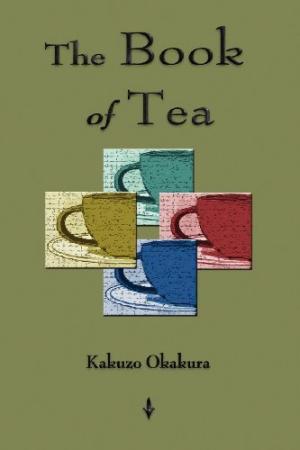

Despite his claim that the cultural crisis brought on by worldwide technological advancement could not be solved by a wholesale adoption of Eastern traditions such as Zen Buddhism, Martin Heidegger engaged in many conversations with… Japanese scholars throughout his philosophical career. His first and perhaps most significant encounter with the East took place as early as 1919, eight years before the publication of Being and Time. After having attended Heidegger’s 1918 lectures, one of his Japanese students, Tomonobu Imamichi, introduced Heidegger to the concept of “being in the world.” In The Book of Tea (1906), Tomonobu’s teacher, Okakura Kakuzo had used these words to describe an aspect of Zhuangzi’s spiritual vision.

Despite his claim that the cultural crisis brought on by worldwide technological advancement could not be solved by a wholesale adoption of Eastern traditions such as Zen Buddhism, Martin Heidegger engaged in many conversations with… Japanese scholars throughout his philosophical career. His first and perhaps most significant encounter with the East took place as early as 1919, eight years before the publication of Being and Time. After having attended Heidegger’s 1918 lectures, one of his Japanese students, Tomonobu Imamichi, introduced Heidegger to the concept of “being in the world.” In The Book of Tea (1906), Tomonobu’s teacher, Okakura Kakuzo had used these words to describe an aspect of Zhuangzi’s spiritual vision.

The Book of Tea uses the tea ceremony to explore the wabi-sabi aesthetic experience cultivated in Japanese Zen arts and crafts. The early German translation of The Book of Tea uses the words das-in-der-Welt-sein, which, via Imamichi, found their way into the heart and soul of Heidegger’s 1927 magnum opus. Interestingly, Heidegger’s philosophical career not only begins under Japanese influence, it also ends with it. One of the essays in his last work On the Way to Language is “A Dialogue on Language” between “a Japanese and an inquirer” who remain significantly unnamed…

The Book of Tea uses the tea ceremony to explore the wabi-sabi aesthetic experience cultivated in Japanese Zen arts and crafts. The early German translation of The Book of Tea uses the words das-in-der-Welt-sein, which, via Imamichi, found their way into the heart and soul of Heidegger’s 1927 magnum opus. Interestingly, Heidegger’s philosophical career not only begins under Japanese influence, it also ends with it. One of the essays in his last work On the Way to Language is “A Dialogue on Language” between “a Japanese and an inquirer” who remain significantly unnamed…

In his “Introduction to Heideggerian Existentialism”, Leo Strauss makes much of Heidegger’s ‘Eastern’ response to the crisis of world-enframing technology in the absence of a genuine global society. Strauss observes that modern technology is forcing the material conditions of a World Society upon us, without a common world culture as its basis. It is the unification of mankind on the basis of the lowest common denominator. This leads to “lonely crowds” suffering from a pervasive sense of alienation and anomie. Furthermore, Strauss recognizes that no genuine culture in the world has ever arisen without a religious basis, without addressing man’s need for something noble and great beyond himself. So the world society, being wrought largely as a consequence of apparently valueless technological forces, is ironically one in need, not merely of a universal ethics, but of one world religion. The world religion must emerge out of the deepest reflection on the crisis of cultural relativism, and on the essence of the technological forces bringing it about:

[Heidegger] called it the “night of the world.” It means indeed, as Marx had predicted, the victory of an ever more completely urbanized, ever more completely technological West over the whole planet – complete leveling and uniformity… unity of the human race on the lowest level, complete emptiness of life… How can there be hope? Fundamentally, because there is something in man which cannot be satisfied by the world society: the desire for the genuine, for the noble, for the great. The desire has expressed itself in man’s ideals, but all previous ideals have proved to be related to societies which were not world societies. The old ideals will not enable man to overcome the power, to weaken the power, of technology. We may also say: a world society can be human only if there is a world culture, a culture genuinely uniting all men. But there never has been a high culture without a religious basis: the world society can be human only if all men are genuinely united by a world religion.

Explicating Heidegger, Strauss explains that in order for it to be possible to overcome technology, which is not at all the same as rejecting it, there must be a sphere of thought or contemplation beyond the rationalism developed by the Greeks and forwarded in Western science and technology. This must be an understanding of the world from behind or beneath the will to mathematize all beings with a view to instrumental manipulation of them on demand (bestand). It must understand the difference between Being and beings, and that Being is no-thing that can be mastered. The to be which is always as present at hand, is taken by Rationalism as the standard of being – that which really is, is always present, available, accessible. Instead, Strauss thinks that: “a more adequate understanding of being is intimated by the assertion that to be means to be elusive or to be a mystery.” Strauss claims that “this is the Eastern understanding of Being” and he adds that: “We can hope beyond technological world society, we can hope for a genuine world society, only if we become capable of learning from the East… Heidegger is the only man who has an inkling of the dimensions of the problem of a world society.”

…The thinkers of the Kyoto School of Philosophy were in favor of the war and have been collectively referred to as the “philosophers of nothingness”. Some of them had a constructive vision of how the Buddhist understanding of the void could complement the techno-scientific thinking of the West in order to bring about a new global civilization. Key figures among them, such as Nishida Kitaro, were students of Heidegger as early as the 1920s, and like Heidegger they saw the world war as the means to bring about a global culture that would ground techno-scientific development in a spirituality transcending insular and traditional values.

…The thinkers of the Kyoto School of Philosophy were in favor of the war and have been collectively referred to as the “philosophers of nothingness”. Some of them had a constructive vision of how the Buddhist understanding of the void could complement the techno-scientific thinking of the West in order to bring about a new global civilization. Key figures among them, such as Nishida Kitaro, were students of Heidegger as early as the 1920s, and like Heidegger they saw the world war as the means to bring about a global culture that would ground techno-scientific development in a spirituality transcending insular and traditional values.

Remember that the Indian caste system that Nietzsche so admired, and that was based on regimented and hierarchically stratified class divisions, was a function of the Aryan conquest of the native Dravidian population of India. This origin is reflected in the Sanskrit name for the “caste” of the caste system, varna, which literally means “color” so that it was once a color-coding system. The four classes were: the Brahmins – the Vedic priests or scholars (including those who engaged in various proto-scientific practices); the Kshatriyas – the caste of knightly warriors, including feudal lords as chief amongst them; the Vaishyas – the business class, including both farmers and various types of merchants; and the Shudras – menial laborers, usually involved in undignified or hard labor. Finally, there were also “outcaste untouchables” that were relegated to an inhumanly low status. “Prince” Siddhartha Gotama belonged to the Kshatriya class.

The Buddha was a light-skinned blue eyed Aryan whose father was a feudal lord and who was expected to become a knight. In his late writings, Nishida Kitaro explains how it is that “Indian culture”, from which Japan inherited Buddhism (including the symbol of the swastika that is ubiquitous at Japanese temples) and which shares the Aryan or ‘Indo-European’ ethnic roots of European culture, “has evolved as an opposite pole to modern European culture… and may thereby be able to contribute to a global modern culture from its own vantage point.” What is the “global modern culture” that Nishida envisions?

