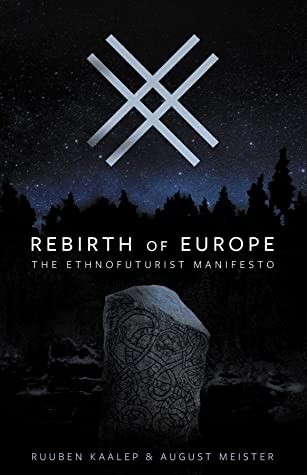

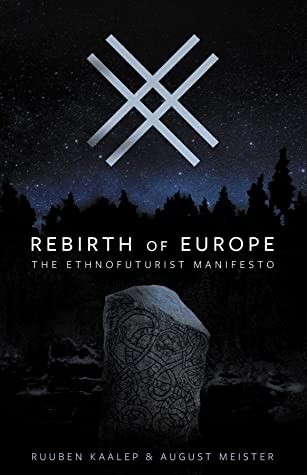

Ethnofuturisme ? Une recension de Rebirth of Europe

Andrew Joyce

Ruuben Kaalep & August Meister

Rebirth of Europe - The Ethnofuturist Manifesto

Arktos, 2020

Il existe de nombreuses façons de décrire l'époque dans laquelle nous vivons, et aucune n'est optimiste. C'est pourquoi je considère que ce n'est pas une mince affaire que Ruuben Kaalep et August Meister, deux jeunes ethnonationalistes des pays baltes, soient parvenus à élaborer un manifeste extrêmement positif, et même réjouissant, à partir des déchets puants et des engouements imbéciles de l'époque actuelle. H.L. Mencken a suggéré un jour que "tout gouvernement, dans son essence, est une conspiration contre l'homme supérieur". Le gouvernement moderne de l'Occident est une conspiration contre le seul homme blanc, et la question de savoir comment renverser cette conspiration est le plus grand défi de notre époque. Elle a donné lieu à une prolifération de manifestes et de façons de décrire notre politique, tous dans le but de renverser la vapeur sur le plan politique et de ramener à la raison la majorité des Européens, où qu'ils vivent dans le monde.

Ruuben Kaalep

Mais cette prolifération d'idées et de méthodes a probablement aggravé nos maux plutôt que de les soulager. Aujourd'hui, nous sommes confrontés à de la confusion: de nombreuses auto-suggestions ont été élaborées qui ne semblent qu'exacerber les factions. Et nous avons cuisiné un véritable ragoût de manifestes qui se contredisent les uns les autres ou suggèrent des points d'intérêt différents. Une grande partie de ce qui passe aujourd'hui pour la philosophie ethnonationaliste contemporaine, en particulier dans l'Anglosphère, est sous-tendue par une sorte de paralysie apathique, et exprime une attente de quelque chose d'indéfini mais néanmoins d'ardemment désiré. Je crois que la chose à laquelle nous aspirons le plus est la clarté et la confiance. La clarté de notre position. La clarté de ce qui nous arrive. La clarté de nos options. Et la confiance de voir ces options avancer dans nos sociétés. Kaalep et Meister réussissent là où d'autres échouent, car Rebirth of Europe est un chef-d'œuvre qui nous donne confiance et offre enfin de la clarté.

Ruuben Kaalep est un nationaliste estonien qui se décrit comme un ethnofuturiste. Il est l'un des fondateurs du mouvement de jeunesse Blue Awakening (Sinine Äratus) et du Parti populaire conservateur d'Estonie (EKRE). Il est également membre du Parlement estonien depuis 2019, où il appartient à la commission des affaires étrangères et préside le groupe chargé de plancher sur la liberté d'expression. À part cela, je ne sais pas grand-chose de lui, ce qui en dit plus sur mon ignorance des affaires relatives au nationalisme est-européen que sur l'étendue de ses activités.

Les images que nous trouvons de ce théoricien et parlementaire révèlent un jeune homme joyeux qui lui donne l'air d'un artiste excentrique, doté d'une sensibilité qui se retrouve dans ce livre sous la forme d'une confiance rhétorique excentrique et irrépressible. Kaalep a écrit Rebirth of Europe avec August Meister, qui semble être le pseudonyme d'un écrivain balte, expert en histoire et en politique, entre 2015 et 2017. Tous deux sont clairement talentueux, cultivés et bien formés. Bien que nous soyons maintenant près de quatre ans après la rédaction finale du texte, celui-ci n'a pas du tout vieilli puisqu'il s'abstient de discuter des menus détails de la politique contemporaine (il n'y a qu'une ou deux références fugaces à Trump, par exemple) au profit d'une vision beaucoup plus grande et plus large de la scène politique mondiale.

Rebirth of Europe est un texte court mais incroyablement subtil d'une centaine de pages, divisé en trois chapitres. Le premier chapitre, "La lutte de notre temps", est une description succincte des causes fondamentales et des manifestations patentes du déclin européen. Le deuxième chapitre, "Ethnofuturisme", est un appel à une politique ethnonationaliste prête à accepter pleinement la technologie et à avancer dans l'histoire. Le troisième chapitre, "Les aspects géopolitiques de l'ethnofuturisme", offre une vue d'ensemble des perspectives d'avenir de l'ethnonationalisme européen sur la scène internationale.

Le livre s'ouvre sur un grand style philosophique qui, dans son appel au "principe organique", m'a quelque peu rappelé l'ouverture d'Imperium de Yockey. Ce que le premier chapitre décrit pour l'essentiel, c'est l'état spirituel et politico-culturel d'une civilisation en crise. La crise européenne, comme nous ne le savons que trop bien, se déroule à de multiples niveaux, les Européens étant confrontés à l'emballement de la technologie, à des concepts d'individualisme renégats, à une migration de masse, à une subversion calculée, à la trahison et à la corruption internes, et à la perte de tout lien avec le passé. Ce dernier point est l'une des principales préoccupations de Kaalep et Meister, la solution proposée étant une tentative d'arraisonner l'avenir tout en intégrant des éléments du passé, en évitant les dérapages nostalgiques simplistes.

