure encore ; aucune ne dispose de frontières naturelles pour délimiter son territoire, ni de grande ville, ni de ses propres graphèmes, ni d’écoles primaires et secondaires, ni d’une intelligentsia, ni d’une conscience nationale, ni d’une culture de la légalité. Ils sont encore incapables d’une moindre vie politique, sans même citer l’impossibilité, pour eux, de mener des procédures juridiques complexes, à construire des représentations nationales, à développer des technologies, une diplomatie et des stratégies – cela était su des autorités impériales et fut vérifié par les bolchéviques. Aux mains des bolchéviques, ils obéissent désormais aux moindres gestes de la dictature, à la manière d’une marionnette. A peine les autorités agitent-elles les doigts que l’ensemble de la marionnette s’anime, se courbe, lève docilement les mains et ressasse les vulgarités partisanes et marxistes que lui ont inculqué ses maîtres. La démagogie et la duperie, les expropriations et la terreur, l’anéantissement de la religion et de la vie furent présentés comme l’« épanouissement national » des minorités russes. Et il y eut en Occident des fous et des observateurs véreux qui se félicitèrent de cette « libération des peuples » …

Question inévitable : après la séparation de ces tribus de la Russie, qui les prendra sous sa responsabilité ? Quelle puissance étrangère se jouera d’elles et en retirera la sève vitale ?

Question inévitable : après la séparation de ces tribus de la Russie, qui les prendra sous sa responsabilité ? Quelle puissance étrangère se jouera d’elles et en retirera la sève vitale ?

7. Des décennies d’arbitraire, de famine et de terreur bolchévique se sont écoulées depuis. Même après l’ouragan de la Seconde Guerre mondiale, un « nettoyage national » post-guerre fut entrepris. Depuis maintenant 33 ans, les bolchéviques ont systématiquement éliminé ou affamé les pans les plus récalcitrants de la population et ont déporté les membres de toutes les tribus de Russie dans des camps de concentration, des villes nouvelles et des usines. La Seconde Guerre mondiale a conduit à la déportation de citoyens issus de la moitié européenne de la Russie, menant des « Ukrainiens », des colons Allemands, des Juifs vers l’est, vers l’Oural et au-delà, tandis que d’autres étaient déplacés vers l’ouest, comme les « Ostarbeiter », ou les réfugiés – notamment ceux qui se sont volontairement rendus en Allemagne, à l’instar des Kalmouks. Les Allemands ont occupé des territoires russes comptant près de 85 millions de personnes, massacré des otages et exterminé un demi-million de Juifs. Le rythme des exécutions n’a pas décéléré lorsque les bolchéviques sont parvenus à reprendre les territoires perdus. Pis, les massacres des minorités ont alors commencé : certaines durent être considérées comme presque éteintes – comme les colons Allemands, les Tatars de Crimée, les Karatchaïs, les Tchétchènes ou les Ingouches. Le massacre se poursuit désormais en Estonie, en Lettonie et en Lettonie. Les représentants de l’UNRA estiment aujourd’hui les morts biélorusses à 2,2 millions de personnes, et de sept à neuf millions en Ukraine. De plus, nous savons de source sûre que les populations déclinantes d’Ukraine, de Biélorussie et de la Baltique sont remplacées par des populations issues des provinces centrales, avec d’autres traditions nationales.

Tout cela pour dire que le processus d’extinction et de remplacement national, ainsi que de déplacement de population atteint des proportions sans précédent en Russie depuis la Révolution. Des tribus entières disparurent complètement ou devinrent insignifiantes ; l’ensemble des provinces et des oblasts ont vu, à l’issue de la Révolution, leur population totalement recomposée ; des districts entiers tombèrent en déliquescence. Tous les plans et les estimations des « démembreurs » s’en trouvèrent infondés et caduques. Si la révolution soviétique s’achève en effet par une troisième guerre mondiale, les compositions tribales de la population russe changeront, ce après quoi l’idée même de démembrement politico-national de la Russie deviendra une chimère : un plan non seulement traître, mais aussi grossier et irréalisable.

