La société occidentale a développé des modèles ou des voies qui conduisent l’homme à s’éloigner des limites imposées par la nature, de la loi divine… ce sont ce que le Pape Jean-Paul II appelait des structures de péché.

En poursuivant votre navigation sur ce site, vous acceptez l'utilisation de cookies. Ces derniers assurent le bon fonctionnement de nos services. En savoir plus.

La stratégie américaine du gaz liquide contre l’Europe: la Pologne devient l’allié continental des Etats-Unis contre son propre environnement historique et politique !

Bruxelles/Varsovie: Les Etats-Unis ne laissent rien en plan pour torpiller le projet germano-russe du gazoduc “Nordstream 2” et parient de plus en plus nettement pour un partenariat gazier avec la Pologne.

Grâce à une augmentation des livraisons américaines de gaz liquide (lequel nuit à l’environnement et provient de la technique d’exploitation dite du “fracking” ou de la fracturation, interdite dans l’UE), la Pologne est sur la bonne voie pour devenir le carrefour d’acheminement du gaz américain en Europe centrale et orientale, en se débarrassant ainsi des acheminement traditionnels, qui suivent un axe Est/Ouest.

Entretemps, 12% du volume total des importations polonaises arrivent via un terminal installé à Swinemünde (Swinoujscie) en Poméranie ex-allemande. Un volume croissant de ce gaz provient des Etats-Unis. Ce glissement observable dans la politique énergétique polonaise vise bien évidemment la Russie. Maciej Wozniak, vice-président de l’entreprise PGNiG, appartenant pour moitié à l’Etat polonais, a expliqué récemment et sans circonlocutions inutiles aux médias : « Nous envisageons d’arrêter toute importation de gaz russe d’ici 2022 ».

Par ailleurs, PGNiG a pu, au cours de ces derniers mois, fournir un milliard de mètres cubes de gaz naturel à l’Ukraine. Outre cette livraison de gaz à l’Ukraine, on observe l’émergence, en Pologne, d’un réseau de gazoducs qui, dans l’avenir, acheminera du gaz importé d’outre-mer vers les pays de l’Europe de l’Est et du Sud-Est. Le ministre américain des affaires étrangères, Rex Tillerson, a déclaré que les Etats-Unis soutiendraient le projet. On devine aisément que c'est pour des raisons géostratégiques évidentes!

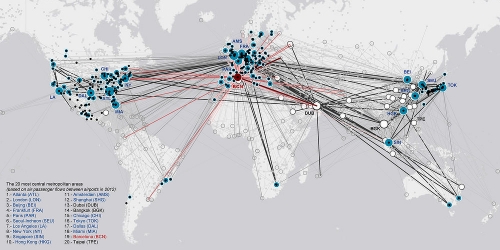

L’eurocratie bruxelloise, elle aussi, soutient, avec l’argent des contribuables européens et avec le soutien américain, la construction et le développement de sites d’arrivée et de débarquement de gaz naturel ou liquide ainsi que de gazoducs venant de Scandinavie pour aboutir en Europe orientale voire en Azerbaïdjan et au Turkménistan, pour faire concurrence au projet germano-russe « Nordstream 2 » et pour limiter l’influence dominante de Gazprom, le consortium russe du gaz naturel. Le programme « Connecting Europe Facility » (CEF) installe des ports d’importation de gaz liquide en provenance de la Mer du Nord en Baltique et en Méditerranée. Le système des gazoducs, qui y est lié, forme un demi-cercle parfait autour du territoire de la Fédération de Russie. Le gaz qui est importé via ce système provient de plus en plus de pays où les gisements sont exploités par la méthode de « fracking » (de « fracturation »), laquelle est préjudiciable à l’environnement : ces pays sont le Canada, les Etats-Unis et l’Autstralie.

Dans ce contexte, les Etats-Unis, la Pologne et les Pays baltes poursuivent des intérêts économiques et politiques particuliers : ils veulent imposer un bloc anti-russe, d’inspiration transatlantique, aux pays de l’Europe orientale membres de l’UE et à tous leurs voisins d’Europe de l’Est, au détriment de la coopération entre Européens et Russes, déjà mise à mal par les sanctions que l’Occident impose à la Russie.

Articld paru sur : http://www.zuerst.de

10:24 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes, Géopolitique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : gaz de schiste, gaz liquide, fracking, gazoducs, hydrocarbures, politique internationale, géopolitique, actualité, europe, affaires européennes, énergie, union européenne, pologne, états-unis |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

09:34 Publié dans Philosophie, Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : définitions, philosophie, philosophie politique, christianisme, chrétienté, catholicisme, théorie politique, politologie, sciences politiques |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

par Jean Paul Baquiast

Ex: http://www.europesolidaire.eu

Le Parlement ukrainien avait voté le 18 janvier 20I8 dernier une loi sur la réintégration du Donbass dans la République d'Ukraine. Il en a été peu parlé à ce jour en Europe. Il s'agit en fait d'une bombe à retardement.

La loi vise à restaurer « l'intégrité territoriale » du pays, et désigne les territoires de Donetsk et de Louhansk, dans la région du Donbass, comme «occupés» par la Russie. Elle dénonce nommément une «agression russe». L'évènement a été peu commenté, notamment en Allemagne et en France, pourtant signataires de l'accord dit de Minsk 2 https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Minsk_II visant à établir un cessez-le feu. L'accord n'avait jamais été respecté par Kiev qui a multiplié les agressions contre les russophones du Donbass, entrainant plus de 10.000 de morts chez les civils, sans mentionner la destruction de quartiers urbains entiers.

Avec la nouvelle loi les opérations dites « anti-terroristes » de Kiev n'auront plus lieu d'être puisque c'est l'armée régulière ukrainienne qui réprimera tous les mouvements séparatistes. Le président ukrainien Petro Porochenko a vu également ses pouvoirs considérablement élargis. Il lui revient notamment de déterminer la limite des territoires occupés, ainsi que des zones de sécurité près des lieux de combats.

La loi sur la réintégration du Donbass ne comporte aucune mention des accords de Minsk, signés en 2015 avec la médiation de la Russie, de la France et de l'Allemagne, visant à une désescalade de la tension et à une démilitarisation dans la région disputée par les autonomes pro-russes et les forces loyalistes.

La "main de Washington"

En décembre 2017, Washington avait annoncé renforcer son soutien à Kiev en fournissant des armes létales. La porte-parole de la diplomatie américaine, Heather Nauert, avait expliqué le renforcement comme une aide visant à «bâtir sa défense sur le long terme, défendre sa souveraineté, son intégrité territoriale et se prémunir de toute agression à venir».

Il est évident que le Pentagone souhaite pousser les Russes à intervenir militairement, ce qui lui donnerait un prétexte, au nom notamment de l'Otan, de répondre par les mêmes moyens militaires. Mais jusqu'ici Vladimir Poutine s'en était gardé, sachant bien que ceci pourrait dégénérer rapidement en guerre mondiale. Mais son opposition lui avait reproché sa passivité. On peut penser qu'il continuera à s'abstenir, malgré les appels au secours que ne cessent de lui adresser les Républiques auto-proclamées de Lougansk et de Donetsk .

Tout laisse craindre une intensification des attaques de Kiev contre ces deux républiques, utilisant les nombreux armements lourds procurés par les Etats-Unis. Il est peu probable cependant que les russophones, directement menacés désormais de déportations et de fusillades, se soumettent.

Il faut donc s'attendre dans les prochaines semaines à une intensification des combats et un accroissement important des morts parmi les civils du Donbass. Beaucoup de bruit est fait actuellement sur les morts de la région de la Ghutta en Syrie que cherche à réoccuper Bashar el Assad, mais curieusement un silence épais s'est fait sur ce qui se passe et sur ce qui se prépare dans le Donbass.

La moindre des choses que l'on attendrait de l'Allemagne et de la France signataires de Minsk 2, seraient qu'elles interviennent, au moins diplomatiquement, en accord avec la Russie, pour prévenir les massacres qui se préparent.

Pour plus de détails, on pourra lire l'article Ukraine passes Donbass 'reintegration' law, effectively terminating Minsk peace accord http://russiafeed.com/and-so-it-begins-donbass-reintegrat... Bien qu'il émane d'une source proche des Russes, nous n'avons pour notre part rien trouvé de fondamental à en redire.

08:52 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes, Géopolitique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, géopolitique, politique internationale, ukraine, europe, donbass, affaires européennes |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Guerra, política y partido

“La revolución proletaria no puede triunfar sin un partido, por fuera de un partido, contra un partido o con un sustituto para un partido. Esa es la principal enseñanza de los diez últimos años” (León Trotsky, Lecciones de Octubre).

El desborde ocurrido en las jornadas del 14 y 18 de diciembre ha puesto sobre la mesa la discusión sobre las relaciones entre guerra y política. A pesar de su campaña contra los “violentos”, el único violento fue el gobierno: reprimiendo una concentración de masas sobre el fondo del repudio masivo a la ley antijubilatoria, era inevitable que su acción represiva desatara una dura respuesta de los sectores movilizados.

La “gimnasia” del enfrentamiento a la represión dejó un sinnúmero de enseñanzas. Entre ellas, una central: las relaciones entre lucha política y lucha física: el pasaje de la lucha política a la acción directa.

