Presseschau

Dezember 2016

Wieder einige Links. Bei Interesse anklicken...

###

AUßENPOLITISCHES

RT Exklusiv: Assange über die geheime Welt der US-Regierung

Beginn eines amerikanischen Albtraums?

Trump gewinnt Präsidentschaftswahl

Gabriel: Trump schlimmer als Islam

(Deutsche Reaktionen…)

US-Wahl

Das große Wehklagen

(Ebenfalls zu den Reaktionen der deutschen Journalisten zu Trump…)

Sichere Verlierer: Medien und Demoskopen

Good Night Medien

Unser Zwangsfernsehen war laut Forsa und Co. dicht am Wahlergebnis dran

New Balance lobt Trump – Kunden verbrennen ihre Sneaker

NGO mit Verbindungen zu Clinton und Soros wiegelt zu Anti-Trump-Protesten auf

Black Trump Supporter Smacks Down CNN Reporter for Race Baiting

The Huffington Post ending editor's note that called Donald Trump 'racist'

(Nur hohle Worte…)

Nachgehakt: 23 Stars hatten angekündigt auszuwandern, sollte Trump Präsident werden

Ex-Kommunarde über Donald Trump

"Trump ist der erste Internetmensch" - so erklärt Langhans die US-Wahl

Richtungswechsel in den USA

Das ist Trumps Wirtschaftsprogramm

Die Political Correctness ist am Ende

von Frauke Petry

Meinung

Eine Epoche geht zu Ende

von Thomas Fasbender

Donald Trump – Alternative für Amerika?

Szene-Kaleidoskop III: Bachmann, Trump, Kernschmelze in USA

US-Wahl

„Aber Hillary hat doch mehr Stimmen gewonnen!“

von Lukas Mihr

Streiflicht

Der Super-GAU für Linke

von Dieter Stein

Putin? Merkel? Trump trifft lieber Brexit-Kämpfer Farage

Vor dem Hass kommen Verachtung und Ignoranz

Richtigstellung einer verzerrten Kampagne

Trump und der Kreml

Der Friede profitiert

von Thomas Fasbender

Obama lobt Merkel für ihre „Stärke und Entschlossenheit“

Trotz neuer lukrativer Jobs

Ehemalige EU-Kommissare erhalten 100.000 Euro Übergangsgeld

EU: Belohnung für Versagen?

Kommissionschef Jean-Claude Juncker erhält eine Gehaltserhöhung in Höhe von 10.362 Euro

Schweden baut sich neuen staatlichen Medienkonzern

Schluss mit Münzen und Scheinen

Schweden plant digitale Währung

Die schwedische Zentralbank will ihrem Ruf als Vorreiter in der Finanzwelt gerecht werden und plant die Einführung einer Digitalwährung. Der Weg für die E-Krone scheint geebnet.

Nach Wetterchaos: Stockholm verteidigt gendergerechtes Schneeräumen

Französischer Trump

François Fillon – Stichflamme aus der Tiefe Frankreichs

Die EU-Abgeordnete tobt

Großbritannien will Steuern auf Rekordtief senken

US-Armee soll Gefangene in Afghanistan gefoltert haben

Als syrischer Christ in Deutschland – ein Gespräch mit Kevork Almassian

Erdogan droht mit Grenzöffnung

Recep Tayyip Erdogan droht mit Öffnung der Grenzen

(Dazu ein Kommentar…)

Meinung

Die Supereuropäer pfeifen im Walde

von Thomas Fasbender

Notstandsdekret eingesetzt

Erdoğan schließt erneut Zeitungen und Vereine

(Überall nur noch sich untereinander streitende "Nazis" und "Rassisten"…)

Nach „Nazi-Herrschaft“-Vorwurf wirft Türkei EU „Rassismus“ vor

Südafrika: Oppositionspolitiker fordert Enteignung von Weißen

Reaktionen auf Fidel Castros Tod

"Brutaler Diktator, Horror, Exekutions-Kommandos"

Die Welt trauert um Fidel Castro. Vor allem jener Teil, der dem Sozialismus nahesteht. Die pathetischsten Worte findet der griechische Regierungschef Tsipras. Am meisten irritiert der neu gewählte US-Präsident Trump.