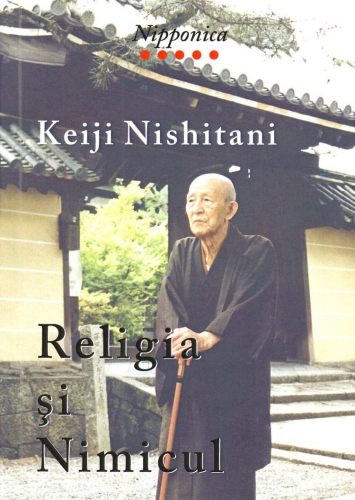

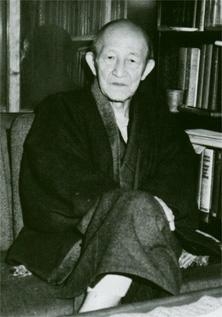

Dans un sens large, il s'agit d'une idée peu originale, et je veux dire par là que je félicite les auteurs plutôt que de les dénigrer. Ce que je veux souligner, c'est qu'une telle proposition ne doit pas être considérée comme du charlatanisme, ni même comme une pensée propre à une chapelle émanant de la marginalité politique. L'un des représentants les plus impressionnants et les plus profonds de cette approche est Keiji Nishitani (1900-1990), un disciple japonais de Martin Heidegger et l'un des principaux philosophes des religions du XXe siècle [1], qui s'est immergé profondément dans la philosophie européenne, et lui a témoigné un grand respect, tout en s'interrogeant sur ce que le modernisme et la technologie de l'Occident signifieraient en fin de compte pour sa propre civilisation.

Ce questionnement a finalement conduit Nishitani à s'opposer farouchement aux tendances nihilistes de la modernité européenne/occidentale (voir, par exemple, son ouvrage The Self-Overcoming of Nihilism), et à proposer quelque chose qui ressemble remarquablement à l'archéofuturisme défendu plus tard par feu Guillaume Faye et, en fait, par Kaalep et Meister dans le volume que je recense ici. Dans une série de conférences données à l'Association bouddhiste Shin à Kyoto entre 1971 et 1974, Nishitani a élaboré du sens face à la confrontation entre la culture japonaise et ces éléments du modernisme occidental que nous décririons aujourd'hui simplement comme le globalisme [2].

Nishitani a rejeté l'individualisme extrême, qui considère le Soi comme à la fois singulier et autonome - par opposition à singulier mais intégré dans une communauté et un héritage. Associée à la science et à la technologie, ainsi qu'à un matérialisme effréné, la vision individualiste extrême du Soi conduirait, selon Nishitani, à l'effondrement de toutes les relations humaines interpersonnelles significatives. L'athéisme matérialiste, incapable de placer l'individu dans le contexte plus large de l'univers comme lieu divin et source créatrice, conduirait à l'atrophie totale de la culture et à la régression de l'humanité. Le professeur Robert Carter, un spécialiste de Nishitani, souligne que:

La stratégie [de Nishitani] n'est pas de préconiser un retour au passé, car il est catégorique sur le fait que le passé est à jamais figé et hors de portée. Néanmoins, en tant qu'êtres humains, nous portons le passé en nous de bien des façons, et il nous incombe d'insuffler une nouvelle vie et une nouvelle signification à la tradition, alors qu'elle est façonnée et remodelée par la science, la technologie et les cultures occidentales. Il est partisan du changement, mais d'un changement qui n'oublie pas de porter son passé vers l'avenir comme un ingrédient du "mélange de sens" qu'une vie de qualité exige toujours. La personne authentique est celle qui vit dans le présent avec un œil sur le passé et un autre sur l'avenir, sur l'espoir et les possibilités. Nishitani pense que ce que l'on attend de nous dans le monde moderne et postmoderne, c'est que nous détruisions et reconstruisions simultanément notre mode de vie traditionnel à la lumière des changements induits par le siècle dans lequel nous nous trouvons. Cependant, nous ne devons pas simplement rejoindre les laïcs qui ont abandonné la religion et une grande partie de la tradition. Ils vivent aveuglément, au gré des tendances et des modes du moment. De plus, ils ont accepté et préféré un nihilisme omniprésent qui leur fait comprendre de manière rationnelle la vérité de la condition humaine et, ce faisant, ils ont perdu toute conscience d'un arrière-plan métaphysique et spirituel durable par rapport au premier plan matérialiste et nihiliste, appauvri, de nos existences.

Nishitani, qui suscite aujourd'hui une extrême prudence de la part des chercheurs contemporains en raison de son utilisation fréquente de l'allemand pour désigner "le sang et la terre" (Blut und Boden) et de son affirmation selon laquelle seules les civilisations européenne et est-asiatique peuvent être considérées comme prééminentes au niveau mondial [3], élabore une sorte d'ethnofuturisme sous forme poétique, en utilisant l'analogie du cerf-volant :

Elle concrétise ce qui vient d'être dit sur l'importance de la tradition pour avancer vers un nouvel avenir, et rencontrer de nouvelles circonstances, tout en restant fidèle au passé. ... Comme un cerf-volant, le Japon a pu maintenir un cap stable, grâce à la "queue" de la tradition qui a servi à stabiliser son vol dans les vents du changement, tout en étant enraciné ou ancré par la "corde" de sa culture profonde. Un cerf-volant qui n'a pas le poids de la tradition et de l'enracinement ne fait que danser sauvagement, s'empêtrant dans les branches des arbres, ou s'écrasant au sol, ou encore se détachant complètement et perdant son passé distinctif. Ce qui a fait du Japon un pays capable de s'adapter à sa propre modernisation de haut niveau, ce sont ses traditions profondément enracinées. Il en résulte une forme de progrès plus équilibrée et plus stable [par rapport à celle observée en Occident]. Lorsqu'un vent violent souffle, la force de la tradition doit être mise à contribution. Mais... on ne peut pas faire voler un cerf-volant si sa queue est trop lourde. Il est de la plus haute importance de trouver un équilibre entre ces deux inclinations : vers la modernisation et le changement, et vers la tradition.

