Perceptive Australians and New Zealanders are fortunate in having in New Dawn a medium that looks at history from breadth and depth. Hence, New Dawn has long viewed Russia as the place where great historical forces will unfold.

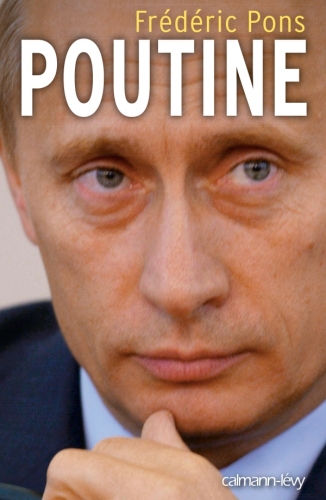

Despite the misgivings of some Russian patriots, Vladimir Putin has emerged as a new Russian strong-man. New Dawn saw the possibilities for Russia under Putin at the earliest days of his political ascent. For one commentator in New Dawn, the rise of Putin had mystical implications that could impact on the world in an epochal way: Putin’s inauguration as Prime Minister on 9 August 1999 occurred during the week of the solar eclipse and the planetary alignment of the Grand Cross, ‘a highly auspicious astrological event… traditionally held to be the end of an epoch’.[1]

MULTIPOLAR VS. UNIPOLAR WORLD

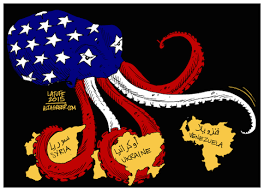

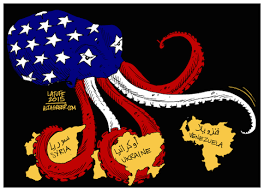

As New Dawn also reported at an early stage of Putin’s assumption to power, the new leader had no intention of continuing a process that had begun with Gorbachev: the integration of Russia into a world political and economic system, with its concomitant cultural degradation. New Dawn reported Venezuelan President Hugo Chavez predicting that the 21st century would be a multipolar world. What some important elements in US governing circles call the ‘new American century’[2] would be nothing of the kind, despite their increasingly aggressive efforts. Chavez, a leader of rare statesmanship, believed that this would be a century of power blocs.[3] Putin’s Russia has pursued the building of a ‘multipolar’ world.

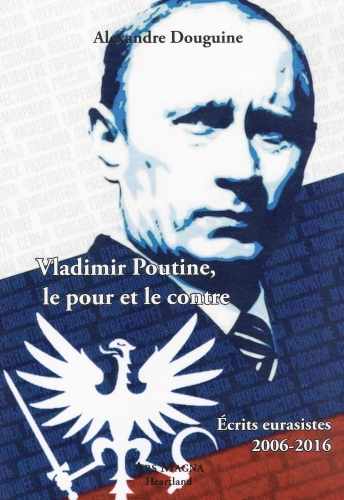

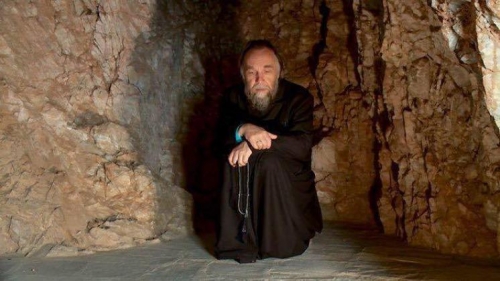

Multipolarity is a doctrine that permeates much of the academic and ruling elite of Russia. Its most well-known proponent is Dr Alexander Dugin, who heads the Centre for Conservative Studies, Sociology Department, at Moscow State University.[4] What Chavez was referring to as unified continental power blocs, Dugin refers to as ‘vectors’. I have elsewhere outlined Dugin’s doctrine, with a focus on how this might apply to Australasia,[5] although I do not see why Australia (and presumably New Zealand) should come under a ‘vector’ that is focused either on the USA or China, and believe that Dugin is being overly generous towards those two hegemonistic powers. More preferable is the vision of Dugin’s precursor, Jean Thiriart, a Belgian revolutionary geopolitical theorist who saw Euro-Russia (or ‘Euro-Soviet’, since the USSR was still intact) in alliance with a Latin American bloc (the vision had been promoted by his friend Juan Peron, and is still promoted by Bolivarian Venezuela), in opposition to US global ambitions.[6]

As for Dugin’s influence in Russia, two antagonistic academics lament of him: ‘The growing interest among political scientists and other observers in Dugin and his activities is the result of his recent evolution from a little-known marginal radical right-winger to a notable and seemingly influential figure within Russia’s mainstream’.[7]

As for Dugin’s influence in Russia, two antagonistic academics lament of him: ‘The growing interest among political scientists and other observers in Dugin and his activities is the result of his recent evolution from a little-known marginal radical right-winger to a notable and seemingly influential figure within Russia’s mainstream’.[7]

Dugin calls his geopolitical concept ‘Eurasianism’, writing of this:

‘In the broad sense the Eurasian Idea and even the Eurasian concept do not strictly correspond to the geopolitical boundaries of the Eurasian continent. The Eurasian Idea is a global-scale strategy that acknowledges the objectivity of globalisation and the termination of nation-states, but at the same time offers a different scenario of globalisation, which entails no unipolar world or united global government. Instead it offers several global zones (poles). The Eurasian Idea is an alternative or multipolar version of globalisation, but globalisation is the currently fundamental world process that is deciding the main vector of modern history’.[8]

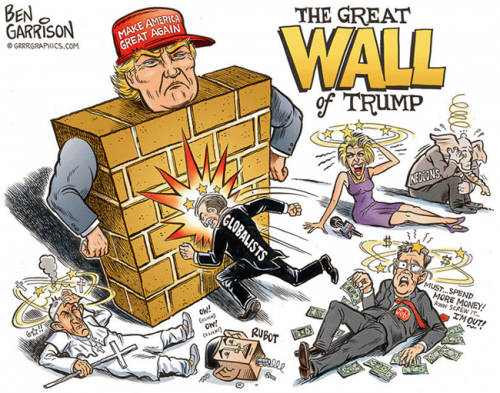

Hence, Dugin agrees that the days of petty states are numbered and were a manifestation of a phase of history. Dugin postulates therefore something beyond petty-statism, imperialism or globalism, power blocs based on organic geopolitical realties, although details should remain open to question. Such geopolitical thinking is very much to the fore in Russia, among the highest echelons of academia and politics. Putin’s Russia, like Stalin’s Russia, is problematic in regard to the ‘new world order’ that the globalists confidently thought would emerge under the interregnum of Gorbachev and Yeltsin. Like Stalin, who scotched globalist plans for a ‘new world order’ in the aftermath of World War II, Putin is an upstart in globalist eyes.

VLADIMIR PUTIN

One of the numerous globalist NGO’s directed at Russia, The Jamestown Foundation[9], offered several opinions in regard to the direction of Russia with Putin’s re-election in 2011. A major concern is whether Putin’s anti-American expressions during the elections were based on electoral rhetoric in drumming up Russians against an external enemy, or a genuinely held perception of the USA as intrinsically inimical to Russia. Certainly Putin would be naïve if he regards the USA as anything other than being committed to the subordination of Russia to economic predation and cultural decay. The USA has been the home-base for the destruction of Russia as a world power since Stalin’s rejection of the USA’s vision of the post-war world in 1945,[10] inaugurating the ‘Cold War’. The very fact of the existence of The Jamestown Foundation, among a gaggle of other NGOs whose board members often have close connections with US governmental agencies, including the military and intelligence,[11] indicates this.

