Bourgeois bodies exist only within a matrix of consumption, so much so that even “healthy lifestyles” are merely another marketing niche to be utilized by demographically defined individuals seeking more self-expression and corporate-friendly individuality. Health, as bourgeois capitalist science understands it, is most useful as a way of prolonging a life of consumption. This is clear when even radical scientists (such as New Biology advocate Bruce Lipton) advise their audiences to use health as a way to live “happier and longer.” Comfort, peace, security, and the prolonging of life are there for the taking – so long as the dystopia that makes health and fitness marketable to begin with is ignored.

But, these same arguments of bodily manipulation may be read as the promise of a foundation upon which a new cultural and physiological reality may develop. If we become soft and weak under the manacles of bourgeois modernity, might we also become hard and strong by the counter-narratives being created at the extreme edges of modernity? If bourgeois scientists tell us that we may counter the effects of modernity with even more softness, ecumenicalism, and “love,” they do so only because of a prohibition against bodily violence, hierarchy, and discrimination; and to direct the body even further away from its natural inclinations.

But does the body need violence, hierarchy, and discrimination? What is it about the naturalness of the body that is so dangerous? If softness and “free love” encourage one avenue of manipulation, what might become of us if harshness, precision, strictness, and a reimagining of our heroic past became our ideals? What might happen if, in all this talk about the body and physiology, there was a way to better understand the problems of morality and bourgeois selfhood? It is the purpose of this paper to address these questions while examining Friedrich Nietzsche’s understanding of physiology and the consequences of vitality.

Physiology versus Metaphysics

From his earliest notebooks and teaching materials in the 1870s to his last discernable thoughts in the 1880s, Friedrich Nietzsche was convinced that the body was the key to all of the causes of modern man’s cultural and intellectual degeneration. This was due in large part to the Christian and scientific separation of mind/soul and body, which not only made an abstraction of the body in order to convince men of their own divinity, but also, more importantly, encouraged them to ignore the bodily origins – and bodily connections – of what the church and scientists assumed made them divine. Against the modern metaphysical explanations of the “burden of man,” Nietzsche followed the Greeks and proposed instead the “nature” of man’s existence.

Nietzsche wrote so much on physiology that it is difficult to find a definitive statement or ideal on the subject. As we will see, Nietzschean physiology is primarily a way of reuniting the body and soul of the Greek ideal. Yet, it was not merely a metaphorical tool, for Nietzsche was deeply concerned that modern men were unable to understand their place in the world because of their inability to understand physiology. For the body, its instincts, and general functions was the source of consciousness, the will, and reason. Its vitality was, thus, directly related to the contours and functioning of all communicable human experience.

Through a complex web of signification, education, and communication, the body was also the source of morality and political philosophy. The body, and how humans come to care for, treat, ignore, or worship it, says much to Nietzsche about the ideals and supraordinate goals of a form of life. Later, we will examine how ascendant and descendant forms of life understand and use the body. First, however, we begin with a rough chronology of Nietzsche’s physiological philosophy.

In 1871, Nietzsche taught a course on Greek rhetoric that allowed the young professor to discuss at great length the power of persuasion in a world knowable only through interpretation. This epistemological approach put him at odds with the more established faculty members who sought metaphysical certainty over metaphorical mystification. However, far from stopping at an epistemological demolition of truth and reality, Nietzsche grounded epistemology itself in physiology, arguing that bodily processes limit and direct grammar, logic, and causality – the underlying principles through which we know the world.[2]

In a notebook entry from the same period, Nietzsche toyed with the notion that art is a manifestation of instincts making themselves known through consciousness. He posited that ideals, as well, have instinctual and thus bodily origins.[3] A few years later, in his “middle period,” Nietzsche more confidently discussed physiology and instincts, arguing that the intellect itself is only the symptom and instrument of “a bodily drive.”[4] This was part of a general argument that defined this period of his thought.[5] Whereas his earliest works can be said to organize around the conflict between science, art, and philosophy (and the concomitant divergence of truth and beauty), the middle period trilogy[6] is built upon Nietzsche’s use of physiology as a way to move beyond metaphysics.

This movement beyond metaphysics was a two-fold process. The first involved Nietzsche’s own study of physiology. Christian Emden makes a persuasive case that Nietzsche came to regard physiology so highly as a result of his own suffering. Wracked with headaches, nausea, and poor vision throughout his teaching tenure in Basel, Nietzsche poured through the scientific literature of the day, seeking diagnostic and curative possibilities. His notebooks indicate that he was particularly impressed with the ideas of Friedrich Albert Lange, a prominent philosopher of materialism who studied the physiology of sensory perception. Lange suggested that mental states such as thinking or feeling were the result of physiological functions occurring at the conceptual and preconceptual level. He was particularly interested in the physiology of thought, which he studied metaphorically through an examination of the mechanics of speech. His work theorized that thought is subject to constantly fluctuating bodily stimulation.[7]

As for Nietzsche himself, the two volumes of Human, All Too Human were written as an act of war against the physical pain of his everyday life. Gary Handwerk explains that this pain led to Nietzsche’s new aphoristic style and identity as a critic of Schopenhauer’s pessimism. His self-transformation was a question of mood and tone, and bespoke of a style that hit hard, fast, and precise. But Nietzsche knew that his style was also a direct reflection of his physiological state, and, importantly, he began to assume that such was the case for all philosophers. What made Nietzsche’s new style so martial (in regards to its subject matter), though, was his rejection of pessimism, for he had become determined to embrace a love of life that especially included and celebrated its darkest moments.[8] Nietzsche got no “enlightenment” from suffering, apart from realizing that it is an everyday part of life. As such, he believed – much to the chagrin of Christian priests and modern progressives – that suffering must combine with joy to teach us who we are, and that, to deny the one for the sake of the other was to commit an act of cowardice in the very face of life.

