Baron Julius Evola (1899-1974) was an important Italian intellectual, although he despised the term. As poet and painter, he was the major Italian representative of Dadaism (1916-1922). Later he became the leading Italian exponent of the intellectually rigorous esotericism of René Guénon (1886-1951). He enjoyed an international reputation as the author of books on magic, alchemy and eastern religious traditions and won the respect of such important scholars as Mircea Eliade and Giuseppe Tucci. His book on early Buddhism, The Doctrine of Awakening,[1] which was translated in 1951, established his reputation among English-speaking esotericists. In 1983, Inner Traditions International, directed by Ehud Sperling, published Evola’s 1958 book, The Metaphysics of Sex, which it reprinted as Eros and the Mysteries of Love in 1992, the same year it published his 1949 book on Tantra, The Yoga of Power.[2]

Baron Julius Evola (1899-1974) was an important Italian intellectual, although he despised the term. As poet and painter, he was the major Italian representative of Dadaism (1916-1922). Later he became the leading Italian exponent of the intellectually rigorous esotericism of René Guénon (1886-1951). He enjoyed an international reputation as the author of books on magic, alchemy and eastern religious traditions and won the respect of such important scholars as Mircea Eliade and Giuseppe Tucci. His book on early Buddhism, The Doctrine of Awakening,[1] which was translated in 1951, established his reputation among English-speaking esotericists. In 1983, Inner Traditions International, directed by Ehud Sperling, published Evola’s 1958 book, The Metaphysics of Sex, which it reprinted as Eros and the Mysteries of Love in 1992, the same year it published his 1949 book on Tantra, The Yoga of Power.[2]

The marketing appeal of the topic of sex is obvious. Both books, however, are serious studies, not sex manuals. Since then Inner Traditions has reprinted The Doctrine of Awakening and published many of Evola’s esoteric books, including studies of alchemy and magic,[3] and what Evola himself considered his most important exposition of his beliefs, Revolt Against the Modern World.[4]

In Europe Evola is known not only as an esotericist, but also as a brilliant and incisive right-wing thinker. During the 1980s most of his books, New Age and political, were translated into French under the aegis of Alain de Benoist, the leader of the French Nouvelle Droite.[5] Books and articles by Evola have been translated into German and published in every decade since the 1930s.[6]

Discussion of Evola’s politics reached North America slowly. In the 1980s political scientists Thomas Sheehan, Franco Ferraresi, and Richard Drake wrote about him unsympathetically, blaming him for Neo-Fascist terrorism.[7] In 1990 the esoteric journal, Gnosis, devoted part of an issue to Evola. Robin Waterfield, a classicist and author of a book on René Guénon, contributed a thoughtful appreciation of his work on the basis of French translations.[8] Italian esotericist Elémire Zolla discussed Evola’s development accurately but ungenerously.[9] The essay by Gnosis editor Jay Kinney was driven by an almost hysterical fear of the word “Fascist.” He did not appear to have read Evola’s books in any language, called the 1983 edition of The Metaphysics of Sex Evola’s “only book translated into English” and concluded “Evola’s esotericism appears to be well outside of the main currents of Western tradition. It remains to be seen whether his Hermetic virtues can be disentangled from his political sins. Meanwhile, he serves as a persuasive argument for the separation of esoteric ‘Church and State.’”[10]

With the publication of Men Among the Ruins: Post-War Reflections of a Radical Traditionalist,[11] English speakers can read Evola’s political views for themselves. They will find that the text, in Guido Stucco’s workman-like translation, edited by Michael Moynihan, is guarded by a double firewall. Joscelyn Godwin’s “Foreword” answers Jay Kinney’s hysterical diatribe of 1990. Godwin defends publishing Evola’s political writings by an appeal to “academic freedom,” which works “with the tools of rationality and scholarship, unsullied by emotionality or subjective references” and favors making all of Evola’s works available because “it would be academically dishonest to suppress anything.” Godwin’s high praise for The Doctrine of Awakening implicitly condemns Kinney’s ignorance. Evola’s books on esoteric topics reveal “one of the keenest minds in the field . . . The challenge to esotericists is that when Evola came down to earth, he was so ‘incorrect’ – by the received standards of our society. He was no fool; and he cannot possibly have been right . . . so what is one to make of it?”

Godwin’s “Preface” is followed by an introduction of more than 100 pages by Austrian esotericist H. T. Hansen on “Julius Evola’s Political Endeavors,” translated from the 1991 German version of Men Among the Ruins,[12] with additional notes and corrections (called “Preface to the American Edition”). Hansen’s introduction to Revolt Against the Modern World[13] is, with Robin Waterfield’s Gnosis essay, the best short introduction to Evola in English. His longer essay is essential for serious students, and Inner Traditions deserves warm thanks for publishing it. The major book on Evola is Christophe Boutin, Politique et Tradition: Julius Evola dans le siècle (1898-1974).[14]

Readers of books published by Inner Traditions might have guessed Evola’s politics. The Mystery of the Grail,[15] first published in 1937, praises the Holy Roman Empire as a great political force, led by Germans and Italians, which tried to unite Europe under the Nordic Ghibellines. Esotericists will probably guess that the title of Revolt Against the Modern World is an homage to Crisis of the Modern World,[16] the most accessible of René Guénon’s many books. The variation is also a challenge. Evola and Guénon see the modern world as the fulfillment of the Hindu Kali Yuga, or Dark Age, that will end one cosmic cycle and introduce another. For Guénon the modern world is to be endured, but Evola believed that real men are not passive. His praise of “The World of Tradition” with its warrior aristocracies and sacral kingship is peppered with contempt for democracy, but New Age writers often make such remarks, just as scientists do. If you believe you know the truth, it is hard not to be contemptuous of a system that determines matters by counting heads and ignores the distinction between the knowledgeable and the ignorant.

Visionary Among Italian Conservative Revolutionaries

Evola was not only an important figure in Guénon’s Integral Traditionalism, but also the leading Italian exponent of the Conservative Revolution in Germany, which included Carl Schmitt, Oswald Spengler, Gottfried Benn, and Ernst Jünger.[17] From 1934-43, Evola was editor of what we would now call the “op-ed” page of a major Italian newspaper (Regime Fascista) and published Conservative Revolutionaries and other right-wing and traditionalist authors.[18] He corresponded with Schmitt,[19] translated Spengler’s Decline of the West and Jünger’s An der Zeitmauer (At the Time Barrier) into Italian and wrote the best introduction to Jünger’s Der Arbeiter (The Worker), “The Worker” in Ernst Jünger’s Thought.[20]

Spengler has been well served by translation into English, but other important figures of the Conservative Revolution had to wait a long time. Carl Schmitt’s major works have been translated only in the past few decades.[21] Jünger’s most important work of social criticism, Der Arbeiter, has never been translated.[22] The major scholarly book on the movement has never been translated, either.[23] It is a significant statement on the limits of expression in the United States that so many leftist mediocrities are published, while major European thinkers of the rank of Schmitt, Jünger, and Evola have to wait so long for translation, if the day ever comes. It is certainly intriguing that a New Age press has undertaken the translation and publishing of Evola’s books, with excellent introductions.

