Wertvollzug

Wertvollzugmercredi, 01 juin 2011

Le face à face russo-chinois

Le face à face russo-chinois : le « vide » sibérien face « au trop plein » chinois

par Marc ROUSSET

La Russie coopère avec la Chine dans le cadre de l’Organisation de coopération de Shanghaï (O.C.S.) qui vise à empêcher toute incursion de l’O.T.A.N. (ou des États-Unis seuls) en Asie centrale. Mais parallèlement, Moscou est très préoccupée de la montée en puissance de la Chine avec qui elle partage 4 300 km de frontières communes. La Russie ne peut oublier que les seules invasions du territoire russe qui aient réussi venaient toujours de l’Est. Moscou est donc de facto très ouvert à toute coopération européenne qui lui permet d’accroître l’encadrement international de la puissance chinoise émergente et également de renforcer sa capacité à défendre les richesses et le potentiel économique de la Sibérie, l’enjeu du XXIe siècle entre la Grande Europe de Brest à Vladivostok et la Chine.

J’ai à maintes reprises demandé aux puissances occidentales de ne pas identifier le communisme soviétique à la Russie et l’histoire de la Russie » a pu dire Alexandre Soljenitsyne. La Russie est en fait la sentinelle de l’Europe face à la Chine et à l’Asie centrale. L’Europe doit se considérer comme l’« Hinterland » de la Russie et voir dans la Sibérie le « Far East » de la Grande Europe. L’Europe ne va pas de Washington à Bruxelles, mais de Brest à Vladivostok. En Sibérie, en Asie centrale, l’Européen, c’est le Russe ! Ces thèmes ont été abordés dans mon ouvrage La Nouvelle Europe Paris-Berlin-Moscou. Il est donc intéressant de s’interroger sur ce que certains ont appelé le « péril jaune » pour le monde européen, suite au déséquilibre structurel démographique entre la Chine et la Russie et au « vide sibérien » face au « trop plein » chinois.

La démographie chinoise

La population de la République populaire de Chine s’élevait fin 2010 à 1 341 000 000 d’habitants. Si l’on y rajoute Hong Kong, Macao et Taïwan, la population de la Chine est la plus grande du monde et s’élève à 1 370 000 000 d’habitants, soit plus du cinquième de l’humanité.

La baisse rapide de la mortalité et le retard du contrôle des naissances sous Mao Tsé-Toung, encourageant un temps les Chinois à procréer une armée de « petits soldats » ont contribué à une forte croissance démographique. En 1953, la Chine totalisait seulement 582 000 000 habitants.

Toutefois, selon les dernières projections démographiques de l’O.N.U. (2008), la population chinoise pourrait ne jamais atteindre 1 500 000 d’habitants, plafonnant à 1 460 000 000 en 2035 avant d’amorcer une décroissance. La politique de l’enfant unique pratiquée par la Chine depuis 1979 sur la décision de Deng Xiao-Ping a porté ses fruits : quatre cents millions de naissances auraient été évitées en vingt-cinq ans. Le taux de fécondité a atteint une moyenne de 1,77 enfant par femme entre 2005 et 2010 quand il était de 4,77 entre 1970 et 1975 et déjà de 2,93 enfants par femme en moyenne les cinq années suivantes.

Il faut bien mesurer les limites de la politique de l’enfant unique. Dès sa mise en place, la loi obligeant tous les Chinois mariés à n’avoir qu’un seul enfant a été battue en brèche par deux exceptions de taille : les couples de paysans avaient droit à deux enfants si le premier s’avérait être une fille, et les ethnies non Han n’étaient pas soumises à la loi car menacées puisque minoritaires. D’autre part, seules les zones urbaines et les six provinces relevant du pouvoir central ont été soumises à la loi de l’enfant unique. Cet ensemble constitue 35 % seulement de la population chinoise totale. La totalité de la Chine a donc, en réalité, 1,47 enfant par couple.

En 2002, une loi autorisait un couple à avoir plusieurs enfants moyennant une taxe de six cents euros par enfant supplémentaire. Depuis juillet 2007, le gouvernement central autorise les couples composés de deux enfants uniques à avoir, eux-mêmes, deux enfants. Une ville comme Shanghaï, dont le niveau de vieillissement de la population est l’un des plus élevé du pays, est allée plus loin en 2009. Elle encourage les couples à avoir deux enfants en supprimant notamment les aides sociales allouées jusque là aux couples sans enfants.

Le gouvernement chinois aurait ainsi tendance à assouplir la politique de l’enfant unique. La Chine est tiraillée entre deux maux, surpopulation et déséquilibre entre les sexes, vieillissement de la population provoqué par un faible taux de la natalité. Les plus de 65 ans étaient cent millions en 2008; ils seront trois cent quarante millions en 2050, soit près de 25 % de la population. La réalité compliquée de la question démographique chinoise ne préjuge pas de ce que décidera finalement le gouvernement chinois. Un fait structurel et objectif demeure : il y aura toujours plus d’un milliard de Chinois au Sud de la Sibérie. Le déséquilibre structurel démographique de l’ordre de 1 à 10 avec la Russie est d’autant plus préoccupant que, comme le disait Aristote, « la nature a horreur du vide ».

Évolution et perspectives de la démographie russe

Le début du déclin démographique russe coïncide avec l’arrivée de Gorbatchev au pouvoir (1985 – 1991), c’est-à-dire avec la mise en place de la Perestroïka suivie de l’effondrement du système soviétique. En 1990, la Russie comprenait cent quarante-neuf millions d’habitants, cent quarante-cinq millions d’habitants en 2001 et cent quarante-deux millions en 2007, soit sept millions d’habitants en moins de vingt ans, un rythme de croisière de disparition du peuple russe de 400 000 citoyens de moins chaque année. En fait, le rythme de disparition était d’environ 800 000 habitants par an car, depuis la fin de l’U.R.S.S., 400 000 Russes ont quitté chaque année les ex-républiques soviétiques pour la mère patrie.

Au début des années 2000, selon Boris Revitch du Centre de démographie russe, l’espérance de vie était de 59 ans pour un homme à la naissance, soit vingt ans de moins qu’en Europe occidentale, pour plusieurs raisons : l’alcoolisme (34 500 morts par an), le tabagisme (500 000 morts par an), les maladies cardio-vasculaires (1 300 000 de morts par an), le cancer (300 000 morts par an), le S.I.D.A., les accidents de la route (39 000 morts par an), les meurtres (36 000 morts par an), les suicides (46 000 décès par an), la déficience du système de santé qui faisait la fierté de l’U.R.S.S. et qui était devenue une catastrophe sanitaire avec, par exemple, une mortalité infantile (11 pour 1000), deux fois plus élevée que dans l’U.E.

Tandis que de plus en plus de Russes mouraient, de moins en moins naissaient. À la fin des années 1990, il y avait au minimum trois millions d’I.V.G. par an en Russie, pour un million de naissances, avec un taux de fécondité tombé au plus bas en 1999 à 1,16 enfants par femme. L’habitat trop exigu dans les grands immeubles du système soviétique contribuait à la nouvelle habitude de l’enfant unique.

Dans son discours au Conseil de la Fédération en mai 2006, le président Poutine a confirmé la mise en place d’une politique nataliste par son bras droit Dimitri Medvedev, en aidant les jeunes couples à faire un second, voire un troisième enfant. Une batterie de mesures a été prise pour aider à la natalité. Les plus importantes sont des primes financières de l’État, des avantages fiscaux, mais aussi des aides au crédit et au logement. Les résultats du plan Medvedev couplés avec une politique migratoire de Russes de l’ex-U.R.S.S. et de nombreux Ukrainiens ont été fulgurants. La population a décru de 760 000 habitants en 2005, 520 000 habitants en 2006, 238 000 en 2007, 116 000 en 2008. En 2009 avec 1 760 000 naissances, 1 950 000 décès, 100 000 émigrants et 330 000 naturalisations, la population russe a augmenté pour la première fois depuis quinze ans de quelque 50 000 habitants. Le taux de fécondité de 1,9 enfant par femme en 1990, tombé à 1,1 enfant par femme en 2000 était remonté à 1,56 enfants par femme en 2009, soit un taux similaire à celui de l’Union européenne de 1,57 enfants par femme. Bien que le nombre d’avortements ait diminué, on recensait encore en 2008 1 234 000 avortements pour 1 714 000 naissances.

D’ici à 2050, la démographie russe va donc être soumise à deux forces contradictoires : d’une part, la politique nataliste gouvernementale, l’opinion publique hostile à l’immigration non russe, la construction en plein essor, les améliorations en matière d’éducation, d’agriculture et de santé (les quatre « projets nationaux »), le retour aux valeurs traditionnelles, à la religion orthodoxe et d’autre part l’effet d’hystérésis, suite à la chute de l’U.R.S.S., qui correspond à un rétrécissement structurel de la strate de population en âge de procréer (1), les influences néfastes de l’Occident et de sa « culture de mort » (libéralisation de la contraception, de l’avortement, de l’homosexualité, féminisme et travail des femmes, regroupement des populations dans les métropoles, destruction des petits agriculteurs, allocations familiales attribuées de plus en plus aux populations immigrées)

Trois prévisions démographiques majeures ont été envisagées pour l’année 2030 en 2010 par le Ministère russe de la Santé.

Selon une prévision estimée mauvaise, la population devrait continuer à baisser pour atteindre 139 630 000 en 2016 et 128 000 000 d’habitants en 2030. Le taux d’immigration resterait « faible » autour de 200 000 par an pour les vingt prochaines années.

Selon une prévision estimée moyenne, la population devrait atteindre 139 372 000 habitants en 2030. Le taux d’immigration serait contenu à 350 000 nouveaux entrants par an.

Selon une prévision haute, la population devrait augmenter à près de 144 000 000 habitants en 2016 et continuer à augmenter jusqu’à 148 000 000 en 2030. Le taux d’immigration serait plus élevé dans cette variante, soutenant la hausse de la population et avoisinerait les 475 000 nouveaux entrants par an. Sur vingt ans, on arriverait à une « immigration » équivalente à 8 % de la population du pays. Celle-ci serait principalement du Caucase et de la C.E.I., soit des populations post-soviétiques, russophones dont des communautés sont déjà présentes en Russie, et donc pas foncièrement déstabilisantes.