Citing a report from Chattham House by James Nixey, entitled ‘Russia’s Geopolitical Compass’, Nixey points to four ‘geostrategic axes for Russia: the West, Russia’s many ‘souths’ – the Black Sea region and the Islamic world – Russia’s Far East and the Arctic North’. Nixey states that Russia no longer views the ‘West’[12]as all-powerful, and that Obama’s post-Bush so-called ‘Reset’ policy for rapprochement with Russia is ‘losing direction’. What is particularly interesting is that Nixey agrees with Sinologist Bobo Lo, Senior Research Fellow at the Centre for European Reform in London, who states ‘that Russia’s relations with China are nothing more than an “alliance of convenience” by which Russia seeks to leverage influence with the West to gain acceptance. In this context, China is only a “geopolitical counterweight to the West.”’[13]

Citing a report from Chattham House by James Nixey, entitled ‘Russia’s Geopolitical Compass’, Nixey points to four ‘geostrategic axes for Russia: the West, Russia’s many ‘souths’ – the Black Sea region and the Islamic world – Russia’s Far East and the Arctic North’. Nixey states that Russia no longer views the ‘West’[12]as all-powerful, and that Obama’s post-Bush so-called ‘Reset’ policy for rapprochement with Russia is ‘losing direction’. What is particularly interesting is that Nixey agrees with Sinologist Bobo Lo, Senior Research Fellow at the Centre for European Reform in London, who states ‘that Russia’s relations with China are nothing more than an “alliance of convenience” by which Russia seeks to leverage influence with the West to gain acceptance. In this context, China is only a “geopolitical counterweight to the West.”’[13]

This issue of Sino-Russian relations is vitally important, especially to Australians and New Zealanders, who have hitched their wagons to China’s star that is one day going to implode and fall.[14]

There are those both on the ‘fringes’ of politics and in influential positions who see Russia as an ally rather than as a threat to Europe, a united Europe. France having more than the usual number of geopolitical realists, has included a strong Russophile element that looked to Russia, including during its Soviet days, as a counterweight to US hegemony contrary to the propaganda of the Soviet bogeyman poised to ravish the Occident. One probably most immediately recalls the call of President Charles de Gaulle for a united Europe ‘from the Atlantic to the Urals’. The Jamestown Foundation’s article cites a view offered by Marc Rousset, a French historian and political analyst and author of La nouvelle Europe: Paris-Berlin-Moscou [The New Europe: Paris-Berlin-Moscow] (2009):

‘According to Rousset, Putin would bring “bravery, foresight and pragmatism” to Russian policy in the interest of creating a geopolitical order from the Atlantic to Vladivostok. Rousset emphasized that Putin is a European from St. Petersburg working toward closer ties among Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. His conception of a Eurasian union had the possibility of creating an imperial order to rival that of the American empire and the emerging new orders in China and India[15] (Rossiiskaia Gazeta, March 6). Rousset was quoted in November of last year as seeing the emergence of an axis of Paris, Berlin and Moscow being the answer to the present crisis in the Eurozone and the means to restore Europe’s position as a major player in the international system (Rossiiskaia Gazeta, November 17, 2011). Sergei Karganov answered that line of thought in December of last year by calling on Russia to turn away from Europe and make its future with a dynamic Asia-Pacific region led by China (Rossiiskaia Gazeta, December 28, 2011)’.[16]

‘According to Rousset, Putin would bring “bravery, foresight and pragmatism” to Russian policy in the interest of creating a geopolitical order from the Atlantic to Vladivostok. Rousset emphasized that Putin is a European from St. Petersburg working toward closer ties among Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. His conception of a Eurasian union had the possibility of creating an imperial order to rival that of the American empire and the emerging new orders in China and India[15] (Rossiiskaia Gazeta, March 6). Rousset was quoted in November of last year as seeing the emergence of an axis of Paris, Berlin and Moscow being the answer to the present crisis in the Eurozone and the means to restore Europe’s position as a major player in the international system (Rossiiskaia Gazeta, November 17, 2011). Sergei Karganov answered that line of thought in December of last year by calling on Russia to turn away from Europe and make its future with a dynamic Asia-Pacific region led by China (Rossiiskaia Gazeta, December 28, 2011)’.[16]

Rousset’s ideal is in my opinion the preferred. While Sergei Karganov[17] is in accord with the Dugin conception of ‘Eurasianism’ vis-à-vis Russia’s place with China in Asia, Dugin also sees Russia in alliance with united Europe, and her historical relationship with ‘Hindustan’.[18] Historically a Sino-Russian alliance is an aberration, as indicated by other geopolitical analysts such as Bobo Lo. Putin hopes to play the China card, a policy that the USA pursued during the 1970s against the USSR. However, there are more scenarios for geopolitical discord between Russia and China than what there ever have been and possibly ever will be between the much-hyped supposed rivalry between China and the USA. The deployment of the Russian military in the Far East indicates Putin’s realism on the issue.[19] Hopefully such manoeuvres are more reflective of Russian aims than Karganov’s ideal of a Sino-Russian partnership for the control of the Asia-Pacific region, a conception that seems more akin to Trilateralism.[20]

DUGIN’S ANALYSIS

Indicating the seriousness with which Alexander Dugin is taken by Russia’s friends and enemies alike, Kipp comments of Dugin’s reaction to the re-election of Putin:

‘In the aftermath of Putin’s election, Aleksandr Dugin, the chief ideologue of anti-Western Eurasianism, stated that Putin stood at a moment of strategic choice: embrace the liberalism and Westernism of Russia’s bourgeois elite or the nationalism of the Russian common folk – historically the victims of the corruption of Russia’s liberal elite, which champions Russia’s subservience to the West. Dugin wrote that by promoting a Eurasian Union, Putin had already spoken the word that defined his choice. This was the path to national revival and to an economy based upon the reconstruction of Russia’s defense sector. Dugin states: “Both sides want reforms from Putin but they desire direct opposites. The elites want democratization, modernization, liberalization and growing closer to the West. The people want the national idea, a firm hand, a strengthening of sovereignty, a great power state, paternalism and social justice.” This choice for Putin comes at a particularly critical moment, according to Dugin. The hegemony of the US and its allies is being tested in an emerging multi-polar world. The immediate challengers are Syria and Iran. But once those two states have been defeated by military intervention, Russia itself will have to face the threat of such intervention. “…after the prepared attacks on Syria and Iran, the logical next target will be Russia. Of course, Russia will not survive such a confrontation with the West alone’.[21]

However, China remains the thorny question among those who seek a revived Russia, with Dugin and his movement seeing China as a crucial ally,[22] while others see China as a future rival.[23]

THE ASSAULT ON RUSSIA

For those who see Russia and China as natural allies in a bloc that can thwart US-led globalisation, it might be instructive to consider Washington and Wall Street’s attitudes towards both over the decades. While some ‘neocon’ elements in the USA raise their voices against China’s aims, Rockefeller, Soros and others of the globalist elite have maintained a pro-China attitude. Globalist foreign policy luminaries such as Henry Kissinger and Zbigniew Brzezinski have seen Russia as the USA’s perennial obstacle to world hegemony while their attitudes towards China have been more generous, Rockefeller Trilateralism and Soros globalism seeing China as an essential partner in a ‘new world order’.[24] One might also consider the immense efforts of the USA to ‘contain’ Russia from the days of Stalin to the present,[25] and a comparative lack of action regarding China’s ambitions. Elsewhere I have written on this:

‘The Rockefeller dynasty has led the pro-China policy for decades. The “Pacific Asian Group” of David Rockefeller’s Trilateral Commission includes representatives from China. However, Rockefeller interests in China go back well prior to the Trilateral Commission, to the Asia Society. The Asia Center New York office states that John D. Rockefeller III founded the Society in 1956…[26]

US actions against Putin’s Russia remain as determined as those against the USSR during the Cold War. Dr Paul Craig Roberts, US Assistant Secretary of the Treasury under the Reagan Administration, has written of the subversion against Russia:

‘The Russian government has finally caught on that its political opposition is being financed by the US taxpayer-funded National Endowment for Democracy and other CIA/State Department fronts in an attempt to subvert the Russian government and install an American puppet state in the geographically largest country on earth, the one country with a nuclear arsenal sufficient to deter Washington’s aggression’.[27]

Roberts was referring to an Act passed by the Duma requiring the registration of NGOs receiving foreign funds, similar to the requirements of US laws that have long been in place. Roberts continued:

‘The Washington-funded Russian political opposition masquerades behind “human rights” and says it works to “open Russia.” What the disloyal and treasonous Washington-funded Russian “political opposition” means by “open Russia” is to open Russia for brainwashing by Western propaganda, to open Russia to economic plunder by the West, and to open Russia to having its domestic and foreign policies determined by Washington’.[28]

Globalists are aiming to deconstruct Russia as they did the USSR. Fortunately, Putin is no Gorbachev. His ambition seems to be that of leading a strong Russia, as distinct from Mikhail Gorbacehv’s ambition to become a globalist celebrity posturing on the world stage. When on his 80th birthday in 2011 Hollywood stars hosted a ‘gala celebration’ at the Royal Albert Hall, London, ABC News commented that the ‘movie stars, singers and politicians’ who turned out for the show, ‘underlined the celebrity status Mr Gorbachev enjoys in the West, where he is widely perceived as the man who freed Eastern Europe from Soviet rule and ended the Cold War’.[29] On the occasion of his birthday Gorbachev delivered what might be construed as an ultimatum to Putin on behalf of the globalist elite, ‘advising’ him ‘against running for a third term as president and warning about the dangers of Arab-style social revolt’.[30] As is now clear, those ‘Arab social revolts’, like the ‘colour revolutions’ in the former Soviet states, were stage-managed by the globalist NGOs.

