samedi, 30 avril 2022

Sondagite aiguë

Sondagite aiguë

par Georges FELTIN-TRACOL

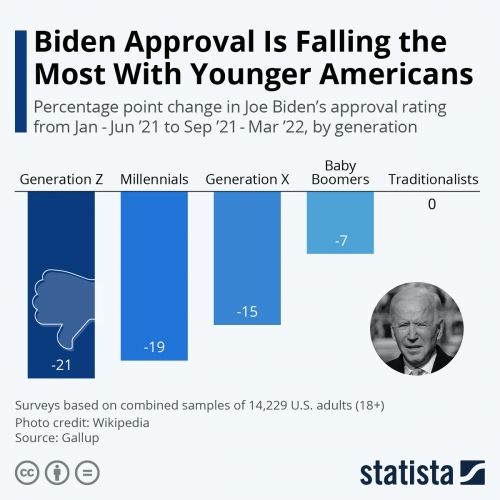

Les régimes pseudo-démocratiques d’Occident se complaisent volontiers dans un mal moderne venu d’outre-Atlantique : la « sondagite aiguë ». Certes, il ne s’agit pas d’une nouvelle épidémie virale ou d’une infection microbienne jusque-là inconnue. La « sondagite aiguë » désigne l’emploi compulsif et incessant des enquêtes d’opinion et des sondages par les gouvernements, les médiats et les formations politiques. La récente élection présidentielle française et les législatives à venir témoignent de leur grande nocivité.

Politologues et journalistes s’accordent sur les résultats du premier tour, le 10 avril 2022: les trois candidats qui franchissent la barre des 20 % ont bénéficié dans les derniers jours d’un vote utile. Les électeurs ont choisi un candidat non pas en fonction de son programme, de ses convictions, de sa personnalité, mais en suivant les intentions de vote publiées tous les jours avant les quarante-huit heures fatidiques de réserve électorale obligatoire.

C’est à la présidentielle de 2002 que s’est installée cette vilaine habitude de sondagite permanente. Auparavant, entre 1965 et 1995, les plus anciens auditeurs s’en souviennent peut-être, les quinze jours de la campagne officielle s’effectuaient en l’absence de tout sondage. L’incertitude dominait les derniers jours. Ainsi personne ne vit-il les 14,39 % en 1988 et les 15 % en 1995 de Jean-Marie Le Pen. Toujours en 1995, les sondages alors confidentiels pronostiquaient un duel entre Édouard Balladur et Jacques Chirac. C’est le candidat socialiste Lionel Jospin qui arriva en tête au soir du 23 avril avec 23,30 %.

La publication répétée des sondages jusqu’à l’ultime instant autorisé transforme les citoyens en véritables « parieurs » politiques, en « turfistes » électoraux qui misent non point sur les meilleurs chevaux de course, mais sur le candidat le plus apte à gagner. Cette pratique marque en matière politico-électorale le passage de l’électeur en consommateur d’ailleurs vite dépité par son choix.

La propension sondagière commence en France en 1965 au moment de la première élection présidentielle au suffrage universel direct de la Ve République. L’atlantiste libéral Jean Lecanuet mène une campagne inspirée de l’exemple étatsunien. Surnommé « Monsieur Dents blanches », le maire centriste de Rouen s’inspire du candidat Kennedy et bénéficie des conseils avisés du publicitaire Michel Bongrand qui inaugure dans l’Hexagone les méthodes de mercatique politique. Couplée aux premiers sondages politiques, la persuasion quasi-commerciale de segments socio-professionnels particuliers assure à Jean Lecanuet une troisième place, 15,57 % des suffrages, qui met en ballottage le général De Gaulle trop sûr de lui-même, et assèche le candidat national, Jean-Louis Tixier-Vignancour, qui plafonne à 5,20 %.

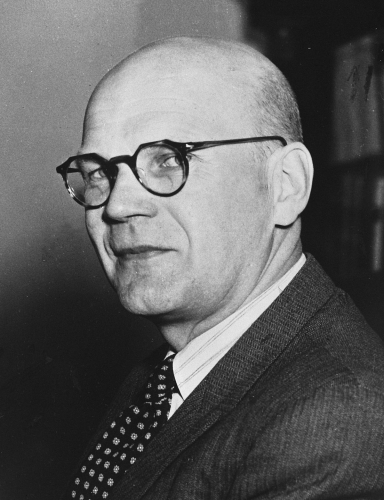

Michel Bongrand (photo) est le lointain ancêtre des spin doctors anglo-saxons, capables de vendre des tonnes de sable aux habitants du Sahara par une narration médiatique sophistiquée. En Russie, leurs équivalents s’activent autour des polittekhnologui (ou « technologies politiques »). Ce terme regroupe les démarches de lobbying, les relations publiques, voire des actions compromettantes si possibles filmées. Toutes travaillent l’électorat sous l’impulsion des professionnels de l’information, de l’influence subliminale, de la manipulation factuelle et de la désinformation.

Le recours massif aux sondages n’est pas anecdotique. Avant la campagne officielle qui impose une stricte égalité du temps d’antenne des candidats, les semaines qui précédent cette phase déterminante appliquent une équité entre les candidats. Outre les résultats électoraux antérieurs récents, entrent dans la prise en compte les tendances générales indiquées dans les sondages. Cette procédure entérinée par les autorités de l’audio-visuel accentue l’invisibilité des « petits candidats » qui, écartés des émissions grand public, restent inaperçus aux yeux du public. Cette absence de visibilité rend plus incertaine encore la collecte des parrainages comme Florian Philippot a pu l’observer récemment.

L’importance accordée aux sondages permet enfin aux plumitifs du Système de relativiser certaines performances obtenues. Au lendemain du premier tour, les 7,07 % d’Éric Zemmour déroutent ses sympathisants. Les commentateurs ne se privent pas de comparer ce résultat effectif avec les sondages flatteurs d’octobre – novembre 2021 qui le propulsaient au second tour face à Emmanuel Macron. Or un sondage n’est que la radiographie de l’opinion publique à partir d’un panel sociologique scientifiquement constitué à un instant T. Ses données demeurent virtuelles, liquides qui ne peuvent pas être confrontées avec le résultat définitif. Réunir 2.485.226 voix pour un essayiste candidat néophyte est un exploit impossible à minimiser, surtout quand il s’accompagne d’un écroulement parallèle des deux partis qui ont dominé la Ve République de 1958 à 2017 !

Quitte à se mettre à dos les instituts de sondage et les étudiants en sciences politiques ou en sociologie qui y exercent de petits boulots, il serait temps d’interdire strictement la réalisation et la publication de tout sondage politique au minimum quinze jours avant le premier tour et au maximum un à deux mois auparavant au nom de la salubrité publique et de l’hygiène mentale du corps électoral. On notera que l’électeur occidental n’adhère plus à un projet particulier; il préfère rejeter celui des autres. Il participe à un jeu de massacre qui, au final, le conduit à un abattoir symbolique. Les sondages incitent à un comportement moutonnier panurgique collectif.

Georges Feltin-Tracol

- « Vigie d’un monde en ébullition », n° 30, mise en ligne le 26 avril 2022 sur Radio Méridien Zéro.

21:15 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : sondages, france, actualité, présidentielles françaises 2022, europe, affaires européennes |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

vendredi, 29 avril 2022

Où l'Occident trouvera-t-il des roubles?

Où l'Occident trouvera-t-il des roubles?

par Luciano Lago

Source: https://www.ideeazione.com/loccidente-dove-trovera-i-rubli/

Poutine a ordonné que le marché monétaire national de la Russie soit préparé au passage au règlement en roubles des livraisons à l'exportation, pour l'instant, notamment du gaz naturel. Cette demande devient urgente car les banques des "pays hostiles" (un terme technique qui inclut l'UE et la plupart des pays anglophones) retardent délibérément et volontairement les paiements pour l'énergie russe. Par conséquent, les livraisons sont désormais effectuées à crédit - un crédit basé sur le rouble !

Entre-temps, le taux de référence de la banque centrale russe est passé à 17%, contre 20% précédemment, mais quand même ! Il semble que quelqu'un de pas très intelligent fasse tout pour faire grimper les prix de l'énergie. Entre-temps, les paiements reçus pour les exportations de pétrole et de gaz ont été réduits de moitié, ce qui rend probable que ces mêmes exportations (vers des "pays hostiles") seront également réduites de moitié. À ce stade, certains historiens pourraient sortir de vieux livres poussiéreux et prétendre que ce genre de politique commerciale folle était la cause de la Grande Dépression. Je ne suis pas d'accord et je l'appelle l'effondrement des entreprises, qui suit l'effondrement financier avec sa perte d'accès au crédit causée par un risque de contrepartie excessif.

Poutine aimerait que ce problème soit résolu. Il veut que l'Europe soit maintenue en vie car la Russie n'a pas besoin d'un énorme cadavre en décomposition à sa frontière occidentale. Le problème avec le décret de Poutine est que les banques russes feront office d'agents de change dans le règlement du programme "marchandises contre roubles" et que les transactions de conversion auront lieu sur le marché des devises de la Bourse de Moscou au sein du système financier russe, et que ce système connaît une grave pénurie d'acheteurs de devises étrangères.

Poutine n'est pas un magicien, et il ne peut pas générer à partir de rien une armée de zombies qui voudront emprunter des roubles et acheter avec eux des dollars et des euros qu'il n'y a aucun moyen d'investir de manière rentable pour rembourser les intérêts de la dette libellée en roubles; pas avec une inflation à deux chiffres dans la zone euro et la zone dollar; pas avec un taux d'intérêt d'au moins 17% sur le rouble. Sauf une, sur laquelle je reviendrai plus tard.

Si ce ne sont pas les zombies, alors qui élargira ses positions en dollars et en euros à une échelle aussi gigantesque?

Des importateurs russes? Non, les importations représentent la moitié des exportations, sans parler des problèmes logistiques et contractuels dus aux sanctions.

Le peuple russe? Certainement pas! La mode consistant à conserver un stock de billets de 100 dollars sous le matelas a disparu depuis longtemps, tout comme celle consistant à conserver des comptes en dollars dans les banques russes. Tout le paradigme monétaire a changé et il n'y a pas assez de monnaie libre parmi la population russe pour absorber les flux d'exportation.