La lutte de notre temps

Dans Rebirth of Europe, Kaalep et Meister font presque exactement écho aux sentiments de Nishitani et commencent leur texte en avançant l'argument selon lequel le "cerf-volant" européen s'est vu couper la ficelle et la queue, ce qui l'entraîne dans une spirale de chaos. Ce chaos est cultivé par des éléments mondialistes qui veulent couper les liens de toutes les nations avec leur histoire et leurs traditions et tentent d'écraser les patrimoines génétiques uniques des différents peuples en les recouvrant d'une culture totalitaire commune tissée de conformité. Kaalep et Meister insistent sur le fait que "au XXIe siècle, le conflit fondamental oppose le mondialisme et le nationalisme. ... La lutte de notre époque ne se manifeste pas tant comme une guerre avec des rangées de tombes entourées de coquelicots et avec des charges de cavalerie, mais comme une lutte culturelle. Le monde doit soit devenir un, dirigé par une culture de masse totalitaire, soit redevenir multiple - une diversité d'ethno-états uniques". Le couple affirme que "le véritable ethnonationaliste se soucie de toutes les nations, et le principe de l'ethnonationalisme vise à fournir à chaque nation une patrie. Le nôtre est donc une rébellion contre les principes du libéralisme, qui considère que chaque pays appartient à tout le monde - et donc à personne. Le nationalisme cherche à sauver le monde".

Au cœur de leur manifeste se trouve ce que Kaalep et Meister appellent "le principe organique", qui implique - une fois de plus en écho aux philosophies est-asiatiques de Nishitani et de l'école de philosophie de Kyoto à laquelle il était associé (mais avec des inflexions nietzschéennes et européennes pré-modernes) - "un principe de base non-duel de l'existence - la plus haute unité possible, au-delà du bien et du mal, qui intègre à la fois la réalité spirituelle et physique". Bien que cette rhétorique soit un peu trop tête en l'air à mon goût, elle est entrecoupée d'un langage suffisamment clair pour permettre à un lecteur peu familier avec la philosophie en question de retenir le message principal. En bref, Kaalep et Meister soutiennent que:

Au cœur de leur manifeste se trouve ce que Kaalep et Meister appellent "le principe organique", qui implique - une fois de plus en écho aux philosophies est-asiatiques de Nishitani et de l'école de philosophie de Kyoto à laquelle il était associé (mais avec des inflexions nietzschéennes et européennes pré-modernes) - "un principe de base non-duel de l'existence - la plus haute unité possible, au-delà du bien et du mal, qui intègre à la fois la réalité spirituelle et physique". Bien que cette rhétorique soit un peu trop tête en l'air à mon goût, elle est entrecoupée d'un langage suffisamment clair pour permettre à un lecteur peu familier avec la philosophie en question de retenir le message principal. En bref, Kaalep et Meister soutiennent que:

Notre monde est un combat permanent entre les forces spirituelles et physiques, entre les identités, les religions, les cultures, entre "nous" et "eux". Au fur et à mesure que la vie s'étend, elle surmonte les résistances, elle devient plus complexe et inégale, et le conflit et la lutte sont donc des contreparties de la vie elle-même. ... Cette dialectique pourrait très bien être appelée le "cercle de la vie". La vie existe dans le mouvement, la différenciation et l'inégalité. ... L'inégalité universelle est un facteur qui permet au monde d'être dynamique et d'évoluer, en donnant à chacun une chance de trouver sa place dans le tout organique. C'est le principe de non-discrimination de l'État organique, qui s'oppose à l'humanisme mécaniste, selon lequel l'individu est considéré comme "un rouage de la machine", remplaçable selon les besoins d'un projet de super-État ou les besoins du marché.

Kaalep et Meister consacrent une section intéressante à la hiérarchie dans les sociétés européennes historiques, en réfléchissant au fait que, si les anciens systèmes de castes sont aujourd'hui très décriés, ils étaient en fait transparents et socialement satisfaisants. Par contraste, nos élites d'aujourd'hui prospèrent sur le fait que,

Les hiérarchies mécanistes modernes sont secrètes et fondées sur un "mérite" purement matériel. ... Elles n'ont de comptes à rendre à personne, mais l'influence des niveaux supérieurs sur les niveaux inférieurs est totalitaire et sans aucun sens de la responsabilité éthique. Une hiérarchie verticale du pouvoir est établie ; les liens horizontaux sont affaiblis par des conflits internes et une idéologie de haine mutuelle, de compétition et d'individualisme, qui renforce le pouvoir des niveaux supérieurs. Le paradoxe aujourd'hui est le suivant : dans les conditions de l'idéologie de l'"égalité" totale, une quantité historiquement sans précédent de pouvoir appartient à ceux d'"en haut" par rapport à ceux d'"en bas". L'unicité historique de ce fait est liée au fait qu'aujourd'hui les technologies modernes et les moyens de communication de masse permettent un degré maximal de manipulation des masses d'hommes cosmopolites.