Pour l’année 2050, il nous paraît bien difficile pour ne pas dire impossible de se prononcer. Il semble donc plus raisonnable de retenir pour l’année 2050 dans les prévisions 2006 de l’O.N.U. (2), le point haut de 130 millions d’habitants, la prévision de l’O.N.U. étant de 107 800 000 habitants avec un point bas de 88 000 000 habitants.

L’enjeu de la Sibérie

Sibérie tient son nom de la petite ville de Sibir. L’étymologie du mot est incertaine, mais le terme pourrait provenir du turco-mongol sibir désignant un peuplement très dispersé. La Sibérie est la partie asiatique de la Fédération de Russie : une immense région d’une surface de 13 100 000 km2 (environ vingt-quatre fois la surface de la France) très peu peuplée (39 000 000 habitants soit environ 3 habitants au km2). Cette partie Nord de l’Asie représente 77 % de la surface de la Russie, elle-même deux fois plus grande que les États-Unis, mais seulement 27 % de sa population.

La Sibérie a les plus grandes forêts de la planète. L’intérêt économique majeur réside dans les richesses de son sous-sol, de pétrole et de gaz qui pourraient aller jusqu’au pôle Nord où la Russie a planté son drapeau par plus de 4 000 m de fond en juillet 2007. La Sibérie fournit de l’hydro-électricité et du charbon avec de riches bassins tels que celui du Kouzbass. Grâce à la Sibérie, avec cinq cents années de réserve, la Russie est le deuxième producteur mondial de charbon derrière les États-Unis. La Sibérie possède des gisements d’argent, d’or, d’uranium, de cuivre, de titane, de plomb, de zinc, d’étain, de manganèse, de bauxite, molybdène, de nickel… Un diamant sur quatre extrait dans le monde provient de Sibérie. Le réchauffement climatique ouvre la perspective d’exploitation d’autres immenses ressources en hydrocarbures. Moscou va être un acteur de premier plan dans la pièce qui va se jouer pour les ressources naturelles, la science et le transit maritime du XXIe siècle dans le Grand Nord.

La Sibérie d’aujourd’hui : un avant-poste des Européens face à la Chine

La Moscovie s’est construite contre les vagues déferlantes tartares et s’est toujours représentée comme une forteresse érigée au cœur d’un océan de plaines immenses et sans bornes. Les Russes ont colonisé la Sibérie, le Caucase et l’Asie centrale parce qu’ils étaient obligés de le faire. La Russie a connu pendant deux siècles le joug tartaro-mongol. La colonisation russe correspondait à des impératifs vitaux pour sa survie, à l’obligation géopolitique de trouver des frontières naturelles dont elle était dépourvue et qui était indispensable à sa protection. L’expansionnisme russe, contrairement à celui de l’Europe occidentale, était défensif et structurel.

Si les savants ont déclaré solennellement le paisible Oural au paysage ondulé, dont la pente ne devient raide que dans le nord, loin de la toundra, comme une ligne de démarcation entre l’Asie et l’Europe, les autochtones, eux, le considèrent comme une ligne de partage des eaux couverte de forêt, et rien de plus.

Les Russes se souviennent de Yermak comme d’un aventurier cosaque aussi remarquable que Magellan, d’un conquistador aussi intrépide que Cortez, car ce fut Yermak qui conduisit la première mission réussie dans la mystérieuse Sibérie, et qui inspira aux Russes l’idée de repousser leurs frontières de 6 200 km plus à l’Est, jusqu’à la côte asiatique du Pacifique. Trois fois dans l’histoire, la Sibérie fut traversée par des conquérants : par les hordes de cavaliers d’Attila et de Gengis Khan puis, en sens inverse, par le millier d’hommes de Yermak. C’est en 1558 qu’Ivan IV le Terrible accorde des privilèges d’exploitation des territoires situés à l’Est de l’Oural aux Stroganov, équivalents des Fugger, à la recherche de fourrures. Un mouvement est lancé qui conduira les cosaques sur les rives du Pacifique en 1639 (et même plus tard en Alaska). Tandis que Français et Allemands se disputaient quelques lambeaux de territoire en Italie et aux Pays-Bas, une poignée de cavaliers navigateurs explorateurs parcourait une étendue vaste comme vingt fois la France ou l’Allemagne, plusieurs centaines de fois l’Alsace, la Flandre ou le Milanais. À la fin du XVIIIe siècle, la Russie a conquis la Sibérie. Ce territoire reste aujourd’hui vide même si l’une des principales retombées du Transsibérien fut l’augmentation substantielle de la migration vers l’Est de l’Empire russe. 3 800 000 personnes émigrèrent vers la Sibérie entre 1861 et 1914 et contribuèrent à la russification des populations indigènes de Sibérie. Sans le Transsibérien, ces populations auraient émigré vers l’Amérique. La Sibérie ne comptait que 1 500 000 habitants en 1815, dix millions en 1914 et vingt-trois millions en 1960.

La nécessité de l’espace : une vérité qui n’est plus reconnue

Que depuis toujours la politique soit une lutte pour l’espace, pour acquérir une base, une place, que l’espace constitue l’alpha et l’oméga de toute vie, que la politique, la science, le commerce ne sont rien d’autre que l’acquisition de cet espace, voilà une vérité qui n’est plus reconnue.

Un avantage évident revient à qui, outre sa technicité, dispose aussi des matières premières nécessaires. Qui n’a que sa technique à offrir et doit importer les matières premières est désavantagé. C’est l’indépendance à long terme que de pouvoir se nourrir des produits de sa terre, que d’exploiter ses propres matières premières indispensables à la vie et à la protection, que de pouvoir se défendre avec des armes conçues et fabriquées chez soi. La certitude de pareils avantages, c’est un espace suffisamment grand qui la confère, si l’on s’en tient à l’exemple américain. A contrario, le Japon redeviendra à terme le vassal de la Chine simplement en raison du manque d’espace et donc de sa plus faible population par rapport à son futur suzerain.

L’espace contient tout ce dont nous avons besoin, même l’air que nous respirons et l’eau qui nous désaltère. Il constitue donc le bien suprême. Plus d’espace, c’est plus d’oxygène, plus de pain, plus de rivières et de forêts, plus de terrain pour bâtir sa maison, plus de terre pour les jardins, plus de possibilités de repos, plus de distance d’homme à homme, une sphère privée élargie pour chacun, plus d’occasions de fuir les bruits et l’intoxication des villes, plus de calme pour penser, élaborer des projets, travailler, rêver, réfléchir. C’est accroître tout ce qui rend la vie digne d’être vécue et qui, hélas, se fait de plus en plus rare. Renoncer à l’espace, c’est renoncer à la vie.

L’Eurasie, du Pacifique à la Baltique, peut contenir plus d’hommes que le territoire de l’Europe occidentale. Un droit à l’occupation doit donc être reconnu aux peuples européens sur l’espace allant du Sud du Portugal au détroit de Behring, en incluant le Nord-Caucase et la totalité de l’espace sibérien. Sur cet espace, cinq cents millions d’Européens et cent cinquante millions de Russes devraient pouvoir prolonger jusqu’à Vladivostok les frontières humaines et culturelles de l’Europe. Le grand défi de la Sibérie est son trop faible peuplement par trente-neuf millions de Russes avec le risque d’une colonisation rampante par la Chine. La Sibérie restera-t-elle russe et donc sous le contrôle civilisationnel européen ou deviendra-t-elle chinoise et asiatique ?

Les traités inégaux et l’actuelle frontière entre la Chine et la Russie

En 1689, suite à cinquante ans de confrontations armées inégales numériquement entre les cosaques et les Mandchous, les empires chinois et russe signent le traité de Nertchinsk : la Russie renonce à l’intégralité du bassin de l’Amour. L’empire Qing n’avait jamais occupé ces terres du nord, mais il ne souhaitait pas voir les Russes s’y installer. À partir du XVIIIe siècle, la Russie cherche cependant à devenir une puissance navale dans l’océan Pacifique; elle encouragea les Russes à venir s’y établir et développe une présence militaire dans la région. La Chine n’avait jamais gouverné réellement la région et les avancées russes passèrent inaperçues. Les habitants de ces territoires n’étaient pour la plupart pas des Hans, mais des Mandchous, des Tibétains ou des Turcs. Au milieu du XIXe siècle, le bassin de l’Amour restait ainsi une terre sauvage où sur un million de km2 ne vivaient pas plus de trente mille personnes.

Mais dans les années 1850, la donne géopolitique a changé, l’Empire chinois est affaibli. En 1842, la Chine, suite à la Guerre de l’Opium, avait cédé Hong Kong par le traité de Nankin. Une nouvelle expédition russe a lieu pour explorer la région du fleuve Amour. En 1858, la Chine doit signer le traité d’Aïgoun, considéré comme un des nombreux traités inégaux avec les puissances occidentales. La Russie prend le contrôle de la rive gauche de l’Amour, de l’Argoun à la mer. « La Russie a réussi à arracher à la Chine un territoire grand comme la France et l’Allemagne réunis et un fleuve long comme le Danube », commentait Engels dans un article. Deux ans plus tard, en même temps que le sac du Palais d’Été par la coalition franco-anglaise, la Russie confirme et amplifie ses gains par la convention de Pékin. Elle obtient la cession de la région de Vladivostok et Khabarovsk sur les rives droites de l’Amour et de l’Oussouri. Vladivostok qui était un village chinois du nom de Haichengwei « Baie des concombres de la mer » est fondée officiellement en 1860 et signifie « Seigneur de l’Orient ».

La Russie cherche plus tard à contrôler la Mandchourie pour protéger la Sibérie et élargir son ouverture sur l’océan Pacifique. Elle obtient la cession de Port-Arthur (Lüshunkou en chinois). La défaite face au Japon en 1905 ruine cette politique. La Russie renonce à la Mandchourie et doit céder Port-Arthur. Ce dernier retrouvera temporairement la souveraineté soviétique entre 1945 et 1955.