The second process involved making this type of “physiological knowledge” the basis of many human experiences assumed by religion, science, and philosophy to come from a metaphysical source. To do so, he turned to the instincts, specifically theorizing the origins, content, and purposiveness of this much-maligned mystery of the body. Like Lange, he saw the instincts as a product of physiological drives. But unlike Lange, he was convinced that the body’s instinctual processes produced consciousness, renaturalizing one of the pillars of metaphysics. He even began thinking about the impact of digestion on conceptualization. In the meantime, however, he realized that transvalued instincts gave him a way around the Christian/Platonic belief that exalting the human means to move beyond our animalistic drives.[9]

Having descended from a long line of Protestant preachers, Nietzsche undoubtedly knew, but still studied, the many methods of flesh-desecration promoted by Christianity to save the soul from bodily temptation.[10] He began to see the healthy body as a weapon against a Christianity that stimulated sickness as a means of salvation. But why did it do so? Later, Nietzsche answers the question in a number of ways that point to the political reality of the early church, as well as the nature of the first Christians.

In “The Religious Life” in Human, All Too Human, he follows the latter path to a scathing conclusion: “the saint” is the product of “a sick nature . . . spiritual poverty, faulty knowledge, ruined health, and overexcited nerves.”[11] In other words, the saint is the product of his derelict body and impoverished instincts, and not some metaphysical deity or utopia; just as all behaviors and concepts can be related to the physiological state of their human bearers. This type of analysis served Nietzsche well in his later examinations of the origins of morality. It demonstrates that physiology was not merely a metaphorical platform for explaining human behavior, but in fact, a philoso-scientific way of naturalizing even the most exalted of ethico-behavioral schemes.

In “The Religious Life” in Human, All Too Human, he follows the latter path to a scathing conclusion: “the saint” is the product of “a sick nature . . . spiritual poverty, faulty knowledge, ruined health, and overexcited nerves.”[11] In other words, the saint is the product of his derelict body and impoverished instincts, and not some metaphysical deity or utopia; just as all behaviors and concepts can be related to the physiological state of their human bearers. This type of analysis served Nietzsche well in his later examinations of the origins of morality. It demonstrates that physiology was not merely a metaphorical platform for explaining human behavior, but in fact, a philoso-scientific way of naturalizing even the most exalted of ethico-behavioral schemes.

Nietzsche maintained this line of thought until the end of his conscious life, making the body a veritable warzone, but one that could be used creatively and artistically against the regimes of metaphysical truth proposed by priests, scientists, and philosophers.[12]

Zarathustra Contra Darwin

In the two years between Dawn and the publication of Thus Spoke Zarathustra, Nietzsche’s health stabilized, allowing him the failed romance with Lou Salomè, and, more importantly, a new perspective on “physiological knowledge” as a critique of the bourgeois Last Man. In Ecce Homo, Nietzsche looked back at this period’s superabundant health and its impact on his thought. Whereas illness had made him a “decadent,”[13] his great health made him instead “the opposite of a decadent.”[14] Thus, he had been blessed with the ability to clearly identify with two divergent human potentialities.

Being decadent, Nietzsche says, gave him a dialectician’s skill for searching out nuances in the most obscure spaces – searching for truth with abandon. But, as one bestowed with greater health, he came to understand that truth (and the search for truth) is a symptom of instinctual and physiological decline (he also explained the value of truth in its relation to certain humans’ need for security). In other words, Nietzsche “recognized how perspectives on life reflected the instinctual circumstances of individual wills.”[15] The clever beginning of Ecce Homo also reveals an important aspect of Nietzsche’s later thought on physiology: that great health and vitality are beyond truth – an idea that he explored in Zarathustra.

Along with eternal recurrence, the Übermensch is one of the two major concepts introduced in Thus Spoke Zarathustra.[16] Philosophically speaking, the Übermensch is the attainment of a complete transvaluation of decadent values, while, from the perspective of physiology, it is the overcoming of the Darwinian Last Man. And, looked at from Nietzsche’s perspective, it is the overcoming of the one through the attainment of the other.

