Wieder einmal muss ich mich bei Tobias Wimbauer bedanken für den Hinweis auf diesen Artikel aus "Jungen Freiheit":

JF, 2/11 / 14. Oktober 2011

Michael Böhm

En poursuivant votre navigation sur ce site, vous acceptez l'utilisation de cookies. Ces derniers assurent le bon fonctionnement de nos services. En savoir plus.

Ex: http://www.ernst-juenger.org/

00:05 Publié dans Littérature, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : ernst jünger, révolution conservatrice, allemagne, littérature, littérature allemande, lettres, lettres allemandes |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

00:05 Publié dans Réflexions personnelles | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : soldats politiques, réflexions personnelles |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Jürgen Schwab

Ex: http://sachedesvolkes.wordpress.com/

Im Falle Syriens argumentieren westliche Medien ähnlich wie zuvor bei den Auseinandersetzungen in Libyen: Die Staatsführung schieße auf ihr eigenes Volk. Diese Behauptung entspricht nur einer Teilwahrheit, da die Rebellen nur einen Teil des Staatsvolkes repräsentieren, bei ihren Aktionen ebenso bewaffnet vorgehen wie die staatliche Armee. Westlichen Medien- und Geheimdienstkreisen geht es darum, Unruhen in Ländern, deren aktuelle Staatsführungen nicht nach der Pfeife von USA und Zionisten tanzen, einseitig als „Schlächter“ an ihrem eigenen Volk vorzuführen, um gegebenenfalls mittels militärischer Intervention einen „Regime Change“ (Staats- und Regierungswechsel) einzuleiten. Allerdings hält sich das westliche Lager im Falle Syriens noch zurück, da dieses Land in Sachen Rohstoffen weniger interessant ist (sinkende Ölförderung, wichtiger sind die Erdölleitungen, die das Land durchqueren). Geostrategische Bedeutung besitzt Syrien allerdings als Anrainer zu Israel, um dessen Sicherheitsinteresse die „Westliche Wertegemeinschaft“ besonders besorgt ist.

Nun wird man selbst in Washington und Jerusalem Zweifel daran haben, ob ein möglicher Systemwechsel in Damaskus in Richtung Islamismus auf Dauer dem Zionistenstaat mehr oder weniger Sicherheit bringt. Schließlich hat sich das Assad-System bislang mit der Abtrennung der Golanhöhen, die Israel 1967 im Sechstagekrieg eroberte, arrangiert – zwar nicht mit dem Gebietsraub abgefunden, aber es finden keine militärische Auseinandersetzungen um das Gebiet statt. Jörg Schönenborn, Moderator des „Presseclubs“ der ARD (vom 07.08.2011) meinte, daß die islamistischen Rebellen in Syrien „keine Demokratiebewegung“ im westlichen Sinne darstellten.

Laut der linken Berliner Tageszeitung „Junge Welt“ ist der militante Konflikt in Syrien durch Waffenschmuggel entstanden, der über die Grenze zum Libanon und über See abgewickelt werde. „Als die syrische Armee nun den Waffenschmuggel stoppen wollte, kam es zu Gefechten.“ („Junge Welt“ vom 21.06.2011) „Bereits seit langem subventionieren die USA syrische Oppositionsgruppen, nach eigenen Angaben mit etwa sechs Millionen Dollar jährlich, um die Unzufriedenheit zu schüren.“ (ebenda)

Die Unzufriedenheit an sich ist freilich nicht von den USA erfunden worden, die liegt vielmehr in bereits vorhandenen religiösen Gegensätzen begründet. So sind etwa 75 Prozent der Bevölkerung sunnitische Muslime. Die Einwohner von Hama, Palmyra und einigen kleineren Städten wie Dschisr asch-Schugur gelten als besonders konservativ. (vgl. den Eintrag im Internet-Lexikon „Wikipedia“ über Syrien) Die Stadt Hama im Süden des Landes, die derzeit von der syrischen Armee belagert wird (Stand 9. August 2011), ist die sunnitisch geprägte Hochburg des Widerstandes gegen den Staatspräsidenten Assad, der selbst den Alawiten (auch Nusairier genannt), einer schiitischen Abspaltungsgruppe, angehört. Schon 1982 kam es in Hama zu einem bewaffneten Aufstand von sunnitischen Islamisten gegen das laizistische System in Damaskus. Der damalige Staatspräsident war Hafiz al-Assad, Vater des heutigen Staatsoberhauptes Bachar al-Assad.

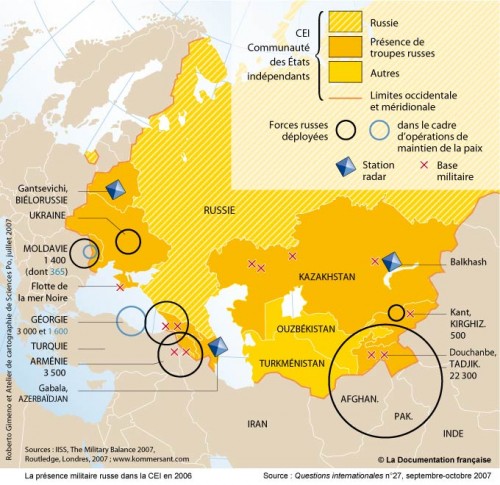

Das syrische System ähnelt in vielem dem nationalsozialistischen bzw. faschistischen Modell, in mancher Hinsicht auch – etwa in den vielen Staatsbetrieben und im Blockparteiensystem mit dem Führungsanspruch der Baath-Partei – der DDR (die Baath-Partei gab es auch bis 2003 im Regime von Saddam Hussein im Irak). In der Ära des Kalten Krieges galt Syrien – neben dem Irak, Libyen und Ägypten – als Bündnispartner der Sowjetunion, während die USA – bis heute als Schutzmacht Israels gelten. Anfang August dieses Jahres beschloß der UN-Sicherheitsrat eine recht ausgewogene Erklärung in Sachen Syrien, in der beide Seiten – Staatsführung und Rebellen – zur Mäßigung in dem Konflikt aufgerufen wurden. Diese Erklärung trägt die Handschrift der sogenannten BRICS-Staatengruppe (Brasilien, Rußland, Indien, China und Südafrika). Somit scheint Rußland wieder in seine alte Rolle als Schutzmacht Syriens zurückzufinden. Möglicherweise zieht man somit auch in Moskau die richtige Konsequenz aus der inkonsequenten Stimmenthaltung im Falle Libyens. Hier hätte Rußland mit einer Nein-Stimme sein Vetorecht einlegen und somit die UN-Aktion zu Fall bringen können. Die USA, Frankreich und Großbritannien hätten dann nur noch in einem Alleingang – ohne UN-Mandat – gegen das Gaddafi-Regime losschlagen können (wie 1999 gegen das Milosevic-Regime Jugoslawiens).

Wie im Irak spielen die USA auch in Syrien die Interessen zwischen ethnischen und Religionsgruppen gegeneinander aus. Laut Teilungsplänen der USA soll der südliche Teil des Landes an Jordanien abgetreten werden. Somit würde Syrien den sogenannten Hauran, die Kornkammer des Landes, verlieren. Der Teilungsplan des US-Geheimdienstes CIA reicht bis ins Jahr 1952. Ziel ist es, die Region „Großsyrien“ in viele kleine, ohnmächtige Nachbarn Israels zu zerstückeln. Dieser Konflikt begann bereits 1920. Die Osmanen mußten sich infolge des verlorenen Ersten Weltkrieges auf das Gebiet der heutigen Türkei zurückziehen. Unter der Leitung des Völkerbundes, dominiert von Frankreich und Großbritannien, begann die Aufteilung der ehemaligen osmanischen Provinz Großsyrien. Aus ihr wurden Palästina und der Libanon im Westen, Jordanien im Süden und im Osten der Irak – neben Syrien. („Junge Welt“, ebenda)

Jürgen Schwab

Bücher von Jürgen Schwab:

Die Manipulation des Völkerrechts. Wie die „Westliche Wertegemeinschaft” mit

Völkermordvorwürfen Imperialismus betreibt. Kyffhäuser Verlag, Mengerskirchen

2011, 14,95 Euro.

Angriff der neuen Linken – Herausforderung für die nationale Rechte. Hohenrain

Verlag, Tübingen 2009, 19,80 Euro.

Die „Westliche Wertegemeinschaft”, Abrechnung, Alternativen. Hohenrain Verlag,

Tübingen 2007, 19,50 Euro.

Volksstaat statt Weltherrschaft. Das Volk – Maß aller Dinge. Hohenrain Verlag,

Tübingen 2002, 9,80 Euro

00:13 Publié dans Actualité, Géopolitique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, politique internationale, syrie, proche orient, géopolitique, monde arabe, monde arabo-musulman |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Partie des Etats-Unis après la chute de Lehman Brothers, la crise économique a traversé l’Atlantique sans encombre pour venir heurter les frontières européennes. D’abord victime, l’Europe devient son propre bourreau en adoptant des politiques économiques peu efficaces. Pourtant, outre-Atlantique, la terre d’origine de la crise semble se débrouiller mieux que nous. Retour avec le blogueur Laurent Pinsolle, proche de Nicolas Dupont-Aignan, sur ces « divergences atlantiques ».