The globalist think tanks are blatant in their intentions. The Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), opines that ‘Russia is heading in the wrong direction’.[31] One of the CFR recommendations is to interfere with the Russian political process, urging US Congress to fund opposition movements by increased funding for the Freedom Support Act, in this instance referring specifically to the 2007-2008 presidential elections.[32] Authors of the CFR report include Mark F Brzezinski, who served on the National Security Council as an adviser on Russian and Eurasian affairs under Clinton, as his father Zbigniew served in the Carter Administration; Antonia W Bouis, founding executive director of the Soros Foundations; James A Harmon, senior advisor to the Rothschild Group, et al. US ruling circles have a messianic mission to create a world revolution, and it is no surprise that the ideological foundations of the US ‘world revolution’ were developed by Russophobic Trotskyites during the Cold War.[33] The task of publicly announcing the post-Soviet world revolution was allotted to President George W Bush. Speaking before the National Endowment for Democracy in 2003, Bush stated that the war on Iraq was a continuation of a ‘world democratic revolution’ that started in the Soviet bloc: ‘The revolution under former president Ronald Reagan freed the people of Soviet-dominated Europe, he declared, and is destined now to liberate the Middle East as well’.[34]

The globalist think tanks are blatant in their intentions. The Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), opines that ‘Russia is heading in the wrong direction’.[31] One of the CFR recommendations is to interfere with the Russian political process, urging US Congress to fund opposition movements by increased funding for the Freedom Support Act, in this instance referring specifically to the 2007-2008 presidential elections.[32] Authors of the CFR report include Mark F Brzezinski, who served on the National Security Council as an adviser on Russian and Eurasian affairs under Clinton, as his father Zbigniew served in the Carter Administration; Antonia W Bouis, founding executive director of the Soros Foundations; James A Harmon, senior advisor to the Rothschild Group, et al. US ruling circles have a messianic mission to create a world revolution, and it is no surprise that the ideological foundations of the US ‘world revolution’ were developed by Russophobic Trotskyites during the Cold War.[33] The task of publicly announcing the post-Soviet world revolution was allotted to President George W Bush. Speaking before the National Endowment for Democracy in 2003, Bush stated that the war on Iraq was a continuation of a ‘world democratic revolution’ that started in the Soviet bloc: ‘The revolution under former president Ronald Reagan freed the people of Soviet-dominated Europe, he declared, and is destined now to liberate the Middle East as well’.[34]

Gorbachev had prepared the deconstruction of the Soviet bloc in 1988, when he announced to the United Nations General Assembly a reversal of Soviet policy: Russia would not come to the defence of Warsaw Pact regimes in the event of revolt. Immediately after he met President Reagan and President-elect George Bush.[35]

The subverting of post-Soviet Russia has proceeded no less vigorously. Carl Gershman, president of the National Endowment for Democracy (NED), remarked that the Solidarity movement in Poland was created the year following Gorbachev’s UN speech, and set in motion the dismantling of the Soviet bloc, which he termed ‘a new concept of incremental democratic enlargement’, which NED calls ‘cross-border work’.[36] This had its origins ‘in a conference that was sponsored by the Polish-Czech-Slovak Solidarity Foundation in Wroclaw in early November of 1989’.[37] This movement continues to the present, Gershman stating:

‘And so cross-border work was born, and it has continued to expand ever since. The Polish-Czech-Slovak Solidarity Foundation went from providing support for desktop publishing in the Czech Republic and Slovakia to providing similar aid in Ukraine and Belarus, and today it works in Russia, Moldova, the Caucasus and Central Asia. Other Polish groups also engage in cross-border work, from the Foundation for Education for Democracy, an outgrowth of the Solidarity Teachers Union which provides training in civic education for teachers and NGO leaders throughout the former Soviet Union, to the East European Democratic Center which supports local media in Ukraine and Central Asia’.[38]

Just prior to Gorbachev’s warning to Putin about not standing for re-election, Gershman had commented that:

‘…Putin may be in control in Russia, but he has lost the support of the political elite which fears that his return to the presidency will usher in a period of Brezhnev-like stagnation and continued economic and societal decline… International groups should be prepared to provide whatever assistance is needed and desired by local actors. Areas of support would include party development and election administration and monitoring, strengthening civil society and independent media, and making available the expertise of specialists in such fields as constitutionalism and electoral law as well as the experience of participants in earlier transitions’.[39]

It was an unequivocal call to overthrow Putin.

RUSSIA AND THE NEW WORLD ORDER

Putin has embraced ‘Eruasianism’ as the alternative to a ‘new world order’ based around US hegemony. In a major foreign policy article in 2012 Putin outlined the main premises: Putin stated that Russian would be guided by her own interests first, based on Russia’s strength, and would not be dictated to by outsiders. While Putin uses the term ‘new world order’, it is one that is antithetical to the globalist version. He questions the US missiles being placed on Russia’s borders, and the continuing belligerence of NATO, stating that ‘The Americans have become obsessed with the idea of becoming absolutely invulnerable’.[40] Importantly, Putin is fully aware that globalist agendas are being imposed behind the faced of ‘human rights’, and criticises the selectivity by which this morality is applied:

‘The recent series of armed conflicts started under the pretext of humanitarian aims is undermining the time-honored principle of state sovereignty, creating a moral and legal void in the practice of international relations’.[41]

Putin refers to the ‘Arab Spring’, noting outside inference in a ‘domestic conflict’. ‘The revolting slaughter of Muammar Gaddafi… was primeval’, Putin states, and the Libyan scenario should not be permitted in Syria. He adds of the ‘regime changes,’

‘It appears that with the Arab Spring countries, as with Iraq, Russian companies are losing their decades-long positions in local commercial markets and are being deprived of large commercial contracts. The niches thus vacated are being filled by the economic operatives of the states that had a hand in the change of the ruling regime’. One could reasonably conclude that tragic events have been encouraged to a certain extent by someone’s interest in a re-division of the commercial market rather than a concern for human rights. [42]

Putin sees Russia developing her historic relations with the Arab states, despite the ‘regime changes’. He also points out the political uses that are being made of social media which played such a significant role in mobilising and agitating masses during the ‘Arab Spring’, and indeed in the ‘colour revolutions’ on Russia’s doorstep.[43] Putin also acknowledges the subversive role of the NGO’s not least of whose actions are being directed against Russia, stating: ‘…the activities of “pseudo-NGOs” and other agencies that try to destabilize other countries with outside support are unacceptable’. He remarks on the failure of US and NATO intervention in Afghanistan and mentions Russia’s historic relationship there.[44]

While Russia is seen as having an important role in the Asia-Pacific region, and Putin puts stress on alignment with a strong China he also declares:

‘Russia is an inalienable and organic part of Greater Europe and European civilization. Our citizens think of themselves as Europeans. We are by no means indifferent to developments in united Europe. That is why Russia proposes moving toward the creation of a common economic and human space from the Atlantic to the Pacific Ocean – a community referred by Russian experts to as “the Union of Europe,” which will strengthen Russia’s potential and position in its economic pivot toward the “new Asia.”’[45]

Putin refers to an exciting new vision of a bloc expanding form ‘Lisbon to Vladivostok’. He sees Russia’s acceptance to membership of the World Trade Organisation as ‘symbolic’, while having defended Russian’s interests. With Russia looking at the Asia-Pacific region, will she be a nexus between this region and Europe, or will she enter the region as a junior partner with China? Some geopolitical analysts are referring to a new geopolitical bloc, challenging both the USA and China, as Eurosiberia[46] rather than Eurasia.