Esta problemática ha sido abordada por el marxismo sobre todo a partir de la Revolución Rusa. Si bien con antecedentes en los estudios de Marx y Engels, y también los debates en la socialdemocracia alemana (que tuvo como gran protagonista a Rosa Luxemburgo), fueron Lenin y Trotsky los que le dieron vuelo a las investigaciones sobre las relaciones entre ambos órdenes sociales[1].

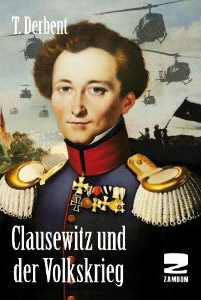

La fuente básica de los marxistas ha sido siempre Karl von Clausewitz, oficial del ejército prusiano, que a comienzos del siglo XIX y resumiendo la experiencia de los ejércitos napoleónicos, escribió su clásico tratado De la Guerra que hasta hoy expresa uno de los abordajes más profundos de dicho evento.

Clausewitz iniciaba su estudio con una sentencia que rompía con el sentido común de la época, cuando señalaba que la guerra no es una esfera social autónoma sino “la continuidad de la política bajo otras formas”, formas violentas.

Lenin y Trotsky recuperarían sus definiciones dándoles terrenalidad en la experiencia misma de la revolución: en el evento por antonomasia del pasaje de la política a la lucha física: la ciencia y arte de la insurrección: el momento en que se rompe el continuum de la historia con la intervención de las masas comandadas por el partido revolucionario, que se hacen del poder y cambian la historia.

Lenin y Trotsky recuperarían sus definiciones dándoles terrenalidad en la experiencia misma de la revolución: en el evento por antonomasia del pasaje de la política a la lucha física: la ciencia y arte de la insurrección: el momento en que se rompe el continuum de la historia con la intervención de las masas comandadas por el partido revolucionario, que se hacen del poder y cambian la historia.

Si, en definitiva, la lucha política es una lucha de partidos, la insurrección como evento máximo de traducción de la política al enfrentamiento físico, no tiene otra alternativa que ser comandado por un partido. Volveremos sobre esto.

A la insurrección de Octubre le seguiría la experiencia de Trotsky al frente del Ejército Rojo durante la guerra civil; las enseñanzas desprendidas de dicho evento.

A partir de la experiencia, y de la elaboración teórica desprendida de la misma, se fue forjando un corpus de conceptos, donde un lugar no menor lo ocupan las categorías de estrategia y táctica; la estrategia, que tiene que ver con el conjunto total de los enfrentamientos que llevan al triunfo en la confrontación; la táctica, relacionada con los momentos parciales de dicho enfrentamiento: los momentos específicos donde se pone a prueba la estrategia misma; estrategia que, como decía Clausewitz, debe entrar en el combate con el ejército y corregirse a la luz de sus desarrollos.

De ahí que esta elaboración tenga que ver con el pasaje de la política a la guerra: con aquel momento donde los enfrentamientos se sustancian en el lenguaje de la lucha física; lucha física que, de todas maneras, siempre está comandada por la política: “Bajo el influjo de Sharnhorst, Clausewitz se interesó por la visión histórica de la guerra (…) y llega a la temprana conclusión de que la política es el ‘alma’ de la guerra” (José Fernández Vega, Carl von Clausewitz. Guerra, política y filosofía).

La guerra como continuidad de la política

Desde Clausewitz guerra y política son esferas estrechamente relacionadas. Lenin y Trotsky retomaron esta definición del gran estratega militar alemán de comienzos del siglo XIX. Se apoyaron en Engels, que ya a mediados del siglo XIX le había comentado a Marx el “agudo sentido común” de los escritos de Clausewitz. También Franz Mehring, historiador de la socialdemocracia alemana y uno de los aliados de Rosa Luxemburgo, se había interesado por la historia militar y reivindicaba a Clausewitz.

Por otra parte, hacia finales de la II Guerra Mundial, en el pináculo de su prestigio, Stalin rechazó a Clausewitz con el argumento de que la opinión favorable que tenía Lenin acerca de éste se debía a que “no era especialista en temas militares”…

Pierre Naville señalaría que el Frente Oriental y el triunfo militar del Ejército Rojo sobre la Wehrmacht, había confirmado la tesis contraria: la validez de Clausewitz y lo central de sus intuiciones militares; entre otras, la importancia de las estrategias defensivas en la guerra.

Según su famosa definición, para Clausewitz “la guerra es la continuación de la política por otros medios”. Quedaba así establecida una relación entre guerra y política que el marxismo hizo suya. La guerra es una forma de las relaciones sociales cuya lógica está inscripta en las relaciones entre los Estados, pero que el marxismo ubicó, por carácter transitivo, en la formación de clase de la sociedad. La guerra, decía Clausewitz, debe ser contemplada “como parte de un todo”, y ese todo es la política, cuyo contenido, para el marxismo, es la lucha de clases.

Con agudeza, el teórico militar alemán sostenía que la guerra debía ser vista como un “elemento de la contextura social”, que es otra forma de designar un conflicto de intereses solucionado de manera sangrienta, a diferencia de los demás conflictos.

Esto no quiere decir que la guerra no tenga sus propias especificidades, sus propias leyes, que requieren de un análisis científico de sus determinaciones y características. Desde la Revolución Francesa, pasando por las dos guerras mundiales y las revoluciones del siglo XX, la ciencia y el arte de la guerra se enriquecieron enormemente. Tenemos presentes las guerras bajo el capitalismo industrializado y las sociedades pos-capitalistas como la ex URSS, y el constante revolucionamiento de la ciencia y la técnica guerrera.

Las relaciones entre técnica y guerra son de gran importancia; ya Marx había señalado que muchos desarrollos de las fuerzas productivas ocurren primero en el terreno de la guerra y se generalizan después a la economía civil.

Las dos guerras mundiales fueron subproducto del capitalismo industrial contemporáneo: la puesta en marcha de medios de destrucción masivos, el involucramiento de las grandes masas, la aplicación de los últimos desarrollos de la ciencia y la técnica a la producción industrial y a las estrategias de combate (Traverso).

Esto dio lugar a toda la variedad imaginable en materia de guerra de posiciones y de maniobra: con cambios de frente permanentes y de magnitud, con la aparición de la aviación, los medios acorazados, los submarinos, la guerra química y nuclear y un largo etcétera[2].

Como conclusión, cabe volver a recordar lo señalado por Trotsky a partir de su experiencia en la guerra civil: no hay que atarse rígidamente a ninguna de las formas de la lucha: la ofensiva y la defensa son características que dependen de las circunstancias. Y, en su generalidad, la experiencia de la guerra ha consagrado la vigencia de las enseñanzas de Clausewitz, que merecen un estudio profundo por parte de la nueva generación militante.

La política como “guerra de clases”

Ahora bien, si la guerra es la continuidad de la política por otros medios, a esta fórmula le cabe cierta reversibilidad: “Si la guerra puede ser definida como la continuidad de la política por otros medios, [la política] deviene, recíprocamente, la continuidad de la guerra fuera de sus límites por sus propios medios. Ella también es un arte del tiempo quebrado, de la coyuntura, del momento propicio para arribar a tiempo ‘al centro de la ocasión” (Bensaïd, La política como arte estratégico).

De ahí que muchos de los conceptos de la guerra se vean aplicados a la política, ya que ésta es, como la guerra, un campo para hacer valer determinadas relaciones de fuerza. Sin duda, las relaciones de fuerza políticas se hacen valer mediante un complejo de relaciones mayor y más rico que el de la violencia desnuda, pero en el fondo en el terreno político también se trata de vencer la resistencia del oponente.

De ahí que muchos de los conceptos de la guerra se vean aplicados a la política, ya que ésta es, como la guerra, un campo para hacer valer determinadas relaciones de fuerza. Sin duda, las relaciones de fuerza políticas se hacen valer mediante un complejo de relaciones mayor y más rico que el de la violencia desnuda, pero en el fondo en el terreno político también se trata de vencer la resistencia del oponente.

En todo caso, la política como arte ofrece más pliegues, sutilezas y complejidades que la guerra, como señalaría Trotsky, que agregaba que la guerra (y ni hablar cuando se trata de la guerra civil, su forma más cruenta), debe ser peleada ajustándose a sus propias leyes, so pena de sucumbir: “Clausewitz se opone a las concepciones absolutistas de la guerra [que la veían como una suerte de ceremonia y de juego] y enfatiza el ‘elemento brutal’ que toda guerra contiene” (Vega, ídem).

De allí que se pueda definir a la política (metafóricamente) como continuidad de la “guerra” que cotidianamente se sustancia entre las clases sociales explotada y explotadora. Así, la política es una manifestación de la guerra de clases que recorre la realidad social bajo la explotación capitalista. Esta figura puede ayudar a apreciar la densidad de lo que está en juego, superando la mirada a veces ingenua de las nuevas generaciones.

Nada de esto significa que tengamos una concepción militarista de las cosas. Todo lo contrario: el militarismo es una concepción reduccionista que pierde de vista el espesor de la política revolucionaria, y que deja de lado a las grandes masas, reemplazadas por la técnica y el herramental de guerra, a la hora de los eventos históricos.

Es característico del militarismo hacer primar la guerra sobre la política, algo común tanto a las políticas de las potencias imperialistas como a las formaciones guerrilleras pequeño-burguesas de los años 70: perdían de vista a las grandes masas como actores y protagonistas de la historia.

