ALAIN SANTACREU : Je suis né à Toulouse, au mitan du dernier siècle. Mes parents étaient des ouvriers catalans, arrivés en France en 1939, en tant que réfugiés politiques. J’ai vécu toute mon enfance et mon adolescence dans cette ville. J’y ai fait mes études, depuis l’école des Sept-Deniers jusqu’à l’ancienne Faculté des Lettres de la rue des Lois, en passant par le lycée Pierre de Fermat et le lycée Nord. C’est au Conservatoire de Toulouse, dans la classe de Simone Turck, que j’ai commencé ma formation théâtrale.

Je me suis marié très jeune et j’ai dû quitter Toulouse. Durant quelques années, j’ai joué dans diverses compagnies théâtrales de l’Est de la France. J’ai aussi été directeur d’un centre culturel, près de Belfort. Finalement, je suis devenu enseignant et j’ai exercé dans des établissements de la région parisienne. C’est au cours de cette période que j’ai écrit mes premiers textes et fondé la revue Contrelittérature. Par la suite mes activités éditoriales se sont diversifiées et, tout en publiant un premier roman et un recueil d’essais, j’ai dirigé plusieurs ouvrages collectifs sur l’art et la spiritualité, dans le cadre de la collection « Contrelittérature » aux éditions L’Harmattan. Quant à mon parcours intellectuel proprement dit, je l’aborderai en répondant à vos autres questions.

R/ Dans votre dernier roman Opera Palas vous placez le lecteur dans une posture opérative originale. Pensez-vous que le regard du lecteur « fait » vraiment un roman ?

R/ Dans votre dernier roman Opera Palas vous placez le lecteur dans une posture opérative originale. Pensez-vous que le regard du lecteur « fait » vraiment un roman ?

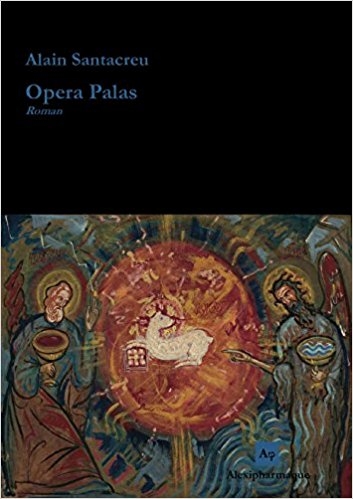

AS/ Toute la stratégie romanesque d’Opera Palas tourne autour de la phrase célèbre de Marcel Duchamp : « Ce sont les regardeurs qui font les tableaux ». C’est un commentaire qu’il a prononcé à propos de ses ready-made [1]. On sait que le ready made inventé par Duchamp est un vulgaire objet préfabriqué, prêt à l’emploi, comme son célèbre urinoir, « Fontaine », devenu un chef-d’oeuvre de l’art du XXe siècle.

Toute oeuvre d’art a deux pôles : le pôle de celui qui fait l’oeuvre et le pôle de celui qui la regarde. Dans le ready made, l’artiste s’efface du pôle créatif puisqu’il ne réalise pas l’objet « tout fait » qu’il donne à voir. Dès lors, la production de l’oeuvre ne dépend plus que du second pôle, du regardeur, celui de la réception. Ainsi, le ready made de Duchamp démontre que le goût esthétique n’est que la projection de l’ego du regardeur sur l’oeuvre.

Le spectacle – ce que j’appelle « littérature », comme j’aurai l’occasion de l’expliciter – est le pouvoir qui veut que je tienne mon rôle dans le jeu social dont il est l’unique metteur en scène. S’opposer à la volonté du spectacle, c’est donc mourir à soi-même, renoncer à ce faisceau de rôles qui me constitue, devenir réfractaire à cette image que la société me renvoie. Un texte signé Alaric Levant, paru récemment sur votre site internet, affirme que ce travail sur soi est un acte révolutionnaire : « Aujourd’hui, nous sommes face à une barricade bien plus difficile à franchir que celle des CRS : c’est l’Ego, c’est-à-dire la représentation que l’on a de soi-même »[2].

La démarche de Duchamp vise à nous extraire de la perspective spectaculaire, en cela elle annonce le situationnisme, la dernière avant-garde artistique et politique qui se soit manifestée dans notre société contemporaine. Le pouvoir du regardeur de décider si une pissotière est une oeuvre d’art est factice ; en réalité, c’est dans les coulisses que le meneur du spectacle décide de la seule norme esthétique qui puisse me faire exister au regard des autres.

Ainsi, les œuvres de l’art fonctionnent comme un immense kaléidoscope de miroirs que le regardeur manipule afin de customiser l’image qu’il a de lui-même. Plus encore : pour la pensée aliénée toute chose n’est que ready-made, marchandise « prête à l’emploi ». Votre goût esthétique est tout simplement le signe que vous êtes un moderne comme tout le monde. Si vous voulez être intégré dans le spectacle, vous devez vous conformer à l’exercice obligatoire de la différenciation mimétique – pour le dire à la manière de René Girard – de façon à vous assurer que vous appartenez bien à la classe de loisir – pour le dire à la manière de Thorstein Veblen.

Opera Palas est l’équivalent contre-littéraire du ready-made duchampien. Marcel Duchamp est un protagoniste du roman et son oeuvre maîtresse, La mariée mise à nu par ses célibataires, même – aussi appelée Le Grand verre – est l’élément déclencheur du récit. La vanité de vouloir jouer un rôle dans la société du spectacle, la quête du succès et son obtention, Duchamp les a analysées dans son oeuvre majeure.

En lisant, le lecteur est renvoyé à son propre acte interprétatif, le roman est le miroir de sa pensée. Cela est rendu possible parce que le moi du narrateur anonyme du roman s’efface au fur et à mesure qu’avance le récit. En effet, une véritable opération alchimique se joue entre le narrateur et son double : Palas.

Le personnage de Palas est le nom générique de tous les lecteurs zélés d’Opera Palas. Il y a deux types possibles de lecteur. Le premier est celui qui se conforte dans la certitude de son moi, le lecteur aliéné qui réagit à partir du prêt-à-penser que la « littérature » lui a inculqué – pour celui-là, ce roman n’est pas un roman et il renoncera très vite à le lire ou même, sous l’emprise de son propre conditionnement idéologique, il l’interprètera comme antisémite, fasciste, homophobe ou conspirationniste. Le second type de lecteur est celui dont le zèle lui permet d’entrer en relation avec l’œuvre, d’établir un dialogue avec elle et de faire de sa lecture une opération de désaliénation de sa pensée. Le lecteur zélé accepte la mise en danger d’une lecture cathartique qui l’amène à oser se regarder lire.

Lorsque le lecteur referme Opera Palas, il prend conscience qu’il n’a fait qu’un tour sur lui-même, étant donné que la dernière page du roman est la description de l’icône qui illustre la couverture du livre. C’est alors qu’il peut traverser le miroir.

R/ Comment définir votre démarche de "Contre-Littérature" ?

R/ Comment définir votre démarche de "Contre-Littérature" ?

AS/ Le texte germinatif de la contrelittérature est Le manifeste contrelittéraire. Ce texte est d’abord paru, en février 1999, dans le n°48 de la revue Alexandre dirigée par André Murcie ; puis, quelques mois plus tard, en postface de mon premier roman, Les sept fils du derviche, (Éditions Jean Curutchet, 1999). Par la suite, il sera repris et étayé dans l’ouvrage éponyme, paru en 2005 aux éditions du Rocher : La contrelittérature : un manifeste pour l’esprit. Dès le début, j’ai préféré lexicaliser le terme pour le différencier du mot composé « contre-littérature » déjà employé par la critique littéraire officielle.

La contrelittérature est donc née à la fin du XXe siècle, pendant cette période d’unipolarisation du monde dans laquelle Fukuyama disait voir la « fin de l’histoire ». L’idéologie postmoderne du consensus global a été façonnée, dès le XVIIIe, par une Weltanschauung qu’Alexis Tocqueville, dans L’Ancien Régime et la Révolution, nomme « l’esprit littéraire » de la modernité. En deux siècles, la littérature avait si intensément « homogénéisé » la pensée, qu’à l’orée du XXIe siècle, une pensée hétérogène, contradictoire, était presque devenue impensable ; d’où la nécessité d’inventer un néologisme pour désigner cet impensable, ce fut : « contrelittérature ».

Cela se fit à partir de la découverte de la logique du contradictoire de Stéphane Lupasco. Pour la contrelittérature, Stéphane Lupasco est un maillon d’une catena aurea qui se manifeste avec Héraclite et les présocratiques, en passant aussi, comme nous le verrons, par Pierre-Joseph Proudhon, un auteur très important dans ma démarche.

Il faut partir de la définition la plus large possible : la littérature, c’est non seulement le corpus de tous les récits à travers lesquels une civilisation se raconte, mais encore tous les textes poétiques où elle prend conscience de son propre être et cherche à le transformer. La littérature doit être perçue comme un organisme vivant, un système dynamique d’antagonismes, pour reprendre la terminologie lupascienne, dont la production dépend de deux sources d’inspiration contraires : une force « homogénéisante » en relation avec les notions d’uniformité, de conservation, de permanence, de répétition, de nivellement, de monotonie, d’égalité, de rationalité, etc. ; et, à l’opposé, une force « hétérogénéisante » en relation avec les notions de diversité, de différenciation, de changement, de dissemblance, d’inégalité, de variation, d’irrationnalité, etc. Ce principe d’antagonisme a été annihilé par la littérature moderne qui a imposé l’actualisation absolue de son principe d’homogénéisation et ainsi tenté d’effacer le pôle de son contraire, l’hétérogène « contrelittéraire ».

Tous les romans étaient devenus semblables, de plates « egobiographies » sans âme, il fallait verticaliser l’horizontalité carcérale à laquelle on voulait nous condamner, retrouver la sacralité de la vie contre sa profanation imposée. C’est pourquoi, dans une première phase, nous nous sommes attachés à valoriser l’impensé de la littérature, le récit mystique qui se fonde sur la désappropriation de l’ego. D’où la redécouverte du roman arthurien et de la quête du graal, la revisitation des grands mystiques de toutes sensibilités religieuses – par exemple le soufisme dans mon premier roman, Les sept fils du derviche. Cela a pu conforter l’image fausse d’une contrelittérature confite en spiritualité et se complaisant dans une forme d’ésotérisme. Très peu ont réellement perçu la dimension révolutionnaire de la contrelittérature.