The divorced wife of a respected free market economist once remarked to me, “Yale used to say that conservatives were just old-fashioned liberals.”[24] People who accept that definition will be flabbergasted by Julius Evola. Like Georges Sorel, Oswald Spengler, Whittaker Chambers, and Régis Debray, Evola insists that liberals and communists are in fundamental agreement on basic principles. This agreement is significant, because for Evola politics is an expression of basic principles and he never tires of repeating his own. The transcendent is real. Man’s knowledge of his relationship to transcendence has been handed down from the beginning of human culture. This is Tradition, with a capital T. Human beings are tri-partite: body, soul, and spirit. State and society are hierarchical and the clearer the hierarchy, the healthier the society. The worst traits of the modern world are its denial of transcendence, reductionist vision of man and egalitarianism.

These traits come together in what Evola called “la daimonìa dell’economia,” translated by Stucco as “the demonic nature of the economy.”[25] Real men exist to attain knowledge of the transcendent and to strive and accomplish heroically. The economy is only a tool to provide the basis for such accomplishments and to sustain the kind of society that permits the best to attain sanctity and greatness. The modern world denies this vision.

In both individual and collective life the economic factor is the most important, real, and decisive one . . . An economic era is already by definition a fundamentally anarchical and anti-hierarchical era; it represents a subversion of the normal order . . . This subversive character is found in both Marxism and in its apparent nemesis, modern capitalism. Thus, it is absurd and deplorable for those who pretend to represent the political ‘Right’ to fail to leave the dark and small circle that is determined by the demonic power of the economy – a circle including capitalism, Marxism, and all the intermediate economic degrees. This should be firmly upheld by those today who are taking a stand against the forces of the Left. Nothing is more evident than that modern capitalism is just as subversive as Marxism. The materialistic view of life on which both systems are based is identical.[26]

Most conservatives do not like the leftist hegemony we live under, but they still want to cling to some aspect of modernity to preserve a toehold on respectability. Evola rejected the Enlightenment project lock, stock, and barrel, and had little use for the Renaissance and the Reformation. His books ask us to take seriously the attempt to imagine an intellectual and political world that radically rejects the leftist worldview. He insists that those really opposed to the leftist regime, the true Right, are not embarrassed to use words like reactionary and counter revolutionary. If you are afraid of these words, you do not have the courage to stand up to the modern world.

He also countenances the German expression, Conservative Revolution, if properly understood. Revolution is acceptable only if it is true re-volution, a turning back to origins. Conservatism is valid only when it preserves the true Tradition. So loyalty to the bourgeois order is a false conservatism, because on the level of principle, the bourgeoisie is an economic class, not a true aristocracy. That is one reason why at the end of his life, Evola was planning a right-wing journal to be called The Reactionary, in conscious opposition to the leading Italian conservative magazine, Il Borghese, “The Bourgeois.”

For Evola the state creates the nation, not the opposite. Although Evola maintained a critical distance from Fascism and never joined the Fascist Party,[27] here he was in substantial agreement with Mussolini and the famous article on “Fascism” in the Enciclopedia Italiana, authored by the philosopher and educator, Giovanni Gentile. He disagreed strongly with the official philosophy of 1930’s Germany. The Volk is not the basis of a true state, an imperium. Rather the state creates the people. Naturally, Evola rejected Locke’s notion of the Social Contract, where rational, utilitarian individuals come together to give up some of their natural rights in order to preserve the most important one, the right to property. Evola also disagreed with Aristotle’s idea that the state developed from the family. The state was created from Männerbünde, disciplined groups entered through initiation by men who were to become warriors and priests. The Männerbund, not the family, is the original basis of true political life.[28]

Evola saw his mission as finding men who could be initiated into a real warrior aristocracy, the Hindu kshatriya, to carry out Bismarck’s “Revolution from above,” what Joseph de Maistre called “not a counterrevolution, but the opposite of a revolution.” This was not a mass movement, nor did it depend on the support of the masses, by their nature incapable of great accomplishments. Hansen thinks these plans were utopian, but Evola was in touch with the latest political science. The study of elites and their role in every society, especially liberal democracies, was virtually an Italian monopoly in the first half of the Twentieth century, carried on by men like Roberto Michels, Gaetano Mosca, and Vilfredo Pareto. Evola saw that nothing can be accomplished without leadership. The modern world needs a true elite to rescue it from its involution into materialism, egalitarianism and its obsession with the economy and to restore a healthy regime of order, hierarchy and spiritual creativity. When that elite is educated and initiated, then (and only then) a true state can be created and the Dark Age will come to an end.

Egalitarianism, Fascism, Race, and Roman Catholicism

Despite his criticism of the demagogic and populist aspects of Fascism and National Socialism, Evola believed that under their aegis Italy and Germany had turned away from liberalism and communism and provided the basis for a return to aristocracy, the restoration of the castes and the renewal of a social order based on Tradition and the transcendent. Even after their defeat in World War II, Evola believed that the fight was not over, although he became increasingly discouraged and embittered in the decades after the war. (Pain from a crippling injury suffered in an air raid may have contributed to this feeling.)

Although Evola believed that the transcendent was essential for a true revival, he did not look to the Catholic Church for leadership. Men Among the Ruins was published in 1953, when the official position of the Church was still strongly anti-Communist and Evola had lived through the 1920s and 1930s when the Vatican signed the Concordat with Mussolini. So his analysis of the Church, modified but not changed for the second edition in 1967, is impressive as is his prediction that the Church would move to the left.

After the times of De Maistre, Bonald, Donoso Cortés, and the Syllabus have passed, Catholicism has been characterized by political maneuvering . . . Inevitably, the Church’s sympathies must gravitate toward a democratic-liberal political system. Moreover, Catholicism had for a long time espoused the theory of ‘natural right,’ which hardly agrees with the positive and differentiated right, on which a strong and hierarchical State can be built . . . Militant Catholics like Maritain had revived Bergson’s formula according to which ‘democracy is essentially evangelical’; they tried to demonstrate that the democratic impulse in history appears as a temporal manifestation of the authentic Christian and Catholic spirit . . . By now, the categorical condemnations of modernism and progressivism are a thing of the past . . . When today’s Catholics reject the ‘medieval residues’ of their tradition; when Vatican II and its implementations have pushed for debilitating forms of ‘bringing things up to date’; when popes uphold the United Nations (a ridiculous hybrid and illegitimate organization) practically as the prefiguration of a future Christian ecumene – this leaves no doubt in which direction the Church is being dragged. All things considered, Catholicism’s capability of providing an adequate support for a revolutionary-conservative and traditionalist movement must be resolutely denied.[29]

Although his 1967 analysis mentions Vatican II, Evola’s position on the Catholic Church went back to the 1920s, when after his early Dadaism he was developing a philosophy based on the traditions of India, the Far East and ancient Rome under the influence of Arturo Reghini (1878-1946).[30] Reghini introduced Evola to Guénon’s ideas on Tradition and his own thinking on Roman “Pagan Imperialism” as an alternative to the Twentieth Century’s democratic ideals and plutocratic reality. Working with a leading Fascist ideologue, Giuseppe Bottai (1895-1959), Evola wrote a series of articles in Bottai’s Critica Fascista in 1926-27, praising the Roman Empire as a synthesis of the sacred and the regal, an aristocratic and hierarchical system under a true leader. Evola rejected the Catholic Church as a source of religion and morality independent of the state, because he saw its universalistic claims as compatible with and tending toward liberal egalitarianism and humanitarianism, despite its anti-Communist rhetoric.