8. Mais nous devons malgré tout nous préparer aux actions hostiles et saugrenues des « démembreurs » de la Russie, qui tenteront, dans ce chaos post-bolchévique, de la trahir au nom des principes sacro-saints de « liberté », de « démocratie » et de « fédéralisme ». Ils souhaitent mener les peuples et les tribus russes à leur perte. Au nom de la « prospérité », ils veulent livrer la Russie à ses ennemis : opportunistes et politiciens assoiffés de pouvoir. Nous devons nous y préparer, d’abord parce que la propagande allemande a investi beaucoup d’argent et d’efforts dans le séparatisme ukrainien (et peut-être pas uniquement ukrainien) ; ensuite, parce que la psychose de la « démocratie » et du « fédéralisme » influencent largement les penseurs postrévolutionnaires et des carriéristes politiques ; enfin, parce que les partisans du complot contre l’unité de la Russie ne renonceront à leurs ambitions qu’une fois qu’ils auront totalement échoué.

IV

9. Lorsque les bolchéviques s’effondreront , la machine propagandiste internationale s’efforcera de distiller dans le chaos russe ce slogan : « peuples de l’ancienne Russie, désolidarisez-vous ! ». Deux voies pour l’avenir de la Russie émergeront rapidement. Soit d’une part elle verra l’instauration d’une dictature nationale, qui s’arrogera les « rênes du pouvoir » et balaiera ces slogans pernicieux. La dictature mènera la Russie vers son unification, en mettant un terme à tous les mouvements séparatistes du pays. Soit d’autre part, s’il advenait qu’une telle dictature fût caduque, le pays plongera dans un interminable chaos : émigrations, immigrations, revanchisme, pogroms, paralysie des transports, chômage, faim, froid et anarchie (…).

La Russie, sombrant dans l’anarchie, s’abandonnera alors à ses ennemis nationaux, militaires, politiques et religieux. Débutera un cycle interminable de pogroms et de troubles, ce « Maelstrom du mal » que nous avons évoqué en première partie. Certaines tribus partiront ainsi en quête d’un salut illusoire, qu’elles ne trouveront que dans « l’être-en-soi », c’est-à-dire dans leur division.

Il va sans dire que tous nos « bons voisins » voudront profiter de cet état d’anarchie pour justifier leurs interventions au prétexte de leur « défense », d’une « pacification » ou d’un « rétablissement de l’ordre » (…). Ces « bons voisins » useront de leurs modes d’intervention habituels : menace diplomatique, occupation militaire, détournements de matières premières, appropriation de « concessions », pillage de stocks militaires, mise en place d’un parti unique et corruption de masse, constitution de groupes séparatistes (appelées « armées nationales-fédérales »), mise en place de gouvernements fantoches, incitation et aggravation de conflits civils sur le modèle chinois. La nouvelle Ligue des nations tentera quant à elle d’instaurer un « nouvel ordre », en correspondance constante avec Paris, Berlin ou Bruxelles, via des résolutions visant à la suppression et au démembrement de la Russie Nationale.

Admettons que tous ces efforts pour « la démocratie et la liberté » aboutissent et que la Russie soit démembrée. Qu’est-ce que cela apportera aux peuples de Russie et aux puissances voisines ?

10. D’après les estimations les plus modestes, il y existe près de vingt « États » qui ne possèdent ni territoire propre, ni gouvernement efficient, ni lois, ni cours de justice, ni armée, ni population proprement nationale. Près de vingt noms qui ne recouvrent que du vide. Mais la nature a horreur du vide. Et dans ce trou noir, dans ce tourbillon anarchique, sont aspirés des hommes et toute leurs vices. D’abord, tous les nouveaux aventuriers, en mal de nouvelles révolutions ; ensuite, les mercenaires des Etats voisins ; enfin, les opportunistes étrangers, les condottières [1], les spéculateurs et autres « missionnaires » (lisez, pour vous en convaincre, Boris Godounov, d’Alexandre Pouchkine, ou les textes historiques de Shakespeare). Tout ce chaos, toute cette propagande et cette agitation antirusse, toute cette corruption politique et religieuse seront bien entendu entretenus à dessein.

Lentement, de nouveaux Etats seront créés ex nihilo ou selon un processus de fédéralisation. Chacun mènera avec son voisin une lutte à mort pour son intégrité territoriale et pour sa population, ce qui implique, pour la Russie, d’incessantes guerres civiles (…).

Ces nouveaux Etats deviendront, quelques années plus tard, ou bien les satellites de puissances voisines, ou bien des colonies étrangères, ou bien encore des « protectorats ». L’incapacité avérée de la population Russe, à se constituer en une fédération politique, ainsi que leur désir historique « d’indépendance », sont insurmontables. Et lorsque les plan de fédération auront été abandonnés, les peuples russes, dans leur désespoir, préféreront se soumettre aux étrangers plutôt que de se battre pour l’unité panrusse.