Zarathustra explains that the Übermensch is not the fulfillment of a higher reason, but a higher body, for the body is the “seat of life.” Its energy is ultimately and purely “creative,” and as such, it created the spirit and the will.[17] But these manifestations of bodily energy – primal but unique to each body – are capable of being consciously disciplined, making transvaluation, as we shall see, a project that “starts at home.” Nietzsche means for the Übermensch to be a profoundly physical man, in whom the instincts and drives are coordinated, allowing active energy to guide all thought and action. This is energy, then, that is never reactive but indicative of the harmonious and propulsive will. Nietzsche sheds some light on this human type in his self-description at the beginning of Ecce Homo. In Nietzsche’s words, the Übermensch has “turned out well”:

He is cut from wood that is simultaneously hard, gentle, and fragrant. He only has a taste for what agrees with him . . . what does not kill him makes him stronger. He instinctively gathers his totality from everything he sees, hears, and experiences: he is a principle of selection; he lets many things fall by the wayside.[18]

The Übermensch is the literal embodiment of a superior state of being and a higher awareness that emerges from the harmony of instincts and the willful practice of self-selection and self-hygiene. His will makes all interaction with the world a benefit to himself, even going so far as to court risk, danger, and the possibility of death with the maximum of self-affirmation.[19] In other words, he does not seek or cherish objective survival (random Darwinian fitness)[20] but the pure expression of his will, regardless of the environment.

The Übermensch, though, is a singular phenomenon and not the goal of a common evolution. It is a transvaluation of the “most contemptible” subject of Darwinian evolution – itself the subject of the fifth part of “Zarathustra’s Prologue.”[21] In contrast to the Übermensch, the Last Man suffers from life, avoiding danger, and seeking comfort, base personal gratification, and individual survival; all the while hoping for a long and uneventful life.[22] By following this course, the bourgeois Last Man guarantees his type’s survival. He is “ineradicable, like the flea beetle.”[23] While a Darwinian might rejoice at the fecundity and self-preservation instinct of the Last Man, these only add up to a horribly mediocre human overrunning the earth.

The power, and perhaps confusing nature, of Zarathustra is that it perfectly summarizes vast stretches of Nietzsche’s complex thoughts on art, science, philosophy, physiology, morality, and politics in single sentences. Thus, as Zarathustra explains the internal features of the Last Man, he also explains the external influences and consequences of his behavioral instincts. These influences and consequences seem to revolve around softness. As we know, Nietzsche understands modernity primarily as an ethico-political system based in weakness. Zarathustra tells us that man is growing “smaller,” “modest,” “tame,” “cowardly,” “virtuous,” “mediocre,” and, among a host of other things, clever fingers “that do not know how to form fists.”[24]

In contrast to these traits and virtues, Zarathustra presents a short but dynamic model of the benefits of harshness.

You are becoming smaller and smaller, you small people! You are crumbling, you contented ones! You will yet perish of your many small virtues, of your many small abstentions, of your many small resignations! Too sparing, too yielding – that is your soil! But in order for a tree to grow tall, it needs to put down hard roots amid hard rock! And even what you abstain from weaves at the web of all future humanity.[25]

After Zarathustra connects strength’s need of resistance with “self-love” and the very ability to “will,” he returns to the implications of softness for the future by shifting the focus of the discourse squarely on modernity. He does so in two words: “poor soil.”[26] Poor soil, as he puts it, only grows poor weeds. Modernity, in other words, is only capable of producing inferior human types.

The Last Man survives not on account of any superiority – genetic or ethical – but because he lacks the sufficient energy and higher will to squander himself in pursuit of creative self-affirmation. He considers his survival a virtue rather than a direct expression of his instinctual reality – much like the priests who impose ascetic practices on the strong. The superiority of the Übermensch – over both the bourgeois Last Man and the priests – is ultimately physiological.

The Body and the Priest

Moving toward the late-1880s, it becomes ever more clear that the ethical and political implications of Nietzsche’s thought are visible in his naturalistic, life-affirming physiology. Although as in his earlier works, Nietzsche weaves in and out of the body and the environment, making decadence both a cause and effect of bodily and instinctual weakness, in his later works he focuses more on the political implications of decadence. Still, though, the body and the will are ever-present, as Nietzsche’s life-affirming philosophy demands (of itself and adherents) contest with temporal sources of weakness. Fostering a noble, affirmative type and challenging modernity are inseparable pieces of Nietzsche’s project; as life involves contest, the path to a noble life demands that one challenge the reactive and decadent forces in life.[27]

Nietzsche variously describes these decadent forces as those promoting democratization; exalting of compassion, weakness, and pity; and stimulating a cult of facility and painlessness, in order to make of Europeans a race of sheep-like herd animals.[28] The Übermensch becomes a historical actor because of his transvaluation of these forces. His enemies, likewise, are defined by their unmooring of these forces from their instinctual origins in physiological weakness, illness, and fatigue of life to become, instead, the metaphysical basis of a “good life.” As Nietzsche moved away from Zarathustra and the Last Man, he renewed his focus of attack on the priests. But in doing so, the archetype of decadence remained.

As Nietzsche makes clear in On the Genealogy of Morality, ascetic interpretation is the key to the priest’s struggle for earthly power. He promotes a denatured existence where all active, life-affirming forms of life are discredited. Over and above active, affirmative understandings of nature, the priests become purveyors of a “higher existence.”[29] But, in order to promote such a form of life, the priests must have been considered degenerates by the other – more powerful – castes to begin with.