Kaalep et Meister, cependant, rejettent le pessimisme ou le désespoir, voyant dans l'accélération du libéralisme mondialiste simplement l'accélération nécessaire qui mènera à l'effondrement civilisationnel - une condition préalable à la renaissance. Pour les auteurs, "la renaissance de la civilisation est une possibilité toujours présente qui doit être comprise et réalisée". Ils insistent sur le fait que "le noyau métaphysique de notre civilisation et sa tradition intégrale, qui est profondément ethnique, se trouve actuellement en dessous, attendant le bon moment pour briser les structures artificielles de la civilisation postmoderne". Cette renaissance ne se caractérisera pas par un rejet total de la modernité, mais par la soumission de ses éléments mécanistes au principe organique: "la tâche de l'avenir est de dompter ces forces éveillées et de les mettre au service d'un objectif plus élevé - la création d'une nouvelle culture et d'un nouvel homme dont les racines restent profondément ancrées dans le sol européen et dont les yeux sont à nouveau tournés vers le ciel." Le livre procède à un examen détaillé du libéralisme en tant qu'idéologie mécaniste. On nous dit que "le libéralisme en tant que théorie est inséparable du mondialisme en tant que pouvoir" et qu'il se caractérise par une "révolution permanente" contre les traditions, les normes culturelles et la vie elle-même.

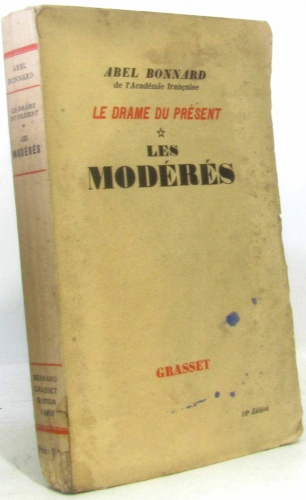

Le texte passe ensuite à une dénonciation approfondie, et plutôt excellente, du conservatisme, tout en incorporant et en critiquant les idées d'Edmund Burke, de Joseph de Maistre et de Nietzsche. L'accent est mis sur le fait que le simple conservatisme est une stratégie perdante puisque son exigence finale de garder les choses "telles qu'elles sont" conduira toujours à la décadence et au nihilisme. La seule voie véritable et naturelle à suivre est de s'engager dans une contre-révolution qui synthétise "les meilleurs éléments de la modernité et de la tradition".

Il va sans dire que Kaalep et Meister sont très favorables à la technologie, ce qui va à l'encontre de ceux qui, dans nos cercles, tendent davantage vers le type de pensée exposé par Ted Kaczynski et Pentti Linkola, ou vers les critiques de la pensée technologique que l'on peut trouver dans les écrits de Martin Heidegger ou Jacques Ellul. Je me compte parmi ceux que l'on pourrait décrire, au minimum, comme étant méfiants à l'égard du progrès technologique, ou du moins comme doutant de ses perspectives de progrès incessant étant donné la limitation éventuelle des ressources naturelles et le coût environnemental et social croissant de l'expansion technologique, en particulier entre les mains d'une élite mondialiste déterminée à imposer un État de surveillance et à imposer une conformité de masse. Même en dehors de certaines questions éthiques soulevées, par exemple, par la production génétique des êtres humains, la contamination massive de nos réserves d'eau par des produits chimiques industriels toxiques, qui a entraîné une baisse de la fertilité et des mutations dans le monde entier, devrait fournir à toute personne raisonnable une raison suffisante pour réfléchir sérieusement à ces problèmes actuels.

Cela dit, les considérations géopolitiques exigent que l'Europe/l'Occident reste au moins compétitif dans la sphère technologique, ce qui signifie que nous sommes probablement, dans un avenir prévisible, enfermés dans la course aux armements technologiques. Puisque nous ne pouvons pas nous en extraire, nous pouvons tout aussi bien tenter d'en prendre la tête. Dans ce cas, le problème qui se pose est celui de l'impact potentiel sur la nature de notre civilisation. Kaalep et Meister suggèrent que nous explorions les moyens de "relier la technologie moderne à l'ancienne façon d'être la plus inhérente à l'homme". Cela ressemble certainement à un idéal, mais à quoi cela ressemble-t-il en termes pratiques? Les auteurs n'offrent aucune réponse, mais je suppose que l'important est qu'ils mettent la question sous les projecteurs.

Le premier chapitre du livre se termine par un regard sur "le totalitarisme de la nouvelle gauche et le déclin de l'Occident". Les lecteurs de The Occidental Observer ne trouveront rien de particulièrement nouveau dans ce chapitre, mais certaines tournures de phrases mémorables résument très bien la situation dans laquelle nous nous trouvons :

Pour ce nouveau totalitarisme, les nations et les peuples sont considérés comme des obstacles qui doivent être éliminés et remplacés par un nouvel ordre mondial. ... Le monde le plus avantageux pour l'élite mondiale est celui où la valeur la plus élevée est l'individu, mais l'individu lui-même est libéré, avec l'aide du postmodernisme, de tout sens, de toute signification et de tout contexte plus large, et se retrouve isolé et vulnérable.

Après la Seconde Guerre mondiale, les populations occidentales ont été "bernées par les promesses de prospérité économique et d'innombrables libertés, remarquant rarement que la liberté de rester qui vous êtes n'était pas sur la table." De façon magistrale, nos auteurs écrivent

Les gouvernements et les entreprises sont devenus gigantesques et inhumains, mais la démocratie dans les questions essentielles ne fonctionne tout simplement pas. En effet, là où elle est tentée, cette sorte de démocratie ne sert qu'à aliéner davantage l'homme. La conséquence générale est un sentiment universel de vide et de stress pour les humains qui ont déjà perdu tout lien avec la nature et tout contrôle sur le processus technologique. Les humains qui ne remplissent plus que le rôle de travailleurs-employeurs cherchent leur identité dans les tendances de la mode d'un jour offertes par la culture de consommation. Cette culture crée des humains incapables de réagir les uns avec les autres en tant que personnalités matures. L'illusion d'une "révolution de la jeunesse" constante est créée, alors que les jeunes ne font que recréer passivement les modèles de comportement proposés par les élites mondialistes ; ils font à leur tour partie des tendances générales du système.