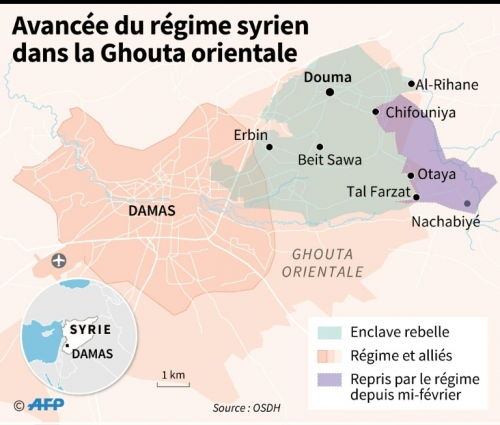

SYRIA: PIVOTAL ROADBLOCK IN THE GLOBALIST AGENDA

Now the world looks on again in confusion and fear as the USA extends its dialectical strategy of ‘controlled crises’ over one of the few remaining redoubts of independence: Syria. Again the lines of opposition are drawn between Russia and the USA in a geopolitical struggle for world conquest. Syria in fact has long been viewed as the major obstacle to globalist ambitions: moreso even than Libya, Iraq or Iran. In 1996 the Study Group for a New Israeli Strategy Toward 2000, established by the Institute for Advanced Strategic Studies, Jerusalem, issued a paper titled A Clean Break. The think tank included people who would become influential in the Bush Administration, such as Richard Perle, Douglas Feith and David Wurmser. The major obstacle was Syria, and the major aim was to ‘roll back Syria’, and to ‘foil Syria’s regional ambitions’. Even the recommendation of removing Saddam – ‘an important Israeli strategic objective in its own right’ – was seen as a step towards Syria.[47]

The 1996 paper recommends a propaganda offensive against Syria, along the lines of that employed against Saddam, and indeed against everyone who is an obstacle to the ‘new world order’ and/or Israel, suggesting that the ‘move to contain Syria’ be justified by ‘drawing attention to its weapons of mass destruction’.[48] The report suggests ‘securing tribal alliances with Arab tribes that cross into Syrian territory and are hostile to the Syrian ruling elite’. They suggest the weaning of Shia rebels against Syria.[49]

The plan of attack against Syria has been long in the making. Arab regimes have recently fallen like dominoes as a prelude to the elimination of Syria and Iran. The Clean Break recommends the use of Cold War type rhetoric in smearing Syria. We can see the plan unfolding before our eyes. The ‘weapons of mass destruction’ charade used to justify the US bombing of Syria takes the from of alleged chemical attacks on Syrian ‘civilians’, with a compliant media showing lurid pictures of suffering children, but usually with the comment that the reports are ‘unconfirmed’. The US assurances of ‘proof’ sound as unconvincing to the critical observer as the ‘evidence’ against Saddam. Sure enough, reports have come out that US-backed rebels have committed the chemical attacks as a means of securing a US assault on the Bashar al-Assad government. Two Western veteran journalists, while captives of the Free Syria Army, overheard their captors – including a FSA general – discussing the chemical weapons attack rebels had launched in Damascus as a means of provoking Western intervention.[50]

In an act of statesmanship, Putin pre-empted President Obama’s determination to bomb Syria by suggesting that Syria place its chemical weapons stockpiles for disposal with the United Nations; a plan that Syria has accepted.

Putin sees the offensive against Syria in world historical terms in determining what type of world is being moulded. While Russian ships face US and some French and British ships, he has rebuked Obama’s statements – like those of US presidents before him – that the USA has ‘an exceptional role’. In his appeal to the American people published in the New York Times, Putin questions the USA’s strategy stating that, ‘It is alarming that military intervention in internal conflicts in foreign countries has become commonplace for the United States’. Condemning the basis of the new world order’ that is being imposed with US weaponry, Putin writes that having studied Obama’s recent address:

…I would rather disagree with a case he made on American exceptionalism, stating that the United States’ policy is ‘what makes America different. It’s what makes us exceptional’. It is extremely dangerous to encourage people to see themselves as exceptional, whatever the motivation. There are big countries and small countries, rich and poor, those with long democratic traditions and those still finding their way to democracy. Their policies differ, too. We are all different, but when we ask for the Lord’s blessings, we must not forget that God created us equal.[51]

PUTIN STEERS A STRAIGHT COURSE

Putin has maintained his ideological position, and reiterated Russia’s determination to maintain her sovereignty and identity in the face of globalisation. Putin’s course for Russia was unequivocally stated in a September 2013 speech at a Government-backed plenary session of the Valdai Club, which included foreign dignitaries and Russian luminaries from politics, academia and media. Putin has declared himself a traditionalist and a nationalist who will not countenance interference in Russia’s interests.

To Putin, tradition and Christianity are the foundations of Russia’s independence, while the globalists seek to impose over the world a nihilistic creed where the fluctuating needs of the market place are the cultural basis of a ‘new world order’, Putin stating: ‘Without the values at the core of Christianity and other world religions, without moral norms that have been shaped over millennia, people will inevitably lose their human dignity’.[52] This indicates a Perennial Traditionalist approach whereby Putin refers to the core values shared by ‘Christianity and other world religions’, ‘against the modern world’[53] of the ‘Euro-Atlantic countries [where] any traditional identity, … including sexual identity, is rejected’.

Putin stated that while every nation needs its technical strength , at the basis of all is ‘spiritual, cultural and national self-determination’ without which ‘it is impossible to move forward’. ‘[T]he main thing that will determine success is the quality of citizens, the quality of society: their intellectual, spiritual and moral strength’. Putin rejects the economic determinism of the modern era, stating:

After all, in the end economic growth, prosperity and geopolitical influence are all derived from societal conditions. They depend on whether the citizens of a given country consider themselves a nation, to what extent they identify with their own history, values and traditions, and whether they are united by common goals and responsibilities. In this sense, the question of finding and strengthening national identity really is fundamental for Russia.

Putin pointed to the threat posed to Russian identity by ‘objective pressures stemming from globalisation’, as well as the blows to Russia inflicted by the attempts to erect a market economy, which it might be added, was sought by internal oligarchs and outside plutocrats; attempts that are ongoing. Putin moreover points to the lack of national identity serving these interests:

In addition, the lack of a national idea stemming from a national identity profited the quasi-colonial element of the elite – those determined to steal and remove capital, and who did not link their future to that of the country, the place where they earned their money.

What the globalists and oligarchs wish to impose on Russia from the outside cannot form an identity, which must arise from Russian roots, and not as a foreign import in the interests of commerce:

Practice has shown that a new national idea does not simply appear, nor does it develop according to market rules. A spontaneously constructed state and society does not work, and neither does mechanically copying other countries’ experiences. Such primitive borrowing and attempts to civilize Russia from abroad were not accepted by an absolute majority of our people. This is because the desire for independence and sovereignty in spiritual, ideological and foreign policy spheres is an integral part of our national character. Incidentally, such approaches have often failed in other nations too. The time when ready-made lifestyle models could be installed in foreign states like computer programmes has passed.

‘Russia’s sovereignty, independence and territorial integrity are unconditional’, states Putin. He has called for unity among all factions, above ethnic separatism and urges an ideological dialogue among political factions.

Putin also recognises that what is today called the ‘West’, with the USA as the ‘leader of the Western world’, as the media and US State Department constantly remind us, shows little evidence of any vestige of its traditional foundations:

Another serious challenge to Russia’s identity is linked to events taking place in the world. Here there are both foreign policy and moral aspects. We can see how many of the Euro-Atlantic countries are actually rejecting their roots, including the Christian values that constitute the basis of Western civilisation. They are denying moral principles and all traditional identities: national, cultural, religious and even sexual.

In this demise of Western values, Putin attacks ‘political correctness’, where religion has become an embarrassment, and Christian holidays are, for example, changed or eliminated in case a minority takes offence. This nihilism is being exported over the world and will result in a ‘profound demographic and moral crisis’, resulting the in ‘degradation’ of humanity. While multiculturalism is problematic for many states in Europe, Russia has always been multiethnic and this diversity should be encouraged in forging local identities, but within the context of a Russian state-civilisation. As will be apparent to the Russian leadership, the agitation of ethnic and religious separatism is a significant means by which the globalists undermine target nations, while paradoxically their own societies fall to pieces around them.[54]

Simultaneous with the moral and religious decline is the attempt to impose a ‘standardised, unipolar world’ where nations become defunct, rejecting the ‘God-given diversity’ of the world in favour of ‘vassals’. Above this, Putin is promoting a ‘Eurasian Union’, a geopolitical bloc that will enable the states of the region to withstand globalisation.

Putin’s Valdai speech shows that he has a fully developed world-view on which to base Russia’s future course. It also indicates that while Putin might have his faults (and I can’t think of what they might be offhand) he is the only actual statesmanin the world today, and has established Russia as the most likely axis of a new Civilisation and a new era. As history shows, once a civilisation succumbs to internal decay and often thereafter outside invasion, another civilisation assumes its place on the world state, created by a people who have retained their vigour and have not succumbed to moral rot. Western Civilisation reached its cycle of decay several centuries ago.