Well, he certainly views it as having a religious basis and he thinks that the world war during which he is writing is a means to achieving it: “And does not the spirit of modern times seek a religion of infinite compassion rather than that of the Lord of ten thousand hosts? It demands reflection in the spirit of Buddhist compassion. This is the spirit which says that the present world war must be for the sake of negating world wars, for the sake of eternal peace.” In every true religion the divine is an absolute love that embraces its opposite, to the extent of even becoming Satan, and this is the meaning of the concept of upaya or shrewdly bringing to bear “skillful means” in Mahayana Buddhism so that “the miracles” of “this world may be said to be… the Buddha’s expedient means.” This all-embracing character of the divine, as that which encompasses what one would take to be its opposite, “is the basic reason why we are beings who can be compassionate to others and who can experience the compassion of others. Compassion always signifies that opposites are one in the dynamic reciprocity of their own contradictory identity.”

A God who is the Lord (Dominus) in the sense of an ultimately transcendent substance cannot be a truly creative God. Creation ex nihilo would be both arbitrary and superfluous; it must be out of love that God or Buddha creatively manifests the world from out of its own self-negation. Nishida believes that the school of Prajnaparamita thought in Mahayana Buddhism, established by Nagarjuna, has a deeper and more adequate understanding of this than pantheistic Western thinkers of dialectical synthesis, such as the Hegelians, who remain within the realm of reason even in their negative theologies. Nishida nevertheless refers to his ontology of the absolute’s self-expression and transformation as “Trinitarian” and compares it to Neo-Platonic thought.

However, Neo-Platonism and all pagan western thought falls short insofar as it fails to see Satan or “absolute evil” as an aspect of God. He adds: “The absolute God must include absolute negation within himself, and must be the God who descends into ultimate evil. The highest form must be one that transforms the lowest matter into itself. Absolute agape must reach even to the absolutely evil man. This is again the paradox of God: God is hidden even within the heart of the absolutely evil man. A God who merely judges the good and the bad is not truly absolute.” In passages such as these we see that Shunyata (in Sanskrit, Mu in Japanese) is not the Nothing of Descartes at all. Quite to the contrary of serving as an entirely distinct polar opposite of a Perfect Being that would exonerate the latter from being the source of any imperfection, this Nothingness is an inner dynamic tension within Being – as expressed in the spectral incompleteness and interdependent interpenetration of all beings. The battle between God and Nothingness in the heart of man, the “dynamic equilibrium” between “is” and “is not”, may be paradoxical but it is also the existential ‘ground’ of the volitional person. “Radical evil” lies ineradicably at the root of our freedom. We are always already “both satanic and divine.” Nishida claims that the Buddha – or any other conception of divinity – outside of one’s own existential potentiality is not the true Buddha:

Only in this existential experience of religious remorse does the self encounter what Rudolf Otto calls the numinous. Subjectively speaking, the encounter is a deep reflection upon the existential depths of the self itself; and as the Buddhists say, it means to see our essential nature, to see the true self. In Buddhism, this seeing means, not to see Buddha objectively outside, but to see into the bottomless depths of one’s own soul. If we see God externally, it is merely magic. …Illusion is the fountainhead of all evil. Illusion arises when we conceive of the objectified self as the true self. The source of illusion is in seeing the self in terms of object logic. It is for this reason that Mahayana Buddhism says that we are saved through enlightenment. But this enlightenment is generally misunderstood. For it does not mean to see anything objectively… It is rather an ultimate seeing of the bottomless nothingness of the self that is simultaneously a seeing of the fountainhead of sin and evil.

In this Zen injunction to kill any conception of a Buddha outside oneself, Nishida does not deny the cycle of birth and death or samsara as an empirical or phenomenological fact, he simply insists that the truly religious consciousness is one that has recognized the identity of samsara and nirvana. On his terms, and according to the sages of the esoteric Buddhist tradition, nirvana does not mean to attain some state distinct from and after samsara but to recognize that in every moment of the cycle of reincarnation the perfection beyond the impurity of karma is already present. This does not mean that the self “transcends its own historical actuality – it does not transcend its own karma – but rather that it realizes the bottomless bottom of its own karma.”

This relatively late Mahayanist view is anathema to the teaching of Siddhartha Gotama and the early Indian Buddhism founded on it. According to the Buddha Dharma, just as there are physical, biological, and psychological laws operative in the cosmos, there is also an ethical law. The law of karma is a lawful relationship between one’s actions, including verbal and unspoken mental acts that express one’s volition (cetana), and both the realm within which one is reborn as well as the conditions of life that one experiences within this realm. The ethical quality of one’s volition is supposed to resonate with the qualitative character of a certain realm of existence, and to tune into this realm, as it were, as a consequence of being on the same wavelength. Within these more general parameters what one experiences within a given realm of existence is conditioned by one’s actions both within the present life and in past lives. The fundamental presupposition here is that even if an action or intention does not appear to bear fruit (phala) presently, it reverberates in ways that one may remain unconscious of until it finally yields some tangible results (vipaka) – possibly later in one’s present life, but perhaps not until a future life.

While psychological research in the wake of the coming spectral revolution in Science might validate certain classes of phenomena associated with Buddhism as genuine natural phenomena, it is likely to reveal significant Buddhist misunderstandings of these very same phenomena and to profoundly challenge Buddhist codes of ethics. This is the case with the Reincarnation research of the late Dr. Ian Stevenson… What would disturb Buddhists most about Stevenson’s apparent validation of one of the central tenants of their religion is that the ethical idea of karma is untenable in light of his scientific research into the reality of Reincarnation as a natural phenomenon. What Stevenson found is that a person’s strong psychic impression of localized bodily injury at the time of a violent death or terrible accident, could affect fetal development of the body to be subsequently inhabited by that person to produce a birthmark or birth defect corresponding to the site of injury and even the shape or type of injury. In other words there are many cases of the following type: an innocent person is attacked and has his arm hacked off by a murderer and while the victim is reborn with that arm badly deformed, the murderer not only gets away scot free in his present incarnation, he also does not suffer any apparent ill effects in his subsequent incarnation.

Nirvana is the goal of the path, the aim of the Buddha Dharma. Yet, it is the most obscure element of Gotama’s teachings and, unlike karma, meditation, and the moral disciplines, it is one of the ideas most unique to his understanding of the Dharma as compared to the various pre-Buddhist forms of Sanatana Dharma (aka. ‘Hinduism). It is referred to at times as an element or a state, a state of supreme bliss, and yet it is supposed to be beyond any conditioned state, whether painful or even pleasurable. At times Siddhartha discusses Nirvana as if it were attainable amidst the present life and at other times it seems like a total annihilation that a perfectly enlightened person can pass into upon the disintegration of what will be his final body. What, then, is the difference between this annihilation and the so-called “annihilationism” that is one of the wrong views most destructive of an ethical life? Is the Buddha Dharma, in its original form, essentially a grand doctrine of suicide? Does it opt out of actual suicide because it will not do any good, since the underlying tendencies of the psyche are still active and will reorganize around a new physical aggregate, so that suicide can only be truly successful by unbinding the threads of this psyche – by disintegrating the soul?

Nirvana means “snuffing out” or “blowing out”, as in putting out a flame or fire. Orthodox Buddhists of the Theravada tradition most directly descended from the teachings of Gotama suggest that the answer to the perplexing question as to who attains Nirvana and where he attains it, namely as to whether a Buddha or arahant exists in Nirvana after death or is annihilated and passes into nothingness, can be simply answered by saying that the perfectly enlightened person simply “goes out” or is “put out.” He was a flame burning with the fire of life, but this fire of ceaseless suffering has been put out. Phew! Can there be a more pessimistic and nihilistic view of life? At least the man who actually commits suicide affirms a life that would be worth living by comparison to his own, which he judges intolerable only as compared to some ideal. He would also be affirming a sense of history wherein the future can be meaningfully different from any past epoch, an understanding of time that warrants a historical struggle – even if not one that he can personally bear to participate in here and now. It is above all in Japan where this early Buddhist nihilism gave way to the world-historical ethos of the fiery forge.