Plus loin,

Nous avons même perdu la trace de qui nous sommes, car aucune véritable identité ne peut exister dans une société de consommation. En apparence, tout le monde peut être spécial, libéré de tous les carcans de la tradition ; chacun peut s'identifier comme qui il veut. Ainsi, on ne naît pas avec une identité particulière. Si tout le monde peut être français, personne ne l'est vraiment. Lorsque le libéralisme parle de diversité, il vise en réalité à effacer toutes les distinctions. Lorsqu'il parle de multiculturalisme, il vise à créer un melting-pot mondial où aucune culture ne survit.

Dans sa dernière attaque contre la culture européenne, le libéralisme organise le remplacement physique des Européens par des personnes issues d'autres cultures. "C'est l'immigration de masse en nombre catastrophique". Mais avec ce pari, le libéralisme "est proche de sa grande finale". Nos auteurs insistent sur le fait que le libéralisme se consumera lui-même dans le processus, et qu'il est "sur le point de devenir une notion absurde, où même les valeurs qu'il a lui-même défendues commencent à être reconstruites par son idéologie métamorphosée". À ce moment-là, nous trouverons "notre chance de commencer un nouveau cycle culturel européen qui façonne son histoire pour de nombreux siècles à venir. Les libéraux seront impuissants à l'arrêter. Ils deviendront alors des conservateurs, refusant obstinément d'accepter la nouvelle réalité dans laquelle les nationalistes vont s'engager." Ce nationalisme devra être d'un type totalement nouveau : l'ethnofuturisme.

Ethnofuturisme

L'ethnofuturisme est un type de nationalisme qui transcende l'égoïsme national. Il ne cherche pas simplement à "conserver", car cela implique une défense statique alors que "la vie n'existe que dans le mouvement". Il trouve toutefois ses racines dans la révolution conservatrice proposée en Allemagne au début du XXe siècle et cherche à promouvoir une renaissance des "archétypes de la civilisation occidentale et des formes de vie oubliées qui ont formé notre civilisation en premier lieu". Les politiques d'immigration désastreuses, qui sont devenues un élément unificateur pour tous les nationalistes européens, signifient que l'Europe dans son ensemble "sera obligée de revenir aux valeurs traditionnelles et au nationalisme pour survivre." L'Amérique sera de plus en plus accablée par les conflits ethniques, mettant fin au "rêve américain" de construire une société dans laquelle l'héritage ancestral ne joue aucun rôle - "mais c'est inévitable, car une civilisation qui nie ces vérités fondamentales sera toujours vouée à l'effondrement." Kaalep et Meister poursuivent ,

La base fondamentale d'une nouvelle Europe doit être le nationalisme ethnique. Cela signifie que l'importance d'une nation en tant que tout organique doit être maintenue. ... En outre, la nature et les paysages de l'Europe doivent être préservés, car ils sont essentiels au patrimoine culturel et aux différences entre les peuples. La survie démographique de chaque nation doit être assurée par des politiques gouvernementales.

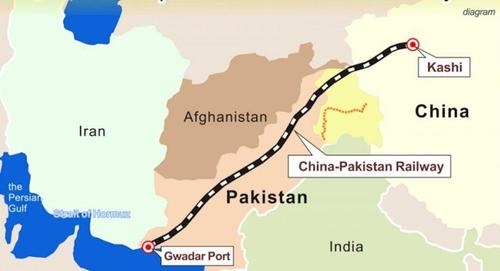

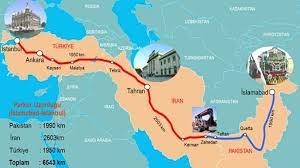

Alors que l'Europe occidentale risque de subir des dommages catastrophiques dus à l'immigration massive et à la guerre civile qui s'ensuivra inévitablement, "cette nouvelle Europe - et le nouvel Occident - pourrait avoir pour centres de sa culture Budapest, Varsovie et Tallinn. En maîtrisant ses processus démographiques et en ne les laissant pas entre les mains du libéralisme, la nouvelle Europe sera réellement capable de rivaliser économiquement et culturellement avec le reste du monde... Après avoir sécurisé son ethnē, le destin de l'Europe au XXIe siècle sera décidé par l'eugénisme national, et actuellement, seule la Chine semble avoir un état d'esprit approprié." La Hongrie est louée pour son récent programme de construction d'un réseau de chemins de fer à voie étroite qui met l'accent sur la vie à la campagne, et dont aucune multinationale n'a à tirer profit. Nos auteurs soulignent qu'il s'agit là "d'un signe de l'une des tâches les plus ethnofuturistes jamais développées par un pays au 21e siècle. La technologie moderne et la rapidité permettent de combiner les avantages de la ville et de la campagne."

Kaalep et Meister sont d'accord avec mon affirmation selon laquelle nous sommes plus ou moins enfermés dans une course aux armements technologiques. Ils soulignent que les progrès de la biotechnologie et des nanomatériaux ont "le potentiel de changer l'économie et la guerre d'ici la fin du siècle au-delà de toute reconnaissance. ... Se battre contre une telle technologie serait voué à l'échec et même dangereux. Le premier gouvernement, société ou groupe qui maîtrisera la biotechnologie aura inévitablement un énorme avantage sur tous ses rivaux." Les nationalistes européens doivent travailler ensemble car, à la fin du siècle, "le contrôle de la technologie doit être entre les mains des ethnonationalistes, et non des mondialistes, à supposer qu'ils aient survécu si longtemps."

