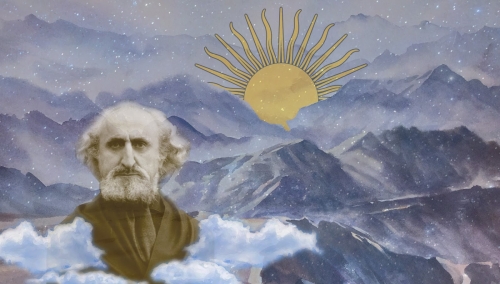

Hommage à Henry Corbin

Clavis hermeneutica

par Luc-Olivier d'Algange

La philosophie est cheminement, ou plus exactement, comme le disait Heidegger, « acheminement vers la parole ». Ce qui est dit porte en soi un long parcours, une pérégrination, à la fois historique et spirituelle. Avant de parvenir à l'oreille de celui à qui elle s'adresse, la parole humaine accomplit un voyage qui la conduit des sources du Logos jusqu'à l'entendement humain. Ce voyage, à maints égards, ressemble à une Odyssée. Dans l'éclaircie de la présence de la chose dite frémissent des clartés immémoriales, des songes et des visions. Toute spéculation philosophique témoigne, en son miroitement étymologique, d'une vision qui n'appartient ni entièrement au monde sensible, ni entièrement au monde intelligible, mais participe de l'un et de l'autre en les unissant, selon la formule de Platon, « par des gradations infinies ». L’idée est à la fois la « chose vue », l’Idea au sens grec, la forme, et la « cause » qui nous donne à voir. De même que la parole ne se situe ni exactement dans la bouche de celui qui parle ni exactement dans l'oreille de celui qui entend, mais entre eux, le monde imaginal, qui sera au principe de l'herméneutique corbinienne, se situe entre l'Intelligible et le sensible, donnant ainsi accès à la fois à l'un et à l'autre et favorisant ainsi l'étude historique la mieux étayée non moins que l'interprétation spirituelle la plus précise.

On pourrait, par analogie, transposer ce qu'à propos de Mallarmé, Charles Mauron nomma le « symbolisme du drame solaire ». De l'Occident extrême, crépusculaire, de Sein und Zeit, de la méditation allemande du déclin de l'Occident, une pérégrination débute, qui conduit, à travers l'œuvre-au-noir et la mise-en-demeure de « l’être pour la mort » à l'aurora consurgens de la « renaissance immortalisante ». Point de rupture, ni de renversement, ici, mais un patient approfondissement de la question. Le crépuscule inquiétant des poèmes de Trakl, la « lumière noire » de la foudre d'Apollon des poèmes d'Hölderlin, ne contredisent point mais annoncent l'âme d'azur, « dis-cédée », et la terre céleste dans le resplendissement du Logos. Le crépuscule détient le secret de l'aurore, l'extrême Occident tient, dans son déclin, le secret de la sagesse orientale. Au philosophe, pour qui, je cite, « les variations linguistiques ne sont que des incidents de parcours, ne signalent que des variantes topographiques d'importance secondaires », l'art de l'interprétation sera une attention matutinale. A l'orée des signes, entre le jour et la nuit, sur la lisière impondérable, il n'est pas impossible que le secret de l'aube et le secret du crépuscule, le secret de l'Occident et le secret de l'Orient soient un seul un même secret. L'attention herméneutique guette cet instant où le Sens s'empourpre comme l'Archange dont parle le Traité de Sohravardî.

On pourrait, par analogie, transposer ce qu'à propos de Mallarmé, Charles Mauron nomma le « symbolisme du drame solaire ». De l'Occident extrême, crépusculaire, de Sein und Zeit, de la méditation allemande du déclin de l'Occident, une pérégrination débute, qui conduit, à travers l'œuvre-au-noir et la mise-en-demeure de « l’être pour la mort » à l'aurora consurgens de la « renaissance immortalisante ». Point de rupture, ni de renversement, ici, mais un patient approfondissement de la question. Le crépuscule inquiétant des poèmes de Trakl, la « lumière noire » de la foudre d'Apollon des poèmes d'Hölderlin, ne contredisent point mais annoncent l'âme d'azur, « dis-cédée », et la terre céleste dans le resplendissement du Logos. Le crépuscule détient le secret de l'aurore, l'extrême Occident tient, dans son déclin, le secret de la sagesse orientale. Au philosophe, pour qui, je cite, « les variations linguistiques ne sont que des incidents de parcours, ne signalent que des variantes topographiques d'importance secondaires », l'art de l'interprétation sera une attention matutinale. A l'orée des signes, entre le jour et la nuit, sur la lisière impondérable, il n'est pas impossible que le secret de l'aube et le secret du crépuscule, le secret de l'Occident et le secret de l'Orient soient un seul un même secret. L'attention herméneutique guette cet instant où le Sens s'empourpre comme l'Archange dont parle le Traité de Sohravardî.

Cet Archange empourpré, dont une aile est blanche et l'autre noire, dont l'envol repose à la fois sur le jour et sur la nuit, est le Sens lui-même qui se refuse à l'exclusive ou à la division. Opposer l'Orient et l'Occident, ce serait ainsi refuser le drame solaire du Logos lui-même, découronner le Logos, le réduire à n'être qu'une monnaie d'échange, un or irradié, dont la valeur est attribuée, utilitaire au lieu d'être un or irradiant, donateur et philosophal, forgé dans l'œuvre-au-rouge de l'herméneutique. Tout homme habitué au patient compagnonnage avec des textes lointains ou difficiles connaît ce moment de l'éclaircie, où le Sens s'exhausse de sa gangue, où les signes s'irisent, où l'exil devient la fine pointe des retrouvailles. Après avoir affronté les tempêtes et le silence des vents, l'excès du mouvement comme l'excès de l'immobilité, la houle et la désespérance du navire encalminé, après avoir déjoué les ruses de Calypso, les asiles fallacieux, et la nuit et le jour également aveuglants, l'odyssée herméneutique entrevoit le retour à la question d'origine, enfin déployée comme une voile heureuse. L'acheminement se distingue du simple cheminement. L'herméneute s'achemine vers: il ne vagabonde point, il pèlerine vers le secret de la question qu'il se pose au commencement. Il ne fuit point, ne s'éloigne point, mais s'approche au plus près du Dire dans la chose dite, de l'essence même du Logos qui parle à travers lui.

Toute herméneutique est donc odysséenne, par provenance et destination. Elle l'est par provenance, comme en témoigne le catalogue des œuvres détruites par le feu de la bibliothèque d'Alexandrie dont une grande part fut consacrée à la méditation du « logos intérieur » (selon la formule du Philon d'Alexandrie) de l'Odyssée, et dont quelques fragments nous demeurent, tel que L'Antre des Nymphes de Porphyre. L'Orient, comme l'Occident demeure spolié de cet héritage de l'herméneutique alexandrine où s'opéra la fécondation mutuelle du Logos grec et de la sagesse hébraïque. L'herméneutique est odysséenne par destination en ce qu'elle ne cesse de vouloir retrouver dans l'oméga, le sens de l'alpha initial. Pour l'herméneute, l'horizon du voyage est le retour. La ligne ultime, celle de l'horizon, comme « l'heure treizième » du sonnet de Gérard de Nerval, est aussi et toujours la première ligne de ce livre originel que figurent les rouleaux de la mer. L'herméneute, pour s'avancer sur les abysses, dont les couleurs assombries sont elles-mêmes l'interprétation de la lumière du ciel, pour s'orienter dans les étendues qui lui paraissent infinies, ne dispose que du sextant de son entendement qu'il sait faillible, dont il sait qu'il n'est qu'un instrument,- ce qui lui épargnera l'hybris de la raison qui omet de s'interroger sur elle-même et les errances du discours subjectif qui perd de vue l'alpha et l'oméga et restreint le sens dans l'aléatoire, l'éphémère et l'accidentel.

Toute herméneutique est donc odysséenne, par provenance et destination. Elle l'est par provenance, comme en témoigne le catalogue des œuvres détruites par le feu de la bibliothèque d'Alexandrie dont une grande part fut consacrée à la méditation du « logos intérieur » (selon la formule du Philon d'Alexandrie) de l'Odyssée, et dont quelques fragments nous demeurent, tel que L'Antre des Nymphes de Porphyre. L'Orient, comme l'Occident demeure spolié de cet héritage de l'herméneutique alexandrine où s'opéra la fécondation mutuelle du Logos grec et de la sagesse hébraïque. L'herméneutique est odysséenne par destination en ce qu'elle ne cesse de vouloir retrouver dans l'oméga, le sens de l'alpha initial. Pour l'herméneute, l'horizon du voyage est le retour. La ligne ultime, celle de l'horizon, comme « l'heure treizième » du sonnet de Gérard de Nerval, est aussi et toujours la première ligne de ce livre originel que figurent les rouleaux de la mer. L'herméneute, pour s'avancer sur les abysses, dont les couleurs assombries sont elles-mêmes l'interprétation de la lumière du ciel, pour s'orienter dans les étendues qui lui paraissent infinies, ne dispose que du sextant de son entendement qu'il sait faillible, dont il sait qu'il n'est qu'un instrument,- ce qui lui épargnera l'hybris de la raison qui omet de s'interroger sur elle-même et les errances du discours subjectif qui perd de vue l'alpha et l'oméga et restreint le sens dans l'aléatoire, l'éphémère et l'accidentel.