Tal era la posición del general alemán de la I Guerra Mundial, Erich von Ludendorff, autor de la obra La guerra total (1935), donde criticaba a Clausewitz desde una posición reduccionista que ponía en el centro de las determinaciones a la categoría de “guerra total”, a la que independizaba de la política negando el concepto clausewitziano de “guerra absoluta”, que necesariamente se ve limitado por las determinaciones políticas.

Tal era la posición del general alemán de la I Guerra Mundial, Erich von Ludendorff, autor de la obra La guerra total (1935), donde criticaba a Clausewitz desde una posición reduccionista que ponía en el centro de las determinaciones a la categoría de “guerra total”, a la que independizaba de la política negando el concepto clausewitziano de “guerra absoluta”, que necesariamente se ve limitado por las determinaciones políticas.

A su modo de ver De la guerra era “el resultado de una evolución histórica hoy anacrónica y desde todo punto de vista sobrepasada” (Darío de Benedetti, ídem).

Para Ludendorff y los teóricos del nazismo, lo “originario” era el “estado de guerra permanente”; la política, solamente uno de sus instrumentos. De ahí que se considerara la paz simplemente como “un momento transitorio entre dos guerras”.

En esa apelación a la “guerra total” las masas, el Volk, eran vistas como un instrumento pasivo: pura carne de cañón en la contienda: “Ludendorff olvida el factor humano, las fuerzas morales según Clausewitz, como factor decisivo de toda movilización (…) [apela a] un verdadero proceso de cosificación, que permite una total disposición de medios para su alcance” (de Benedetti, ídem).

Pero lo cierto es lo contrario: si la guerra no es más que la continuidad de la política por medios violentos, es la segunda la que fija los objetivos de la primera: “En el siglo XVIII aún predominaba la concepción primitiva según la cual la guerra es algo independiente, sin vinculación alguna con la política, e, inclusive, se concebía la guerra como lo primario, considerando la política más bien como un medio de la guerra; tal es el caso de un estadista y jefe de campo como fue el rey Federico II de Prusia. Y en lo que se refiere a los epígonos del militarismo alemán, los Ludendorff y Hitler, con su concepción de la ‘guerra total’, simplemente invirtieron la teoría de Clausewitz en su contrario antagónico” (AAVV, Clausewitz en el pensamiento marxista).

Con esta suerte de “analogía” entre la política y la guerra lo que buscamos es dar cuenta de la íntima conflictividad de la acción política; superar toda visión ingenua o parlamentarista de la misma. La política es un terreno de disputa excluyente donde se afirman los intereses de la burguesía o de la clase obrera. No hay conciliación posible entre las clases en sentido último; esto le confiere todos los rasgos de guerra implacable a la lucha política.

La política revolucionaria, no la reformista u electoralista, tiene esa base material: la oposición irreconciliable entre las clases, como destacara Lenin. Lo que no obsta para que los revolucionarios tengamos la obligación de utilizar la palestra parlamentaria, hacer concesiones y pactar compromisos.

Pero la utilización del parlamento, o el uso de las maniobras, debe estar presidida por una concepción clara acerca de ese carácter irreconciliable de los intereses de clase, so pena de una visión edulcorada de la política, emparentada no con las experiencias de las grandes revoluciones históricas, sino con los tiempos posmodernos y “destilados” de la democracia burguesa y el “fin de la historia” que, como señalara Bensaïd, pretenden reducir a cero la idea misma de estrategia.

Crítica del militarismo

El criterio principista de tipo estratégico que preside al marxismo revolucionario es que todas las tácticas y estrategias deben estar al servicio de la autodeterminación revolucionaria de la clase obrera, de su emancipación. Sobre la base de las lecciones del siglo XX, debe ser condenado el sustituismo social de la clase obrera como estrategia y método para lograr los objetivos emancipatorios del proletariado.

El sustituismo como estrategia, simplemente, no es admisible para los socialistas revolucionarios. Toda la experiencia del siglo XX atestigua que si no está presente la clase obrera, su vanguardia, sus organismos de lucha y poder, sus programas y partidos, si no es la clase obrera con sus organizaciones la que toma el poder, la revolución no puede progresar de manera socialista: queda congelada en el estadio de la estatización de los medios de producción, lo que, a la postre, no sirve a los objetivos de la acumulación socialista sino de la burocracia.

Un ejemplo vivido por los bolcheviques a comienzos de 1920 fue la respuesta al ataque desde Polonia decidida por el dictador Pilsudsky en el marco de la guerra civil, ataque que desató una contraofensiva del Ejército Rojo que atravesó la frontera rusa y llegó hasta Varsovia. Durante unas semanas dominó el entusiasmo que “desde arriba”, militarmente, se podía extender la revolución. Uno de los principales actores de este empuje fue el talentoso y joven general Tujachevsky (asesinado por Stalin en las purgas de los años 30[3]).

Esta acción fue explotada por la dictadura polaca de Pilsudsky como “un avasallamiento de los derechos nacionales polacos”, y no logró ganar el favor de las masas obreras y mucho menos campesinas, por lo que terminó en un redondo fracaso.

Trotsky, que con buen tino se había opuesto a la misma[4], sacó la conclusión que una intervención militar en un país extranjero desde un Estado obrero, puede ser un punto de apoyo secundario y/o auxiliar en un proceso revolucionario, nunca la herramienta fundamental: “En la gran guerra de clases actual la intervención militar desde afuera puede cumplir un papel concomitante, cooperativo, secundario. La intervención militar puede acelerar el desenlace y hacer más fácil la victoria, pero sólo cuando las condiciones sociales y la conciencia política están maduras para la revolución. La intervención militar tiene el mismo efecto que los fórceps de un médico; si se usan en el momento indicado, pueden acortar los dolores del parto, pero si se usan en forma prematura, simplemente provocarán un aborto” (en E. Wollenberg, El Ejército Rojo, p. 103).

De ahí que toda la política, la estrategia y las tácticas de los revolucionarios deban estar al servicio de la organización, politización y elevación de la clase obrera a clase dominante; que no sea admisible su sustitución a la hora de la revolución social por otras capas explotadas y oprimidas aparatos políticos y/o militares ajenos a la clase obrera misma (otra cosa son las alianzas de clases explotadas y oprimidas imprescindibles para tal empresa).

El criterio de la autodeterminación y centralidad de la clase obrera en la revolución social, es un principio innegociable. Y no sólo es un principio: hace a la estrategia misma de los socialistas revolucionarios en su acción.

Otra cosa es que las relaciones entre masas, partidos y vanguardia sean complejas, no admitan mecanicismos. Habitualmente los factores activos son la amplia vanguardia y las corrientes políticas, mientras que las grandes masas se mantienen pasivas y sólo entran en liza cuando se producen grandes conmociones, algo que, como decía Trotsky, era signo inequívoco de toda verdadera revolución.

Ocurre una inevitable dialéctica de sectores adelantados y atrasados en el seno de la clase obrera a la hora de la acción política; no se debe buscar el “mínimo común denominador” adaptándose a los sectores atrasados sino, por el contrario, ganar la confianza de los sectores más avanzados para empujar juntos a los más atrasados.

Incluso más: puede haber circunstancias de descenso en las luchas del proletariado y el partido -más aún si está en el poder- verse obligado a ser una suerte de nexo o “puente” entre el momento actual de pasividad y un eventual resurgimiento de las luchas en un período próximo. No tendrá otra alternativa que “sustituir”, transitoriamente, la acción de la clase obrera en defensa de sus intereses inmediatos e históricos.

Algo de esto afirmaba Trotsky que le había ocurrido al bolchevismo a comienzos de los años 20, luego de que la clase obrera y las masas quedaran exhaustas a la salida de la guerra civil[5]. Pero el criterio es que aun “sustituyéndola”, se deben defender los intereses inmediatos e históricos de la clase obrera. Y esta “sustitución” sólo puede ser una situación transitoria impuesta por las circunstancias, so pena de transformarse en otra cosa[6].

Ya la teorización del sustituismo social de la clase obrera en la revolución socialista pone las cosas en otro plano: es una justificación de la acción de una dirección burocrática y/o pequeñoburguesa que, si bien puede terminar yendo más lejos de lo que ella preveía en el camino del anticapitalismo, nunca podrá sustituir a la clase obrera al frente del poder. Porque esto amenaza que se terminen imponiendo los intereses de una burocracia y no los de la clase obrera (como ocurrió en el siglo XX).

Quebrar el movimiento inercial

De lo anterior se desprende otra cuestión: la apelación a los métodos de lucha de la clase obrera en contra del terrorismo individual o de las minorías que empuñan las armas en “representación” del conjunto de los explotados y oprimidos.

En el siglo pasado han habido muchas experiencias: el caso de las formaciones guerrilleras latinoamericanas, y del propio Che Guevara, que excluían por definición los métodos de lucha de masas en beneficio de los “cojones”: una “herramienta central” de la revolución, porque la clase obrera estaba, supuestamente, “aburguesada”…

Un caso similar fue el del PCCh bajo Mao. La pelea contra el sustituismo social de la clase obrera tiene que ver con que los revolucionarios no “inventamos nada”: no creamos artificialmente los métodos de pelea y los organismos de lucha y poder. Más bien ocurre lo contrario: buscamos hacer consciente su acción, generalizar esas experiencias e incorporarlas al acervo de enseñanzas de la clase obrera.