Des entreprises russes ? Parmi eux, seuls les exportateurs disposent de ressources importantes, mais leur faire accepter des dollars ou des euros les ramène à la case départ et ne fait qu'exacerber leur problème en les obligeant à vendre 80 % de ces dollars et euros en roubles. Et le problème est encore pire pour les exportateurs russes, qui doivent maintenant essentiellement vendre 100 % de leurs revenus en dollars et en euros pour des roubles.

Les banques russes? C'est une possibilité ce mois-ci, mais pas dans les mois à venir. Les banques servent les intérêts de leurs clients et ceux-ci, ayant été coupés du système financier occidental, n'ont plus besoin de dollars ou d'euros. Et comme ils ont eux-mêmes été coupés du système financier occidental, ils n'ont pas non plus besoin de ces monnaies. Ils liquident leurs actifs en dollars et en euros.

Oh, et enfin, les étrangers n'ont pas accès au marché des changes russe. Cela rend les choses vraiment simples, n'est-ce pas?

Il ne reste plus que la banque centrale russe et le gouvernement russe qui la possède et l'exploite. Alors qu'auparavant ils se contentaient d'accumuler des réserves en dollars et en euros, la définition des réserves a été modifiée pour exclure ces deux éléments. Si une accumulation de réserves de change devait avoir lieu maintenant, ce serait en yuan, et alors tous ces roubles excédentaires passeraient directement des mains des acheteurs d'énergie des "nations hostiles" aux mains amicales des exportateurs chinois.

On pourrait penser que les Chinois polis seraient prêts à accepter des dollars et des euros en échange de leurs exportations vers la Russie, ce qui leur permettrait de gagner des roubles en utilisant ces deux monnaies. Malheureusement non, la Chine et la Russie ont passé des accords pour transférer leurs échanges commerciaux vers le rouble et le yuan, excluant spécifiquement le dollar.

J'ai bien peur de ne pas avoir d'idées brillantes à proposer pour résoudre ce problème, comme l'a ordonné Poutine. Il y a cependant une idée. Il est possible d'obtenir des crédits en roubles très bon marché dans le but de remplacer les importations. Le plan consiste donc à emprunter des roubles, à les utiliser pour acheter des dollars ou des euros, puis à utiliser ces dollars ou ces euros pour acheter, emballer et expédier en Russie des usines et des équipements occidentaux capables de fabriquer des produits pour lesquels il existe une demande en Russie et dans les pays amis de la Russie.

Bien sûr, les gouvernements occidentaux tenteront très probablement de bloquer ce plan. Ils n'ont plus beaucoup d'occasions de se tirer une balle dans le pied, mais ils vont certainement continuer à essayer. Et la Russie se retrouvera avec un énorme cadavre en décomposition à ses frontières occidentales. J'espère que quelqu'un trouvera le moyen d'exécuter l'ordre de Poutine, mais je n'ai aucune idée de ce que cela pourrait être.

26 avril 2022

18:26 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes, Economie | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, europe, russie, occident, rouble, politique internationale, affaires européennes |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Pourquoi l'Occident déteste la Russie et Poutine

Pourquoi l'Occident déteste la Russie et Poutine

par Fabrizio Marchi

Source : Fabrizio Marchi & https://www.ariannaeditrice.it/articoli/perche-l-occidente-odia-la-russia-e-putin

Bien que cela puisse ressembler à un fantasme politique, surtout pour ceux qui ne sont pas impliqués dans la politique internationale, il est important de souligner que l'objectif stratégique de l'offensive globale américaine (lire, entre autres, l'expansion de l'OTAN à l'Est), est la Chine, et non la Russie.

L'affaiblissement, voire la déstabilisation de la Russie à moyen-long terme n'est "que" (avec beaucoup de guillemets...) une étape intermédiaire, même si elle est d'une importance énorme, pour isoler la Chine, le véritable et plus important concurrent des Américains. Tout reste à vérifier, bien sûr, pour savoir si cela est possible, mais à mon avis, telle est bien l'intention.

Les États-Unis cherchent à prolonger le conflit en Ukraine le plus longtemps possible, voire à le rendre permanent. Ils espèrent ainsi saigner la Russie, tant sur le plan militaire que, surtout, sur le plan économique, et l'user psychologiquement au fil du temps, en sapant sa cohésion interne. À moyen terme, la guerre pourrait renforcer le leadership de Poutine, et c'est déjà le cas, mais à long terme, elle pourrait peut-être l'affaiblir. Après tout, rester embourbé dans une guerre à long terme peut être, et a été, déstabilisant pour tout le monde. Pensez au Vietnam pour les États-Unis et à l'Afghanistan pour l'Amérique et l'Union soviétique, pour ne citer que quelques exemples bien connus. Et quelle que soit la solidité du leadership de Poutine, nous ne pouvons pas exclure a priori qu'il puisse être affaibli en interne au fil du temps. Dans quelle mesure et si cela est possible, comme je l'ai dit, est une autre question, mais je crois que la stratégie du Pentagone est la suivante.

Immédiatement après l'effondrement de l'URSS (mais la désintégration avait déjà commencé depuis un certain temps), la Russie a été réduite à l'état de colonie, un pays disposant d'un énorme réservoir de matières premières à piller et d'une grande masse de main-d'œuvre bon marché à la disposition des multinationales et des entreprises occidentales, ainsi que d'un gouvernement d'hommes d'affaires sans scrupules, de mèche avec la mafia et dirigé par une marionnette ivre au service des États-Unis. Ils étaient convaincus qu'ils avaient le monde entre leurs mains. Et c'était leur plus grande erreur. Une erreur qu'ils ont en fait souvent commise au cours des trente dernières années. Ils ont été littéralement délogés par la croissance économique impétueuse, voire inquiétante, de la Chine et n'ont pas pensé que la Russie pouvait se relever et retrouver sa force, son centre de gravité, son identité, qui est celle d'un grand pays, avec une grande histoire, une grande culture et un grand peuple qui ne peut accepter d'être réduit à une colonie de l'Occident.

Qu'on le veuille ou non (cela n'a absolument rien à voir avec la compréhension des choses), Poutine était l'homme qui incarnait cette renaissance. Et c'est précisément cela que l'Occident ne lui pardonne pas. Parce qu'il leur a enlevé le grand jouet qu'ils pensaient avoir entre les mains et, ce faisant, leur a enlevé le rêve - qui semblait avoir été réalisé - de pouvoir dominer la planète entière.

Que la croisade anti-russe se fasse pour défendre les valeurs occidentales, la liberté, les droits civils et la démocratie, c'est évident, mais c'est du bavardage, de la propagande des plus évidentes, de la soupe pour les naïfs (je ne veux pas m'y frotter...). L'Occident fait et a fait des affaires, a soutenu, financé, armé et souvent créé les dictatures les plus féroces dans le monde entier (tout comme il n'hésite pas aujourd'hui à anoblir la pire racaille nazie-fasciste jamais vue en Europe depuis la fin de la Seconde Guerre mondiale), et encore moins si le problème peut être les droits et la démocratie. Si Putin était à votre service, vous pourriez aussi bien manger littéralement de la chair de petit enfant au petit déjeuner et personne ne s'en soucierait le moins du monde et tout le monde trouverait même un moyen de le dissimuler.

Affaiblir, réduire radicalement ou même déstabiliser la Russie et installer un gouvernement complaisant signifierait, comme je l'ai dit, isoler la Chine. Pensons aujourd'hui à l'Inde, un pays formellement placé dans la sphère d'influence occidentale, mais en fait non homogène avec cette même sphère, pour des raisons géographiques évidentes et donc économiques et commerciales. Avec la disparition de la Russie, l'autre principal bastion, outre la Chine, du bloc (euro-asiatique), l'Inde serait inévitablement aspirée dans la sphère d'influence occidentale, et peut-être aussi le Pakistan, un allié des États-Unis jusqu'à il y a tout juste un an ou deux.

Il s'agit évidemment d'une stratégie et d'un projet très ambitieux avec lesquels les Américains pourraient jouer à moyen et long terme. D'autre part, s'ils ne parviennent pas à briser d'une manière ou d'une autre le lien entre la Russie et la Chine, c'est-à-dire l'axe central du bloc asiatique (possible mais pas encore complètement homogène), les choses pourraient se gâter pour les États-Unis et le bloc occidental.

C'est pourquoi la crise actuelle est certainement la plus grave et la plus inquiétante depuis la fin de la Seconde Guerre mondiale. Objectivement, nous ne sommes pas en mesure de prévoir les évolutions et, surtout, les résultats potentiellement dramatiques.

18:15 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : russie, chine, états-unis, occident, vladimir poutine |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Elections françaises: le peuple dit "non", les élites disent "oui" à Macron

Elections françaises: le peuple dit "non", les élites disent "oui" à Macron

par Daria Platonova Douguina

Source: https://www.ideeazione.com/elezioni-francesi-il-popolo-dice-no-le-elite-dicono-si-a-macron/

Au second tour, Emmanuel Macron a obtenu 58,55% des voix (résultats fournis par le ministère français de l'Intérieur après traitement de 100% des bulletins de vote). La première soirée après l'élection du président pour un second mandat a déjà été marquée par des manifestations de grande ampleur contre le "macronisme" et le libéralisme. Les gilets jaunes, des éléments de la gauche et de la droite sont descendus dans la rue. Philippe Poutou, le leader du parti anticapitaliste, a appelé au renversement de Macron. Et les leaders de l'opposition (Le Pen, Zemmour, Mélenchon), dont l'électorat cumulé dépasse 50% de la population française, ont déclaré que les élections ne sont pas terminées, et que le troisième tour sera les élections législatives qui auront lieu en juin. Macron risque de ne pas obtenir de majorité parlementaire. Cela est fortement influencé par l'échec de sa politique quinquennale, surnommée le "Macronisme", qui a conduit le parti de Macron à ne remporter aucune des 13 régions lors des élections régionales de 2021.

Philippe Poutou.