11. Afin de prendre la mesure de cette longue démence dont souffrirait la Russie, il suffit d’imaginer le destin d’une « Ukraine autonome ». Cet « État » devrait tout d’abord créer une ligne de défense d’Ovroutch à Koursk, puis à Kharkov, Bakhmout et Marioupol. Un front apparaîtrait ainsi entre l’Ukraine et la Russie. L’Ukraine serait soutenue par l’Allemagne et ses alliés ; et dans l’éventualité d’une nouvelle guerre entre l’Allemagne et la Russie, le front allemand s’étendrait d’emblée de Koursk à Moscou, de Kharkov à la Volga, de Bakhmout et Marioupol au Caucase. Cela représenterait une configuration stratégique inédite, où les Allemands disposeraient d’une avance tactique encore jamais vue.

Il est par ailleurs très aisé de deviner comment la Pologne, la France, l’Angleterre et les Etats-Unis réagiraient à cette nouvelle donne stratégique : il s’empresseraient de reconnaître l’« Ukraine autonome » – ce qui reviendrait, ironiquement, à l’offrir aux Allemands (…).

Peut-être l’Europe occidentale prendrait alors conscience du danger que représente pour elle leur obsession pour le « fédéralisme » et le démembrement de la Russie.

V

12. Compte tenu de ce qui a été dit jusqu’ici, il nous paraît désormais évident que l’intérêt profond des plans de démembrement de la Russie est limité, aussi bien pour la Russie que pour l’ensemble de l’humanité. Certes, tant que l’on se satisfera de verbiages, tant que les théories politiques ne s’appuieront que sur des slogans trompeurs et que l’on ne misera que sur des traîtres à la Russie, tant que les visées impérialistes des voisins se feront discrètes, tant que l’on considérera la Russie comme morte et enterrée, et donc sans défense, son démembrement paraîtra simple et aller de soi. Mais un jour les grandes puissances prendront conscience des répercussions catastrophiques que ce démembrement aura sur eux, car un jour la Russie s’éveillera et leur parlera ; alors toutes les solutions ne deviendront plus que des problèmes, et ce qui paraissait simple jadis deviendra extrêmement complexe.

Bien qu’elle fût l’objet de querelles incessantes, cette Russie en proie aux pillages, personne ne pourra la contrôler. Elle représentera alors un danger aussi immense qu’inacceptable pour l’ensemble de l’humanité. L’économie mondiale, déjà déséquilibrée par la dégradation de la production russe, se verra ainsi frappée de stagnation pour des dizaines d’années.

Le monde, déjà instable, devra relever épreuves sans précédent. Le démembrement de la Russie n’offrira rien aux puissances lointaines, mais renforcera inexorablement les puissances voisines – les impérialistes. Il est difficile d’imaginer une chose plus bénéfique pour l’Allemagne que la proclamation d’une « pseudo-fédération » en Russie : cela reviendrait à « effacer » tous les acquis des deux guerres mondiales, ainsi que de l’entre-deux guerres (1918-1939), et d’offrir à l’Allemagne l’hégémonie mondiale sur un plateau d’argent. L’indépendance de l’Ukraine ne peut être qu’une passerelle vers cette hégémonie allemande (…).

Les ennemis de la Russie démontrent leur frivolité et leur bêtise en voulant introduire les tribus russes au principe – déconcertant – du démembrement. Cette idée fut déjà proposée par les puissances européennes au Congrès de Versailles (1918). Elle fut acceptée et appliquée.

Et puis qu’advint-il ?