This priestly subversion of nature is Nietzsche’s best proof that, contrary to Darwin, the weak do not perish of the “struggle for existence,” but in fact thrive in its face. Even if the priests are unable to participate in the natural, superabundant, active existence of the warriors, for example, they continue to cling to life through devotion to asceticism (and denial of the primacy of the body). For Nietzsche, though, this is only the beginning of the problem, as the ascetic practices do not give the priests physiological strength and health, but instead make them more sickly and debilitated. Removed thus from nature, the priests seek a form of self-mastery that promises revenge against life.[30]

Nietzsche not only sees in this proof that priestly metaphysics is an outgrowth of physiological degradation, but that Judeo-Christian morality cannot be understood without realizing the bodily origins of resentment. General morality exists in this scheme as the outcome of the human struggle for existence and the outgrowth of conflicting physiological drives. Morality reflects a constellation of emotions, instincts, and drives peculiar to specific (ascending or descending) human types. As Johnson explains, Nietzsche is not interested in locating morality in nature, but in revealing what moral interpretations tell us about human instinctual reality.[31]

Self-Overcoming and Politics

It is in the face of this transcendentalized decadence and resentment that the Übermensch or the “higher type” must act. But because of the transcendental nature of this decadence, the man who fights to destroy it must start first with destroying its vestiges in himself. This is why the Greek ideal – with its balanced and harmonious relationship between the body and the regulatory instincts – remained central to Nietzsche’s political philosophy. Against the anti-nature of the priests, the higher type must embrace the “evil” instincts – all of the active, dangerous, harsh, spontaneous, outer-directed impulses that Judeo-Christian modernity has condemned.

Doing so is the first step away from modernity and toward self-overcoming. The latter, though, is most important here, as Nietzsche displays in the memorable scene in which Zarathustra encounters the shepherd and the snake. Because man is not able to simply go back to periods of strength, will, and natural nobility, he must create of himself a person with character worthy of such a past. It is only through this self-overcoming that we will overcome modernity and the modern Last Man.

The contrast between the Übermensch, Last Man, and the priests – and the instinctual-behavioral distance that separates them – provides a solid foundation on which to build a discussion of Nietzsche’s physiological politics. For each of these human types, we not only have a struggle for mastery between ascendant and descendant instinctual processes, but also an ethico-political environment that reflects this struggle. Again, it is this fluidity between internal and external that demonstrates Nietzsche’s commitment to the Greek ideal as a potential post-modern political reality. It also reveals each unique individual’s path toward self-and-modern-overcoming.

Nietzsche’s last works and notebooks of 1888 focus on ascendant and descendant lines of human development. While these lines are not teleological, he believes, first, that they can be demonstrated historically and physiologically, and second, that each person embodies one of these two lines. As he states in Twilight of the Idols,

Selfishness is worth only as much as the physiological value of the selfish person: it can be worth a lot or it can be worthless and despicable. Individuals can be seen as representing either the ascending or descending line of life . . . If they represent the ascending line, then they have extraordinary value, – and since the whole of life advances through them, the effort put into their maintenance . . . might even be extreme.[32]

Nietzsche then combines this eugenic political suggestion with an extreme evolutionary statement, which puts the onus of history squarely on the individual even as it is being decentered.

Individuals are nothing in themselves, they are not atoms, not ‘links in the chain.’ They are not just legacies of a bygone era, – each individual is the entire single line of humanity up through himself. If he represents descending development, decay, chronic degeneration, disease (illnesses are fundamentally consequences of decay, not its causes), then they are of little value.[33]

In the notebook entry that might correspond to this aphorism, Nietzsche discusses at length the social consequences of the rule of the descendant line. In essence, these are all of the prime characteristics of Judeo-Christian morality and political modernity: a preponderance of moral value judgments, resentment, altruism for the weak, and hatred of the strong and vital.[34] We must assume that these societal features are either the symptoms or causes of physiological and instinctual decline, as they are consistently described as intertwined with bodily weakness and decadence.

By understanding moral judgments as symptoms of physiological thriving or failure, Nietzsche is able to explain the conditions of preservation and growth represented in these lines of development. Forms of life, more specifically, ascendant and descendant forms of life, he explains, “educate the will” through morality, art, and aesthetics.[35] These produce what he calls “regulating instincts,” which, in ascending forms of life, stimulate to pride, joy, health, enmity and war, reverence, strong will, the discipline of high intellectuality, and gratitude toward life.[36] The problem with modernity is that it was formed as part of Christianity’s war against these types of instincts. It has, as he says, taken the side of everything weak and degenerate. Thus, the modern Last Man has poor instincts – those that desire what is harmful to the flourishing of strength, pride, and beauty.[37] As we have seen, the only way to overcome “poor instincts” is by self-overcoming – by transvaluing what is valued by descending forms of life.

Conclusion: Breeding Beauty and Strength

In contrast to the bourgeois “universal green-pasture happiness,” security, harmlessness, comfort, and easy living that has softened the instincts and bodies of the Last Man, Nietzsche suggests a festival of pride, exuberance, and unruliness; and an exclamatory Yes to oneself.[38] “Aristocraticism of the mind,” he says, must consist of pathos of distance from vulgarity, failures, weaklings, and the mediocre.[39]

Once again, we see Nietzsche returning to the Greeks as a curative to modern decadence, for the “festival” he describes matches “middle period” explanations of Greek pride.[40] But it is possible to read this description of the modern features from which one should feel a great distance as a curative of bodily decadence as well. Consciousness, explains Nietzsche, is a part of the body’s communication system, in that what we become aware of (and make communicable) is only that which serves the herd instincts of the human. It is “really just a net connecting one person with another,” he says, “the solitary and predatory person would not need it.” Because “becoming conscious” involves thought, and that “conscious thinking takes place in words, that is communication symbols,” the very ability to know oneself presupposes that one will do so only in terms useful to the herd/community.[41] Although thought is tainted with the herd, action, he says, is inherently personal, because, for the ascendant type at least, the body has the capacity to match “noble” instincts. This leads us back to the idea that great health and vitality are beyond truth.