Tous les romans étaient devenus semblables, de plates « egobiographies » sans âme, il fallait verticaliser l’horizontalité carcérale à laquelle on voulait nous condamner, retrouver la sacralité de la vie contre sa profanation imposée. C’est pourquoi, dans une première phase, nous nous sommes attachés à valoriser l’impensé de la littérature, le récit mystique qui se fonde sur la désappropriation de l’ego. D’où la redécouverte du roman arthurien et de la quête du graal, la revisitation des grands mystiques de toutes sensibilités religieuses – par exemple le soufisme dans mon premier roman, Les sept fils du derviche. Cela a pu conforter l’image fausse d’une contrelittérature confite en spiritualité et se complaisant dans une forme d’ésotérisme. Très peu ont réellement perçu la dimension révolutionnaire de la contrelittérature.

La contrelittérature est une tentative pour redynamiser le système antagoniste de la littérature. Il est évident que ce point d’équilibre des deux sources d’inspiration exerce une attraction sur tous les « grands écrivains ». Leurs oeuvres contiennent les deux antagonismes dans des proportions différentes mais tournent toutes autour de ce « foyer » de mise en tension. Il serait stupide de se demander si un écrivain est « contrelittéraire ». Toute création contient nécessairement à la fois des éléments littéraires et contrelittéraires. C’est le quantum antagoniste qui varie, c’est-à-dire le point de la plus haute tension entre les antagonismes constitutifs de l’oeuvre.

On ne peut percevoir la liberté qu’en surplomblant les contraires, en les envisageant ensemble, d’un seul regard, sans en exclure un au bénéfice de l’autre. Telle est la perpective romanesque d’Opera Palas. Mon roman se construit en effet sur une série d’antagonismes. J’en citerai quelques-uns : la cabale de la puissance et la cabale de l’amour, le bolchévisme stalinien et le slavophilisme de Khomiakov, le sionisme de Buber et le sionisme de Jabotinsky, l’individu (le moi) et la commune (le non-moi, le je collectif) ; le nationalisme politique et le nationalisme de l’intériorité, l’éros et l’agapé ; sans oublier, pour finir, le couplage scandaleux entre Buenaventura Durruti et José Antonio Primo de Rivera, les ennemis politiques absolus.

Ainsi, la contrelittérature reprend le projet fondamental du Manifeste du Surréalisme d’André Breton, à partir du point où les surréalistes l’ont abandonné en choisissant le stalinisme : « Tout porte à croire qu'il existe un certain point de l’esprit d'où la vie et la mort, le réel et l'imaginaire, le passé et le futur, le communicable et l'incommunicable, le haut et le bas cessent d’être perçus contradictoirement. Or c'est en vain qu'on chercherait à l'activité surréaliste un autre mobile que l'espoir de détermination de ce point. »

Le plus haut drame de l’homme, ce n’est pas tant To be or not to be mais bien plutôt To be and not to be. La vraie quête initiatique est celle de ce point d’équilibre entre l’être et le non-être, c’est cela le grand retour du tragique, un lieu où la tension entre les contraires est si intense que nous passons sur un autre plan : un saut de réalité où les contraires entrent en dialogue.

R/ Votre démarche se rapproche pour moi de l'ABC de la lecture d'Ezra Pound. Ce prodigieux poète est-il une influence pour vous ?

AS/ L’ABC de la lecture est un génial manuel de propédeutique à l’usage des étudiants en littérature. On y trouve des réflexions d’une clarté fulgurante, telle cette phrase qui vous plonge dans un puits de lumière : « Toute idée générale ressemble à un chèque bancaire. Sa valeur dépend de celui qui le reçoit. Si M. Rockefeller signe un chèque d’un million de dollars, il est bon. Si je fais un chèque d’un million, c’est une blague, une mystification, il n’a aucune valeur. » [3]

On voit que, pour Ezra Pound aussi, c’est le récepteur qui accorde son crédit à l’émetteur. Si un milliardaire émet un gros chèque, le récepteur l’estime tout de suite valable ; mais, par contre, si le même chèque est émis par un vulgaire péquenot, ce n’est pas crédible. On retrouve ici l’interrogation de la pissotière de Duchamp, qu’est-ce qui en fait une oeuvre d’art pour le regardeur ?

Bien sûr, ce n’est pas exactement ce que veut signifier Pound dans cette phrase de son ABC de la lecture mais je l’ai citée à cause de son allusion « économique », thème prégnant dans d’autres de ses ouvrages. Je pense à un livre comme Travail et usure ou encore au Canto XLV.

Ezra Pound est un des grands prédécesseurs de la contrelittérature. C’est à partir de lui que j’ai compris la similarité du processus d’homogénéisation de la littérature avec celui de l’usure. Pound a perçu de façon très subtile le phénomène de l’ « argent fictif ». Il insiste dans ses écrits sur la constitution et le développement de la Banque d’Angleterre, modèle du système bancaire moderne né en pays protestant où l’usure avait été autorisée par Élisabeth Tudor en 1571.

Ezra Pound est un des grands prédécesseurs de la contrelittérature. C’est à partir de lui que j’ai compris la similarité du processus d’homogénéisation de la littérature avec celui de l’usure. Pound a perçu de façon très subtile le phénomène de l’ « argent fictif ». Il insiste dans ses écrits sur la constitution et le développement de la Banque d’Angleterre, modèle du système bancaire moderne né en pays protestant où l’usure avait été autorisée par Élisabeth Tudor en 1571.

Pour comprendre la nature métaphysique du sacrilège qu’Ezra Pound dénonce sous le concept d’usure, il faudrait se reporter au onzième chant de L’Enfer de Dante – La Divine Comédie est une référence constante dans Les Cantos – qui condamne en même temps les usuriers et les sodomites pour avoir péché contre la bonté de la nature (« spregiando natura e sua bontade »). J’ai moi-même repris ce parallèle dans mon roman Opera Palas en relevant la synchronicité, durant la seconde partie du XVIIIe siècle, de l’émergence des clubs d’homosexuels – équivalents des molly houses – avec l’officialisation de l’usure bancaire – décret du 12 octobre 1789 autorisant le prêt à intérêt.

C’est en 1787, dans ses Éléments de littérature, que François de Marmontel utilisa pour la première fois le terme « littérature » au sens moderne. Il ne me semble pas que ce phénomène de la concomitance entre la littérature et l’usure ait jamais été pris en compte ni étudié avant la contrelittérature [4].

Le concept poundien d’Usura ne se laisse pas circonscrire aux seuls effets de l’économie capitaliste. Dans la société contemporaine globalisée, tous les signes sont devenus des métonymies du signe monétaire, à commencer par les mots de la langue, arbitraires et sans valeur.

L’usure littéraire consiste à vider les mots de leur sens pour leur prêter un sens abstrait. Usura entraîne le progrès de l’abstraction, c’est-à-dire de la séparation – en latin abstrahere signifie retirer, séparer. Usura ouvre le monde de la réalité virtuelle et referme celui de la présence réelle. Par l’usure, l’homme se retrouve séparé du monde.

Durant l’été 1912, Ezra Pound parcourut à pied les paysages du sud de la France, sur les pas des troubadours, afin de s’incorporer les lieux topographiques du jaillissement de la langue d’oc. La poésie poundienne est un combat contre l’usure. Chaque point de l’espace devient un omphalos, un lieu d’émanation du verbe, chaque pas une station hiératique. Ainsi est dépassée l’entropie littéraire du mot, l’érosion du sens par l’usure répétitive.

Ce que Pound, lecteur de Dante, nomme « Provence », correspond géographiquement à l’Occitanie et à la Catalogne. Ce pays évoquait pour lui une civilisation médiévale de l’amour qui s’oppose au capitalisme moderne. L’amour est le contraire de l’usure.

Cependant, Pound n’a pas su reconnaître la surrection du catharisme des troubadours dans l’anarchisme espagnol, ce que Gerald Brenan a très bien vu dans son Labyrinthe espagnol [5]. J’ai soutenu dans Opera Palas cette vision millénariste de la révolution sociale espagnole.

Cependant, Pound n’a pas su reconnaître la surrection du catharisme des troubadours dans l’anarchisme espagnol, ce que Gerald Brenan a très bien vu dans son Labyrinthe espagnol [5]. J’ai soutenu dans Opera Palas cette vision millénariste de la révolution sociale espagnole.

À mes yeux, la véritable trahison politique d’Ezra Pound ne se trouve pas tant dans les causeries qu’il donna sur Radio Rome, entre 1936 et 1944, la plupart consacrées à la littérature et à l’économie, mais dans son aveuglement face à ce moment métahistorique que fut la guerre d’Espagne. Comment n’a-t-il pas vu qu’Usura n’était plus dans les collectivités aragonaises et les usines autogérées de Catalogne ? Comment n’a-t-il pas entendu d’où soufflait le vent du romancero épique, la poésie de Federico García Lorca, d’Antonio Machado, de Rafael Alberti, de Miguel Hernández?

R/ La notion de tradition apparaît dans vos écrits depuis l’origine. Quelle définition en donneriez-vous ? Quel est votre rapport à l’oeuvre de Guénon ?

AS/ Selon moi, le paradigme essentiel de la tradition réside dans la notion d’anthropologie ternaire, tout le reste n’est que littérature ésotérique.

Jusqu’à la fin de la période romane, soit l’articulation des XIIe et XIIIe siècles, la « tripartition anthropologique » a été la référence de notre civilisation chrétienne occidentale [6]. La structure trinitaire de l’homme – Corps-Âme-Esprit – fut simultanément transmise à la « science romane » par les sources grecque et hébraïque. Sans doute, le ternaire grec, « soma-psyché-pneuma », ne correspond-il pas exactement au ternaire hébreu, « gouf-nephesh-rouach », mais les deux se fondent sur une tradition fondamentale qui inclut le spirituel dans l’homme.

Dieu est immanent à l’esprit, mais il est transcendant à l’homme psycho-corporel, telle est l’aporie devant laquelle nous place cette « tradition primordiale » dont parle René Guénon. L’esprit n’est pas humain mais divino-humain ; ou, plus précisément, il est le lieu de la rencontre entre la nature divine et la nature humaine. Il n’y a pas de vie spirituelle sans Dieu et l’homme. C’est comme faire l’amour : il faut être deux ! C’est pourquoi une « spiritualité » laïque ne sera jamais qu’un onanisme de l’esprit.