Partie des Etats-Unis après la chute de Lehman Brothers, la crise économique a traversé l’Atlantique sans encombre pour venir heurter les frontières européennes. D’abord victime, l’Europe devient son propre bourreau en adoptant des politiques économiques peu efficaces. Pourtant, outre-Atlantique, la terre d’origine de la crise semble se débrouiller mieux que nous. Retour avec le blogueur Laurent Pinsolle, proche de Nicolas Dupont-Aignan, sur ces « divergences atlantiques ».

Bien sûr, il ne s’agit pas ici de dire que les Etats-Unis sont un modèle en tout, loin de là. La baisse du taux de chômage est en partie due au fait qu’une part des demandeurs d’emplois renonce tout simplement à chercher un travail. En outre, le modèle étasunien a d’immenses limites et cette reprise ne résoudra rien aux problèmes de fond de ce pays. En somme, plane toujours le risque de coupes budgétaires massives si les démocrates et les républicains ne s’entendent pas.

En effet, étant encore loin de son pic de 2007, il a encore du potentiel de croissance. Mieux, le marché immobilier semble avoir touché son point bas, ce qui devrait créer des réserves de croissance pour les années à venir. Enfin, la Fed est fermement décidé à soutenir l’activité (ce qui fait partie de son mandat) et le gouvernement n’a pas hésité à recourir aux déficits pour relancer la croissance. Bref, il y a une forte conjonction de faits pour soutenir l’économie étasunienne.

De l’autre côté de l’Atlantique, comme le montre la dernière note de Patrick Artus pour Natixis, la zone euro s’enfonce dans la dépression. Il y a un an, la croissance devait s’accélérer en 2012. Au final, ce sera sans doute l’année de la rechute. Bien sûr, on prévoit un rebond en 2013, mais il est à peu près aussi crédible que le rebond qui était envisagé il y a un an pour 2012… Et la crise sans fin de la zone euro pénalise fortement la croissance en imposant des plans d’austérité.

En effet, comment imaginer la moindre reprise dans une zone où l’austérité s’impose partout avec des hausses d’impôt et des coupes de dépenses publiques qui cassent une croissance qui était déjà faible ? Et la BCE réserve ses aides au seul secteur bancaire. Et paradoxalement, le fait que les marchés européens automobiles et immobiliers aient beaucoup mieux résisté qu’aux Etats-Unis (à part en Espagne), laisse moins de réserve de croissance pour les années à venir.

Bref, comme le souligne depuis longtemps Joseph Stiglitz, les pays européens s’enferment dans des politiques qui ne mènent qu’à la dépression économique. Nous allons dans le mur, beaucoup l’annoncent depuis des années, mais les dirigeants européens continuent, pour sauver l’euro.

Laurent Pinsolle

00:12 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (1) | Tags : politique internationale, actualité, europe, affaires européennes, crise économique, crise financière, etats-unis |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Ex: http://www.unzensuriert.at/

Der Arabische Frühling hat bemerkenswerte Auswirkungen auf die Männer eines Dorfes im Nildelta. Fast alle sind mit bulgarischen Mädchen, die meisten von ihnen mit Roma-Herkunft, verheiratet. Mit Liebe haben diese Hochzeiten aber nichts zu tun. Laut der bulgarischen Tageszeitung „24 Tschassa“ stecken Menschenhändler hinter diesen Massenvermählungen, die angeblich nur eines im Sinn haben: den ägyptischen Männern über die EU-Staatsbürgerschaften der Frauen ein Visum zu besorgen.

Viele Indizien sprechen dafür. Im vergangenen Monat stellten 30 Ägypter Visa-Anträge in der bulgarischen Botschaft in Kairo. Als Begründung wurde eben Eheschließung angeführt. Die Behörden vermuten hinter der Aktion einen Verbrecher-Ring. Zwei Männer, ein Bulgare und ein Libanese, sollen den Frauen je 500 Euro bezahlt haben. Die beiden Männer hatten die Heiratswilligen im Alter von 20 bis 45 Jahren aus verschiedenen Teilen Bulgariens mit dem Bus nach Istanbul und mit dem Flugzeug nach Kairo gebracht.

Fraglich ist zudem, ob es tatsächlich Vermählungen gab. Diese sollen, wenn überhaupt, nach muslimischer Tradition vor einem Mullah und drei Zeugen vollzogen worden sein. Bulgarische Beamte gehen nach einem Bericht der Nachrichtenagentur Novinite davon aus, dass die Frauen ihre Ehe vor den Botschaftsbeamten lediglich bezeugen sollten, eine Vermählung nur fiktiv stattgefunden hätte. Es könnte sich also um einen glatten Betrug handeln, weshalb die Behörde jetzt alle Unterlagen genau prüfen will.

00:05 Publié dans Actualité, criminologie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : trafic de chair humaine, bulgarie, egypte, criminalité |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

00:05 Publié dans Manipulations médiatiques | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : orwell, novlangue, médias, manipulations médiatiques |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Ex: http://www.zuerst.de/

Helmut Schmidt auf dem Berliner Parteitag der SPD: Wie das Idol meiner Jugend sich um Kopf und Kragen redete

Ich ging eigentlich nur wegen Helmut Schmidt hin. Und wäre dann auch fast wieder umgekehrt: Die Hintergrundfarbe, in die die Sozis ihren Parteitag getaucht hatten, war zum Davonlaufen. Nannte man sie nicht mal „die Roten“? Übrig geblieben ist eine Mischung aus giftigem Magenta und Pink, mit der früher die Puffmütter ihre Fußnägel lackiert haben. Kann man sich vorstellen, daß unter diesen Farben demonstriert oder gar gestreikt wird?

Ich würgte meinen Ärger runter, es ging ja um Helmut Schmidt. Er war der Schwarm meiner jungen Jahre gewesen. Mei, wie hat der fesch ausgesehen, als Verteidigungsminister und als Kanzler: den Scheitel wie mit einem Skalpell gezogen, die preußische Haltung, die Gesichtsmuskeln straff vom vielen Rauchen. Einziger Nachteil: die Körpergröße. Aber Humphrey Bogart war auch nicht höher gewachsen, und trotzdem nahm man ihm immer ab, wenn er – zumindest in der deutschen Synchronisation – Ingrid Bergmann in Casablanca als „Kleines“ bezeichnete („Ich schau dir in die Augen, Kleines“). Alles eine Frage der Ausstrahlung. Die hatte Bogart, die hat Schmidt. Selbst wenn er, wie an diesem Tag, mit dem Rollstuhl hereingerollt wird.

Für mich war Schmidt immer die Verkörperung des patriotischen Sozialdemokraten gewesen. Diesen Typus, den man sich heute bei den ganzen Zottelbären wie Thierse und den parfümierten Silberfüchsen wie Steinmeier gar nicht mehr vorstellen kann, hat es einst tatsächlich gegeben: Rußgeschwärzt von Steinkohle und Reval standen die Bergleute an der Ruhr wie ein Mann hinter dieser Partei, oder – wie in Schmidts Heimat – die Schauer- und Seeleute aus den Hafenstädten. Proletarier aller Länder, das war nicht ihre Anrede – es waren vielmehr die Bataillone der „königlich preußischen Sozialdemokratie“, wie ihre kommunistischen Gegner einst spotteten. Sie lagen in den Schützengräben des Ersten oder – wie Schmidt – an den Fronten des Zweiten Weltkriegs. Sie ließen sich, wie Kurt Schumacher, in die Konzentrationslager sperren und kamen mit zerschlagenen Beinen wieder heraus – und kämpften auf Krücken weiter für Deutschland, gegen den „Alliiertenkanzler“ (Schumacher über Adenauer). Willy Brandt kritisierte John F. Kennedy wegen der Preisgabe Berlins beim Mauerbau, und seinen größten Wahlsieg fuhr er 1972 mit der Parole ein: „Deutsche, wir können stolz sein auf unser Land“. Die Kombination von „deutsch“ und „stolz“ – das würde man heute wahrscheinlich flugs der NPD zuordnen.

Nach Brandt kam Schmidt mit seinem Wahlslogan vom „Modell Deutschland“. Wenn er auf den Bundeskongressen der Jusos einritt, schaute er sie aus seinen Offiziersaugen an und schien ihnen sagen zu wollen: „Stillgestanden! Alle Spinner wegtreten, und zwar zackzack!“ In seinen Kanzlerjahren (1974 bis 1982) verteidigte er deutsche Interessen: Er wies Jimmy Carters Drängen nach einer weicheren, also unsolideren deutschen Geldpolitik schroff zurück. Den Saudis wollte er, gegen die Ausfälle des damaligen israelischen Premiers Menachim Begin, deutsche Leopard-Panzer liefern. Unvergessen sein Auftreten im Terrorjahr 1977: An der Spitze des Krisenstabes kommandierte er den Sturm der GSG-9 auf die entführte Lufthansa-Maschine in Mogadischu – vermutlich die erste deutsche Kommandoaktion nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg.