Nishida draws a distinction between physical, biological, and historical life. The teleological irreversibility of time in the course of organic development is key to his distinction between the first two. Whereas the world of biological life forms remains partially spatial and material, in the human world time negates space and the spatialized chronological ‘time’ relevant to inorganic physics. As Nishida puts it: “We can even say that there is no death for a merely biological being. For death entails that a self enter into eternal nothingness. It is because a self enters into eternal nothingness that it is historically irrepeatable, unique, and individual.” Only in the face of this “eternal death” qua nothingness is genuine individuation possible and only the real individual becomes agitated by the religious question. A being who carries out its moral duty for duty’s sake, in other words out of adherence to what Kant frames as the categorical imperative, would have no individuality; religion can have no meaning for such an abstract subject without any concrete will. Groundless nothingness (Shunyata) is the unstable and ghostly horizon of one’s finite existence, and existential awareness of this ultimate and inescapable negation of one’s self is not a merely noetic reflection.

Nishida approvingly attributes to Fyodor Dostoyevsky the “standpoint of freedom” which holds that: “There is nothing at all that determines the self at the very ground of the self.” From the vantage point of his own time, Nishida sees the spirit of Dostoyevsky as the closest point of contact between Japanese spirituality and the West. He admonishes the Japanese for having remained too insular and that the spiritual sense for the ordinary and everyday that Japan shares with Dostoyevsky has hitherto been too superficial. “At this juncture,” he says, “it must come to possess an acute Dostoievskian spirit in an eschatological sense, as the Japanese spirit participating in world history.” Nishida hopes that “in this way” the hybridized Japanese civilization “can become a point of departure for a new global culture.” Nishida sees the way that the Yahweh “folk religion of the Jewish race” evolved into a world religion, and one that served as the basis for a medieval European culture that he clearly admires, as a model for a potential globalizing evolution of Japanese tradition. The “scientific” secularization characteristic of modern Western civilization, wherein “old worlds lose their specific traditions”, is a necessary phase in the formation of “a global humanity.” It is, in a dialectical sense, a negatively determinative moment in “the world’s transformation.” However, it must be recognized that “science is also a form of culture” and that “the world of science may also be said to be religious.” The failure to recognize this has been chiefly responsible for the fact that “such a thing as the decline and fall of the West has been proclaimed.”

Dostoyevsky diagnosed the causes of this decline perspicaciously in Notes From Underground (1864), which is widely considered the first existentialist novel. It is a response to the situation of the Cartesian ego, which… is sadistically enmeshed in murderous machinery over which he takes himself to have no control. The underground man is crippled by his hyperconsciousness. He is unlike the common man of action insofar as he can trace all effects back to ever receding causes such that, for example, he is incapable of mistaking vengeance for justice, since the would-be target of a retributive act is not ultimately responsible for it. He is also unlike people who are cruel only out of stupidity, because he cannot even stop at the egoistic passions that they take to be primary causes. Under a more intensely rational scrutiny, comprehending these passions also dissolves them as any solid basis for action. The underground man challenges the claim that other materialistic rationalists make, to the effect that a person cannot but act in such a way as is to his advantage.

Dostoevsky asks us to suppose that we were able to arrive at a formulation of the laws of nature, including biological and psychological laws, so precise that we could calculate, in every case, what a man will do by knowing what is at that moment to his advantage – not as an individual – but as an organism that microcosmically expresses the survivalist egoism of Nature. A man who became aware of this calculation would spitefully do something else, anything else, just to prove that he was not “a piano key” or an “organ pedal” whose thoughts and passions could in principle be encompassed by a formula, tabulated, and predicted according to statistical probability. Dostoevsky equates the sum total of any comprehensive formula for the laws of nature, of the kind that physicists today are still searching for under the rubric of a theory of everything, with “an endlessly recurring zero” because it nullifies meaningful action.

Dostoevsky asks us to suppose that we were able to arrive at a formulation of the laws of nature, including biological and psychological laws, so precise that we could calculate, in every case, what a man will do by knowing what is at that moment to his advantage – not as an individual – but as an organism that microcosmically expresses the survivalist egoism of Nature. A man who became aware of this calculation would spitefully do something else, anything else, just to prove that he was not “a piano key” or an “organ pedal” whose thoughts and passions could in principle be encompassed by a formula, tabulated, and predicted according to statistical probability. Dostoevsky equates the sum total of any comprehensive formula for the laws of nature, of the kind that physicists today are still searching for under the rubric of a theory of everything, with “an endlessly recurring zero” because it nullifies meaningful action.

The underground man would act contrary to his advantage, he would humiliatingly sacrifice himself to others, to be beaten and brutalized, to be impoverished through impossible generosity, and in every other way to fail and suffer in life just so as to demonstrate that life “is not simply extracting square roots.” On the one hand, he knows that “two times two makes four”, in other words the laws of nature cannot be changed and so “there is nothing left for you to do or to understand.” On the other hand, he has a painful awareness that “Consciousness… is infinitely superior to two times two makes four.” The underground man decides that “if you stick to consciousness, even though you attain the same result, you can at least flog yourself at times, and that will, at any rate, liven you up. It may be reactionary, but corporal punishment is still better than nothing.”

If “natural science and mathematics” were able to prove to him that even this reaction were predictable in accordance with some “mathematical formula”, he “would purposely go mad in order to be rid of reason” and moreover, he would try to hurl the whole of the world into an abyss of “chaos and darkness and curses.” This is what the underground man is referring to when he admits:

The long and the short of it is, gentlemen, that it is better to do nothing! Better conscious inertia! And so hurrah for underground! …But after all, even now I am lying! I am lying because I know myself as surely as two times two makes four, that it is not at all underground that is better, but something different, quite different, for which I long but which I cannot find! Damn underground!

Nishida is in search of what the underground man could not find as a cure to the mechanistic materialism dominating science under the Cartesian paradigm, but what he believed that Dostoevsky himself did find – albeit in an overly Judeo-Christian form that would benefit from a deconstructive encounter with the abyssal void of Zen.

Consciousness always consists of both an extending out over oneself as one’s world and a determination of oneself by that world, so that ‘subjectivity’ and ‘objectivity’ are abstractions of a creative world-forming process that one can intuit in the abyssal or groundless inner depths of the self prior to the interpretation of it as an ego. Nishida thinks “discovery in the scientific domain exemplifies the same point”, namely “seeing by becoming things and hearing by becoming things.” Nishida goes so far as to proclaim the ontological priority of the religious form of life over both scientific practice and social mores: “Both science and morality have their basis in the religious form of life.” Nishida later repeats this point with respect to scientific practice: “Active intuition is fundamental even for science. Science itself is grounded in the fact that we see by becoming things and hear by becoming things. Active intuition refers to that standpoint which Dogen characterizes as achieving enlightenment ‘by all things advancing.’” According to Nishida, the religious form of life is more fundamental than scientific cognition and the knowledge gained by means of it; the quest for scientific knowledge is a mode of the essentially religious character of our existence:

I hold that even scientific cognition is grounded in this structure of spirituality. Scientific knowledge cannot be grounded in the standpoint of the merely abstract conscious self. As I have said in another place, it rather derives from the standpoint of the embodied self’s own self-awareness. And therefore, as a fundamental fact of human life, the religious form of life is not the exclusive possession of special individuals. The religious mind is present in everyone. One who does not notice this cannot be a philosopher.

Nishida proclaims that, “A new cultural direction has now to be sought. A new mankind must be born… a new global culture.” Although Nishida admits that “the new age must primarily be scientific”, he sees a radicalization of the immanent view of divinity in Dostoyevsky and Russian mysticism in general through an encounter with Japanese Buddhism as playing a key role in defining “the religion of the future.” Yet the Buddhism that contributes to the formation of the religion of the new age, the religion of the global culture, must transcend the racial character of the Japanese: “From the perspective of present-day global history, it will perhaps be Buddhism that contributes to the formation of the new historical age. But if it too is only the conventional Buddhism of bygone days, it will merely be a relic of the past. The universal religions, insofar as they are already crystallized, have distinctive features corresponding to the times and places of the races that formed them.” It is inevitable that our ethos reflects a national character, but “the nation does not save our souls.” A true nation or civilization must be based on a world religion, and not the other way around.