Cette tradition dialogique entre l’incréé et le créé m’évoque le mot principe « Je-Tu » de Martin Buber. L’existence humaine se joue, selon Buber, entre deux mots principes qui sont deux relations antagonistes : « Je-Tu » et « Je-Cela ». Le mot-principe Je-Tu ne peut être prononcé que par l’être entier mais, au contraire, le mot-principe Je-Cela ne peut jamais l’être : « Dire Tu, c’est n’avoir aucune chose pour objet. Car où il y a une chose, il y a autre chose ; chaque Cela confine à d’autres Cela. Cela n’existe que parce qu’il est limité par d’autres Cela. Mais là où l’on dit Tu, il n’y a aucune chose. Tu ne confine à rien. Celui qui dit Tu n’a aucune chose, il n’a rien. Mais il est dans la relation. » [7]

Cette tradition dialogique entre l’incréé et le créé m’évoque le mot principe « Je-Tu » de Martin Buber. L’existence humaine se joue, selon Buber, entre deux mots principes qui sont deux relations antagonistes : « Je-Tu » et « Je-Cela ». Le mot-principe Je-Tu ne peut être prononcé que par l’être entier mais, au contraire, le mot-principe Je-Cela ne peut jamais l’être : « Dire Tu, c’est n’avoir aucune chose pour objet. Car où il y a une chose, il y a autre chose ; chaque Cela confine à d’autres Cela. Cela n’existe que parce qu’il est limité par d’autres Cela. Mais là où l’on dit Tu, il n’y a aucune chose. Tu ne confine à rien. Celui qui dit Tu n’a aucune chose, il n’a rien. Mais il est dans la relation. » [7]

Cependant, si Buber oppose ainsi le monde du Cela au monde du Tu, il ne méprise pas pour autant un monde au détriment de l’autre. Il met en évidence leur nécessaire antagonisme. L’homme ne peut vivre sans le Cela mais, s’il ne vit qu’avec le Cela, il ne peut réaliser sa vocation d’homme, il demeure le « Vieil homme » et sa misérable vie, dénuée de la Présence réelle, l’ensevelit dans une réalité irreliée.

À l’intérieur de la relation du mot principe « Je-Tu », nous rentrons dans l’ordre du symbole. Le symbole est un langage qui nous permet de saisir l’immanence de la transcendance. Il n’est pas une représentation, il réalise une présence. La Présence divine ne peut être représentée, elle est toujours là.

L’effacement de la conception tripartite de l’homme correspond à la période liminaire de la mécanisation moderne de la technique. Le XIIIe siècle marque ce point d’inflexion du passage à la modernité. C’est durant la crise du XIIIe siècle, comme l’a appelée Claude Tresmontant [8], que la pensée du signe va remplacer la pensée du symbole. Le mot pour l’esprit bourgeois n’est pas l’expression du Verbe, il est un signe arbitraire qui lui permet de désigner l’avoir, la marchandise.

La logique du symbole est une logique du contradictoire. René Guénon, dans un de ses articles [9], affirme qu’un même symbole peut être pris en deux sens qui sont opposés l’un à l’autre. Les deux aspects antagoniques du symbole sont liés entre eux par un rapport d’opposition, si bien que l’un d’eux se présente comme l’inverse, le « négatif » de l’autre. Ainsi, nous retrouvons dans la structure du symbole ce point de passage, situé hors de l’espace-temps, en lequel s’opère la transformation des contraires en complémentaires.

La découverte de l’oeuvre de René Guénon a été décisive dans mon cheminement. Mes parents étaient des anarchistes espagnols et j’ai lu Proudhon, Bakounine et Kropotkine bien avant de lire Guénon. C’est la lecture de René Guénon qui m’a permis de me libérer de la pesanteur de l’idéologie anarchiste.

La découverte de l’oeuvre de René Guénon a été décisive dans mon cheminement. Mes parents étaient des anarchistes espagnols et j’ai lu Proudhon, Bakounine et Kropotkine bien avant de lire Guénon. C’est la lecture de René Guénon qui m’a permis de me libérer de la pesanteur de l’idéologie anarchiste.

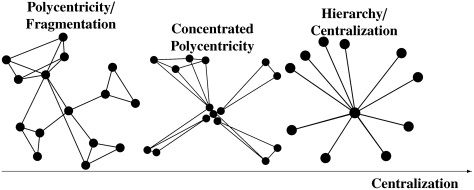

Toute erreur moderne n’est que la négation d’une vérité traditionnelle incomprise ou défigurée. Au cours de l’involution du cycle, le rejet d’une grille de lecture métaphysique du monde a provoqué la subversion de l’idée acrate, si chère à Jünger, et sa transformation en idéologie anarchiste. La négation des archétypes inversés de la bourgeoisie, à laquelle s’est justement livrée la révolte anarchiste ne pouvait qu’aboutir à un nihilisme indéfini, puisque son apriorisme idéologique lui interdisait la découverte des « archés » véritables. Cette incapacité fut l’aveu de son impuissance spirituelle à dépasser le système bourgeois. La négation du centre, perçu comme principe de l’autorité, au bénéfice d’une périphérie présupposée non-autoritaire, est l’expression d’une pensée dualiste dont la bourgeoisie elle-même est issue. La logique du symbole transmise par René Guénon ouvre une autre perspective où la tradition se conjugue à la révolution.

R/ Vous avez croisé la route de Jean Parvulesco. Pouvez-vous revenir sur cette personnalité flamboyante qui fut un ami fidéle de Rébellion ?

AS/ Jean Parvulesco et moi ne cheminions pas dans le même sens et nous nous sommes croisés, ce fut un miracle dans ma vie. Il est la plus belle rencontre que j’ai faite sur la talvera. Savez-vous ce qu’est la talvera ?

Les paysans du Midi appellent « talvera » cette partie du champ cultivé qui reste éternellement vierge car c’est l’espace où tourne la charrue, à l’extrémité de chaque raie labourée. Le grand écrivain occitan Jean Boudou a écrit un poème intitulé La talvera où l’on trouve ce vers admirable : « C’est sur la talvera qu’est la liberté » (Es sus la talvèra qu’es la libertat).

Mon intérêt pour la notion de talvera a été suscité par la lecture du sociologue libertaire Yvon Bourdet [10]. La talvera est l’espace du renversement perpétuel du sens, de sa reprise infinie, de son éternel retournement. Elle est la marge nécessaire à la recouvrance du sens perdu, à l’orientation donnée par le centre. Loin de nier le centre, la talvera le rend vivant. La conscience de la vie devenue de plus en plus périphérique, notre aliénation serait irréversible s’il n’y avait un lieu pour concevoir la rencontre, un corps matriciel où l’être, exilé aux confins de son état d’existence, puisse de nouveau se trouver relié à son principe. Sur la talvera se trouve l’éternel féminin de notre liberté, cette dimension mariale que Jean Parvulesco vénérait tant. C’est là que nous nous sommes rencontrés.

Mon intérêt pour la notion de talvera a été suscité par la lecture du sociologue libertaire Yvon Bourdet [10]. La talvera est l’espace du renversement perpétuel du sens, de sa reprise infinie, de son éternel retournement. Elle est la marge nécessaire à la recouvrance du sens perdu, à l’orientation donnée par le centre. Loin de nier le centre, la talvera le rend vivant. La conscience de la vie devenue de plus en plus périphérique, notre aliénation serait irréversible s’il n’y avait un lieu pour concevoir la rencontre, un corps matriciel où l’être, exilé aux confins de son état d’existence, puisse de nouveau se trouver relié à son principe. Sur la talvera se trouve l’éternel féminin de notre liberté, cette dimension mariale que Jean Parvulesco vénérait tant. C’est là que nous nous sommes rencontrés.

Jean Parvulesco était un « homme différencié », au sens où l’entendait Julius Evola. Il appartenait à cette race spirituelle engagée dans un combat apocalyptique contre la horde des « hommes plats ». Ce fut le dernier « maître de la romance ». Il est l’actualisation absolue de la contrelittérature. C’est-à-dire que Parvulesco inverse totalement le rapport littérature-contrelittérature. Son oeuvre à contre-courant potentialise l’horizontalité littéraire et actualise la verticalité contrelittéraire, pour employer la terminologie de Lupasco. D’un certain point de vue, Jean Parvulesco incarne le contraire de la littérature.

Je comprends aujourd’hui combien ma rencontre avec Parvulesco a été cruciale. Si notre éloignement m’est apparu comme une nécessité, j’ai su intérioriser sa présence, la rendre indispensable à ma propre démarche.

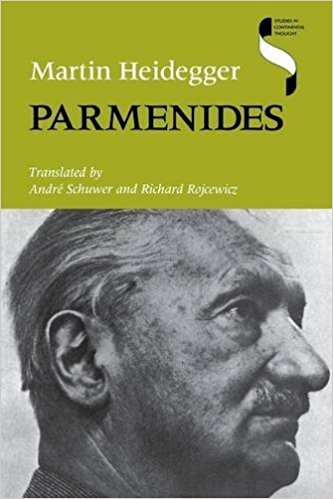

J’ai relu l’autre jour le texte qui a été la cause de notre séparation. C’était durant l’hiver 2002, son article s’intitulait « L’autre Heidegger » et aurait dû paraître dans le n° 8 de la revue Contrelittérature mais j’ai osé le lui refuser [11]. Parvulesco s’y interroge sur la véritable signification de l’œuvre d’Heidegger. Il soutient que la philosophie n’était qu’un moyen pour dissimuler un travail initiatique qu’Heidegger menait sur lui-même et qui se poursuivit jusqu’à son appel à la poésie d’Hölderlin, ultime phase de son oeuvre que Parvulesco nomme son « irrationalisme dogmatique ».

Or, ma démarche se résume à cette quête du point d’équilibre entre le rationalisme dogmatique des Lumières et l’irrationalisme dogmatique des anti-Lumières, ce point de la plus haute tension entre la littérature et la contrelittérature, alors que Jean Parvulesco incarnait le pôle contrelittéraire absolu.