De là, le texte passe à l'élaboration des raisons de rejeter toute alliance avec le conservatisme économique de type Buckley, dominant aux États-Unis parmi les républicains, et de rejeter la Nouvelle Droite associée à Alain de Benoist qui s'est formée dans la France des années 1960. Les auteurs reprochent à cette dernière de promouvoir "des idées abstraites sur les communes organiques et les droits des personnes à conserver leur identité", car cela "peut conduire à l'approbation du multiculturalisme." La Nouvelle Droite est également attaquée pour avoir dépensé "une grande partie de son énergie à lutter contre le christianisme", s'aliénant ainsi une partie importante de sa base de soutien. La Nouvelle Droite est également fortement critiquée pour son soutien à l'URSS et son antiaméricanisme strident, ainsi que pour avoir négligé de développer une théorie politique claire et une pratique correspondante. Kaalep et Meister rejettent l'idée que nous pouvons concentrer nos efforts sur la conquête d'une hégémonie culturelle sans apporter de résultats pratiques, en ne produisant que des publications et des conférences sans fin qui apportent un riche matériel intellectuel sans apporter de réels changements dans la vie des Européens.

Les aspects géopolitiques de l'ethnofuturisme

Ma section préférée de Rebirth of Europe est le dernier chapitre, qui offre un aperçu fascinant de la spéculation informée sur notre avenir en devenir. Le chapitre s'ouvre sur l'affirmation selon laquelle

nous revenons à la situation qui a précédé la révolution industrielle, dans laquelle la force économique sera déterminée par les ressources naturelles et démographiques, parce que le développement technologique sera fondamentalement le même pour toutes les nations du monde. Cela implique l'inévitabilité de la multipolarité et le retour au statut de superpuissance pour des civilisations comme la Chine et l'Inde.

Kaalep et Meister voient, dans la fin de l'hégémonie américaine, la fin du matérialisme mécaniste occidental qu'elle symbolise. De même, ils dénoncent l'idée eurasiste d'Alexandre Douguine car elle "ne peut pas fonctionner". La Russie n'est capable de combattre le marxisme culturel que dans les slogans, mais pas dans la pratique. La Russie "surpasse la décadence occidentale, avec des taux impressionnants d'avortements, d'alcoolisme et de toxicomanie, que son régime politique n'a pas pu, ou n'a pas voulu, arrêter. ... Les enfants des politiciens russes vivent à l'Ouest, et la culture de la Russie elle-même est surchargée d'émissions de télé-réalité et de culture de masse vulgaire."

Kaalep et Meister ajoutent,

Ce ne seront ni la Russie ni les États-Unis qui dirigeront l'avenir ; nous pouvons plutôt nous attendre à une nouvelle ère du Pacifique avec la Chine et l'Inde qui regagnent leur influence. Ces pays, au moins, ne seront pas libéraux, pacifistes ou humanistes - ils utiliseront les percées scientifiques au service de leur grandeur politique. Par conséquent, les peuples européens devront changer leur vision du monde afin de survivre dans cette nouvelle compétition, où nous perdons à chaque instant que nous faisons partie d'un système libéral, haineux et autodestructeur.

Il y a une section très intéressante concernant l'expérience nationaliste dans les États baltes, qui est soulignée par un très fort sentiment de fraternité européenne. Lorsque Kaalep et Meister affirment que les nationalistes baltes feront tout leur possible s'ils sont appelés à défendre les frontières méridionales de l'Europe ou l'intégrité démographique des nations d'Europe occidentale, on perçoit la plus grande sincérité.

Les remarques finales du livre, plutôt émouvantes, portent sur le devoir et la mort, conclusion de tout cheminement spirituel. "En fin de compte, mener un combat qui semble déjà perdu dès le départ est la seule chose à faire, précisément parce que rien d'autre ne compte. Rien ne compte plus que cela." Nos auteurs terminent en soutenant que,

Dans la situation actuelle de la civilisation occidentale, qui semble connaître une chute irréversible, s'arrêter n'est pas une option. Il ne s'agit pas seulement d'une question d'idéologies politiques, mais de la logique interne d'une culture. La seule chose qui reste à nos nations est de survivre à cette chute. Plus important encore, nos gènes et les traditions qui portent notre plein potentiel doivent survivre. Car la mort et la destruction de l'Occident, provoquées par le libéralisme, s'approchent toujours plus de leur objectif singulier. Lorsqu'elle atteindra un certain point, ce sera notre chance. Ce sera le moment d'un véritable retour aux sources, un retour sans jamais se retourner. Lorsque le monde occidental célébrait la diversité et le multiculturalisme, nous prévoyions sa destruction catastrophique par ses propres moyens. De plus, lorsqu'il commencera à paniquer devant la catastrophe qu'il n'a pu éviter, il sera alors temps pour nous de construire une nouvelle civilisation européenne. La boucle sera bouclée.

Remarques finales

Rebirth of Europe est un document rafraîchissant et optimiste qui, pour un livre d'une longueur aussi modeste, est bien au-dessus de son poids. Il présente une profondeur, une ampleur et une clarté de compréhension philosophique qui sont souvent rares dans des textes de cette nature, et le moins que l'on puisse dire, c'est qu'il donne à réfléchir. Les questions qu'il soulève exigent l'attention et l'action de toute personne concernée par la cause ethnonationaliste.