Voll mit diesen Erinnerungen fieberte ich an diesem schmuddeligen Dezembertag des Jahres 2011 Schmidts Rede entgegen – und wurde gnadenlos enttäuscht. Der Begriff, den er am häufigsten strapazierte, war die notwendige „Einbindung“ Deutschlands, das kam mindestens fünf oder sechsmal. Begründung: „Deutschland hat Stetigkeit und Zuverlässigkeit nötig.“ Denn: „Deutschland (löst) seit einem Jahrzehnt Unbehagen aus – neuerdings auch politische Besorgnis.“ Wodurch denn? Durch unsere Abstinenz bei den Überfällen auf den Irak und Libyen? Weil wir brav die Finanziers der EU und des Euro-Systems geben? Weil wir Musterschüler in Sachen Multikulti und Gender Mainstreaming sind?

Schmidt wäre nicht Schmidt, wenn er die notwendige „Einbindung“ Deutschlands nicht in einem langen historischen Rückblick mit Focus auf die NS-Zeit begründet hätte. „In absehbarer Zeit wird Deutschland kein ‚normales‘ Land sein.“ Das sei im „strategischen Interesse“ Deutschlands – „auch zum Schutze vor uns selbst“. Da ist er wieder, der „ewige Deutsche“ als der „ewige Nazi“, das Antifa-Pendant zum „ewigen Juden“ … Immerhin verschweigt Schmidt nicht, daß ihn dieses Denken einst in eine „ernstzunehmende Kontroverse“ mit Kurt Schumacher geführt hatte. Der war dann doch aus anderem Schrot und Korn.

Vor diesem Hintergrund redete Schmidt dem Parteitag ins Gewissen, bei den aktuellen Fragen der Euro-Rettung fünfe gerade sein zu lassen und das deutsche Füllhorn zur Finanzierung der defizitären Mitgliedstaaten zu öffnen. Eurobonds? Her damit! Aufkauf maroder Staatspapiere durch die EZB? Gerne! Schmidt urteilte apodiktisch: „Zwangsläufig wird auch eine gemeinsame Verschuldung unvermeidbar werden. Wir Deutschen dürfen uns dem nicht nationalegoistisch verweigern.“ Stattdessen sollen wir zahlen, zahlen, zahlen …

Dabei teile ich Schmidts Grundansatz, daß Deutschland die Integration in Europa braucht und als wirtschaftlich stärkste Macht auch etwas für die Schaffung eines prosperierenden und friedlichen Kontinents opfern muß. Die Vergangenheit hat gezeigt, daß sich unsere Nachbarn deutsche Kontrolle und Dominanz nicht bieten lassen, und der dann regelmäßig folgende Krieg war verlustreicher, viel verlustreicher als jede Euro-Rettung. Aber Schmidt übersieht, daß dieser kluge Ausgleich nur möglich ist nach dem Modell der europäischen Integration bis 1991 – als Bund souveräner Nationalstaaten mit gegenseitigen Handelsvorteilen und abgestimmter Geldpolitik, aber ohne Binnenmarkt und gemeinsame Währung, wie sie der Maastrichter Vertrag von 1991 auf den Weg gebracht hat. Die weit überdehnte Form der Integration, wie wir sie jetzt haben, wird geradewegs zu einem erneuten Gegensatz zwischen Deutschland und „den anderen“ und im Extremfall zum Krieg führen – also genau zu dem, was Schmidt mit Recht verhindern will. Denn was im Augenblick läuft, ist die Übernahme der Schulden, die Länder wie Griechenland und Italien gegenüber privaten Gläubigern haben, durch die Europäische Zentralbank und damit durch Deutschland als deren größtem Eigentümer. In der von CDU wie SPD gleichermaßen befürworteten Fiskalunion werden nicht die ursprünglichen Profiteure der Schuldenmacherei, die privaten Großbanken, für eine seriöse Tilgung sorgen müssen – sondern Deutschland als neuer Hauptgläubiger.

Schon wird in Athen, Lissabon und selbst in Paris die betuliche Hausfrau Angela Merkel nicht etwa mit der strengen Hausfrau Maggie Thatcher verglichen – sondern, darunter macht man es ja nicht, mit Adolf Hitler. Die „gemeinsame Verschuldung“, die Schmidt wie die gesamte politische Klasse befürwortet, führt zu einer geschlossenen Abwehrfront der meisten EU-Staaten gegen den deutschen Kern – also zu der Isolation unseres Landes, die er aus geschichtlicher Erfahrung verhindern will. Die mögliche Alternative sieht Schmidt nicht: Rückführung der europäischen Integration auf den Status vor den Maastrichter Verträgen 1991. Die Europäische Gemeinschaft (EG, früher EWG) hat nach dem Zweiten Weltkrieg für Frieden gesorgt – die Europäische Union (EU) hat ihn in der Folge gefährdet und droht ihn zu zerstören.

Katerina Stavropoulos

00:10 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : allemagne, politique internationale, europe, affaires européennes, helmut schmidt, euro, crise de l'euro, union européenne |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Ex: http://solidarisme.be

Van een verwaaide extremist die niet kan zwijgen over Hegel, Marx en Lacan is de Sloveense filosoof Slavoj Zizek uitgegroeid tot het boegbeeld van ieder die jong is en iets anders wil. De Occupiers dragen hem op handen, maar of hij blij is met al die eer, is een andere vraag.

MARNIX VERPLANCKE

'Toen ik in Wall Street het parkje naderde waar de Occupy-activisten zich verschanst hebben, kreeg ik dezelfde indruk als overal elders: hoe dichter je komt, hoe groter de teleurstelling wordt. Laten we eerlijk zijn, die mensen weten niet wat ze willen. Ze zouden een voorbeeld moeten nemen aan die Poolse overlevende van Auschwitz die ieder jaar naar het kamp trok en daar gewoon stond, in een stil protest. Maar nee, ze willen de wereld iets meedelen en dat is alleen maar bullshit zoals: 'Het geld moet de mensen dienen.' Daar zou zelfs Hitler het mee eens zijn geweest, want als het geld de mensen niet dient, dient het de Joodse bankiers. Ik hou anders wel van de term Occupy. Normaal verwijst die naar de machthebbers, die buitenlandse gebieden bezetten of kolonies stichten. Hier wordt dat omgedraaid. Dat is leuk, maar Occupy heeft geen programma en dat zal de dood zijn van die beweging."

'Toen ik in Wall Street het parkje naderde waar de Occupy-activisten zich verschanst hebben, kreeg ik dezelfde indruk als overal elders: hoe dichter je komt, hoe groter de teleurstelling wordt. Laten we eerlijk zijn, die mensen weten niet wat ze willen. Ze zouden een voorbeeld moeten nemen aan die Poolse overlevende van Auschwitz die ieder jaar naar het kamp trok en daar gewoon stond, in een stil protest. Maar nee, ze willen de wereld iets meedelen en dat is alleen maar bullshit zoals: 'Het geld moet de mensen dienen.' Daar zou zelfs Hitler het mee eens zijn geweest, want als het geld de mensen niet dient, dient het de Joodse bankiers. Ik hou anders wel van de term Occupy. Normaal verwijst die naar de machthebbers, die buitenlandse gebieden bezetten of kolonies stichten. Hier wordt dat omgedraaid. Dat is leuk, maar Occupy heeft geen programma en dat zal de dood zijn van die beweging."

De Sloveense filosoof Slavoj Zizek staat erom bekend zijn mening niet onder stoelen of banken te steken en daarbij steevast tegen de haren van zijn geestesverwanten in te strijken. Hij is de communist die in de jaren tachtig door het Joegoslavische communistische regime een beroepsverbod van vijf jaar opgelegd kreeg, de psychoanalyticus die met zijn constante geëmmer over Hegel en vooral Marx zijn collega's de gordijnen in jaagt en de volksmenner die op Wall Street een stel jongeren steunt en aanmoedigt en hen daarna lelijk te kakken zet. En misschien wel terecht, want wie op YouTube de beelden ziet van een orerende Zizek wiens woorden zin voor zin door de Occupiers nagescandeerd worden, kan bijna niet anders dan denken aan die scène uit Life of Brian waarin Brian zijn ongewenste volgelingen probeert weg te sturen met de boodschap dat ze voor zichzelf moeten denken en zij dit gewoon gedachteloos herhalen.

Beweren dat Zizek de John Cleese van de hedendaagse filosofie is, gaat misschien wat ver, maar grappig is hij ongetwijfeld. Hij is de nar die al schertsend de koning de waarheid zegt en zich zo verzekert van een miljoenenpubliek. Vorige week kreeg hij er een paar duizend van bij elkaar in de Brusselse Bozar, waar hij een lezing gaf over ons Europese erfgoed en het gesprek dat we nadien hadden kwam automatisch uit bij het lot van dit oude Avondland. "Wanneer je een Chinees alle kwaad van de wereld toewenst, zeg je: 'Dat je in interessante tijden moge leven.' Wel, vandaag leven we in interessante tijden. We kunnen kritiek hebben op wat er in West- Europa na de Tweede Wereldoorlog is verwezenlijkt, maar je moet de duivel uiteindelijk ook geven wat hem toekomt. Was er ooit een moment in de geschiedenis van de mensheid waarop zo veel mensen een vrij, welgesteld en veilig leven konden leiden? Het verontrustende is echter dat dit op zijn einde loopt. Neem nu het antifascistische pact dat de Europese democratische partijen vanzelfsprekend vonden, dat komt vandaag op de helling te staan. Je had vroeger ook extreemrechtse partijen, maar daar praatte je niet mee. In Oostenrijk en Nederland geldt die regel opeens niet meer en sluiten ze overeenkomsten met extreem rechts. En onze kijk op de geschiedenis wordt er ook door aangetast. Hitler is nog steeds des duivels, maar de vroege Franco of Mussolini, ho maar! Het enige wat zij deden was zich terecht verzetten tegen het communisme. Wij staan dus op het punt iets heel belangrijks overboord te gooien. En hier ga ik akkoord met Peter Sloterdijk wanneer hij zegt dat je een onderscheid moet maken tussen de sociaaldemocratie en sociaaldemocratische partijen. Na de oorlog werd de sociaaldemocratie iets vanzelfsprekends, ook voor christendemocratische en liberale partijen. Het deed er niet toe wie er aan de macht was, de sociaaldemocratie werd niet ter discussie gesteld. Ik vrees dat dit voorgoed voorbij is."