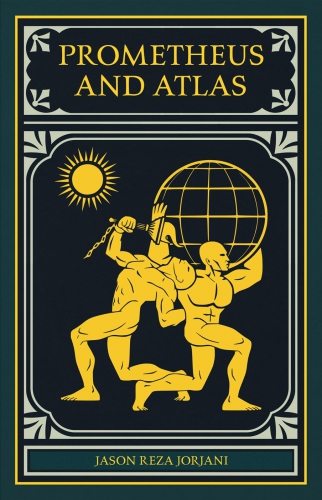

The has been an excerpt from “Kill A Buddha On The Way,” the tenth chapter of Prometheus and Atlas (Arktos, 2016).

Right On Radio: #8 – The Promethean Destiny of Man with Jason Reza Jorjani

Prometheus and Atlas

In Prometheus & Atlas, Dr. Jorjani endeavors to deconstruct the nihilistic materialism and rootless rationalism of the modern West by showing how it was grounded on a dishonest suppression of the spectral and why it has a parasitic relationship with Abrahamic religious fundamentalism. Rejecting the marginalization of ESP and psychokinesis as “paranormal,” Prometheus & Atlas […]

Price: $36.50

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Certains (par exemple, Robert Cramer) tentent de justifier cela en prétextant que nous vivons une situation un peu particulière et que c’est dans l’urgence que le pouvoir doit agir en attendant de pouvoir modifier la constitution (RASA et son/ses éventuel(s) contre-projet(s)). Pour ceux qui préfèrent que les choses soient dites concrètement, cela signifie que nous vivons un moment dans lequel une partie de la constitution est suspendue, que nos autorités disposent d’une situation de plein pouvoirs en la matière. Cela porte un nom : « dictature » même si personne n’ose le dire clairement.

Certains (par exemple, Robert Cramer) tentent de justifier cela en prétextant que nous vivons une situation un peu particulière et que c’est dans l’urgence que le pouvoir doit agir en attendant de pouvoir modifier la constitution (RASA et son/ses éventuel(s) contre-projet(s)). Pour ceux qui préfèrent que les choses soient dites concrètement, cela signifie que nous vivons un moment dans lequel une partie de la constitution est suspendue, que nos autorités disposent d’une situation de plein pouvoirs en la matière. Cela porte un nom : « dictature » même si personne n’ose le dire clairement.

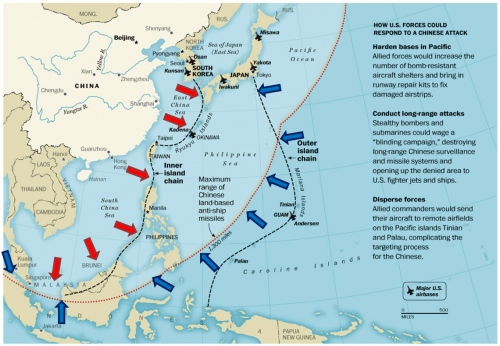

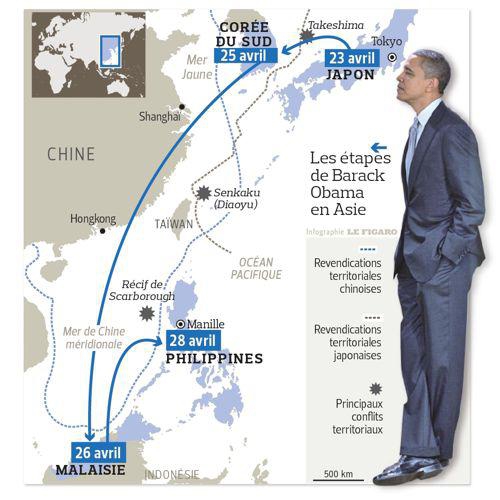

En Relations Internationales, rien n'exprime mieux le succès d'une théorie que sa reprise par la sphère politique. Au XXIe siècle, seuls deux exemples ont atteint cet état :

En Relations Internationales, rien n'exprime mieux le succès d'une théorie que sa reprise par la sphère politique. Au XXIe siècle, seuls deux exemples ont atteint cet état :  De là naît la nécessité pour les Etats, et principalement les Etats-Unis, de définir une véritable stratégie de puissance, de smart power. En effet, un Etat ne doit pas faire le choix d'une puissance, mais celui de la puissance dans sa globalité, sous tous ses aspects et englobant l'intégralité de ses vecteurs. Ce choix de maîtriser sa puissance n'exclue pas le recours aux autres nations. L'heure est à la coopération, voire à la copétition, et non plus au raid solitaire sur la sphère internationale. Même les Etats-Unis ne pourront plus projeter pleinement leur puissance sans maîtriser les organisations internationales et régionales, ni même sans recourir aux alliances bilatérales ou multilatérales. Ils sont voués à montrer l'exemple en assurant l'articulation politique de la multipolarité. Pour ce faire, les Etats-Unis devront aller de l'avant en conservant une cohésion nationale, malgré les déboires de la guerre en Irak, et en améliorant le niveau de vie de leur population, notamment par la réduction de la mortalité infantile. Cohésion et niveau de vie sont respectivement vus par l'auteur comme les garants d'un hard et d'un soft power durables. A contrario, l'immigration, décriée par différents observateurs comme une faiblesse américaine, serait une chance pour l'auteur car elle est permettrait à la fois une mixité culturelle et la propagation de l'american dream auprès des populations démunies du monde entier.

De là naît la nécessité pour les Etats, et principalement les Etats-Unis, de définir une véritable stratégie de puissance, de smart power. En effet, un Etat ne doit pas faire le choix d'une puissance, mais celui de la puissance dans sa globalité, sous tous ses aspects et englobant l'intégralité de ses vecteurs. Ce choix de maîtriser sa puissance n'exclue pas le recours aux autres nations. L'heure est à la coopération, voire à la copétition, et non plus au raid solitaire sur la sphère internationale. Même les Etats-Unis ne pourront plus projeter pleinement leur puissance sans maîtriser les organisations internationales et régionales, ni même sans recourir aux alliances bilatérales ou multilatérales. Ils sont voués à montrer l'exemple en assurant l'articulation politique de la multipolarité. Pour ce faire, les Etats-Unis devront aller de l'avant en conservant une cohésion nationale, malgré les déboires de la guerre en Irak, et en améliorant le niveau de vie de leur population, notamment par la réduction de la mortalité infantile. Cohésion et niveau de vie sont respectivement vus par l'auteur comme les garants d'un hard et d'un soft power durables. A contrario, l'immigration, décriée par différents observateurs comme une faiblesse américaine, serait une chance pour l'auteur car elle est permettrait à la fois une mixité culturelle et la propagation de l'american dream auprès des populations démunies du monde entier.

L’étude replace toujours l’action de l’agence dans le contexte historique tant international qu’étatsunien avec, en creux, une critique de la politique hégémonique des Etats-Unis. Comme elle l’avait fait dans son livre précédent avec Echelon (2) , l’auteure se penche sur les stratégies de domination technologique et informationnelle de la NSA et montre sans détour combien la maîtrise de l’information est un enjeu fondamental de suprématie pour des Etats-Unis de plus en plus concurrencés en tant que puissance mondiale. Et au XXIe siècle, l’enjeu est de garder la main dans le nouveau champ qu’est le cyberespace. La guerre globale contre le terrorisme au nom de la défense des valeurs démocratiques et de la sécurité des Etats-Unis n’est alors qu’un prétexte à maintenir un leadership mondial de plus en plus contesté. Détentrice du pouvoir de renseigner, la NSA constitue l’un des instruments de la puissance américaine et de la sauvegarde d’intérêts de plus en plus menacés.