Le fait que les prochaines années seront turbulentes a également été noté par le président nouvellement élu lui-même. "Un second mandat ne sera pas turbulent, mais il sera historique pour la France", a déclaré M. Macron, lors d'un meeting de victoire. La France risque d'être confrontée à une période d'instabilité, et la page s'est ouverte pour un quinquennat plus défiant (ou même un septennat, dans le cas de la réforme constitutionnelle de Macron visant à prolonger le mandat présidentiel). Le pays entre dans une période de turbulences politiques et les slogans des manifestations d'hier, avec le mot "Révolution", suggèrent de possibles changements radicaux à venir.

Dans le même temps, trois grands blocs politiques ont émergé, dont deux représentent les intérêts du peuple (Le Pen et Mélenchon) et un, Macron, les intérêts des élites transnationales orientées vers un agenda mondialiste. Le résultat de Le Pen est en effet impressionnant: par rapport à 2017 (où l'écart était de 33%), le tableau actuel montre que ses thèses (critique de l'immigration, de l'OTAN, du mondialisme, du capitalisme) reflètent la volonté de la moitié des Français.

Le think tank français Strategika note que "les situations des élections présidentielles de 2017 et de 2022 sont très différentes. En 2017, il y a eu une confrontation entre le candidat Macron, présenté à l'époque par tous les médias et le système politique comme "nouveau", et Marine Le Pen, qui portait en quelque sorte le "poids" du passé (du passé de son parti). Il y avait une illusion que le monde politique vermoulu, contre lequel Macron s'est positionné comme une fausse nouveauté sans précédent, allait soudainement exploser et résoudre des décennies de problèmes accumulés". Toutefois, selon l'auteur de Strategika, en 2022, la situation a radicalement changé: "En 2022, un autre Macron est apparu - avec une crise économique massive à son actif et des politiques néolibérales qui ont eu un impact négatif sur le peuple français et la cohésion sociale du pays, ainsi qu'une série d'échecs en matière de politique intérieure et extérieure, notamment :

- la répression sanglante des "gilets jaunes" ;

- une gestion autoritaire et inadéquate de la crise sanitaire ("covidisme") ;

- le déclin de la démocratie et de la liberté d'expression dans le pays ;

- la dégradation de la situation migratoire dans le pays (un épisode récent hautement symbolique de l'état de guerre civile rampante de la France a été l'assassinat en prison du militant nationaliste corse Ivan Colonna par un djihadiste. Sans parler de l'hypothèse de l'exécution éventuelle donc d'un meurtre sur commande) ;

- échec au Mali et perte d'influence sur le continent africain ;

- l'annulation des contrats de sous-marins avec l'Australie ;

- l'échec du processus de paix entre Moscou et Kiev".

La crédibilité de Macron a également été ébranlée par une importante affaire McKinsey: "Macron a effectivement placé le pays sous un contrôle externe: le Sénat français a constaté que la France perdait sa souveraineté dans la sphère législative".

Strategika note que "outre la montée en popularité de Marine Le Pen (également causée par la présence dans son projet d'un certain nombre d'éléments de politique socio-économique: retraite à 60 ans, réductions d'impôts, accent mis sur le pouvoir d'achat, etc.), on a assisté à un renforcement de la position de l'homme politique de gauche Jean-Luc Mélenchon. Le point commun des deux candidats est qu'ils se concentrent davantage sur les stratégies visant à résoudre la crise économique actuelle en France et qu'ils envisagent des modèles pour introduire une régulation étatique partielle dans certains secteurs de l'économie dans la période d'après-crise.

Que réserve l'avenir à la France? Devons-nous nous attendre à des changements radicaux? Apparemment, oui. La victoire de Macron hier a ouvert une boîte de Pandore. Le peuple français, sensible à la trahison et à la déloyauté, ne pardonnera pas à un président responsable d'une crise d'une telle ampleur. Les sanctions anti-russes ont touché les cordons de la bourse des Français, beaucoup admettant qu'il est plus coûteux de se déplacer pour aller travailler que de rester au chômage chez soi. La politique étrangère de Macron, que ce soit en Afrique ou en Ukraine, a soulevé des questions non seulement parmi les citoyens ordinaires ou les politiciens, mais aussi parmi les militaires. L'insatisfaction à l'égard de Macron est croissante. Et les lettres sur les pancartes des manifestants deviennent plus vives : "Révolution. Renversons le régime libéral".

27 avril 2022

17:56 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : france, europe, affaires européennes, emmanuel macron, présidentielles françaises 2022 |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 28 avril 2022

Langage clair à la télévision russe: "Les Allemands sont de la chair à canon dans la guerre économique"

Langage clair à la télévision russe: "Les Allemands sont de la chair à canon dans la guerre économique"

Source: https://www.compact-online.de/klartext-im-russischen-fernsehen-deutsche-sind-kanonenfutter-im-wirtschaftskrieg/?mc_cid=3b95b79c94&mc_eid=128c71e308

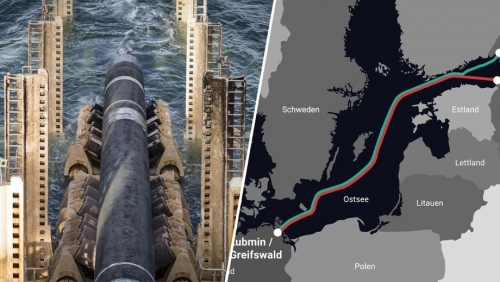

Les sanctions contre la Russie nuisent énormément à l'UE, mais Bruxelles travaille déjà sur le sixième paquet de sanctions. L'économie allemande, en particulier, ne doit plus servir que de chair à canon dans la guerre économique.

par Thomas Röper

La pression monte au sein de l'UE pour que le pétrole et le gaz russes soient également sanctionnés. En outre, il n'y a pas encore d'accord sur l'opportunité de répondre aux exigences russes de payer le gaz en roubles. La Commission européenne, du moins, a déjà fait savoir qu'elle considérait qu'accepter les conditions russes constituait une violation des sanctions de l'UE à l'encontre de la Russie. Dans la revue hebdomadaire d'actualité de la télévision russe, le correspondant russe en Allemagne a énuméré sans ménagement les problèmes actuels de l'Allemagne dans ce contexte de sanctions. Comme il est toujours intéressant de voir comment la Russie rend compte de la situation politique en Allemagne, j'ai traduit le reportage de la télévision russe.

Début de la traduction :

Les Européens hésitent toujours à payer le gaz russe en roubles. Ils sont trop occupés à inventer un nouveau paquet de sanctions, le sixième, contre la Russie. Même les protestations, l'appauvrissement de leur propre population, la hausse vertigineuse des prix du chauffage, de l'essence et de la nourriture ne les arrêtent pas.

Pas de rouble, pas de gaz

Moscou a déclaré sans ambages: si le paiement n'est pas effectué en roubles, il n'y aura pas de gaz. Jusqu'à présent, seuls quelques pays européens ont accepté de payer le gaz en roubles et de ne pas détruire leur économie. Il s'agit de la Hongrie, de la Bulgarie, de la Moldavie, de la Serbie et de l'Arménie.

Le président allemand Frank-Walter Steinmeier (SPD) tolère jusqu'à présent les insultes de l'ambassadeur ukrainien Andrej Melnyk et garde un calme stoïque.

Pourquoi Steinmeier a-t-il été insulté de la sorte? Depuis mardi soir, lorsqu'il a été annoncé que le président allemand ne pourrait pas se rendre à Kiev, les hommes politiques et les médias allemands analysent les raisons de cette démarche diplomatique. Steinmeier lui-même ne s'est pas exprimé à ce sujet, se limitant aux faits. Il s'est exprimé ainsi :

"Mon collègue et ami, le président polonais Duda, a proposé l'autre jour que nous visitions Kiev avec les présidents de Lettonie, de Lituanie et d'Estonie et que nous envoyions un message de solidarité européenne à l'Ukraine. J'étais prêt à le faire, mais apparemment, je dois prendre acte du fait que ce n'était pas dans l'esprit de Kiev".

En quoi le parrain de l'actuel régime ukrainien a-t-il contrarié ses protégés ? On s'est souvenu du soutien de Steinmeier au Nord Stream 2, de ses contacts avec Moscou et de la formule Steinmeier, de son nom, pour appliquer les accords de Minsk, détestés par Kiev.

"Une insulte qui n'aide aucune partie"

Même le président de la CDU, Friedrich Merz, s'est exprimé :

"J'interprète cette insulte, qui a un arrière-plan politico-historique, comme une réaction émotionnelle des dirigeants ukrainiens qui n'aide aucune partie".

D'autre part, Zelensky n'aurait guère osé insulter l'Allemagne sans consulter - directement ou indirectement - Washington, comme le montre la participation de la Pologne à la provocation. Et bien sûr, la véritable cible n'était pas Steinmeier, mais son camarade de parti, Olaf Scholz. Le chancelier allemand ne veut pas partir à la guerre et, si l'on en croit le diplomate en chef de l'UE, M. Borrell, l'Europe définit le processus dans lequel elle est engagée en Ukraine comme une guerre pour elle-même, sans euphémisme ni demi-teinte.

La rébellion des amis des armes

Le premier reproche fait à Scholz est de ne pas vouloir envoyer d'armes lourdes en Ukraine. Le groupe Reinmetall a décidé de se faire un peu d'argent supplémentaire et a rendu un mauvais service au chancelier en annonçant au monde entier qu'il avait en stock cinq douzaines de chars Leopard 1 obsolètes et une soixantaine de véhicules de combat d'infanterie Marder, eux aussi très anciens, et que ces équipements pouvaient encore être utilisés. Cette nouvelle a provoqué un grand émoi parmi les partenaires de la coalition qui demandent à Scholz de donner son feu vert à ces livraisons.

Le magazine Der Spiegel a fait remarquer ce qui suit :

"Le chancelier est de plus en plus sous pression - à Bruxelles et à Berlin - en raison de sa politique réservée à l'égard de l'Ukraine. Une rébellion a éclaté au sein de la coalition. L'incompréhension grandit dans les rangs des partenaires du chef de gouvernement silencieux et extrêmement faible".

Et Anton Hofreiter, président de la commission des affaires européennes au Bundestag, a fait remarquer :

"Nous ternissons notre réputation aux yeux de tous nos voisins. Nous devons enfin commencer à fournir à l'Ukraine ce dont elle a besoin, y compris des armes lourdes. Et l'Allemagne doit cesser de bloquer l'embargo énergétique, notamment sur le pétrole et le charbon".