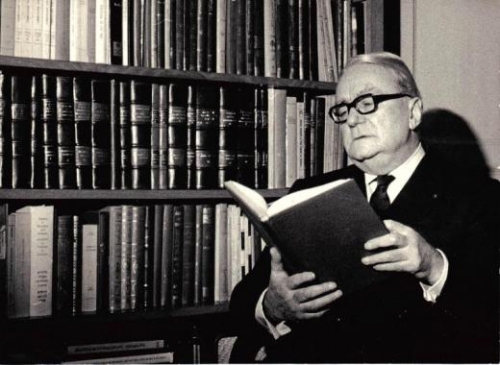

Ainsi devons-nous à Henry Corbin, non seulement la lumière faite sur des pans méconnus des cultures orientales et occidentales mais aussi le recouvrance de l'Art herméneutique à sa fine pointe, qui au-delà de l'exposition et de l'explication, serait une nouvelle implication du lecteur dans l'écrit qui se déroule sous ses yeux. Loin de considérer les œuvres de Mollâ Sadrâ ou de Ruzbéhan de Shîraz comme des objets culturels, délimités par l'histoire et la géographie, et dont nous séparerait à jamais la doxa de notre temps, Henry Corbin nous restitue à elles, à notre possibilité de les comprendre (dont dépend la possibilité de nous comprendre nous-mêmes), à cette implication, plus pointue que toute explication, à cette gnosis qui, je cite « convertit en jour cette nuit qui pourtant est toujours là, mais qui est une nuit de lumière ». « Ainsi donc, écrit Henry Corbin, lorsqu'il nous arrive de mettre en épigraphe les mots Ex oriente lux, nous nous tromperions du tout au tout en croyant dire la même chose que les Spirituels dont il sera question ici, si, pour guetter cette lumière de l'Orient, nous nous contentions de nous tourner vers l'orient géographique. Car, lorsque nous parlons du Soleil se levant à l'orient, cela réfère à la lumière du jour qui succède à la nuit. Le jour alterne avec la nuit, comme alternent deux contrastes qui, par essence, ne peuvent coexister. Lumière se levant à l'orient, et lumière déclinant à l'occident: deux prémonitions d'une option existentielle entre le monde du Jour et ses normes et le monde de la nuit, avec sa passion profonde et inassouvissable. Tout au plus, à leur limite, un double crépuscule: crepusculum vesperinum qui n'est plus le jour et qui n'est pas encore la nuit; crepusculum matutinum qui n'est plus la nuit et n'est pas encore le jour. C'est par cette image saisissante, on le sait, que Luther définissait l'être de l'homme ».

Dans ce crépuscule matutinal, auquel Baudelaire consacra un poème, dans cette lumière transversale, rasante, où le ciel semble plus proche de la terre, tout signe devient sacramentum, c'est-à-dire signe d'une chose cachée. L'oméga du crépuscule vespéral ouvre la mémoire à l'anamnésis du crépuscule matutinal. Par l'interprétation du « signe caché », du sacramentum, l'herméneute récitera, mais en sens inverse, le voyage de l'incarnation de l'esprit dans la matière, semblable, je cite « à la Columna gloriae constituée de toutes les parcelles de Lumière remontant de l'infernum à la terre de lumière, la Terra lucida ».

Dans ce crépuscule matutinal, auquel Baudelaire consacra un poème, dans cette lumière transversale, rasante, où le ciel semble plus proche de la terre, tout signe devient sacramentum, c'est-à-dire signe d'une chose cachée. L'oméga du crépuscule vespéral ouvre la mémoire à l'anamnésis du crépuscule matutinal. Par l'interprétation du « signe caché », du sacramentum, l'herméneute récitera, mais en sens inverse, le voyage de l'incarnation de l'esprit dans la matière, semblable, je cite « à la Columna gloriae constituée de toutes les parcelles de Lumière remontant de l'infernum à la terre de lumière, la Terra lucida ».

Matutinale est la pensée de l'implication dont l'interprétation est semblable à une procession liturgique, à une trans-ascendance vers la nuit lumineuse des Symboles. Voir les signes du monde et le monde des signes à la lumière de l'Ange suppose cette conquête du « suprasensible concret » qui n'appartient ni au monde matériel ni au monde de l'abstraction, mais à la présence même, qui selon la formule Héraclite, traduite par Battistini, « ne voile point, ne dévoile point, mais fait signe ». Or, si tout signe est signe d'éternité, la chance prodigieuse nous est offerte de lire les œuvres non plus au passé, comme s'y emploient les historiographies profanes et les fondamentalismes, mais bien au présent, à la lumière matutinale de l'Ange de la présence, témoin céleste de l'avènement herméneutique qui, souligne Henry Corbin, « implique justement la rupture avec le collectif, le rejonction avec la dimension transcendante qui prémunit individuellement la personne contre les sollicitations du collectif, c'est-à-dire contre toute socialisation du spirituel ».

L'implication de l'herméneute dans le déchiffrement des signes, le monde lui-même apparaissant, selon l'expression de Hugues de Saint-Victor, comme « la grammaire de Dieu », dévoile ainsi la vérité matutinale de l'Orient, en tant que « pôle de l'être », centre métaphysique, d'où l'Archange Logos nous invite à la transfiguration de l'entendement, à la conquête d'une surconscience délivrée des logiques grégaires, des infantilismes et des bestialités de ce que Simone Weil, après Platon, nomma « le Gros Animal », autrement dit, le monde social réduit à lui-même. « Le jour de la conscience, écrit Henry Corbin, forme un entre-deux entre la nuit lumineuse de la surconscience et la nuit ténébreuse de l'inconscience ». La psychologie transcendantale, dont Novalis, dans son Encyclopédie, déplorait l'inexistence ou la disparition, Henry Corbin en retrouvera non seulement les traces, mais la connaissance admirablement déployée dans la « Science de la Balance » et les théories chromatiques des soufis qui décrivent exactement l'espace versicolore entre la nuit ténébreuse et la nuit lumineuse, entre l'inconscience et la surconscience. L'intérêt de l'étude de cette psychologie transcendantale dépasse, et de fort loin, l'histoire des idées; elle se laisse si peu lire au passé, elle devance si largement nos actuels savoirs psychologiques que l'on doit imputer sans doute à une déplorable imperméabilité des disciplines qu'elle n'eût point encore renouvelé de fond en comble ces « sciences humaines » qui se revendiquent aujourd'hui de la psychologie ou de la psychanalyse, et semblent encore tributaires, à maint égards, du positivisme du dix-neuvième siècle.

Sans doute le moment est-il venu de ressaisir aussi l'œuvre de Henry Corbin dans cette vertu transdisciplinaire, qui fut d'ailleurs de tous temps le propre de toutes les grandes œuvres philosophiques, à commencer par celle de Sohravardî qui, dans son traité de la Sagesse orientale, résume toutes les sciences de son temps, à l'intersection des sagesses grecques, abrahamiques, zoroastriennes et védantiques.

Sans doute le moment est-il venu de ressaisir aussi l'œuvre de Henry Corbin dans cette vertu transdisciplinaire, qui fut d'ailleurs de tous temps le propre de toutes les grandes œuvres philosophiques, à commencer par celle de Sohravardî qui, dans son traité de la Sagesse orientale, résume toutes les sciences de son temps, à l'intersection des sagesses grecques, abrahamiques, zoroastriennes et védantiques.

De l'herméneutique heideggérienne, dont il fut un des premiers traducteur, jusqu'à cette phénoménologie de l'Esprit gnostique, que sont les magistrales études sur l'imagination créatrice dans le soufisme d'Ibn’Arabî, Henry Corbin renoue avec la lignée des philosophes qui ne limitent point leur dessein à méditer sur l'essence ou la légitimité de la philosophie, mais œuvrent, à l'exemple de Leibniz ou de Pascal, à partir d'un savoir, d'un corpus de connaissances, qu'ils portent au jour et qui, sans eux fût demeuré voilé, méconnu ou hors d'atteinte. L'acheminement, à travers les disciplines diverses qu'il éclaire, rétablit l'usage d'une gnose polyglotte et transdisciplinaire qui s'affranchit des assignations ordinaires du spécialiste. Au voyage extérieur, historique et géographique, correspond un voyage intérieur vers la Jérusalem Céleste, pour autant que ces deux personnage: le Chevalier de la célèbre gravure de Dürer, chère à Gilbert Durand, qui s'achemine vers le Jérusalem Céleste, entre la Mort et le Diable, et Ulysse sont les deux versants, l'un grec et l'autre abrahamique, de l'aventure herméneutique.

Mais revenons, faisons retour sur le principe même de l'acheminement, à partir d'une phrase lumineuse d'Eugenio d'Ors qui écrivait, je cite « Tout ce qui n'est pas tradition est plagiat ». L'herméneute participe de la tradition en ce qu'il suppose possible la traduction, en ce qu'il ne croit point en la nature arbitraire, immanente et close des langues humaines. Traduire, suppose à l'évidence, que l'on ne récuse point l'existence du Sens. Hamann, dans sa Rhapsodie en prose Kabbalistique, éclaire le processus herméneutique même de la traduction: « Parler, c'est traduire d'une langue angélique en une langue humaine, c'est-à-dire des pensées en des mots, des choses en des noms, des images en des signes ». Ce qui, dans les œuvres se donne à traduire est déjà, à l'origine, la traduction d'une langue angélique. L'office du traducteur-herméneute consistera alors à faire, selon la formule phénoménologique, « acte de présence » à ce dont le texte qu'il se propose de traduire est lui-même la traduction. Les théologiens médiévaux nommaient cette « présence » en amont, la vox cordis, la voix du cœur.

Loin de délaisser l'herméneutique heideggérienne et la phénoménologie occidentale, Henry Corbin en accomplit ainsi les possibles en de nouvelles palingénésies. A lire « au présent » les œuvres du passé, l'herméneute révèle le futur voilé inaccompli dans « l'Ayant-été ». « L'être-là, le dasein, écrit Henry Corbin, c'est essentiellement faire acte de présence, acte de cette présence par laquelle et pour laquelle se dévoile le sens au présent, cette présence sans laquelle quelque chose comme un sens au présent ne serait jamais dévoilé. La modalité de cette présence est bien alors d'être révélante, mais de telle sorte qu'en révélant le sens, c'est elle-même qui se révèle, elle-même qui est révélée ». L'implication essentielle de cette lecture au présent, qui révèle ce que le passé recèle d'avenir, fonde, nous dit Corbin, « le lien indissoluble, entre modi intellegendi et modi essendi, entre modes de comprendre et modes d'être ». Le dévoilement de ce qui est caché, c'est-à-dire de la vérité du Sens n'est possible que par cet acte de présence herméneutique qui, selon la formule soufie « reconduit la chose à sa source, à son archétype ». « Cet acte de présence, nous dit Henry Corbin, consiste à ouvrir, à faire éclore l'avenir que recèle le soi-disant passé dépassé. C'est le voir en avant de soi. ». A cet égard l'œuvre de Henry Corbin, bien plus que celle de Sartre ou de Derrida, qui usèrent à leur façon des approches de Sein und Zeit, semble véritablement répondre à la mise-en-demeure de la question heideggérienne, voire à la dépasser dans l'élan de son mouvement même.