On ne lit pas Jean Parvulesco sans crainte ni tremblement : la voie chrétienne qui s’y découvre est celle de la main gauche, un tantrisme marial aux limites de la transgression dogmatique. Son style crée dans notre langue française une langue étrangère au phrasé boréal. Mon ami, le romancier Jean-Marc Tisserant, qui l’admirait, me disait que Parvulesco était l’ombre portée de la contrelittérature en son midi : « Vous ne parlez pas de la même chose ni du même lieu », me confia-t-il lors de la dernière conversation que j'eus avec lui. Il est vrai que Parvulesco, à partir de notre séparation, a choisi d’orthographier « contre-littérature », en mot composé – sauf dans le petit ouvrage, Cinq chemins secrets dans la nuit, paru en 2007 aux éditions DVX, qu'il m'a dédié ainsi : « Pour Alain Santacreu et sa contrelittérature ».

On ne lit pas Jean Parvulesco sans crainte ni tremblement : la voie chrétienne qui s’y découvre est celle de la main gauche, un tantrisme marial aux limites de la transgression dogmatique. Son style crée dans notre langue française une langue étrangère au phrasé boréal. Mon ami, le romancier Jean-Marc Tisserant, qui l’admirait, me disait que Parvulesco était l’ombre portée de la contrelittérature en son midi : « Vous ne parlez pas de la même chose ni du même lieu », me confia-t-il lors de la dernière conversation que j'eus avec lui. Il est vrai que Parvulesco, à partir de notre séparation, a choisi d’orthographier « contre-littérature », en mot composé – sauf dans le petit ouvrage, Cinq chemins secrets dans la nuit, paru en 2007 aux éditions DVX, qu'il m'a dédié ainsi : « Pour Alain Santacreu et sa contrelittérature ».

J’ai repris dans le texte de mon roman, pour les trois seules occurrences où le mot apparaît, cette graphie « contre-littérature ». Ce mot désignait à ses yeux le combat pour l’être. Oui, finalement, la seule réalité qui vaille, c’est la réalité de ce combat. Il ne faut pas refuser de se battre, si l’on veut vaincre les forces antagonistes !

Ma rencontre avec Jean Parvulesco n’a pas été une « mérencontre », pour reprendre l’expression de Martin Buber, c’est-à-dire une rencontre qui aurait dû être et ne se serait pas faite. Notre rencontre a bien eu lieu, je l’ai compris en écrivant mon roman : Opera Palas, c’est l’accomplissement de ma rencontre avec Jean Parvulesco.

R/ Pour vous, comme pour Orwell, l’histoire s’arrête en 1936. Pourquoi ? Vous évoquez dans votre roman l’expérience de l’anarcho-syndicalisme de la CNT-AIT espagnole. Cette vision fédéraliste et libertaire est-elle la voie pour sortir de l’Âge de fer capitaliste ?

AS/ Comment faire pour s’extraire de l’« Âge de fer » capitaliste ? Alexandre Douguine [12] pense qu’il faut partir de la postmodernité – cette période qui, selon Francis Fukuyama, correspond à la « fin de l’histoire » – mais il commet une erreur de perspective : il faut partir du moment où l’histoire s’est arrêtée.

Selon Douguine, la chute de Berlin, en 1989, marque l’entrée de l’humanité dans l’ère postmoderne. La dernière décennie du XXe siècle aurait vu la victoire de la Première théorie politique de la modernité, le libéralisme, contre la Deuxième, celle du communisme – la Troisième théorie politique, le fascisme, ayant disparu avec la défaite du nazisme.

Je ne partage pas ce point de vue. Il n’y a pas eu de victoire de la Première théorie sur la Deuxième mais une fusion des deux dans un capitalisme d’État mondialisé. La postmodernité est anhistorique parce que l’histoire s’est arrêtée en 1936. C’est cela que j’ai voulu montrer avec Opera Palas. Le prétexte de mon roman est une phrase de George Orwell « Je me rappelle avoir dit un jour à Arthur Koestler : L’histoire s’est arrêtée en 1936. » Orwell écrit ces mots en 1942, dans un article intitulé « Looking Back on the Spanish War » (Réflexions sur la guerre d’Espagne). Et il poursuit : « En Espagne, pour la première fois, j’ai vu des articles de journaux qui n’avaient aucun rapport avec les faits, ni même l’allure d’un mensonge ordinaire. » Ainsi, parce que la guerre d’Espagne marque la substitution du mensonge médiatique à la vérité objective, l’histoire s’arrête et la période postmoderne s’ouvre alors.

Je ne partage pas ce point de vue. Il n’y a pas eu de victoire de la Première théorie sur la Deuxième mais une fusion des deux dans un capitalisme d’État mondialisé. La postmodernité est anhistorique parce que l’histoire s’est arrêtée en 1936. C’est cela que j’ai voulu montrer avec Opera Palas. Le prétexte de mon roman est une phrase de George Orwell « Je me rappelle avoir dit un jour à Arthur Koestler : L’histoire s’est arrêtée en 1936. » Orwell écrit ces mots en 1942, dans un article intitulé « Looking Back on the Spanish War » (Réflexions sur la guerre d’Espagne). Et il poursuit : « En Espagne, pour la première fois, j’ai vu des articles de journaux qui n’avaient aucun rapport avec les faits, ni même l’allure d’un mensonge ordinaire. » Ainsi, parce que la guerre d’Espagne marque la substitution du mensonge médiatique à la vérité objective, l’histoire s’arrête et la période postmoderne s’ouvre alors.

En 1936, contrairement à l’information unanimement répercutée par toute la presse internationale, les ouvriers et paysans espagnols ne se soulevèrent pas contre le fascisme au nom de la « démocratie » ni pour sauver la République bourgeoise ; leur résistance héroïque visait à instaurer une révolution sociale radicale. Les paysans saisirent la terre, les ouvriers s’emparèrent des usines et des moyens de transports. Obéissant à un mouvement spontané, très vite soutenu par les anarcho-syndicalistes de la CNT-FAI, les ouvriers des villes et des campagnes opérèrent une transformation radicale des conditions sociales et économiques. En quelques mois, une révolution communiste libertaire réalisa les théories du fédéralisme anarchiste préconisées par Proudhon et Bakounine. C’est cette réalité révolutionnaire que la presse antifasciste internationale reçut pour mission de camoufler. Du côté franquiste, la presse catholique et fasciste se livra aussi à une intense propagande de désinformation. À Paris, à Londres, comme à Washington ou à Moscou, la communication de guerre passa par le storytelling, la « mise en récit » d’une histoire qui présentait les événements à la manière que l’on voulait imposer à l’opinion. L’alliance des trois théories politiques a voulu détruire en Espagne la capacité communalisante du peuple. Ce que le bolchévisme avait fait subir au peuple russe, il est venu le réitérer en toute impunité en Espagne. C’est pourquoi je fais dans mon roman un parallèle entre les deux événements métahistoriques du XXe siècle où l’âme « communiste » des peuples a été annihilée : Cronstadt, en 1921 et Barcelone, lors des journées sanglantes de mai 1937.

Cronstadt voulait faire revivre le mir (commune rurale) et l’artel (coopérative ouvrière). Supprimer le mir archaïque signifiait supprimer des millions de paysans, c’est ce que firent les bolchéviques, par le crime et la famine.

Comme en Russie, les bolchéviques furent les fossoyeurs de la révolution sociale espagnole. Il suffit pour s’en convaincre de lire Spain Betrayed de Ronald Radosh, Mary R. Habeck et Grigory Sevostianov, un ouvrage qui procède au dépouillement systématique des dernières archives consacrées à la guerre d’Espagne, ouvertes à Moscou (Komintern, Politburo, NKVD – police politique et GRU – service d’espionnage de l’armée) [13]. Ainsi, bien au contraire de ce que dit Alexandre Douguine, si l’on prend la Guerre d’Espagne comme point focal, on comprend qu’il n’y a pas eu combat mais connivence entre les trois théories politiques de la modernité.

La vision fédéraliste et libertaire reste la seule méthode de guérison pour ranimer la capacité communalisante du peuple et lui permettre de retrouver son instinct de solidarité et de liberté.

L’anarcho-syndicalisme de la CNT espagnole n’a pas réussi à s’extraire de l’idéologie anarchiste pour s’ouvrir à l’esprit traditionnel de l’idée libertaire. C’est justement cette opération utopique – ou plutôt uchronique – que tente de mettre en place un des protagonistes du roman : Julius Wood.

Opera Palas établit un couplage insensé entre Buenaventura Durruti et José Antonio Primo de Rivera, une mise en relation scandaleuse et paradoxale qui prend à revers la notion même du politique telle que la résume Carl Schmitt dans cette phrase : « La distinction spécifique du politique, à laquelle peuvent se ramener les actes et les mobiles politiques, c’est la distinction de l’ami et de l’ennemi. » [14]

Le fédéralisme proudhonien repose sur cette mise en dialectique des contraires. Dans la pensée de Proudhon, le passage de l’anarchisme au fédéralisme est lié à cette recherche d’un équilibre entre l’autorité et la liberté dont un État garant du contrat mutualiste doit préserver l’harmonie.

On se rappellera la légende du « Grand Inquisiteur » que Dostoïevski a enchâssée dans Les Frères Karamazov : le Christ réapparaît dans une rue de Séville, à la fin du XVe siècle et, le reconnaissant, le Grand Inquisiteur le fait arrêter. La nuit, dans sa geôle, il vient reprocher au Christ la « folie » du christianisme : la liberté pour l’homme de se déifier en se tournant vers Dieu.

On se rappellera la légende du « Grand Inquisiteur » que Dostoïevski a enchâssée dans Les Frères Karamazov : le Christ réapparaît dans une rue de Séville, à la fin du XVe siècle et, le reconnaissant, le Grand Inquisiteur le fait arrêter. La nuit, dans sa geôle, il vient reprocher au Christ la « folie » du christianisme : la liberté pour l’homme de se déifier en se tournant vers Dieu.

Dans ce récit se trouve la quintessence du mystère du socialisme. Choisir les idées du Grand inquisiteur, comme le fera Carl Schmitt [15], qui en cela se révèle non seulement catholique mais « marxiste », c’est le socialisme d’État ; Bakounine, lui, à l’image de Tolstoï, choisit le Christ contre l’État, et c’est le socialisme anarchiste. Dépasser la contradiction entre Schmitt et Bakounine par la dialectique proudhonienne, telle est la théorie politique de l’avenir.