Dans les années 1960, les relations entre la Chine et l’U.R.S.S. se dégradent fortement et MaoTsé-Toung remet en cause les traités signés au XIXe siècle entre les empires russe et mandchou. À partir de 1963, les incidents frontaliers se multiplient. Dès 1964, le président Mao, dans un discours aux parlementaires japonais, fait allusion aux territoires perdus. Ces tensions aboutissent en 1969 à un affrontement armé pour le contrôle de l’île Damanski sur la rivière Oussouri qui fait des centaines de morts, en majorité chinois, mais n’aboutit pas à un nouveau tracé. L’U.R.S.S. envisage même de détruire préventivement les installations nucléaires chinoises. Dans les années qui suivent, la situation reste très tendue et n’évolue guère jusqu’aux années 1980.

À partir de 1988, à l’instigation de Mikhaïl Gorbatchev, les relations entre l’U.R.S.S. et la Chine se détendent et les négociations reprennent. Le 16 mai 1991, la Russie et la Chine signent un traité sur les frontières, qui laisse toutefois en suspens le sort de certains petits territoires disputés. Ces derniers points sont réglés par différents accords signés dans un contexte diplomatique nettement plus détendu. Le dernier traité est signé en 2004. À l’issue de ces règlements, la Chine a réalisé quelques gains territoriaux très mineurs par rapport aux traités antérieurs.

Le résultat final, c’est qu’aujourd’hui la frontière sino-russe est constituée de deux morceaux de longueurs très inégales situés de part et d’autre de la Mongolie. Elle est définie dans son intégralité depuis 2004. Le tronçon de l’Ouest ne mesure que 50 km. Le tronçon de l’Est mesure 4 195 km. C’est la sixième plus longue frontière internationale du monde. L’intégration des territoires frontaliers par les deux empires russe et chinois a été tout à fait différente. Les plaines du Nord-Est de la Chine ont été rapidement peuplées et mises en valeur par des colons chinois dès le début du XIXe siècle. Par contre, le peuplement de l’Extrême-Orient russe par des colons venus de Russie d’Europe a été moins important et beaucoup plus long (3). La différence entre les deux peuplements a donné naissance à une ligne de discontinuité de part et d’autre du fleuve Amour et de la rivière Oussouri : d’un côté, sept millions de Russes, de l’autre, plus de soixante millions de Chinois vivant dans les provinces frontalières du Jilin et du Heilongjiang. Les manuels d’histoire chinois apprennent aux écoliers que l’Extrême- Orient russe a été pris par la force à La Chine qui a signé les traités sous la menace.

Le danger chinois démographique et économique à court terme en Extrême-Orient et en Sibérie russe

En Russie, l’opinion publique est hostile à l’immigration. Contrairement aux affabulations de l’Occident, même si le « péril jaune » est très réel à terme, plus particulièrement en Sibérie et en Extrême-Orient, il y a à ce jour en Russie, un maximum de 400 000 Chinois, selon Zhanna Zayonchkouskaya, chef de Laboratoire de migration des populations de l’Institut national de prévision économique de l’Académie des Sciences de Russie, et non pas plusieurs millions comme cela a pu être annoncé. Les Russes ont veillé au grain et ont pris des mesures très sévères pour éviter une possible invasion. La seule immigration qui a été favorisée est le rapatriement de Russes établis dans les anciennes républiques soviétiques (Kirghizistan, Kazakhstan, Pays baltes, Turkménistan. ). Des villes comme Vladivostok, Irkoutsk, Khabarovsk, Irkoutsk Krasnoïarsk… et même Blagovetchensk, à la frontière chinoise, sont des villes européennes avec seulement quelques commerçants ou immigrés chinois en nombre très limité. Une invasion aurait pu avoir lieu en Extrême-Orient dans les années 1990, tant la situation s’était dégradée. Il est à remarquer que les migrants chinois de l’époque ont profité du laxisme et de l’anarchie ambiante pour filer à l’Ouest de la Russie. Être clandestin n’est pas aisé aujourd’hui en Extrême-Orient et en Sibérie : la frontière est relativement imperméable; le risque est grand; les hôtels sont sous contrôle étroit; le chaos qui suivit l’éclatement de l’U.R.S.S. est déjà loin.

Il n’en reste pas moins vrai qu’un climat d’hostilité, voire de peur, s’est développé envers les Chinois chez les Russes d’Extrême-Orient qui a été largement utilisé dans le débat russe sur les orientations de politique étrangère (3). En 2001, le XVe congrès du Parti communiste chinois avait décidé d’une stratégie de consolidation de la présence chinoise à l’étranger, en encourageant la population à émigrer. Pékin avait fait savoir à Moscou qu’il n’appuierait sa candidature à l’O.M.C. que contre la promesse de ne pas réglementer l’entrée de la main-d’œuvre chinoise sur le marché du travail russe. Le ministre russe de la Défense, Pavel Grachev, avait pu déclarer : « Les Chinois sont en train de conquérir pacifiquement les confins orientaux de la Russie ». Et, selon un haut responsable russe des questions d’immigration, « nous devons résister à l’expansionnisme chinois ». Le problème est d’autant plus grave, au-delà du taux de la natalité, que la région se vide et que de nombreux Russes repartent en Russie de l’Ouest. Ces dernières années, la région de Magadan a été délaissée par 57 % de sa population, la péninsule du Kamtchaka par 20 % et l’île Sakhaline par 18 %. La densité moyenne en Extrême-Orient est de 1,2 habitant au kilomètre carré contre une moyenne nationale de 8,5. Bref, selon les prévisions les plus pessimistes, l’Extrême-Orient russe peuplé de 6 460 000 personnes au 1er janvier 2010 pourrait ne compter que 4 500 000 habitants en 2015, contre 7 580 000 au plus haut.

Sur le plan économique, en 2002, selon l’analyste Andreï PIontkovsky, 10 % seulement des échanges de l’Extrême-Orient russe se faisaient avec les autres régions de Russie. 90 % des achats extra-provinciaux venaient de Chine, Corée du sud ou Japon à cause du coût prohibitif du fret aérien ou ferroviaire avec l’Ouest de la Russie. À Vladivostok, Khabarovsk, et à Irkoutsk en Sibérie, la plupart des voitures avaient le volant à droite parce qu’elles venaient directement du Japon où l’on conduit à gauche. Des mesures ont été prises tout récemment par les autorités, non sans difficultés, pour favoriser l’achat de voitures russes et abaisser le coût du fret.

La structure des échanges commerciaux bilatéraux avec la Chine s’est renversée depuis la fin de la guerre froide. La Russie devient le « junior partner » de la Chine. Dans les exportations russes vers la Chine, les matières premières dominent : produits minéraux (56,4 %) en 2008, principalement pétrole et dérivés; bois et dérivés (15,5 %); produits de la chimie (13,9 %); métaux et dérivés (5,3 %); seulement 4,4 % pour les machines, l’équipement et les moyens de transport. Les exportations chinoises vers la Russie sont, pour l’essentiel, constituées de ces derniers articles(53,9 %), ainsi que de métaux(8,4 %), de produits chimiques (6,8 %) et de textiles (15,1 %). Les autorités russes ne se satisfont visiblement pas de cet état de fait. Le Kremlin n’accepte pas que la Russie devienne un réservoir de matières premières pour la Chine et insiste constamment sur la nécessité de corriger la structure des exportations russes.

La Russie s’efforce aussi d’orienter les investissements chinois de façon à endiguer la désindustrialisation de l’Extrême-Orient russe. Plus globalement, le Kremlin est convaincu que fermer l’Extrême-Orient et la Sibérie à la Chine et à d’autres partenaires étrangers (Corée, Japon, pays d’Asie du Sud-Est ) reviendrait à les condamner à terme, voire à les perdre en les rendant plus vulnérables aux appétits territoriaux d’autres pays de la région, la Chine en premier lieu. En revanche, mettre en concurrence plusieurs pays étrangers dans cette région permet d’espérer qu’aucun d’entre eux « ne parviendra à atteindre l’hégémonie »; de plus, si les relations avec la Chine devaient se détériorer, la Russie aurait acquis la possibilité de défendre plus efficacement ses zones frontalières puisqu’elle les aura mieux développées. Moscou, on le voit, n’écarte pas complètement la perspective d’une réouverture des problèmes territoriaux avec la Chine, malgré le règlement du litige frontalier en 2008 et l’engagement des deux pays, dans leur traité d’amitié et de bon voisinage, à s’abstenir de toute revendication territoriale mutuelle.

Ce souci russe en Asie orientale apparaît encore plus nettement en Asie centrale. Dans cette région, Moscou ne se sent plus aussi sûr que par le passé de la force de ses moyens d’influence (minorités russes, liens historiques et économiques…). La Chine a considérablement étoffé sa présence économique dans cette zone depuis le début des années 2000 et semble en passe de supplanter la Russie comme premier partenaire commercial des États centre-asiatiques. Face à la force de frappe financière et économique de la Chine, la Russie va-t-elle longtemps pouvoir faire le poids ? Au sein de l’O.C.S., à l’heure de la crise économique globale, c’est Pékin qui a occupé le terrain en consentant aux membres de l’Organisation des prêts d’un montant de dix milliards de dollars. La situation est encore plus grave, aux yeux de Moscou, dans le domaine énergétique : la politique de Pékin va directement à l’encontre de la stratégie du Kremlin, déterminé à contrôler le plus possible les hydrocarbures de la zone Caspienne/Asie centrale afin de conforter ses positions face aux clients européens. Le lancement, fin 2009, du gazoduc Turkménistan – Ouzbékistan – Kazakhstan – Chine qui s’ajoute à l’oléoduc kazakho-chinois ne réjouit pas plus la Russie que les tubes Caspienne – Turquie contournant son territoire promus dans les années 1990 par les États-Unis. Au point que certains experts russes estiment que Moscou pourrait être tenté de fomenter des troubles dans le Turkestan oriental pour faire dérailler les accords énergétiques Chine – Asie centrale.

Les visées chinoises inéluctables à moyen terme sur la Mongolie extérieure et à très long terme sur la Sibérie

Le temps n’est plus où la Russie débordait de forces vives, jusqu’à pouvoir sacrifier vingt millions d’hommes dans la lutte contre le nazisme. On comprend mieux pourquoi les responsables russes continuent de refuser pour le moment de vendre certains matériels de portée stratégique tels que les chasseurs bombardiers de type TU 22 ou TU 95, ou encore des sous-marins de quatrième génération de la classe « Amour » ou « Koursk ». Selon le chancelier Bismarck, « l’important, ce n’est pas l’intention, mais le potentiel » et comme chacun sait, l’histoire n’est pas irréaliste (Irrealpolitik) et droit-de-l’hommiste, mais réaliste (Realpolitik) et imprévisible.