Loin de délaisser l'herméneutique heideggérienne et la phénoménologie occidentale, Henry Corbin en accomplit ainsi les possibles en de nouvelles palingénésies. A lire « au présent » les œuvres du passé, l'herméneute révèle le futur voilé inaccompli dans « l'Ayant-été ». « L'être-là, le dasein, écrit Henry Corbin, c'est essentiellement faire acte de présence, acte de cette présence par laquelle et pour laquelle se dévoile le sens au présent, cette présence sans laquelle quelque chose comme un sens au présent ne serait jamais dévoilé. La modalité de cette présence est bien alors d'être révélante, mais de telle sorte qu'en révélant le sens, c'est elle-même qui se révèle, elle-même qui est révélée ». L'implication essentielle de cette lecture au présent, qui révèle ce que le passé recèle d'avenir, fonde, nous dit Corbin, « le lien indissoluble, entre modi intellegendi et modi essendi, entre modes de comprendre et modes d'être ». Le dévoilement de ce qui est caché, c'est-à-dire de la vérité du Sens n'est possible que par cet acte de présence herméneutique qui, selon la formule soufie « reconduit la chose à sa source, à son archétype ». « Cet acte de présence, nous dit Henry Corbin, consiste à ouvrir, à faire éclore l'avenir que recèle le soi-disant passé dépassé. C'est le voir en avant de soi. ». A cet égard l'œuvre de Henry Corbin, bien plus que celle de Sartre ou de Derrida, qui usèrent à leur façon des approches de Sein und Zeit, semble véritablement répondre à la mise-en-demeure de la question heideggérienne, voire à la dépasser dans l'élan de son mouvement même.

Ainsi de la notion fondamentale d'historialité (qu'Heidegger distingue de l'historicité en laquelle nous nous laissons insérer, nous interdisant par là même l'acte de présence phénoménologique) que Henry Corbin couronnera de la notion de hiéro-histoire: « histoire sacrale, laquelle ne vise nullement les fait extérieurs d'une "histoire sainte", d'une histoire du salut mais quelque chose de plus originel, à savoir l'ésotérique caché sous le phénomène de l'apparence littérale, celle des récits des Livres saints. » Si l'historialité permet de se déprendre des sommaires logiques déterministes, « en nous arrachant à l'historicité de l'Histoire », aux logiques purement discursives et chronologiques qui enferment les pensées dans leurs « contextes » sociologiques, la hiéro-histoire, elle, « nous apprend qu'il y a des filiations plus essentielles et plus vraies que les filiations historiques. » Non seulement les disparités linguistiques ou sociologiques ne nous interdisent pas de comprendre les œuvres du passé, mais, nous détachant des contingences de la chose dite, des écorces mortes, elles révèlent la vox cordis, la présence en acte, la vérité des filiations essentielles. L'empreinte visible détient le secret du sceau invisible et « la vieille image héraldique qui parlait en figures » dont parle Ernst Jünger dans La Visite à Godenholm, se révèle sous l'acception acquise des mots à celui interroge leur étymologie. Hamann, dans sa lumineuse « Rhapsodie » ne dit rien d'autre: « La poésie est la langue maternelle de l'humanité », de même que les alchimistes et des théosophes de l'Occident, les philosophes de la nature, les paracelsiens qui s'acheminent vers le déchiffrement des « signatures » de l'Invisible dans le visible et perçoivent la lumière révélante dans les éclats de la lumière révélée.

Le propre de cette langue, « qui parle en image », de cette langue prophétique et poétique sera, en dévoilant ce qui est caché, en laissant éclore et fleurir la lumière révélante, en élevant l'œcuménisme des branches et des racines jusqu'à la temporalité subtile de l'œcuménisme des essences et des parfums, de nous délivrer de la causalité historique, de transfigurer notre entendement, de l'ouvrir en corolle aux « Lumières seigneuriales » dont les lumières visibles et sensibles ne sont que les épiphénomènes ou les ombres. Lux umbra dei, disent les théologiens médiévaux: « La lumière est l'ombre de Dieu ». L'histoire n'est que l'ombre projetée dans les apparences de la hiéro-histoire. D'où, chez le gnostique, comme chez l'herméneute-phénoménologue, le nécessaire renversement de la métaphore.

Ce ne sont point l'Idée ou le Symbole qui sont métaphores de la nature ou de l'histoire, mais la nature et l'histoire qui sont une métaphore de l'Idée ou du Symbole. Ainsi, les interprétations allégoriques ou evhéméristes tombent d'elles-mêmes. Ce ne sont point les Symboles qui empruntent à la nature, ni les Mythes qui empruntent à l'histoire mais la nature et l'histoire qui en sont les reflets ou les réverbérations. Etre présent aux êtres et aux choses, c'est percevoir en eux l'éclat de la souveraineté divine dont ils procèdent. Le renversement de la métaphore dépasse la connaissance formelle, qui présume une représentation, pour atteindre à ce que les Ishrâqîyûns, les platoniciens de Perse, nomment une « connaissance présentielle ». Dès lors, les êtres et les choses ne sont plus des objets mais des présences. A « l'être pour la mort », qui fut pour un certain existentialisme, l'horizon indépassable de la pensée heideggérienne, et à la « laïcisation du Verbe » qui lui correspond (avec toutes les abusives et monstrueuses sacralisations de l'immanence qui s'ensuivirent), Henry Corbin répond par « l'être par-delà la mort » que dévoile « l'ek-stasis herméneutique » vers, je cite « ces autres mondes invisibles qui donnent son sens vrai au nôtre, à notre phénomène du monde. » Loin de débuter avec Sein und Zeit, comme sembleraient presque le croire quelques fondamentalistes heideggériens, la distinction classique entre l'Etre et l'étant (fut-il « Etant Suprême ») est précisément à l'origine de la méditation sur le tawhîd, sur « l'Attestation de l'Unique », qui est au cœur de la pensée d'Ibn’Arabî et de Sohravardî. Tout l'effort de ces gnostiques consiste à nous donner penser la distinction entre l'Unité théologique, exotérique, en tant que Ens supremum et l'Unificence ésotérique qui témoigne d'une ontologie de l'unité transcendantale de l'Etre. Nulle trace, ici, d'un « quiproquo onto-théologique », nul syncrétisme ou mélange malvenu. Pour reprendre la distinction platonicienne, la « doxa » ne confond pas avec la « gnosis ». Si la croyance s'adresse à un Dieu personnel ou à un Etant suprême, la gnose s'ordonne à la phrase ultime et oblative de Hallâj: « Le bon compte de l'Unique est que l'Unique le fasse unique », autrement dit, en langage eckhartien: « Le regard par lequel je vois Dieu et le regard par lequel Dieu me voit sont un seul et même regard. »

La Tradition, au sens d'art herméneutique de la traduction, Sapience de la « réelle présence », comme eût dit Georges Steiner, implication du « comprendre » dans l'être, est donc bien comme le suggère Eugenio d'Ors, recommencement, c'est-à-dire le contraire du plagiat ou du psittacisme. Ce qui est traduit recouvre son sens dans la traduction. Lorsque la traduction se prolonge en herméneutique, cette recouvrance est révélation. De même que les textes grecs nous sont parvenus par l'ambassade de la langue arabe, la traduction en français des textes persans et arabe de Sohravardî s'offre à nous comme un recommencement, une recouvrance, de la pensée grecque, aristotélicienne et platonicienne. L'œuvre de Henry Corbin s'inscrit ainsi dans une tradition et son art diplomatique, sinon par des circonstances contingentes, ne diffère pas essentiellement, des commentaires de ses prédécesseurs iraniens. Dans son mouvement odysséen, l'herméneutique, fut-elle le « commentaire d'un commentaire », ne s'éloigne point de la source du sens, mais s'en rapproche. Ainsi qu'Heidegger le disait à propos d'Hölderlin, certaines œuvres demeurent « en réserve »; et c'est bien à partir de cette « réserve », qui est le fret du navigateur, que s'accomplissent les renaissances, y compris artistiques. Point de Renaissance florentine, par exemple, sans le retour au texte, sans la volte néoplatonicienne de Pic de la Mirandole, de Marsile Ficin, ou celle kabbalistique et hébraïsante, du Cardinal Egide de Viterbe. La cause est entendue, ou devrait l'être depuis Saint-Bernard: « Nous sommes des nains assis sur les épaules des géants ». Non seulement les textes anciens ne nous sont pas devenus étrangers, incompréhensibles, inutiles, comme nous le veulent faire croire ces plagiaires qui s'intitulent parfois « progressistes », mais nos ombres qui nous devancent ne bougent que par la clarté antérieure qu'ils jettent sur nous. Traducteur, homme de Tradition, au sens étymologique, l'herméneute, ravive un lignage spirituel dont l'ultime manifestation, aussi obscurcie et profanée qu'elle soit, récapitule, pour qui sait se rendre attentif, l'entière lignée dont elle est l'aboutissement mais non la fin.