______________________

NOTES

[1] Marcel Duchamp, Ingénieur du temps perdu, Belfond, 1977, p. 122.

[2] Alaric Levant, « Une révolution de l’intérieur… pour faire avancer notre idéal ? » : http://rebellion-sre.fr/revolution-de-linterieur-faire-av....

[3] Ezra Pound, ABC de la lecture, coll. « Omnia », Éditions Bartillat, 2011, p. 27.

[4] Cf. « Talvera et Usura » paru dans Contrelittérature n° 17, Hiver 2006. Texte repris et développé dans le recueil d’essais Au coeur de la talvera, Arma Artis, 2010.

[5] Gerald Brenan, Le labyrinthe espagnol. Origines sociales et politiques de la guerre civile, Éditions Ruedo Ibérico, 1962.

[6] Jean Borella, « La tripartition anthropologique », in La Charité profanée, Éditions du Cèdre/DMM, 1979, pp.117-133.

[7] Martin Buber, « Je et Tu » in La Vie en dialogue, Aubier 1968, p. 8.

[8] Claude Tresmontant, La métaphysique du christianisme et la crise du treizième siècle, Éditions du Seuil, 1964.

[9] René Guénon, « Le renversement des symboles » in Le Règne de la Quantité et les Signes des Temps, chap. XXX.

[10] Yvon Bourdet, L’espace de l’autogestion, Galilée, 1979.

[11] Cet article a été intégré dans l’ouvrage de Jean Parvulesco, La confirmation boréale, Alexipharmaque éditions, 2012, pp. 223-229.

[12] Alexandre Douguine, La Quatrième théorie politique, Ars Magna Éditions, 2012.

[13] Édité en 2001, aux éditions Yale University, l’ouvrage est paru en Espagnol, en 2002, sous le titre España traicionada, mais n’a toujours pas été traduit en français.

[14] Carl Schmitt, La notion du politique, Calmann-Lévy, 1972, note 1, p.

66.

[15] Cf. Théodore Paléologue, Sous l’œil du grand inquisiteur : Carl Schmitt et l'héritage de la théologie politique, Cerf, 2004.

Gustave Le Bon affirme que l’évolution des institutions politiques, des religions ou des idéologies n’est qu’un leurre. Malgré des changements superficiels, une même âme collective continuerait à s’exprimer sous des formes différentes. Farouche opposant du socialisme de son époque, Gustave Le Bon ne croit pas pour autant au rôle de l’individu dans l’histoire. Il conçoit les peuples comme des corps supérieurs et autonomes dont les cellules constituantes sont les individus. La courte existence de chacun s’inscrit par conséquent dans une vie collective beaucoup plus longue. L’âme d’un peuple est le résultat d’une longue sédimentation héréditaire et d’une accumulation d’habitudes ayant abouti à l’existence d’un « réseau de traditions, d’idées, de sentiments, de croyances, de modes de penser communs » en dépit d’une apparente diversité qui subsiste bien sûr entre les individus d’un même peuple. Ces éléments constituent la synthèse du passé d’un peuple et l’héritage de tous ses ancêtres : « infiniment plus nombreux que les vivants, les morts sont aussi infiniment plus puissants qu’eux » (lois psychologiques de l’évolution des peuples). L’individu est donc infiniment redevable de ses ancêtres et de ceux de son peuple.

Gustave Le Bon affirme que l’évolution des institutions politiques, des religions ou des idéologies n’est qu’un leurre. Malgré des changements superficiels, une même âme collective continuerait à s’exprimer sous des formes différentes. Farouche opposant du socialisme de son époque, Gustave Le Bon ne croit pas pour autant au rôle de l’individu dans l’histoire. Il conçoit les peuples comme des corps supérieurs et autonomes dont les cellules constituantes sont les individus. La courte existence de chacun s’inscrit par conséquent dans une vie collective beaucoup plus longue. L’âme d’un peuple est le résultat d’une longue sédimentation héréditaire et d’une accumulation d’habitudes ayant abouti à l’existence d’un « réseau de traditions, d’idées, de sentiments, de croyances, de modes de penser communs » en dépit d’une apparente diversité qui subsiste bien sûr entre les individus d’un même peuple. Ces éléments constituent la synthèse du passé d’un peuple et l’héritage de tous ses ancêtres : « infiniment plus nombreux que les vivants, les morts sont aussi infiniment plus puissants qu’eux » (lois psychologiques de l’évolution des peuples). L’individu est donc infiniment redevable de ses ancêtres et de ceux de son peuple. La dilution des religions dans l’âme des peuples

La dilution des religions dans l’âme des peuples Ainsi, l’art de l’Egypte ancienne a irrigué la création artistique d’autres peuples pendant des siècles. Mais cet art, essentiellement religieux et funéraire et dont l’aspect massif et imperturbable rappelait la fascination des égyptiens pour la mort et la quête de vie éternelle, reflétait trop l’âme égyptienne pour être repris sans altérations par d’autres. D’abord communiqué aux peuples du Proche-Orient, cet art égyptien a inspiré les cités grecques. Mais Gustave Le Bon estime que ces influences égyptiennes ont irrigué ces peuples à travers le prisme de leur propre esprit. Tant qu’il ne s’est pas détaché des modèles orientaux, l’art grec s’est maintenu pendant plusieurs siècles à un stade de pâle imitation. Ce n’est qu’en se métamorphosant soudainement et en rompant avec l’art oriental que l’art grec connut son apogée à travers un art authentiquement grec, celui du Parthénon. A partir, d’un matériau identique qu’est le modèle égyptien transmis par les Perses, la civilisation indienne a abouti à un résultat radicalement différent de l’art grec. Parvenu à un stade de raffinement élevé dès les siècles précédant notre ère mais n’ayant que très peu évolué ensuite, l’art indien témoigne de la stabilité organique du peuple indien : « jusqu’à l’époque où elle fut soumis à la loi de l’islam, l’Inde a toujours absorbé les différents conquérants qui l’avaient envahie sans se laisser influencer par eux ».

Ainsi, l’art de l’Egypte ancienne a irrigué la création artistique d’autres peuples pendant des siècles. Mais cet art, essentiellement religieux et funéraire et dont l’aspect massif et imperturbable rappelait la fascination des égyptiens pour la mort et la quête de vie éternelle, reflétait trop l’âme égyptienne pour être repris sans altérations par d’autres. D’abord communiqué aux peuples du Proche-Orient, cet art égyptien a inspiré les cités grecques. Mais Gustave Le Bon estime que ces influences égyptiennes ont irrigué ces peuples à travers le prisme de leur propre esprit. Tant qu’il ne s’est pas détaché des modèles orientaux, l’art grec s’est maintenu pendant plusieurs siècles à un stade de pâle imitation. Ce n’est qu’en se métamorphosant soudainement et en rompant avec l’art oriental que l’art grec connut son apogée à travers un art authentiquement grec, celui du Parthénon. A partir, d’un matériau identique qu’est le modèle égyptien transmis par les Perses, la civilisation indienne a abouti à un résultat radicalement différent de l’art grec. Parvenu à un stade de raffinement élevé dès les siècles précédant notre ère mais n’ayant que très peu évolué ensuite, l’art indien témoigne de la stabilité organique du peuple indien : « jusqu’à l’époque où elle fut soumis à la loi de l’islam, l’Inde a toujours absorbé les différents conquérants qui l’avaient envahie sans se laisser influencer par eux ». La genèse des peuples

La genèse des peuples

Título:

Título: Los “Identitarios” son herederos de la reflexión sobre la identidad efectuada por los autores de la Nouvelle Droite hasta mediados de los años 80. No así de la reflexión sobre la identidad protagonizada posteriormente por Alain de Benoist, el cual rechaza estas derivas identitarias: este autor ha pasado de «una defensa de la identidad de los “nuestros” a un reconocimiento de la identidad de los “otros”». El propio Benoist toma distancias con la “afirmación étnica” de los Identitarios: «La reivindicación identitaria deviene en pretexto para legitimar la indiferencia, la marginación o la supresión de los “otros”. […] En tal perspectiva, la distinción entre “nosotros” y los “otros”, que es la base de toda identidad colectiva, se plantea en términos de desigualdad y de hostilidad por principio». En definitiva, se trata de una nueva generación identitaria que no ha combatido cultural ni políticamente en las filas de la Nouvelle Droite pero que, sin duda alguna, ha bebido en sus fuentes y ha leído sus publicaciones. Los propios Identitaires incluyen entre sus filiaciones ideológicas a la Nueva Derecha. Stéphane François, incluso, considera que la ideología identitaria es más antigua que la propia ND y que entroncaría con los grupúsculos organizados en torno a Europe-Action.

Los “Identitarios” son herederos de la reflexión sobre la identidad efectuada por los autores de la Nouvelle Droite hasta mediados de los años 80. No así de la reflexión sobre la identidad protagonizada posteriormente por Alain de Benoist, el cual rechaza estas derivas identitarias: este autor ha pasado de «una defensa de la identidad de los “nuestros” a un reconocimiento de la identidad de los “otros”». El propio Benoist toma distancias con la “afirmación étnica” de los Identitarios: «La reivindicación identitaria deviene en pretexto para legitimar la indiferencia, la marginación o la supresión de los “otros”. […] En tal perspectiva, la distinción entre “nosotros” y los “otros”, que es la base de toda identidad colectiva, se plantea en términos de desigualdad y de hostilidad por principio». En definitiva, se trata de una nueva generación identitaria que no ha combatido cultural ni políticamente en las filas de la Nouvelle Droite pero que, sin duda alguna, ha bebido en sus fuentes y ha leído sus publicaciones. Los propios Identitaires incluyen entre sus filiaciones ideológicas a la Nueva Derecha. Stéphane François, incluso, considera que la ideología identitaria es más antigua que la propia ND y que entroncaría con los grupúsculos organizados en torno a Europe-Action. Los militantes de Generación Identiraria se visten de colores amarillo y negro y han tomado como símbolo la letra griega “lambda” (^), que es también una referencia a los espartanos (spartiatas), especialmente a la película “300” realizada por Zack Snyder. El film 300, que es la adaptación del cómic de Frank Miller del mismo nombre, no es sólo una película popular que relata las guerras médicas entre griegos y persas. Este film está cargado de simbolismo para los militantes identitarios: los espartanos (representantes de la civilización europea) repelen la invasión de los persas (civilización no europea, originaria de Oriente Medio, hoy tierra musulmana). La analogía con los objetivos de los Identitarios es total: los europeos rechazan la invasión musulmana. Pero la representación simbólica va todavía más lejos: los espartanos son representados como filósofos y defensores de la democracia frente a los persas, representados como hordas de bárbaros. El hecho de que los espartanos combatieran la invasión de los persas les dotaría de una mayor legitimidad: como el recurso a la fuerza y a la violencia sólo estaría hoy moralmente legitimado para repeler una agresión, los Identitarios se situarían en la escena como víctimas de una invasión islámica –facilitada por la complaciente clase política– frente a la cual ellos deberían defender a su pueblo. Los militantes de GI forman parte plenamente de la llamada “generación 2.0”, lo cual es bastante apreciado por los dirigentes más adultos, porque la generación 2.0 controla las herramientas de internet, el marketing viral y el trabajo en redes.