Is dit geen wereldwijd fenomeen? Uit de VS komt er ook al geen goed nieuws.

"Hoe raar het ook moge klinken, de meest linkse president die ze daar ooit hadden, was Richard Nixon. Na hem zijn onderwijs, cultuur, ziekenzorg en andere sociale programma's er alleen maar op achteruit gegaan. Zoals we in Griekenland en Italië op dit moment al kunnen zien, en misschien ook wel in Nederland, wacht Europa een pact tussen technocraten en antimigrantenrechts.

Weet je wat Lacan zei over jaloerse mannen? Dat hun jaloezie pathologisch is, ook al bedriegt hun vrouw hen aan alle kanten. Wat van belang is, is niet of de man gelijk heeft, maar waarom hij zo pathologisch gefixeerd is op dat overspel. Hetzelfde zie je vandaag met de angst voor moslims. Zelfs al zijn er inderdaad moslims die terroristische aanslagen voorbereiden, dat is het probleem niet. Dat ligt in de onmogelijkheid voor extreem rechts om een Europa op te bouwen dat zijn identiteit niet ophangt aan de oppositie tegen de islam. Vandaar mijn oproep om deze politiek van de angst achter ons te laten. Angst is vandaag de grote politieke hefboom geworden, ook voor links trouwens, die mensen bang maakt voor hervormingen. Niemand gelooft blijkbaar nog in een positieve visie op wat de toekomst zou kunnen zijn. Ik vind dat jammer."

Is dat geen teken dat onze beschaving in een crisis verkeert?

"Het enige wat politici vandaag beloven, is dat de boel zal blijven draaien. De fundamentele crisis van vandaag is dus niet economisch of politiek, maar wel spiritueel, en ik ben er mij van bewust dat dit een rare uitspraak is uit de mond van een marxist. Niet dat ik me tot het katholicisme heb bekeerd en de paus gelijk geef wanneer hij zegt dat we met een morele crisis te maken hebben geleid door hebzuchtige bankiers. Dat is gewoon dom, want wat zou een bankier anders moeten zijn dan hebzuchtig, dat is toch zijn job? Het probleem ligt bij ons systeem dat steunt op dit type bankiers. De paus bezondigt zich hier aan protofascistisch denken: het probleem ligt niet bij het systeem, maar bij die vuige bankiers, en als het een beetje meezit zijn het ook nog eens Joodse bankiers. Kijk naar de VS, waar alle schuld op de schouders van Bernie Madoff werd geschoven. Daar hebben we een corrupte Jood! Maar over de ondergang van Lehman Brothers werd gezwegen, terwijl Madoff in vergelijking maar een schooljongetje was. We moeten dus niet zitten zaniken dat het kapitalisme egoïstisch is, maar juist nog veel egoïstischer zijn. We moeten aan onszelf denken en aan onze toekomst."

De openlijke speculatie met voedsel lijkt wel het lelijkste gezicht van het kapitalisme.

"Zelfs Bill Clinton sprak zich uit tegen het economische neokolonialisme van vandaag, waarbij de vruchtbare gronden in ontwikkelingslanden verpacht worden aan firma's uit het Westen die er landbouwproducten verbouwen louter voor de export. Pas op, ik zeg niet dat we terug moeten naar een oubollige socialistische landbouwpolitiek. Dat was de grootste ramp die het socialisme ooit veroorzaakte. Zuidwestelijk Rusland en Oekraïne bezaten de vruchtbaarste landbouwgrond van heel de wereld. Oekraïne zou op zijn eentje heel Europa kunnen voeden. En toch diende de Sovjet-Unie vanaf de jaren zestig constant voedsel in te voeren. Daar moeten we dus zeker niet naar terug."

En wat met het argument dat het allemaal de schuld is van China, het land dat oneerlijk concurreert door de waarde van zijn munt kunstmatig laag te houden?

"De crisis van 2008 veroorzaakte in China op slag en stoot 13.000.000 werklozen, maar een paar maanden later waren die alweer aan de slag. Het autoritaire regime kon de banken verplichten geld te lenen met het doel de binnenlandse vraag aan te wakkeren en weg was de crisis. Voor mij is dit de donkere boodschap van de crisis: dat de democratie het op zo'n moment moet afleggen tegen om het even welk autoritair regime. We dachten altijd dat het kapitalisme enkel kon floreren onder een democratisch regime, maar dat is vandaag niet meer zo. De dictaturen fietsen ons lachend voorbij. Kijk naar het boegbeeld van de politiek autoritaire maar economisch ultraliberale praktijk, Singapore. In 2009, toen de crisis het zwaarst toesloeg, tekende dat land een economische groei van 15 procent op, een record. Ik vind dat verontrustend."

Is Chinese democratie denkbaar?

"China heeft geen nood aan meer politieke partijen, maar wel aan een vrije samenleving, met ecologische drukkingsgroepen en onafhankelijke vakbonden. In het China van vandaag kun je gerust de vloer aanvegen met Marx. Niemand geeft nog om die ouwe troep. Maar wanneer je een staking probeert op te zetten, ben je - poef - zo maar opeens verdwenen. Iedere samenleving heeft zijn heilig boek en in China is dat De geschiedenis van de Communistische Partij. In de laatste editie bleek een bepaalde paragraaf opeens weg. Het gekke is dat die paragraaf heel lovend was voor de Partij. Hij ging over de jaren dertig, net voor de Japanse invasie, toen de streek rond Shanghai een economische boom beleefde en de Communistische Partij arbeiders verenigde in vakbonden. Stel dat dit mensen op ideeën brengt, dacht men wellicht, en dus ging die paragraaf eruit. Kijk, ik ben geen catastrofist die het einde van de wereld verkondigt. Ik doe niet meer dan de crisis serieus nemen en beweren dat het tijd wordt om na te denken over een alternatief voor het kapitalisme."

En wat is dat alternatief?

"Zeker niet het oude communisme, want dat is zo dood als een pier, en de sociaaldemocratische welvaartsstaat wellicht ook. In de twintigste eeuw wisten we wat we moesten doen, maar we wisten niet hoe. Vandaag zitten we met het tegenovergestelde probleem: we zien dat we iets moeten doen, maar we weten niet wat. Iemand vroeg me ooit waarom ik alleen kritiek heb en geen oplossingen aandraag. 'Waarom gun je ons geen blik op het licht aan het einde van de tunnel?', vroeg hij. Dus gaf ik hem het perfecte Oost-Europese antwoord: 'Dat doe ik liever niet aangezien het licht aan het einde van de tunnel afkomstig is van een andere trein die aan topsnelheid op ons afkomt.' Ik vind al die oplossingen zo goedkoop dramatisch: je beschrijft een probleem en op het einde bied je de oplossing. Zo makkelijk is het, maar wat als er geen hoop is? Volgens mij is de eerste stap naar een oplossing het besef dat er geen makkelijke hoop is. In dit leven kun je alleen maar pessimistisch zijn, vind ik. Dat is de enige manier om nog af en toe ook gelukkig te zijn, want optimisten worden constant teleurgesteld".

Maar toch blijft u streven naar een nieuw soort communisme?

"Waarom doe je dat Slavoj, vragen mijn vrienden, want je weet toch dat iedereen bij het horen van de term communisme meteen aan de stalinistische goelag denkt? Precies, antwoord ik dan, ik gebruik communisme omdat alle andere termen bezwaard geraakt zijn. Neem socialisme, iedereen is tegenwoordig toch socialist? Zelfs Hitler was er een. Socialisme staat immers voor een soort gemeenschappelijke solidariteit, waardoor het niet meer is dan gegeneraliseerd kapitalisme. Wie heeft in Amerika in 2008 de banken gered? Inderdaad, links, want rechts wou ze failliet laten gaan. Zonder socialisme hadden we vandaag misschien zelfs geen kapitalisme meer. Voor mij is communisme eerder de naam van een probleem, niet van de oplossing. Met het nieuwe communisme bedoel ik een manier om zinvol om te springen met al onze gemeenschappelijke goederen."

Bron: De Morgen, 7 december 2011, pp. 33-35

00:07 Publié dans Philosophie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : slovénie, slavoj zizek, philosophie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

A Guerra como Experiência Interior

"Para o soldado - escreve Philippe Masson em L'Homme en Guerre 1901-2001 - para o verdadeiro combatente, a guerra se identifica com estranhas associações, uma mescla de fascinação e horror, humor e tristeza, ternura e crueldade. No combate, o homem pode manifestar covardia ou uma loucura sanguinária. Encontra-se sujeito entre o instinto pela vida e o instinto mortal, pulsões que podem lhe conduzir à morte mais abjeta ou ao espírito de sacrifício.