Les ultimes sections d'En Islam iranien portent ainsi sur la notion de chevalerie spirituelle et de lignage spirituel. Ce lignage toutefois n'implique nulle archéolâtrie, nulle vénération fallacieuse des « origines ». Il n'est point tourné vers le passé, et sa redite, il n'est récapitulation morne ou cortège funèbre, mais renouvellement du Sens, fine pointe phénoménologique obéissant à l'impératif grec: sôzeïn ta phaïmomenon, sauver les phénomènes. « Ce qu'une philosophie comparée doit atteindre, écrit Henry Corbin, dans les différents secteurs d'un champ de comparaison défini, c'est avant tout ce que l'on appelle en allemand Wesenschau, la perception intuitive d'une essence ». Or cette perception intuitive dépend, non plus d'une nostalgie mais d'une attente eschatologique qui, nous dit Corbin « est enracinée au plus profond de nos consciences ». L'archéon de l'archéologie, ne suffit pas à la reconquête de l'eschaton de l'eschatologie. La transmutation du temps du ressouvenir en temps du pressentiment suppose que nous surmontions « la grande infirmité de la pensée moderne » qui est l'emprisonnement dans l'Histoire et que nous retrouvions l'accès à notre temps propre. « Un philosophe, écrit Henry Corbin, est d'abord lui-même son temps propre car s'il est vraiment un philosophe, il domine ce qu'il est abusivement convenu d'appeler son temps, alors que ce temps n'est pas du tout le sien, puisqu'il est le temps anonyme de tout le monde. »

Les ultimes sections d'En Islam iranien portent ainsi sur la notion de chevalerie spirituelle et de lignage spirituel. Ce lignage toutefois n'implique nulle archéolâtrie, nulle vénération fallacieuse des « origines ». Il n'est point tourné vers le passé, et sa redite, il n'est récapitulation morne ou cortège funèbre, mais renouvellement du Sens, fine pointe phénoménologique obéissant à l'impératif grec: sôzeïn ta phaïmomenon, sauver les phénomènes. « Ce qu'une philosophie comparée doit atteindre, écrit Henry Corbin, dans les différents secteurs d'un champ de comparaison défini, c'est avant tout ce que l'on appelle en allemand Wesenschau, la perception intuitive d'une essence ». Or cette perception intuitive dépend, non plus d'une nostalgie mais d'une attente eschatologique qui, nous dit Corbin « est enracinée au plus profond de nos consciences ». L'archéon de l'archéologie, ne suffit pas à la reconquête de l'eschaton de l'eschatologie. La transmutation du temps du ressouvenir en temps du pressentiment suppose que nous surmontions « la grande infirmité de la pensée moderne » qui est l'emprisonnement dans l'Histoire et que nous retrouvions l'accès à notre temps propre. « Un philosophe, écrit Henry Corbin, est d'abord lui-même son temps propre car s'il est vraiment un philosophe, il domine ce qu'il est abusivement convenu d'appeler son temps, alors que ce temps n'est pas du tout le sien, puisqu'il est le temps anonyme de tout le monde. »

A se délivrer du temps anonyme, autrement dit de la temporalité grégaire, propre au « Gros Animal », l'herméneute, je cite, « s'insurge contre la prétention de réduire la notion d'événement aux événements de ce monde, perceptibles par la voie empirique, constatables par tout un chacun, enregistrés dans les archives. » A cette conception de l'homme à l'intérieur de l'histoire, s'opposera, écrit Henry Corbin « une conception fondamentale, sans laquelle celle de l'histoire extérieure est privée de tout fondement. Elle considère que c'est l'histoire qui est dans l'homme ». Ces événements intérieurs, supra historiques, sans lesquels il n'y aurait point d'événements extérieurs, ces visions, intuitions ou extases qui nous font passer du monde des phénomènes à celui des noumènes sont à la fois le fruit de la grâce et d'une décision résolue. Dans sa temporalité propre reconquise Ruzbéhân de Shîraz écrit: « Il m'arriva quelque chose de semblable aux lueurs du ressouvenir et aux brusques aperçus qui s'ouvrent à la méditation. »

Ce quelque chose qui arrive, ou, plus exactement qui advient, qui n'appartient ni à la subjectivité ni à la perception empirique, n'arrive toutefois pas à n'importe qui et ne peut être jugée, ou contredit par n'importe qui. Ce que voient les yeux de feu ne saurait être contesté par les yeux de chair. « Que valent en effet, écrit Henry Corbin, les critiques adressées à ceux qui ont vus eux-mêmes, donc aux témoins oculaires, par ceux qui n'ont jamais vu et ne verront jamais rien ? La position est intrépide, je le sais, mais je crois que la situation de nos jours est telle que le philosophe, conscient de sa responsabilité, doit faire sienne cette intrépidité sohravardienne. » L'événement intérieur porte en lui le principe de la recouvrance d'une temporalité délivrée des normes profanes et de ces formes de socialisation extrême où se fourvoient les fondamentalismes religieux ou profanes. Ces événements hiérologiques dévoilent à l'intrépide, c'est-à-dire au chevalier spirituel, ce qui caché dans ce qui se révèle en frappant d'inconsistance le hiatus chronologique qui nous en sépare. Ce caché-révélé, qui réconcilie Héraclite et Platon, nous indique que l'Idée est à la fois immanente et transcendante. Elle est immanente, par les formes perceptibles qu'elle donne aux choses mais transcendante car, selon la belle formule platonisante d'André Fraigneau, « sans jeunesse antérieure et sans vieillesse possible ».

Ce paradoxe, que la philosophe platonicienne résout sous le terme de methexis, c'est-à-dire de « participation », précède un autre paradoxe. Les Platoniciens de Perse parlent en effet des Idées comme de natures ou de substances « missionnées » ou « envoyées ». Cet impérissable que sont les Idées n'est point figé dans un ciel immuable, mais nous est envoyé dans une perspective eschatologique, dans la profondeur du temps qui doit advenir. Dans le creuset de la pensée des Platoniciens de Perse, la fusion des Idées platoniciennes, des archanges zoroastriens, des Puissances divines (Dynameis) de Philon d'Alexandrie s'accomplit bien dans et par un feu prophétique. Les Lumières des Idées archétypes, comparables aux séphiroth de la kabbale hébraïque, ne demeurent point dans leur lointain: elles ont pour mission de nous faire advenir au saisissement de leur splendeur, elles nous sont « envoyées » pour que nous puissions établir un pont entre l'archéon et l'eschaton, entre ce que nous dévoile l'anamnésis et ce qui demeure caché dans les fins dernières. La Tradition à laquelle se réfère la chevalerie spirituelle n'a d'autre sens: elle est cette tension, dans la présence même de l'expérience intérieure, d'une relation entre ce qui n'est plus et ce qui n'est pas encore. Cette Tradition n'est point commémorative ou muséologique mais éveil du plus lointain dans la présence, fraîcheur castalienne, élévation verdoyante du Sens, semblable à l'Arbre qui, dans l'Ile Verte domine le temple de l'Imâm Caché.

Ce paradoxe, que la philosophe platonicienne résout sous le terme de methexis, c'est-à-dire de « participation », précède un autre paradoxe. Les Platoniciens de Perse parlent en effet des Idées comme de natures ou de substances « missionnées » ou « envoyées ». Cet impérissable que sont les Idées n'est point figé dans un ciel immuable, mais nous est envoyé dans une perspective eschatologique, dans la profondeur du temps qui doit advenir. Dans le creuset de la pensée des Platoniciens de Perse, la fusion des Idées platoniciennes, des archanges zoroastriens, des Puissances divines (Dynameis) de Philon d'Alexandrie s'accomplit bien dans et par un feu prophétique. Les Lumières des Idées archétypes, comparables aux séphiroth de la kabbale hébraïque, ne demeurent point dans leur lointain: elles ont pour mission de nous faire advenir au saisissement de leur splendeur, elles nous sont « envoyées » pour que nous puissions établir un pont entre l'archéon et l'eschaton, entre ce que nous dévoile l'anamnésis et ce qui demeure caché dans les fins dernières. La Tradition à laquelle se réfère la chevalerie spirituelle n'a d'autre sens: elle est cette tension, dans la présence même de l'expérience intérieure, d'une relation entre ce qui n'est plus et ce qui n'est pas encore. Cette Tradition n'est point commémorative ou muséologique mais éveil du plus lointain dans la présence, fraîcheur castalienne, élévation verdoyante du Sens, semblable à l'Arbre qui, dans l'Ile Verte domine le temple de l'Imâm Caché.

L'intrépidité sohravardienne qu'évoque Henry Corbin et qu'il fit sienne, cette vertu d'areté, qui est à la fois homérique et évangélique, donne seule accès à ce qu’il nomme, à partir de l'œuvre de Mollâ Sadrâ, « la métaphysique existentielle » des palingénésies et des métamorphoses que supposent le processus initiatique et la tension eschatologique: « L'acte d'exister, écrit Henry Corbin est en effet capable d'une multitude de degrés d'intensification ou de dégradation. Pour la métaphysique des essences, le statut de l'homme, par exemple, ou le statut du corps sont constant. Pour la métaphysique existentielle de Mollâ Sadrâ, être homme comporte une multitude de degrés, depuis celui des démons à face humaine jusqu'à l'état sublime de l'Homme Parfait. Ce qu'on appelle le corps passe par une multitude d'états, depuis celui du corps périssable de ce monde jusqu'à l'état du corps subtil, voire du corps divin. Chaque fois ces exaltations dépendent de l'intensification ou de l'atténuation, de la dégradation de l'existence, de l'acte d'exister ». Ce champ de variation, cette « latitude des formes » est au principe même de l'expérience intérieure, des événements du monde imaginal. Leur histoire est l'histoire sacrée de la temporalité propre du chevalier spirituel, le signe de son intrépidité à reconnaître dans les apparences la figure héraldique dont elles procèdent par la précision des lignes et l'intensité des couleurs. L'herméneutique tient ainsi à une métaphysique de l'attention et de l'intensité. La tension de l'attente eschatologique favorise l'intensité de l'attention. A l'opposé de cette tension, l'inattention à autrui, au monde et à soi-même est atténuation et dégradation de l'acte d'exister, par le mépris, l'indifférence, l'insensibilité, la complaisance dans l'illusion ou l'erreur, la vénération du confus ou de l'informe, qui engendrent les pires conformismes.

L'areté de l'herméneute, l'intrépidité chevaleresque précisent ainsi une éthique, c'est-à-dire une notion du Bien, indissociable du Vrai et du Beau qui s'exerce par l'attente et l'attention, en nous faisant hôtes, au double sens du mot: recevoir et être reçu. Si le voyage chevaleresque entre l'Orient et l'Occident définit une géographie sacrée avec ses épicentres, ses sites de haute intensité spirituelle, ses « cités emblématiques » où la Vision advint, où s'opéra la jonction entre le sensible et l'Intelligible, c'est bien parce qu'il se situe dans l'attente et dans l'attention, dans l'accroissement de la latitude des formes, et non dans la soumission aux opinions, aux jugements collectifs, fussent-ils de prétention religieuse. Que des temples eussent été édifiés à l'endroit où des errants, des déracinés, ont vu la terre et le Ciel s'accorder, que, de la sorte, l'espace et la géographie sacrée fussent déterminés par les révélations, les extases des « Nobles Voyageurs », cela suffirait à montrer que le mouvement, le tradere, la pérégrination précède les certitudes établies. D'où l'importance de la distinction, maintes fois réaffirmée par Henry Corbin et les auteurs dont il traite, entre la vérité ésotérique, intérieure, et l'exotérisme dominateur, qui veut emprisonner la spéculation et la vision dans l'immobilité d'une légalité outrecuidante et ratiocinante.