En Europe, un certain nombre de petits Etats apparurent, devant assurer, bien que faibles, leur propre défense : l’Estonie, la Lettonie, la Lituanie ; la Pologne, vaste mais inconséquente ; la Tchécoslovaquie, stratégiquement insignifiante, friable et divisée dans ses propres frontières ; l’Autriche, petite et désarmée ; la Hongrie, réduite, affaiblie et dépouillée ; jusqu’à la Roumanie, ridiculement boursouflée [2], mais dénuée de toute valeur stratégique réelle – et tout cela aux portes de l’Allemagne qui, désavouée, rêvait de revanche. Trente ans se sont écoulés depuis, et lorsque nous regardons le cours des évènements, nous sommes forcés de nous demander si les politiciens de Versailles ne cherchaient pas à transformer ces Etats en une proie facile pour l’Allemagne belliqueuse – de Narva à Varna, et de Bregenz à Baranavitchy. Car ce sont bien eux qui, après tout, ont fait de ces régions européennes une sorte de « jardin d’enfants », tout en laissant à ces petits « chaperons rouges » le soin de se défendre eux-mêmes, face au loup affamé et en colère… Étaient-ils naïfs au point de croire qu’une « gouvernante » française pourrait châtrer le loup ? Ou alors ils ont sous-estimé l’énergie vitale et les fières intentions allemandes ? Peut-être encore pensaient-ils que la Russie aurait encore l’intention de rétablir l’équilibre dans la balance européenne, certains que l’Etat soviétique représentait encore la Russie ? Qu’importe la question, elle est absurde…

Il est désormais difficile de savoir ce à quoi pouvaient bien penser ces messieurs, ou plutôt ce à quoi ils n’ont pas pensé. La seule évidence, c’est que le démembrement de l’Europe, désormais partagée par les impérialistes allemands et soviétiques, est le fruit de leur bêtise, probablement la plus grande du vingtième siècle. Malheureusement, cette leçon ne leur a rien appris vis-à-vis du principe de démembrement, projet qui fut exhumé aussitôt achevée la guerre.

Pour nous, le fait que les politiciens européens aient commencé à parler au même moment d’union pan-européenne et de démembrement de la Grande Russie, est très symptomatique ! Nous subissons cette cacophonie depuis déjà longtemps. Dans les années 1920, les éminents socialistes révolutionnaires se gargarisaient en public de leur prouesse : éviter d’employer le nom « Russie » et lui préférer cette locution, pour le moins évocatrice : « les pays situés à l’Est de la ligne Curzon ». Cette terminologie d’apparence prometteuse, en réalité scélérate, nous ne l’avons jamais oubliée, et en en avons tiré les conclusions appropriées : le monde des intrigues souhaite, en coulisses, enterrer la Russie nationale et unie.

Mais cela n’est ni avisé, ni clairvoyant. Tout ceci ne procède que d’une haine et d’une hystérie séculaires. La Russie, ce n’est pas de la poussière humaine, ni un chaos. C’est avant tout une grande nation, qui n’a pas abdiqué sa force, ni renoncé à sa vocation. Ce peuple russe avait faim « d’ordre libre » (« свободный порядок »), de labeur tranquille, de prospérité et de culture nationale. Ne l’enterrez pas prématurément !

Car un jour viendra, où ce peuple s’extirpera de la fosse spirituelle où on l’a jeté, et réclamera ses droits !

[1] Désigne un chef de mercenaires italien qui, au Moyen-Âge, louait ses services de guerre à un prince, à une république, et parfois se saisissait du pouvoir dans une cité conquise ; mais aussi, un homme qui conduit ses entreprises d’une manière conquérante.

[2] La région de Transylvanie, jadis intégrée à l’Empire austro-hongrois, a été rattachée à la Roumanie à l’issue du traité de Trianon de 1920.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

On reprend donc Raskolnikoff dans ces pages immortelles :

On reprend donc Raskolnikoff dans ces pages immortelles : « En un mot, je démontre que non seulement les grands hommes, mais tous ceux qui sortent tant soit peu de l’ornière, tous ceux qui sont capables de dire quelque chose de nouveau, même pas grand-chose, doivent, de par leur nature, être nécessairement plus ou moins des criminels. »

« En un mot, je démontre que non seulement les grands hommes, mais tous ceux qui sortent tant soit peu de l’ornière, tous ceux qui sont capables de dire quelque chose de nouveau, même pas grand-chose, doivent, de par leur nature, être nécessairement plus ou moins des criminels. »

Koudrine emploie des porte-parole à la Chambre des Comptes et dans une organisation politique qu’il entretient, le Comité d’Initiative Civile. Cette organisation, créée par Koudrine en 2012 à la suite de sa

Koudrine emploie des porte-parole à la Chambre des Comptes et dans une organisation politique qu’il entretient, le Comité d’Initiative Civile. Cette organisation, créée par Koudrine en 2012 à la suite de sa

George Friedman, dans son livre The Next 100 Years, dit que bientôt le but du contrôle militaire et politique de l’espace sera la mise en œuvre de satellites portant des armes de destruction massive. La miniaturisation des armes et de divers systèmes automatiques est en cours de réalisation. Les experts disent que bientôt les nouveaux nano- et pico-satellites auront un diamètre de 10 centimètres environ.