L’étude replace toujours l’action de l’agence dans le contexte historique tant international qu’étatsunien avec, en creux, une critique de la politique hégémonique des Etats-Unis. Comme elle l’avait fait dans son livre précédent avec Echelon (2) , l’auteure se penche sur les stratégies de domination technologique et informationnelle de la NSA et montre sans détour combien la maîtrise de l’information est un enjeu fondamental de suprématie pour des Etats-Unis de plus en plus concurrencés en tant que puissance mondiale. Et au XXIe siècle, l’enjeu est de garder la main dans le nouveau champ qu’est le cyberespace. La guerre globale contre le terrorisme au nom de la défense des valeurs démocratiques et de la sécurité des Etats-Unis n’est alors qu’un prétexte à maintenir un leadership mondial de plus en plus contesté. Détentrice du pouvoir de renseigner, la NSA constitue l’un des instruments de la puissance américaine et de la sauvegarde d’intérêts de plus en plus menacés.

Pendant deux mois et demi, du 24 août au 8 novembre, Sylvain Tesson va parcourir ce qu'il nomme les chemins noirs, d'après le titre du livre de René Frégni,

Pendant deux mois et demi, du 24 août au 8 novembre, Sylvain Tesson va parcourir ce qu'il nomme les chemins noirs, d'après le titre du livre de René Frégni,

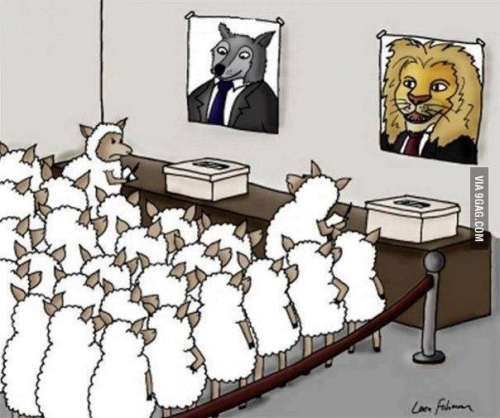

For this reason, in the words of Carl Schmitt, liberals have an undeveloped sense of the political, an inability to think of themselves as members of a political entity that was created with a clear sense of who can belong and who cannot belong in the community. Having a concept of the political presupposes a people with a strong sense of who can be part of their political community, who can be friends of the community and who cannot be because they pose a threat to the existence and the norms of the community.

For this reason, in the words of Carl Schmitt, liberals have an undeveloped sense of the political, an inability to think of themselves as members of a political entity that was created with a clear sense of who can belong and who cannot belong in the community. Having a concept of the political presupposes a people with a strong sense of who can be part of their political community, who can be friends of the community and who cannot be because they pose a threat to the existence and the norms of the community. Eventually, liberals came to believe that commerce would, in the words expressed by the Scottish thinker William Robertson in 1769, “wear off those prejudices which maintain distinction and animosity between nations.” By the nineteenth century liberals were not as persuaded by Hobbes’s view that the state of nature would continue permanently in the international relationships between nations. They replaced his pessimistic argument about human nature with a progressive optimism about how humans could be socialized to overcome their turbulent passions and aggressive instincts as they were softened through affluence and greater economic opportunities. With continuous improvements in the standard of living, technology and social organization, there would be no conflicts that could not be resolved through peaceful deliberation and political compromise.

Eventually, liberals came to believe that commerce would, in the words expressed by the Scottish thinker William Robertson in 1769, “wear off those prejudices which maintain distinction and animosity between nations.” By the nineteenth century liberals were not as persuaded by Hobbes’s view that the state of nature would continue permanently in the international relationships between nations. They replaced his pessimistic argument about human nature with a progressive optimism about how humans could be socialized to overcome their turbulent passions and aggressive instincts as they were softened through affluence and greater economic opportunities. With continuous improvements in the standard of living, technology and social organization, there would be no conflicts that could not be resolved through peaceful deliberation and political compromise. The negation of the political is necessarily implicit in the liberal notion that humans can be defined as individuals with natural rights. It is implicit in the liberal aspiration to create a world in which groups and nations interact through peaceful economic exchanges and consensual politics, and in which, accordingly, the enemy-friend distinction and the possibility of violence between groups is renounced. The negation of the political is implicit in the liberal notion of “humanity.” The goal of liberalism is to get rid of the political, to create societies in which humans see themselves as members of a human community dedicated to the pursuit of security, comfort and happiness. Therefore, we can argue with Schmitt that liberals have ceased to understand the political insomuch as liberal nations and liberal groups have renounced the friend-enemy distinction and the possibility of violence, under the assumption that human groups are not inherently dangerous to each other, but can be socialized gradually to become members of a friendly “humanity” which no longer values the honor of belonging to a group that affirms ethno-cultural existential differences. This is why Schmitt observes that liberal theorists lack a concept of the political, since the political presupposes a view of humans organized in groupings affirming themselves as “existentially different.”

The negation of the political is necessarily implicit in the liberal notion that humans can be defined as individuals with natural rights. It is implicit in the liberal aspiration to create a world in which groups and nations interact through peaceful economic exchanges and consensual politics, and in which, accordingly, the enemy-friend distinction and the possibility of violence between groups is renounced. The negation of the political is implicit in the liberal notion of “humanity.” The goal of liberalism is to get rid of the political, to create societies in which humans see themselves as members of a human community dedicated to the pursuit of security, comfort and happiness. Therefore, we can argue with Schmitt that liberals have ceased to understand the political insomuch as liberal nations and liberal groups have renounced the friend-enemy distinction and the possibility of violence, under the assumption that human groups are not inherently dangerous to each other, but can be socialized gradually to become members of a friendly “humanity” which no longer values the honor of belonging to a group that affirms ethno-cultural existential differences. This is why Schmitt observes that liberal theorists lack a concept of the political, since the political presupposes a view of humans organized in groupings affirming themselves as “existentially different.”

Par cet exemple simple, on comprend mieux le lien entre consommation, déracinement et individualisme. On comprend mieux aussi pourquoi on parlera de « fait anthropologique total ». Le rapport à l’Etat a aussi pour conséquence de renforcer l’individualisme : puisque l’État papa ou l’État maman est là (c.a.d : la version rassurante ou répressive de l’Etat), alors quel intérêt d’entretenir des liens de solidarité ? Nous sommes « seuls ensembles ». On devient un « sujet de l’Etat » et finalement tout le monde accepte tacitement le contrat : payer ses impôts pour avoir des « droits à » mais aussi le « droit de ». La loi prend la place de la coutume (locale) ou de la décence commune (pour replacer direct du Michéa).

Par cet exemple simple, on comprend mieux le lien entre consommation, déracinement et individualisme. On comprend mieux aussi pourquoi on parlera de « fait anthropologique total ». Le rapport à l’Etat a aussi pour conséquence de renforcer l’individualisme : puisque l’État papa ou l’État maman est là (c.a.d : la version rassurante ou répressive de l’Etat), alors quel intérêt d’entretenir des liens de solidarité ? Nous sommes « seuls ensembles ». On devient un « sujet de l’Etat » et finalement tout le monde accepte tacitement le contrat : payer ses impôts pour avoir des « droits à » mais aussi le « droit de ». La loi prend la place de la coutume (locale) ou de la décence commune (pour replacer direct du Michéa). Autre élément qu’on pourrait citer dans la décolonisation de l’imaginaire : le rapport au temps. Une des mutations anthropologique majeure induite par le progrès technique, c’est le changement de notre rapport au temps. On ne peut aller plus vite que le cheval que depuis la fin du XIXeme siècle. La « société de la vitesse » a donc émergée et aucun régime, y compris les régimes qui voulaient lutter contre l’homme libéral, n’a été contre la société de la vitesse. Il est nécessaire qu’il y ait une part prométhéenne mais on n’en maîtrise pas toujours les conséquences. La vitesse, si elle a contribué à la « grandeur des nations », a aussi favorisé une philosophie puis une pratique néo-nomadiste. Le déplacement fait parti de notre façon d’habiter le territoire. J’y reviendrai en troisième partie. Il faudrait donc repenser notre rapport au temps, prendre le temps, faire moins de « choses » mais mieux : la « philosophie de l’escargot » des décroissants.