"Une zone d'exclusion aérienne franchirait la ligne rouge"

Les Verts allemands ont été si actifs qu'au cours de la semaine, des rumeurs ont effectivement circulé selon lesquelles l'Allemagne était sur le point d'envoyer du matériel dans le Donbass, d'autant plus que des convois militaires se dirigeaient effectivement quelque part vers l'est. Le gouverneur de la région de Mykolaïv a tweeté avec excitation que des chars allemands allaient à nouveau traverser l'Ukraine et tirer sur les Russes. Mais la rumeur n'a pas été confirmée: les images qui ont tant inspiré l'homme politique ukrainien ont apparemment donné au chancelier un sentiment si sombre qu'il a pour l'instant émis un "non" ferme.

Olaf Scholz a en revanche souligné :

"Permettez-moi de le dire encore une fois très clairement. Je suis impressionné par le nombre de personnes qui parviennent à googler rapidement quelque chose et à devenir immédiatement des experts en armes. Bien sûr, dans une telle situation, il y aura toujours quelqu'un pour dire: je veux que les événements se déroulent de cette manière. Mais je voudrais dire à certains de ces garçons et filles: je gouverne le pays précisément parce que je ne fais pas les choses comme vous le voudriez".

Il est clair que par "garçon", Scholz entend le député Hofreiter. Mais par "fille", voulait-il évoquer la ministre des Affaires étrangères Baerbock ? D'ailleurs, tous les Verts ne sont pas contre Scholz. Son allié inattendu sur la question de la livraison d'armes lourdes était l'un de leurs leaders, le ministre de l'Économie Habeck. Comme on pouvait s'y attendre, le respecté ministre-président chrétien-démocrate de Saxe, Michael Kretschmer, s'est également rangé du côté de Scholz.

Il a déclaré :

"Nous franchirions une limite si nous fournissions des chars ou des avions, ou même si nous établissions une zone d'exclusion aérienne. Cette ligne doit être maintenue".

Aller en Biélorussie pour faire le plein

Une concession au "parti de la guerre" a été la décision de Scholz d'augmenter immédiatement les dépenses de défense de deux milliards d'euros - dont une grande partie pour l'achat d'armes pour l'armée ukrainienne, qui ne nécessitent pas une longue formation. Cependant, pour satisfaire la deuxième exigence, M. Scholz a besoin de beaucoup plus d'argent et surtout de ce dont il dispose le moins - du temps. Les partenaires demandent un embargo sur l'énergie. La décision a été prise pour le charbon - les importations doivent cesser à la mi-août - mais comment vivre sans pétrole russe ?

Le ministre lituanien des Affaires étrangères, Gabrielius Landsbergis, a quant à lui déclaré:

"Nous commençons maintenant à travailler sur le sixième paquet de sanctions. Avec des options sur le pétrole. Cela signifie que nous avons déjà commencé à travailler pour parvenir à un consensus, et j'espère que cette fois-ci, nous y arriverons".

Rien que des mots

En tout cas, cela va marcher. En fait, tout a déjà fonctionné dans le pays dont la diplomatie est dirigée par M. Landsbergis, sauf qu'on n'entend plus parler de l'industrie lituanienne depuis longtemps et que les citoyens vont faire le plein en Biélorussie.

On peut dire que l'Allemagne, son économie et ses ménages, n'apprécieront pas une telle victoire sur les Russes. De plus, l'OPEP a fortement déçu cette semaine; l'Organisation des pays exportateurs de pétrole ne sera pas en mesure de compenser le retrait de la Russie du marché et l'agence de notation Moody's prévoit que, dans ce cas, le prix du pétrole atteindra immédiatement 160 dollars le baril. Berlin veut élaborer une stratégie progressive de sortie du pétrole russe, mais ce ne sont pour l'instant que des mots.

La situation sur le marché du gaz est encore plus incertaine et menace de diviser l'UE - la date limite pour le passage au rouble approche. La Commission européenne a émis cette semaine un avis selon lequel cela serait contraire à la politique de sanctions de l'UE, qui vise à dévaluer la monnaie russe. On ne peut que constater: oui, l'UE a un gros problème avec cette partie des sanctions.

Ainsi, le chancelier autrichien Karl Nehammer a déclaré :

"L'Autriche n'est pas seule à s'opposer à l'embargo sur le gaz. L'Allemagne, la Hongrie et d'autres États membres de l'UE sont du même avis. D'autre part, l'Autriche soutient fermement, avec les États de l'UE, les sanctions contre la Russie. Mais les sanctions devraient frapper la Russie plus durement que l'UE".

Et le ministre hongrois des Affaires étrangères Péter Szijjártó a déclaré :

"Pour nous, il y a une ligne rouge: la sécurité énergétique de la Hongrie. C'est pourquoi nous avons décidé que nous ne pouvions pas signer de sanctions contre le pétrole et le gaz".

Lutte pour le gaz du Qatar

Si l'approvisionnement en gaz russe est interrompu, l'économie allemande perdra environ 220 milliards d'euros au cours des deux prochaines années. Elle les perdrait même si elle trouvait une sorte de substitut pour les volumes supprimés, car il n'y aura jamais de prix aussi avantageux que ceux que Gazprom peut offrir. Le GNL australien ou colombien ne peut pas coûter la même chose que le gaz de pipeline russe. D'ailleurs, la Chine a plus que quintuplé ses achats de GNL par rapport à l'année dernière, ce qui signifie qu'il y aura également une bataille pour le gaz du Qatar. Dans l'ensemble, une autolimitation et une économie strictes seront la clé de sa survie dans les années à venir.

Robert Habeck, ministre de l'Économie et vice-chancelier de la République fédérale d'Allemagne, a déclaré :

"Je demande à chacun de faire sa part pour économiser l'énergie. A titre indicatif, j'essaierais d'économiser 10 pour cent, c'est faisable. Si vous chauffez votre appartement et fermez les rideaux le soir, vous pouvez économiser jusqu'à 5 pour cent d'énergie. Et si vous baissez la température de la pièce d'un degré, cela représente environ 6 pour cent. Bien sûr, ce n'est pas très confortable, mais personne n'aura froid. Une situation dans laquelle il y aurait des problèmes d'approvisionnement ou des entreprises qui devraient fermer serait un cauchemar politico-économique".

Il appelle ses concitoyens à économiser presque chaque semaine, c'est-à-dire avec la même fréquence que celle avec laquelle la Grande-Bretagne, par exemple, ment. Pour maintenir la folie des sanctions sur le continent, National Grid promet d'augmenter le transit du gaz produit en Norvège, mais on a pu voir comment la Grande-Bretagne se comporte réellement en cas de crise au plus fort de la pandémie, lorsqu'elle a réussi à faire passer tous les vaccins sous le nez de la Commission européenne. Et la Grande-Bretagne connaît déjà une crise du carburant. L'inflation explose, elle a atteint 7% en mars. Du jamais vu depuis 30 ans. Et cela vaut pour toute l'Europe.

Christine Lagarde, la présidente de la Banque centrale européenne, s'est exprimée à ce sujet :

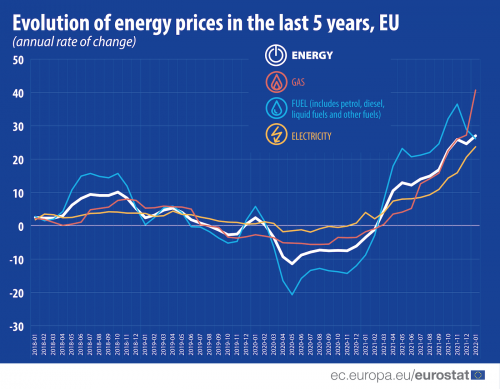

"L'inflation a atteint 7,5 pour cent en mars, contre 5,9 pour cent en février. Les prix de l'énergie ont augmenté depuis le début de la guerre et sont maintenant 45 pour cent plus élevés qu'il y a un an".

Vers une pauvreté assistée

Friedrich Merz en est convaincu:

"De toute façon, le sommet de notre prospérité est probablement derrière nous depuis longtemps. La situation devient de plus en plus difficile. Ce n'est pas seulement moi, en tant que chef de l'opposition, mais aussi le chancelier Olaf Scholz qui doit le dire à la population".

La fin de l'ère de la prospérité, il est amusant que ce diagnostic soit posé par le multimillionnaire et président du parti CDU, qui représente les intérêts des moyennes et grandes entreprises. Mais sur le fond, le pessimisme public est juste. L'inflation en Allemagne est déjà perçue par les consommateurs comme étant de 14%, soit le double de ce qu'elle est en réalité, ce qui signifie que le niveau de frustration augmente plus rapidement que le niveau de vie réel ne diminue. Et c'est là que diverses pensées malheureuses viennent à l'esprit.

Le Süddeutsche Zeitung écrit ainsi :

"Quel est le double standard aujourd'hui ? Il s'agit de condamner l'attaque russe, mais de refuser l'embargo sur le gaz. Il s'agit de condamner la guerre en Europe, mais de ne pas voir la guerre dans le reste du monde. C'est condamner la propagande russe, mais rester silencieux sur la guerre en Irak, qui a été déclenchée sur des mensonges. Il s'agit de diaboliser le gaz de Poutine, mais de ramper devant les Émirats. Et il faut en tout cas admettre comment on a été induit en erreur par Poutine, par les exigences démesurées de la Russie et par l'âme russe elle-même".

La citation du journal allemand sonne comme une invitation à réfléchir à ses propres erreurs.

Et bien sûr, on peut réfléchir, mais on ne peut rien changer. Le naufrage est un sentiment qui se répand lentement dans la société allemande. La situation avec Steinmeier, les accusations constantes de faiblesse contre le chancelier Scholz, la fissure au sein de la coalition, la pression de ceux qui considèrent les Allemands comme des alliés - on commence à comprendre son propre rôle dans le conflit entre l'Occident et la Russie. Pour le dire sans détour : même une guerre économique a besoin de chair à canon.