L'areté de l'herméneute, l'intrépidité chevaleresque précisent ainsi une éthique, c'est-à-dire une notion du Bien, indissociable du Vrai et du Beau qui s'exerce par l'attente et l'attention, en nous faisant hôtes, au double sens du mot: recevoir et être reçu. Si le voyage chevaleresque entre l'Orient et l'Occident définit une géographie sacrée avec ses épicentres, ses sites de haute intensité spirituelle, ses « cités emblématiques » où la Vision advint, où s'opéra la jonction entre le sensible et l'Intelligible, c'est bien parce qu'il se situe dans l'attente et dans l'attention, dans l'accroissement de la latitude des formes, et non dans la soumission aux opinions, aux jugements collectifs, fussent-ils de prétention religieuse. Que des temples eussent été édifiés à l'endroit où des errants, des déracinés, ont vu la terre et le Ciel s'accorder, que, de la sorte, l'espace et la géographie sacrée fussent déterminés par les révélations, les extases des « Nobles Voyageurs », cela suffirait à montrer que le mouvement, le tradere, la pérégrination précède les certitudes établies. D'où l'importance de la distinction, maintes fois réaffirmée par Henry Corbin et les auteurs dont il traite, entre la vérité ésotérique, intérieure, et l'exotérisme dominateur, qui veut emprisonner la spéculation et la vision dans l'immobilité d'une légalité outrecuidante et ratiocinante.

Ainsi, la notion de chevalerie spirituelle, que Henry Corbin définit comme un compagnonnage avec l'Ange, se donne à comprendre comme l'acheminement de la philosophie vers la métaphysique, c'est-à-dire vers son origine, sa source désempierrée. Loin d'être une philosophie plus abstraite que la philosophie, la métaphysique de la « latitude des formes » se distingue, comme le souligne Jean Brun par une relation concrète à des hommes concrets: « L'homme qui prétend atteindre une connaissance directe de Dieu par la nature ou par l'histoire se divinise et ne rend, en effet, témoignage que de lui-même. » Si la philosophie forge la clavis herméneutica, la métaphysique ouvre la porte qui nous porte au-delà du seuil. « Un mot simple comme l'être, écrit Jünger, a des profondeurs plus grandes qu'on ne saurait l'exprimer, ni même le penser. Par un mot comme sésame, l'un entend une poignée de graines oléagineuses, alors que l'autre, en le prononçant, ouvre d'un coup la porte d'une caverne aux trésors. Celui-ci possède la clef. Il a dérobé au pivert le secret de faire s'ouvrir la balsamine. » La clef n'est point la porte et la porte n'est point l'espace inconnu qu'elle ouvre à celui qui la franchit. Toutefois, ainsi que le souligne Jünger, « ce sont les grandes transitions que l'on remarque le moins. »

On ne saurait ainsi nier, que, par la vertu de l'art odysséen de l'herméneutique, une sorte de translation essentielle soit possible entre la philosophie et la métaphysique. Si la vérité ne se réduit pas à la cohérence des propositions logiques, si elle est bien aléthéia, dévoilement et ressouvenir, c'est-à-dire expérience intérieure où l'homme en tant qu'être du lointain s'éveille à la « coprésence », la conversion du regard qui change la philosophie en métaphysique, les yeux de chair en yeux de feu, échappe à toute contrôle, à toute vérification, voire à toute législation. De ce voyage intérieur, le grand soufi Djalal-ûd-din Rûmi put dire: « Ceci n'est pas l'ascension de l'homme jusqu'à la lune mais l'ascension de la canne à sucre jusqu'au sucre. » Le savoir ne devient Sapience, la philosophie ne devient métaphysique que par l'épreuve de la saveur, de l'essentielle intimité du voyage intérieur. S'adressant à nous, c'est-à-dire à ces êtres du lointain que nous étions pour lui, dans la coprésence du ressouvenir et de l'attente, Sohravardî nous dit « Toi-même tu es l'un des bruissements des ailes de Gabriel ». L'embarcation herméneutique est la clef de la mer et du ciel, le vaisseau subtil alchimique de l'interprétation infinie nous invite au dialogue où la lumière matérielle, sensible, devient la lux perpétua de la philosophie illuminative, autrement dit de la métaphysique. Ce que le ciel et la mer ont à se dire, en assombrissements et en splendeurs, nous invite à nous retrouver nous- mêmes. « Nous sommes un dialogue, écrit Heidegger, dans ses Approches de Hölderlin, l'unité du dialogue consiste en ce que chaque fois, dans la parole essentielle soit révélé l'Un et même sur lequel nous nous unissons, en raison duquel nous sommes Un et ainsi authentiquement nous -mêmes. » Loin de ramener le religieux au social, ou la philosophie à une religiosité grégaire, la conversion de la philosophie en métaphysique, telle qu'elle s'illustre dans l'œuvre de Henry Corbin, en ce voyage vers l'Ile Verte en la mer blanche nous conduit à une science de la vérité cachée, non détenue, et, par voie de conséquence, rétive à toute instrumentalisation.

Ces dernières décennies nous ont montré, si nécessaire, que l'instrumentalisation du religieux en farces sanglantes appartenait bien à notre temps, qu'elle était, selon la formule de René Guénon, avec la haine du secret, un des « Signes des Temps » qui sont les nôtres. Si elle n'est pas cortège funèbre, fixation sur la lettre morte, idolâtrie des écorces de cendre, la Tradition est renaissance, recueillement dans la présence du voyage intérieur où l'Un dans son unificence devient principe d'universalité. « Il ne s'agit plus, écrit Jean Brun, de permettre à l'historicisme d'accomplir son travail dissolvant en laissant croire que la recherche des sources se situe dans le cadre d'une histoire comparée de la philosophie des religions ou de la mythologie. Toutes ces spécialités analysent des combustibles ou des cendres au lieu de se laisser illuminer par le feu de la Tradition. » Il ne s'agit pas davantage, de se soumettre, par fidélité aveugle, à des coutumes ou des dénomination confessionnelles, d'emprisonner la parole dans la catastrophe de répétition mais bien de comprendre la vertu paraclétique de la Tradition, qui n'est point un « mythe » au sens de mensonge, moins encore une réalité historique mais, selon la formule de Henry Corbin « un synchronisme réglant un champs de conscience dont les lignes de force nous montrent à l'œuvre les mêmes réalités métaphysiques. » Le Paraclet est la présence même dont l'advenue confirme en nous la pertinence de l'idée augustinienne selon laquelle le passé et le présent, par le souvenir et l'attente, sont présents dans la présence. « Tout se passe, écrit Henry Corbin, comme si une voix se faisait entendre à la façon dont se ferait entendre au grand orgue le thème d'une fugue, et qu'une autre voix lui donnât la réponse par l'inversion du thème. A celui qui peut percevoir les résonances, la première voix fera peut-être entendre le contrepoint qu'appelle la seconde, et d'épisode en épisode l'exposé de la fugue sera complet. Mais cet achèvement c'est le Mystère de la Pentecôte, et seul le Paraclet a mission de le dévoiler. »

Ces dernières décennies nous ont montré, si nécessaire, que l'instrumentalisation du religieux en farces sanglantes appartenait bien à notre temps, qu'elle était, selon la formule de René Guénon, avec la haine du secret, un des « Signes des Temps » qui sont les nôtres. Si elle n'est pas cortège funèbre, fixation sur la lettre morte, idolâtrie des écorces de cendre, la Tradition est renaissance, recueillement dans la présence du voyage intérieur où l'Un dans son unificence devient principe d'universalité. « Il ne s'agit plus, écrit Jean Brun, de permettre à l'historicisme d'accomplir son travail dissolvant en laissant croire que la recherche des sources se situe dans le cadre d'une histoire comparée de la philosophie des religions ou de la mythologie. Toutes ces spécialités analysent des combustibles ou des cendres au lieu de se laisser illuminer par le feu de la Tradition. » Il ne s'agit pas davantage, de se soumettre, par fidélité aveugle, à des coutumes ou des dénomination confessionnelles, d'emprisonner la parole dans la catastrophe de répétition mais bien de comprendre la vertu paraclétique de la Tradition, qui n'est point un « mythe » au sens de mensonge, moins encore une réalité historique mais, selon la formule de Henry Corbin « un synchronisme réglant un champs de conscience dont les lignes de force nous montrent à l'œuvre les mêmes réalités métaphysiques. » Le Paraclet est la présence même dont l'advenue confirme en nous la pertinence de l'idée augustinienne selon laquelle le passé et le présent, par le souvenir et l'attente, sont présents dans la présence. « Tout se passe, écrit Henry Corbin, comme si une voix se faisait entendre à la façon dont se ferait entendre au grand orgue le thème d'une fugue, et qu'une autre voix lui donnât la réponse par l'inversion du thème. A celui qui peut percevoir les résonances, la première voix fera peut-être entendre le contrepoint qu'appelle la seconde, et d'épisode en épisode l'exposé de la fugue sera complet. Mais cet achèvement c'est le Mystère de la Pentecôte, et seul le Paraclet a mission de le dévoiler. »

Loin de se réduire à un comparatisme profane, l'art de percevoir des résonances relève lui-même sinon du Mystère du moins d'une approche du Mystère. Husserl, qui définissait la phénoménologie comme une « communauté gnostique » disait que, pour mille étudiants capables de restituer ses cours de façon satisfaisante et même brillante, il ne devait s'en trouver que deux ou trois pour avoir vraiment réalisé en eux-mêmes l'expérience phénoménologique du « Nous transcendantal ». Sans doute en est-il de même des symboles religieux, qui peuvent être de banales représentations d'une appartenance collective ou pure présence d'un retour paraclétique à soi-même, c'est à dire au principe d'un au-delà de l'individualisme, d'une universalité métaphysique dont l'uniformisation moderne n'est que l'abominable parodie. « J'ai réfléchi, dit Hallâj, sur les dénominations confessionnelles, faisant effort pour les comprendre, et je les considère comme un Principe unique à ramification nombreuses. Ne demande donc pas à un homme d'adopter telle dénomination confessionnelle, car cela l'écarterait du Principe fondamental, et certes, c'est ce Principe Lui-même qui doit venir le chercher, Lui en qui s'élucident toutes les grandeurs et toutes les significations: et l'homme alors comprendra. »

Que le Principe dût nous venir chercher, car il est de l'ordre du ressouvenir et de l'attente, de la nostalgie et du pressentiment, que nous ne puissions-nous saisir de Lui, nous l'approprier, le soumettre à l'hybris de nos ambitions trop humaines, il suffit pour s'en persuader de comprendre ce qu'Heidegger disait du langage: « Le langage n'est pas un instrument disponible, il est tout au contraire, cet historial qui lui-même dispose de la suprême possibilité de l'être de l'homme. » L'apparition vespérale-matutinale de l'Archange Logos, dont nous ne sommes qu'un bruissement, ce dévoilement de la vérité hors d'atteinte, à la fois anamnésis et désir, n'est autre, selon la formule de Rûmi que « la recherche de la chose déjà trouvée » qui, entre la nuit et le jour, réinvente le dialogue de l'Unique avec l'unique: « Si tu te rapproches de moi, c'est parce que je me suis rapproché de toi. Je suis plus près de toi que toi-même, que ton âme, que ton souffle ».