Autre élément qu’on pourrait citer dans la décolonisation de l’imaginaire : le rapport au temps. Une des mutations anthropologique majeure induite par le progrès technique, c’est le changement de notre rapport au temps. On ne peut aller plus vite que le cheval que depuis la fin du XIXeme siècle. La « société de la vitesse » a donc émergée et aucun régime, y compris les régimes qui voulaient lutter contre l’homme libéral, n’a été contre la société de la vitesse. Il est nécessaire qu’il y ait une part prométhéenne mais on n’en maîtrise pas toujours les conséquences. La vitesse, si elle a contribué à la « grandeur des nations », a aussi favorisé une philosophie puis une pratique néo-nomadiste. Le déplacement fait parti de notre façon d’habiter le territoire. J’y reviendrai en troisième partie. Il faudrait donc repenser notre rapport au temps, prendre le temps, faire moins de « choses » mais mieux : la « philosophie de l’escargot » des décroissants.

Cela n’a pas réussi à tarir sa production littéraire, ni à le priver de son talent. D’autres éditeurs à l’esprit libre, Pierre-Guillaume de Roux, Fata Morgana, Léo Scheer, L’Orient des livres, Les Provinciales, publient ses dernières oeuvres. Province, roman sur le délitement de la société française, est la dernière en date.

Cela n’a pas réussi à tarir sa production littéraire, ni à le priver de son talent. D’autres éditeurs à l’esprit libre, Pierre-Guillaume de Roux, Fata Morgana, Léo Scheer, L’Orient des livres, Les Provinciales, publient ses dernières oeuvres. Province, roman sur le délitement de la société française, est la dernière en date.

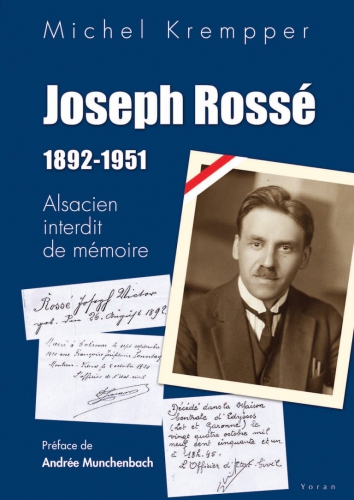

Mais de ses contacts avérés avec le colonel von Stauffenberg, le porteur de la bombe qui devait tuer le Führer le 20 juillet 1944, la justice politique de la Libération n’en tiendra nul compte. Il ne sera pas plus porté à sa décharge l’intense activité de Rossé pour venir en aide à ses compatriotes alsaciens victimes de l’hitlérisme ou pour éditer clandestinement les auteurs chrétiens interdits dans l’Allemagne nazie.

Mais de ses contacts avérés avec le colonel von Stauffenberg, le porteur de la bombe qui devait tuer le Führer le 20 juillet 1944, la justice politique de la Libération n’en tiendra nul compte. Il ne sera pas plus porté à sa décharge l’intense activité de Rossé pour venir en aide à ses compatriotes alsaciens victimes de l’hitlérisme ou pour éditer clandestinement les auteurs chrétiens interdits dans l’Allemagne nazie.

Lucie est une jeune Parisienne, fille d’un père aux convictions païennes et d’une mère chrétienne d’origine ukrainienne. Spécialiste des parfums, elle doit se rendre dans un pays oriental (dont le nom ne sera, à dessein, jamais indiqué) pour mener une recherche dans le cadre de son sujet d’étude, à savoir « l’histoire des odeurs et la mémoire des peuples ». Le thème des parfums reviendra d’ailleurs comme un leitmotiv tout au long du film, qui aurait tout à fait pu être une œuvre tournée en odorama ! Les choses ne se passent toutefois pas comme prévu et, peu après son arrivée, la jeune fille, trompée par un chauffeur de taxi, est livrée à un groupe de djihadistes qui la prennent en otage pour obtenir de l’argent de la France. L’histoire nous est racontée tour à tour selon trois perspectives : celle de Lucie, celle de Younes (le chauffeur de taxi en proie à un dilemme moral et que les difficultés économiques contraignent à se faire le complice des islamistes) et celle d’Abou (un djihadiste d’origine française qui va peu à peu être assailli de doutes sur son engagement à mesure que la situation se dégrade).

Lucie est une jeune Parisienne, fille d’un père aux convictions païennes et d’une mère chrétienne d’origine ukrainienne. Spécialiste des parfums, elle doit se rendre dans un pays oriental (dont le nom ne sera, à dessein, jamais indiqué) pour mener une recherche dans le cadre de son sujet d’étude, à savoir « l’histoire des odeurs et la mémoire des peuples ». Le thème des parfums reviendra d’ailleurs comme un leitmotiv tout au long du film, qui aurait tout à fait pu être une œuvre tournée en odorama ! Les choses ne se passent toutefois pas comme prévu et, peu après son arrivée, la jeune fille, trompée par un chauffeur de taxi, est livrée à un groupe de djihadistes qui la prennent en otage pour obtenir de l’argent de la France. L’histoire nous est racontée tour à tour selon trois perspectives : celle de Lucie, celle de Younes (le chauffeur de taxi en proie à un dilemme moral et que les difficultés économiques contraignent à se faire le complice des islamistes) et celle d’Abou (un djihadiste d’origine française qui va peu à peu être assailli de doutes sur son engagement à mesure que la situation se dégrade).

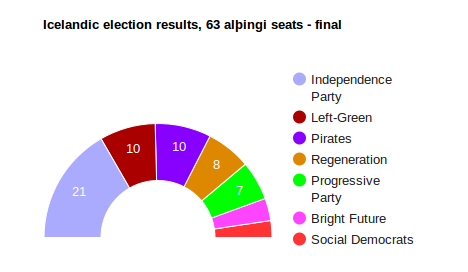

Le parti « rouge-vert » des écologistes de gauche avec 15,9% des voix (+5.1) et 10 sièges (+3) est également un des grands vainqueurs de ce scrutin. Cela explique aussi sans doute la contre-performance des Pirates par rapport aux promesses des sondages. De même les écologistes pro-européens de Vidreisn, nouvelle formation politique, avec 10,5% des voix et 7 sièges, rentrent au parlement où ils y renforcent la gauche. Avec les sociaux-démocrates islandais, en perte de vitesse, n’obtenant que 5,7% des voix (-7,1) et 3 sièges (-6), la gauche et les Pirates réunis n'auraient 30 sièges (sur 63). Mais il s’agirait d’une coalition certes légèrement majoritaire mais très hétéroclite.

Le parti « rouge-vert » des écologistes de gauche avec 15,9% des voix (+5.1) et 10 sièges (+3) est également un des grands vainqueurs de ce scrutin. Cela explique aussi sans doute la contre-performance des Pirates par rapport aux promesses des sondages. De même les écologistes pro-européens de Vidreisn, nouvelle formation politique, avec 10,5% des voix et 7 sièges, rentrent au parlement où ils y renforcent la gauche. Avec les sociaux-démocrates islandais, en perte de vitesse, n’obtenant que 5,7% des voix (-7,1) et 3 sièges (-6), la gauche et les Pirates réunis n'auraient 30 sièges (sur 63). Mais il s’agirait d’une coalition certes légèrement majoritaire mais très hétéroclite.