"Para o soldado - escreve Philippe Masson em L'Homme en Guerre 1901-2001 - para o verdadeiro combatente, a guerra se identifica com estranhas associações, uma mescla de fascinação e horror, humor e tristeza, ternura e crueldade. No combate, o homem pode manifestar covardia ou uma loucura sanguinária. Encontra-se sujeito entre o instinto pela vida e o instinto mortal, pulsões que podem lhe conduzir à morte mais abjeta ou ao espírito de sacrifício.

00:05 Publié dans Littérature, Militaria, Révolution conservatrice | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : allemagne, révolution conservatrice, ernst jünger, première guerre mondiale, littérature, lettres, lettres allemandes, littérature allemande, militaria |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

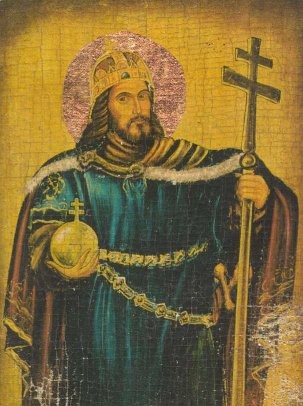

Hongrie : le soleil se lèverait-il à l’Est ?

Par Claude Bourrinet

Ex: Vox NR cliquez ici

Attila serait-il de retour au pays des Huns et des Onoghours (Hungari en latin) ? Le royaume du roi Istvàn, converti au christianisme sous le nom, vénéré par les Magyars, de Saint-Etienne, va-t-il semer la pagaïe dans une Europe devenue un véritable capharnaüm, et qui, pour le coup, ne sait plus à quel saint se vouer, sinon au marché international ?

Attila serait-il de retour au pays des Huns et des Onoghours (Hungari en latin) ? Le royaume du roi Istvàn, converti au christianisme sous le nom, vénéré par les Magyars, de Saint-Etienne, va-t-il semer la pagaïe dans une Europe devenue un véritable capharnaüm, et qui, pour le coup, ne sait plus à quel saint se vouer, sinon au marché international ?

A entendre tel ou tel, par exemple notre Juppé, qui, revenu des froids canadiens à la suite d’une affaire très chaude bien connue de Chirac, se montre depuis quelque temps un serviteur zélé de l’oligarchie transnationale, et s’esclaffe : « Il y a un problème en Hongrie », ou bien, de façon beaucoup moins cocasse, cette déclaration d’un diplomate américain, dont on se demande bien (naïvement) de quoi il se mêle : « L’exclusion de la Hongrie de l’Union européenne n’est plus impensable », propos qui révèlent en passant qui est le vrai maître, à constater l’hystérie de médias qui se sont fait une spécialité de déformer la réalité, de manipuler l’opinion et d’escorter les manœuvres sournoises des services d’espionnage et de déstabilisation de nations qui ont le tort d’aspirer à la maîtrise de leur destin, on se dit qu’un tremblement géopolitique est imminent, et qu’il n’est pas exclu, comme au Kossovo, en Libye etc. qu’ il soit suivi du feu du ciel. Ainsi vont les choses dans notre douce démocratie occidentale, bercée par le ronronnement rassurant de droits de l’homme souples à souhait.

La promulgation, le premier janvier 2012, de la nouvelle Constitution hongroise, a semé la panique parmi les bureaucrates de Bruxelles. Ne clame-t-elle pas : « Nous sommes fiers de nos ancêtres qui se sont battus pour la survie, la liberté et la souveraineté de notre nation » ? Voilà des accents mâles qui, en effet, risquent de faire pâlir les ouvriers de notre nouvelle Tour de Babel. On notera au passage que le préambule de cette constitution se réclame de l’Europe, mais probablement n’est-ce pas la même que celle qui, actuellement, sert d’antichambre à la dictature mondiale qu’on voudrait bien nous imposer.

La Constitution hongroise nouvelle formule change radicalement la manière de concevoir et l’Histoire, et la politique. En répudiant l’appellation « République de Hongrie » au profit de « Hongrie » tout court, le FIDESZ (Union civique hongroise) de Viktor Orban veut non seulement rendre la nation au peuple, en considérant comme secondaire la question du régime adopté, mais inscrit aussi son destin dans un passé mythifié, au sens sorélien, en se référant notamment à des emblèmes de l’Histoire hongroise, comme le roi Etienne et la doctrine de la sainte Couronne. Le christianisme est revendiqué comme le cœur de la patrie, ce que maints Tartuffes ont condamné, occultant non seulement ce que clame la Constitution américaine, qui demande à Dieu de bénir l’empire de l’Oncle Sam, mais aussi ce que postule l’Etat sioniste, à savoir qu’il est un Etat juif. Apparemment, il y aurait des « vérités » approuvées au-delà, et des « mensonges » réprouvées en-deçà.

Les politiques intérieure et extérieure de l’Union européenne sont depuis une décennie devenues un protocole judiciaire, criminalisant les récalcitrants, machine à broyer incarnée par le TPI. Nul doute que l’on trouvera, à terme, un prétexte pour traîner les responsables hongrois devant une justice aux ordres. Déjà, comme si ces points de détail constituaient l’alpha et l’oméga d’une existence digne d’être vécue, on met en exergue la volonté de ces voyous de s’en prendre au mariage homoparental et au droit à l’avortement, et, le comble, de « restaurer un certain ordre moral », prétention qui confine sans doute pour nos censeurs post-soixante-huitards, au crime suprême. Car l’idéologie de la grosse classe petite-bourgeoise internationale est devenue dogme, donc inquisitoriale. Au-delà, nul salut !

Une mesure qui gêne est sans doute aussi celle qui rejette toute prescription des crimes contre l’humanité commis par le nazisme, mais aussi par les anciens communistes. Il est nécessaire de ramener à la mémoire un passé assez proche, et pas seulement celui qui rappelle les événements d’octobre 56, révolte nationale contre l’empire soviétique qui, soit dit en passant, ne put être écrasée qu’avec l’assentiment des Occidentaux. La mesure vise en fait une classe politique honnie, méprisée, défaite totalement aux dernières élections, cette caste-même qui est soutenue pas l’Union européenne, ce ramassis de staliniens reconvertis en doux agneaux libéraux, en champions du mondialisme et de l’économie de marché. Nous connaissons cette espèce, nous aussi, en France, parmi une gauche bienpensante et bien conformée aux desiderata de l’oligarchie financière. Or il se trouve que ces sociaux-démocrates avaient ruiné le pays, à force d’emprunts inconsidérés. On connaît la musique, et les taux d’intérêt astronomiques, la pression des banques, les combinaisons internationales et les abdications nationales subséquentes. La Grèce et l’Italie, sans compter d’autres pays, sont là pour illustrer une manœuvre qui est trop belle pour n’avoir été calculée savamment. Or, les Hongrois ont dit non, en renationalisant par exemple la banque centrale hongroise !

L’étincelle qui a mis le feu aux poudres fut cette déclaration « off » du 14 juin 2006, intempestive, désastreuse, à vomir, de l’ancien Premier ministre Ferenc Gyunasàny, dont nous reproduisons le texte d’un cynisme qui jette une lueur significative sur ce que sont nos dirigeants (car on ne fera pas l’injure aux nôtres d’être assez mous pour ne pas partager l’amoralisme de gens qui, au demeurant, s’enorgueillissent de donner des leçons aux peuples…). Des émeutes s’en s’ont suivies, et le bouleversement politique, la révolution (car c’en est une) que nous connaissons.

Certains commentateurs remarquent qu’il ne subsiste plus de « gauche » en Hongrie. La politique menée par le « Parti Socialiste hongrois », qui a recyclé les ancien apparatchiks en hommes d’affaires, prouve suffisamment, s’il en était encore besoin, qu’il n’existe, qu’il ne peut plus exister, ni de gauche, et, partant, ni de droite, mais plutôt une caste oligarchique internationale contre des peuples dépossédés de leur identité et bafoués dans leurs intérêts. C’est justement un mouvement, une insurrection légale qui s’est produite en Hongrie, une réappropriation par le peuple hongrois de son corps et de son âme.

Quel sera l’avenir de ce sursaut ? Il semble évident que les USA et leur commis, l’Union européenne, ne resteront pas sans réagir, bien qu’il y ait péril en la demeure, et que le feu puisse se répandre. Car trop de pression risquerait de produire l’effet inverse. Des rétorsions sournoises, malhonnêtes, et des charretées de calomnies, d’injures et de propagande vont sans doute continuer à assaillir ce peuple valeureux. Pour celui-ci, un certain nombre de défis gigantesques sont à relever, dont l’endettement et l’isolement, et probablement la réinsertion identitaire de Hongrois de souche, un tiers de la population totale, dispersés, à la suite du traité inique du Trianon, en 1919,dans les pays voisins, en Slovénie, en Roumanie, en Slovaquie, en Serbie, en Ukraine, en Autriche - sans qu’éclate un conflit toujours latent en Europe centrale. Il est bien dommage que subsiste un contentieux très lourd avec la Russie. D’un point de vue intérieur, il est évident que le parti majoritaire n’a pas intérêt à agresser le pari Jobbik qui, ne cessant de grandir, apparaît comme la partie la plus active du mouvement national. Il est sûr, en tout cas, que tous les regards désabusés, écœurés par la marche des choses en Europe, vont se fixer sur l’expérience hongroise. Son succès retentira comme un gage d’espoir pour les patriotes.