Evola’s articles enjoyed a national succès de scandale and he expanded them into a book, Imperialismo Pagano (1928), which provoked a heated debate involving many Fascist and Catholic intellectuals, including, significantly, Giovanni Battista Montini (1897-1978), who, when Evola published the second edition of Men Among the Ruins in 1967, had become the liberal Pope Paul VI. Meanwhile, Mussolini was negotiating with Pope Pius XI (1857-1939) for a reconciliation in which the Church would give its blessings to his regime in return for protection of its property and official recognition as the religion of Italy. Italy had been united by the Piedmontese conquest of Papal Rome in 1870, and the Popes had never recognized the new regime. So Evola wrote in 1928, “Every Italian and every Fascist should remember that the King of Italy is still considered a usurper by the Vatican.”[31] The signing of the Vatican Accords on February 11, 1929, ended that situation and the debate. Even Reghini and Bottai turned against Evola.[32]

Evola later regretted the tone of his polemic, but he also pointed out that the fact that this debate took place gave the lie direct to extreme assertions about lack of freedom of speech in Fascist Italy. Evola has been vindicated on the main point. The Catholic Church accepts liberal democracy and even defends it as the only legitimate regime. Notre Dame University is not the only Catholic university with a Jacques Maritain Center, but neither Notre Dame nor any other Catholic university in America has a Center named after Joseph de Maistre or Louis de Bonald or Juan Donoso Cortés. Pope Pius IX was beatified for proclaiming the doctrine of the Immaculate Conception, not for his Syllabus Errorum, which denounced the idea of coming to terms with liberalism and modern civilization.

Those who want to distance Evola from Fascism emphasize the debate over Pagan Imperialism. For several years afterwards Fascist toughs harassed Evola, until he won the patronage of Roberto Farinacci, the Fascist boss of Cremona. Evola edited the opinion page of Farinacci’s newspaper, Regime Fascista, from 1934 to 1943 in an independent fashion. Although there are anecdotes about Mussolini’s fear of Evola, the documentary evidence points in the opposite direction. Yvon de Begnac’s talks with Mussolini, published in 1990, report Mussolini consistently speaking of Evola with respect. Il Duce had the following comments about the Pagan Imperialism debate:

Despite what is generally thought, I was not at all irritated by Doctor Julius Evola’s pronouncements made a few months before the Conciliation on the modification of relations between the Holy See and Italy. Anyhow, Doctor Evola’s attitude did not directly concern relations between Italy and the Holy See, but what seemed to him the long-term irreconcilability of the Roman tradition and the Catholic tradition. Since he identified Fascism with the Roman tradition, he had no choice but to reckon as its adversary any historical vision of a universalistic order.[33]

Mussolini’s strongest support for Evola came on the subject of race, which became an issue after Italy’s conquest of Ethiopia in 1936. Influenced by Nazi Germany, Italy passed Racial Laws in 1938. Evola was already writing on the racial views consistent with a Traditional vision of mankind in opposition to what he saw as the biological reductionism and materialism of Nazi racial thought. His writings infuriated Guido Landra, editor of the journal, La Difesa della Razza (Defense of the Race). Landra and other scientific racists were especially irritated by Evola’s article, “Scientific Racism’s Mistake.”[34] Mussolini, however, praised Evola’s writings as early as 1935 and permitted Evola’s Summary of Racial Doctrine to be translated into German as Compendium of Fascist Racial Doctrine to represent the official Fascist position.[35]

Evola accepts the Traditional division of man into body, soul, and spirit and argues that there are races of all three.

While in a ‘pure blood’ horse or cat the biological element constitutes the central one, and therefore racial considerations can be legitimately restricted to it, this is certainly not the case with man, or at least any man worthy of the name . . . Therefore racial treatment of man can not stop only at a biological level.[36]

Just as the state creates the people and the nation, so the spirit forms the races of body and soul. Evola had done considerable research on the history of racial studies and wrote a history of racial thought from Classical Antiquity to the 1930’s, The Blood Myth: The Genesis of Racism.[37] Evola knew that in addition to the tradition of scientific racism, represented by Gobineau, Houston Stewart Chamberlain, Alfred Rosenberg, and Landra was one that appreciated extra- or super-biological elements and whose adherents included Montaigne, Herder, Fichte, Gustave Le Bon, and Evola’s contemporary and friend, Ludwig Ferdinand Clauss, a German biologist at the University of Berlin.[38]

Hansen has a thorough discussion of “Evola’s Attitude Toward the Jews.” Evola thought that the negative traits associated with Jews were spiritual, not physical. So a biological Jew might have an Aryan soul or spirit and biological Aryans might – and did – have a Semitic soul or spirit. As Landra saw, this was the end of any politically useful scientific racism. The greatest academic authority on Fascism, Renzo de Felice argued in The Jews in Fascist Italy that Evola’s theories are wrong, but that they have a distinguished intellectual ancestry, and Evola argued for them in an honorable way.[39] In recent years, Bill Clinton was proclaimed America’s first black president. This instinctive privileging of style over biology is in line with Evola’s views.

Hansen does not discuss Evola’s views on Negroes, to which Christophe Boutin devotes several pages of Politique et Tradition.[40] In his 1968 collection of essays, The Bow and the Club,[41] there is a chapter on “America Negrizzata,” which argues that, while there was relatively little miscegenation in the United States, the Telluric or Negro spirit has had considerable influence on the quality of American culture. The 1972 edition of Men Among the Ruins ends with an “Appendix on the Myths of our Time,” of which number IV is “Taboos of our Times.”[42] The two taboos discussed forbid a frank discussion of the “working class,” common in Europe, and of the Negro. Although written thirty years ago, it is up-to-date in its description of this subject and notices that the word “Negro” itself was becoming taboo as “offensive.”[43] La vera Destra, a real Right, will oppose this development. This appendix is not translated in the Inner Traditions or the 1991 German editions, confirming its accuracy.

At the end of Men Among the Ruins, instead of the Appendix of the 1972 edition, stands Evola’s 1951 Autodifesa, the speech he gave in his own defense when he was tried by the Italian democracy for “defending Fascism,” attempting to reconstitute the dissolved Fascist Party” and being the “master” and inspirer” of young Neo-Fascists.[44] Like Socrates, he was accused of not worshipping the gods of the democracy and of corrupting youth. When he asked in open court where in his published writings he had defended “ideas proper to Fascism,” the prosecutor, Dr. Sangiorgi, admitted that there were no such passages, but that the general spirit of his works promoted “ideas proper to Fascism,” such as monocracy, hierarchism, aristocracy or elitism. Evola responded.