Los militantes de Generación Identiraria se visten de colores amarillo y negro y han tomado como símbolo la letra griega “lambda” (^), que es también una referencia a los espartanos (spartiatas), especialmente a la película “300” realizada por Zack Snyder. El film 300, que es la adaptación del cómic de Frank Miller del mismo nombre, no es sólo una película popular que relata las guerras médicas entre griegos y persas. Este film está cargado de simbolismo para los militantes identitarios: los espartanos (representantes de la civilización europea) repelen la invasión de los persas (civilización no europea, originaria de Oriente Medio, hoy tierra musulmana). La analogía con los objetivos de los Identitarios es total: los europeos rechazan la invasión musulmana. Pero la representación simbólica va todavía más lejos: los espartanos son representados como filósofos y defensores de la democracia frente a los persas, representados como hordas de bárbaros. El hecho de que los espartanos combatieran la invasión de los persas les dotaría de una mayor legitimidad: como el recurso a la fuerza y a la violencia sólo estaría hoy moralmente legitimado para repeler una agresión, los Identitarios se situarían en la escena como víctimas de una invasión islámica –facilitada por la complaciente clase política– frente a la cual ellos deberían defender a su pueblo. Los militantes de GI forman parte plenamente de la llamada “generación 2.0”, lo cual es bastante apreciado por los dirigentes más adultos, porque la generación 2.0 controla las herramientas de internet, el marketing viral y el trabajo en redes. Los Identitarios reniegan de un Estado jacobino y unitario que viola las identidades locales tanto como los valores de la revolución francesa. En su comprensión de la identidad, los Identitarios se refieren a personajes prerrevolucionarios tales como los espartanos o incluso Charles Martel. Sus referencias hacen abstracción de los últimos siglos de historia de Francia para no recordar sino las referencias guerreras o romantizadas y edulcoradas de los campesinos trabajando la tierra (como puede comprobarse en los motivos medievales y caballerescos de sus carteles de propaganda).

Los Identitarios reniegan de un Estado jacobino y unitario que viola las identidades locales tanto como los valores de la revolución francesa. En su comprensión de la identidad, los Identitarios se refieren a personajes prerrevolucionarios tales como los espartanos o incluso Charles Martel. Sus referencias hacen abstracción de los últimos siglos de historia de Francia para no recordar sino las referencias guerreras o romantizadas y edulcoradas de los campesinos trabajando la tierra (como puede comprobarse en los motivos medievales y caballerescos de sus carteles de propaganda).

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

In his Parmenides, Martin Heidegger contributed an interesting remark in regards to the Greek term “polis”, which once again confirms the importance and necessity of serious etymological analysis. By virtue of its profundity, we shall reproduce this quote in full:

In his Parmenides, Martin Heidegger contributed an interesting remark in regards to the Greek term “polis”, which once again confirms the importance and necessity of serious etymological analysis. By virtue of its profundity, we shall reproduce this quote in full:

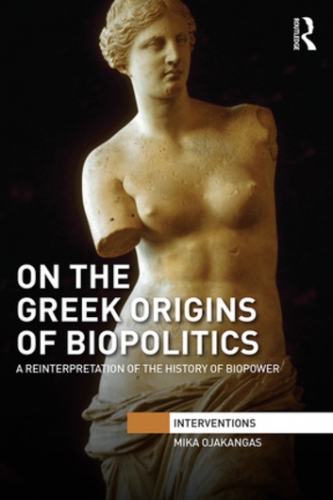

Ojakangas’ book has served to confirm my impression that, from an evolutionary point of view, the most relevant Western thinkers are found among the ancient Greeks, with a long sleep during the Roman Empire and the Middle Ages, a slow revival during the Renaissance and the Enlightenment, and a great climax heralded by Darwin, before being shut down again in 1945. The periods in which Western thought was eminently biopolitical — the fifth and fourth centuries B.C. and 1865 to 1945 — are perhaps surprisingly short in the grand scheme of things, having been swept away by pious Europeans’ recurring penchant for egalitarian and cosmopolitan ideologies. Okajangas also admirably puts ancient biopolitics in the wider context of Western thought, citing Spinoza, Nietzsche, Carl Schmitt, Heidegger, and others, as well as recent academic literature.

Ojakangas’ book has served to confirm my impression that, from an evolutionary point of view, the most relevant Western thinkers are found among the ancient Greeks, with a long sleep during the Roman Empire and the Middle Ages, a slow revival during the Renaissance and the Enlightenment, and a great climax heralded by Darwin, before being shut down again in 1945. The periods in which Western thought was eminently biopolitical — the fifth and fourth centuries B.C. and 1865 to 1945 — are perhaps surprisingly short in the grand scheme of things, having been swept away by pious Europeans’ recurring penchant for egalitarian and cosmopolitan ideologies. Okajangas also admirably puts ancient biopolitics in the wider context of Western thought, citing Spinoza, Nietzsche, Carl Schmitt, Heidegger, and others, as well as recent academic literature.

While Rome had also been founded as “a biopolitical regime” and had some policies to promote fertility and eugenics (120), this was far less central to Roman than to Greek thought, and gradually declined with the Empire. Political ideology seems to have followed political realities. The Stoics and Cicero posited a “natural law” not deriving from a particular organism, but as a kind of cosmic, disembodied moral imperative, and tended to emphasize the basic commonality of human beings (e.g. Cicero, Laws, 1.30).

While Rome had also been founded as “a biopolitical regime” and had some policies to promote fertility and eugenics (120), this was far less central to Roman than to Greek thought, and gradually declined with the Empire. Political ideology seems to have followed political realities. The Stoics and Cicero posited a “natural law” not deriving from a particular organism, but as a kind of cosmic, disembodied moral imperative, and tended to emphasize the basic commonality of human beings (e.g. Cicero, Laws, 1.30).

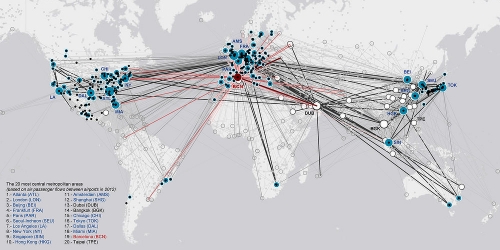

L'émergence d'une nouvelle économie techno-féodale qui distingue les information rich et les information-poor (et certes il ne suffit pas de se connecter sur le réseau pour être information rich) fait les délices des polémistes. Le gourou du management moderne Peter Drucker (photo) dénonce cette société qui fonctionne non plus à deux mais à dix vitesses : « Il y a aujourd'hui une attention démesurée portée aux revenus et à la richesse. Cela détruit l'esprit d'équipe. » Drucker comme le stupide Toffler, qui devraient se rappeler que Dante les mettrait au purgatoire en tant que faux devins, font mine de découvrir que la pure compétition intellectuelle génère encore plus d'inégalités que la compétition physique. C'est bien pour cela que les peuples dont les cultures symboliques sont les plus anciennes se retrouvent leaders de la Nouvelle Économie.

L'émergence d'une nouvelle économie techno-féodale qui distingue les information rich et les information-poor (et certes il ne suffit pas de se connecter sur le réseau pour être information rich) fait les délices des polémistes. Le gourou du management moderne Peter Drucker (photo) dénonce cette société qui fonctionne non plus à deux mais à dix vitesses : « Il y a aujourd'hui une attention démesurée portée aux revenus et à la richesse. Cela détruit l'esprit d'équipe. » Drucker comme le stupide Toffler, qui devraient se rappeler que Dante les mettrait au purgatoire en tant que faux devins, font mine de découvrir que la pure compétition intellectuelle génère encore plus d'inégalités que la compétition physique. C'est bien pour cela que les peuples dont les cultures symboliques sont les plus anciennes se retrouvent leaders de la Nouvelle Économie. William Gibson, l'inventeur du cyberspace, imaginait en 1983 une société duale gouvernée par l'aristocratie des cyber-cowboys naviguant dans les sphères virtuelles. La plèbe des non-connectés était désignée comme la viande. Elle relève de l'ancienne économie et de la vie ordinaire dénoncée par les ésotéristes. La nouvelle élite vit entre deux jets et deux espaces virtuels, elle décide de la consommation de tous, ayant une fois pour toutes assuré le consommateur qu'il n'a jamais été aussi libre ou si responsable. Dans une interview diffusée sur le Net, Gibson, qui est engagé à gauche et se bat pour un Internet libertaire, dénonce d'ailleurs la transformation de l'Amérique en dystopie (deux millions de prisonniers, quarante millions de travailleurs non assurés...).