Traduction des propos de M. Ferenc Gyurcsany :

« Nous n'avons pas le choix. Il n'y en a pas parce qu'on a merdé sur toute la ligne. Pas un petit peu, beaucoup. En Europe, il n'y a pas d'autre pays où on aurait commis de telles conneries Il est possible de l'expliquer... De toute évidence, nous n'avons pas arrêté de mentir sur tout et dans les grandes largeurs au cours des derniers 18 à 24 mois. Il est clair que pas un seul de nos propos n'était vrai. Nous avons dépassé les possibilités du pays de sorte que (...) nous ne pouvions imaginer plus tôt que la coalition du Parti Socialiste Hongrois et des libéraux aille jusque là. Et pendant ce temps-là, nous avons réussi à ne rien foutre du tout pendant quatre ans. Pas une rame ! Pas une seule mesure gouvernementale importante ne me vient à l'esprit dont nous pourrions être fiers, outre que nous avons au bout du compte tiré le gouvernement de la merde. Rien d'autre. Que va-t-on dire s'il faut expliquer au peuple ce que nous avons foutu. pendant quatre ans ?! »...

[....]

« Moi, je pense qu'il est possible de mettre tout ça en œuvre. Je pense qu'il y aura des conflits, oui, mes amis. Il y aura aussi des manifs. Il est bien permis de manifester devant le Parlement ; tôt ou tard, les manifestants s'en lasseront, et ils rentreront chez eux. Il n'est possible d'aboutir que si vous avez foi dans l'essentiel, et si on est d'accord sur l'essentiel en question ».

[...]

« Ce que nous pouvions faire au cours du mois écoulé, nous l'avons fait. Et ce que nous avons pu faire en secret les mois précédents pour éviter de voir sortir de nulle part les derniers jours de la campagne des papiers révélant ce que nous avions l'intention de faire, ce que nous nous préparions à faire, nous l'avons fait aussi. Nous avons gardé le secret, et nous savions, comme vous le saviez vous-même, que nous si nous gagnions les élections, il s'agirait ensuite de se relever les manches et de s'y mettre, parce que nous n'avons jamais été confrontés à des problèmes de ce genre...".

00:05 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : politique internationale, actualité, europe, affaires européennes, hongrie, europe centrale, mitteleuropa, europe danubienne |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Par Marc Rousset

Chômage des travailleurs européens ou profits des multinationales dans les pays émergents fournissant des produits manufacturés à l’Europe : il va falloir choisir ! Sinon la révolte éclatera d’une façon inéluctable lorsque le taux de chômage sera tellement insupportable que la folie libre échangiste mondialiste apparaitra comme un nez au milieu de la figure ! Pour l’instant nous sommes seulement à mi-chemin de la gigantesque entreprise de désindustrialisation initiée dans les années 1950 aux Etats-Unis pour favoriser les grandes entreprises américaines, et dont le flambeau a été depuis repris par toutes les sociétés multinationales de la planète ! Pendant ces 30 dernières années, la France a perdu 3 millions d’emplois industriels, l’une des principales raisons de la crise de notre dette souveraine ! Si un protectionnisme douanier ne se met pas en place d’une façon urgente, les choses vont encore aller en s’accélérant ! L’oligarchie mondiale managériale, actionnariale et financière a des intérêts en totale contradiction et en opposition frontale avec le désir des peuples européens de garder leur « savoir faire » et leur emploi !

L’usine géante Renault de Melloussa au Maroc

Alors que la production automobile de Renault recule dans l’hexagone, l’usine géante de Melloussa au Maroc dans la zone franche du port de Tanger, avec une capacité de 340 000 véhicules par an, commence à produire des voitures « low-cost » sous la marque Dacia. Le site a pour vocation d’exporter à 85% vers le Vieux Continent. Cette usine marocaine vient s’ajouter au site roumain de Pitesti qui produit 813 000 voitures par an. Renault et les équipementiers de la région de Tanger pourraient créer 40 000 emplois ! Le salaire net mensuel d’un ouvrier marocain est de 250 euros par mois, contre 446 euros par mois en Roumanie. Le coût salarial horaire d’un ouvrier dans les usines Renault est de 30 euros /heure en France, 8 euros par heure en Turquie, 6 euros par heure en Roumanie et ô surprise 4,5 euros par heure au Maroc, à deux jours de bateau des côtes françaises, Algésiras en Espagne étant seulement à 14km ! C’est la raison pour laquelle le monospace « Lodgy 5 ou 7 places » (10 000 euros) fabriqué à Melloussa sera deux fois moins cher que le Renault Grand Scenic (24 300 euros) assemblé à Douai. Il ne fait donc aucun doute qu’à terme, suite au rapport qualité/ prix et en faisant abstraction de quelques gadgets Marketing et des dénégations du Groupe Renault, les consommateurs français, s’ils ne sont pas trop bêtes, achèteront des Lodgy fabriquées au Maroc en lieu et place des Grand Scenic fabriquées à Douai ! Bref, une délocalisation élégante supplémentaire avec les miracles et les mensonges de la Pub et du Marketing comme paravent !

Alors que faire ? Qui incriminer ? Certainement pas Carlos Ghosn et les dirigeants de Renault qui font parfaitement leur travail avec les règles du jeu actuel, car ils rendent compte à leurs actionnaires et doivent affronter une concurrence terrible, la survie du Groupe Renault étant même en jeu s’ils ne délocalisent pas ! Non, les responsables, ce sont nous les citoyens, nous les électeurs, qui acceptons cette règle économique du jeu ;les principaux coupables, ce sont nos hommes politiques incapables, gestionnaires à la petite semaine avec un mandat de 5 ans, subissant les pressions du MEDEF et des médias à la solde des entreprises multinationales. Les dirigeants d’entreprise et les clubs de réflexion qui mentent comme ils respirent, le MEDEF, tout comme le lobby des affaires à Washington et à Bruxelles, voilà ceux qui sont à l’origine du mal et nous injectent délibérément car conforme à leurs intérêts financiers, le virus, le venin destructeur malfaisant du libre échangisme mondialiste dans nos veines ! Le mondialisme doit laisser sa place d’une façon urgente à un libre échangisme strictement européen ! Les hommes politiques des démocraties occidentales ne sont pas des hommes d’Etat, mais des gagneurs d’élection et ne voient pas plus loin que le bout de leur nez ; ils ne s’intéressent en aucune façon aux intérêts économiques à long terme de la France et de l’Europe ! Ils attendent tout simplement la catastrophe du chômage structurel inacceptable et la révolte des citoyens pour réagir, comme cela a été le cas en Argentine et comme c’est le cas actuellement avec la crise des dettes souveraines.

Les idées de la préférence communautaire et du Prix Nobel Maurice Allais triompheront

Les idées de Maurice Allais triompheront car elles sont justes et correspondent aux tristes réalités que nous vivons ! On ne peut pas arrêter une idée lorsqu’elle est juste ! L’idéologie économique libre échangiste mondialiste s’écroulera totalement devant les réalités du chômage, comme le Mur de Berlin en raison de l’inefficacité du système soviétique, comme l’idéologie droit de l’hommiste devant les réalités néfastes de l’immigration extra-européenne avec à terme les perspectives d’une guerre civile ! Il est clair qu’il faut changer le Système, non pas en attendant la disparition totale de notre industrie, mais dès maintenant en mettant en place tout simplement des droits de douane au niveau européen! Même l’Allemagne ne réussira pas à terme à s’en sortir avec le libre échange mondialiste. Elle résiste encore aujourd’hui car elle n’a pas fait les mêmes bêtises que les autres pays européens, mais à terme elle sera également laminée par la montée en puissance de l’éducation et le trop bas coût de la main d’œuvre dans les pays émergents. Aux Européens de savoir préserver les débouchés de leur marché domestique suffisamment grand pour assurer un minimum d’économies d’échelle! La « théorie des débouchés » va très vite revenir à l’ordre du jour !

La vieille théorie des « avantages comparatifs »de Ricardo n’a plus grand-chose à voir avec la réalité. Pour la première fois dans l’histoire du monde, des Etats (la Chine, l’Inde et le Brésil) vont en effet posséder une population immense ainsi qu’une recherche et une technologie excellentes. L’égalisation par le haut des salaires, selon la théorie de Ricardo, n’ira nullement de soi du fait de « l’armée de réserve » rien qu’en Chine de 750 millions de ruraux, soit 58% de l’ensemble de la population, capables de mettre toute l’Europe et les Etats-Unis au chômage. 300 millions d’exclus vivent, selon la Banque asiatique du développement, dans l’Empire du milieu, avec moins d’un euro par jour. La Chine ne se classe qu’au 110e rang mondial du PIB par habitant. Ce ne sont pas quelques succès épars européens mis en avant par les médias, suite à des effets de mode ou de luxe, qui doivent nous faire oublier le tsunami du déclin des industries traditionnelles en Europe (quasi disparition des groupes Boussac, DMC et de l’industrie textile dans le Nord de la France, de l’industrie de la chaussure à Romans, de l’industrie navale, des espadrilles basques...). Les pays émergents produiront inéluctablement de plus en plus, à bas coût, des biens et des services aussi performants qu’en Europe ou aux Etats-Unis. Les délocalisations deviennent donc structurelles et non plus marginales !