George Friedman, dans son livre The Next 100 Years, dit que bientôt le but du contrôle militaire et politique de l’espace sera la mise en œuvre de satellites portant des armes de destruction massive. La miniaturisation des armes et de divers systèmes automatiques est en cours de réalisation. Les experts disent que bientôt les nouveaux nano- et pico-satellites auront un diamètre de 10 centimètres environ.

- L’approche évaluative (A. Dugin, S. Kiselyov, L. Ivashov). Ses représentants adoptent la base du système évaluatif. Cette approche est la plus commune. Cette position est typique d’A. Dugin. Pour lui, la civilisation est une vaste et stable région géographique et culturelle, unie par des valeurs spirituelles, des attitudes stylistiques et psychologiques et une expérience historique communes. La plupart de ces régions coïncident avec les frontières de la diffusion des grandes religions mondiales. La structure de la civilisation peut inclure plusieurs Etats, mais il y a des cas où les frontières des civilisations traversent des Etats particuliers, les divisant en plusieurs parties [1].

- L’approche évaluative (A. Dugin, S. Kiselyov, L. Ivashov). Ses représentants adoptent la base du système évaluatif. Cette approche est la plus commune. Cette position est typique d’A. Dugin. Pour lui, la civilisation est une vaste et stable région géographique et culturelle, unie par des valeurs spirituelles, des attitudes stylistiques et psychologiques et une expérience historique communes. La plupart de ces régions coïncident avec les frontières de la diffusion des grandes religions mondiales. La structure de la civilisation peut inclure plusieurs Etats, mais il y a des cas où les frontières des civilisations traversent des Etats particuliers, les divisant en plusieurs parties [1]. Gumilev comprend l’ethnicité comme un groupe humain stable, naturellement formé, s’opposant à tous les autres groupes similaires, qui est déterminé par un sens de la complémentarité, et un genre différent de comportement stéréotypé, qui change régulièrement dans le temps historique [5].

Gumilev comprend l’ethnicité comme un groupe humain stable, naturellement formé, s’opposant à tous les autres groupes similaires, qui est déterminé par un sens de la complémentarité, et un genre différent de comportement stéréotypé, qui change régulièrement dans le temps historique [5].

Les Allemands ont pris 200.000 Turcs il y a cinquante ans. Maintenant ils sont 4 millions. Voilà. Les fans turcs sont les plus nombreux dans les stades allemands pour soutenir les équipes turques. Les Allemands ne peuvent plus soutenir leur propre équipe dans leur pays.

Les Allemands ont pris 200.000 Turcs il y a cinquante ans. Maintenant ils sont 4 millions. Voilà. Les fans turcs sont les plus nombreux dans les stades allemands pour soutenir les équipes turques. Les Allemands ne peuvent plus soutenir leur propre équipe dans leur pays.

Does this sound like it was written by an anti-Semite? Maybe it does to someone as dishonest and as blinkered as Cathy Young. Maybe it does to someone who wishes to enforce a program of mandatory philo-Semitism among the goyim. But to everyone else, it just seems like it was written by the same man who thirty years earlier told Russians they should “err . . . on the side of exaggeration” when it comes to repentance . . . but only if that repentance is mutual.

Does this sound like it was written by an anti-Semite? Maybe it does to someone as dishonest and as blinkered as Cathy Young. Maybe it does to someone who wishes to enforce a program of mandatory philo-Semitism among the goyim. But to everyone else, it just seems like it was written by the same man who thirty years earlier told Russians they should “err . . . on the side of exaggeration” when it comes to repentance . . . but only if that repentance is mutual.

Et c’est en regardant la question de la religion que l’on peut commencer à comprendre la Weltanschauung russe, l’Idée russe. L’Occident, pendant les derniers siècles, a lentement apostasié le christianisme, cette apostasie s’accélérant à partir des années 60. Aujourd’hui l’Occident souligne l’étendue de sa rébellion contre Dieu en célébrant des choses comme l’homosexualité, en appelant bien ce qui est mal et mal ce qui est bien.