Fin de la traduction

12:16 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : allemagne, europe, affaires européennes, sanctions, sanctions antirusses, gaz |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Macron gagne, mais la fracture sociale interne de la France est irrémédiable

Macron gagne, mais la fracture sociale interne de la France est irrémédiable

Par Luigi Tedeschi

Source: https://www.centroitalicum.com/macron-vince-ma-la-frattura-sociale-interna-della-francia-e-insanabile/

L'abstentionnisme record est devenu une marée montante, qui affecte profondément la crédibilité et la représentativité de la classe politique dans le système libéral-démocratique occidental. Le clivage entre le peuple et les institutions est clair: le choc social entre le peuple et l'élite, entre le centre et la périphérie, reviendra très bientôt.

Macron a gagné et vaincu la menace souverainiste, illibérale et poutiniste de Le Pen. Macron est-il donc le héros de la croisade eurocratique contre le démon souverainiste dissolutiste? Non, l'UE veut juste se préserver et conserver son immobilisme cadavérique, révélant sa totale aversion au changement dans un contexte géopolitique mondial en mutation. L'élection présidentielle française, du moins en termes d'image médiatique, a été présentée comme un référendum dans lequel la survie même de l'Europe était en jeu. Soit l'UE (et l'OTAN), soit la dissolution de l'Europe elle-même (et de l'Occident). Soit avec l'OTAN, soit avec Poutine. Par répétition inlassable de ces contrastes, qui ont eu un effet médiatique dévastateur, une campagne de diabolisation authentique de l'idée de souveraineté lepéniste a eu lieu.

Macron a gagné, comme cela était largement prévisible. Mais, pour reprendre une vieille blague d'Altan, "le truc est là, vous pouvez le voir et tout le monde s'en fout". Il est tout à fait clair que le processus de décomposition progressive des institutions démocratiques en Europe est maintenant à un stade avancé. La dissolution des partis traditionnels (socialistes et gaullistes) est une réalité incontestable en France, comme en Italie. Sur les cendres de l'ancienne opposition entre la droite et la gauche, il est devenu nécessaire de créer un parti artificiel comme "En Marche" et un nouveau leader, Macron, ancien membre de la Banque Rothschild & Cie.

Donc un parti institutionnel, apte à créer une coalition républicaine en opposition à "l'ennemi absolu" souverainiste et poutiniste, dont le contenu politique peut se résumer au slogan "Tout sauf Le Pen". Par conséquent, Macron et son parti ont leur raison d'être en tant que garants de l'ordre eurocratique et de la loyauté de la France envers l'OTAN.

Ce sont en fait les valeurs qui donnent une légitimité démocratique aux gouvernements des pays de l'UE. En Italie, une fonction similaire est assurée par le PD, un parti minoritaire mais ancré dans les institutions politiques et économiques italiennes. En fait, le PD s'est vu déléguer la gouvernance de l'Italie par l'UE et l'OTAN.

Même en cas de victoire de Le Pen, le camp souverainiste n'aurait certainement pas été autorisé à gouverner le pays. En effet, Marine Le Pen se serait trouvée confrontée au bombardement quotidien des grands médias, qui auraient évoqué le danger d'une guerre civile fantôme, un système judiciaire hostile, une UE dominée par la rigueur financière allemande, et surtout elle aurait été rapidement déstabilisée par le jugement défavorable des marchés, seuls détenteurs d'un pouvoir économique pouvant conférer ou non une "légitimité démocratique" aux gouvernements, dans le contexte d'un système néolibéral qui a privé le consensus populaire de son pouvoir. L'expérience du gouvernement gialloverde en Italie est un témoignage tragique de la structure technocratique et financière dominante en Europe. Ce n'est pas une coïncidence si, dans la semaine précédant le second tour, Mme Le Pen a été inculpée de fraude financière présumée en rapport avec des fonds publics européens indûment dépensés pour 600.000 euros.

Macron a gagné grâce au soutien de l'establishment économique et financier, du courant dominant et de l'élite intellectuelle idéologiquement alignée sur les libéraux anglo-saxons. Macron a obtenu 18,7 millions de voix (58,55%) et Le Pen 13,3 millions de voix (41,45%). Mais le chiffre le plus remarquable est le pourcentage d'abstentionnistes (28%), le niveau le plus élevé depuis le scrutin de 1969. L'abstentionnisme record est devenu une marée montante, qui affecte profondément la crédibilité et la représentativité de la classe politique dans le système libéral-démocratique occidental. La fracture irrémédiable entre le peuple et les institutions est évidente : la somme du vote souverainiste et des abstentions dépasse largement 50% du corps électoral.

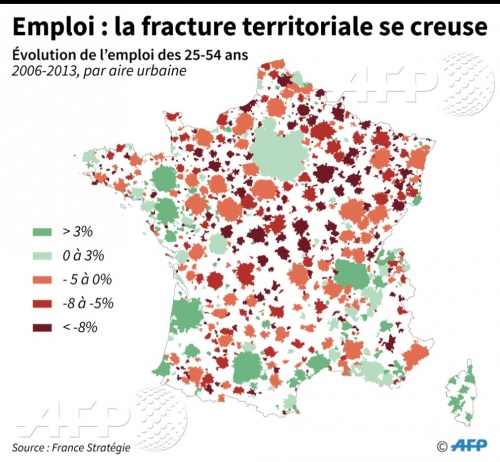

L'orientation nettement fondée sur la classe sociale du vote présidentiel français est également notable. Elle reflète la stratification sociale générée par le modèle néo-libéral, dans lequel prévalent des inégalités de plus en plus marquées et la prolétarisation rampante des classes moyennes, c'est-à-dire les perdants de la mondialisation. Le vote pour Macron s'est en effet concentré dans la bourgeoisie et les classes éduquées des grandes villes, tandis que celui de Le Pen s'est concentré dans les régions du Nord décimées par la désindustrialisation et dans l'immense province agricole française, de plus en plus appauvrie et dépeuplée.

La première présidence de Macron a débuté sous les auspices d'une réforme libérale des institutions et de l'économie, qui s'est fatalement heurtée au malaise social croissant apparu d'abord avec la révolte des gilets jaunes, puis avec la crise de la pandémie et enfin avec la crise russo-ukrainienne. Nous ne savons pas comment Macron pourra imposer de nouvelles réformes libérales face à un choc social entre le peuple et l'élite, entre le centre et la périphérie, qui ressurgira. La fracture interne de la France est désormais irrémédiable. Un scénario similaire se déroulera bientôt en Italie. Il est difficile de voir comment la vision politique libéraliste de Macron peut guérir la pays. Le gouvernement Macron, ainsi que le gouvernement de Draghi en Italie, sont l'expression d'un système qui veut préserver les équilibres sociaux élitistes en Europe, en conflit ouvert avec les classes populaires: l'UE est un organe réactionnaire et répressif qui ne défend que sa propre subsistance.

En ce qui concerne l'Europe, les propositions de Le Pen, orientées vers une réforme des politiques publiques européennes, qui prévoirait le rapatriement des pouvoirs déjà dévolus des Etats vers l'UE, une politique anti-immigration plus efficace et la prévalence du droit national sur le droit européen, il faut noter que Macron lui-même a été confronté à de multiples conflits entre les intérêts nationaux et européens. Le projet d'"intégration différenciée" des États membres de l'UE n'a pas été couronné de succès. Macron a réussi à imposer à l'Allemagne le lancement de l'UE nouvelle génération, mais s'est heurté au veto des pays frugaux du Nord concernant la réforme du pacte de stabilité (un projet partagé avec Draghi) et la proposition de partager la dette contractée par les États pendant la crise de la pandémie.

En ce qui concerne l'Europe, les propositions de Le Pen, orientées vers une réforme des politiques publiques européennes, qui prévoirait le rapatriement des pouvoirs déjà dévolus des Etats vers l'UE, une politique anti-immigration plus efficace et la prévalence du droit national sur le droit européen, il faut noter que Macron lui-même a été confronté à de multiples conflits entre les intérêts nationaux et européens. Le projet d'"intégration différenciée" des États membres de l'UE n'a pas été couronné de succès. Macron a réussi à imposer à l'Allemagne le lancement de l'UE nouvelle génération, mais s'est heurté au veto des pays frugaux du Nord concernant la réforme du pacte de stabilité (un projet partagé avec Draghi) et la proposition de partager la dette contractée par les États pendant la crise de la pandémie.

Les propres propositions de Macron pour la création d'une force de défense européenne autonome n'ont pas abouti, étant donné la réticence évidente des pays d'Europe de l'Est et du Nord, qui exigent plutôt un renforcement de l'OTAN. Le propre rôle prééminent de la France en Europe dans le domaine de la défense, en tant que seul pays de l'UE (après le Brexit) doté de l'arme nucléaire et membre permanent du Conseil de sécurité de l'ONU, pourrait être remis en question par les perspectives de réarmement de l'Allemagne. La présidence de l'UE et les initiatives diplomatiques de Macron dans la crise russo-ukrainienne ne sont pas formidables. Le bilan global de la première présidence de Macron est donc négatif, comme le soulignait Giulio Sapelli quelques jours avant le scrutin: "Si Macron gagne les élections, comme cela est hautement probable, la réduction de la puissance internationale de la France continuera à être douloureuse et profonde et entraînera de plus en plus toute l'Europe, avant l'UE, avec elle. La présidence française de l'UE a déjà été un échec que seules la guerre d'agression russe et la crise énergétique peuvent dissimuler. Le macronisme est la destruction de la force civique de la France par la destruction de ses bastions politiques et institutionnels historiques: l'État napoléonien et l'Armée.

Les déchirures entre les nations européennes sont profondes et seront exacerbées par l'incapacité de Macron à développer une politique de puissance française qui rappelle de loin la fierté gaulliste et le radicalisme républicain de Jean-Pierre Chevènement: les deux seuls grands leaders, De Gaulle et Chevènement, que la France a produit après la Seconde Guerre mondiale, éclipsés par le fascinant écran de fumée littéraire de Mitterrand. Macron a fait en France ce que la libéralisation par le haut souhaitée par les États-Unis et le Royaume-Uni a fait en Italie, en utilisant le système judiciaire et la crise morale d'une nation déjà épuisée par la confusion institutionnelle et l'incapacité expansionniste internationale de sa classe moyenne supérieure industrielle et étatique-financière".