Que le Principe dût nous venir chercher, car il est de l'ordre du ressouvenir et de l'attente, de la nostalgie et du pressentiment, que nous ne puissions-nous saisir de Lui, nous l'approprier, le soumettre à l'hybris de nos ambitions trop humaines, il suffit pour s'en persuader de comprendre ce qu'Heidegger disait du langage: « Le langage n'est pas un instrument disponible, il est tout au contraire, cet historial qui lui-même dispose de la suprême possibilité de l'être de l'homme. » L'apparition vespérale-matutinale de l'Archange Logos, dont nous ne sommes qu'un bruissement, ce dévoilement de la vérité hors d'atteinte, à la fois anamnésis et désir, n'est autre, selon la formule de Rûmi que « la recherche de la chose déjà trouvée » qui, entre la nuit et le jour, réinvente le dialogue de l'Unique avec l'unique: « Si tu te rapproches de moi, c'est parce que je me suis rapproché de toi. Je suis plus près de toi que toi-même, que ton âme, que ton souffle ».

Loin d'être cet Etant suprême de la théologie exotérique, qui nous tient en exil de la vérité de l'être, séparé de l'éclaircie essentielle, Dieu est alors celui qui se voit lui-même à travers nous-mêmes, de même que nous ne parlons pas le langage mais que le langage se parle à travers nous, nous disant, par exemple, par la bouche d'Ibn’Arabî, à ce titre prédécesseur de la Mystique rhénane,: « C'est par mon œil que tu me vois , ce n'est pas par ton œil que tu peux me concevoir ». Croire que Dieu n'est qu'un Etant suprême, c'est confondre la forme avec ce qu'elle manifeste, c'est être idolâtre, c'est demeurer sourd à l'Appel, c'est renoncer à la vision du cœur et à l'attestation de l'Unique. A la tristesse, la morosité, l'ennui, la jalousie, le ressentiment qui envahissent l'âme emprisonnée dans l'exil occidental, dans le ressassement du déclin, dans l'oubli de l'oubli comme dans « la volonté de la volonté », la vertu paraclétique oppose la ferveur, la légèreté dansante, le tournoiement des possibles, l'intensification des actes d'exister. « Comment, écrit Rûmi, le soufi pourrait-il ne pas se mettre à danser, tournoyant sur lui-même comme l'atome au soleil de l'éternité afin qu'il le délivre de ce monde périssable ? » S'unissant en un même mouvement, dans un même tournoiement des possibles, la nostalgie et le pressentiment, le passé et le futur se délivrent d'eux-mêmes pour éclore dans la présence pure en corolle, qui est la réponse même, le répons, à « la question qui ne vient ni du monde, ni de l'homme ».

La clef herméneutique heideggérienne, trouvant son usage pertinent dans la métaphysique, qui n'est plus la métaphysique dualiste, et pour tout dire caricaturale, du platonisme scolaire, ni la théologie de l'Etant suprême, ni la soumission aveugle à la forme en tant que telle, - en nous ouvrant à la perspective de la « gradation infinie » des états de l'être et de la conscience, du plus atténué au plus intense, en graduant la connaissance selon les principes initiatiques, nous délivre ainsi, du même geste, de toute forme de socialisation extrême, de tout fondamentalisme, fût-il « démocratique ». L'Imâm caché sous le grand Arbre cosmogonique d'où jaillit la source la vie, l'eau castalienne de la mémoire retrouvée, interdit toute socialisation du religieux, toute réduction du Symbole à la part visible et immanente, à une beauté qui ne serait que purement terrestre, donc relative et variable selon les us et coutumes. La laideur qui s'empare des Symboles profanés, des coutumes instrumentalisées, est un signe de la fausseté qui en abuse. La Beauté prouve le Vrai, comme l'humilité et courtoisie prouvent le Bien. Si le monde sensible est la métaphore de l'intelligible, si la forme perçue est le miroir de la forme idéale, ce monde-ci, avec ses Normes profanes, ses communautés vindicatives, ne peut en aucune façon prétendre au Beau et au Vrai. « Dès que les hommes se rassemblent, écrit Henry de Montherlant, ils travaillent pour quelque erreur. Seule l'âme solitaire dialogue avec l'esprit de vérité. » Cette solitude cependant, par un paradoxe admirable, n'est point esseulement mais communion car elle suppose l'oubli de soi-même, l'extinction du moi devant l'Ange de la Face, le consentement à la pérégrination infinie loin de soi-même, dans les écumes de la mer blanche et le pressentiment de l'Ile Verte. Au relativisme absolu des Modernes, qui emprisonnent chaque chose dans une abstraction profane, pour lesquels « le corps n'est que le corps », la danse des soufis oppose l'absolu des relations tournoyantes dans l'approche d'une Beauté dont toutes les beautés relatives ne sont que l'émanation ou le reflet. A la philosophie, comme instrument de pouvoir (ce qu'elle fut, dans la continuité hégélienne, avec fureur) la métaphysique reconquise, par l'humilité et l'abandon à la grandeur divine, opposera ce décisif retournement de la métaphore qui laisse à la beauté de la vérité son resplendissement, comme le reflet du soleil sur la mer, comme la solitude de l'Unique pour un unique.

Luc-Olivier d'Algange.

L’œuvre de Dominique de Roux témoigne d’une stratégie de rupture, mais rupture pour retrouver la plénitude de l’être, à laquelle, selon la théologie apophatique, « tout ce qui s’ajoute retranche ». Il faut donc rompre là, s’arracher avec une ruse animale non moins qu’avec l’art de la guerre (et l’on sait l’intérêt tout particulier que Dominique de Roux porta à Sun Tsu et à Clausewitz) pour échapper à ce qui caractérise abusivement, à ce qui détermine, et semble ajouter à ce que nous sommes, alors que la plénitude est déjà là, dans « l’être-là », dans l’existant pur, lorsque celui-ci, par une succession d’épreuves initiatiques, de ressouvenirs orphiques, de victoires sur les hypnoses léthéennes, devient le témoin de l’être et l’hôte du Sacré.

L’œuvre de Dominique de Roux témoigne d’une stratégie de rupture, mais rupture pour retrouver la plénitude de l’être, à laquelle, selon la théologie apophatique, « tout ce qui s’ajoute retranche ». Il faut donc rompre là, s’arracher avec une ruse animale non moins qu’avec l’art de la guerre (et l’on sait l’intérêt tout particulier que Dominique de Roux porta à Sun Tsu et à Clausewitz) pour échapper à ce qui caractérise abusivement, à ce qui détermine, et semble ajouter à ce que nous sommes, alors que la plénitude est déjà là, dans « l’être-là », dans l’existant pur, lorsque celui-ci, par une succession d’épreuves initiatiques, de ressouvenirs orphiques, de victoires sur les hypnoses léthéennes, devient le témoin de l’être et l’hôte du Sacré.  L'exil, dans un monde déserté de l'être, dans un monde de vide et de vent, où toute présence réelle est démise par sa représentation dans une sorte de platonisme inversé, est notre plus profond enracinement. Et ce plus profond enracinement est ce qui nous projette, nous emporte au voisinage des prophéties. « Etre aristocrate, que voulez-vous, c’est ne jamais avoir coupé les ponts avec ailleurs, avec autre chose ». Cette fidélité aristocratique, qui scelle le secret de l’exil ontologique, autrement dit, de l’exil de l’être en lui-même, dans le cœur et dans l’âme de quelques uns, est au plus loin de la seule révérence au passé, aux coutumes d’une identité vouée aux processions funéraires : « Je ne me dédouble pas je cherche à multiplier l’existence, toujours dans le flot des fluctuations, vérités et mensonges qui existent, qui n’existent pas, au bord du langage. »

L'exil, dans un monde déserté de l'être, dans un monde de vide et de vent, où toute présence réelle est démise par sa représentation dans une sorte de platonisme inversé, est notre plus profond enracinement. Et ce plus profond enracinement est ce qui nous projette, nous emporte au voisinage des prophéties. « Etre aristocrate, que voulez-vous, c’est ne jamais avoir coupé les ponts avec ailleurs, avec autre chose ». Cette fidélité aristocratique, qui scelle le secret de l’exil ontologique, autrement dit, de l’exil de l’être en lui-même, dans le cœur et dans l’âme de quelques uns, est au plus loin de la seule révérence au passé, aux coutumes d’une identité vouée aux processions funéraires : « Je ne me dédouble pas je cherche à multiplier l’existence, toujours dans le flot des fluctuations, vérités et mensonges qui existent, qui n’existent pas, au bord du langage. » Ecrire sera ainsi pour Dominique de Roux cette action subversive, « ultra-moderne » qui consiste à retourner à l’intérieur des mots la parole contre les mots, à subvertir, donc, l’exotérique par l’ésotérique et à ne plus s’en laisser conter par ceux-là qui oublient que la parole humaine voyage entre les lèvres et les oreilles, comme sur les lignes ou entre les lignes, qu’elle voyage entre celui qui la formule et celui qui la reçoit, comme entre la vie et la mort, le visible et l’invisible : ce profond mystère qui se laisse sinon éclaircir, du moins comprendre, par la Théologie.