Et c’est en regardant la question de la religion que l’on peut commencer à comprendre la Weltanschauung russe, l’Idée russe. L’Occident, pendant les derniers siècles, a lentement apostasié le christianisme, cette apostasie s’accélérant à partir des années 60. Aujourd’hui l’Occident souligne l’étendue de sa rébellion contre Dieu en célébrant des choses comme l’homosexualité, en appelant bien ce qui est mal et mal ce qui est bien. Berdiaev reproche à Nietzsche d’être une métonymie de l’Occident :

Berdiaev reproche à Nietzsche d’être une métonymie de l’Occident :

Nous voudrions seulement préciser une chose en ce qui concerne le centralisme revendiqué de cet auteur russe : si, pour notre part, nous nous faisons le défenseur d'un certain fédéralisme, nous nous devons néanmoins d'ajouter que celui-ci ne pourrait être, selon nous, désaccouplé d'une vision centraliste du pouvoir suprême par le fait de la considération spirituelle et traditionnelle qui motive et soutient celle-ci. L'indépendance ne saurait qu'être illusoire au regard de la dynamique de l'autonomie régionale et nationale (tout comme civilisationnelle) et, dans les faits, elle n'est qu'un voile destiné à camoufler une influence néfaste (réelle celle-là et destructrice de la diversité culturelle) sur la culture des peuples et sur leur singularité (l'américanisation sous-jacente au soutien déclaré à la « réappropriation » par les peuples minoritaires de leur culture et de leurs « droits », par exemple). Le centralisme est une nécessité au regard d'une dynamique culturelle qui n'est telle que parce qu'elle peut trouver à s'élever par rapport à un lieux spirituel et politique central, et ultime du point de vue de l'affirmation de sa propre singularité. Il ne peut y avoir de véritable progrès humain sans qu'il ne soit donné à un peuple, comme à une personne, la possibilité perpétuelle de pouvoir s'élever et s'affirmer par rapport aux Autres en regard d'un Ordre qui en donne la réelle possibilité sans encourir le chaos et, au final, l'extinction. La croissance d'une culture comme d'une personnalité est autant à considérer d'un point de vue horizontal que d'un point de vue vertical. Or, il n'est qu'une juste hiérarchie pour octroyer le réel pouvoir de s'élever parmi, et non à l'encontre, des Autres.

Nous voudrions seulement préciser une chose en ce qui concerne le centralisme revendiqué de cet auteur russe : si, pour notre part, nous nous faisons le défenseur d'un certain fédéralisme, nous nous devons néanmoins d'ajouter que celui-ci ne pourrait être, selon nous, désaccouplé d'une vision centraliste du pouvoir suprême par le fait de la considération spirituelle et traditionnelle qui motive et soutient celle-ci. L'indépendance ne saurait qu'être illusoire au regard de la dynamique de l'autonomie régionale et nationale (tout comme civilisationnelle) et, dans les faits, elle n'est qu'un voile destiné à camoufler une influence néfaste (réelle celle-là et destructrice de la diversité culturelle) sur la culture des peuples et sur leur singularité (l'américanisation sous-jacente au soutien déclaré à la « réappropriation » par les peuples minoritaires de leur culture et de leurs « droits », par exemple). Le centralisme est une nécessité au regard d'une dynamique culturelle qui n'est telle que parce qu'elle peut trouver à s'élever par rapport à un lieux spirituel et politique central, et ultime du point de vue de l'affirmation de sa propre singularité. Il ne peut y avoir de véritable progrès humain sans qu'il ne soit donné à un peuple, comme à une personne, la possibilité perpétuelle de pouvoir s'élever et s'affirmer par rapport aux Autres en regard d'un Ordre qui en donne la réelle possibilité sans encourir le chaos et, au final, l'extinction. La croissance d'une culture comme d'une personnalité est autant à considérer d'un point de vue horizontal que d'un point de vue vertical. Or, il n'est qu'une juste hiérarchie pour octroyer le réel pouvoir de s'élever parmi, et non à l'encontre, des Autres.

Question inévitable : après la séparation de ces tribus de la Russie, qui les prendra sous sa responsabilité ? Quelle puissance étrangère se jouera d’elles et en retirera la sève vitale ?

Question inévitable : après la séparation de ces tribus de la Russie, qui les prendra sous sa responsabilité ? Quelle puissance étrangère se jouera d’elles et en retirera la sève vitale ?