Esta era una preocupación característica de Rosa Luxemburgo, que insistía en la necesidad de aprender de la experiencia real de la clase obrera, contra el conservadurismo pedante y de aparato de la vieja socialdemocracia.

Esta era una preocupación característica de Rosa Luxemburgo, que insistía en la necesidad de aprender de la experiencia real de la clase obrera, contra el conservadurismo pedante y de aparato de la vieja socialdemocracia.

Vale destacar también la ubicación de Lenin frente al surgimiento de los soviets en 1905. Los “bolcheviques de comité”, demasiado habituados a prácticas sectarias y conservadoras, se negaban a entrar en el Soviet de Petrogrado porque éste “no se declaraba bolchevique”… Lenin insistía que la orientación debía ser “Soviets y partido”, no contraponer de manera pedante y ultimatista, unos y otros.

Sobre la cuestión del armamento popular rechazamos las formaciones militares que actúan en sustitución de la clase obrera, así como el terrorismo individual, y por las mismas razones. Pero debemos dejar a salvo no sólo la formación de ejércitos revolucionarios como el Ejército Rojo, evidentemente, también experiencias como la formación de milicias obreras y populares o las dependientes de las organizaciones revolucionarias.

Este último fue el caso del POUM y los anarquistas en la Guerra Civil española, más allá del centrismo u oportunismo de su política. Y podrían darse circunstancias similares en el futuro que puedan ser englobadas bajo la orientación del armamento popular.

Agreguemos algo más vinculado a la guerra de guerrillas. En Latinoamérica, en la década del 70, las formaciones foquistas o guerrilleras, rurales o urbanas, reemplazaban con sus “acciones” la lucha política revolucionaria (las acciones de masas y la construcción de partidos de la clase obrera).

Sin embargo, este rechazo a la guerra de guerrillas como estrategia política, no significa descartarla como táctica militar. Si es verdad que se trata de un método de lucha habitualmente vinculado a sectores provenientes del campesinado (o de sectores más o menos “desclasados”), bajo condiciones extremas de ocupación militar del país por fuerzas imperialistas, no se debe descartar la eventualidad de poner en pie formaciones de este tipo íntimamente vinculadas a la clase trabajadora. Esto con un carácter de fuerza auxiliar similar a una suerte de milicia obrera, y siempre subordinada al método de lucha principal, que es la lucha de masas[7].

Pasemos ahora a las alianzas de clases y la hegemonía que debe alcanzar la clase obrera a la hora de la revolución. Si la centralidad social en la revolución corresponde a la clase obrera, ésta debe tender puentes hacia el resto de los sectores explotados y oprimidos.

Para que la revolución triunfe, debe transformarse en una abrumadora mayoría social. Y esto se logra cuando la clase obrera logra elevarse a los intereses generales y a tomar en sus manos las necesidades de los demás sectores explotados y oprimidos.

Es aquí donde el concepto de alianza de clases explotadas y oprimidas se transforma en uno análogo: hegemonía. La hegemonía de la clase obrera a la hora de la revolución socialista corresponde al convencimiento de los sectores más atrasados, de las capas medias, del campesinado, de que la salida a la crisis de la sociedad ya no puede provenir de la mano de la burguesía, sino solamente del proletariado.

Este problema es clásico a toda gran revolución. Si la Revolución Francesa de 1789 logró triunfar es porque desde su centro excluyente, París, logró arrastrar tras de sí al resto del país. Algo que no consiguió la Comuna de París cien años después, lo que determinó su derrota. El mismo déficit tuvo el levantamiento espartaquista de enero de 1919 en Alemania, derrotado a sangre y fuego porque el interior campesino y pequeño-burgués no logró ser arrastrado. Multitudinarias movilizaciones ocurrían en Berlín enfervorizando a sus dirigentes (sobre todo a Karl Liebknecht; Rosa era consciente de que se iba al desastre), mientras que en el interior el ejército alemán se iba reforzando y fortaleciendo con el apoyo del campesinado y demás sectores conservadores.

Este problema es clásico a toda gran revolución. Si la Revolución Francesa de 1789 logró triunfar es porque desde su centro excluyente, París, logró arrastrar tras de sí al resto del país. Algo que no consiguió la Comuna de París cien años después, lo que determinó su derrota. El mismo déficit tuvo el levantamiento espartaquista de enero de 1919 en Alemania, derrotado a sangre y fuego porque el interior campesino y pequeño-burgués no logró ser arrastrado. Multitudinarias movilizaciones ocurrían en Berlín enfervorizando a sus dirigentes (sobre todo a Karl Liebknecht; Rosa era consciente de que se iba al desastre), mientras que en el interior el ejército alemán se iba reforzando y fortaleciendo con el apoyo del campesinado y demás sectores conservadores.

Precisamente en esa apreciación fundaba Lenin la ciencia y el arte de la insurrección: en una previsión que debía responder a un análisis lo más científico posible, pero también a elementos intuitivos, acerca de qué pasaría una vez que el proletariado se levantase en las ciudades.

El proletariado se pone de pie y toma el poder en la ciudad capital. Pero la clave de la insurrección, y la revolución misma, reside en si logra arrastrar activamente o, al menos, logra un apoyo pasivo, tácito, o incluso la “neutralidad amistosa” (Trotsky), de las otras clases explotadas y oprimidas en el interior.

De ahí que alianza de clases, hegemonía y ciencia y arte de la insurrección tengan un punto de encuentro en el logro de la mayoría social de la clase obrera a la hora de la toma del poder.

Una apreciación que requerirá de todas las capacidades de la organización revolucionaria en el momento decisivo, y que es la mayor prueba a la que se puede ver sometido un partido digno de tal nombre: “Todas estas cartas [se refiere a las cartas de Lenin a finales de septiembre y comienzos de octubre de 1917], donde cada frase estaba forjada sobre el yunque de la revolución, presentan un interés excepcional para caracterizar a Lenin y apreciar el momento. Las inspira el sentimiento de indignación contra la actitud fatalista, expectante, socialdemócrata, menchevique hacia la revolución, que era considerada como una especie de película sin fin. Si en general el tiempo es un factor importante de la política, su importancia se centuplica en la época de guerra y de revolución. No es seguro que se pueda hacer mañana lo que puede hacerse hoy (…).

“Pero tomar el poder supone modificar el curso de la historia. ¿Es posible que tamaño acontecimiento deba depender de un intervalo de veinticuatro horas? Claro que sí. Cuando se trata de la insurrección armada, los acontecimientos no se miden por el kilómetro de la política, sino por el metro de la guerra. Dejar pasar algunas semanas, algunos días; a veces un solo día sin más, equivale, en ciertas condiciones, a la rendición de la revolución, a la capitulación (…).

“Desde el momento en que el partido empuja a los trabajadores por la vía de la insurrección, debe extraer de su acto todas las consecuencias necesarias. À la guerre comme à la guerre [en la guerra como en la guerra]. Bajo sus condiciones, más que en ninguna otra parte, no se pueden tolerar las vacilaciones y las demoras. Todos los plazos son cortos. Al perder tiempo, aunque no sea más que por unas horas, se le devuelve a las clases dirigentes algo de confianza en sí mismas y se les quita a los insurrectos una parte de su seguridad, pues esta confianza, esta seguridad, determina la correlación de fuerzas que decide el resultado de la insurrección” (Trotsky, Lecciones de Octubre).

El partido como factor decisivo de las relaciones de fuerzas

Veremos someramente ahora el problema del partido como factor organizador permanente y como factor esencial de la insurrección.

El partido no agrupa a los trabajadores por su condición de tales sino solamente aquéllos que han avanzado a la comprensión de que la solución a los problemas pasa por la revolución socialista: el partido agrupa a los revolucionarios y no a los trabajadores en general (cuya abrumadora mayoría es de ideología burguesa, reformista y no revolucionaria).

El partido no agrupa a los trabajadores por su condición de tales sino solamente aquéllos que han avanzado a la comprensión de que la solución a los problemas pasa por la revolución socialista: el partido agrupa a los revolucionarios y no a los trabajadores en general (cuya abrumadora mayoría es de ideología burguesa, reformista y no revolucionaria).

Quienes se agrupan bajo un mismo programa constituyen un partido. Pero si sus militantes no construyen el partido, no lo construye nadie: el partido es lo menos objetivo y espontáneo que hay respecto de las formas de la organización obrera: requiere de un esfuerzo consciente y adicional, con leyes propias.

Un problema muy importante es el de la combinación de los intereses del movimiento en general y los del partido en particular a la hora de la intervención política. Un error habitual es sacrificar unos en el altar de los otros.

En el caso de las tendencias más burocráticas, lo que se sacrifica son los intereses generales de los trabajadores en función de los del propio aparato. Ya Marx sostenía que los comunistas sólo se caracterizaban por ser los que, en cada caso, hacían valer los intereses generales del movimiento.

Pero es también una concepción falsa creer que los intereses del partido nunca valen; que sólo vale el interés “general”, sacrificando ingenuamente los intereses del propio partido.

Así se hace imposible construir el partido, cuya mecánica de construcción es la menos “natural”. Precisamente por esto hay que aprender a sostener ambos intereses: las condiciones generales de la lucha y la construcción del partido a partir de ellas. Además, hay que saber evaluar qué interés es el que está en juego en cada caso. Nunca se puede correr detrás de toda lucha, de todo acontecimiento; no hay partido que lo pueda hacer.