L'Europe traverse une crise politique et institutionnelle sans solution, car le système démocratique libéral s'est révélé irréformable. Parce qu'avec l'UE, la démocratie a dégénéré en démocratie libérale. Le libéralisme et la démocratie ne se sont pas avérés compatibles. La démocratie libérale est fondée sur l'individu, ne tient pas compte de la communauté, protège les droits de l'homme et les libertés individuelles, mais la valeur du bien commun, qui est une caractéristique de la démocratie ancienne, lui est étrangère. Par conséquent, dans une démocratie libérale, la représentation politique est le reflet des relations entre les groupes d'intérêt qui dominent la société civile. L'idéologie du progrès est inhérente à la démocratie libérale. Le pouvoir politique est donc de plus en plus dévolu à des oligarchies technocratiques. La démocratie libérale est donc un système destiné à se transformer en oligarchie. L'inévitable dérive élitiste de la démocratie libérale est analysée comme suit par Alain de Benoist dans son essai "La crise actuelle de la démocratie": "L'expression "démocratie libérale" associe deux termes censés être complémentaires, alors qu'ils sont contradictoires. Cette contradiction, qui se manifeste pleinement aujourd'hui, menace les fondements mêmes de la démocratie. "Le libéralisme met la démocratie en crise", dit Gauchet. Chantal Mouffe a observé à juste titre que "d'un côté, nous avons la tradition libérale constituée par l'État de droit, la défense des droits de l'homme et le respect de la liberté individuelle; de l'autre, la tradition démocratique dont les idées maîtresses sont celles de l'égalité, de l'identité entre gouvernants et gouvernés, et de la souveraineté populaire. Il n'y a pas de relation nécessaire entre ces deux traditions différentes, seulement une articulation historique contingente".

Quiconque ne voit pas cette distinction ne peut rien comprendre à la crise actuelle de la démocratie, qui est précisément une crise systémique de cette "articulation historique contingente". La démocratie et le libéralisme ne sont en aucun cas synonymes ; en effet, sur des points importants, ce sont même des notions opposées. Il peut y avoir des démocraties non libérales (démocraties tout court) et des formes de gouvernement libérales qui n'ont absolument rien de démocratique. Carl Schmitt est allé jusqu'à dire que "plus une démocratie est libérale, moins elle est démocratique".

11:13 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : france, actualité, europe, affaires européennes, emmanuel macron, présidentielles françaises 2022 |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Le général de brigade à la retraite Erich Vad: il règle maintenant ses comptes avec les écolos fauteurs de guerre

Le général de brigade à la retraite Erich Vad: il règle maintenant ses comptes avec les écolos fauteurs de guerre

Par Sven Reuth

Source: https://www.compact-online.de/brigadegeneral-a-d-erich-vad-jetzt-rechnet-er-mit-gruenen-kriegstreibern-ab/?mc_cid=3b95b79c94&mc_eid=128c71e308

Une escalade de la guerre en Ukraine comporte d'énormes risques pour l'Allemagne. C'est ce que le général de brigade à la retraite Erich Vad n'a cessé de rappeler ces dernières semaines. Il s'est exprimé clairement sur le bellicisme des Verts.

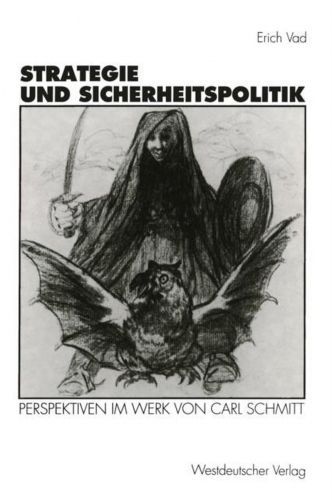

Erich Vad est un homme qui possède la plus grande expérience et a occupé les plus hauts postes de direction. De 2006 à 2013, il a été chef de groupe à la Chancellerie fédérale, secrétaire du Conseil fédéral de sécurité et conseiller en politique militaire de la chancelière Angela Merkel. Cette ascension a été possible malgré le fait que Vad ait donné en 2003 une conférence à l'Institut für Staatspolitik sur le thème "Le maintien de la paix et la géopolitique dans la pensée de Carl Schmitt". En 1996, Vad avait déjà publié le livre Stratégie et politique de sécurité. Perspectives dans l'œuvre de Carl Schmitt.

"Nous n'avons pas besoin d'une guerre par procuration"

Il y a deux semaines à peine, Vad avait déjà provoqué un scandale selon l'ambassadeur ukrainien Melnyk parce que, dans une interview accordée à Die Welt, il ne voulait pas attribuer à Poutine une intention de bombarder une clinique et faisait en outre référence au nombre élevé de victimes que les guerres menées par l'Occident avaient fait au cours des dernières décennies. Son message principal à l'époque était le suivant:

"Si nous ne voulons pas de la troisième guerre mondiale, nous devrons tôt ou tard sortir de cette logique d'escalade militaire et entamer des négociations".

Hier, dans le talk-show Maybritt Illner, Erich Vad a de nouveau suscité l'irritation en critiquant à la fois la ligne belliciste des Verts et l'attitude complètement naïve de la majorité de la société allemande face à une éventuelle escalade de la guerre en Ukraine. Son message de base était que l'établissement d'un cessez-le-feu rapide devrait être prioritaire par rapport à la question de savoir quel camp remporterait la victoire à la fin.

Vad a déclaré à ce sujet:

"Nous n'avons pas besoin en Europe centrale d'une guerre par procuration pendant des années, qui a le potentiel de dégénérer en guerre nucléaire".

"Nous ne voulons pas d'une victoire de l'Ukraine"

Toute "rhétorique guerrière" devrait être évitée. Afin de montrer clairement que la négociation rapide d'un cessez-le-feu et la recherche d'une solution politique à long terme au conflit sont prioritaires, aussi le gouvernement allemand devrait enfin déclarer :

"Nous ne voulons pas la victoire de l'Ukraine".

Il s'est montré particulièrement critique à l'égard du rôle actuel des Verts dans la politique fédérale. Il a déclaré à ce sujet :

"Ce qui me dérange, c'est quand les politiciens des Verts présentent les solutions militaires comme l'objectif ultime. C'est complètement fou ! Ce sont des politiciens Verts qui ont refusé et condamné le service militaire à l'époque !"

Vad avait déjà déclaré dans son interview à Die Welt qu'il estimait totalement erroné de dénier au président russe son humanité et de le qualifier de despote pathologique avec lequel personne ne peut plus parler. Après tout, il y a eu dans un passé récent d'autres guerres terribles et contraires au droit international, en Irak, en Syrie, en Libye et en Afghanistan, menées par des puissances occidentales.

Voici revenu le temps du nazisme

La bulle de gauche libérale et woke de Twitter est déjà en ébullition suite aux déclarations de Vad. On y fait notamment référence à un texte de Vad paru il y a 19 ans dans le magazine intellectuel de droite Sezession pour justifier l'interdiction imposée à cet expert patenté de participer à un talk-show. Si la campagne devait aboutir, l'un des rares critiques de la guerre encore en vie disparaîtrait de la scène publique.

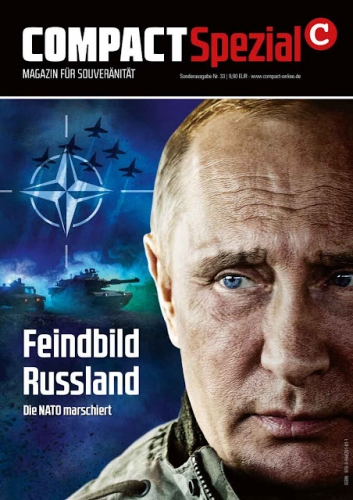

COMPACT-Spécial "L'image de l'ennemi russe - L'OTAN en marche" fournit les arguments pour un nouveau mouvement pour la paix. L'Allemagne doit rester neutre dans le conflit ukrainien - c'est la seule façon de protéger notre pays ! Commandez ici: https://www.compact-shop.de/shop/compact-spezial/compact-... !

10:25 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : actualité, ukraine, allemagne, verts, écologistes, erich vad, europe, affaires européennes |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

mardi, 26 avril 2022

Les risques pour la Finlande (et au-delà) d'abjurer la neutralité

Les risques pour la Finlande (et au-delà) d'abjurer la neutralité

Les Finlandais, avec leurs grosses vieilles chaussures de paysans bien ancrées dans le sol, étaient autrefois politiquement concrets. Mais maintenant, ils continuent de répéter le mantra "la situation sécuritaire a changé". Ce qui n'est pas vrai du tout, car dans le quadrant nord de la Baltique, les Russes n'ont fait aucun mouvement dans cette délicate partie d'échecs avec l'OTAN ; au contraire, ils ont éloigné des troupes de la frontière finlandaise, probablement pour les envoyer en Ukraine.

par Luigi De Anna

Source: https://www.barbadillo.it/104133-i-rischi-per-la-finlandia-e-non-solo-che-abiura-la-neutralita/

HANNIBAL AD PORTAS... OU... DELENDA CARTHAGO ?

Observer une guerre de loin est déjà dramatique, mais l'avoir vraisemblablement à sa porte conduit au découragement. Découragement, pour l'essentiel, de la capacité des politiciens à concevoir une stratégie qui préserve les intérêts de l'Europe, et non ceux de son puissant allié, les États-Unis.

J'ai vécu en Finlande pendant plus de 50 ans. Lorsque je suis arrivé là-bas, la règle stricte de la "finlandisation" était en vigueur, c'est-à-dire que la Finlande restait un pays libre avec un système parlementaire de style occidental, mais n'interférait pas avec les intérêts de l'Union soviétique et, en tant que nation neutre, faisait office d'État tampon entre l'Est et l'Ouest. Il s'agissait de la ligne dite Paasikivi-Kekkonen, poursuivie ensuite de manière substantielle par Mauno Koivisto. Avec la chute de l'Union soviétique, la Finlande a commencé à regarder vers l'ouest, oubliant ce que le président Koivisto avait dit sur le danger de ce renversement de la politique étrangère, car "celui qui s'incline d'un côté montre son derriere à l'autre".