Ecrire sera ainsi pour Dominique de Roux cette action subversive, « ultra-moderne » qui consiste à retourner à l’intérieur des mots la parole contre les mots, à subvertir, donc, l’exotérique par l’ésotérique et à ne plus s’en laisser conter par ceux-là qui oublient que la parole humaine voyage entre les lèvres et les oreilles, comme sur les lignes ou entre les lignes, qu’elle voyage entre celui qui la formule et celui qui la reçoit, comme entre la vie et la mort, le visible et l’invisible : ce profond mystère qui se laisse sinon éclaircir, du moins comprendre, par la Théologie. Des temps où il fut notre aîné, Dominique de Roux nous incita à donner forme à notre dessein. Devenu notre cadet, lorsque nous eûmes dépassé la frontière des quarante-deux ans, son œuvre nous fut cette mise-en-demeure à ne point céder, à garder au cœur la juvénile curiosité, à déchiffrer, dans son écriture aux crêtes téméraires, le sens d’une jeunesse qui, suspendue trop tôt dans l’absence, ne peut finir. Il y a une écriture de Dominique de Roux, un style, un usage de la langue française en révolte contre cette facilité à glisser, avec élégance, mais sans conséquence, sur la surface du monde. On s’exténue à condamner ou à défendre sa plume de « polémiste d’extrême-droite », alors que ce qui advient dans ces bouillonnements, ces ébréchures, ces anfractuosités n’est autre que la pure poésie.

Des temps où il fut notre aîné, Dominique de Roux nous incita à donner forme à notre dessein. Devenu notre cadet, lorsque nous eûmes dépassé la frontière des quarante-deux ans, son œuvre nous fut cette mise-en-demeure à ne point céder, à garder au cœur la juvénile curiosité, à déchiffrer, dans son écriture aux crêtes téméraires, le sens d’une jeunesse qui, suspendue trop tôt dans l’absence, ne peut finir. Il y a une écriture de Dominique de Roux, un style, un usage de la langue française en révolte contre cette facilité à glisser, avec élégance, mais sans conséquence, sur la surface du monde. On s’exténue à condamner ou à défendre sa plume de « polémiste d’extrême-droite », alors que ce qui advient dans ces bouillonnements, ces ébréchures, ces anfractuosités n’est autre que la pure poésie. Rien n’importe que « la saison mystérieuse de l’âme». Toutes nos luttes, nos impatiences, et notre solitude conquise et notre exil, nos œuvres, qui ne sont ni des victoires ni des défaites, tout cela, non seulement au bout du compte, mais dès le départ ne vaut que pour ces retrouvailles légères : « Je viendrai en janvier. Je viendrai longtemps. Vous me parlerez encore des jardins et des hommes… dans cette petite salle blanche du monastère qui sent la pomme et le grain, sur cette colline de silence et de beauté, parmi les pluies qui tressent tout autour une saison mystérieuse. Je vous écouterai. Vous calmerez ma foi clignotante comme une étoile. J’enserrerai votre trésor comme un écureuil entre mes mains. »

Rien n’importe que « la saison mystérieuse de l’âme». Toutes nos luttes, nos impatiences, et notre solitude conquise et notre exil, nos œuvres, qui ne sont ni des victoires ni des défaites, tout cela, non seulement au bout du compte, mais dès le départ ne vaut que pour ces retrouvailles légères : « Je viendrai en janvier. Je viendrai longtemps. Vous me parlerez encore des jardins et des hommes… dans cette petite salle blanche du monastère qui sent la pomme et le grain, sur cette colline de silence et de beauté, parmi les pluies qui tressent tout autour une saison mystérieuse. Je vous écouterai. Vous calmerez ma foi clignotante comme une étoile. J’enserrerai votre trésor comme un écureuil entre mes mains. » A l’exigence morale qui consiste à ne pas être là où les autres vous attendent correspondra une écriture aux incidentes imprévisibles où les mots inattendus, dans leurs explosions fixes, captent les éclats du pur instant : « Par rapport à l’écriture, ni loi, ni science, pas même une destinée ». L’héritage comme force motrice, élan donné, s’oppose à la destinée, forme consentie de la soumission. Du peu de liberté qui nous reste, l’anti-moderne ultra-moderne veut étendre le champ d’action et les prestiges secrets pour aller vers la réalité, tracé de lumière entre deux ténèbres : « Retrouver la réalité, aller vers le réel, l’élémentaire, vers la mort prévue de l’homme et vers l’homme secret qui vit encore, vers sa réapparition dans la forme nouvelle, dans l’éternelle jeunesse de l’antiforme éternelle ».

A l’exigence morale qui consiste à ne pas être là où les autres vous attendent correspondra une écriture aux incidentes imprévisibles où les mots inattendus, dans leurs explosions fixes, captent les éclats du pur instant : « Par rapport à l’écriture, ni loi, ni science, pas même une destinée ». L’héritage comme force motrice, élan donné, s’oppose à la destinée, forme consentie de la soumission. Du peu de liberté qui nous reste, l’anti-moderne ultra-moderne veut étendre le champ d’action et les prestiges secrets pour aller vers la réalité, tracé de lumière entre deux ténèbres : « Retrouver la réalité, aller vers le réel, l’élémentaire, vers la mort prévue de l’homme et vers l’homme secret qui vit encore, vers sa réapparition dans la forme nouvelle, dans l’éternelle jeunesse de l’antiforme éternelle ».  « L’exil n’est pas une autre demeure. Il est séparation d’avec notre demeure. L’exil s’accompagne de la volonté de retour. C’est le visage dans les mains de l’homme séparé de lui-même (…) Et si la grande poésie arrache au monde, le développement de l’exil ne concerne pas seulement l’expérience de celui qui le vit, il abandonne les organisations têtes baissées vers la flamme et commence une vie nouvelle, cherchant la passe. »

« L’exil n’est pas une autre demeure. Il est séparation d’avec notre demeure. L’exil s’accompagne de la volonté de retour. C’est le visage dans les mains de l’homme séparé de lui-même (…) Et si la grande poésie arrache au monde, le développement de l’exil ne concerne pas seulement l’expérience de celui qui le vit, il abandonne les organisations têtes baissées vers la flamme et commence une vie nouvelle, cherchant la passe. » Le révolutionnaire comme le contre-révolutionnaire sont des nihilistes : ils nient la mémoire réelle, ils veulent, dans l’hybris de leur volonté, conformer le monde à leurs plans : hybris de ménagère et non de conquérant. Il faut défendre sa vision du monde ; mais telle est la limite du colonialisme, il convient que les mondes conquis, et même le monde natal, nous demeurent quelque peu étrangers. Cette étrangeté discrète et persistante est la condition universelle de l’homme que les planificateurs modernes ont en horreur et dont ils veulent à tout prix départir les êtres et les choses au nom d’un « universalisme » qui n’est rien d’autre que la plus odieuse des hégémonies, la soumission des temporalités subtiles de l’âme au temps utilitaire, au faux destin de l’Histoire idolâtrée, à l’optimisme stupide, au nihilisme béat.

Le révolutionnaire comme le contre-révolutionnaire sont des nihilistes : ils nient la mémoire réelle, ils veulent, dans l’hybris de leur volonté, conformer le monde à leurs plans : hybris de ménagère et non de conquérant. Il faut défendre sa vision du monde ; mais telle est la limite du colonialisme, il convient que les mondes conquis, et même le monde natal, nous demeurent quelque peu étrangers. Cette étrangeté discrète et persistante est la condition universelle de l’homme que les planificateurs modernes ont en horreur et dont ils veulent à tout prix départir les êtres et les choses au nom d’un « universalisme » qui n’est rien d’autre que la plus odieuse des hégémonies, la soumission des temporalités subtiles de l’âme au temps utilitaire, au faux destin de l’Histoire idolâtrée, à l’optimisme stupide, au nihilisme béat.  Que ce monde soit triste, torve, rancuneux et qu’il nous apparaisse tel sans que nous en eussions connu un autre suffit à convaincre qu’il n’est qu’un leurre, un mauvais rêve, un brouillard qui laisse deviner, derrière lui, une vérité éclatante mais encore plus ou moins informulée. Dominique de Roux fut exactement le contraire d’un nihiliste ; loin de nous ressasser que tout a déjà été dit, il nous donne à penser que presque tout reste à dire et même à créer : ainsi le Cinquième Empire dont la venue a pour condition le retour du Roi, un soir de brume sur le Tage ou le Nouveau Règne paraclétique de Stefan George ou encore l’Imam caché du prophétisme ismaélien.

Que ce monde soit triste, torve, rancuneux et qu’il nous apparaisse tel sans que nous en eussions connu un autre suffit à convaincre qu’il n’est qu’un leurre, un mauvais rêve, un brouillard qui laisse deviner, derrière lui, une vérité éclatante mais encore plus ou moins informulée. Dominique de Roux fut exactement le contraire d’un nihiliste ; loin de nous ressasser que tout a déjà été dit, il nous donne à penser que presque tout reste à dire et même à créer : ainsi le Cinquième Empire dont la venue a pour condition le retour du Roi, un soir de brume sur le Tage ou le Nouveau Règne paraclétique de Stefan George ou encore l’Imam caché du prophétisme ismaélien. Si le Paraclet est avenir, s’il est l’eschaton de notre destin, la foudre d’Apollon, elle, est déjà tombée, mais elle est aussi mystérieusement en chemin vers nous, comme voilée, encore insue. De son ultime chantre, ou victime, Hölderlin, qui incarne pour Dominique de Roux « la poésie absolue », il nous reste encore à déchiffrer les traces, ces « jours de fêtes » dans l’éclaircie de l’être, ces silhouettes à la fois augurales et nostalgiques sur les bords précis de la Garonne, dans la lumière d’or de Bordeaux, cet exil en forme de talvera de la patrie perdue et infiniment retrouvée.

Si le Paraclet est avenir, s’il est l’eschaton de notre destin, la foudre d’Apollon, elle, est déjà tombée, mais elle est aussi mystérieusement en chemin vers nous, comme voilée, encore insue. De son ultime chantre, ou victime, Hölderlin, qui incarne pour Dominique de Roux « la poésie absolue », il nous reste encore à déchiffrer les traces, ces « jours de fêtes » dans l’éclaircie de l’être, ces silhouettes à la fois augurales et nostalgiques sur les bords précis de la Garonne, dans la lumière d’or de Bordeaux, cet exil en forme de talvera de la patrie perdue et infiniment retrouvée.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Ce qui nous consterne en effet n'appartient pas au domaine des décisions, mais des indécisions… des changements de pied… des incertitudes permanentes.