La montée en puissance de la Chine ne se traduira pas seulement par le remplacement progressif de l’anglo-américain par le mandarin en Asie, mais aussi par des visées territoriales.

L’expansionnisme nationaliste chinois se traduit d’une façon forte et brutale pour mater dans l’œuf et empêcher toute velléité de résistance, aussi bien au Tibet qu’au Xinjiang. Le chemin de fer à 6 200 000 dollars qui relie Pékin à Lhassa renforce l’emprise de la Chine sur le Tibet et sa capacité de déploiement militaire rapide contre l’Inde. Il est probable qu’après avoir maintenant récupéré Hong Kong et Macao de façon pacifique et selon les traités, la Chine a déjà et aura comme première préoccupation de rétablir sa souveraineté sur l’île de Taïwan. Avec ses 1 400 missiles pointés vers « l’île rebelle », Pékin a menacé d’écraser sous le feu ses « frères » taïwanais, s’ils devaient proclamer leur indépendance. Dans les faits, la réunification avec Taïwan est bel et bien en marche. Le mandarin est la langue officielle à Taïwan. Les vols aériens et les communications ont été progressivement rétablis avec le continent. La symbiose est de plus en plus étroite entre les deux économies

Une fois Taïwan sous sa coupe, la Chine cherchera tout naturellement à récupérer la Mongolie extérieure cédée par la Chine à la Russie en 1912 et devenue ensuite une république populaire, puis un État indépendant lors du démantèlement de l’U.R.S.S. « La Chine va d’abord s’occuper de Taïwan, puis ce sera notre tour » a pu dire B. Boldsaikhan, chef politique en Mongolie extérieure du mouvement Dayar Mongol. État de 1 535 000 km2, sous-peuplée avec seulement 2 800 000 habitants, dotée de très riches gisements aurifères et d’uranium, la Mongolie extérieure, pendant de la Mongolie intérieure autonome chinoise, est déjà contrôlée économiquement par les Chinois, quelque 100 000 Russes ayant fait très rapidement leurs valises en 1990. La Mongolie extérieure sera un jour inéluctablement envahie comme le Tibet et, au-delà de quelques protestations américaines, la Chine rétablira en fait une souveraineté légitime historique sur l’ensemble de la Mongolie qui date de la soumission de la Mongolie aux Mandchous en 1635. Gengis Khan est considéré en Chine comme un héros de la nation chinoise; un mausolée lui a été construit à Ejin Horo, dans la province chinoise de Mongolie intérieure, pour le huit centième anniversaire de sa naissance.

Puis ce sera le tour de l’Extrême-Orient russe. Selon Andreï Piontkovsky, directeur du Centre d’études stratégiques de Moscou, c’est la Chine de l’Orient et non pas l’Occident qui représente la menace stratégique la plus sérieuse pour la Russie. Ces revendications s’inscrivent dans le droit fil du concept stratégique « d’espace vital » d’une grande puissance qui, selon les théoriciens chinois, s’étend bien au-delà de ses frontières.

La Russie et la Chine occupent ensemble un espace géographiquement continu entre la mer Baltique et la Mer de Chine de 26 600 000 km2, habités par 1 400 000 000 personnes. Des similitudes apparaissent lors de l’analyse de l’histoire de ces deux grands et complexes blocs géopolitiques. Tous deux s’étaient constitués au détriment de l’empire nomade des Mongols, dont la Mongolie enclavée entre la Chine et la Russie, constitue le dernier vestige, avec la Mongolie intérieure, rattachée à la Chine, et la Bouriatie faisant partie de la Russie. Tous deux possèdent une zone périphérique, peu peuplée et sous-exploitée (la Sibérie et l’Extrême-Orient pour la Russie, le Tibet et le Xinjiang pour la Chine). Cependant, la Chine est plus peuplée que la Russie. Son poids démographique constitue en même temps un atout (le marché le plus grand de la planète) et un handicap majeur (le pays est surpeuplé et proche de la saturation). Certains spécialistes estiment que le seuil de l’auto-suffisance chinoise se trouve à 1 500 000 000 habitants. En Sibérie et en Extrême-Orient, il y a tout ce qui manque à la Chine : les hydrocarbures, les matières premières et l’espace pour développer l’agriculture. Un paradoxe se dessine, car la Russie est un géant géographique et la Chine manque d’espace. Ces deux ensembles géopolitiques sont donc condamnés soit à collaborer, soit à s’affronter. On se rappellera que le projet communiste a réuni ces deux géants géopolitiques pendant onze ans. La perspective d’un tel rapprochement était devenue le pire des cauchemars pour les responsables occidentaux et américains.

Le retour de la Russie sur le Pacifique était logique et inévitable. Cependant, avec un déclin démographique, la Russie est-elle capable de mettre seule en valeur la Sibérie ? Il n’est pas suffisant d’avoir une volonté politique, il faut également disposer de moyens. C’est pourquoi l’affrontement paraît à long terme inéluctable. Il est clair que l’O.C.S. n’est qu’une parenthèse tactique pour les deux futurs adversaires afin de mieux pouvoir contrer l’Amérique en Asie centrale. La puissance balistique de la Russie avec ses 2 200 têtes nucléaires est dans un horizon prévisible la seule garantie de non invasion de la Sibérie par la Chine.

Une leçon à méditer…

Selon Hélène Carrère d’Encausse, la Sibérie est « un espace vide aux abords d’une Chine surpeuplée » (4). Si l’Europe se considère à terme comme l’Hinterland de la Russie et ne se laisse pas envahir par l’immigration extra-européenne en préservant sa civilisation, elle peut constituer avec la Russie la Grande Europe qui serait une forteresse inexpugnable face à la Chine, l’Islam et l’Asie centrale. Dans ce cas, la Sibérie pourrait rester sous contrôle civilisationnel russe et donc européen.

Le schéma alternatif, c’est que les cent quarante millions descendants des Scythes soient envahis par un milliard et demi de Chinois qui brûlent de passer l’Amour tandis que l’Europe, déversoir naturel de l’Afrique, comme l’a d’ailleurs explicité le Libyen Kadhafi, est tout aussi menacée !

Pour ceux qui trouveront ces propos bien pessimistes, je souhaiterais leur rappeler cette magnifique exposition du musée Guimet : « Kazakhstan : Hommes, bêtes et dieux de la steppe ». Il fut un temps, dès le deuxième millénaire avant notre ère, où le Kazakhstan et l’Ouzbékistan étaient le domaine non des Asiates, mais des Aryens : les Scythes. D’origine et de langue indo-européennes, décrits par Aristote citant Hérodote comme ayant des « cheveux blonds et blanchâtres », les Scythes nomadisaient de l’Ukraine à l’Altaï. Leur civilisation était très riche et d’une rare finesse (art funéraire, maîtrise des métaux précieux, travail des objets utilitaires…). Comment une civilisation aussi brillante dont les chefs entreprenants et guerriers ne craignaient rien tant que mourir dans leur lit, ont-ils disparu ? Sans doute ont-ils été victimes de ce que les Slaves appellent « la peste blanche », la dénatalité. Et son inéluctable corollaire, la submersion par des ethnies à la natalité galopante et l’inévitable métissage. Dans leur match démographique contre la déferlante asiatique, les Scythes ne pesèrent pas lourd. Les hordes tartares les avalèrent et le génie de la race se tarit.

Une leçon à méditer pour les Européens de l’Ouest face à l’Afrique et pour les Russes en Sibérie face au trop plein chinois.

Marc Rousset

Notes

1 : Hélène Carrère d’Encausse, La Russie entre deux mondes, Fayard, 2009, p. 65.

2 : cf. le rapport de l’O.N.U., World Population Prospects : the 2006 revision.

3 : Sébastien Colin, « Le développement des relations frontalières entre la Chine et la Russie », dans les Études du C.E.R.I., n° 96, juillet 2003.

4 : Hélène Carrère d’Encausse, op. cit., p. 172.

Article printed from Europe Maxima: http://www.europemaxima.com

URL to article: http://www.europemaxima.com/?p=1982

00:20 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes, Géopolitique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : chine, russie, sibérie, politique internationale, affaires asiatiques, affaires européennes, europe, asie, géopolitique |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 31 mai 2011

Peter Scholl Latour: révolutions arabes et élimination de Ben Laden

Révolutions arabes et élimination de Ben Laden

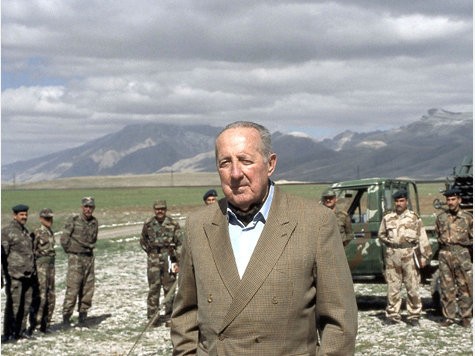

Entretien avec Peter Scholl-Latour

Propos recueillis par Bernhard Tomaschitz

Q. : Professeur Scholl-Latour, vous revenez tout juste d’un voyage en Algérie. Quelle est la situation aujourd’hui en Algérie ? Une révolution menace-t-elle aussi ce pays ?

PSL : La situation en Algérie est plutôt calme et j’ai même pu circuler dans les campagnes, ce qui n’est pas sans risques, mais notre colonne a bien rempli sa mission. Vers l’Ouest, j’ai pu circuler tout à fait librement mais en direction de l’Est, de la Kabylie, je suis arrivé seulement dans le chef-lieu, Tizi Ouzou ; ailleurs, la région était bouclée. Pas tant en raison d’actes terroristes éventuels —ceux-ci surviennent mais ils sont assez rares— mais parce que des enlèvements demeurent toujours possibles et les autorités algériennes les craignent.

Q. : Au contraire de l’Algérie, la Libye ne retrouve pas le calme, bien au contraire. Tout semble indiquer que la situation de guerre civile conduit au blocage total. Comment jugez-vous la situation ?