But it also begs an examination of the role of the immediate environment in the body’s instinctual activity at any moment.

Sit as little as possible; do not believe any idea that was not conceived while moving around outside with your muscles in a celebratory mode as well. All prejudices come from the intestines – sitting down – I have said it before – is a true sin against the Holy Spirit.[42]

Nietzsche’s preferred method of working since at least Human, All Too Human was to walk or hike with a small notebook – carried either by himself or a companion – in which to note his various, evidently rapidly occurring thoughts. He not only felt it a “sin” to sit down but to wake in the morning and read a book. This was the habit of his Basel colleagues, and it helped Nietzsche’s attitude against academics to harden into contempt. These were men suited for the civil service, with wills to match their morbid bodies, he noted.[43]

In critiquing the philologists’ squandering of moments most full of vital energy on books, and in turn, creating a body of work (certainly not a philosophy) based on idleness, Nietzsche was working from the premise that conceptual vitality – philosophy itself – depended on the body’s instinctual vitality – what he called in Ecce Homo, the “surplus of life,” or superabundance of bodily energy flowing freely from the will and instincts.[44]

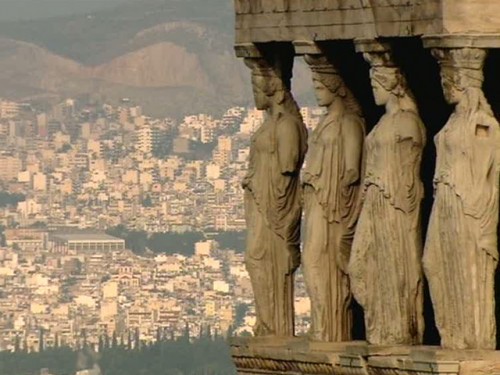

While he certainly understood transvaluation as part of the undamming of these forces, he also demanded that the body be made to move in order to create most vitally. It certainly seemed to help, as well, that the body move in beautiful environs. Nice, Genova, Sils-Maria, and Torino are striking in their man-made and natural beauty, combining the human nobility he so desired with demanding topographical harshness.[45]

With this in mind we may extrapolate from the “aristocratic festival” the true purpose of the Greek idealization of beauty and creativity. If form equals content, if the mind and body are one and the same, if “the will strives for purity and ennoblement,” then what did the Greeks gain from surrounding themselves with so much beauty? What, in turn, is the cost of modern vulgarity and lack of beauty?

Once again, the distance between the Greeks and moderns makes itself known, for we must remember that Greek and Nietzschean beauty does not prohibit violence or harshness. In fact, as an ascendant element of life, it could not exist without them. While for Nietzsche this had much to do with a transvaluation of modern softness, for the Greeks (Nietzsche’s “Greeks” were always pre-Socratic) it was natural and divine to equate beauty with the extreme effort required for its creation.

With the ideal of the Greeks in mind, Nietzsche began thinking of a new form of life to be made possible by breeding strength. He saw in it another grand transvaluation of the entire sum of modern institutions and values; of the “progressive diminishment” of man’s “will, responsibility, self-assurance, and capacity to set self-serving goals.” To fight this, he recommends moral and ethical systems (at a societal level) that value self-selection and hardship, education only to benefit the higher type of man, distance between ascendant and descendant types, and freely adopting all values that are forbidden by modernity.[46]

Elsewhere, he explains that, as long as democratic and socialist “ideas” are fashionable, it will be impossible for humanity to move en masse toward an ascendant form of life. However, he says, anyone who has studied life on earth understands the optimal conditions for “breeding strength:” “danger, harshness, violence, inequality of rights, . . . in short the antithesis of everything desirable for the herd.”[47] This “fire next time” scenario is of great contrast with the exuberance and pride of individual self-overcoming, but these are not necessarily contradictory as much as complimentary.

For in embracing strength, one must reject weakness; in embracing harshness, one must reject mildness; in embracing beauty, one must reject vulgarity; in embracing oneself, one must reject the mob. Once again, we’ve moved within and without the body, for overcoming the modern Last Man must begin with self-overcoming.

Notes

[1] Friedrich Nietzsche, “The Anti-Christ,” in The Anti-Christ, Ecce Homo, Twilight of the Idols, and Other Writings, trans. Judith Norman, ed. Judith Norman and Aaron Ridley (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 14 [17]. (All quotes from primary Nietzschean sources include page and aphorism number.)

[2] Christian J. Emden, Nietzsche on Language, Consciousness, and the Body (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2005), 138.

[3] Friedrich Nietzsche, Writings from the Early Notebooks, trans. Ladislaus Löb, ed. Raymond Geuss and Alexander Nehamas (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 24 (5[25]).

[4] Friedrich Nietzsche, Dawn: Thoughts on the Presumptions of Morality, trans. Brittain Smith (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2011), 77 [109].