I should say that if such are the terms of the accusation,[45] I would be honored to see, seated at the same bank of accusation, such people as Aristotle, Plato, the Dante of De Monarchia, and so on up to Metternich and Bismarck. In the same spirit as a Metternich, a Bismarck,[46] or the great Catholic philosophers of the principle of authority, De Maistre and Donoso Cortés, I reject all that which derives, directly or indirectly, from the French Revolution and which, in my opinion, has as its extreme consequence Bolshevism; to which I counterpose the ‘world of Tradition.’ . . . My principles are only those that, before the French Revolution, every well-born person considered sane and normal.[47]

Evola’s Autodifesa was more effective than Socrates’ Apology, since the jury found him “innocent” of the charges. (Italian juries may find a defendant “innocent,” “not guilty for lack of proof,” or “guilty.”) Evola noted in his speech, “Some like to depict Fascism as an ‘oblique tyranny.’[48] During that ‘tyranny’ I never had to undergo a situation like the present one.” Evola was no lackey of the Fascist regime. He attacked conciliation with the Vatican in the years before the 1929 Vatican Accords and developed an interpretation of race that directly contradicted the one favored by the German government and important currents within Fascism. His journal, La Torre (The Tower), was closed down in 1930 because of his criticism of Fascist toughs, gli squadristi. Evola, however, never had to face jail for his serious writings during the Fascist era. That had to wait for liberal democracy. Godwin and Hansen are absolutely correct to emphasize Evola’s consistency and coherence as an esoteric thinker and his independence from any party-line adherence to Fascism. On the other hand, Evola considered his politics a direct deduction from his beliefs about Tradition. He was a sympathetic critic of Fascism, but a remorseless opponent of liberal democracy.

Inner Traditions and the Holmes Publishing Group[49] have published translations of most of Evola’s esoteric writings and some important political books. Will they go on to publish the rest of his oeuvre? Joscelyn Godwin, after all, wrote, “It would be intellectually dishonest to suppress anything.” Evola’s book on Ernst Jünger might encourage a translation of Der Arbeiter. Riding the Tiger[50] explains how the “differentiated man” (uomo differenziato) can maintain his integrity in the Dark Age. It bears the same relation to Men Among the Ruins that Aristotle’s Ethics bears to his Politics and, although published later, was written at the same time.Riding the Tiger[51] There are brilliant essays in The Bow and the Club, but can a book be published in contemporary America with an essay entitled “America Negrizzata?” Pagan Imperialism is a young man’s book, vigorous and invigorating.

The most challenging book for readers who enjoy Men Among the Ruins is Fascism Seen from the Right, with its appendix, “Notes on the Third Reich,”Riding the Tiger[52] where Evola criticizes both regimes as not right-wing enough. A world respectful of communism and liberalism (and accustomed to using the word “Fascist” as an angry epithet) will find it hard to appreciate a book critical, but not disrespectful, of il Ventennio (the Twenty Years of Fascist rule). I would suggest beginning with the short pamphlet, Orientamenti (Orientations),[53] which Evola composed in 1950 as a summary of the doctrine of Men Among the Ruins.

Hansen quotes right-wing Italians who say that Evola’s influence discourages political action because his Tradition comes from an impossibly distant past and assumes an impossibly transcendent truth and a hopelessly pessimistic view of the present. Yet Evola confronts the modern world with an absolute challenge. Its materialism, egalitarianism, feminism, and economism are fundamentally wrong. The way out is through rejecting these mistakes and returning to spirit, transcendence and hierarchy, to the Männerbund and the Legionary Spirit. It may be discouraging to think that we are living in a Dark Age, but the Kali Yuga is also the end of a cosmic cycle. When the current age ends, a new one will begin. This is not Spengler’s biologistic vision, where our civilization is an individual, not linked to earlier ones and doomed to die without offspring, like all earlier ones.[54]

We are linked to the past by Tradition and when the Dark Age comes to an end, Tradition will light the way to new greatness and accomplishment. We may live to see that day. If not, what will survive is the legionary spirit Evola described in Orientamenti:

It is the attitude of a man who can choose the hardest road, fight even when he knows that the battle is materially lost and live up to the words of the ancient saga, ‘Loyalty is stronger than fire!’ Through him the traditional idea is asserted, that it is the sense of honor and of shame – not halfway measures drawn from middle class moralities – that creates a substantial, existential difference among beings, almost as great as between one race and another race. If anything positive can be accomplished today or tomorrow, it will not come from the skills of agitators and politicians, but from the natural prestige of men both of yesterday but also, and more so, from the new generation, who recognize what they can achieve and so vouch for their idea.[55]

This is the ideal of Oswald Spengler’s Roman soldier, who died at this post at Pompeii as the sky fell on him, because he had not been relieved. We do not need programs and marketing strategies, but men like that. “It is men, provided they are really men, who make and unmake history.”[56] Evola’s ideal continues to speak to the right person. “Keep your eye on just one thing: to remain on your feet in a world of ruins.”

End Notes

[1]. La dottrina del risveglio, Bari, 1943, revised in 1965.

[2]. Lo Yoga della potenza, Milan, 1949, revised in 1968, was a new edition of L’Uomo come Potenza, Rome, 1926; Metafisica del sesso, Rome, 1958, revised 1969.

[3]. Introduzione alla magia quale scienza del’Io, 3 volumes, Rome, 1927-29, revised 1971, Introduction to Magic: Rituals and Practical Techniques for the Magus, Rochester, VT: 2001; La tradizione hermetica (Bari, 1931), revised 1948, 1971; The Hermetic Tradition, Rochester, VT: 1995.

[4]. Rivolta contro il mondo moderno, Milan, 1934, revised 1951, 1969.

[5]. Robin Waterfield gives a useful bibliography at the end of his Gnosis essay (note 8, below) p. 17.

[6]. Karlheinz Weissman, “Bibliographie” in Menschen immitten von Ruinen, Tübingen, 1991, pp. 403-406, e.g., Heidnischer Imperialismus, Leipzig, 1933; Erhebung wider die moderne Welt, Stuttgart, 1935; Revolte gegen die moderne Welt, Berlin, 1982; Den Tiger Reiten, Vilsborg, 1997.

[7]. Thomas Sheehan, “Myth and Violence: The Fascism of Julius Evola and Alain de Benoist,” Social Research 48: 1981, pp. 45-73; Franco Ferraresi, “Julius Evola: tradition, reaction and the Radical Right,” Archives européennes de sociologie 28: 1987, pp. 107-151; Richard Drake, “Julius Evola and the Ideological Origins of the Radical Right in Contemporary Italy,” in Peter H. Merkl, (ed.), Political Violence and Terror: Motifs and Motivations, Berkeley, 1986, pp. 61-89; idem, The Revolutionary Mystique and Terrorism in Contemporary Italy, Bloomington, 1989.

[8]. Robin Waterfield, “Baron Julius Evola and the Hermetic Tradition,” Gnosis 14:1989-90, pp. 12-17.

[9]. Elémire Zolla, “The Evolution of Julius Evola’s Thought,” Gnosis 14: 1989-90, pp. 18-20.

[10]. Jay Kinney, “Who’s Afraid of the Bogeyman? The Phantasm of Esoteric Terrorism,” Gnosis 14: 1989-90, pp. 21-24.