Reste à savoir si l'ethnofuturisme est une voie fiable à long terme. À part la Chine peut-être, voyons-nous vraiment dans le monde actuel un exemple de pays qui a réussi à maintenir des éléments significatifs de la culture traditionnelle tout en plongeant tête baissée dans le développement technologique ? Pour ma part, je suis sûr que si Keiji Nishitani avait prononcé ses conférences aujourd'hui, quelque 50 ans après s'être adressé à l'Association bouddhiste shin, il aurait peut-être été plus prudent dans son plaidoyer pour laisser le "cerf-volant" national s'envoler dans le vent du changement. Le Japon d'aujourd'hui est peut-être superficiellement stable et technologiquement avancé, mais il est en proie depuis des décennies à une faible fécondité et à des taux de suicide élevés, ainsi qu'à une marginalisation croissante de ses traditions et de ses religions.

Reste à savoir si l'ethnofuturisme est une voie fiable à long terme. À part la Chine peut-être, voyons-nous vraiment dans le monde actuel un exemple de pays qui a réussi à maintenir des éléments significatifs de la culture traditionnelle tout en plongeant tête baissée dans le développement technologique ? Pour ma part, je suis sûr que si Keiji Nishitani avait prononcé ses conférences aujourd'hui, quelque 50 ans après s'être adressé à l'Association bouddhiste shin, il aurait peut-être été plus prudent dans son plaidoyer pour laisser le "cerf-volant" national s'envoler dans le vent du changement. Le Japon d'aujourd'hui est peut-être superficiellement stable et technologiquement avancé, mais il est en proie depuis des décennies à une faible fécondité et à des taux de suicide élevés, ainsi qu'à une marginalisation croissante de ses traditions et de ses religions.

Le train fou de la modernité industrielle pourra-t-il un jour être suffisamment apprivoisé pour être conduit par la tradition ? Cela reste à voir. À ce problème s'ajoute, bien sûr, la question des éléments étrangers ancrés dans l'Occident qui s'emploient à faire en sorte que "la corde et la queue" du "cerf-volant" européen restent à jamais coupées. Comment un mouvement national peut-il reconnecter un peuple avec son histoire et ses traditions tout en abritant des factions qui veulent que ces mêmes traditions et histoires disparaissent à jamais ou soient définitivement ternies par la honte ? Peut-être le seul réconfort que nous pouvons tirer est, comme Kaalep et Meister le soulignent, le fait que même dans la catastrophe il peut y avoir une opportunité.

Notes:

[1] Voir, par exemple, son monumental Religion et néant.

[2] Pour les conférences complètes, voir K. Nishitani, On Buddhism (New York : State University of New York Press, 2006), 18.

[3] G. Parkes, " The Putative Fascism of the Kyoto School and the Political Correctness of the Modern Academy ", Philosophy East and West 47, no. 3 (1997) : 305-36. Pour une exploration plus biographique de l'anti-marxisme et du traditionalisme au sein de l'école de Kyoto, voir K. Nishitani, Nishida Kitaro : The Man and His Thought (Nagoya : Chisokudo Publications, 2016).

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Au cœur de leur manifeste se trouve ce que Kaalep et Meister appellent "le principe organique", qui implique - une fois de plus en écho aux philosophies est-asiatiques de Nishitani et de l'école de philosophie de Kyoto à laquelle il était associé (mais avec des inflexions nietzschéennes et européennes pré-modernes) - "un principe de base non-duel de l'existence - la plus haute unité possible, au-delà du bien et du mal, qui intègre à la fois la réalité spirituelle et physique". Bien que cette rhétorique soit un peu trop tête en l'air à mon goût, elle est entrecoupée d'un langage suffisamment clair pour permettre à un lecteur peu familier avec la philosophie en question de retenir le message principal. En bref, Kaalep et Meister soutiennent que:

Au cœur de leur manifeste se trouve ce que Kaalep et Meister appellent "le principe organique", qui implique - une fois de plus en écho aux philosophies est-asiatiques de Nishitani et de l'école de philosophie de Kyoto à laquelle il était associé (mais avec des inflexions nietzschéennes et européennes pré-modernes) - "un principe de base non-duel de l'existence - la plus haute unité possible, au-delà du bien et du mal, qui intègre à la fois la réalité spirituelle et physique". Bien que cette rhétorique soit un peu trop tête en l'air à mon goût, elle est entrecoupée d'un langage suffisamment clair pour permettre à un lecteur peu familier avec la philosophie en question de retenir le message principal. En bref, Kaalep et Meister soutiennent que:

Reste à savoir si l'ethnofuturisme est une voie fiable à long terme. À part la Chine peut-être, voyons-nous vraiment dans le monde actuel un exemple de pays qui a réussi à maintenir des éléments significatifs de la culture traditionnelle tout en plongeant tête baissée dans le développement technologique ? Pour ma part, je suis sûr que si Keiji Nishitani avait prononcé ses conférences aujourd'hui, quelque 50 ans après s'être adressé à l'Association bouddhiste shin, il aurait peut-être été plus prudent dans son plaidoyer pour laisser le "cerf-volant" national s'envoler dans le vent du changement. Le Japon d'aujourd'hui est peut-être superficiellement stable et technologiquement avancé, mais il est en proie depuis des décennies à une faible fécondité et à des taux de suicide élevés, ainsi qu'à une marginalisation croissante de ses traditions et de ses religions.

Reste à savoir si l'ethnofuturisme est une voie fiable à long terme. À part la Chine peut-être, voyons-nous vraiment dans le monde actuel un exemple de pays qui a réussi à maintenir des éléments significatifs de la culture traditionnelle tout en plongeant tête baissée dans le développement technologique ? Pour ma part, je suis sûr que si Keiji Nishitani avait prononcé ses conférences aujourd'hui, quelque 50 ans après s'être adressé à l'Association bouddhiste shin, il aurait peut-être été plus prudent dans son plaidoyer pour laisser le "cerf-volant" national s'envoler dans le vent du changement. Le Japon d'aujourd'hui est peut-être superficiellement stable et technologiquement avancé, mais il est en proie depuis des décennies à une faible fécondité et à des taux de suicide élevés, ainsi qu'à une marginalisation croissante de ses traditions et de ses religions.