[5] An interesting example of how the idea expressed in Dawn 109 evolved can be found in Beyond Good and Evil 36.

[6] Human, All Too Human (1878-1880), Dawn (1881), and The Gay Science (1882).

[8] Gary Handwerk, “Translator’s Afterword,” in Friedrich Nietzsche, Human, All Too Human II and Unpublished Fragments from the Period of Human, All Too Human II (Spring 1878-Fall 1879), trans. Gary Handwerk (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2013), 558.

[9] Fredrick Appel, Nietzsche Contra Democracy (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1999), 21.

[10] Horst Hutter, Shaping the Future: Nietzsche’s New Regime of the Soul and It’s Ascetic Practices (Lanham MD: Lexington Books, 2006), 146.

[11] Friedrich Nietzsche, Human, All Too Human I, trans. Gary Handwerk (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 1995), 112 [143].

[12] Paul E. Kirkland, Nietzsche’s Noble Aims: Affirming Life, Contesting Modernity (Lanham MD: Lexington Books, 2009), 11.

[13] Friedrich Nietzsche, “Ecce Homo,” in The Anti-Christ, Ecce Homo, Twilight of the Idols, and Other Writings, trans. Judith Norman, ed. Judith Norman and Aaron Ridley (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 75 [Wise 1].

[14] Friedrich Nietzsche, Ecce Homo, 77 [Wise 2].

[15] Dirk R. Johnson, Nietzsche’s Anti-Darwinism (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 77.

[16] Although it is problematic to discuss them separately – as to truly be the latter one must fully understand and embrace the former – the purposes of the Übermensch for this paper do not require a detailed examination of eternal recurrence.

[17] Friedrich Nietzsche, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, trans. Adrian Del Caro, ed. Adrian Del Caro and Robert B. Pippin (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2006), 22-24 [Despisers of the Body].

[18] Friedrich Nietzsche, Ecce Homo, 77 [Wise 2].

[19] Friedrich Nietzsche, Zarathustra, 8 [Prologue 4].

[20] Dirk R. Johnson, 59.

[21] Friedrich Nietzsche, Zarathustra, 9-11.

[22] Dirk R. Johnson, 60.

[23] Friedrich Nietzsche, Zarathustra, 10 [Prologue 5].

[24] Friedrich Nietzsche, Zarathustra, 134-136 [On Virtue that Makes Small 2, 3].

[25] Friedrich Nietzsche, Zarathustra, 136-137 [On Virtue that Makes Small 3].

[26] Friedrich Nietzsche, Zarathustra, 137 [On Virtue that Makes Small 3].

[27] Paul E. Kirkland, Nietzsche’s Noble Aims: Affirming Life, Contesting Modernity (Lanham MD: Lexington Books, 2009), 8.

[28] Curtis Cate, Friedrich Nietzsche (Woodstock, NY: The Overlook Press, 2002), 472.

[29] Friedrich Nietzsche, On the Genealogy of Morality, trans. Carol Dithe, ed. Keith Ansell-Pearson (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 85 [III 11].

[30] Friedrich Nietzsche, Genealogy, 85-86 [III 11].

[31] Dirk R. Johnson, 185.

[32] Friedrich Nietzsche, “Twilight of the Idols,” in The Anti-Christ, Ecce Homo, Twilight of the Idols, and Other Writings, trans. Judith Norman, ed. Judith Norman and Aaron Ridley (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 208 [Skirmishes 33].

[33] Friedrich Nietzsche, Twilight of the Idols, 208 [Skirmishes 33].

[34] Friedrich Nietzsche, Writings from the Late Notebooks, trans. Kate Sturge, ed. Rüdiger Bittner (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2003), 242 [14 (29) Spring 1888].

[35] Friedrich Nietzsche, Late Notebooks, 200 [10 (165) Autumn 1887].

[36] Friedrich Nietzsche, Late Notebooks, 242 [14 (11) Spring 1888].

[37] Friedrich Nietzsche, The Anti-Christ, 4-5 [3, 6].

[38] Friedrich Nietzsche, Late Notebooks, 201 [10 (165) Autumn 1887].

[39] Friedrich Nietzsche, The Anti-Christ, 40 [43].

[40] Friedrich Nietzsche, Dawn: Thoughts on the Presumptions of Morality, trans. Brittain Smith (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 2011), 190 [306].

[41] Friedrich Nietzsche, The Gay Science, trans. Josefine Nauckhoff, ed. Bernard Williams (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2001), 212-213 [354].

[42] Friedrich Nietzsche, Ecce Homo, 87 [Clever 1].

[43] Friedrich Nietzsche, Unpublished Writings from the Period of Unfashionable Observations, trans. Richard T. Gray (Palo Alto: Stanford University Press, 1995) 181-183 [28 (1) Spring-Autumn 1873].

[44] Friedrich Nietzsche, Ecce Homo, 110 [Birth of Tragedy 4].

[45] David F. Krell and Donald L. Bates, The Good European: Nietzsche’s Work Sites in Words and Images (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1997).

[46] Friedrich Nietzsche, Late Notebooks, 166 [9 (153) Autumn 1887].

[47] Friedrich Nietzsche, Late Notebooks, 31 [37 (8) June-July 1885].