[11].. Gli uomini e le rovine, Rome, 1953, revised 1967, with a new appendix, 1972.

[12]. H. T. Hansen, “Julius Evolas politisches Wirken,” Menshen immitten von Ruinen (note 6, above) pp. 7-131.

[13]. H. T. Hansen, “A Short Introduction to Julius Evola” in Revolt Against the Modern World, Rochester, VT, 1995, ix-xxii, translated from Hansen’s article in Theosophical History 5, January 1994, pp. 11-22.

[14]. Christophe Boutin, Politique et Tradition: Julius Evola dans le siècle, 1898-1974; Paris, 1992.

[15]. Il mistero del Graal e la tradizione ghibellina dell’Impero, Bari, 1937, revised 1962, 1972; translated as The Mystery of the Grail: Initiation and Magic in the Quest for the Spirit, Rochester, Vt., 1997.

[16]. René Guénon, Crise du monde moderne (Paris, 1927) has been translated several times into English.

[17]. H. T. Hansen, “Julius Evola und die deutsche konservative Revolution,” Criticón 158 (April/Mai/June 1998) pp. 16-32.

[18]. Diorema: Antologia della pagina special di “Regime Fascista,” Marco Tarchi, (ed.) Rome, 1974.

[19]. Lettere di Julius Evola a Carl Schmitt, 1951-1963, Rome, 2000.

[20]. L”Operaio” nel pensiero di Ernst Jünger (Rome, 1960), revised 1974; reprinted with additions, 1998.

[21]. The Concept of the Political, New Brunswick, NJ, 1976; The Crisis of Parliamentary Democracy, Cambridge, MA, 1985; Political Theology, Cambridge, MA, 1985; Political Romanticism, Cambridge, MA, 1986. Recent commentary includes Paul Gottfried, Carl Schmitt: Politics and Theory, New York, 1990; Gopal Balakrishnan, The Enemy: An Intellectual Portrait of Carl Schmitt, London, 2000.

[22]. Ernst Jünger, Der Arbeiter. Herrschaft und Gestalt, Hamburg, 1932, was translated into Italian in 1985.

[23]. Armin Mohler, Die konservative Revolution in Deutschland, 1918-1932, Stuttgart, 1950, revised and expanded in 1972, 1989, 1994, 1999.

[24]. Panajotis Kondylis, Conservativismus: Geschichtlicher Gehalt und Untergang, Stuttgart, 1986, devotes 553 pages to this theme.

[25]. My impression is that daimonìa dell’economia implies “demonic possession by the economy.” In Orientamenti (see note 53, below), Evola writes of “l’allucinazione e la daimonìa dell’economia,” “hallucination and demonic possession.”

[26]. Men Among the Ruins: Post-War Reflections of a Radical Traditionalist, Rochester, VT, 2002, p. 166. “Absurd and deplorable” is for assurdo peggiore, literally, “the worst absurdity;” circolo buio e chiuso “dark and small circle,” literally “dark and closed circle.” Chiuso is used in weather reports for “overcast.”

[27]. Evola applied for membership in the Fascist Party in 1939 in order to enlist in the army as an officer, but in vain for reasons discussed by Hansen (note 26, above) xiii. The application was found by Dana Lloyd Thomas, “Quando Evola du degradato,” Il Borghese, March 29, 1999, pp. 10-13. Evola mentioned this in an interview with Gianfranco De Turris, I’Italiano 11, September, 1971, which can be found in some reprints of L’Orientamenti, e.g., Catania, 1981, 33 (See note 53, below).

[28]. Evola cites Heinrich Schurtz, Altersklassen und Männerbünde: Eine Darstellung der Grundformen der Gesellschaft, Berlin, 1902; A. van Gennep, Les rites du passage, Paris, 1909; The Rites of Passage, Chicago, 1960.

[29]. Men Among the Ruins (note 26, above) pp. 210-211; Gli uomini e le rovine (note 11, above) pp. 15-151. “A ridiculous hybrid and illegitimate organization” translates questa ridicola associazione ibrida e bastarda.

[30]. Elémire Zolla gives the essentials about Reghini’s influence on Evola in his Gnosis essay (note 9, above).

[31]. Imperialismo Pagano, Rome, 1928, p. 40.

[32]. Richard Drake, “Julius Evola, Radical Fascism, and the Lateran Accords,” Catholic Historical Review 74, 1988, pp. 403-319; E. Christian Kopff. “Italian Fascism and the Roman Empire,” Classical Bulletin 76: 2000, pp. 109-115.

[33]. Yvon de Begnac, Taccuini Mussoliniani, Francesco Perfetti, (ed.), Bologna, 1990, p. 647.

[34]. “L’Equivoco del razzismo scientifico,” Vita Italiana 30, September 1942.

[35]. Sintesi di dottrina della razza, Milan, 1941; Grundrisse der faschistischen Rassenlehre, Berlin, 1943.

[36]. Sintesi di dottrina della razza (note 35, above) p. 35. Since Hansen (note 26, above) 71 uses the German translation (note 12, above) 90, the last sentence reads “Fascist racial doctrine (Die faschistischen Rassenlehre) therefore holds a purely biological view of race to be inadequate.”

[37]. Il mito del sangue: Genesi del razzismo, Rome, 1937, revised 1942.

[38]. Ludwig Ferdinand Clauss, Rasse und Seele. Eine Einführung in den Sinn der leiblichen Gestalt, Munich, 1937; Rasse ist Gestalt, Munich, 1937.

[39]. Renzo de Felice, The Jews in Fascist Italy: A History, New York, 2001, 378, translation of Storia degli Ebrei Italiani sotto il Fascismo, Turin, 1961, revised 1972, 1988, 1993. Evola is discussed on pp. 392-3.

[40]. Boutin (note 14, above) pp. 197-200.

[41]. L’Arco e la clava, Milan, 1968, revised 1971. The article is pp. 39-46 of the new edition, Rome, 1995.

[42]. Gli uomini e le rovine (note 11, above) Appendice sui miti del nostro tempo, pp. 255-282; Tabù dei nostri tempi, pp. 275-282.

[43]. Gli uomini e le rovine (note 11, above) p. 276: la tabuizzazione che porta fino ad evitare l’uso della designazione “negro,” per le sue implicazioni “offensive.”

[44]. J. Evola, Autodifesa (Quaderni di testi Evoliani, no. 2) (Rome, n.d.)

[45]. Banco degli accusati is what is called in England the “prisoner’s dock.”

[46]. At this point, according to Autodifesa (note 44, above) p. 4, Evola’s lawyer, Franceso Carnelutti, called out, “La polizia è andata in cerca anche di costoro.” (“The police have gone to look for them, too.”)

[47]. Men Among the Ruins (note 25, above) pp. 293-294; Autodifesa (note 44, above) pp. 10-11.

[48]. Bieca is literally “oblique,” but in this context means rather “grim, sinister.”

[49]. Holmes Publishing Group (Edwards, WA) has published shorter works by Evola edited by the Julius Evola Foundation in Rome, e.g. René Guénon: A Teacher for Modern Times; Taoism: The Magic of Mysticism; Zen: The Religion of the Samurai; The Path of Enlightenment in the Mithraic Mysteries.