L’épouvantail contre le protectionnisme mis en avant par les lobbys du MEDEF et des multinationales comme quoi 25% des Français travaillent pour l’exportation est un mensonge d’Etat parfaitement mis en avant par Gilles Ardinat d’une façon indiscutable dans le dernier Monde Diplomatique. Les multinationales, le MEDEF confondent délibérément valeur ajoutée et chiffre d’affaires des produits exportés, ce qu’il fait qu’ils arrivent au ratio fallacieux de 25%. La Vérité est qu’un salarié français sur 14 seulement vit pour l’exportation en France ! (1)

Dans un système de préférence communautaire, l’Europe produirait davantage de biens industriels et ce que perdraient les consommateurs européens dans un premier temps en achetant plus cher les produits anciennement « made in China », serait plus que compensé par les valeurs ajoutées industrielles supplémentaires créées en Europe . Ces dernières augmenteraient le PIB et le pouvoir d’achat, tout en créant des emplois stables et moins précaires, système que la CEE a connu et qui fonctionnait très bien. Alors, au lieu de s’en tenir au diktat idéologique de Bruxelles et au terrorisme intellectuel anglo-saxon du libre échange, remettons en place le système de la préférence communautaire !

Les investissements occidentaux et les délocalisations

Il importe de faire la distinction entre marché domestique européen intérieur et marché d’exportation. Ce qu’il faut, c’est, grâce à une politique douanière de préférence communautaire fermer l’accès aux pays émergents qui détruisent les emplois européens pour des produits consommés sur le marché intérieur européen.

Il n’est pas réaliste d’accepter le dogme stupide que délocaliser la production physique d’un bien ne représente qu’une infime partie de sa valeur, même s’il est inéluctable que le poids relatif de l’Occident continue à décliner au profit de l’Asie. Intégristes du tout marché et théoriciens d’un libéralisme de laboratoire se délectent du déclin de la France et des Etats-Nations ; complices ou naïfs, ces inconscients nous emmènent à la guerre économique comme les officiers tsaristes poussaient à la bataille de Tannenberg des moujiks armés de bâtons. Les Européens ne peuvent se contenter d’une économie composée essentiellement de services. La seule façon de s’en sortir pour tous les pays européens, et plus particulièrement la France, est de réduire d’une façon drastique le nombre des fonctionnaires et les dépenses publiques, diminuer la pression fiscale sur les entreprises et les particuliers, mettre en place une politique industrielle inexistante à l’échelle de l’Europe, développer la recherche et l’innovation, encourager le développement des jeunes pousses, favoriser le développement des entreprises moyennes, et enfin restaurer la préférence communautaire avec des droits de douane plus élevés ou des quotas afin de compenser les bas salaires des pays émergents !

Le problème de fond du déficit commercial de la France n’est pas lié au taux de change de l’euro, mais au coût du travail. Le coût horaire moyen de la main d’œuvre dans l’industrie manufacturière est de l’ordre de vingt dollars en Occident contre 1 dollar en Chine ! Un ouvrier en Chine travaille quatorze heures par jour, sept jours sur sept. 800 millions de paysans chinois dont deux cents millions de ruraux errants forment une réserve de main d’œuvre inépuisable capable de mettre les Etats-Unis et toute l’Europe au chômage, nonobstant la main d’œuvre tout aussi nombreuse d’autres pays émergents !

Attirés par les bas salaires, les investissements étrangers en Chine s’élèvent à plus de 100 milliards de dollars par an, soit davantage qu’aux Etats-Unis. Le fait que les exportations chinoises soient réalisées à 65% par des entreprises détenues totalement ou partiellement par des Occidentaux n’est qu’un argument de plus pour nous endormir et une étape intermédiaire dans le déclin programmé du continent paneuropéen et de l’Occident. Les seuls investissements justifiés géopolitiquement sont les implantations pour s’intéresser au marché domestique chinois, des autres pays d’Asie et de tous les pays émergents. Ce qu’il faut bien évidemment combattre, ce sont avant tout les investissements européens en Chine ou ailleurs pour alimenter le marché européen qui sont suicidaires mais justifiés pour les chefs d’entreprise, tant que les Européens et la Commission de Bruxelles n’auront pas rétabli la préférence communautaire et des droits de douane afin de compenser les bas coûts de main d’œuvre chinois, source première du chômage et de la précarité en Europe.

Conclusion

Il ne faut pas acheter français, ce qui ne veut plus rien dire, mais acheter « fabriqué en France » en se méfiant des noms francisés et des petits malins avec des usines tournevis ou d’assemblage dont toute la valeur ajoutée industrielle viendrait en fait des pays émergents ! Seule une politique de droits de douane défendra l’emploi du travailleur européen et combattra efficacement d’une façon implacable le recours démesuré aux sous-traitants étrangers ! Tout cela est si simple, si clair, si évident qu’il nous manque qu’une seule chose, comme d’habitude, dans notre société décadente : le courage ! Le courage de changer le Système, le courage de combattre les lobbys des entreprises multinationales avec les clubs de réflexion à leur botte, le courage de mettre en place une protection tarifaire, mais sans tomber pour autant dans le Sylla du refus de l’effort, de l’innovation, du dépassement de soi, du refus de s’ouvrir au monde et de tenter d’exporter autant que possible, le Sylla de l’inefficacité et des rêveries socialistes utopistes qui refusent la concurrence et l’efficacité intra-communautaire. L’introduction de la TVA sociale est une excellente décision, mais elle est totalement incapable de compenser les bas salaires de l’usine marocaine Renault de Mélissa et ne vaut que pour améliorer la compétitivité de la Maison France par rapport aux autres pays européens !

Note

(1) Gilles Ardinat, Chiffres tronqués pour idée interdite, p12, Le Monde Diplomatique, Janvier 2012.

00:05 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes, Economie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : globalisation, économie, délocalisations, renault, martoc, europe, affaires européennes, afrique, afrique du nord, affaires africaines |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Ex: http://freigeist-blog.blogspot.com/

In der Nacht vom 1. auf den 2. Jänner 2012 verstarb Nationalratsabgeordneter a.D. Dr. Otto Scrinzi im 93. Lebensjahr in seinem Heimatbundesland Kärnten. Mit Otto Scrinzi ist einer der letzten Gründerväter des Dritten Lagers der Zweiten Republik von uns gegangen. Unmittelbar nach der Heimkehr aus der Kriegsgefangenschaft stellte er sich neben seiner Arbeit als Facharzt in den Dienst des staatlichen Gemeinwesens. So begründete der 1918 in Osttirol geborene Scrinzi in seiner nunmehrigen Heimat Kärnten den Verband der Unabhängigen (VDU) mit, wurde dessen Landesobmann und vertrat den VDU 1949 bis 1956 im Kärntner Landtag als Abgeordneter und Klubobmann. Neben seiner landespolitischen Tätigkeit setzte er sich auch als Standesvertreter für die Belange der Kärntner Ärzteschaft ab 1949 ein.

In der Nacht vom 1. auf den 2. Jänner 2012 verstarb Nationalratsabgeordneter a.D. Dr. Otto Scrinzi im 93. Lebensjahr in seinem Heimatbundesland Kärnten. Mit Otto Scrinzi ist einer der letzten Gründerväter des Dritten Lagers der Zweiten Republik von uns gegangen. Unmittelbar nach der Heimkehr aus der Kriegsgefangenschaft stellte er sich neben seiner Arbeit als Facharzt in den Dienst des staatlichen Gemeinwesens. So begründete der 1918 in Osttirol geborene Scrinzi in seiner nunmehrigen Heimat Kärnten den Verband der Unabhängigen (VDU) mit, wurde dessen Landesobmann und vertrat den VDU 1949 bis 1956 im Kärntner Landtag als Abgeordneter und Klubobmann. Neben seiner landespolitischen Tätigkeit setzte er sich auch als Standesvertreter für die Belange der Kärntner Ärzteschaft ab 1949 ein.

| . |

Nicht bequem, dafür aber immer prinzipientreu

So konsequent er die Finger in die Wunden der Regierungspolitik von Rot und Schwarz legte, so konsequent mahnte er auch im eigenen politischen Lager Prinzipientreue ein. Als es in der FPÖ in Zeiten einer rot-blauen Koalition 1983 bis 1986 kurzzeitig ein Liebeugeln mit dem FDP-Modell gab, stellte er sich als Präsidentschaftskandidat der „National-Freiheitlichen Aktion“ 1986 zur Verfügung und leitete damit wiederum eine Rückkehr zu einer echten freiheitlichen Politik in der FPÖ ein. Als Funktionsträger im Freiheitlichen Akademikerverband sowie Herausgeber, Schriftleiter und Autor des Magazins Die Aula nahm er in 5 Jahrzehnten in vielfältiger Weise zu gesellschaftspolitischen Grundsatzfragen, jenseits der Tagespolitik Stellung. Mit Otto Scrinzi verliert nicht nur die freiheitliche Gesinnungsgemeinschaft einen geschätzten Repräsentanten und Weggefährten, sondern darüber hinaus Österreich einen Politiker, der stets für die Gemeinschaft, und niemals für den Eigennutz eingestanden ist.Bundesparteiobmann HC Strache würdigte den FPÖ-Gründervater: „Scrinzi war jemand, den man mit Fug und Recht als freiheitliches Urgestein bezeichnen konnte und der die Werte unserer Gesinnungsgemeinschaft immer gelebt hat."