Urho Kekkonen et Mauno Koivisto.

Le parti conservateur Kokoomus est au gouvernement depuis des années, et devrait revenir lors des prochaines élections. Le centre et la droite finlandais ont été anti-russes en raison de leur vocation naturelle à s'occidentaliser, mais aussi en raison de l'attrait génétique fort, presque inéluctable, qui pousse les peuples riverains de la Baltique à l'anti-russisme. Alors que l'Estonie, la Lettonie et la Lituanie faisaient partie de l'Union soviétique, la Finlande, comme mentionné, avait conservé son indépendance.

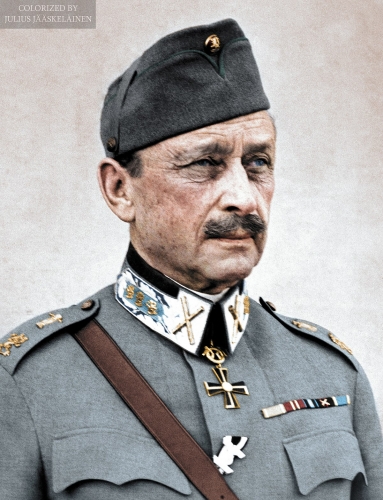

Nous pourrions nous demander pourquoi. En 1944, Staline aurait pu pousser ses armées jusqu'à Helsinki et ne l'a pas fait. La version finlandaise pour expliquer cette décision est liée au mythe de l'héroïsme de ses soldats, né avec la soi-disant "guerre d'hiver", de novembre 1939 à mars 1940. Sans doute héroïque, mais pas suffisamment pour arrêter l'Armée rouge qui, après être arrivée à Berlin, aurait bien pu arriver à Helsinki. Staline n'a pas non plus réalisé en Finlande l'assimilation des pays que Yalta lui avait accordée, alors qu'il existait en Finlande un parti communiste fort qui aurait été bien adapté à cette tâche. Staline juge plus utile d'avoir une Finlande neutre, et surtout il ne veut pas risquer de pousser la Suède dans le camp occidental, ce qui aurait fermé la Baltique à sa flotte. La Finlande a payé les réparations de guerre, a jugé dans son propre petit Nuremberg (mais sans bourreaux américains ou soviétiques) les responsables de l'alliance avec l'Allemagne (mais pas le maréchal Mannerheim, probablement le principal architecte de l'accord avec Staline) et, année après année, a prospéré grâce au commerce avec sa voisine orientale.

Carl-Gustav Emil Mannerheim.

Nous en arrivons à la crise ukrainienne: la Finlande s'aligne immédiatement sur le récit atlantiste. Les nouvelles sont pleines d'images larmoyantes, les (rares) talk-shows (les Finlandais sont notoirement peu loquaces) n'invitent que ceux qui accusent la Russie d'agression, de massacres, etc. etc., mais jamais quelqu'un qui, je ne dirai pas défend la Russie, mais qui explique ses raisons. Les plus modérés dans cette course à l'anti-russisme semblent être les militaires, invités en tant qu'experts, bien conscients de là où cela pourrait mener.

Sic fuit in votis. Hier, 13 avril, le gouvernement finlandais a présenté son Livre blanc sur la sécurité, ou plutôt sur les perspectives de cette crise internationale, qui recommande l'adhésion de la Finlande à l'OTAN.

Mais qui menace la Finlande ?

Personne. Et, chose intéressante, personne n'a posé cette question très simple. On ne fait que plaider... "si la Russie... si la situation... si un jour...". En finnois, il existe un verbe, "jossitella", qui indique précisément la futilité des hypothèses. Les Finlandais, avec leurs grosses vieilles chaussures de paysans bien ancrées dans le sol, étaient généralement politiquement concrets. Mais maintenant, ils continuent de répéter le mantra "la situation sécuritaire a changé". Ce qui n'est pas vrai du tout, car dans le quadrant nord de la Baltique, les Russes n'ont pas fait un geste dans cette délicate partie d'échecs avec l'OTAN; au contraire, ils ont déplacé des troupes de la frontière finlandaise, probablement pour les envoyer en Ukraine.

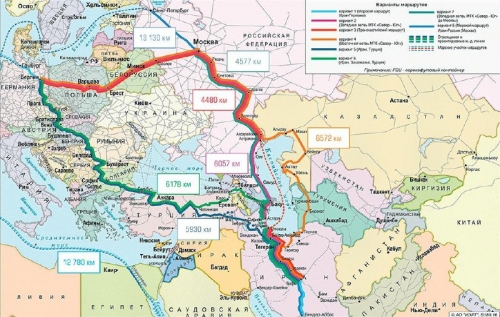

Oui... la frontière. Une frontière de près de 1300 km, qui passe non loin de Saint-Pétersbourg, la patrie de Vladimir Poutine, qui pourrait un jour voir de sa fenêtre, au-delà des dômes en bulbe de ses belles églises, les missiles nucléaires de l'OTAN. L'alliance atlantique s'étendrait pratiquement jusqu'à Mourmansk, la base navale la plus importante de la Russie, qui abrite sa flotte de sous-marins nucléaires. Et Mourmansk est la clé stratégique de la nouvelle route arctique qui s'ouvre, qui unira le commerce asiatique à l'Occident.

Comment Poutine pourrait-il laisser ces deux zones sensibles, le golfe de Finlande et la péninsule de Kola, être assiégées par l'OTAN ?

L'absurdité est que la Finlande demande à rejoindre l'OTAN (sans doute le Parlement le proposera-t-il) pour éviter une éventuelle intervention russe et, ce faisant... ils la provoquent ! Vraiment brillant !

Les Finlandais, comme de bons vieux paysans, se croient malins: ils veulent rejoindre l'OTAN maintenant parce que la Russie n'a pas assez de soldats pour l'envahir... oui, c'est vrai, les soldats sont ailleurs, mais la Russie, ne pouvant utiliser de chars utiliserait... les sages dirigeants finlandais n'y pensent-ils pas? Les armes nucléaires tactiques de la Russie devraient les faire méditer. Les temps désespérés appellent des mesures désespérées, c'est peut-être aussi un dicton slave.

À la folie incontestable des dirigeants actuels de la Finlande, il faut cependant ajouter une autre motivation: faire plaisir aux États-Unis. La Finlande coopère militairement avec l'OTAN depuis longtemps, organisant des exercices militaires conjoints avec elle, tout récemment il y a quelques semaines en Norvège, manifestement en préparation de l'activation de l'offensive arctique. L'année dernière, la Finlande a acheté les F-35 dont elle avait besoin pour remplacer les vieux Hornets, mais ce sont des avions offensifs, alors pourquoi? Au lieu de se doter de systèmes de missiles défensifs, à la suggestion des Américains, ils ont opté pour des jets qui transportent une telle charge de missiles et de bombes ainsi que des équipements électroniques que... de temps en temps, ils tombent, comme nos Starfighters, appelés tombes volantes.

Le Premier ministre finlandais, Sanna Marin (photo), a clairement indiqué avant-hier que des consultations avec les États-Unis sur cette possibilité de rejoindre l'OTAN sont en cours. Et voici la véritable raison pour laquelle le gouvernement de centre-gauche de Marin fait pression en faveur de l'OTAN: les États-Unis ont besoin d'un nouveau front sur lequel engager la Russie, en la détournant et en l'affaiblissant ainsi sur le front ukrainien. Sans aucun doute une stratégie intelligente et utile. Pour eux. Mais pas pour la Finlande, qui entre désormais allègrement dans la tanière de l'ours pour le réveiller. Une chose que les anciens chasseurs finlandais savaient être très risquée.

Mais il n'y a plus de vieux chasseurs en Finlande. Le pays est gouverné par une troïka de cinq secrétaires de parti, tous âgés d'une trentaine d'années. La nouvelle histoire nous a appris qu'il existe des composantes apparemment irrationnelles mais quantifiables dans l'histoire. Et sans doute le récit médiatique des enfants ukrainiens comme victimes de la guerre agit-il sur l'inconscient de ces jeunes mères. Mais les mères devraient aussi penser à leurs enfants plus âgés: ceux que la Finlande enverra inévitablement à la mort dans une guerre absurde et futile à venir.

Delenda Carthago... oui, mais quel Carthago ?

Luigi De Anna

17:54 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : politique internationale, actualité, finlande, neutralité, espace baltique, mer baltique, europe, affaires européennes |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Bombes de vérité : comment les Etats-Unis ont mis la main sur l'Ukraine

Bombes de vérité : comment les Etats-Unis ont mis la main sur l'Ukraine

par Fabio Mini

Source : Il Fatto quotidiano & https://www.ariannaeditrice.it/articoli/bombe-di-verita-cosi-gli-usa-hanno-messo-le-mani-sull-ucraina

Il y a quelques semaines, lors d'une apparition à la télévision américaine, la célèbre journaliste Lara Logan a lâché tant de "bombes de vérité" sur un public médusé que les présentateurs du programme ont dû supplier (sur des téléphones internes) pour une pause commerciale. Les "bombes" étaient en fait des choses que les soi-disant complotistes disaient au monde entier depuis longtemps, sauf aux Américains bien sûr.

Outre la rhétorique poutiniste, qui reflète la rhétorique anti-poutiniste, ce qui est étonnant, c'est la réaction du public: une avalanche de compliments pour les vérités non dites, quelques objections, de nombreuses expressions d'admiration pour le courage et tout autant de prières de la part de ceux qui craignent pour la vie de Lara.

Lara Logan.

Même au pays de la liberté d'expression, si vous dites quelque chose qui dérange les pouvoirs en place, vous êtes mort. La tirade de Lara Logan est plus que cela: c'est un appel clair à la responsabilité du leadership américain dans ce qui se passe en Ukraine. Là-bas, la rhétorique des bons gars et des méchants voyous a explosé, tout comme au Vietnam, en Irak et en Afghanistan, mais pour les Américains qui se sont habitués à l'idée d'être les bons gars, c'est toujours une "découverte" saine mais traumatisante.

Rechercher des traces d'une implication directe des États-Unis dans cette guerre, présentée comme une question subalterne qui ne concerne que la Russie et l'Ukraine et tout au plus l'UE ou l'OTAN et la Russie, est moins difficile qu'il n'y paraît.