Pero cuando se trata de organizaciones de vanguardia, hay que elegir. Hay que jerarquizar considerando el peso del hecho objetivo, y también las posibilidades del partido de responder y construirse en esa experiencia.

Esto significa que no siempre la agenda partidaria se ordena alrededor de la agenda “objetiva” de la realidad. Hay que considerar la agenda de la propia organización a la hora de construirse, sus propias iniciativas: “La observación más importante que se puede hacer a propósito de todo análisis concreto de la correlación de fuerzas es que estos análisis no pueden ni deben ser análisis en sí mismos (a menos que se escriba un capítulo de historia del pasado), sino que sólo adquieren significado si sirven para justificar una actividad práctica, una iniciativa de voluntad. Muestran cuáles son los puntos de menor resistencia donde puede aplicarse con mayor fruto la fuerza de la voluntad; sugieren las operaciones tácticas inmediatas; indican cómo se puede plantear mejor una campaña de agitación política, qué lenguaje entenderán mejor las multitudes, etc. El elemento decisivo de toda situación es la fuerza permanentemente organizada y dispuesta desde hace tiempo, que se puede hacer avanzar cuando se considera que una situación es favorable (y sólo es favorable en la medida en que esta fuerza existe y está llena de ardor combativo); por esto, la tarea esencial es la de procurar sistemática y pacientemente formar, desarrollar, hacer cada vez más homogénea, más compacta y más consciente de sí misma esta fuerza [es decir, el partido]” (Gramsci, La política y el Estado moderno, pp. 116-7).

En síntesis: el análisis de la correlación de fuerzas sería “muerto”, pedante, pasivo, si no tomara en consideración que el partido es, debe ser, un factor fundamental en dicha correlación de fuerzas; el factor que puede terminar inclinando la balanza; el que munido de una política correcta, y apoyándose en un determinado “paralelogramo de fuerzas”, puede mover montañas.

La figura del “paralelogramo de fuerzas” nos fue sugerida por la carta de Engels a José Bloch (1890). Engels colocaba dicho paralelogramo como subproducto de determinaciones puramente “objetivas”. Sin embargo, a la cabeza de dicho “paralelogramo” se puede y debe colocar el partido para irrumpir en la historia: romper la inercia con el plus “subjetivo” que añade el partido: “(…) la historia se hace de tal modo, que el resultado final siempre deriva de los conflictos entre muchas voluntades individuales, cada una de las cuales, a su vez, es lo que es por efecto de una multitud de condiciones especiales de vida; son, pues, innumerables fuerzas que se entrecruzan las unas con las otras, un grupo infinito de paralelogramos de fuerzas, de las que surge una resultante -el acontecimiento histórico- (…)”.

El partido que sepa colocarse a la cabeza de dicho “paralelogramo”, que haya logrado construirse, que sepa hacer pesar fuerzas materiales en dicho punto decisivo, podrá mover montañas: romper el círculo infernal del “eterno retorno de lo mismo” abriendo una nueva historia.

Bibliografía

AAVV, Clausewitz en el pensamiento marxista, Pasado y Presente.

Darío de Benedetti, La teoría militar entre la Kriegsideologie y el Modernismo Reaccionario, Cuadernos de Marte, mayo 2010.

Daniel Bensaïd, La politique comme art stratégique, Archives personnelles, Âout 2007, npa2009.org.

Antonio Gramsci, La política y el Estado moderno, Planeta-Agostini, Barcelona, 1985.

León Trotsky, Lecciones de Octubre, Kislovodsk, 15 de septiembre de 1924, Marxist Internet Archive.

José Fernández Vega, Carl von Clausewitz. Guerra, política y filosofía, Editorial Almagesto, Buenos Aires, 1993.

[1] De Lenin se conoce un cuaderno de comentarios sobre De la Guerra; Trotsky “mechó” muchas de sus reflexiones estratégicas con referencias al teórico alemán, amén de tener sus propios Escritos militares.

[2] Ver nuestro texto Causas y consecuencias del triunfo de la URSS sobre el nazismo, en www.socialismo-o-barbarie.org.

[3] Tujachevsky estaba enrolado en la fallida “teoría de la ofensiva”. Trotsky estaba en contra de la misma: la condenaba por rígida, militarista y ultraizquierdista. Ver las Antinomias de Antonio Gramsci (un valioso texto del marxista inglés Perry Anderson de los años 70).

[4] En este caso se dio una sorprendente “inversión” (en relación a los errores) bajo el poder bolchevique: en general, fue Lenin el que dio en la tecla en las disputas con Trotsky. Pero en este caso las cosas se dieron invertidas: mientras Lenin se arremolinaba entusiasta sobre los mapas siguiendo la ofensiva, Trotsky manifestaba sus reservas.

[5] Ver al respecto nuestros textos sobre el bolchevismo en el poder.

[6] Ver al respecto El último combate de Lenin de Moshe Lewin.

[7] En todo caso, el siglo XX ha dado lugar a un sinnúmero de ricas experiencias militares en el terreno de la revolución, las que requieren de un estudio ulterior.

00:23 Publié dans Histoire, Militaria, Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : marxisme, marxisme révolutionnaire, clausewitz, guerre, guerre révolutionnaire, allemagne, prusse, histoire, théorie politique, politologie, sciences politiques |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

16:08 Publié dans Actualité | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, surveillance, big brother, censure, totalitarisme, police de la pensée |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

16:00 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes, Entretiens | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : politique internationale, igor dodon, moldavie, europe, affaires européennes, actualité, entretien |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

par Nicolas Bonnal

Ex; http://www.dedefensa.org

Tout le monde a oublié Henri Lefebvre et je pensais que finalement il vaut mieux être diabolisé, dans ce pays de Javert, de flics de la pensée, qu’oublié. Tous les bons penseurs, de gauche ou marxistes, sont oubliés quand les réactionnaires, fascistes, antisémites, nazis sont constamment rappelés à notre bonne vindicte. Se rappeler comment on parle de Céline, Barrès, Maurras ces jours-ci… même quand ils disent la même chose qu’Henri Lefebvre ou Karl Marx (oui je sais, cent millions de morts communistes, ce n’est pas comme le capitalisme, les démocraties ou les Américains qui n’ont jamais tué personne, Dresde et Hiroshima étant transmuées en couveuses par la doxa historique).

Tout le monde a oublié Henri Lefebvre et je pensais que finalement il vaut mieux être diabolisé, dans ce pays de Javert, de flics de la pensée, qu’oublié. Tous les bons penseurs, de gauche ou marxistes, sont oubliés quand les réactionnaires, fascistes, antisémites, nazis sont constamment rappelés à notre bonne vindicte. Se rappeler comment on parle de Céline, Barrès, Maurras ces jours-ci… même quand ils disent la même chose qu’Henri Lefebvre ou Karl Marx (oui je sais, cent millions de morts communistes, ce n’est pas comme le capitalisme, les démocraties ou les Américains qui n’ont jamais tué personne, Dresde et Hiroshima étant transmuées en couveuses par la doxa historique).

Un peu de Philippe Muray pour comprendre tout cela – cet oubli ou cette diabolisation de tout le monde :

« Ce magma, pour avoir encore une ombre de définition, ne peut plus compter que sur ses ennemis, mais il est obligé de les inventer, tant la terreur naturelle qu’il répand autour de lui a rapidement anéanti toute opposition comme toute mémoire. »

J’avais découvert Henri Lefebvre grâce à Guy Debord qui, lui, est diabolisé pour théorie de la conspiration maintenant ! Sociologue et philosophe, membre du PCF, Lefebvre a attaqué la vie quotidienne, la vie ordinaire après la Guerre, premier marxiste-communiste à prendre en compte la médiocrité de la vie moderne à la même époque qu’Henri de man (je sais, merci, fasciste-nazi-réac-technocrate vichyste etc.). Le plus fort est que Lefebvre attaque le modèle soviétique qui débouchait à la même époque sur le même style de vie un peu nul, les grands ensembles, le métro-boulot-dodo, le cinoche…

J’ai déjà évoqué Henri de Man dans mon livre sur la Fin de l’Histoire. Un bel extrait bien guénonien sans le vouloir :

« Tous les habitants de ces maisons particulières écoutaient en même temps la même retransmission. Je fus pris de cette angoisse … Aujourd'hui ce sont les informations qui jouent ce rôle par la manière dont elles sont choisies et présentées, par la répétition constante des mêmes formules et surtout par la force suggestive concentrée dans les titres et les manchettes. »

C’est dans l’ère des masses. On peut rajouter ce peu affriolant passage :

C’est dans l’ère des masses. On peut rajouter ce peu affriolant passage :

« L'expression sociologique de cette vérité est le sentiment de nullité qui s'empare de l'homme d'aujourd'hui lorsqu'il comprend quelle est sa solitude, son abandon, son impuissance en présence des forces anonymes qui poussent l'énorme machine sociale vers un but inconnu. Déracinés, déshumanisés, dispersés, les hommes de notre époque se trouvent, comme la terre dans l'univers copernicien, arrachés à leur axe et, de ce fait, privés de leur équilibre. »

Lefebvre dans un livre parfois ennuyeux et vieilli hélas (le jargon marxiste des sixties…) dénonce aussi cet avènement guénonien de l’homme du règne de la quantité. Il se moque des réactionnaires, mais il est bien obligé de penser comme eux (et eux ne seront pas oubliés, lui oui !) :

« Le pittoresque disparaît avec une rapidité qui n’alimente que trop bien les déclarations et les lamentations des réactionnaires…. »

Ici deux remarques, Herr professeur : un, le « pittoresque » comme vous dites c’est la réalité du paysage ancestral, traditionnel saboté, pollué et remplacé, ou recyclé en cuvette pour touristes sous forme de « vieille ville ». Deux, les chrétiens révoltés qui dénoncent cette involution dès le dix-neuvième ne sont pas des réacs sociologiques, pas plus que William Morris ou Chesterton ensuite.