As Putin has pointed out, there is not much left that is traditionally Western. Today’s ‘Western’ zombie, animated by money, spreads its contagion over the world, as has no other civilization before it, as part of a deliberate world-mission, pointed out approvingly by such ‘neo-con’ strategists as Ralph Peters, who cites the USA’s cultural contamination of the world as a tactical manoeuvre.[55] Putin understands the forces that are swirling about the world like no other state leader; moreover not only understands the process, but overtly battles it like a modern-day ksatriya. Only in Russia are we witnessing the emergence of a new Civilisation fulfilling the Russian messianic mission that has long been written of by Russia’s sages. Only in Russia are we seeing the creation of a Traditionalist monolith standing against the forces of the Kali Yuga.

Kerry Bolton

Notes

[1] Viacheslav N Lutsenko, ‘Who are you Mr Putin?’, New Dawn, September-October 2001, p. 86.

[2] For example, as in the name of the neocon globalist think-tank, ‘Project for a New American Century’, http://www.newamericancentury.org/

[3] Susan Bryce, ‘Russia vs. the New World Order’, New Dawn, January-February 2001, p. 25.

[4] http://konservatizm.org/

[5] K R Bolton, ‘An ANZAC-Indo-Russian Alliance? Geopolitical Alternatives for New Zealand and Australian’, India Quarterly, Vol. 66, No. 2 (2010), pp. 183-201.

Also: K R Bolton, Geopolitics of the Indo-Pacific: Emerging Conflicts, New Alliances(London: Black House Publishing, 2013).

[6] Jean Thiriart interview with Gene H Hogberg, Part 5, http://home.alphalink.com.au/~radnat/thiriart/interview5....

[7] Anton Shekhovtsov, and Andreas Umland, ‘Is Aleksandr Dugin a Traditionalist? ‘Neo-Eurasianism’ and Perennial Philosophy’, The Russian Review, October, 2009, pp. 662–78.

[8] A Dugin, The Eurasian Idea, 2009.

[9] The Jamestown Foundation, ‘Mission’, http://www.jamestown.org/aboutus/

[10] K R Bolton, ‘Origins of the Cold War: How Stalin Foiled a New World Order’, 31 May 2010, http://www.foreignpolicyjournal.com/2010/05/31/origins-of...

K R Bolton, Stalin: the Enduring Legacy (London: Black House Publishing, 2012), pp. 125-139.

[11] See for example The Jamestown Foundation’s board members: ‘Board Members’, http://www.jamestown.org/aboutus/boardmembers/

[12] ‘The West’ is a misnomer, more accurately termed the ‘post-West’ under plutocratic control, as any notion of Western Culture has long since been smothered by Mammon.

[13] Jacob W Kipp, ‘The Elections are over and Putin won: whither Russia?’, 30 March 2012, http://www.jamestown.org/programs/edm/single/?tx_ttnews[t...

[14] K R Bolton, ‘Russia and China: an approaching conflict?’, Journal of Social, Political and Economic Studies, Vol. 34, no. 2, Summer 2009.

K R Bolton, ‘Aircraft Deployment in Russian Far East: Sign of Looming conflict?, Foreign Policy Journal, 27 May 2011, http://www.foreignpolicyjournal.com/2011/05/27/aircraft-d...

K R Bolton, ‘Sino-Soviet-US relations and the 1969 nuclear threat’, Foreign Policy Journal, 17 May 2010, http://www.foreignpolicyjournal.com/2010/05/17/sino-sovie...

K R Bolton, Geopolitics of the Indo-Pacific, op. cit.

[15] There need be no rivalry between Russia and India, but rather the continuation of the historical alignment between them.

[16] Jacob W Kipp. op. cit.

[17] Interestingly, Sergei Karganov, founder of the think tank, the Council for Foreign and Defense Policy, has been a member of the Rockefeller-founded globalist think tank, the Trilateral Commission since 1998, and a member of the International Advisory Board of the Council on Foreign Relations, 1995-2005; http://karaganov.ru/en/pages/biography

[18] K R Bolton, ‘An ANZAC-Indo-Russian Alliance’, op. cit.

[19] K R Bolton, ‘Aircraft Deployment is Russian Far East: Sign of Looming conflict?, op. cit.

[20] On Trilateralism see: The Trilateral Commission. ‘About the Organization: Purpose’, http://www.trilateral.org/about.htm

K R Bolton, ‘ANZAC-Indo-Russian Alliance…’, op. cit., ‘Asia-Pacific bloc pushed by USA, global business’.

[21] Jacob W Kipp, op. cit.

[22] Aleksandr Dugin, Argumenty i Fakty, March 14, 2012, cited by Kipp. Ibid.

[23] See: K R Bolton, ‘Russia and China: an approaching conflict?’, op. cit.

[24] Paul Joseph Watson, ‘Billionaire globalist warns Americans against resisting new global financial system, Soros: China Will Lead New World Order’, Prison Planet.com, October 28, 2009

[25] For a study on how Stalin set Russia on a course inimical to world plutocracy which has continued under Putin, with only the Gorbachev and Yeltsin interregna intervening, see: K R Bolton, Stalin : the Enduring Legacy, op. cit.

[26] K R Bolton, ‘Aircraft deployment in Russian Far East’…, op. cit.

[27] Paul Craig Roberts, ‘War on all fronts’, Foreign Policy Journal, 19 July 2012, http://www.foreignpolicyjournal.com/2012/07/19/war-on-all...

[28] Ibid.

[29] Reuters, ABC News, ‘Stars honour Gorbachev at gala birthday bash’, March 31, 2011, http://www.abc.net.au/news/stories/2011/03/31/3178823.htm).

[30] H Klaiman, “Peres attends Gorbachev’s birthday bash in London,” March 31, 2011, http://www.ynetnews.com/articles/0,7340,L-4050192,00.html

[31] Jack Kemp, et al, Russia’s Wrong Direction: What the United States Can and Should Do, Independent Task Force Report no. 57 (New York: Council on Foreign Relations, 2006) xi. The publication can be downloaded at: http://www.cfr.org/publication/9997/

[32] Ibid.

[33] K R Bolton, ‘America’s “World Revolution”: Neo-Trotskyist Foundations of US foreign policy’, Foreign Policy Journal, 3 May 2010, http://www.foreignpolicyjournal.com/2010/05/03/americas-w...

[34] Fred Barbash, ‘Bush: Iraq Part of “Global Democratic Revolution”: Liberation of Middle East Portrayed as Continuation of Reagan’s Policies’, Washington Post, 6 November 6, 2003.

[35] Dr. Svetlana Savranskaya and Thomas Blanton (ed.) ‘Previously Secret Documents from Soviet and U.S. Files n the 1988 Summit in New York, 20 Years Later’, National Security Archive Electronic Briefing Book No. 261, December 8, 2008.

[36] C Gershman, “Giving Solidarity to the world,” Georgetown University, May 19, 2009, http://www.ned.org/about/board/meet-our-president/archive...

[37] Ibid.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Carl Gershman, ‘The Fourth Wave: Where the Middle East revolts fit in the history of democratization – and how we can support them’, 14 March 2011, http://www.tnr.com/article/world/85143/middle-east-revolt...

[40] Vladimir Putin, ‘Russia and the changing world’, RiaNovosti, 27 February 2012, http://en.rian.ru/world/20120227/171547818.html

[41] Ibid.

[42] Ibid.

[43] See also: K R Bolton, ‘Twitters of the World Revolution: The Digital New-New Left’, Foreign Policy Journal, 28 February 2011, http://www.foreignpolicyjournal.com/2011/02/28/twitterers...

Also: K R Bolton, Revolution from Above, op. cit., pp. 235-240.

[44] V Putin, op. cit.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Guillaume Faye, ‘The New Concept of “Eurosiberia”’, Counter-Currents Publishing, http://www.counter-currents.com/2010/08/faye-on-eurosiber...

[47] A Clean Break, Study Group for a New Israeli Strategy Toward 2000, 1996, http://www.informationclearinghouse.info/article1438.htm

[48] Ibid., ‘Securing the Northern Border’.

[49] Ibid., ‘Moving to a Traditional Balance of Power Strategy’.

[50] ‘Journalist and writer held hostage for five months in Syria “overheard captors conversation blaming rebels for chemical attacks”’, Mail Online, 12 September 2013, http://www.dailymail.co.uk/news/article-2418378/Syrian-ho...

[51] Vladimir V Putin, ‘A Plea for Caution from Russia’, New York Times, 11 September 2013, http://www.nytimes.com/2013/09/12/opinion/putin-plea-for-...