PSL : Je pense qu’à terme Kadhafi et son régime vont devoir abandonner la partie ou que le Colonel sera tué. Mais ce changement de régime et cette élimination du chef n’arrangeront rien, bien évidemment, car, en fin de compte, les deux régions qui composent la Libye, la Tripolitaine et la Cyrénaïque sont trop différentes l’une de l’autre, sont devenues trop antagonistes, si bien que nous nous trouverons toujours face à une situation de guerre civile. Surtout que le pays n’a jamais connu de système politique démocratique. Cela n’a jamais été le cas ni dans la phase brève de la monarchie ni auparavant sous la férule italienne : finalement, il n’y a pas de partis constitués en Libye ni de personnalités marquantes qui pourraient s’imposer au pays tout entier. On peut dire que le système ressemble, mutatis mutandis, à ceux qui régnaient en Tunisie et en Egypte.

Q. : Donc ce qui menace la Libye, c’est un scénario à l’irakienne…

PSL : Cela pourrait même être pire. Nous pourrions déboucher sur un scénario à la yéménite (BT : faibles structures étatiques et conflits intérieurs) ou, plus grave encore, à la somalienne (BT : effondrement total de toutes les structures étatiques et domination de groupes islamistes informels). La réaction générale des Algériens est intéressante à observer : je rappelle que, dans ce pays, les militaires avaient saisi le pouvoir en 1991, parce que le FIS islamiste, à l’époque encore parfaitement pacifique, avaient gagné les élections libres et emporté la majorité des sièges ; à la suite du putsch militaire, les Algériens ont connu une guerre civile qui a fait 150.000 morts. Aujourd’hui, l’homme de la rue en Algérie dit qu’il en a assez des violences et des désordres. Les Algériens observent avec beaucoup d’inquiétude les événements de Libye et se disent : « Si tels sont les effets d’un mouvement démocratique, alors que Dieu nous en préserve ! ».

Q. : Quel jugement portez-vous en fait sur les frappes aériennes de l’OTAN contre Kadhafi, alors que la résolution n°1973 de l’ONU n’autorise que la protection des civils ? Il semble que l’OTAN veut imposer de force un changement de régime…

PSL : Bien entendu, l’OTAN a pour objectif un changement de régime en Libye. Le but est clairement affiché : l’OTAN veut que Kadhafi s’en aille, y compris sa famille, surtout son fils Saïf al-Islam et tout le clan qui a dirigé le pays pendant quarante ans. Pourra-t-on renverser le régime de Kadhafi en se bornant seulement à des frappes aériennes ? Ce n’est pas sûr, car les insurgés sont si mal organisés et armés qu’ils essuient plus de pertes par le feu ami que par la mitraille de leurs ennemis.

Q. : Comment peut-on jauger la force des partisans de Kadhafi ?

PSL : A Tripoli, c’est certain, les forces qui soutiennent Kadhafi sont plus fortes qu’on ne l’avait imaginé. Certaines tribus se sont rangées à ses côtés, de même qu’une partie de la population. Car, en fin de compte, tout allait bien pour les Libyens : ils avaient le plus haut niveau de vie de tout le continent africain. Certes, ils étaient complètement sous tutelle, sans libertés citoyennes, mais uniquement sur le plan politique. Sur le plan économique, en revanche, tout allait bien pour eux. Kadhafi dispose donc de bons soutiens au sein de la population, ce que l’on voit maintenant dans les combats qui se déroulent entre factions rivales sur le territoire libyen. De plus, dans les pays de l’aire sahélienne, il a recruté des soldats qu’il paie bien et qui combattent dans les rangs de son armée.

* * *

Q. : Après la mort d’Ousama Ben Laden, le terrorisme islamiste connaîtra-t-il un ressac ? Al-Qaeda est-il désormais un mouvement sans direction ?

Q. : Après la mort d’Ousama Ben Laden, le terrorisme islamiste connaîtra-t-il un ressac ? Al-Qaeda est-il désormais un mouvement sans direction ?

PSL : Au cours de ces dernières années, Ousama Ben Laden n’a plus joué aucun rôle et je ne sais pas s’il a jamais joué un rôle… Ben Laden était un croquemitaine, complètement fabriqué par les Américains. Ousama Ben Laden n’a donc jamais eu l’importance qu’on lui a attribuée. Le rôle réel de Ben Laden relève d’un passé bien révolu : il a été une figure de la guerre contre l’Union Soviétique, qui, dans le monde arabe, en Arabie Saoudite, en Iran et ailleurs, a coopéré avec les Américains et les services secrets pakistanais pour récolter de l’argent et des armes afin d’organiser la résistance afghane contre les Soviétiques. Dès que ceux-ci ont été vaincus, il s’est probablement retourné contre les Américains mais il n’a certainement pas organisé les prémisses de l’attentat contre le World Trade Center.

Q. : Et qu’en est-il d’Al-Qaeda, qui, selon toute vraisemblance, semble agir depuis l’Afghanistan ?

PSL : Les combattants d’Al-Qaeda, qui ont été actifs sur la scène afghane, ne sont pas ceux qui se sont attaqués au World Trade Center. Les auteurs de cet attentat étaient des étudiants, dont une parte est venue d’Allemagne et qui étaient de nationalité saoudienne. Ensuite, il faut savoir que le mouvement al-Qaeda n’est nullement centralisé et, de ce fait, centré autour de la personnalité d’un chef, comme on aime à le faire croire. La nébuleuse Al-Qaeda est constituée d’une myriade de petits groupuscules et c’est la raison majeure pour laquelle je ne crois pas qu’elle cessera d’agir à court ou moyen terme.

Q. : Les Etats-Unis veulent étendre à la planète entière la « démocratie » et l’Etat de droit, mais voilà que Ben Laden est abattu sans jugement par un commando d’élite. Cette action spectaculaire aura-t-elle des effets sur la crédibilité des Etats-Unis au Proche et au Moyen Orient, surtout sur les mouvements de démocratisation ?

PSL : Cela n’aura absolument aucun effet. Car les Etats du Proche ou du Moyen Orient agiraient tous de la même façon contre leurs ennemis. Au contraire, dans ces Etats, on se serait étonné de voir un procès trainer en longueur. De plus, Ousama Ben Laden aurait pu dire des choses très compromettantes pour les Américains. D’autres gouvernements, y compris en Europe (sauf bien sûr en Allemagne…), auraient d’ailleurs agi exactement de la même façon que les Américains.

Q. : Pendant des années, Ben Laden a pu vivre tranquillement au Pakistan. Dans quelle mesure le Pakistan est-il noyauté par les islamistes ?

PSL : La popularité de Ben Laden équivaut à zéro en Afghanistan, pays à partir duquel il avait jadis déployé ses actions, parce que les gens ne le connaissent quasiment pas là-bas. Mais au Pakistan, il est désormais devenu une célébrité, parce que son élimination a été perpétrée en écornant la souveraineté pakistanaise. Le Pakistan ne reproche pas tant aux Américains d’avoir éliminé Ben Laden, mais d’avoir enfreint délibérément, et de manière flagrante, la souveraineté territoriale de leur pays, dans la mesure où Washington n’a jamais informé les autorités pakistanaises de son intention d’envoyer un commando pour liquider le chef présumé d’Al-Qaeda. C’est essentiellement cela que les Pakistanais reprochent aujourd’hui aux Américains. Cette manière d’agir est contraire à l’esprit de tout bon partenariat, un partenariat que l’on dit exister entre les Etats-Unis et leur allié pakistanais.

(entretien paru dans « zur Zeit », Vienne, n°21/2011 ; http://www.zurzeit.at/ ; trad.. franc. : Robert Steuckers).

00:25 Publié dans Actualité | Lien permanent | Commentaires (3) | Tags : monde arabe, monde arabo musulman, lbye, afrique du nord, afrique, affaires africaines, politique internationale, méditerranée, géopolitique, islamisme, ben laden, pakistan, etats-unis, otan, entretiens |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Krantenkoppen - Mei 2011 (7)

Die ‘magere’ is Alic Fikret, een man met een aangeboren afwijking. Hij komt glimlachend, als uitverkorene, tot tegen de draad gewandeld. Die glimlach is natuurlijk niet meer te zien op de gemonteerde beelden die de wereld rond gingen.

Na montage lijkt het erop dat een groep uitgemergelde mensen zich tegen de draad drukt, reikend naar de vrijheid. Het beeld roept een associatie op met de concentratiekampen van de Nazi’s. Het kon niet anders of de Serviërs waren volop bezig met een ‘Endlösung’ …"

Zij (Nederlandse ex-blauwh...elmen) hebben mij verteld dat Dutchbat eerder zichzelf moest beschermen tegen de moslims dan de moslims tegen de Serviërs. Zo heeft volgens hen bijvoorbeeld het Bosnisch-Servische leger de moslimvrouwen en -kinderen voedsel en water gebracht."

00:20 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, politique internationale, flandre, pays-bas, europe, affaires européennes, journaux, médias, presse |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

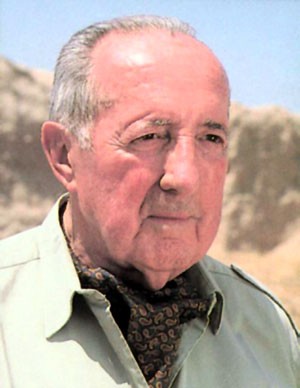

Fuad Rifka est mort...

Fuad Rifka est mort…

L’hebdomadaire allemand Der Spiegel annonce discrètement le décès, survenu le 14 mai dernier dans sa quatre-vingt-unième année. Né sur la frontière entre la Syrie et le Liban, Fuad Rifka avait étudié à Tübingen dans les années 60. Der Spiegel rappelle ses paroles : « Mon séjour à Tübingen a été comme un séisme dans mon existence ». Après de bonnes études de philosophie, il passe dans cette ville universitaire du Baden-Würtemberg une thèse de doctorat sur l’esthétique selon Martin Heidegger puis retourne au Liban en 1966 pour y enseigner ce que l’on appelait là-bas la « philosophie occidentale » et pour poursuivre sa belle carrière de poète. Avant de partir pour l’Allemagne, il avait cofondé une revue d’avant-garde à Beyrouth, Shi’r, dont l’objectif était de révolutionner la poésie de langue arabe. Outre la publication de ses superbes recueils de poésie, Fuad Rifka a composé une anthologie de la poésie allemande du 20ème siècle et a traduit les œuvres de Hölderlin, de Trakl, de Rilke, de Novalis et de Goethe en arabe, ce qui lui a valu d’être nommé membre correspondant de l’Académie allemande de la langue et des lettres. Le monde arabe vient de perdre son germaniste le plus sublime, en même temps qu’un poète bilingue arabe/allemand d’une exceptionnelle qualité qui, peut-être mieux que les germanophones eux-mêmes, a su traduire en vers l’idée cardinale de son maître Heidegger, celle de la sérénité, de la Gelassenheit, face aux éléments et à la nature.