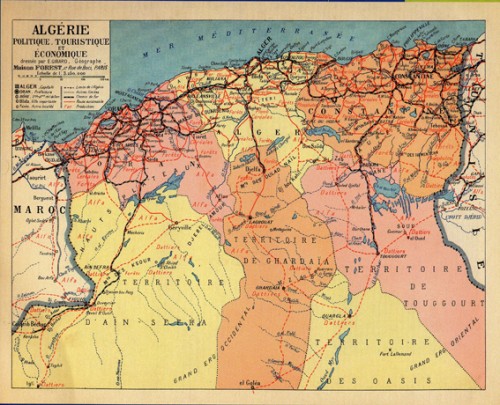

Si le nom de Carl Schmitt n’est plus tout à fait inconnu en France, où plus d’une dizaine de ses ouvrages ont déjà été traduits depuis 1972, sa personnalité reste encore très controversée. Grand théoricien du droit constitutionnel et international de l’Allemagne de l’entre deux guerres, son attitude à l’égard du nazisme lui valut d’être emprisonné plus d’une année après 1945. Refuser d’aller plus loin serait pourtant regrettable, comme ceux qui voudront bien ouvrir Le nomos de la terre s’en rendront rapidement compte. Publié en 1950 et composé dans des conditions difficiles, ce gros ouvrage offre une vue d’ensemble sur la pensée de l’auteur et passe à bon droit pour son oeuvre maîtresse.

Si le nom de Carl Schmitt n’est plus tout à fait inconnu en France, où plus d’une dizaine de ses ouvrages ont déjà été traduits depuis 1972, sa personnalité reste encore très controversée. Grand théoricien du droit constitutionnel et international de l’Allemagne de l’entre deux guerres, son attitude à l’égard du nazisme lui valut d’être emprisonné plus d’une année après 1945. Refuser d’aller plus loin serait pourtant regrettable, comme ceux qui voudront bien ouvrir Le nomos de la terre s’en rendront rapidement compte. Publié en 1950 et composé dans des conditions difficiles, ce gros ouvrage offre une vue d’ensemble sur la pensée de l’auteur et passe à bon droit pour son oeuvre maîtresse.

In “The Religious Life” in Human, All Too Human, he follows the latter path to a scathing conclusion: “the saint” is the product of “a sick nature . . . spiritual poverty, faulty knowledge, ruined health, and overexcited nerves.”[11] In other words, the saint is the product of his derelict body and impoverished instincts, and not some metaphysical deity or utopia; just as all behaviors and concepts can be related to the physiological state of their human bearers. This type of analysis served Nietzsche well in his later examinations of the origins of morality. It demonstrates that physiology was not merely a metaphorical platform for explaining human behavior, but in fact, a philoso-scientific way of naturalizing even the most exalted of ethico-behavioral schemes.

In “The Religious Life” in Human, All Too Human, he follows the latter path to a scathing conclusion: “the saint” is the product of “a sick nature . . . spiritual poverty, faulty knowledge, ruined health, and overexcited nerves.”[11] In other words, the saint is the product of his derelict body and impoverished instincts, and not some metaphysical deity or utopia; just as all behaviors and concepts can be related to the physiological state of their human bearers. This type of analysis served Nietzsche well in his later examinations of the origins of morality. It demonstrates that physiology was not merely a metaphorical platform for explaining human behavior, but in fact, a philoso-scientific way of naturalizing even the most exalted of ethico-behavioral schemes.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Uiteraard wilt dit niet zeggen dat wij volledig akkoord gaan met wat Tibor Machan elders schrijft, maar het is wel een denkoefening die we moeten maken. Als rechtsnationalisten wensen we immers dat de staat wel degelijk ingrijpt in bepaalde materies. Wij wensen echter geen staat die zodanig veel angst heeft voor haar burgers dat de enige oplossing van de heersende elite de instelling van een totalitair systeem is. Dan dient er immers

Uiteraard wilt dit niet zeggen dat wij volledig akkoord gaan met wat Tibor Machan elders schrijft, maar het is wel een denkoefening die we moeten maken. Als rechtsnationalisten wensen we immers dat de staat wel degelijk ingrijpt in bepaalde materies. Wij wensen echter geen staat die zodanig veel angst heeft voor haar burgers dat de enige oplossing van de heersende elite de instelling van een totalitair systeem is. Dan dient er immers

Le mercredi 7 novembre, lors du forum économique de l’hebdomadaire de Hambourg Die Zeit, l’ancien chancelier Helmut Schmidt a déclaré, devant 600 invités de l’économie et de la politique, qu’avec la crise de surendettement en arrière-plan, il n’est pas impensable qu’il y aura de profonds changements politiques et économiques. «Nous nous trouvons à la veille d’une possible révolution en Europe», prévient Schmidt. Il pressent que dans toute l’Europe la confiance dans les institutions européennes a diminué. La situation en Chine et aux Etats-Unis est également caractérisée par des incertitudes.