[52] Putin at Valdai conference, Valdai Club, 19 September 2013, http://valdaiclub.com/valdai_club/62642.html

A significant proportion of the speech can be read at: http://therearenosunglasses.wordpress.com/2013/09/22/puti...

[53] To paraphrase the Traditionalist philosopher Julius Evola, Against the Modern World (Vermont: Inner Traditions International, 1995 [1969]).

[54] See K R Bolton, Babel Inc. (Black House Publications, 2013).

[55] Ralph Peters, ‘Constant Conflict ‘, Parameters, US Army War College Quarterly May 12, 1997, http://www.informationclearinghouse.info/article3011.htm

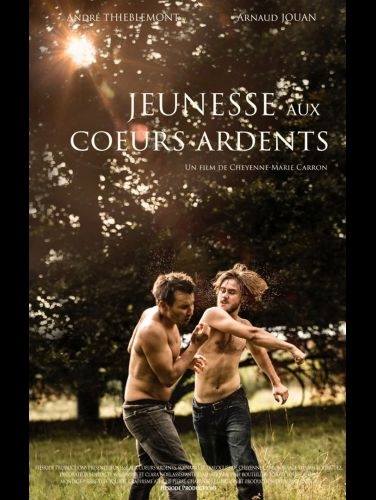

Un jour, leur victime est un ancien militaire ayant servi dans la Légion étrangère et ayant fait la guerre d’Algérie. Henri, « le capitaine », refuse de baisser les yeux comme le lui ordonne un complice de David. C’est là l’acte fondateur de ce qui, petit à petit, provoquera chez David une admiration, voire une fascination, pour cet homme âgé dont la vie consiste à défendre des valeurs fort éloignées de son monde à lui en même temps que l’honneur et la mémoire de ses anciens soldats.

Un jour, leur victime est un ancien militaire ayant servi dans la Légion étrangère et ayant fait la guerre d’Algérie. Henri, « le capitaine », refuse de baisser les yeux comme le lui ordonne un complice de David. C’est là l’acte fondateur de ce qui, petit à petit, provoquera chez David une admiration, voire une fascination, pour cet homme âgé dont la vie consiste à défendre des valeurs fort éloignées de son monde à lui en même temps que l’honneur et la mémoire de ses anciens soldats. Henri, lui, c’est André Thiéblemont, un véritable ancien officier de Légion. Dans le film, c’est un taiseux et ses silences sont souvent plus évocateurs que ses rares paroles. Ses yeux bleus parlent pour lui, mais c’est avant tout une « gueule » impressionnante et dont la vérité crue des expressions nous émeut.

Henri, lui, c’est André Thiéblemont, un véritable ancien officier de Légion. Dans le film, c’est un taiseux et ses silences sont souvent plus évocateurs que ses rares paroles. Ses yeux bleus parlent pour lui, mais c’est avant tout une « gueule » impressionnante et dont la vérité crue des expressions nous émeut.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Après la réélection de Vladimir Poutine ce 18 mars, le journaliste Frédéric Pons a expliqué à RT France que beaucoup de Russes ne comprenait pas «le ralliement, l'alignement de la France» sur le Royaume-Uni dans l'affaire de l'ex-espion empoisonné.

Après la réélection de Vladimir Poutine ce 18 mars, le journaliste Frédéric Pons a expliqué à RT France que beaucoup de Russes ne comprenait pas «le ralliement, l'alignement de la France» sur le Royaume-Uni dans l'affaire de l'ex-espion empoisonné.

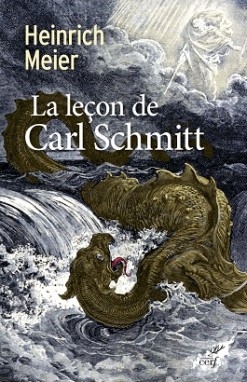

Chez ces deux auteurs, politique et religion sont mises ensemble, dans un même camp, dans une lutte opposant le bien au mal, même si ce qui représente le bien chez l’un représente le mal chez l’autre. Pour Schmitt, dans ce combat, le bourgeois est celui qui ne pense qu’à sa sécurité et qui veut retarder le plus possible son engagement dans ce combat entre bien et mal. Ce que le bourgeois considère comme le plus important, c’est sa sécurité, sécurité physique, sécurité de ses biens, comme de ses actions, «protection contre toute ce qui pourrait perturber l’accumulation et la jouissance de ses possessions» (p22). Il relègue ainsi dans la sphère privée la religion, et se centre ainsi sur lui-même. Or contre cette illusoire sécurité, Schmitt, et c’est là une thèse importante défendue par l’auteur, met au centre de l’existence la certitude de la foi («Seule une certitude qui réduit à néant toutes les sécurités humaines peut satisfaire le besoin de sécurité de Schmitt; seule la certitude d’un pouvoir qui surpasse radicalement tous les pouvoirs dont dispose l’homme peut garantir le centre de gravité morale sans lequel on ne peut mettre un terme à l’arbitraire: la certitude du Dieu qui exige l’obéissance, qui gouverne sans restriction et qui juge en accord avec son propre droit. (…) La source unique à laquelle s’alimentent l’indignation et la polémique de Schmitt est sa résolution à défendre le sérieux de la décision morale. Pour Schmitt, cette résolution est la conséquence et l’expression de sa théologie politique» (p24).). Et c’est dans cette foi que s’origine l’exigence d’obéissance et de décision morale. Schmitt croit aussi, comme il l’affirme dans sa Théologie politique, que «la négation du péché originel détruit tout ordre social».

Chez ces deux auteurs, politique et religion sont mises ensemble, dans un même camp, dans une lutte opposant le bien au mal, même si ce qui représente le bien chez l’un représente le mal chez l’autre. Pour Schmitt, dans ce combat, le bourgeois est celui qui ne pense qu’à sa sécurité et qui veut retarder le plus possible son engagement dans ce combat entre bien et mal. Ce que le bourgeois considère comme le plus important, c’est sa sécurité, sécurité physique, sécurité de ses biens, comme de ses actions, «protection contre toute ce qui pourrait perturber l’accumulation et la jouissance de ses possessions» (p22). Il relègue ainsi dans la sphère privée la religion, et se centre ainsi sur lui-même. Or contre cette illusoire sécurité, Schmitt, et c’est là une thèse importante défendue par l’auteur, met au centre de l’existence la certitude de la foi («Seule une certitude qui réduit à néant toutes les sécurités humaines peut satisfaire le besoin de sécurité de Schmitt; seule la certitude d’un pouvoir qui surpasse radicalement tous les pouvoirs dont dispose l’homme peut garantir le centre de gravité morale sans lequel on ne peut mettre un terme à l’arbitraire: la certitude du Dieu qui exige l’obéissance, qui gouverne sans restriction et qui juge en accord avec son propre droit. (…) La source unique à laquelle s’alimentent l’indignation et la polémique de Schmitt est sa résolution à défendre le sérieux de la décision morale. Pour Schmitt, cette résolution est la conséquence et l’expression de sa théologie politique» (p24).). Et c’est dans cette foi que s’origine l’exigence d’obéissance et de décision morale. Schmitt croit aussi, comme il l’affirme dans sa Théologie politique, que «la négation du péché originel détruit tout ordre social». La confrontation politique apparaît comme constitutive de notre identité. A ce titre, elle ne peut pas être seulement spirituelle ou symbolique. Cette confrontation politique trouve son origine dans la foi, qui nous appelle à la décision («La foi selon laquelle le maître de l’histoire nous a assigné notre place historique et notre tâche historique, et selon laquelle nous participons à une histoire providentielle que nos seules forces humaines ne peuvent pas sonder, une telle foi confère à chacun en particulier un poids qui ne lui est accordé dans aucun autre système: l’affirmation ou la réalisation du «propre» est en elle-même élevée au rang d’une mission métaphysique. Etant donné que le plus important est «toujours déjà accompli» et ancré dans le «propre», nous nous insérons dans la totalité compréhensive qui transcende le Je précisément dans la mesure où nous retournons au «propre» et y persévérons. Nous nous souvenons de l’appel qui nous est lancé lorsque nous nous souvenons de «notre propre question»; nous nous montrons prêts à faire notre part lorsque nous engageons ma confrontation avec «l’autre, l’étranger» sur «le même plan que nous» et ce «pour conquérir notre propre mesure, notre propre limite, notre propre forme.»« (p77-78).).