Question :

Question :

Absolument tous les reproches, et les plus durs, peuvent être faits à François Mitterrand, mais enfin, c’était un assez bon lettré, aimant comme vous le savez passionnément l’œuvre d’Ernst Jünger, qu’il connaissait personnellement. Je me souviens d’avoir lu qu’il reprocha un jour à un certain Alain Juppé qui joue aujourd’hui les revenants arrogants, de ne pas connaître Paul Gadenne. S’il n’y avait qu’Alain Juppé qui ignorât l’auteur de La plage de Scheveningen, l’un des plus beaux et grands romans du siècle passé ! Qui connaît encore, hélas, le profond et tourmenté Paul Gadenne ? Certainement pas le crétin hollandais, dont on se demande même s’il a jamais entendu parler d’un mot aussi bizarre et incongru que celui de « littérature » ! Quoi qu’il en soit, j’ai lu Rebatet jeune, trop jeune peut-être et, comme tant d’autres auteurs, il me faut à présent le relire, alors qu’il semble jouir d’une certaine actualité, du moins éditoriale, qui ne s’est pas encore vraiment étendue à des auteurs comme Brasillach (évoqué par Gadenne, qui fut son condisciple en khâgne, dans le roman que j’ai indiqué, sous les traits d’un personnage du nom d’Hersent), Brasillach dont il faut lire Notre avant-guerre, ou bien le pestiféré Abel Bonnard, dont Les Modérés sont une radiographie de la France politique encore pertinente. Je me souviens en tout cas d’avoir estimé, du haut de mes 14 ou 15 ans, que Les Deux Étendards, roman au titre génial, disséquait la France de l’entre-deux guerres avec une profondeur spirituelle absente des romans de Céline, et ce seul souvenir me donne envie de relire ce roman qui avait la réputation, il n’y a pas si longtemps que cela, d’être maudit. Par ailleurs, j’allais, quelques années plus tard, retrouver le nom de Rebatet sous la plume de George Steiner, qui n’a jamais cessé de clamer son admiration pour ce roman, tout en traitant son auteur de salopard. J’ai d’ailleurs commencé ma relecture des Décombres qui vient d’être réédité, après avoir aussi relu le Rebatet de Pol Vandromme et en faisant un crochet par Les Réprouvés d’Ernst von Salomon, décrivant la nécessité d’une refondation de l’Allemagne humiliée par les sanctions des alliés et rongée par la gangrène communiste que les corps francs tentent de contenir, voire d’éradiquer. Il n’est donc pas étonnant que Lucien Rebatet, de même que d’autres qui ont décrit la complexité d’une époque où la France cherchait une forme de renaissance politique tout autant que sociale, voire spirituelle, intéresse et même fascine de nouveau, y compris les jeunes si on leur apprend encore à lire, maintenant que notre pays traverse une crise qui sera mortelle si aucun sursaut, de réelle profondeur et pas cosmétique, ne le sauve. Et puis, à tout prendre, je préfère un jeune gars un peu borné nourri au petit lait de Charles Maurras, mais qui aura au moins lu, et avec passion, Bloy, Bernanos, Jünger, Von Salomon, Rebatet, Brasillach, Hansum ou Pasolini et quelques autres encore sur lesquels planent de vilains soupçons, plutôt qu’un crétin ripoliné fraîchement hypokhâgneux qui n’aura sucé que les mamelles desséchées de Gérard Genette et de Roland Barthes, l’esprit tout farci des fadaises naturalistes sans style de Maupassant et de Zola, et qui finira sous-pigiste à Télérama ou aux Inrockuptibles, à saluer le gras loukoum à orientalisme germanopratin goncourisé d’un Mathias Enard. La passion, l’excès, le courage, plutôt que ces sépulcres déjà blanchis rêvant carrière et petite épouse sage rencontrée à l’école et qui finira comme eux professeur dans le meilleur des cas, à l’âge où Jean-René Huguenin savait qu’il n’égalerait jamais Rimbaud et Carlo Michelstaedter se tirait une balle dans la tête après avoir écrit le dernier mot de sa Persuasion et la rhétorique !

Absolument tous les reproches, et les plus durs, peuvent être faits à François Mitterrand, mais enfin, c’était un assez bon lettré, aimant comme vous le savez passionnément l’œuvre d’Ernst Jünger, qu’il connaissait personnellement. Je me souviens d’avoir lu qu’il reprocha un jour à un certain Alain Juppé qui joue aujourd’hui les revenants arrogants, de ne pas connaître Paul Gadenne. S’il n’y avait qu’Alain Juppé qui ignorât l’auteur de La plage de Scheveningen, l’un des plus beaux et grands romans du siècle passé ! Qui connaît encore, hélas, le profond et tourmenté Paul Gadenne ? Certainement pas le crétin hollandais, dont on se demande même s’il a jamais entendu parler d’un mot aussi bizarre et incongru que celui de « littérature » ! Quoi qu’il en soit, j’ai lu Rebatet jeune, trop jeune peut-être et, comme tant d’autres auteurs, il me faut à présent le relire, alors qu’il semble jouir d’une certaine actualité, du moins éditoriale, qui ne s’est pas encore vraiment étendue à des auteurs comme Brasillach (évoqué par Gadenne, qui fut son condisciple en khâgne, dans le roman que j’ai indiqué, sous les traits d’un personnage du nom d’Hersent), Brasillach dont il faut lire Notre avant-guerre, ou bien le pestiféré Abel Bonnard, dont Les Modérés sont une radiographie de la France politique encore pertinente. Je me souviens en tout cas d’avoir estimé, du haut de mes 14 ou 15 ans, que Les Deux Étendards, roman au titre génial, disséquait la France de l’entre-deux guerres avec une profondeur spirituelle absente des romans de Céline, et ce seul souvenir me donne envie de relire ce roman qui avait la réputation, il n’y a pas si longtemps que cela, d’être maudit. Par ailleurs, j’allais, quelques années plus tard, retrouver le nom de Rebatet sous la plume de George Steiner, qui n’a jamais cessé de clamer son admiration pour ce roman, tout en traitant son auteur de salopard. J’ai d’ailleurs commencé ma relecture des Décombres qui vient d’être réédité, après avoir aussi relu le Rebatet de Pol Vandromme et en faisant un crochet par Les Réprouvés d’Ernst von Salomon, décrivant la nécessité d’une refondation de l’Allemagne humiliée par les sanctions des alliés et rongée par la gangrène communiste que les corps francs tentent de contenir, voire d’éradiquer. Il n’est donc pas étonnant que Lucien Rebatet, de même que d’autres qui ont décrit la complexité d’une époque où la France cherchait une forme de renaissance politique tout autant que sociale, voire spirituelle, intéresse et même fascine de nouveau, y compris les jeunes si on leur apprend encore à lire, maintenant que notre pays traverse une crise qui sera mortelle si aucun sursaut, de réelle profondeur et pas cosmétique, ne le sauve. Et puis, à tout prendre, je préfère un jeune gars un peu borné nourri au petit lait de Charles Maurras, mais qui aura au moins lu, et avec passion, Bloy, Bernanos, Jünger, Von Salomon, Rebatet, Brasillach, Hansum ou Pasolini et quelques autres encore sur lesquels planent de vilains soupçons, plutôt qu’un crétin ripoliné fraîchement hypokhâgneux qui n’aura sucé que les mamelles desséchées de Gérard Genette et de Roland Barthes, l’esprit tout farci des fadaises naturalistes sans style de Maupassant et de Zola, et qui finira sous-pigiste à Télérama ou aux Inrockuptibles, à saluer le gras loukoum à orientalisme germanopratin goncourisé d’un Mathias Enard. La passion, l’excès, le courage, plutôt que ces sépulcres déjà blanchis rêvant carrière et petite épouse sage rencontrée à l’école et qui finira comme eux professeur dans le meilleur des cas, à l’âge où Jean-René Huguenin savait qu’il n’égalerait jamais Rimbaud et Carlo Michelstaedter se tirait une balle dans la tête après avoir écrit le dernier mot de sa Persuasion et la rhétorique ! Les Hussards sont des auteurs que je connais finalement assez peu, n’ayant lu que quelques ouvrages de Chardonne, Laurent ou Nimier, bien sûr Les Épées mais aussi Le Grand d’Espagne, qui évoque Georges Bernanos. Comme bien d’autres (je songe ainsi à Péguy, transformé, par l’opération du Saint-Esprit sans doute, en auteur et même penseur de droite), ils ont été d’une certaine façon abâtardis, journalisés par tout un tas de leurs épigones plus ou moins inspirés, revendiqués ou pas. D’ici peu, Causeur leur consacrera un dossier, si ce n’est déjà fait, et c’est ainsi qu’ils seront happés et hachés menu, puis accrochés au plafond, au milieu d’autres andouilles d’appellation et d’origine contrôlées comme Philippe Muray, devenu le saint patron de la Réaction puérile à laquelle nous assistons. Très peu pour moi que cet eczéma purement journalistique, que quelques petits Mohicans attendant les Cosaques et une paire de jolies fesses, y compris celles du Saint-Esprit, gratteront en croyant découvrir des cavernes d’originalité. Il me semble, au cas où vous me poseriez cette question, que l’esprit des Hussards a survécu plus qu’il ne survit, car il semble désormais bien mort, le temps où une seule phrase, aiguisée comme le morfil d’une dague, pouvait d’un trait précis clouer une vieille chouette radoteuse. Le dernier rétiaire de ce genre, altier et redoutable, même s’il a parfois trop donné dans un hermétisme littéraire de pacotille, était Dominique de Roux, et un livre tel qu’Immédiatement, publié aujourd’hui, vaudrait à son auteur une bonne quinzaine de procès, et une chasse à l’homme en règle, qu’il eut d’ailleurs à subir de son vivant. Je songe aussi à l’exemple tragique et lumineux de Jean-René Huguenin, mort en 1962 comme Nimier, également dans un accident de voiture. Je songe encore à Guy Dupré, hélas si profondément méconnu voire ignoré par nos élites littéraires ou ce qui en tient lieu, lequel d’ailleurs a écrit un de ses textes si subtils et profondément littéraires sur Sunsiaré de Larcône (recueilli dans Les Manœuvres d’automne), une belle femme que tout Hussard a dû tour à tour envier et maudire au moins une fois !