Ce qui nous consterne en effet n'appartient pas au domaine des décisions, mais des indécisions… des changements de pied… des incertitudes permanentes.

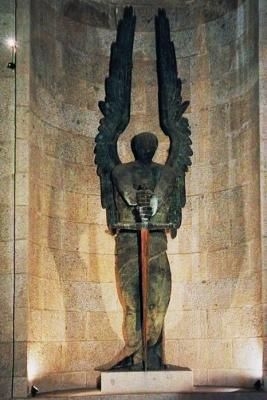

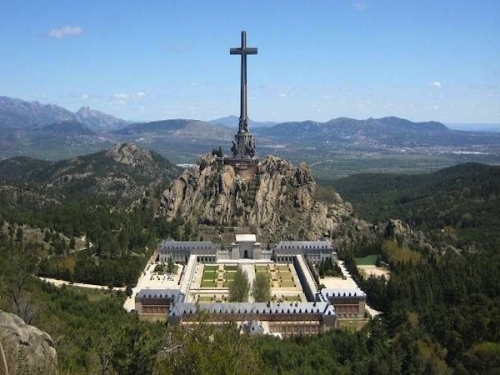

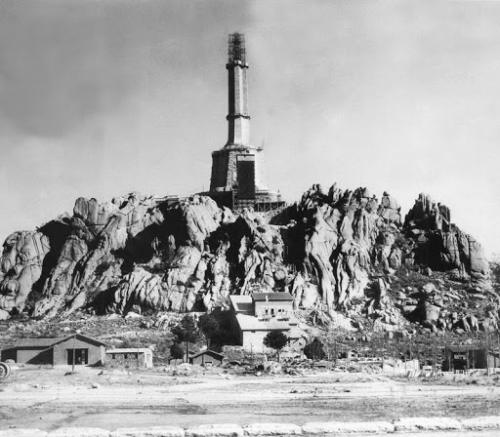

Juan de Avalos est le créateur des sculptures, en particulier des gigantesques têtes d’évangélistes au pied de la Croix. Avant la guerre civile, il militait dans les rangs des jeunesses socialistes et détenait la carte d’adhérent nº 7 du parti socialiste de Mérida. Autre détail piquant, le Christ qui domine l’autel majeur et qui repose sur une croix dont le bois de genévrier a été coupé par Franco, est l’œuvre d’un nationaliste basque, le sculpteur Julio Beobide, disciple du célèbre peintre Ignacio Zuloaga. C’est enfin un artiste catalan, Santiago Padrós, qui a conçu et réalisé l’impressionnante mosaïque de la coupole de la basilique (40 mètres de diamètre).

Juan de Avalos est le créateur des sculptures, en particulier des gigantesques têtes d’évangélistes au pied de la Croix. Avant la guerre civile, il militait dans les rangs des jeunesses socialistes et détenait la carte d’adhérent nº 7 du parti socialiste de Mérida. Autre détail piquant, le Christ qui domine l’autel majeur et qui repose sur une croix dont le bois de genévrier a été coupé par Franco, est l’œuvre d’un nationaliste basque, le sculpteur Julio Beobide, disciple du célèbre peintre Ignacio Zuloaga. C’est enfin un artiste catalan, Santiago Padrós, qui a conçu et réalisé l’impressionnante mosaïque de la coupole de la basilique (40 mètres de diamètre).

The Great Catastrophe

The Great Catastrophe

1.Observen este dato crucial: desde la transición, y aun antes, prácticamente todos los políticos, intelectuales y periodistas españoles, de cualquier partido, PSOE, PP o separatistas, han rivalizado en europeísmo. Casualmente nos han llevado entre todos a esta situación de democracia fallida y golpe de estado permanente.

1.Observen este dato crucial: desde la transición, y aun antes, prácticamente todos los políticos, intelectuales y periodistas españoles, de cualquier partido, PSOE, PP o separatistas, han rivalizado en europeísmo. Casualmente nos han llevado entre todos a esta situación de democracia fallida y golpe de estado permanente. Sí, algo de eso, pero, ¿has querido decir que las peripecias de la novela, como reflejo de las peripecias humanas, son pura vanidad? Ahora que lo dices, ¡el Eclesiastés se ha adelantado a Sartre, con otras palabras! ¡Me asombro, de verdad! Es lo que sostiene Moncho contra Santi, así que las reflexiones sobre el sol parecerían más propias de un nihilista que de un católico practicante, en fin, ya te he dado muchos consejos sobre cómo conducir la novela, que no te han convencido pero ahora lo veo claro: debía ser Moncho y no Santi quien fuera a ver la salida y la puesta del sol para convencerse de la inutilidad de la vida. Conste que yo simpatizo más con Santi.

Sí, algo de eso, pero, ¿has querido decir que las peripecias de la novela, como reflejo de las peripecias humanas, son pura vanidad? Ahora que lo dices, ¡el Eclesiastés se ha adelantado a Sartre, con otras palabras! ¡Me asombro, de verdad! Es lo que sostiene Moncho contra Santi, así que las reflexiones sobre el sol parecerían más propias de un nihilista que de un católico practicante, en fin, ya te he dado muchos consejos sobre cómo conducir la novela, que no te han convencido pero ahora lo veo claro: debía ser Moncho y no Santi quien fuera a ver la salida y la puesta del sol para convencerse de la inutilidad de la vida. Conste que yo simpatizo más con Santi. Hay otra analogía que hacer. El sol se oculta y llega la noche. De día tenemos luz, nos movemos, interactuamos unos con otros. La luz nos permite afrontar nuestros problemas y disfrutar de los momentos en que nos sentimos bien. Pero llega la noche y cesa todo eso. Todo lo que consideramos realidad se disuelve. Dormimos y perdemos la consciencia, estamos indefensos, no hay movimiento ni interacción, y la mente se puebla de imágenes extrañas y enigmáticas, de demonios. Recuerdo una vez en que mi mujer y yo fuimos a un pequeño yacimiento prehistórico en una colina desde la que se divisaba un gran panorama bajo el ocaso, lo he contado en Adiós a un tiempo. Y creí sentir lo que debía sentir un hombre prehistórico ante tal misterio, ante aquel tremendo fenómeno cósmico con tal exhibición de poder, del que dependía su vida y al mismo tiempo tan lejano y tan ajeno a él. El hombre actual urbano, intelectualizado, es poco capaz de sentir tales cosas. O las siente como una especie de diversión estética, que cabreaba a Santi. Como una cosa de consumo “bonito” que las agencias de viaje pueden venderte: “Tenemos una oferta para ti: disfruta de las puestas de sol del Caribe”.

Hay otra analogía que hacer. El sol se oculta y llega la noche. De día tenemos luz, nos movemos, interactuamos unos con otros. La luz nos permite afrontar nuestros problemas y disfrutar de los momentos en que nos sentimos bien. Pero llega la noche y cesa todo eso. Todo lo que consideramos realidad se disuelve. Dormimos y perdemos la consciencia, estamos indefensos, no hay movimiento ni interacción, y la mente se puebla de imágenes extrañas y enigmáticas, de demonios. Recuerdo una vez en que mi mujer y yo fuimos a un pequeño yacimiento prehistórico en una colina desde la que se divisaba un gran panorama bajo el ocaso, lo he contado en Adiós a un tiempo. Y creí sentir lo que debía sentir un hombre prehistórico ante tal misterio, ante aquel tremendo fenómeno cósmico con tal exhibición de poder, del que dependía su vida y al mismo tiempo tan lejano y tan ajeno a él. El hombre actual urbano, intelectualizado, es poco capaz de sentir tales cosas. O las siente como una especie de diversión estética, que cabreaba a Santi. Como una cosa de consumo “bonito” que las agencias de viaje pueden venderte: “Tenemos una oferta para ti: disfruta de las puestas de sol del Caribe”.

¿Cómo surgió la idea de escribir el librito “Vascos y Navarros”?

¿Cómo surgió la idea de escribir el librito “Vascos y Navarros”?

Lo que hace el Gobierno Vasco para la defensa de la lengua vasca me parece bastante acertado, a pesar de todas las acciones caricaturescas y desprovistas de sentido que han sido tomadas en contra del idioma castellano o -mejor dicho- del español, una de las dos o tres lengua más habladas del mundo. Ya sabemos que el idioma no es suficiente, pero además de esto no se debe esconder que los resultados de las políticas a favor del euskera son más bien escasos. La realidad es que no hay nación o patria posible sin un legado histórico combinado a un consentimiento y una voluntad de existencia por parte del pueblo. Nicolas Berdiaev y otros autores europeos famosos como Ortega y Gasset hablaban de unidad o comunidad de destino histórico. Pues bien, sin la combinación armoniosa del fundamento histórico-cultural y del factor voluntarista o consensual, sin esos dos ejes, no puede haber nación. Y por eso ya no hay hoy una verdadera nación española como no hay tampoco hoy verdaderas nacionalidades o naciones pequeñas dentro de España.

Lo que hace el Gobierno Vasco para la defensa de la lengua vasca me parece bastante acertado, a pesar de todas las acciones caricaturescas y desprovistas de sentido que han sido tomadas en contra del idioma castellano o -mejor dicho- del español, una de las dos o tres lengua más habladas del mundo. Ya sabemos que el idioma no es suficiente, pero además de esto no se debe esconder que los resultados de las políticas a favor del euskera son más bien escasos. La realidad es que no hay nación o patria posible sin un legado histórico combinado a un consentimiento y una voluntad de existencia por parte del pueblo. Nicolas Berdiaev y otros autores europeos famosos como Ortega y Gasset hablaban de unidad o comunidad de destino histórico. Pues bien, sin la combinación armoniosa del fundamento histórico-cultural y del factor voluntarista o consensual, sin esos dos ejes, no puede haber nación. Y por eso ya no hay hoy una verdadera nación española como no hay tampoco hoy verdaderas nacionalidades o naciones pequeñas dentro de España.

Similarly, I’ve also been watching on Fox News the steady procession of “proud,

Similarly, I’ve also been watching on Fox News the steady procession of “proud,  Among Scotchie’s topics and personalities for discussion, another that especially interested me, given my preoccupation with modern European history, is the essay devoted to British statesman

Among Scotchie’s topics and personalities for discussion, another that especially interested me, given my preoccupation with modern European history, is the essay devoted to British statesman