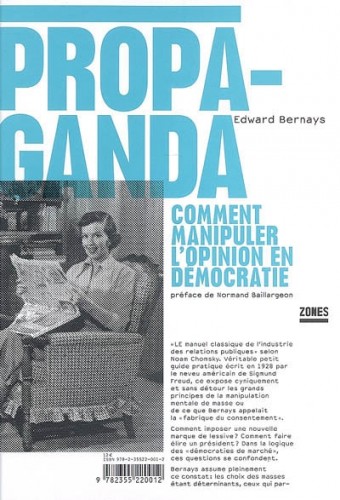

Le mercredi 7 novembre, lors du forum économique de l’hebdomadaire de Hambourg Die Zeit, l’ancien chancelier Helmut Schmidt a déclaré, devant 600 invités de l’économie et de la politique, qu’avec la crise de surendettement en arrière-plan, il n’est pas impensable qu’il y aura de profonds changements politiques et économiques. «Nous nous trouvons à la veille d’une possible révolution en Europe», prévient Schmidt. Il pressent que dans toute l’Europe la confiance dans les institutions européennes a diminué. La situation en Chine et aux Etats-Unis est également caractérisée par des incertitudes.  Edward Bernays (1891-1995), neveu de Sigmund Freud émigré aux Etats-Unis, est considéré comme le père de la propagande politique institutionnelle et de l’industrie des relations publiques, dont il met au point les méthodes pour des firmes comme Lucky Strike. Son œuvre aborde des thèmes communs à celle de

Edward Bernays (1891-1995), neveu de Sigmund Freud émigré aux Etats-Unis, est considéré comme le père de la propagande politique institutionnelle et de l’industrie des relations publiques, dont il met au point les méthodes pour des firmes comme Lucky Strike. Son œuvre aborde des thèmes communs à celle de  Car l’homme fait partie de ce « gouvernement de l’ombre », aujourd’hui « spin doctors » et autres conseillers en relation publique, qui régit toutes les activités humaines, du choix de nos lessives aux décisions de nos chefs d’Etat. A travers ses multiples exemples aux allures de complot, son oeuvre, Propaganda, est tout à la fois une théorie des relations publiques et le guide pratique de cette « ingénierie du consentement ».

Car l’homme fait partie de ce « gouvernement de l’ombre », aujourd’hui « spin doctors » et autres conseillers en relation publique, qui régit toutes les activités humaines, du choix de nos lessives aux décisions de nos chefs d’Etat. A travers ses multiples exemples aux allures de complot, son oeuvre, Propaganda, est tout à la fois une théorie des relations publiques et le guide pratique de cette « ingénierie du consentement ».

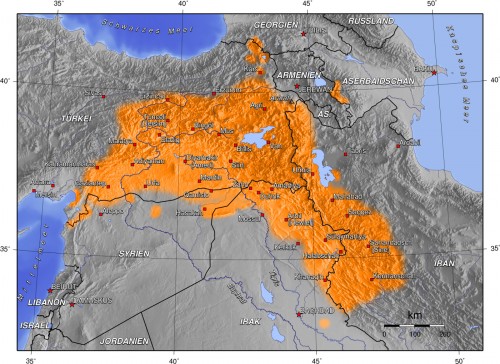

Londres vient de rejeter le requête de Washington: les Etats-Unis ne pourront pas utiliser les bases militaires britanniques pour d’éventuelles actions contre l’Iran. Les Britanniques avancent pour argument que toute attaque préventive contre Téhéran constituerait une violation du droit international, vu que la République Islamique ne représente pas, ajoutent-ils, une “menace claire et immédiate”. C’est du moins ce qu’écrit le “Guardian”, qui cite des sources gouvernementales britanniques. Selon le célèbre quotidien, Washington aurait demandé à pouvoir utiliser les bases militaires britanniques de Chypre, celles de l’Ile de l’Ascension (au milieu de l’Atlantique) et de Diego Garcia dans l’Océan Indien. A la suite de cette requête américaine, Londres aurait commandé une sorte d’audit légal au Procureur général du Royaume, puis à Downing Street, au Foreign Office et au ministère de la Défense. “La Grande-Bretagne violerait le droit international si elle venait en aide à une opération qui équivaudrait à une attaque préventive contre l’Iran”, a déclaré un haut fonctionnaire britannique au “Guardian”; et il ajoute: “le gouvernement a utilisé cet argument pour rejeter les demandes américaines”.

Londres vient de rejeter le requête de Washington: les Etats-Unis ne pourront pas utiliser les bases militaires britanniques pour d’éventuelles actions contre l’Iran. Les Britanniques avancent pour argument que toute attaque préventive contre Téhéran constituerait une violation du droit international, vu que la République Islamique ne représente pas, ajoutent-ils, une “menace claire et immédiate”. C’est du moins ce qu’écrit le “Guardian”, qui cite des sources gouvernementales britanniques. Selon le célèbre quotidien, Washington aurait demandé à pouvoir utiliser les bases militaires britanniques de Chypre, celles de l’Ile de l’Ascension (au milieu de l’Atlantique) et de Diego Garcia dans l’Océan Indien. A la suite de cette requête américaine, Londres aurait commandé une sorte d’audit légal au Procureur général du Royaume, puis à Downing Street, au Foreign Office et au ministère de la Défense. “La Grande-Bretagne violerait le droit international si elle venait en aide à une opération qui équivaudrait à une attaque préventive contre l’Iran”, a déclaré un haut fonctionnaire britannique au “Guardian”; et il ajoute: “le gouvernement a utilisé cet argument pour rejeter les demandes américaines”.