Henri Lefebvre poursuit, cette fois magnifiquement :

« Là où les peuples se libèrent convulsivement des vieilles oppressions (nota : les oppressions coloniales n’étaient pas vieilles et furent remplacées par des oppressions bureaucratiques ou staliniennes pires encore, lisez Jacob Burckhardt), ils sacrifient certaines formes de vie qui eurent longtemps grandeur – et beauté. »

Et là il enfonce le clou (visitez les villes industrielles marxistes pour vous en convaincre :

« Les pays attardés qui avancent produisent la laideur, la platitude, la médiocrité comme un progrès. Et les pays avancés qui ont connu toutes les grandeurs de l’histoire produisent la platitude comme une inévitable prolifération. »

Les pays comme la Chine qui ont renoncé au marxisme orthodoxe aujourd’hui avec un milliard de masques sur la gueule, de l’eau polluée pour 200 millions de personnes et des tours à n’en plus finir à vingt mille du mètre. Cherchez alors le progrès depuis Marco Polo…

Les pays comme la Chine qui ont renoncé au marxisme orthodoxe aujourd’hui avec un milliard de masques sur la gueule, de l’eau polluée pour 200 millions de personnes et des tours à n’en plus finir à vingt mille du mètre. Cherchez alors le progrès depuis Marco Polo…

Matérialiste, Lefebvre évoque ensuite l’appauvrissement du quotidien, la fin des fêtes païennes-folkloriques (j’ai évoqué ce curieux retour du refoulé dans mon livre sur le folklore slave et le cinéma soviétique) et il regrette même son église enracinée d’antan (s’il voyait aujourd’hui ce que Bergoglio et les conciliaires en ont fait…). C’est la fameuse apostrophe de Lefebvre à son Eglise :

« Eglise, sainte Eglise, après avoir échappé à ton emprise, pendant longtemps je me suis demandé d’où te venait ta puissance. »

Eh oui cette magie des siècles enracinés eut la vie dure.

Je vous laisse découvrir cet auteur et ce livre car je n’ai pas la force d’en écrire plus ; lui non plus n’est pas arrivé avec le panier à solutions rempli…

Penseur du crépuscule marxiste, Lefebvre m’envoûte comme son église parfois. Comme disait le penseur grec marxiste Kostas Papaioannou, « le capitalisme c’est l’exploitation de l’homme par l’homme, et le marxisme le contraire » ! De quoi relire une petite révolte contre le monde moderne !

La révolution ? Le grand chambardement ? Sous les pavés la plage privatisée par les collègues de Cohn-Bendit ? Je laisserai conclure Henri Lefebvre :

« En 1917 comme en 1789, les révolutionnaires crurent entrer de plain-pied dans une autre monde, entièrement nouveau. Ils passaient du despotisme à la liberté, du capitalisme au communisme. A leur signal la vie allait changer comme un décor de théâtre. Aujourd’hui, nous savons que la vie n’est jamais simple. »

Et comme je disais que nos cathos réacs étaient les plus forts :

« La révolution… crée le genre d’homme qui lui sont nécessaires, elle développe cette race nouvelle, la nourrit d'abord en secret dans son sein, puis la produit au grand jour à mesure qu'elle prend des forces, la pousse, la case, la protège, lui assure la victoire sur tous les autres types sociaux. L'homme impersonnel, l’homme en soi, dont rêvaient les idéologues de 1789, est venu au monde : il se multiplie sous nos yeux, il n'y en aura bientôt plus d’autre ; c'est le rond-de-cuir incolore, juste assez instruit pour être « philosophe », juste assez actif pour être intrigant, bon à tout, parce que partout on peut obéir à un mot d'ordre, toucher un traitement et ne rien faire – fonctionnaire du gouvernement officiel - ou mieux, esclave du gouvernement officieux, de cette immense administration secrète qui a peut-être plus d'agents et noircit plus de paperasses que l'autre. »

« La révolution… crée le genre d’homme qui lui sont nécessaires, elle développe cette race nouvelle, la nourrit d'abord en secret dans son sein, puis la produit au grand jour à mesure qu'elle prend des forces, la pousse, la case, la protège, lui assure la victoire sur tous les autres types sociaux. L'homme impersonnel, l’homme en soi, dont rêvaient les idéologues de 1789, est venu au monde : il se multiplie sous nos yeux, il n'y en aura bientôt plus d’autre ; c'est le rond-de-cuir incolore, juste assez instruit pour être « philosophe », juste assez actif pour être intrigant, bon à tout, parce que partout on peut obéir à un mot d'ordre, toucher un traitement et ne rien faire – fonctionnaire du gouvernement officiel - ou mieux, esclave du gouvernement officieux, de cette immense administration secrète qui a peut-être plus d'agents et noircit plus de paperasses que l'autre. »

C’était l’appel de Cochin, le vrai…

Henri Lefebvre – critique de la vie quotidienne, éditions de l’Arche

Henri de Man – L’ère des masses

René Guénon – la crise du monde moderne ; le règne de la quantité et les signes des temps

Chesterton – Orthodoxie ; hérétiques (Gutenberg.org)

Cochin – La révolution et la libre pensée

Nicolas Bonnal – Chroniques sur la fin de l’histoire ; le cinéma soviétique et le folklore slave ; Céline, le pacifiste enragé

Julius Evola – révolte contre le monde moderne

14:57 Publié dans Philosophie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : nicolas bonnal, philosophie, marxisme, henri lefebvre, vie quotidienne, philosophie politique, théorie politique, politologie, sciences politiques |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

par Jean-Paul Baquiast

Ex: http://www.europesolidaire.eu

On a même parlé d'un nouveau Tigre Asiatique. Le système politique demeure cependant autoritaire, le Parti communiste vietnamien gouvernant seul. Voir https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vi%C3%AAt_Nam

Rappelons qu'après la guerre dite d'Indochine, perdue en fait par les Français lors de la bataille de Diên Biên Phu, la France a renoncé à poursuivre un conflit trop éloigné d'elle pour être gagnable. Lors des accords de Genève de 1954, négocié par Pierre Mendès-France pour le compte de la France, celle-ci a reconnu l'indépendance du pays.

Mais ce faisant elle a ouvert grand la porte aux Américains, qui ne voulaient pas que la Chine et derrière elle la Russie, ne fasse du Viet Nam un pays communiste. Une seconde guerre du Viet Nam en a résulté. Elle a opposé, de 1955 à 1975, d'une part la République démocratique du Viet Nam dit aussi Nord Viet Nam dont l'armée, dite Populaire vietnamienne a été soutenue matériellement et militairement par la Chine et la Russie soviétique - et d'autre part la République du Viet Nam (ou Sud Viet Nam), massivement représentée militairement par les États-Unis appuyés par plusieurs alliés (Australie, Corée du Sud, Thaïlande, Philippine). Un mouvement insurrectionnel d'inspiration communiste, le Front national de libération du Sud Viet Nam (dit Viet Cong) a par ailleurs combattu de l'intérieur le Sud-Viet Nam.

En 1964, la résolution dite du golfe du Tonkin a donné au président des États-Unis la mission de prendre en mains militairement le Viet Nam. L'intervention américaine a ravagé les infrastructures et l'environnement du Viet Nam, avec notamment des moyens chimiques constituant de véritables crimes de guerre . Mais malgré les moyens militaires considérables engagés, l'Amérique a échoué à mettre un terme à l'insurrection.

A la fin des années 1960, la guerre était devenue de plus en plus impopulaire aux États-Unis. Des mouvements d'opposition de plus en plus violents – les seuls qu'aient jamais connu et que connaitront jamais sans doute les Etats-Unis - ont obligé le gouvernement américain à reconnaître son incapacité à gagner la guerre. De longues négociations ont abouti en 1973 aux accords de paix de Paris et au retrait américain. Deux ans plus tard, le Nord Viet Nam a mené une offensive victorieuse contre le Sud. Le Viet Nam, désormais entièrement sous contrôle communiste, a été réunifié en 1976.

À partir de la seconde moitié des années 1980, et après la mort du dirigeant conservateur Lê Duan, le Viet Nam a entamé une sorte de perestroïka sur le modèle russe. Il a libéralisé son économie, s'affirmant progressivement comme un pays émergent dynamique. Le système politique demeure cependant autoritaire, le Parti communiste vietnamien gouvernant en tant que parti unique.

Le Viet Nam entre la Russie et les Etats-Unis

Aujourd'hui, un point important en termes de politique internationale est le poids que peut avoir le Viet Nam dans les rapports de plus en plus conflictuels entre la Russie et les Etats-Unis, du fait d'ailleurs essentiellement de ce dernier pays.