Les Hussards sont des auteurs que je connais finalement assez peu, n’ayant lu que quelques ouvrages de Chardonne, Laurent ou Nimier, bien sûr Les Épées mais aussi Le Grand d’Espagne, qui évoque Georges Bernanos. Comme bien d’autres (je songe ainsi à Péguy, transformé, par l’opération du Saint-Esprit sans doute, en auteur et même penseur de droite), ils ont été d’une certaine façon abâtardis, journalisés par tout un tas de leurs épigones plus ou moins inspirés, revendiqués ou pas. D’ici peu, Causeur leur consacrera un dossier, si ce n’est déjà fait, et c’est ainsi qu’ils seront happés et hachés menu, puis accrochés au plafond, au milieu d’autres andouilles d’appellation et d’origine contrôlées comme Philippe Muray, devenu le saint patron de la Réaction puérile à laquelle nous assistons. Très peu pour moi que cet eczéma purement journalistique, que quelques petits Mohicans attendant les Cosaques et une paire de jolies fesses, y compris celles du Saint-Esprit, gratteront en croyant découvrir des cavernes d’originalité. Il me semble, au cas où vous me poseriez cette question, que l’esprit des Hussards a survécu plus qu’il ne survit, car il semble désormais bien mort, le temps où une seule phrase, aiguisée comme le morfil d’une dague, pouvait d’un trait précis clouer une vieille chouette radoteuse. Le dernier rétiaire de ce genre, altier et redoutable, même s’il a parfois trop donné dans un hermétisme littéraire de pacotille, était Dominique de Roux, et un livre tel qu’Immédiatement, publié aujourd’hui, vaudrait à son auteur une bonne quinzaine de procès, et une chasse à l’homme en règle, qu’il eut d’ailleurs à subir de son vivant. Je songe aussi à l’exemple tragique et lumineux de Jean-René Huguenin, mort en 1962 comme Nimier, également dans un accident de voiture. Je songe encore à Guy Dupré, hélas si profondément méconnu voire ignoré par nos élites littéraires ou ce qui en tient lieu, lequel d’ailleurs a écrit un de ses textes si subtils et profondément littéraires sur Sunsiaré de Larcône (recueilli dans Les Manœuvres d’automne), une belle femme que tout Hussard a dû tour à tour envier et maudire au moins une fois ! Mon intérêt pour la figuration littéraire du démoniaque n’a pu être que conforté par la découverte de l’œuvre romanesque de Georges Bernanos, qui devait culminer par la lecture de Monsieur Ouine, réputé, à juste titre, comme étant le roman le plus difficile de l’auteur et qui, du diable et du démoniaque, donne une peinture absolument fascinante. J’ai tenté d’éclairer de plusieurs façons ce roman, par exemple en le rapprochant de l’hermétisme démoniaque tel que le développe Kierkegaard ou bien en en proposant une lecture comparée avec Cœur des ténèbres de Joseph Conrad, par le biais de l’étude de la voix des personnages principaux, Kurtz et l’ancien professeur de langues, tous deux maîtres d’un langage dévoyé. Bien évidemment, aucune mention de ces travaux (et d’autres, comme l’influence plus ou moins souterraine d’Arthur Machen sur Sous le soleil de Satan, par le biais de la si belle traduction que Paul-Jean Toulet donna du Grand Dieu Pan) dans la nouvelle édition des œuvres romanesques de Bernanos en Pléiade mais, comme c’est Monique Gosselin-Noat qui a été chargée par Max Milner de l’édition de Monsieur Ouine, il ne fallait certes pas s’attendre à ce qu’elle mentionne autre chose que ses petites fadaises universitaires !

Mon intérêt pour la figuration littéraire du démoniaque n’a pu être que conforté par la découverte de l’œuvre romanesque de Georges Bernanos, qui devait culminer par la lecture de Monsieur Ouine, réputé, à juste titre, comme étant le roman le plus difficile de l’auteur et qui, du diable et du démoniaque, donne une peinture absolument fascinante. J’ai tenté d’éclairer de plusieurs façons ce roman, par exemple en le rapprochant de l’hermétisme démoniaque tel que le développe Kierkegaard ou bien en en proposant une lecture comparée avec Cœur des ténèbres de Joseph Conrad, par le biais de l’étude de la voix des personnages principaux, Kurtz et l’ancien professeur de langues, tous deux maîtres d’un langage dévoyé. Bien évidemment, aucune mention de ces travaux (et d’autres, comme l’influence plus ou moins souterraine d’Arthur Machen sur Sous le soleil de Satan, par le biais de la si belle traduction que Paul-Jean Toulet donna du Grand Dieu Pan) dans la nouvelle édition des œuvres romanesques de Bernanos en Pléiade mais, comme c’est Monique Gosselin-Noat qui a été chargée par Max Milner de l’édition de Monsieur Ouine, il ne fallait certes pas s’attendre à ce qu’elle mentionne autre chose que ses petites fadaises universitaires ! Tenez, j’ai récemment pointé, dans un long article fouillé, les très étranges coïncidences, selon le terme pudique employé par ces temps de judiciarisation de la vie française, entre Soumission de Michel Houellebecq et le roman d’un auteur bien moins connu que ce dernier,

Tenez, j’ai récemment pointé, dans un long article fouillé, les très étranges coïncidences, selon le terme pudique employé par ces temps de judiciarisation de la vie française, entre Soumission de Michel Houellebecq et le roman d’un auteur bien moins connu que ce dernier,