William Gibson, l'inventeur du cyberspace, imaginait en 1983 une société duale gouvernée par l'aristocratie des cyber-cowboys naviguant dans les sphères virtuelles. La plèbe des non-connectés était désignée comme la viande. Elle relève de l'ancienne économie et de la vie ordinaire dénoncée par les ésotéristes. La nouvelle élite vit entre deux jets et deux espaces virtuels, elle décide de la consommation de tous, ayant une fois pour toutes assuré le consommateur qu'il n'a jamais été aussi libre ou si responsable. Dans une interview diffusée sur le Net, Gibson, qui est engagé à gauche et se bat pour un Internet libertaire, dénonce d'ailleurs la transformation de l'Amérique en dystopie (deux millions de prisonniers, quarante millions de travailleurs non assurés...). Les rois de l'algorithme vont détrôner les rois du pétrole. Les malchanceux ont un internaute fameux, Bill Lessard (photo), qui dénonce cette nouvelle pauvreté de la nouvelle économie. Lessard évoque cinq millions de techno-serfs dans la Nouvelle Économie, qui sont à Steve Case ce que le nettoyeur de pare-brise de Bogota est au patron de la General Motors. Dans la pyramide sociale de Lessard, qui rappelle celle du film Blade Runner (le roi de la biomécanique trône au sommet pendant que les miséreux s'entassent dans les rues), on retrouve les « éboueurs » qui entretiennent les machines, les travailleurs sociaux ou webmasters, les « codeurs » ou chauffeurs de taxi, les cow-boys ou truands de casino, les chercheurs d'or ou gigolos, les chefs de projet ou cuisiniers, les prêtres ou fous inspirés, les robots ou ingénieurs, enfin les requins des affaires. Seuls les quatre derniers groupes sont privilégiés. Le rêve futuriste de la science-fiction est plus archaïque que jamais. Et il est en train de se réaliser, à coups de bulle financière et de fusions ...

Les rois de l'algorithme vont détrôner les rois du pétrole. Les malchanceux ont un internaute fameux, Bill Lessard (photo), qui dénonce cette nouvelle pauvreté de la nouvelle économie. Lessard évoque cinq millions de techno-serfs dans la Nouvelle Économie, qui sont à Steve Case ce que le nettoyeur de pare-brise de Bogota est au patron de la General Motors. Dans la pyramide sociale de Lessard, qui rappelle celle du film Blade Runner (le roi de la biomécanique trône au sommet pendant que les miséreux s'entassent dans les rues), on retrouve les « éboueurs » qui entretiennent les machines, les travailleurs sociaux ou webmasters, les « codeurs » ou chauffeurs de taxi, les cow-boys ou truands de casino, les chercheurs d'or ou gigolos, les chefs de projet ou cuisiniers, les prêtres ou fous inspirés, les robots ou ingénieurs, enfin les requins des affaires. Seuls les quatre derniers groupes sont privilégiés. Le rêve futuriste de la science-fiction est plus archaïque que jamais. Et il est en train de se réaliser, à coups de bulle financière et de fusions ...

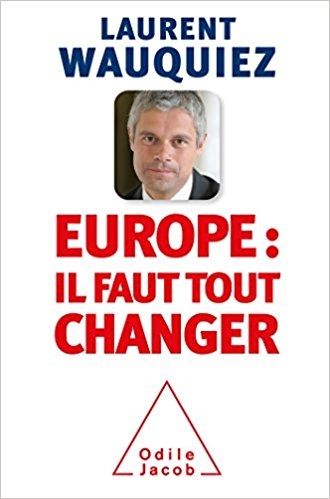

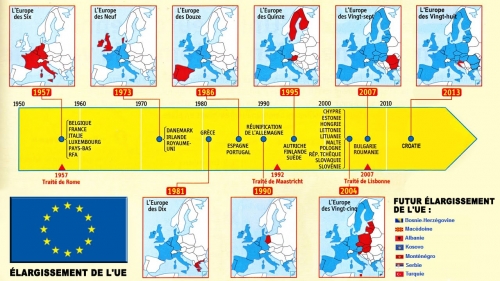

« La force de l’Europe est sans doute d’avoir été perpétuellement traversée par une envie d’ailleurs, une forme de doute existentiel qui nous a poussés à aller toujours plus loin, à nous questionner et à nous remettre sans cesse en cause. Ce besoin de dépassement est pour moi la plus belle forme de l’esprit européen (p. 290). » C’est à tort qu’on attribuerait ces deux phrases à Guillaume Faye. Leur véritable auteur n’est autre que Laurent Wauquiez, le nouveau président du parti libéral-conservateur de droite Les Républicains. Il avait publié au printemps 2014 Europe : il faut tout changer. Cet essai provoqua le mécontentement des centristes de son propre mouvement, en particulier celui de son mentor en politique, Jacques Barrot, longtemps député-maire démocrate-chrétien d’Yssingeaux en Haute-Loire. Après sa sortie sur le « cancer de l’assistanat » en 2011, ce livre constitue pour l’ancien maire du Puy-en-Velay (2008 – 2016) et l’actuel président du conseil régional Auvergne – Rhône-Alpes une indéniable tunique de Nessus. Il convient cependant de le lire avec attention puisqu’il passe de l’européisme béat à un euro-réalisme plus acceptable auprès des catégories populaires.

« La force de l’Europe est sans doute d’avoir été perpétuellement traversée par une envie d’ailleurs, une forme de doute existentiel qui nous a poussés à aller toujours plus loin, à nous questionner et à nous remettre sans cesse en cause. Ce besoin de dépassement est pour moi la plus belle forme de l’esprit européen (p. 290). » C’est à tort qu’on attribuerait ces deux phrases à Guillaume Faye. Leur véritable auteur n’est autre que Laurent Wauquiez, le nouveau président du parti libéral-conservateur de droite Les Républicains. Il avait publié au printemps 2014 Europe : il faut tout changer. Cet essai provoqua le mécontentement des centristes de son propre mouvement, en particulier celui de son mentor en politique, Jacques Barrot, longtemps député-maire démocrate-chrétien d’Yssingeaux en Haute-Loire. Après sa sortie sur le « cancer de l’assistanat » en 2011, ce livre constitue pour l’ancien maire du Puy-en-Velay (2008 – 2016) et l’actuel président du conseil régional Auvergne – Rhône-Alpes une indéniable tunique de Nessus. Il convient cependant de le lire avec attention puisqu’il passe de l’européisme béat à un euro-réalisme plus acceptable auprès des catégories populaires.

Il reste sur ce point d’une grande ambiguïté. « Toute tentation fédéraliste, tout renforcement quel qu’il soit des institutions européennes dans le cadre actuel doit être systématiquement rejeté (pp. 293 – 294). » Il est révélateur qu’il n’évoque qu’une seule fois à la page 187 la notion de subsidiarité. Il pense en outre qu’« il n’y a pas un peuple européen, et croire qu’une démocratie européenne peut naître dans le seul creuset du Parlement européen est une erreur. Il faut européaniser les débats nationaux (p. 139) ». Dommage que les Indo-Européens ne lui disent rien. Il reprend l’antienne de Michel Debré qui craignait que le Parlement européen s’érigeât en assemblée constituante continentale. « Construire l’Europe avec la volonté de tuer la nation est une profonde erreur (p. 285). » À quelle définition de la nation se rapporte-t-il ? La nation au sens de communauté de peuple ethnique ou bien l’État-nation, modèle politique de l’âge moderne ? En se référant ouvertement à la « Confédération européenne » lancée en 1989 – 1990 par François Mitterrand et à une « Europe en cercles concentriques » pensée après d’autres par Édouard Balladur tout en oubliant que celui-ci ne l’envisageait qu’en prélude à une intégration pro-occidentale atlantiste avec l’Amérique du Nord, Laurent Wauquiez soutient une politogenèse européenne à géométrie variable. Dans un scénario de politique-fiction qui envisage avec deux ans d’avance la victoire du Brexit, il relève que « le Royaume-Uni a quitté l’Union européenne suite à son référendum, mais a contribué à faire évoluer les 27 autres États membres pour qu’ils acceptent une forme plus souple de coopération autour d’un marché commun moins contraignant (p. 191) ». D’où une rupture radicale institutionnelle.

Il reste sur ce point d’une grande ambiguïté. « Toute tentation fédéraliste, tout renforcement quel qu’il soit des institutions européennes dans le cadre actuel doit être systématiquement rejeté (pp. 293 – 294). » Il est révélateur qu’il n’évoque qu’une seule fois à la page 187 la notion de subsidiarité. Il pense en outre qu’« il n’y a pas un peuple européen, et croire qu’une démocratie européenne peut naître dans le seul creuset du Parlement européen est une erreur. Il faut européaniser les débats nationaux (p. 139) ». Dommage que les Indo-Européens ne lui disent rien. Il reprend l’antienne de Michel Debré qui craignait que le Parlement européen s’érigeât en assemblée constituante continentale. « Construire l’Europe avec la volonté de tuer la nation est une profonde erreur (p. 285). » À quelle définition de la nation se rapporte-t-il ? La nation au sens de communauté de peuple ethnique ou bien l’État-nation, modèle politique de l’âge moderne ? En se référant ouvertement à la « Confédération européenne » lancée en 1989 – 1990 par François Mitterrand et à une « Europe en cercles concentriques » pensée après d’autres par Édouard Balladur tout en oubliant que celui-ci ne l’envisageait qu’en prélude à une intégration pro-occidentale atlantiste avec l’Amérique du Nord, Laurent Wauquiez soutient une politogenèse européenne à géométrie variable. Dans un scénario de politique-fiction qui envisage avec deux ans d’avance la victoire du Brexit, il relève que « le Royaume-Uni a quitté l’Union européenne suite à son référendum, mais a contribué à faire évoluer les 27 autres États membres pour qu’ils acceptent une forme plus souple de coopération autour d’un marché commun moins contraignant (p. 191) ». D’où une rupture radicale institutionnelle. La configuration actuelle à 28 ou 27 laisserait la place à une entente de six États (Allemagne, Belgique, Espagne, France, Italie et Pays-Bas) qui en exclurait volontairement le Luxembourg, ce paradis fiscal au cœur de l’Union. « Le noyau dur à 6 viserait une intégration économique et sociale forte (p. 185). » Il « pourrait s’accompagner d’un budget européen, poursuit encore Wauquiez, qui aurait comme vocation de financer de grands projets en matière de recherche, d’environnement et de développement industriel (p. 186). » On est très loin d’une approche décroissante, ce qui ne surprend pas venant d’un tenant du productivisme débridé. Cette « Union à 6 » serait supervisée par « une Commission restreinte à un petit nombre de personnalités très politiques qui fonctionnerait comme un gouvernement élu par le Parlement (pp. 187 – 188) ». S’il ne s’agit pas là d’une intégration fédéraliste, les mots n’ont aucun sens ! Laurent Wauquiez explique même que « la politique étrangère et la défense sont d’ailleurs toujours parmi les premières politiques mises en commun dans une fédération ou une confédération d’États (p. 92) ». Il n’a pas tort de penser que ce véritable cœur « néo-carolingien » (2) serait plus apte à peser sur les décisions du monde et surtout d’empêcher le déclin de la civilisation européenne. Faut-il pour le moins en diagnostiquer les maux ? « La première défaite, observe-t-il, c’est d’abord une Europe qui a renoncé à être une puissance mondiale. Elle accepte d’être un ventre mou sans énergie et sans muscle. Elle a abandonné toute stratégie et ne cherche plus à faire émerger des champions industriels (pp. 250 – 251) ». L’effacement de l’Europe a été possible par l’influence trouble des Britanniques. Londres imposa la candidature de l’insignifiante Catherine Ashton au poste de haut-représentant de l’Union pour les affaires étrangères et la politique de sécurité « a méthodiquement planifié par son inaction l’enlisement de la politique étrangère de sécurité et de défense (p. 90) ». Un jour, Laurent Wauquiez discute avec son homologue britannique. Quand il lui demande pourquoi avoir choisi cette calamité, le Britannique lui répond qu’« elle est déjà trop compétente pour ce qu’on attend d’elle et de la politique étrangère européenne, c’est-à-dire rien (p. 90) ». Résultat, le projet européen verse dans l’irénisme. « L’Europe a pensé que sa vertu seule lui permettrait de peser alors qu’il lui manquait la force, la menace, les outils d’une diplomatie moins morale mais plus efficace (p. 93). » L’essence de la morale diverge néanmoins de l’essence du politique (3).