15:57 Publié dans Actualité, Hommages | Lien permanent | Commentaires (1) | Tags : nécrologie, autriche, europe, affaires européennes, europecentrale, europe alpine, mitteleuropa |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

En la noche del 1 al 2 de enero de 201,1 Otto Scrinzi murió a la edad de 93 años. Neurólogo, escritor y político. Nacido en 1918 en Lienz en el Tirol (que no debe confundirse con Linz), estudió en Innsbruck, Riga, Königsberg y Praga. Fue miembro del NSDAP (número 7.897.561) y el Sturmführer SA Durante la guerra fue ayudante en el Instituto de Biología y Genética de la Universidad racial de Innsbruck. Desde 1950 ejerció como neurólogo y, desde 1955 a 1983, fue director médico del departamento de psiquiatría del hospital de Carintia en Klagenfurt. En 1973, ocupó una cátedra en la Universidad de Graz. De 1949 a 1956, Otto Scrinzi es parlamentario por el VdU (origen del FPÖ) en el Parlamento de Carintia. En 1968, es elegido vicepresidente del FPÖ. Desde marzo de1966 hasta junio de 1979, Otto Scrinzi es diputado del FPÖ en el Parlamento nacional, también es portavoz del FPÖ para el Tirol del Sur (Italia), en 1977 se convierte en vicepresidente del grupo de electos del FPÖ en el Parlamento nacional.

En 1984 funda la Nacional Freiheitliche-Aktion (NFA) como la oposición a la política encabezada por el presidente del FPÖ Norbert Steger, al que considera demasiado liberal. En 1986, se presenta por la NFA como candidato a las elecciones presidenciales y logra un 1,2% (Kurt Waldheim gana las elecciones y se convierte en Presidente de la República de Austria). Tras la llegada de Jörg Haider a la presidencia del FPÖ en 1986, Otto Scrinzi regresa al partido, convirtiéndose desde entonces en uno de los representantes del sector más radical del partido.

El presidente del FPÖ, Heinz-Christian Strache, se ha manifestado profundamente conmovido por la muerte de Otto Scrinzi y lo describió como un luchador por las ideas del FPÖ desde el primer momento, señalando que “siempre ha vivido los valores de nuestra comunidad de pensamiento. Añadiendo que su recuerdo será imborrable para el que lo que él ha hecho por el FPÖ siempre será inolvidable.

También hizo llegar sus condolencias el presidente del FPK (partido mayoritario en Caritnia y aliado del FPÖ), Uwe Scheuch, quien dijo que con su muerte la comunidad política nacionalistas ha perdido uno de los mejores compañeros de las últimas décadas.

La Schützenbund Südtiroler (Unión para la protección del Tirol del Sur) también ha rendido el merecidohomenaje a Otto Scrinzi.

15:47 Publié dans Actualité, Hommages | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : autriche, europe, affaires européennes, europe centrale, mitteleuropa, europe alpine |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

15:33 Publié dans Actualité, Hommages | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : autriche, europe, affaires européennes, europe alpine, mitteleuropa, europe centrale, otto scrinzi |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

MOOSBURG – In der Nacht vom 1. auf den 2. Jänner 2012 ist in Kärnten ein Mann verstorben, dem Südtirol viel zu verdanken hat. Der österreichische Primar und Nationalratsabgeordnete a.D. Dr. Otto Scrinzi war 93 Jahre alt geworden. Er hatte ein erfülltes Leben hinter sich, welches von der Liebe zu Südtirol und von selbstlosem Einsatz für Volk und Heimat geprägt war. Scrinzis Südtiroler Eltern hatte es 1918 nach Lienz verschlagen. Der junge Bursch verbrachte seine Schulferien zumeist bei den Großeltern in Branzoll bei Bozen und in Petersberg. Er half während der Faschistenzeit seinem Onkel, einem aus dem Schuldienst entlassenen Lehrer, bei der Durchführung des heimlichen deutschen Schulunterrichts.

Scrinzi trug zusammen mit Freunden deutsche Bücher über die Berge nach Südtirol und half bei dem Aufbau der „Katakombenschulen“ mit. Als in Österreich in der Zeit des Ständestaates die Demokratie abgeschafft wurde und die Staatsführung mit Mussolini paktierte, schloss sich der junge Innsbrucker Student Scrinzi den illegalen Nationalsozialisten an.

Wie viele seiner Landsleute erwartete auch Scrinzi, dass dem Anschluss Österreichs die Befreiung Südtirols folgen würde. Diese Hoffnung wurde durch den Pakt Hitlers mit Mussolini und durch das schreckliche Optionsabkommen bitter enttäuscht. Ein innerer Bruch mit der NS-Parteilinie war die Folge. Als Leiter des karitativen „Reichsstudentenwerkes“ in Innsbruck vergab Otto Scrinzi Förderungen an Südtiroler Studenten, verbunden mit der Auflage, nicht für Deutschland zu optieren, sondern in Südtirol zu verbleiben. Zu den derart Geförderten gehörte auch der spätere SVP-Politiker Friedl Volgger.

Durch diese und ähnliche Tätigkeiten geriet Otto Scrinzi in das Visier der Gestapo, Einvernahmen und auch einige Tage Haft waren die Folge. Seine Einrückung zur Wehrmacht nach seiner Promotion zum Doktor der gesamten Heilkunde rettete ihn vor weiterer Bespitzelung und Verfolgung.

Als Truppenarzt diente Dr. Scrinzi auf dem Balkan und an der Eismeerfront, um nach dem Krieg Primararzt in Kärnten, Landtagsabgeordneter und 1966 Nationalratsabgeordneter und Südtirolsprecher der Freiheitlichen Partei Österreichs zu werden. Weitere politische Funktionen: Mitglied in der Beratenden Versammlung des Europarates, Delegationsmitglied bei den Vereinten Nationen.

In einer großen parlamentarischen Rede wies Scrinzi im Jahre 1969 darauf hin, dass die „Paket“-Autonomielösung schwerwiegende Mängel aufwies: Von dem Fehlen einer einklagbaren Verankerung bis hin zur ungelösten Ortsnamensfrage. Die weitere Entwicklung hat der damaligen Kritik des Abgeordneten Scrinzi Recht gegeben.

Auch nach seinem Ausscheiden aus der aktiven Politik blieb Dr. Scrinzi seiner Heimat Südtirol verbunden. Als Kurator der „Laurin-Stiftung“, der nach Einstellung der „Stillen Hilfe“ größten Südtirol-Stiftung, half Dr. Scrinzi Jahrzehnte hindurch, Hunderte von Bauernhöfen und gewerblichen Betrieben durch großzügige Umschuldungen aus unverschuldeten Notlagen zu retten.

Dazu kamen kulturelle Förderungen, die Dorfgemeinden, kirchlichen Organisationen, Schützenkompanien, Musikkapellen und Vereinen zugute kamen.

Ein besonderer Schwerpunkt war die Schaffung und Dotierung von Assistentenstellen und die Vergabe von Stipendien für Südtiroler an der Innsbrucker Universität. Auch Zuschüsse an Institute und Bibliotheken wurden gewährt.

Die Stiftungstätigkeit führte Dr. Scrinzi immer wieder in die alte Heimat Südtirol und auch zu bewegenden Begegnungen mit ehemaligen Freiheitskämpfern der Sechzigerjahre.

Im Februar 2003 ehrte der Südtiroler Schützenbund Dr. Scrinzi mit dem Ehrenkranz. In seinen Lebenserinnerungen „Politiker und Arzt in bewegten Zeiten“ schrieb Scrinzi: „Für mich persönlich war diese Auszeichnung eine Art zweiter Einbürgerung in meine Heimat, aus der meine Familie nach vielhundertjähriger Ansässigkeit 1918 ausgebürgert worden war.“

Diese Ehrung hat Dr. Scrinzi mehr gefreut als die vorher erfolgte Verleihung des Großen Goldenen Ehrenzeichens für Verdienste um die Republik Österreich.

In seinem letzten Lebensabschnitt musste Dr. Scrinzi noch erleben, dass die italienischen Behörden die offenbar ungeliebte Stiftungstätigkeit zu kriminalisieren versuchten. Eine Tätigkeit, über die Dr. Scrinzi in seinen Lebenserinnerungen schrieb: „Diese meine Altersarbeit und die Möglichkeit, für meine Landsleute manch Gutes tun zu können, waren Erfüllung für mich, die Wiederbegegnung mit einer seligen Kindheits- und Jugendliebe. Und wären es nur diese Jahre …, dann hätte mein Leben einen Sinn gehabt.“

15:18 Publié dans Actualité, Hommages | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : otto scrinzi, hommages, tyrol, autriche, europe, affaires européennes, europe centrale, mitteleuropa, europe alpine, nécrologie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

di Lorenzo Scala

Fonte: statopotenza