(source : Der Spiegel, n°21/2011).

00:15 Publié dans Hommages, Littérature | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : monde arabe, liban, allemagne, heidegger, fuad rifka, littérature, lettres, poésie, poésie arabe, poésie allemande, littérature allemande, littérature arabe, lettres arabes, lettres allemandes |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Wertvollzug

Wertvollzug

WertvollzugCarl Schmitt, Die Tyrannei der Werte, 1960.

00:05 Publié dans Philosophie, Révolution conservatrice, Théorie politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : carl schmitt, philosophie, théorie politique, sciences politiques, politologie, révolution conservatrice |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

lundi, 30 mai 2011

China: The New bin Laden

China: The New bin Laden

Ex: http://www.lewrockwell.com/

Recently by Paul Craig Roberts: Americans Are Living In 1984

George Orwell, the pen name by which Eric Blair is known, had the gift of prophecy, or else blind luck. In 1949 in his novel, 1984, he described the Amerika of today and, I fear, also his native Great Britain, which is no longer great and follows Washington, licking the jackboot and submitting to Washington’s hegemony over England and Europe and exhausting itself financially and morally in order to support Amerikan hegemony over the rest of the world.

In Orwell’s prophecy, Big Brother’s government rules over unquestioning people, incapable of independent thought, who are constantly spied upon. In 1949 there was no Internet, Facebook, twitter, GPS, etc. Big Brother’s spying was done through cameras and microphones in public areas, as in England today, and through television equipped with surveillance devices in homes. As everyone thought what the government intended for them to think, it was easy to identify the few who had suspicions.

Fear and war were used to keep everyone in line, but not even Orwell anticipated Homeland Security feeling up the genitals of air travelers and shopping center customers. Every day in people’s lives, there came over the TV the Two Minutes of Hate. An image of Emmanuel Goldstein, a propaganda creation of the Ministry of Truth, who is designated as Oceania’s Number One Enemy, appeared on the screen. Goldstein was the non-existent "enemy of the state" whose non-existent organization, "The Brotherhood," was Oceania’s terrorist enemy. The Goldstein Threat justified the "Homeland Security" that violated all known Rights of Englishmen and kept Oceania’s subjects "safe."

Since 9/11, with some diversions into Sheik Mohammed and Mohamed Atta, the two rivals to bin Laden as the "Mastermind of 9/11," Osama bin Laden has played the 21st century roll of Emmanuel Goldstein. Now that the Obama Regime has announced the murder of the modern-day Goldstein, a new demon must be constructed before Oceania’s wars run out of justifications.

Hillary Clinton, the low-grade moron who is US Secretary of State, is busy at work making China the new enemy of Oceania. China is Amerika’s largest creditor, but this did not inhibit the idiot Hilary from, this week in front of high Chinese officials, denouncing China for "human rights violations" and for the absence of democracy.

While Hilary was enjoying her rant and displaying unspeakable Amerikan hypocrisy, Homeland Security thugs had organized local police and sheriffs in a small town that is the home of Western Illinois University and set upon peaceful students who were enjoying their annual street party. There was no rioting, no property damage, but the riot police or Homeland Security SWAT teams showed up with sound cannons, gassed the students and beat them.

Indeed, if anyone pays any attention to what is happening in Amerika today, a militarized police and Homeland Security are destroying constitutional rights of peaceful assembly, protest, and free speech.

For practical purposes, the U.S. Constitution no longer exists. The police can beat, taser, abuse, and falsely arrest American citizens and experience no adverse consequences.

The executive branch of the federal government, to whom we used to look to protect us from abuses at the state and local level, acquired the right under the Bush regime to ignore both US and international law, along with the US Constitution and the constitutional powers of Congress and the judiciary. As long as there is a "state of war," such as the open-ended "war on terror," the executive branch is higher than the law and is unaccountable to law. Amerika is not a democracy, but a country ruled by an executive branch Caesar.

Hillary, of course, like the rest of the U.S. Government, is scared by the recent International Monetary Fund (IMF) report that China will be the most powerful economy in five years.

Just as the military/security complex pressured President John F. Kennedy to start a war with the Soviet Union over the Cuban missile crisis while the US still had the nuclear advantage, Hillary is now moving China into the role of Emmanuel Goldstein.

Hate has to be mobilized, before Washington can move the ignorant patriotic masses to war.

How can Oceania continue if the declared enemy, Osama bin Laden, is dead. Big Brother must immediately invent another "enemy of the people."

But Hillary, being a total idiot, has chosen a country that has other than military weapons. While the Amerikans support "dissidents" in China, who are sufficiently stupid to believe that democracy exists in Amerika, the insulted Chinese government sits on $2 trillion in US dollar-denominated assets that can be dumped, thus destroying the US dollar’s exchange value and the dollar as reserve currency, the main source of US power.

Hillary, in an unprecedented act of hypocrisy, denounced China for "human rights violations." This from a country that has violated the human rights of millions of victims in our own time in Iraq, Afghanistan, Pakistan, Yemen, Libya, Somalia, Abu Ghraib, Guantanamo, secret CIA prisons dotted all over the planet, in US courts of law, and in the arrests and seizure of documents of American war protestors. There is no worst violator of human rights on the planet than the US government, and the world knows it.

The hubris and arrogance of US policymakers, and the lies that they inculcate in the American public, have exposed Washington to war with the most populous country on earth, a country that has a military alliance with Russia, which has sufficient nuclear weapons to wipe out all life on earth. The scared idiots in Washington are desperate to set up China as the new Osama bin Laden, the figure of two minutes of hate every news hour, so that the World’s Only Superpower can take out the Chinese before they surpass the US as the Number One Power.

No country on earth has a less responsible government and a less accountable government than the Americans. However, Americans will defend their own oppression, and that of the world, to the bitter end.

May 16, 2011

Paul Craig Roberts [send him mail], a former Assistant Secretary of the US Treasury and former associate editor of the Wall Street Journal, has been reporting shocking cases of prosecutorial abuse for two decades. A new edition of his book, The Tyranny of Good Intentions, co-authored with Lawrence Stratton, a documented account of how Americans lost the protection of law, has been released by Random House.

Copyright © 2011 Paul Craig Roberts

00:29 Publié dans Actualité | Lien permanent | Commentaires (2) | Tags : politique internationale, chine, etats-unis, actualité, géopolitique, pacifique, asie, affaires asiatiques |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Krantenkoppen - Mei 2011 (6)

http://www.ftm.nl/original/rebellen-van-de-eerlijke-cola.aspx

De reactie van de supermarkten – ze willen van besmet kippenvlees af – vond ik hypocriet en exemplarisch voor de gecorrumpeerde voedselindustrie. Natuurlijk, wie niet? Maar begin eens met normale prijzen te betalen. Kip is de afgelopen 50 jaar immers alleen maar goedkoper geworden."

00:17 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : presse, journaux, médias, politique internationale, actualité, europe, affaires européennes, flandre, pays-bas |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Point de situation

Point de situation

Ex: http://lepolemarque.blogspot.com/

Le professeur Bernard Wicht, dont les Éditions Le Polémarque ont publié dernièrement l’essai Une nouvelle Guerre de Trente Ans ?, intervient de manière régulière en séances théoriques dans le cadre des formations proposées par l’association NDS* pour le développement des techniques de défense citoyenne. Diffusés sous forme de fiches synthétiques et remaniés en permanence, ces cours feront dès la rentrée de septembre 2011 l’objet de la nouvelle collection « Paysages Stratégiques » des Éditions Le Polémarque. Son ambition, modeste dans ses moyens mais réelle en terme d’impact, sera d’apporter aux lecteurs soucieux d’affronter les transformations structurelles irréversibles à l’œuvre à l’intérieur de notre société (B. Wicht parle sans détour de « la fin de l’ancien monde », annoncée par « la fin de l’État moderne »), les armes conceptuelles nécessaires pour mieux comprendre notre époque, afin de mieux la surmonter**.

Le « point de situation » que nous reproduisons ci-dessous, avec l’aimable autorisation de NDS, résume l’orientation générale du projet.

L. Schang

* Neurone Défense Système (nds-ch.org). Pour joindre son alter ego français, l’ACDS (Académie du Couteau et de la Défense en Situation), voir le site acds-fr.org.

Point de situation

1) C’est la fin de l’État moderne et des institutions qu’il a créés et qui le portent : armée, université, système éducatif national, etc.

2) C’est la fin de l’ère industrielle et des formes d’organisation hiérarchique et pyramidale dont elle a accouché : des grandes usines aux grandes banques (d’où une démassification et une sorte de « démodernisation »).

3) C’est l’avènement de la société de l’information : structures plus petites et « sans tête », l’idée compte plus que l’organisation et l’institution, les nouvelles élites sont déjà au travail (mais on ne les voit pas parce qu’on ne regarde pas au bon endroit : principe de celui qui cherche ses clefs sur le réverbère plutôt que là où il les a perdues).

Dans cette perspective, il faut considérer :

- que l’effondrement actuel du Maghreb et du Moyen-Orient va accélérer la fin de l’ancien monde et l’avènement du nouveau (avec tous les bouleversements que cela suppose, en particulier en Europe) ;

- que se battre sur des positions déjà submergées (telles que universités, grandes écoles, armée est un gaspillage de temps et d’énergie ;

- qu’il faut s’efforcer de travailler en fonction des nouveaux paradigmes : nouvelles formes d’organisation, nouvelles méthodes de travail (selon les principes : « créer la culture, donner des moyens, laisser faire le travail » ; « travailler dans la marge d’erreur du système (actuel) » ; « (dans le contexte actuel) le salut vient des marges ; « loi des petits nombres (en lieu et place de l’ère des masses) ».