La confrontation politique apparaît comme constitutive de notre identité. A ce titre, elle ne peut pas être seulement spirituelle ou symbolique. Cette confrontation politique trouve son origine dans la foi, qui nous appelle à la décision («La foi selon laquelle le maître de l’histoire nous a assigné notre place historique et notre tâche historique, et selon laquelle nous participons à une histoire providentielle que nos seules forces humaines ne peuvent pas sonder, une telle foi confère à chacun en particulier un poids qui ne lui est accordé dans aucun autre système: l’affirmation ou la réalisation du «propre» est en elle-même élevée au rang d’une mission métaphysique. Etant donné que le plus important est «toujours déjà accompli» et ancré dans le «propre», nous nous insérons dans la totalité compréhensive qui transcende le Je précisément dans la mesure où nous retournons au «propre» et y persévérons. Nous nous souvenons de l’appel qui nous est lancé lorsque nous nous souvenons de «notre propre question»; nous nous montrons prêts à faire notre part lorsque nous engageons ma confrontation avec «l’autre, l’étranger» sur «le même plan que nous» et ce «pour conquérir notre propre mesure, notre propre limite, notre propre forme.»« (p77-78).). D’une part, Schmitt reproche à Hobbes d’artificialiser l’Etat, d’en faire un Léviathan, un dieu mortel à partir de postulats individualistes. En effet, ce qui donne la force au Léviathan de Hobbes, c’est une somme d’individualités, ce n’est pas quelque chose de transcendant, ou plus précisément, transcendant d’un point de vue juridique, mais pas métaphysique. A cette critique, il faut ajouter que, créé par l’homme, l’Etat n’a aucune caution divine: créateur et créature sont de même nature, ce sont des hommes. Or ces hommes, véritables individus prométhéens, font croire à l’illusion d’un nouveau dieu, né des hommes, et mortels, dont l’engendrement provient du contrat social. Et cette création à partir d’individus et non d’une communauté au sein d’un ordre voulu par Dieu, comme c’était, selon Hobbes, le cas au moyen-âge, perd par là-même sa légitimité aux yeux d’une théologie politique ( C. Schmitt écrit ainsi que: «ce contrat ne s’applique pas à une communauté déjà existante, créée par Dieu, à un ordre préexistant et naturel, comme le veut la conception médiévale, mais que l’Etat, comme ordre et communauté, est le résultat de l’intelligence humaine et de son pouvoir créateur, et qu’il ne peut naître que par le contrat en général.»).

D’une part, Schmitt reproche à Hobbes d’artificialiser l’Etat, d’en faire un Léviathan, un dieu mortel à partir de postulats individualistes. En effet, ce qui donne la force au Léviathan de Hobbes, c’est une somme d’individualités, ce n’est pas quelque chose de transcendant, ou plus précisément, transcendant d’un point de vue juridique, mais pas métaphysique. A cette critique, il faut ajouter que, créé par l’homme, l’Etat n’a aucune caution divine: créateur et créature sont de même nature, ce sont des hommes. Or ces hommes, véritables individus prométhéens, font croire à l’illusion d’un nouveau dieu, né des hommes, et mortels, dont l’engendrement provient du contrat social. Et cette création à partir d’individus et non d’une communauté au sein d’un ordre voulu par Dieu, comme c’était, selon Hobbes, le cas au moyen-âge, perd par là-même sa légitimité aux yeux d’une théologie politique ( C. Schmitt écrit ainsi que: «ce contrat ne s’applique pas à une communauté déjà existante, créée par Dieu, à un ordre préexistant et naturel, comme le veut la conception médiévale, mais que l’Etat, comme ordre et communauté, est le résultat de l’intelligence humaine et de son pouvoir créateur, et qu’il ne peut naître que par le contrat en général.»).

In the twentieth century, the Imperial Japanese developed soldier-Zen as a particular spiritual ethos compatible with their nation and state. This was advocated in particular by Lieutenant Colonel Sugimoto Gorō (1900-1937), who died in battle in China, and was honored by the Zen orders as a “military god” (gunshin).

In the twentieth century, the Imperial Japanese developed soldier-Zen as a particular spiritual ethos compatible with their nation and state. This was advocated in particular by Lieutenant Colonel Sugimoto Gorō (1900-1937), who died in battle in China, and was honored by the Zen orders as a “military god” (gunshin). There is an almost “national-pagan” quality to soldier-Zen’s sublimation of the self into an assertive nation mystically united around a divine monarch.

There is an almost “national-pagan” quality to soldier-Zen’s sublimation of the self into an assertive nation mystically united around a divine monarch. Socrates is supposed to have said that all philosophy is a preparation for death. By that definition, there is no doubt that Zen is a true philosophy. The Soto Zen leader Ishihara Shummyō said:

Socrates is supposed to have said that all philosophy is a preparation for death. By that definition, there is no doubt that Zen is a true philosophy. The Soto Zen leader Ishihara Shummyō said:

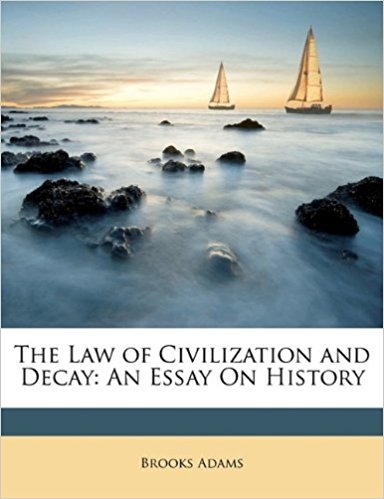

The Law of Civilization and Decay was published in 1896; that is, several decades prior to Spengler’s Decline of the West. Like Spengler, Adams traces through the analogous epochs of Civilizations the impact these epochs have upon the Culture in its entirety, from architecture to politics, focusing on the economic influences. He shows, like Spengler, that Civilizations proceed through organic cycles. Spengler used the names of seasons to illustrate the organic character of culture-life, going through the stages of birth (Spring; Culture), youthful vigor (Summer, High Culture), maturity (Autumn, Civilization), old age and senility (Winter), with an intervening era of revival – a dramatic final bow on the world stage – ending in death due to the primacy of money over spirit.

The Law of Civilization and Decay was published in 1896; that is, several decades prior to Spengler’s Decline of the West. Like Spengler, Adams traces through the analogous epochs of Civilizations the impact these epochs have upon the Culture in its entirety, from architecture to politics, focusing on the economic influences. He shows, like Spengler, that Civilizations proceed through organic cycles. Spengler used the names of seasons to illustrate the organic character of culture-life, going through the stages of birth (Spring; Culture), youthful vigor (Summer, High Culture), maturity (Autumn, Civilization), old age and senility (Winter), with an intervening era of revival – a dramatic final bow on the world stage – ending in death due to the primacy of money over spirit. Adams’ theory of energy seems akin to C. G. Jung on the ‘canalisation’ of psychical energy (libido);

Adams’ theory of energy seems akin to C. G. Jung on the ‘canalisation’ of psychical energy (libido); At this level, all Civilisations enter upon a stage, which lasts for centuries, of appalling depopulation. The whole pyramid of cultural man vanishes. It crumbles from the summit, first the world-cities, then the provincial forms, and finally the land itself, whose best blood has incontinently poured into the towns, merely to bolster them up awhile, at the last. Only the primitive blood remains, alive, but robbed of its strongest and most promising elements. This residue is the Fellah type.

At this level, all Civilisations enter upon a stage, which lasts for centuries, of appalling depopulation. The whole pyramid of cultural man vanishes. It crumbles from the summit, first the world-cities, then the provincial forms, and finally the land itself, whose best blood has incontinently poured into the towns, merely to bolster them up awhile, at the last. Only the primitive blood remains, alive, but robbed of its strongest and most promising elements. This residue is the Fellah type. Where there were slaves imported from the subject peoples, long since etiolated, filling an Italy whose population was being denuded, there is today an analogous process in an analogous epoch: that of immigration from the ‘third world’ into the Western states whose populations are ageing. Oligarchy constituted the core of the Empire. Nobility became defined by wealth.

Where there were slaves imported from the subject peoples, long since etiolated, filling an Italy whose population was being denuded, there is today an analogous process in an analogous epoch: that of immigration from the ‘third world’ into the Western states whose populations are ageing. Oligarchy constituted the core of the Empire. Nobility became defined by wealth.

As for Dugin’s influence in Russia, two antagonistic academics lament of him: ‘The growing interest among political scientists and other observers in Dugin and his activities is the result of his recent evolution from a little-known marginal radical right-winger to a notable and seemingly influential figure within Russia’s mainstream’.