La configuration actuelle à 28 ou 27 laisserait la place à une entente de six États (Allemagne, Belgique, Espagne, France, Italie et Pays-Bas) qui en exclurait volontairement le Luxembourg, ce paradis fiscal au cœur de l’Union. « Le noyau dur à 6 viserait une intégration économique et sociale forte (p. 185). » Il « pourrait s’accompagner d’un budget européen, poursuit encore Wauquiez, qui aurait comme vocation de financer de grands projets en matière de recherche, d’environnement et de développement industriel (p. 186). » On est très loin d’une approche décroissante, ce qui ne surprend pas venant d’un tenant du productivisme débridé. Cette « Union à 6 » serait supervisée par « une Commission restreinte à un petit nombre de personnalités très politiques qui fonctionnerait comme un gouvernement élu par le Parlement (pp. 187 – 188) ». S’il ne s’agit pas là d’une intégration fédéraliste, les mots n’ont aucun sens ! Laurent Wauquiez explique même que « la politique étrangère et la défense sont d’ailleurs toujours parmi les premières politiques mises en commun dans une fédération ou une confédération d’États (p. 92) ». Il n’a pas tort de penser que ce véritable cœur « néo-carolingien » (2) serait plus apte à peser sur les décisions du monde et surtout d’empêcher le déclin de la civilisation européenne. Faut-il pour le moins en diagnostiquer les maux ? « La première défaite, observe-t-il, c’est d’abord une Europe qui a renoncé à être une puissance mondiale. Elle accepte d’être un ventre mou sans énergie et sans muscle. Elle a abandonné toute stratégie et ne cherche plus à faire émerger des champions industriels (pp. 250 – 251) ». L’effacement de l’Europe a été possible par l’influence trouble des Britanniques. Londres imposa la candidature de l’insignifiante Catherine Ashton au poste de haut-représentant de l’Union pour les affaires étrangères et la politique de sécurité « a méthodiquement planifié par son inaction l’enlisement de la politique étrangère de sécurité et de défense (p. 90) ». Un jour, Laurent Wauquiez discute avec son homologue britannique. Quand il lui demande pourquoi avoir choisi cette calamité, le Britannique lui répond qu’« elle est déjà trop compétente pour ce qu’on attend d’elle et de la politique étrangère européenne, c’est-à-dire rien (p. 90) ». Résultat, le projet européen verse dans l’irénisme. « L’Europe a pensé que sa vertu seule lui permettrait de peser alors qu’il lui manquait la force, la menace, les outils d’une diplomatie moins morale mais plus efficace (p. 93). » L’essence de la morale diverge néanmoins de l’essence du politique (3). Autour de ce Noyau dur européen s’organiseraient en espaces concentriques une Zone euro à dix-huit membres, puis un marché commun de libre-échange avec la Grande-Bretagne, la Pologne et les Balkans, et, enfin, une coopération étroite avec la Turquie, le Proche-Orient et l’Afrique du Nord. Cette vision reste très mondialiste. L’auteur n’envisage aucune alternative crédible. L’une d’elles serait une Union continentale d’ensembles régionaux infra-européens. Au « Noyau néo-carolingien » ou « rhénan » s’associeraient le « Groupe de Visegrad » formellement constitué de la Pologne, de la Hongrie, de la Tchéquie, de la Slovaquie, de l’Autriche, de la Croatie et de la Slovénie, un « Bloc balkanique » (Grèce, Chypre, Bulgarie, Roumanie), un « Ensemble nordico-scandinave » (États baltes, Finlande, Suède, Danemark) et un « Axe » Lisbonne – Dublin, voire Édimbourg ? C’est à partir de ces regroupements régionaux que pourrait ensuite surgir des institutions communes restreintes à quelques domaines fondamentaux comme la politique étrangère, la macro-économie et la défense à condition, bien sûr, que ce dernier domaine ne soit plus à la remorque de l’Alliance Atlantique. Il est très révélateur que Laurent Wauquiez n’évoque jamais l’OTAN. Son Europe ne s’affranchit pas de l’emprise atlantiste quand on se souvient qu’il fut Young Leader de la French-American Foundation.

Autour de ce Noyau dur européen s’organiseraient en espaces concentriques une Zone euro à dix-huit membres, puis un marché commun de libre-échange avec la Grande-Bretagne, la Pologne et les Balkans, et, enfin, une coopération étroite avec la Turquie, le Proche-Orient et l’Afrique du Nord. Cette vision reste très mondialiste. L’auteur n’envisage aucune alternative crédible. L’une d’elles serait une Union continentale d’ensembles régionaux infra-européens. Au « Noyau néo-carolingien » ou « rhénan » s’associeraient le « Groupe de Visegrad » formellement constitué de la Pologne, de la Hongrie, de la Tchéquie, de la Slovaquie, de l’Autriche, de la Croatie et de la Slovénie, un « Bloc balkanique » (Grèce, Chypre, Bulgarie, Roumanie), un « Ensemble nordico-scandinave » (États baltes, Finlande, Suède, Danemark) et un « Axe » Lisbonne – Dublin, voire Édimbourg ? C’est à partir de ces regroupements régionaux que pourrait ensuite surgir des institutions communes restreintes à quelques domaines fondamentaux comme la politique étrangère, la macro-économie et la défense à condition, bien sûr, que ce dernier domaine ne soit plus à la remorque de l’Alliance Atlantique. Il est très révélateur que Laurent Wauquiez n’évoque jamais l’OTAN. Son Europe ne s’affranchit pas de l’emprise atlantiste quand on se souvient qu’il fut Young Leader de la French-American Foundation. Laurent Wauquiez méconnaît les thèses fédéralistes intégrales et non-conformistes. Il semble principalement tirailler entre Jean Monnet et Philippe Seguin. « Les deux sont morts aujourd’hui, et c’est la synthèse de Monnet et Séguin qu’il faut trouver si l’on veut sauver l’Europe (p. 18). » Cette improbable synthèse ne ferait qu’aggraver le mal. Wauquiez affirme que « Monnet et Séguin avaient raison et il faut en quelque sorte les réconcilier (p. 17) ». À la fin de l’ouvrage, il insiste une nouvelle fois sur ces deux sinistres personnages. « La vision de Monnet n’a sans doute jamais été aussi juste ni d’autant d’actualité (p. 293) » tandis que « définitivement, Philippe Séguin avait raison et le chemin suivi depuis maintenant vingt ans est en mauvais chemin (p. 291) ». Se placer sous le patronage à première vue contradictoire de Monnet et de Séguin est osé ! Jean Monnet le mondialiste agissait en faveur de ses amis financiers anglo-saxons. Quant à Philippe Séguin qui prend dorénavant la posture du Commandeur posthume pour une droite libérale-conservatrice bousculée par le « bougisme » macronien, cet ennemi acharné de la Droite de conviction représentait toute la suffisance, l’illusion et l’ineptie de l’État-nation dépassé. Sa prestation pitoyable lors du débat avec François Mitterrand au moment du référendum sur Maastricht en 1992 fut l’un des deux facteurs décisifs (le second était la révélation officielle du cancer de la prostate de Mitterrand) qui firent perdre le « Non » de justesse le camp du non. François Mitterrand n’aurait jamais débattu avec Marie-France Garaud, Philippe de Villiers ou Jean-Marie Le Pen…

Laurent Wauquiez méconnaît les thèses fédéralistes intégrales et non-conformistes. Il semble principalement tirailler entre Jean Monnet et Philippe Seguin. « Les deux sont morts aujourd’hui, et c’est la synthèse de Monnet et Séguin qu’il faut trouver si l’on veut sauver l’Europe (p. 18). » Cette improbable synthèse ne ferait qu’aggraver le mal. Wauquiez affirme que « Monnet et Séguin avaient raison et il faut en quelque sorte les réconcilier (p. 17) ». À la fin de l’ouvrage, il insiste une nouvelle fois sur ces deux sinistres personnages. « La vision de Monnet n’a sans doute jamais été aussi juste ni d’autant d’actualité (p. 293) » tandis que « définitivement, Philippe Séguin avait raison et le chemin suivi depuis maintenant vingt ans est en mauvais chemin (p. 291) ». Se placer sous le patronage à première vue contradictoire de Monnet et de Séguin est osé ! Jean Monnet le mondialiste agissait en faveur de ses amis financiers anglo-saxons. Quant à Philippe Séguin qui prend dorénavant la posture du Commandeur posthume pour une droite libérale-conservatrice bousculée par le « bougisme » macronien, cet ennemi acharné de la Droite de conviction représentait toute la suffisance, l’illusion et l’ineptie de l’État-nation dépassé. Sa prestation pitoyable lors du débat avec François Mitterrand au moment du référendum sur Maastricht en 1992 fut l’un des deux facteurs décisifs (le second était la révélation officielle du cancer de la prostate de Mitterrand) qui firent perdre le « Non » de justesse le camp du non. François Mitterrand n’aurait jamais débattu avec Marie-France Garaud, Philippe de Villiers ou Jean-Marie Le Pen…