[50]. Cavalcare la tigre, Rome, 1961, revised 1971.

[51]. Gianfranco de Turris, “Nota del Curatore,” Cavalcare la tigre , 5th edition: Rome, 1995, pp. 7-11.

[52]. Il Fascismo, Rome, 1964; Il Fascismo visto dalla Destra, con Note sul terzo Reich, Rome, 1970.

[53]. Orientamenti (Rome, 1951), with many reprints.

[54]. J. Evola, Spengler e “Il tramonto dell’Occidente” (Quaderni di testi Evoliani, no. 14) (Rome, 1981).

[55]. Orientamenti, (note [53]., above), p. 12; somewhat differently translated by Hansen (note 26, above) p. 101.

[56]. Orientamenti (note 53, above) p. 16. Hansen (note [26]., above) p. 93 translates “It is humans, as far as they are truly human, that make history or tear it down,” reflecting the German (note 12, above) p. 118: “Es sind die Menschen, sofern sie wahrhaft Menschen sind, die die Geschichte machen oder sie niederreissen.” The parallel sentence in Men Among the Ruins (note 11, above) p. 109: sono gli uomini, finché sono veramente tali, a fare o a disfare la storia, is translated by Stucco (note 26, above) p. 181: “It is men who make or undo history.” He omits finché sono veramente tali, but gets the meaning of uomini right.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg Decadentie, verval van beschaving, het houdt de mensheid – en in elk geval het bewuste, het denkende deel ervan – al eeuwen in de ban. Het klinkt banaal, maar net als mensen hebben culturen, beschavingen geen eeuwigheidsduur en voelt iedereen bijna met de elleboog aan wanneer wij ons in een opgaande fase of in een neergaande fase van onze beschaving bevinden. Decadentie is een niet eenduidig te vatten fenomeen, er werden ganse boekenkasten over volgeschreven : niet alleen zijn er verschillende vormen van decadentie en verval, economisch, cultureel, demografisch, militair en tenslotte politiek, maar de verschillende vormen kunnen elkaar versterken of de invloed van deze of gene vorm afzwakken. Twee vragen houden geïnteresseerden bezig :

Decadentie, verval van beschaving, het houdt de mensheid – en in elk geval het bewuste, het denkende deel ervan – al eeuwen in de ban. Het klinkt banaal, maar net als mensen hebben culturen, beschavingen geen eeuwigheidsduur en voelt iedereen bijna met de elleboog aan wanneer wij ons in een opgaande fase of in een neergaande fase van onze beschaving bevinden. Decadentie is een niet eenduidig te vatten fenomeen, er werden ganse boekenkasten over volgeschreven : niet alleen zijn er verschillende vormen van decadentie en verval, economisch, cultureel, demografisch, militair en tenslotte politiek, maar de verschillende vormen kunnen elkaar versterken of de invloed van deze of gene vorm afzwakken. Twee vragen houden geïnteresseerden bezig : 1926 L’uomo come potenza. I tantri nella loro metafisica e nei loro metodi di autorealizzazione magica.

1926 L’uomo come potenza. I tantri nella loro metafisica e nei loro metodi di autorealizzazione magica. De Spengleriaanse opvatting van de aristocratische cultuur is schatplichtig aan Nietzsche, Julius Evola had er al op gewezen, de Duitse filosoof van Der Untergang zal er nooit van loskomen : “Het ideaal van de mens als een prachtig roofdier en een onverwoestbaar heerser bleef het geloofspunt van Spengler, en referenties naar een spirituele cyclus blijven bij hem sporadisch, onvolmaakt en verminkt vanuit zijn protestantse vooroordelen. De aanbidding van de aarde en de devotie voor de klassen van knechten, de graafschappen en de kastelen, intimiteit van tradities en corporatieve gemeenschappen, de organisch georganiseerde staat, het allerhoogste recht toegekend aan het ras (niet in biologische zin begrepen, maar in de zin van gedrag, van diep ingewortelde viriliteit), dit alles is het fundament van Spengler, waarin volkeren zich in de fase van de cultuur ontwikkelen. Maar eigenlijk is dit alles te weinig… In de loop van de geschiedenis is een dergelijke wereld eerder te vinden reeds als het gevolg van een eerste val. We bevinden ons dan in de cyclus van de “krijgersmaatschappij”, het traditionele tijdperk dat vorm krijgt eens het contact met de transcendente realiteit verbroken werd, en die ophoudt de creatieve kracht van de beschaving te zijn” (39). Oswald Spengler gaat dus in de eerste plaats niet ver genoeg in zijn analyses, en verder haalt hij ook niet de juiste referenties aan. Daarom, schrijft Julius Evola op pagina 11, “komt Spengler ons eerder voor als de epigoon van het conservatisme, van het beste traditionele Europa, die haar ondergang bezegeld zag in de Eerste Wereldoorlog en het ineenstorten van de laatste Europese rijken”.

De Spengleriaanse opvatting van de aristocratische cultuur is schatplichtig aan Nietzsche, Julius Evola had er al op gewezen, de Duitse filosoof van Der Untergang zal er nooit van loskomen : “Het ideaal van de mens als een prachtig roofdier en een onverwoestbaar heerser bleef het geloofspunt van Spengler, en referenties naar een spirituele cyclus blijven bij hem sporadisch, onvolmaakt en verminkt vanuit zijn protestantse vooroordelen. De aanbidding van de aarde en de devotie voor de klassen van knechten, de graafschappen en de kastelen, intimiteit van tradities en corporatieve gemeenschappen, de organisch georganiseerde staat, het allerhoogste recht toegekend aan het ras (niet in biologische zin begrepen, maar in de zin van gedrag, van diep ingewortelde viriliteit), dit alles is het fundament van Spengler, waarin volkeren zich in de fase van de cultuur ontwikkelen. Maar eigenlijk is dit alles te weinig… In de loop van de geschiedenis is een dergelijke wereld eerder te vinden reeds als het gevolg van een eerste val. We bevinden ons dan in de cyclus van de “krijgersmaatschappij”, het traditionele tijdperk dat vorm krijgt eens het contact met de transcendente realiteit verbroken werd, en die ophoudt de creatieve kracht van de beschaving te zijn” (39). Oswald Spengler gaat dus in de eerste plaats niet ver genoeg in zijn analyses, en verder haalt hij ook niet de juiste referenties aan. Daarom, schrijft Julius Evola op pagina 11, “komt Spengler ons eerder voor als de epigoon van het conservatisme, van het beste traditionele Europa, die haar ondergang bezegeld zag in de Eerste Wereldoorlog en het ineenstorten van de laatste Europese rijken”.