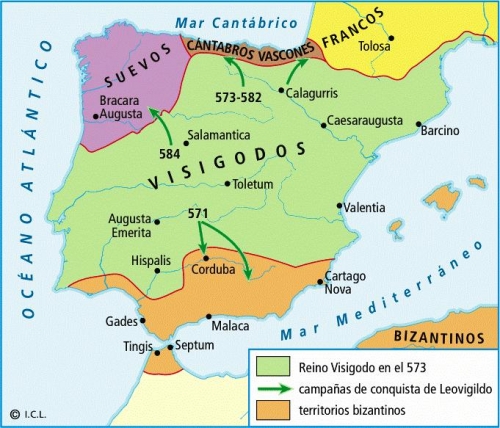

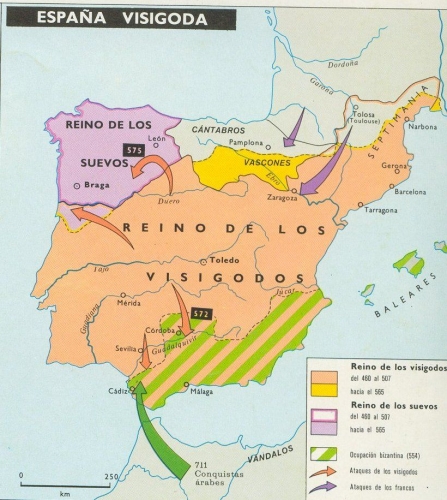

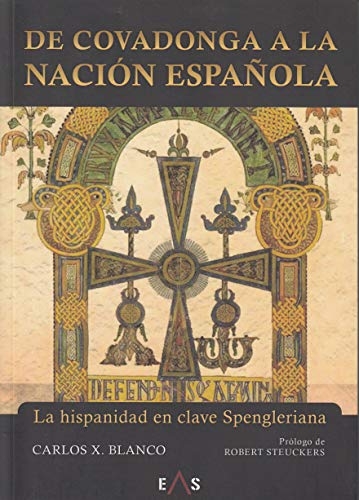

L'ouvrage que nous allons recenser, De covadonga a la nación española, de Carlos X Blanco, possède déjà un titre suffisamment suggestif qui invite à la lecture et suscite un grand intérêt, surtout quand on lit le sous-titre qui l'accompagne, "La hispanidad en clave spengleriana"; dans l'introduction Robert Steuckers commence déjà à exposer certaines des idées qui seront développées tout au long du livre. Dès le départ, une dualité décisive s'instaure dans la configuration toujours actuelle que l'Espagne acquerra au fil des siècles, une empreinte indélébile qui a conditionné le développement de la plus ancienne nation d'Europe occidentale, cette dualité apparaît clairement, avec l'existence de deux pôles ou deux âmes, de deux visions du monde opposées et conflictuelles : d'une part, celle représentée par les peuples du nord-ouest de la péninsule, pionniers et artisans des premières étapes de la Reconquête depuis le Royaume des Asturies, marquée par la présence d'un important élément celto-germanique, également romanisé mais sans le poids décadent et crépusculaire des civilisations précédentes, et d'autre part, les peuples hispano-romains du Levant et du sud de la péninsule, qui sont tombés sous la domination arabe et ont pris forme sous un modèle de civilisation différent, marqué par l'influence de civilisations disparues ou tombées en déclin, comme les civilisations romaine, byzantine ou arabe. C'est précisément cette antithèse qui forme la colonne vertébrale du livre, dans lequel l'auteur, Carlos X Blanco, utilise les théories et les interprétations du célèbre philosophe allemand de l'histoire Oswald Spengler et de son œuvre monumentale Le déclin de l'Occident.

L'ouvrage que nous allons recenser, De covadonga a la nación española, de Carlos X Blanco, possède déjà un titre suffisamment suggestif qui invite à la lecture et suscite un grand intérêt, surtout quand on lit le sous-titre qui l'accompagne, "La hispanidad en clave spengleriana"; dans l'introduction Robert Steuckers commence déjà à exposer certaines des idées qui seront développées tout au long du livre. Dès le départ, une dualité décisive s'instaure dans la configuration toujours actuelle que l'Espagne acquerra au fil des siècles, une empreinte indélébile qui a conditionné le développement de la plus ancienne nation d'Europe occidentale, cette dualité apparaît clairement, avec l'existence de deux pôles ou deux âmes, de deux visions du monde opposées et conflictuelles : d'une part, celle représentée par les peuples du nord-ouest de la péninsule, pionniers et artisans des premières étapes de la Reconquête depuis le Royaume des Asturies, marquée par la présence d'un important élément celto-germanique, également romanisé mais sans le poids décadent et crépusculaire des civilisations précédentes, et d'autre part, les peuples hispano-romains du Levant et du sud de la péninsule, qui sont tombés sous la domination arabe et ont pris forme sous un modèle de civilisation différent, marqué par l'influence de civilisations disparues ou tombées en déclin, comme les civilisations romaine, byzantine ou arabe. C'est précisément cette antithèse qui forme la colonne vertébrale du livre, dans lequel l'auteur, Carlos X Blanco, utilise les théories et les interprétations du célèbre philosophe allemand de l'histoire Oswald Spengler et de son œuvre monumentale Le déclin de l'Occident.