Dans les dernières décennies, le Viet Nam, considéré initialement comme un des pays les plus pauvres d'Asie, s'est rapproché économiquement de Hong Kong, de Singapour, de Taiwan et dans une certaine mesure de la Corée du Sud. Les éléments de marché que le gouvernement avait introduit à la fin des années 1980, sans abandonner le principe d'une économie socialiste partiellement dirigée, lui ont procuré une base industrielle, énergétique, scientifique et agricole lui permettant de subvenir à ses propres besoins et de se donner une balance commerciale et touristique favorable. Il a encouragé également les investissements étrangers, inévitablement américains mais aussi chinois.

Le Viet Nam est désormais un membre influent de l'ASEAN ou Association des nations de l'Asie du Sud-Est https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Association_des_nations_de_... . Celle-ci était censée à sa fondation s'opposer aux pays dits communistes, mais la Chine y joue désormais un rôle important. Face au déclin de l'influence américaines surtout au poids que prennent désormais dans la région les grands programmes chinois tels que l'OBOR (One Belt, One Road). Le Viet Nam est intéressé par certains des projets de l'OBOR, notamment la voie ferrée Kunming Singapour qui devrait traverser l'ensemble de la péninsule.

Cependant, Hanoï n'entend pas devenir une sorte de satellite de la Chine dont il se distingue par ailleurs sur de nombreux plans, notamment culturel et ethnique. Il entretient des rapports fructueux avec le Laos son voisin où son armée avait joué un rôle important dans la guerre civile laotienne de 1968-1973. De même, il coopère étroitement avec son autre voisin le Cambodge. Il existe deux organisations en ce sens, le Committee of the Vietnam-Laos Solidarity and Friendship et le Vietnam-Cambodia Solidarity and Friendship.

Mais pour équilibrer le poids de la Chine, c'est surtout sur la Russie que le Viet Nam compte désormais. La Russie a bien compris le poids du Viet Nam et de ses voisins et compte de son côté en profiter. La Russie communiste avait, tout autant sinon plus que la Chine, soutenu le Viet Nam dans la seconde guerre d'Indochine avec l'Amérique. Après la chute de l'URSS, les deux pays avaient signé en 1994 un Traité d'Amitié. Depuis, ils ont développé leur coopération dans les domaines économique, politique et militaire. En 2012, ils ont publié une Déclaration Commune de Partenariat Stratégique.

Aujourd'hui la Russie fournit des armements modernes à l'armée et à la marine Vietnamiennes dont elle entraine des contingents sur son territoire. Tout aussi important est le travail en commun sur les questions financières, d'extraction pétrolière et gazière comme dans des projets de centrales nucléaires. En 2015, leurs échanges ont atteint une valeur de 4 milliards de dollars. Ce niveau s'est accru de 25% en 2016. Il est positif en faveur de la Russie d'environ 1 milliard.

Par ailleurs, en 2015, un accord de Libre-Echange a été signé entre le Viet Nam et l'organisme dit Union Economique Eurasiatique https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Union_%C3%A9conomique_euras... où la Russie joue un rôle dominant.

Ceci ne veut pas dire que le Viet Nam ne tienne pas à conserver de bonnes relations diplomatiques et économiques avec les Etats-Unis. Mais manifestement, il donnera si cela s'imposait la préférence à la Russie. Vladimir Poutine le sait mais n'en abuse pas.

14:39 Publié dans Actualité, Géopolitique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, politique internationale, géopolitique, vietnam, asie, affaires asiatiques, russie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

It is quite common in our sphere for the focus of analyses to rest on the functionality and the securing of power mechanisms in a society, both inside and outside of government. The interpretation of these mechanisms and how they developed are generally elucidated through the lens of certain macrohistorical events and trends which have existed in the West for several centuries. However, history does not exist in a vacuum, and a thorough analysis of these events cannot neglect to consider the characteristics of the “human material” involved in these trends. Doing so will leave explanatory power on the table that could be applied to understand these events more fully, and thus to learn more precise lessons from them.

One of our fundamental goals is to seek to restore a socially stable order. To this end, there a number of critiques of democracy and other factors which divide power and create unstable social and political circumstances. To fully encompass this goal, it is necessary to take into account sociological and ethnographic factors which are not always reflected in purely formalistic analyses. I would argue that one of the primary factors of interest should be that of ethnicity and its interplay both within and between groups.

First, some definitions are in order. “Ethnicity” is a term that primarily refers to commonalities shared within human groups, which serve to define the “in-group” over and against “out-groups.” Ethnicities center around “ethnic markers,” such as language, religion, morals, traditions and customs, patterns of daily living, and so forth. Often, ethnicity is delineated through the use of various “ideological” indicators (e.g. common mythology, common descent from an eponymous ancestor), the acceptance of which helps to determine group membership. While phenotype can be included in the set of markers, it is not usually a primary determinant and is most often not what principally defines an ethnie.

It is true that members of the same ethnie will almost always share similar phenotypic expressions (which are not limited merely to skin color, however). It is likewise true that phenotypic distinctions can serve as “in/out-group” markers, especially across metaethnic faultlines. Nevertheless, “race” as a modernistic, purely biological and genetic concept, is not what is being discussed here. Rather, commonality of custom, language, religion, and psychology are at issue, and these have served for so long to define differing groups of people that they are the very quintessence of “tradition.”

It is widely recognized within the social sciences that shared ethnicity is one of the single most powerful organizing principles that exists. Ethnicity has played a role in helping to be organize and distinguish between groups from our tribal beginnings. It is something that has been hardwired into the human psyche for thousands of years, dating back to even before the rise of our first truly agrarian civilizations.

The reason all of this is important hearkens back to what was said earlier about the goal of reestablishing a stable social order. It is through the concept of ethnicity that “collective solidarity” (closely related to the Khaldunian concept of asabiyyah in agrarian societies) is primarily expressed. Collective solidarity is a (potentially) quantifiable measure of the capacity for the members of a social body to work together solidaristically towards the achievement of common goals and purposes. It is well-known that collective solidarity is much more easily achieved within groups of people who more readily identify with each other as a result of shared ethnicity. Conversely, closely proximate diversity tends to breed mistrust and a lower willingness to work together for a common good. This solidaristic behavior with co-ethnics is much stronger than for artificial groupings centered around shared economic interest or hobbies, such as corporations and fraternal organizations.

Those concerned with true social stability must work toward the establishment of rational ethnostructures that will facilitate, rather than hinder, collective solidarity. This implies a rejection of abstract civic nationalism and the “multicultural” state, as well as rejection of the sort of immigration policies and structural power-distributing institutions which would encourage multiculturalism. Keep in mind, of course, that empires in which an aristoclade has established imperial control over its neighbors, but is not actively trying to co-mingle them, do not necessarily come within the purview of this analysis.

The power of collective solidarity can easily be seen in the modern Western experience. Certainly, collective solidarity is something that waxes or wanes within individual ethnies over time. Collective solidarity will increase when the core elite element within an ethnie exhibits unity among itself and shares goals and ideology, which it then leads its co-ethnic commons to act upon. Usually, collective solidarity increases due to several collaborating factors, such as a shared struggle against an external enemy, a low ratio of population density to shared resources (which reduces intragroup competition), and the proximity of vastly different ethnic groups across a shared border.

Conversely, collective solidarity declines when an ethnie’s elite core is degenerate, divided, or no longer sees itself as sharing a common destiny, identity, and purpose with its co-ethnic commons.

The rise of the West coincided with a high level of collective solidarity within the various Western ethnies. Each nation shared a unity of purpose and a willingness to work together for common goals (usually national expansion or other forms of national glory). This unity was shared between the elite and common elements, and this was true even given the greater general tendency towards individualism found among northwestern European populations (but which also existed among other Europeans, as well).

The decline of the West has coincided with a palpable decline in collective solidarity among Western ethnies. There is an increasing ideological and cultural gap between our ethnic elites and the rest. This is combined with the presence of an alloethnic elite, which has suborned the loyalties of Western ethnic elites. This occurred because Jews tend to exhibit much greater in-group cohesion (i.e. higher collective solidarity) which allows them to out-compete native Western elites, who grew complacent and were already waning in their sense of solidarity with their own co-ethnic commons during the 20th century.

It should go without saying that groups with higher collective solidarity will nearly always be able to outstrip those without it.

The encouragement of multiculturalism, mass third world immigration, and other trust-destroying phenomena has been a successful strategy used by alloethnic leaders in the West to further destroy Western collective solidarity and allow victory in ethnic conflicts between alloethnic and European/American ethnic elites. Even if these phenomena were entirely native in origin, mass immigration would still be destroying Western collective solidarity, resulting in the atomization and weakening of our societies. Individualism only really has the ability to thrive when collective solidarities are worn down and broken.

Thus, it’s important to support efforts and methods for increasing collective solidarity among Western ethnies. As such, we must find (and implement) ways to increase ethnic identification among Western populations. One strategy for this is to encourage the expression of traditional ethnic markets such as Christianity, European heritage and traditions, the revivification of local languages, and the like. Coupled with this, however, must be a concerted effort to “re-elitify” these markets, so that they not only find wide expression among the ethnic commons of the various Western nations, but are also readopted by the elites, thus unifying the sense of collective purpose in our ethnies.

Doing this must obviously be coupled with the pursuit of technical methods for obtaining and maintaining formal structural power, which has been a primary interest in our sphere. Hence, the two concepts – structural formalism and ethnocollective solidarity – can and must work in tandem. Any Restoration that might take place and institute a formal mechanism for the holding and use of power will be hollow if it is not coupled with the support structure provided by a unified ethnic solidarity.