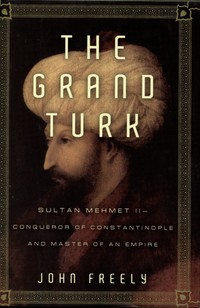

Sultan Mehmet II, the Grand Turk, known to his countrymen as Fatih, 'the Conqueror', and to much of Europe as 'the present Terror of the World', was once the most feared and powerful ruler in the world. The seventh of his line to rule the Ottoman Turks, Mehmet was barely 21 when he conquered Byzantine Constantinople, which became Istanbul and the capital of his mighty empire. Mehmet reigned for 30 years, during which time his armies extended the borders of his empire halfway across Asia Minor and as far into Europe as Hungary and Italy. Three popes called for crusades against him as Christian Europe came face to face with a new Muslim empire.Mehmet himself was an enigmatic figure. Revered by the Turks and seen as a cruel and brutal tyrant by the west, he was a brilliant military leader but also a renaissance prince who had in his court Persian and Turkish poets, Arab and Greek astronomers and Italian scholars and artists. In this, the first biography of Mehmet for 30 years, John Freely vividly brings to life the world in which Mehmet lived and illuminates the man behind the myths, a figure who dominated both East and West from his palace above the Golden Horn and the Bosphorus, where an inscription still hails him as, 'Sultan of the two seas, shadow of God in the two worlds, God's servant between the two horizons, hero of the water and the land, conqueror of the stronghold of Constantinople."

Sultan Mehmet II, the Grand Turk, known to his countrymen as Fatih, 'the Conqueror', and to much of Europe as 'the present Terror of the World', was once the most feared and powerful ruler in the world. The seventh of his line to rule the Ottoman Turks, Mehmet was barely 21 when he conquered Byzantine Constantinople, which became Istanbul and the capital of his mighty empire. Mehmet reigned for 30 years, during which time his armies extended the borders of his empire halfway across Asia Minor and as far into Europe as Hungary and Italy. Three popes called for crusades against him as Christian Europe came face to face with a new Muslim empire.Mehmet himself was an enigmatic figure. Revered by the Turks and seen as a cruel and brutal tyrant by the west, he was a brilliant military leader but also a renaissance prince who had in his court Persian and Turkish poets, Arab and Greek astronomers and Italian scholars and artists. In this, the first biography of Mehmet for 30 years, John Freely vividly brings to life the world in which Mehmet lived and illuminates the man behind the myths, a figure who dominated both East and West from his palace above the Golden Horn and the Bosphorus, where an inscription still hails him as, 'Sultan of the two seas, shadow of God in the two worlds, God's servant between the two horizons, hero of the water and the land, conqueror of the stronghold of Constantinople." Voor wie professor Tommissen niet zou kennen, hij gaat de wereld rond als dé Carl Schmitt-kenner bij uitstek, die gans Europa ons trouwens benijdt. Derhalve kunnen we niet om de vaststelling heen dat zowat elke grote natie zijn Schmitt-renaissance heeft gekend, met uitzondering van dit dwergenlandje België. Terwijl juist hier…inderdaad!

Voor wie professor Tommissen niet zou kennen, hij gaat de wereld rond als dé Carl Schmitt-kenner bij uitstek, die gans Europa ons trouwens benijdt. Derhalve kunnen we niet om de vaststelling heen dat zowat elke grote natie zijn Schmitt-renaissance heeft gekend, met uitzondering van dit dwergenlandje België. Terwijl juist hier…inderdaad! No sólo sus primeras lecturas lo acercan a los autores galos del siglo XVIII, sino también sus estudios universitarios los desarrolló en las universidades más progresistas y, por ende, más afrancesadas de la España de entonces.

No sólo sus primeras lecturas lo acercan a los autores galos del siglo XVIII, sino también sus estudios universitarios los desarrolló en las universidades más progresistas y, por ende, más afrancesadas de la España de entonces. Liliput-Roboter

Liliput-Roboter Les prolégomènes de l'attaque allemande contre l'URSS (22 juin 1941)

Les prolégomènes de l'attaque allemande contre l'URSS (22 juin 1941) El líder venezolano dio instrucciones a su gobierno de acelerar la realización del proyecto sobre la construcción por las compañías rusas del complejo de centrales termoeléctricas que funcionan a base de coque de petróleo. El ministro de Energía y Petróleo de Venezuela Rafael Ramírez llegará pronto a Moscú y discutirá este problema con sus colegas rusos.

El líder venezolano dio instrucciones a su gobierno de acelerar la realización del proyecto sobre la construcción por las compañías rusas del complejo de centrales termoeléctricas que funcionan a base de coque de petróleo. El ministro de Energía y Petróleo de Venezuela Rafael Ramírez llegará pronto a Moscú y discutirá este problema con sus colegas rusos. Ex:

Ex: Wessen Gegner?

Wessen Gegner? Pour en finir avec l'hitléromanie

Pour en finir avec l'hitléromanie

La liste des centres de recherche asiatiques suivante vise à fournir des indications sur l'état de la pensée stratégique dans la région et l'organisation de la recherche dans le domaine. L'énumération n'est pas exhaustive.

La liste des centres de recherche asiatiques suivante vise à fournir des indications sur l'état de la pensée stratégique dans la région et l'organisation de la recherche dans le domaine. L'énumération n'est pas exhaustive. Delhi Policy Group (DPG)

Delhi Policy Group (DPG) National Institute for Research Advancement (NIRA)

National Institute for Research Advancement (NIRA) Principale publication (en anglais))

Principale publication (en anglais)) Sarà una guerra diversa quella che l’amministrazione Obama ha intenzione di condurre contro il terrorismo e i nemici degli Stati Uniti. Non certo meno costosa - visto che il piano spese presentato in questi giorni dal presidente è solo lievemente inferiore a quelli presentati negli ultimi due anni del suo predecessore - ma sicuramente diversa da quella di Bush. La nuova strategia messa a punto dal ministro della Difesa Robert Gates, infatti, punta soprattutto sull’aumento delle operazioni speciali segrete, sull’utilizzo massiccio degli aerei senza pilota e su una rinnovata attenzione nei confronti degli Stati “deboli”, come Yemen e Somalia, considerati un rifugio sicuro per gli uomini di Al Qaida. In generale, Gates ha sottolineato la necessità di abbandonare la precedente politica (eredità della Guerra Fredda), che chiedeva alle forze armate di prepararsi a combattere simultaneamente in due conflitti regionali (ad esempio in Vicino Oriente e nella penisola coreana), e di sostituirla con la capacità di fronteggiare diversi conflitti minori in ogni parte del mondo. Le linee guida di questo riordino sono descritte nel Quadriennal Defense Review (QDR), il rapporto quadriennale del Pentagono presentato lunedì scorso. Il testo indica come priorità attuale delle forze armate statunitensi il “prevalere nelle guerre odierne“ e sostiene la necessità di “smantellare le reti terroristiche” in Afghanistan e in Iraq.