As for Dugin’s influence in Russia, two antagonistic academics lament of him: ‘The growing interest among political scientists and other observers in Dugin and his activities is the result of his recent evolution from a little-known marginal radical right-winger to a notable and seemingly influential figure within Russia’s mainstream’. Citing a report from Chattham House by James Nixey, entitled ‘Russia’s Geopolitical Compass’, Nixey points to four ‘geostrategic axes for Russia: the West, Russia’s many ‘souths’ – the Black Sea region and the Islamic world – Russia’s Far East and the Arctic North’. Nixey states that Russia no longer views the ‘West’

Citing a report from Chattham House by James Nixey, entitled ‘Russia’s Geopolitical Compass’, Nixey points to four ‘geostrategic axes for Russia: the West, Russia’s many ‘souths’ – the Black Sea region and the Islamic world – Russia’s Far East and the Arctic North’. Nixey states that Russia no longer views the ‘West’ ‘According to Rousset, Putin would bring “bravery, foresight and pragmatism” to Russian policy in the interest of creating a geopolitical order from the Atlantic to Vladivostok. Rousset emphasized that Putin is a European from St. Petersburg working toward closer ties among Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. His conception of a Eurasian union had the possibility of creating an imperial order to rival that of the American empire and the emerging new orders in China and India

‘According to Rousset, Putin would bring “bravery, foresight and pragmatism” to Russian policy in the interest of creating a geopolitical order from the Atlantic to Vladivostok. Rousset emphasized that Putin is a European from St. Petersburg working toward closer ties among Russia, Ukraine and Belarus. His conception of a Eurasian union had the possibility of creating an imperial order to rival that of the American empire and the emerging new orders in China and India

The globalist think tanks are blatant in their intentions. The Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), opines that ‘Russia is heading in the wrong direction’.

The globalist think tanks are blatant in their intentions. The Council on Foreign Relations (CFR), opines that ‘Russia is heading in the wrong direction’.

Alexandre Douguine, Pour le Front de la Tradition, Ars Magna, collection « Heartland », 34 euros

Alexandre Douguine, Pour le Front de la Tradition, Ars Magna, collection « Heartland », 34 euros

On écoute ce maître qui, disait Borges, écrit la plus belle prose du monde :

On écoute ce maître qui, disait Borges, écrit la plus belle prose du monde :

Biographisches Rohmaterial

Biographisches Rohmaterial

Ernst Jüngers Rhodos-Reisen von 1938, 1964 und 1981

Ernst Jüngers Rhodos-Reisen von 1938, 1964 und 1981 Springtime for Ernst Jünger

Springtime for Ernst Jünger Stratege im Hintergrund

Stratege im Hintergrund Der Einzelne nach der Kehre

Der Einzelne nach der Kehre Unsere Total-Kalamität

Unsere Total-Kalamität

Et il est content (Philippe Muray était euphorique au moment de la tempête du siècle en l’an 2000) :

Et il est content (Philippe Muray était euphorique au moment de la tempête du siècle en l’an 2000) :

Quant à ce roman, gageons qu’il découragera plus d’un lecteur s’intéressant à cette période. Tant de personnages défilent qu’on ne parvient à s’attacher à aucun d’entre eux. On a en outre l’impression que l’auteur a voulu y fourguer toute sa documentation. Elle est d’autant plus vaste qu’il l’a largement puisée sur un site internet en libre accès: celui qu’Henri Thyssens consacre depuis 2005 à Robert Denoël. Mais on est loin de l’élégance d’un Pierre Assouline qui, à la fin de son roman Sigmaringen, tint à citer ses sources. Le travail de Thyssens est ici sommairement mentionné au détour d’une page alors que, sans les recherches qu’il a accumulées pendant vingt ans, ce roman n’existerait tout simplement pas. Quant au chercheur il est qualifié d’« admirateur de Louis-Ferdinand Céline », ce qui, dans l’esprit de l’auteur, doit être un tantinet suspect.

Quant à ce roman, gageons qu’il découragera plus d’un lecteur s’intéressant à cette période. Tant de personnages défilent qu’on ne parvient à s’attacher à aucun d’entre eux. On a en outre l’impression que l’auteur a voulu y fourguer toute sa documentation. Elle est d’autant plus vaste qu’il l’a largement puisée sur un site internet en libre accès: celui qu’Henri Thyssens consacre depuis 2005 à Robert Denoël. Mais on est loin de l’élégance d’un Pierre Assouline qui, à la fin de son roman Sigmaringen, tint à citer ses sources. Le travail de Thyssens est ici sommairement mentionné au détour d’une page alors que, sans les recherches qu’il a accumulées pendant vingt ans, ce roman n’existerait tout simplement pas. Quant au chercheur il est qualifié d’« admirateur de Louis-Ferdinand Céline », ce qui, dans l’esprit de l’auteur, doit être un tantinet suspect.

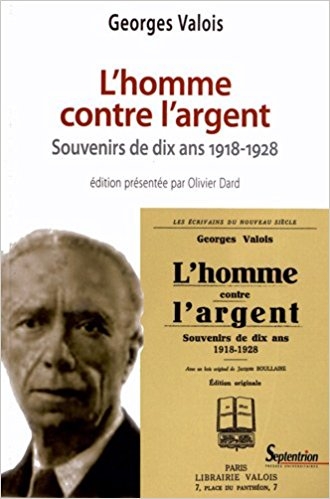

Lorsqu’il s’agit d’aborder le cas Georges Valois (1878-1945), c’est peut-être le terme de « rupture » qui s’impose en premier lieu à l’esprit. En effet, ce singulier personnage aura successivement adhéré aux idéologies marquantes de l’âge des extrêmes, de l’anarchisme à l’Action française (dont il sera un des premiers dissidents), d’un fascisme à la française clairement revendiqué au syndicalisme, jusqu’à enfin une doctrine économique trop peu étudiée encore, « l’abondancisme ».

Lorsqu’il s’agit d’aborder le cas Georges Valois (1878-1945), c’est peut-être le terme de « rupture » qui s’impose en premier lieu à l’esprit. En effet, ce singulier personnage aura successivement adhéré aux idéologies marquantes de l’âge des extrêmes, de l’anarchisme à l’Action française (dont il sera un des premiers dissidents), d’un fascisme à la française clairement revendiqué au syndicalisme, jusqu’à enfin une doctrine économique trop peu étudiée encore, « l’abondancisme ». Le livre, « virulent et écrit à chaud » selon les termes mêmes d’Olivier Dard, constitue un témoignage de première main sur une période de l’histoire souvent négligée au bénéfice des années 30, identifiées comme celles de tous les périls, de toutes les crises, de toutes les passions. Pourtant, quel bouillonnement déjà dans cette France qui sort à peine des tranchées, de la boue et du sang. L’heure est à la reconstruction et à la recherche de nouveaux modèles de société. Les uns ne jurent que par le monde anglo-saxon, les autres penchent plutôt du côté des Soviets. Valois revendique quant à lui l’ouverture d’une troisième voie dès l’incipit : « Ni Londres, ni Moscou. »

Le livre, « virulent et écrit à chaud » selon les termes mêmes d’Olivier Dard, constitue un témoignage de première main sur une période de l’histoire souvent négligée au bénéfice des années 30, identifiées comme celles de tous les périls, de toutes les crises, de toutes les passions. Pourtant, quel bouillonnement déjà dans cette France qui sort à peine des tranchées, de la boue et du sang. L’heure est à la reconstruction et à la recherche de nouveaux modèles de société. Les uns ne jurent que par le monde anglo-saxon, les autres penchent plutôt du côté des Soviets. Valois revendique quant à lui l’ouverture d’une troisième voie dès l’incipit : « Ni Londres, ni Moscou. »

— Lorsqu’on lit le chapitre consacré à la rupture avec l’AF, on entrevoit qu’il s’agit moins d’une dissension à propos des idées que d’histoires de gros sous et de concurrence d’organes de presse (L’Action française contre le Nouveau Siècle) qui motivent le départ de Valois. Aux yeux de l’historien, ce récit est-il sincère et complet ?

— Lorsqu’on lit le chapitre consacré à la rupture avec l’AF, on entrevoit qu’il s’agit moins d’une dissension à propos des idées que d’histoires de gros sous et de concurrence d’organes de presse (L’Action française contre le Nouveau Siècle) qui motivent le départ de Valois. Aux yeux de l’historien, ce récit est-il sincère et complet ?

•

•