00:11 Publié dans Définitions, Ethnologie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : ethnie, ethnicité, définition |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

par Jean Paul Baquiast

Ex: http://www.europesolidaire.eu

http://www.europesolidaire.eu/article.php?article_id=2892...=,

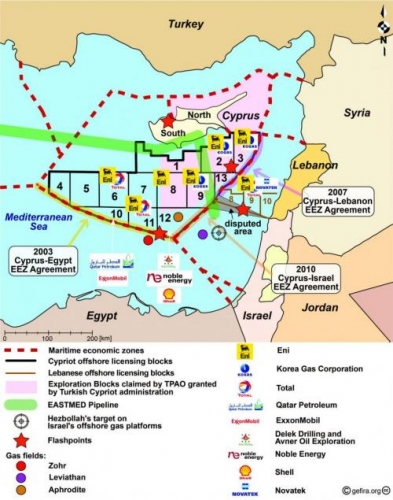

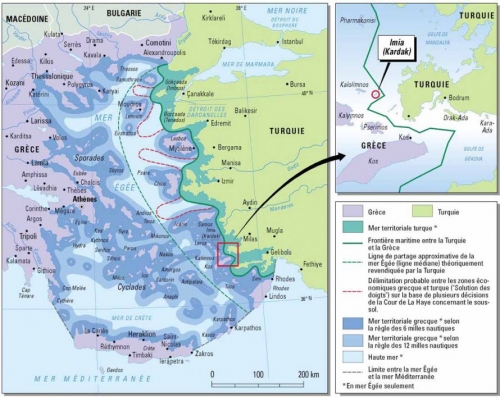

Aujourd'hui la Turquie a décidé d'entrer dans le jeu. Elle est le seul pays à reconnaitre l'autoproclamée République Turque de Chypre du Nord qui revendique une partie de l'ile, face à la République de Chypre, seule à être admise à l'ONU. Les deux républiques se partagent la capitale, Nicosie https://fr.wikipedia.org/wiki/Chypre_(%C3%AEle)

La Turquie affirme dorénavant que les activités relatives à l'exploration des champs de gaz situés dans la zone maritime de l'ile de Chypre relèvent en fait de la souveraineté de République Turque de Chypre du Nord, autrement dit de son influence. Elle n'avait pas précédemment reconnu la validité des accords entre la République de Chypre et d'autres pays, notamment l'Italie, pour l'exploration des eux relevant de sa zone économique exclusive.

Ankara y défend les intérêts de la Turkish Petroleum Corporation (TPAO) qui se veut seule en droit d'explorer cette zone, au nom d'accords avec la République Turque de Chypre du Nord. Le président Erdogan vient de prévenir la République de Chypre (du Sud) et divers compagnies pétrolières, dont l'ENI italienne, que la violation des intérêts turcs auraient de « graves conséquences ». Sans attendre, mi-février 2018, des unités turques ont bloqué un navire d'exploration le Saipem, explorant pour le compte de l'ENI. Par ailleurs, peu après, un garde-côte turc a abordé délibérément un aviso grec en Mer Egée. L'Italie en réponse n'a pas tardé à envoyer un navire militaire dans la zone.

Il y a tout lieu de penser que si un arbitrage international s'organisait, les Etats européens soutiendraient Chypre, la Russie soutenant la Turquie, malgré leurs différents actuels à Afrin

Le projet de gazoduc EastMed

La position respective des protagonistes sera également fonction du développement du projet de gazoduc EastMed ou Eastern Mediterranean Gas Pipeline https://ec.europa.eu/inea/en/connecting-europe-facility/c.... Celui-ci, visant à apporter du gaz de la Méditerranée à la Grèce via Chypre et la Crète, affaiblirait le rôle de transit de la Turquie prévu dans le projet de pipe TANAP, dit aussi pipeline Transanatolien http://www.tanap.com/tanap-project/why-tanap/ Il devra transporter du gaz de la Caspienne produit en Azerbaidjan vers la Turquie et ensuite l'Europe.

Ajoutons qu'un autre conflit se prépare, celui-ci entre la Turquie et l'Egypte, a propos du riche champ gazier dit Zohr découvert en 2015. Ankara ne reconnait pas les accords signés entre Chypre et l'Egypte en 2003 qui attribuaient au Caire une souveraineté exclusive sur les eaux frontières entre le Caire et Nicosie. En fonction de cet accord, l'Egypte a prévenu la Turquie en février 2018 qu'elle n'accepterait pas de prétentions turques relative au gisement du Zohr. Mais que signifie « ne pas accepter » ?

Cependant, comme l'indiquait notre article précité du 01/02, les futurs conflits envisagés ci-dessus n'auront pas l'intensité de ceux actuellement craints entre Israël et le Liban à propos de l'exploration des zones dites Blocks 8, 9 et 10 dont Israël refuse la concession par le Liban à l'ENI, à Total et au russe Novatek. Or quand Israël défend des intérêts de cette nature, il ne le fait pas seulement par la voie de négociations. Il menace d'interventions militaires dont chacun le sait parfaitement capable.

Comme quoi, il apparaît que les gisements gaziers de la Méditerranée orientale, loin d'apporter la prospérité aux pays concernés, risquent de provoquer des confrontations militaires entre les Etats Européens, la Turquie, Israël et en arrière plan la Russie, les Etats-Unis et l'Iran. Le contraire, il est vrai, aurait surpris.

11:11 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes, Géopolitique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : chypre, méditerranée, méditerranée orientale, hydrocarbures, pétrole, gaz, géopolitique, politique internationale |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Don’t tell the Iran hawks in D.C., isolating Iran won’t work. Iranian President Hassan Rouhani met with his Indian counterpart Narendra Modi this week and the two signed a multitude of agreements.

The most important of which is India’s leasing of part of the Iranian port of Chabahar on the Gulf of Oman. This deal further strengthens India’s ability to access central Asian markets while bypassing the Pakistani port at Gwadar, now under renovation by China as part of CPEC – China Pakistan Economic Corridor.

CPEC is part of China’s far bigger One Belt, One Road Initiative (OBOR), its ambitious plan to link the Far East with Western Europe and everyone else in between. OBOR has dozens of moving parts with its current focus on upgrading the transport infrastructure of India’s rival Pakistan while Russia works with Iran on upgrading its rail lines across its vast central plateaus as well as those moving south into Iran.

India is investing in Iran’s rails starting at Chabahar and moving north.

Just Part of the Much-Needed Rail Upgrade Iran Needs to Connect it to India

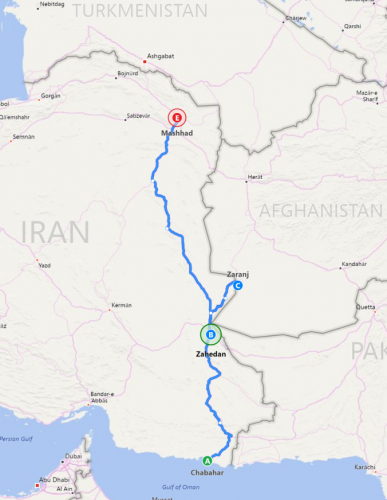

Chabahar has long been a development goal for Russia, Iran and India. The North-South Transport Corridor (NSTC) was put on paper way back when Putin first took office (2002). And various parts of it have been completed. The full rail route linking Chabahar into the rest of Iran’s rail network, however, has not been completed.

The first leg, to the eastern city of Zahedan is complete and the next leg will take it to Mashhad, near the Turkmenistan border. These two cities are crucial to India finding ways into Central Asia while not looking like they are partaking in OBOR.

Also, from Zahedan, work can now start on the 160+ mile line to Zaranj, Afghanistan.

The recent deal between Iran and India for engines and railcars to run on this line underscores these developments. So, today’s announcements are the next logical step.

As these rail projects get completed the geopolitical imperatives for the U.S. and it’s anti-Iranian echo chamber become more actute. India, especially under Modi, has been trying to walk a fine line between doing what is obviously in its long-term best interest, deepening its ties with Iran, while doing so without incurring the wrath of Washington D.C.

India is trapped between Iran to the west and China to the east when it comes to the U.S.’s central Asian policy of sowing chaos to keep everyone down, otherwise known as the Brzezinski Doctrine.

India has to choose its own path towards central Asian integration while nominally rejecting OBOR. It was one of the few countries to not send a high-ranking government official to last year’s massive OBOR Conference along with the U.S.

So, it virtue signals that it won’t work with China and Pakistan. It’s easy to do since these are both open wounds on a number of fronts. While at the same time making multi-billion investments into Iran’s infrastructure to open up freight trade and energy supply for itself.

All of which, by the way, materially helps both China’s and Pakistan’s ambitions int the region.

So much of the NTSC’s slow development can be traced to the patchwork of economic sanctions placed on both Russia and Iran by the U.S. over the past ten years. These have forced countries and companies to invest capital inefficiently to avoid running afoul of the U.S.

The current deals signed by Rouhani and Modi will be paid for directly in Indian rupees. This is to ensure that the money can actually be used in case President Trump decertifies the JCPOA and slaps new sanctions on Iran, kicking it, again, out of the SWIFT international payment system.

Given the currency instability in Iran, getting hold of rupees is a win. But, looking at the rupee as a relatively ‘hard’ currency should tell you just how difficult it was for Iran to function without access to SWIFT from 2012 to 2015.

Remember, that without India paying for Iranian oil in everything from washing machines to gold (laundered through Turkish banks), Iran would not have survived that period.