Sarà una guerra diversa quella che l’amministrazione Obama ha intenzione di condurre contro il terrorismo e i nemici degli Stati Uniti. Non certo meno costosa - visto che il piano spese presentato in questi giorni dal presidente è solo lievemente inferiore a quelli presentati negli ultimi due anni del suo predecessore - ma sicuramente diversa da quella di Bush. La nuova strategia messa a punto dal ministro della Difesa Robert Gates, infatti, punta soprattutto sull’aumento delle operazioni speciali segrete, sull’utilizzo massiccio degli aerei senza pilota e su una rinnovata attenzione nei confronti degli Stati “deboli”, come Yemen e Somalia, considerati un rifugio sicuro per gli uomini di Al Qaida. In generale, Gates ha sottolineato la necessità di abbandonare la precedente politica (eredità della Guerra Fredda), che chiedeva alle forze armate di prepararsi a combattere simultaneamente in due conflitti regionali (ad esempio in Vicino Oriente e nella penisola coreana), e di sostituirla con la capacità di fronteggiare diversi conflitti minori in ogni parte del mondo. Le linee guida di questo riordino sono descritte nel Quadriennal Defense Review (QDR), il rapporto quadriennale del Pentagono presentato lunedì scorso. Il testo indica come priorità attuale delle forze armate statunitensi il “prevalere nelle guerre odierne“ e sostiene la necessità di “smantellare le reti terroristiche” in Afghanistan e in Iraq. Jean de Maillard, 58 ans, vice-président au tribunal de grande instance d’Orléans, s’intéresse aux mutations économiques, financières et sociales nées de la mondialisation. Dans « Le Rapport censuré » (Flammarion), publié en 2004, il a repris un travail « trappé » sur les menaces engendrées par les circuits de l’argent sale, réalisé pour le ministère des Affaires étrangères.

Jean de Maillard, 58 ans, vice-président au tribunal de grande instance d’Orléans, s’intéresse aux mutations économiques, financières et sociales nées de la mondialisation. Dans « Le Rapport censuré » (Flammarion), publié en 2004, il a repris un travail « trappé » sur les menaces engendrées par les circuits de l’argent sale, réalisé pour le ministère des Affaires étrangères. Survival

Survival Archives de SYNERGIES EUROPEENNES - 1979

Archives de SYNERGIES EUROPEENNES - 1979 Sombart, opposant la mentalité aristocratique à l'esprit "bourgeois proprement dit" (c'est-à-dire dénué de la composante de l'esprit d'entreprise), note: "Les uns chantent et résonnent, les autres n'ont aucune résonnance; les uns sont resplendissants de couleurs, les autres totalement incolores. Et cette opposition s'applique non seulement aux deux tempéraments comme tels, mais aussi à chacune des manifestations de l'un et de l'autre. Les uns sont artistes (par leur prédispositions, mais non nécessairement par leur profession), les autres fonctionnaires, les uns sont faits de soie, les autres de laine". Ces traits de "bourgeoisime" ne caractérisent plus aujourd'hui une classe (car il n'y a plus de classe bourgeoise) mais la société toute entière. Nous vivons à l'ère du consensus bourgeois.

Sombart, opposant la mentalité aristocratique à l'esprit "bourgeois proprement dit" (c'est-à-dire dénué de la composante de l'esprit d'entreprise), note: "Les uns chantent et résonnent, les autres n'ont aucune résonnance; les uns sont resplendissants de couleurs, les autres totalement incolores. Et cette opposition s'applique non seulement aux deux tempéraments comme tels, mais aussi à chacune des manifestations de l'un et de l'autre. Les uns sont artistes (par leur prédispositions, mais non nécessairement par leur profession), les autres fonctionnaires, les uns sont faits de soie, les autres de laine". Ces traits de "bourgeoisime" ne caractérisent plus aujourd'hui une classe (car il n'y a plus de classe bourgeoise) mais la société toute entière. Nous vivons à l'ère du consensus bourgeois.

Men zou dus denken dat de voorstellen van politici voor een ééngemaakte politiezone Brussel, nu heeft elke burgemeester zowat zijn eigen politiemacht, en een zerotolerantie op algemene consensus wordt onthaald. Dit is wel en niet het geval. Langs Vlaamse kant zijn alle partijen het eens dat dit moet gebeuren, van Groen! t.e.m. het Vlaams Belang. Maar, afgaande ook op de berichtgeving in het avondjournaal op Één, is dit langs Franstalige kant zeker niet het geval. Daar worden de voorstellen tot hervorming bekeken als “Vlaamse eisen” en “extreem-rechtse” praat.

Men zou dus denken dat de voorstellen van politici voor een ééngemaakte politiezone Brussel, nu heeft elke burgemeester zowat zijn eigen politiemacht, en een zerotolerantie op algemene consensus wordt onthaald. Dit is wel en niet het geval. Langs Vlaamse kant zijn alle partijen het eens dat dit moet gebeuren, van Groen! t.e.m. het Vlaams Belang. Maar, afgaande ook op de berichtgeving in het avondjournaal op Één, is dit langs Franstalige kant zeker niet het geval. Daar worden de voorstellen tot hervorming bekeken als “Vlaamse eisen” en “extreem-rechtse” praat. Het gaat daar dus ondertussen zo ver dat men, puur uit koppigheid en oogkleppenmentaliteit, regelrecht weigert om maatregelen te nemen. Die ideeën komen immers uit Vlaamse hoek en het Vlaams Belang heeft die ideeën ook geuit. Dat is zoals verkiezen om te verdrinken omdat de persoon die je wilt komen redden een andere maatschappijvisie heeft. In Terzake van 1 februari 2010 konden we ook nog vernemen dat deze overvallen, volgens

Het gaat daar dus ondertussen zo ver dat men, puur uit koppigheid en oogkleppenmentaliteit, regelrecht weigert om maatregelen te nemen. Die ideeën komen immers uit Vlaamse hoek en het Vlaams Belang heeft die ideeën ook geuit. Dat is zoals verkiezen om te verdrinken omdat de persoon die je wilt komen redden een andere maatschappijvisie heeft. In Terzake van 1 februari 2010 konden we ook nog vernemen dat deze overvallen, volgens

Karlheinz Weissmann:

Karlheinz Weissmann: Archives de SYNERGIES EUROPEENNES - 1985

Archives de SYNERGIES EUROPEENNES - 1985 Burgess critique également la division du monde en trois blocs ou zones de puissance qui apparaît dans le 1984 d'Orwell. Il déclare cette vision irréaliste. Pour les lecteurs de Vouloir et Orientations habitués à l'argumentation géopolitique, bornons-nous à constater, ici, que George Orwell imaginait, à l'aube des années 50, qu'une superpuissance eurasiatique (le bloc imaginé par Haushofer, Niekisch et les signataires du Pacte germano-soviétique d'août 1939) allait se constituer pour défier le Nouveau Monde et l'Océania thalassocratique, c'est-à-dire les États-Unis avec leur arrière-cour sud-américaine et le Commonwealth.

Burgess critique également la division du monde en trois blocs ou zones de puissance qui apparaît dans le 1984 d'Orwell. Il déclare cette vision irréaliste. Pour les lecteurs de Vouloir et Orientations habitués à l'argumentation géopolitique, bornons-nous à constater, ici, que George Orwell imaginait, à l'aube des années 50, qu'une superpuissance eurasiatique (le bloc imaginé par Haushofer, Niekisch et les signataires du Pacte germano-soviétique d'août 1939) allait se constituer pour défier le Nouveau Monde et l'Océania thalassocratique, c'est-à-dire les États-Unis avec leur arrière-cour sud-américaine et le Commonwealth.