À titre d’exemple, de petites structures (souvent peu formalisées) se montrent de plus en plus aptes à développer des idées fortes, précisément parce qu’elles agissent « en dehors » (non pas contre) du système et qu’elles ne sont pas liées à l’establishment. Ce sont leurs projets qui font se rencontrer des gens ne se connaissant pas mais qui pourtant se font immédiatement confiance. Elles agissent le plus souvent par capillarité, selon le principe de « l’inoculée conception », et ont un écho et un impact inversement proportionnels à leur taille et à leur moyens.

Aujourd’hui, c’est ce type de structures qui permet de faire avancer tant la réflexion que les pratiques et la production : on peut ainsi citer en vrac les blogs, les start-up, les petites coopératives, etc. − NDS et Le Polémarque notamment, s’inscrivent dans une telle dynamique.

Bernard Wicht

00:15 Publié dans Actualité, Philosophie, Polémologie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : philosophie, polémologie, problèmes contemporains, futurologie |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

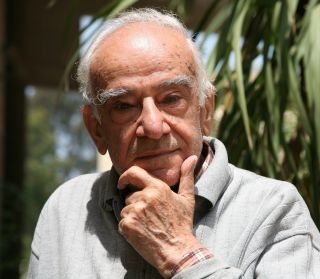

Elsa Darciel en Francis Parker Yockey: De Vlaamse danslegende

Elsa Darciel en Francis Parker Yockey: De Vlaamse danslegende

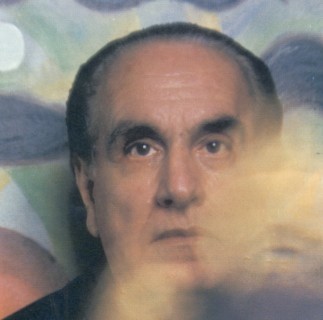

Prof. Dr. Piet TOMMISSEN

Ex: http://mededelingen.over-blog.com/

Elsa (niet: Elza) Dewette zag op 12 april 1903 te Sint-Amandsberg bij Gent het levenslicht. Ze was de kleindochter van Eduard Blaes (1846-1909), een verdienstelijke componist, dirigent en muziekleraar, bij wie haar vader pianoles had gevolgd. Afgaande op haar eigen getuigenis hoorde ze haar vader en haar grootvader vaak discuteren over de filosoof Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), over de dichter Heinrich Heine (1797-1856) en over de beroemde componist Richard Wagner (1813-1883). Volgens haar latere leerling Oscar Van Malder, zouden die discussies "een diepgaande invloed uitoefenen op haar later leven en werken"; verheft hij een hypothese niet tot de rang van een feit?

Elsa (niet: Elza) Dewette zag op 12 april 1903 te Sint-Amandsberg bij Gent het levenslicht. Ze was de kleindochter van Eduard Blaes (1846-1909), een verdienstelijke componist, dirigent en muziekleraar, bij wie haar vader pianoles had gevolgd. Afgaande op haar eigen getuigenis hoorde ze haar vader en haar grootvader vaak discuteren over de filosoof Friedrich Nietzsche (1844-1900), over de dichter Heinrich Heine (1797-1856) en over de beroemde componist Richard Wagner (1813-1883). Volgens haar latere leerling Oscar Van Malder, zouden die discussies "een diepgaande invloed uitoefenen op haar later leven en werken"; verheft hij een hypothese niet tot de rang van een feit?

Vader Dewette, ingenieur van opleiding en onderdirecteur bij de Telefoon te Brussel, kreeg bij het uitbreken van W.O. I het bevel, de plannen van het telefoonnet van de provincie Brabant in veiligheid te brengen. Dat verklaart wellicht waarom hij met zijn gezin naar Engeland is uitgeweken. In ieder geval vestigde hij zich na heel wat ronddolen in een woning in een buitenwijk van Londen. Via een zus van de later wereldberoemd geworden historicus Arnold Toynbee (1889-1975), een goede bekende van vader Dewette, geraakte Elsa op de elitaire Kensington Highschool.

Haar peter, de bekende etser Jules De Bruycker (1870-1945), bewoonde hetzelfde gebouw als het gezin Dewette; hij enthousiasmeerde Elsa voor de plastische kunsten. Anderzijds schijnt de eminente Zwitserse avant-garde kunstenaar Emile Jaques-Dalcroze (1865-1950) haar op school het abc van de muziek én de basisgedachten van de eurytmie te hebben bijgebracht. Pianoles volgde ze bij miss Barber, een oud-leerlinge van de grote Johannes Brahms (1833-1897) en verwant met de Amerikaanse componist Samuel Barber (1910-1981). Doch die artistieke impulsen verhinderden haar blijkbaar niet, zich voor de exacte wetenschappen te interesseren. In een interview vertelde ze het ingangsexamen chemie van de universiteit van Londen probleemloos overleefd te hebben.

Elsa bleef na de oorlog nog een jaar in Londen, om haar middelbare studies af te sluiten. Helaas werd dat einddiploma in België niet erkend. Van lieverlede kwam ze in een Franstalige Brusselse school terecht en dat werd een fiasco, want in Engeland had ze haar Frans verleerd! In oktober 1920 schakelde ze over naar de (eveneens Franstalige) Academie en volgde er drie jaar tereke als dagstudente de lessen van de in Watermaal-Bosvoorde woonachtige symbolistische schilder Constant Montald (1862-1946). Op een bepaald ogenblik kreeg August Vermeylen (1872-1945) het er zwaar te verduren: zijn inzet voor de vernederlandsing van de Gentse universiteit werd door zijn franskiljonse collegae, waaronder de beroemde architect Victor Horta (1861-1947), de directeur, niet geappreciëerd. Elsa nam het voor hem op en werd aldus van vandaag op morgen populair in Vlaamse studentenmiddens: ze werd tot penningmeester van de afdeling Brussel van het Diets Studentenverbond gebombardeerd, een functie die ze vier jaar heeft waargenomen.

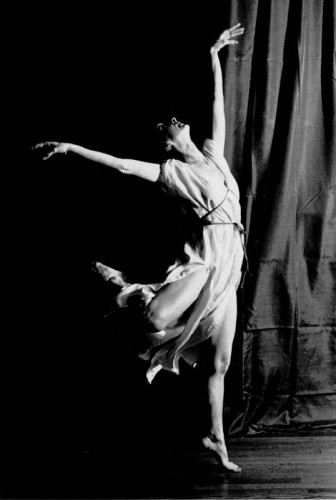

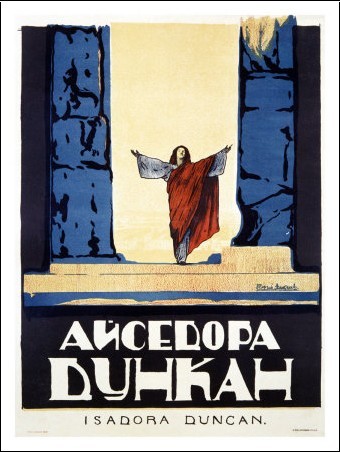

Van 1924 tot in 1931 was Elsa Dewette als tekenares tewerk gesteld bij een weekblad voor dames, voor hetwelk ze tevens de bekende acteur Douglas Fairbanks (ps. van Elton Ulman; 1883-1939) en de als "de kleine verloofde van Amerika" bekend staande actrice Mary Pickford (ps. van Gladys Smith; 1893-1979) geïnterviewd heeft. In 1922 gebeurde echter iets dat haar leven een beslissende wending zou geven: toevallig woonde ze in de Parkschouwburg te Brussel een optreden bij van Isadora Duncan (1877-1927). De schok was dermate groot dat ze daarna drie dagen met koorts te bed heeft gelegen!

De gracieuze bewegingen van Isadora Duncan, waarin de danseres als het ware haar ziel blootlegde, konden de zich voor danskunst interesserende Elsa Dewette niet onverschillig laten; ze realiseerde zich te maken te hebben met een concrete toepassing van de danshervorming die Jean Georges Noverre (1727-1810) gepredikt en wiens Lettres sur la danse et sur les ballets (1760) ze bestudeerd had. Na de danseres in Brussel aan het werk te hebben gezien, heeft ze met haar een paar gesprekken gevoerd op haar kamer in het Brusselse hotel Métropole aan het de Brouckèreplein. Meer nog: met de opbrengst van de verkoop van geërfde aandelen kon ze in 1927 in Nice bij haar idool dansles volgen. Wie weet hoe haar leven zou verlopen zijn, mocht de beroemde sterdanseres niet in de loop van datzelfde jaar zijn overleden?

Elsa's besluit lag hoe dan ook reeds vast: ze wou en ze zou met een eigen dansschool van start gaan. De ouders waarschuwden haar: waarom een veilig bestaan aan een onzekere toekomst opofferen? Vandaar dat het tot 1930 geduurd heeft alvorens de grote stap gezet werd. Aan de Folkwangschule in Essen heeft ze een zomercursus gevolgd bij Kurt Jooss (1901-1979), eerst leerling en dan assistent van Rudolf Laban von Vàralja, beter beken als Rudolf von Laban (1879-1958), wiens theorie hij in de de praktijk toepaste; ze was vergezeld van twee dames die in Vlaanderen ook hun weg als danseres hebben gemaakt: Lea Daan (ps. van Paula Gombert; 1906-1995) en Isa Voss (ps. van Maria Voorspoels; 1909-1939).

In 1930 bracht Elsa op de voorgevel van haar woning (Kruisstraat 8 te Elsene) een koperen plaat aan met de indicatie: "Elsa Darciel - School voor Eurythmie". Bijgevolg moet ze rond die tijd voor het pseudoniem Darciel geopteerd hebben. Sommige auteurs beweren dat die schuilnaam door haar leerlingen bedacht werd. Elsa's eigen versie klinkt logischer: de naam zou afgeleid zijn van d'Arcielle, de naam van een oud-tante die in de tijd van de Franse Revolutie leefde.