Les États-Unis sont présents en Ukraine depuis 1991 et n'en sont jamais repartis. Lorsque l'URSS s'est désintégrée, l'Ukraine s'est retrouvée avec le troisième arsenal nucléaire le plus puissant du monde, après les États-Unis et la Russie. Pas moins de 176 missiles intercontinentaux avec 1240 têtes nucléaires.

Plusieurs dizaines de bombardiers nucléaires stratégiques avec 600 missiles et bombes à gravité et 3000 dispositifs nucléaires tactiques. Les États-Unis et la Russie se sont mis d'accord sur une réduction de l'armement nucléaire et, avec l'idée que l'Ukraine serait toujours dans la sphère d'influence de la Russie, ont décidé d'éliminer tout l'armement nucléaire existant en Ukraine.

À partir de 1992, l'Ukraine a exploité la sensibilité de l'Occident à la question nucléaire et, jusqu'en 1994, elle a continué à gagner du temps et à marchander son adhésion au traité de non-prolifération et la ratification de START. Le démantèlement de chaque silo à missiles coûtait 1 million de dollars (à l'époque) et les États-Unis ont fourni 399,2 millions de dollars pour payer Bechtel Corp. afin de sous-traiter les travaux.

La dénucléarisation a été achevée, du moins sur le papier, en 1996, mais ce n'est qu'en 2000 que les bombardiers stratégiques ont été remis à la Russie en échange d'un allègement des dettes de gaz qui s'étaient accumulées. L'Ukraine a hérité d'environ 30 % de l'industrie militaire soviétique, qui représentait 50 à 60 % de toutes les entreprises ukrainiennes et employait 40 % de sa population active. L'armée ukrainienne a échangé des armes conventionnelles et signé des contrats avec des entreprises commerciales. Les premiers contrats de livraison d'armes à l'Iran, signés à la mi-1992, ont provoqué une réaction négative en Occident (surtout aux États-Unis). Depuis lors, l'Ukraine n'a cessé de produire des armes et de les vendre sur le marché noir à divers pays, toujours sous l'œil attentif des États-Unis, de la Russie et de leurs trafiquants et oligarques.

Depuis la révolution orange de 2004, les États-Unis sont intervenus en Ukraine pour déstabiliser les relations avec la Russie. Les différentes tentatives se sont concrétisées dix ans plus tard avec les incidents de Maidan. L'ingérence est flagrante et il s'agit, en l'occurrence, de l'appel téléphonique de Victoria Nuland - "Fuck the EU !" - pour révéler qu'elle ne se contente pas de surveiller les événements, mais qu'elle assure une direction politique et opérationnelle. De 2014 à 2022, grâce aux sanctions et à l'aide militaire des États-Unis et de l'OTAN, l'armée a été restructurée, des milices paramilitaires ont été équipées et entraînées, et des laboratoires de recherche biologique ont été installés par des entreprises américaines. Dans une tentative grotesque de faire passer la question des laboratoires pour des fake news, l'équipe Vox Check écrit: "Des laboratoires biologiques américains secrets en Ukraine? Un mythe de la propagande russe. Rien ne prouve qu'il y en ait... Cependant, il existe une coopération entre les institutions ukrainiennes et américaines. Depuis 2005, les États-Unis ont aidé à moderniser les laboratoires ukrainiens, à mener des recherches et à améliorer la sécurité pour prévenir les épidémies de maladies infectieuses dangereuses par le biais du programme de réduction des menaces biologiques. Pendant toute la période de coopération, les États-Unis ont investi environ 200 millions de dollars dans le développement de 46 laboratoires et institutions médicales en Ukraine. Ces institutions ne sont pas impliquées dans le développement d'armes chimiques ou biologiques".

Et en effet, comme la mutuelle ukrainienne ne s'occupe pas de vaccins mais d'agents pathogènes à haut risque, l'Organisation mondiale de la santé a conseillé à l'Ukraine, le 11 mars dernier (source : Reuters), de détruire ces agents hébergés dans les laboratoires de santé publique du pays afin d'éviter "toute fuite potentielle" qui propagerait des maladies au sein de la population.

Mais la question est que "au contraire, les États-Unis ont lancé un programme visant à empêcher le développement de telles armes. L'Union soviétique avait son propre programme d'armes biologiques. Après l'effondrement, des matières biologiques dangereuses sont restées sur le territoire de l'Ukraine. Le programme américain vise à garantir que ces matériaux ne soient pas volés ou utilisés à des fins autres que la recherche. Jusqu'en 2014, le programme s'étendait également aux laboratoires russes".

Cependant, ces matériaux laissés par l'URSS soulèvent la question d'autres matériaux soviétiques en Ukraine. L'URSS disposait d'un stock de près de 40.000 tonnes d'agents chimiques neurotoxiques, vésicants et suffocants. Selon certains rapports, le stock total a dépassé 50.000 tonnes, avec un stock supplémentaire de 32.300 tonnes d'agents phosphorés. Quelle proportion de ce stock est restée en Ukraine?

Officiellement aucune, mais si les armes biologiques sont laissées, pourquoi ne pas laisser aussi les armes chimiques que la Russie et les États-Unis possèdent encore?

Les traces des États-Unis en Ukraine sont également présentes ici, ne serait-ce que parce qu'elles savent exactement où elles ont abouti. Si l'on devait mesurer l'implication américaine par le nombre de soldats américains sur le terrain, on peut se limiter à compter les soi-disant volontaires parmi les combattants et les contractants étrangers. Le président Zelensky a parlé d'environ 20.000 volontaires du monde entier (y compris des États-Unis).

La "légion internationale" a été intégrée aux forces de défense de l'Ukraine, afin de ne pas tomber dans un vide juridique sur le statut des mercenaires. En fait, nombre d'entre eux sont payés avec des fonds donnés par les États-Unis et l'Europe, ainsi que par des "particuliers". Le commandant de la Légion géorgienne, M. Mamulashvili, procède depuis avril 2014 au recrutement et à la formation de bataillons composés de professionnels, principalement américains et britanniques. Eante a personnellement dirigé ses bataillons contre les Russes à l'aéroport d'Hostomel, dans la région de Kiev. Si l'on veut ensuite examiner le rôle des États-Unis dans la question ukrainienne à quelques pas de la frontière, on peut en déduire que la "défense" de l'OTAN est peu défensive et très provocatrice. Le Pentagone a repositionné ses troupes avant l'invasion russe. Les 160 hommes de la Garde nationale de Floride (instructeurs) ont été retirés d'Ukraine. Sur les quelque 40.000 soldats américains présents en Allemagne, plusieurs milliers ont été déployés dans les pays voisins de l'OTAN. L'OTAN a déployé 5000 soldats depuis 2014 dans les États baltes et les États-Unis ont envoyé 5000 autres soldats en Allemagne.

La présence américaine dans la cyberguerre est également ancienne. La dernière attaque russe contre le réseau ukrainien de contrôle de l'électricité (8 avril) a été miraculeusement évitée grâce à Microsoft et à la société slovaque Eset. Le collectif Anonymous a attaqué à plusieurs reprises la Russie et s'est entièrement rangé du côté de l'Ukraine. L'origine des membres éphémères du collectif est des plus variées et offre diverses possibilités aux agents de la cyberguerre de se déguiser derrière cette marque. La même opportunité est offerte aux sites anti-russes comme RURansom Wiper et à des dizaines d'autres plateformes formelles et informelles. Les grandes entreprises américaines sont toutes présentes en Ukraine et boycottent et censurent toute communication "indésirable". Il s'agit d'activités collatérales mais importantes.

Cependant, l'implication la plus importante se situe avec et derrière l'envoi de fonds et d'armes. Le président Biden a porté la contribution américaine à 1 milliard de dollars en une semaine et à 2 milliards de dollars depuis son entrée en fonction. Les nouvelles armes envoyées comprennent des missiles Stinger (800), des missiles Javelin (2000) et des systèmes antichars (6000). Le transfert de véhicules blindés, de technologies et de drones d'autres pays vers l'Ukraine a été autorisé. Beaucoup de ces systèmes ont également besoin de leurs opérateurs et ceux-ci sont normalement fournis par des sociétés militaires privées, qui continuent à recruter du personnel spécialisé.

Avec tout cela, seul un pays délibérément laissé dans l'ignorance peut encore penser qu'il n'est pas impliqué et peut avoir une Pâques paisible.

16:56 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : ukraine, états-unis, europe, affaires européennes, politique internationale, lara logan |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

Après la conquête de la mer d'Azov

Après la conquête de la mer d'Azov

par Federico Dezzani

Source: https://www.ariannaeditrice.it/articoli/dopo-la-conquista-del-mare-di-azov & Federico Dezzani

Au 57e jour de la guerre russo-ukrainienne, le ministère russe de la Défense a annoncé la conquête de la ville de Marioupol. Il est temps d'analyser comment la campagne militaire a évolué au cours des deux derniers mois, comment elle pourrait évoluer dans un avenir proche et, surtout, quelles seront ses répercussions internationales: il est de plus en plus évident que les puissances anglo-saxonnes veulent utiliser le conflit pour affaiblir la Russie et, en même temps, déstabiliser l'Allemagne et l'Italie.

Une guerre par procuration tous azimuts

Un peu moins de deux mois après le début des hostilités russo-ukrainiennes, le ministère russe de la Défense a annoncé la conquête de la ville de Marioupol, qui compte environ 400.000 âmeset est située sur le littoral de la mer d'Azov: seul le grand complexe sidérurgique, qui fait partie du kombinat de l'acier construit dans le Donbass dans les années 1930, reste encore aux mains des troupes ukrainiennes désormais clairsemées, mais sa chute est une question de temps. La Russie a donc obtenu un premier résultat stratégique tangible: elle a recréé un pont terrestre avec la péninsule de Crimée (annexée en 2014) et transformé la mer d'Azov en un lac intérieur. Les frontières russes sont donc revenues, sur le front sud, à la conformation de la première moitié du XVIIIe siècle, lorsque l'empire tsariste a réussi à arracher la mer d'Azov aux Turcs et à entrer dans les mers chaudes.