Toen in 1932 vrij regelmatig gemiddeld vijftien leerlingen opdaagden, besloot de nieuwbakken Darciel alles op alles te zetten: ze huurde in Brussel de zaal van het Paleis voor Schone Kunsten (thans: Bozar) af! Maurits Wynants schrijft: "Het werd een triomf." Geen wonder dat ze de krachttoer in 1934 herhaalde, dit keer met een eigen creatie van het ballet Heer Halewijn op muziek van de door de musicoloog Charles Van den Borren (1872-1966) aangepaste Boergondische Hofdansen. De pers jubelde: "Een nieuwe vorm van dans met internationale allures is in België geboren."

Daarna volgde de grote stap, die erop gericht was gans Vlaanderen te veroveren. Met Herman Teirlinck (1879-1967) als animator begon in Aalst een ware triomftocht. Het heeft geen zin de vele successen op te sommen, daar ze in de kranten breed uitgesmeerd zijn geworden. De uitzondering bevestigt de algemene regel en dus maak ik twee uitzonderingen: in 1939 voerden op de Grote Markt te Kortrijk 1.500 danseressen en dansers 10 dagen lang het Vredesspel op en in 1944 grepen talrijke opvoeringen van Tijl Uilenspiegel op muziek van Richard Strauss (1864-1949) plaats. Bij de Bevrijding kende haar vader moeilijkheden omdat een hogere Duitse officier hem een bezoek had gebracht (cf. infra). Zij zelf reisde begin 1946 naar de U.S.A., bezocht er in diverse steden familieleden en vrienden, en hield lezingen in de Engelse taal (cf. infra).

Daarna volgde de grote stap, die erop gericht was gans Vlaanderen te veroveren. Met Herman Teirlinck (1879-1967) als animator begon in Aalst een ware triomftocht. Het heeft geen zin de vele successen op te sommen, daar ze in de kranten breed uitgesmeerd zijn geworden. De uitzondering bevestigt de algemene regel en dus maak ik twee uitzonderingen: in 1939 voerden op de Grote Markt te Kortrijk 1.500 danseressen en dansers 10 dagen lang het Vredesspel op en in 1944 grepen talrijke opvoeringen van Tijl Uilenspiegel op muziek van Richard Strauss (1864-1949) plaats. Bij de Bevrijding kende haar vader moeilijkheden omdat een hogere Duitse officier hem een bezoek had gebracht (cf. infra). Zij zelf reisde begin 1946 naar de U.S.A., bezocht er in diverse steden familieleden en vrienden, en hield lezingen in de Engelse taal (cf. infra).

Na haar terugkeer einde 1947 begon - dixit Jacques De Leger (°1932) - "haar belangrijkste creatieve periode". Inderdaad, van 1952 af trad ze, dit keer in opdracht van de dienst Volksontwikkeling, overal in den lande op en monteerde ze balletuitzendingen voor de televisie. Bovendien gaf ze aan diverse scholen onderricht in bewegingsleer. In 1965 hield ze het voor bekeken: ze had in de loop der voorbije 35 jaar niet minder dan 400 balletavonden georganiseerd en zowat 35 grote balletten gecreëerd! Doch zonder dralen vatte ze de studie van de Spaanse taal aan, die ze na vijf jaar afsloot. Ook maakte ze van een haar in december 1963 door de universiteit van Cambridge afgeleverd diploma gebruik om geïnteresseerde E.E.G.- ambtenaren Engels bij te brengen.

Op 89-jarige leeftijd werd in Tervuren haar huurcontract opgezegd en stond Elsa op straat. Toen heeft iemand ervoor gezorgd dat haar archief niet op het stort belandde.

Zelf belandde ze op een eenpersoonskamer in Ukkel, terwijl haar bezittingen (vooral de bibliotheek) bij een hulpvaardige ziel terechtkwamen en sindsdien verdwenen zijn. Uiteindelijk kwam ze in het rusthuis Weyveldt in Hofstade (bij Aalst) terecht, alwaar ze begin 1998 vreedzaam overleden is.

Deze aflevering steunt uitsluitend op de voortreffelijke biografie van K. Coogan, Dreamer of the Day. Francis Parker Yockey and the Postwar Fascist International (Brooklyn, NY: Autonomedia, 1999, 644 p.)

F.P. Yockey werd in 1917 in Chicago geboren. Al vroegtijdig ontpopte hij zich als een goede pianist en gold hij als een begaafde humorist. In de herfst van 1934 kwam hij op de University of Michigan (Ann Arbor) terecht. Hier werd hij uit een Saulus een Paulus, d.w.z. hij gaf zijn pro-communistische overtuiging prijs en werd bij wijze van spreken een Amerikaanse nazi. Die ommezwaai wordt toegeschreven aan zijn lectuur van Der Untergang des Abendlandes, het tweedelige opus magnum van de Duitse historicus en niet-nazi Oswald Spengler (1880-1936), doch het is een uitgemaakte zaak dat hij door de spengleriaans getinte Kulturgeschichte der Neuzeit (3 delen; 1927-31) van de Oostenrijkse Jood Egon Friedell (eig. Friedmann; 1878-1938 [zelfmoord]) tot de overtuiging was gekomen, dat niet materiële factoren, doch ideeën het historisch verloop bepalen. De ironie van het lot heeft dus gewild dat twee eminente Europese niet-nazis onrechtstreeks een Amerikaanse nazi hebben voortgebracht!

F.P. Yockey werd in 1917 in Chicago geboren. Al vroegtijdig ontpopte hij zich als een goede pianist en gold hij als een begaafde humorist. In de herfst van 1934 kwam hij op de University of Michigan (Ann Arbor) terecht. Hier werd hij uit een Saulus een Paulus, d.w.z. hij gaf zijn pro-communistische overtuiging prijs en werd bij wijze van spreken een Amerikaanse nazi. Die ommezwaai wordt toegeschreven aan zijn lectuur van Der Untergang des Abendlandes, het tweedelige opus magnum van de Duitse historicus en niet-nazi Oswald Spengler (1880-1936), doch het is een uitgemaakte zaak dat hij door de spengleriaans getinte Kulturgeschichte der Neuzeit (3 delen; 1927-31) van de Oostenrijkse Jood Egon Friedell (eig. Friedmann; 1878-1938 [zelfmoord]) tot de overtuiging was gekomen, dat niet materiële factoren, doch ideeën het historisch verloop bepalen. De ironie van het lot heeft dus gewild dat twee eminente Europese niet-nazis onrechtstreeks een Amerikaanse nazi hebben voortgebracht!

Wat er ook van zij, in 1936 schakelde Yockey over naar de katholieke Georgetown University (Washington); hij immatriculeerde in het aan deze universiteit verbonden Center for Strategic and International Studies. Als reden geeft Coogan zijn belangstelling op voor het verband tussen internationaal recht en buitenlandse politiek. Meteen begon hij zich te begeesteren voor de geopolitiek, meer bepaald voor de doctrine die Karl Haushofer (1869-1946) verkondigde en die door één van zijn professoren, de pater jezuïet Edmund Aloysius Walsh (1885-1956), bestreden werd. Interessant om weten: diezelfde pater doceerde ook - andermaal afwijzend - over de theorieën van de hoger vermelde Carl Schmitt. Voor de tweede keer zorgde de ironie van het lot voor een verrassing: na W.O. II heeft Yockey zowel Haushofer als Schmitt misbruikt.

Zijn diploma behaalde Yockey cum laude in 1941 aan de rechtsfaculteit van de door jezuïeten gerunde Loyola University (Chicago), na tussendoor aan de Northwestern Law School (Chicago) college te hebben gelopen. Al dan niet onder schuilnaam geraakte hij bij rechtse initiatieven betrokken. Er mag niet uit het oog worden verloren dat rechts en zelfs fascisme op dat ogenblik ook in de U.S.A. nogal wat aanhangers hadden; het is denkbaar dat de optie van de wereldwijd bewonderde industrieel Henry Ford (1863-1947) en deze van de zeer populaire vliegenier Charles Lindbergh (1902-1974) daar niet vreemd aan zijn geweest.

Zoals talloze Amerikanen was Yockey gekant tegen de Amerikaanse militaire interventie, wat hem niet belet heeft in mei 1942 soldaat te worden. Maar in "een lijst van deloyale of subversieve personen die door het Sixth Service Command ervan verdacht werden nazis te zijn" figureert Yockeys naam! Op de begrijpelijke vraag "Was Yockey een nazi-spion?" antwoordt Coogan voorzichtig, dat het er de schijn van heeft, dat hij geen "spion in de gebruikelijke zin van het woord" was. Hij is twee maanden voortvluchtig geweest (in de terminologie van het Amerikaanse leger: AWOL = Absent Without Official Leave - in mijn ogen een eufemisme). Niettemin werd hem om geneeskundige redenen op 13 juli 1943 eervol ontslag verleend.

Anno 1946 kreeg Yockey een job aangeboden in een rechtbank in Wiesbaden die zich over de oorlogsmisdaden van tweederangsnazis uit te spreken had.

Het staat nu wel vast dat zijn door zijn overste genoteerde chronisch absenteïsme te maken had én met zwarte-markt-praktijken (sigaretten!) én met het schrijven van artikels tegen de legitimiteit van de processen van Nürnberg. Eind november 1946 werd hij aan de deur gezet. Reeds in 1947 was Yockey evenwel terug in Europa: in het Ierse dorp Brittas Bay schreef hij in zes maanden Imperium. The Philosophy of History and Politics, dat hij onder het pseudoniem Ulrick Varange uitgaf.

Ik verzaak aan een poging om dit inhoudelijk zonder Spengler, Schmitt en Haushofer ondenkbaar opus in enkele regels te willen samenvatten. Over de vaak in de illegaliteit opererende neo-nazistische organisaties, die in een soort van Internationale schijnen te hebben samengewerkt, ga ik het evenmin hebben. Niet eens Yockeys curieuze samenwerking met senator Joe McCarthy (1908-1957), de man van de anti-communistische kruistocht in de U.S.A. (mccarthysm) die zelfs de filmacteur Charles Spencer Chaplin (1889-1977) niet spaarde, zijn gesprekken met groten der aarde zoals de Egyptische president Gamel Abdul Nasser (1918-1970) breng ik te berde, zomin als zijn poging om op Cuba Fidel Castro (°1927) te ontmoeten. Het zijn stuk voor stuk themata die niets te zien hebben met het onderwerp van mijn bijdrage. Doch ik kan onder dit sub-kapittel geen streep trekken zonder iets te hebben gezegd over Yockeys einde.