Fidel Castro und Che Guevara

INNENPOLITISCHES / GESELLSCHAFT / VERGANGENHEITSPOLITIK

Zu wenige Rücklagen für viele Sozialversprechen

"Sinkflug Deutschlands hat eingesetzt" - Experten warnen vor Finanzkollaps

Deutsche Rentenversicherung

Renten-Rücklage sinkt schneller als angenommen

Bundesregierung beschließt Enteignungen im Notfall

(Zur politischen Klasse)

Sag beim Abschied leise Servus

(Selbstverständnis der politischen Klasse)

Für Demokratie und Teilhabe: seid bereit!

von Michael Paulwitz

Frank-Walter Steinmeier

Der Verlegenheitskandidat

von Felix Krautkrämer

Wahl des Bundespräsidenten

Berliner Wagenburg

von Michael Paulwitz

Bundesregierung

Merkel kandidiert wieder für Kanzleramt

Die Ungewissheit ist beendet: Bundeskanzlerin Angela Merkel will wieder für den CDU-Vorsitz und das Kanzleramt kandidieren. Geht ihr Plan auf, könnte sie länger regieren als Konrad Adenauer.

Merkels Entscheidung – Das richtige Signal in unsicheren Zeiten?

Anne Will: Ich bin genauso das Volk!

(Zu Merkel)

Yes, she did it again!

Dr. Merkel und das gesammelte Schweigen

Von Heiner Flassbeck

Václav Klaus zu Massenmigration, Medien und Merkel: „Deutschland ist das Schlachtfeld Europas!“

(Auch ein Grund für die "Refugees Welcome"-Euphorie…)

Spätaussiedler distanzieren sich zunehmend von der Union

Einwanderer bevorzugen linke Parteien

(Hirnakrobatik der neuen Berliner Stadtregierung)

Rot-rot-grüne Erziehungsdiktatur

von Michael Paulwitz

Baden-Württembergs Innenminister rät von Selbstverteidigung ab

Nach Razzia gegen Salafisten

Wendt: „Äußerungen von Frau Özoguz sind grenzenlose Frechheit“

Ströbele soll Gauland als Alterspräsident verhindern

Grüne drängen ihren Parteiveteran Ströbele, noch einmal für den Bundestag anzutreten. Seine Mission: AfD-Vize Gauland von der Parlamentseröffnung verdrängen.

(Dazu…)

Grüner Ströbele tief im RAF-Sumpf

Mecklenburg-Vorpommern: Ein Facebook-Like für die AfD kostet den Ministerjob

Sascha Ott von der CDU wird nicht wie geplant Justizminister. Der Grund: Er hatte auf der Facebook-Seite der AfD Nordwestmecklenburg den Button "Gefällt mir" geklickt.

Privatsphäre in Deutschland

Schleichend zum Überwachungsstaat

BND-Gesetz, Vorratsdatenspeicherung, verschlüsselte Dienste wie WhatsApp knacken: In den vergangenen Monaten wurden in Deutschland teils drastische Überwachungsmaßnahmen auf den Weg gebracht.

Social Media

Wenn das Netz weiter lügt, ist mit Freiheit Schluss

Von Volker Kauder

CDU-Bouillon fordert Überwachung von WhatsApp

Volkstrauertag

Gesinnungskitsch

von Thorsten Hinz

(bizarr…)

Tipps zur Reinigung und Pflege der Stolpersteine

(Clara-Zetkin-Straße in Pirna; Grüne und SPD unterstützen Ehrung für KPD-Politikerin)

Clara bleibt

Vorläufiges Ende um Pirna-Posse

LINKE / KAMPF GEGEN RECHTS / ANTIFASCHISMUS / RECHTE

Kontrakultur Halle: die Gesichter der ersten Reihe

Kontrakultur Halle: die Gesichter der ersten Reihe

SPD-Mann nicht mehr im Landtag

„Endstation Rechts“ und „Storch Heinar“ vor der Pleite

Ehemaliges Rote Hilfe-Mitglied

Berliner Bezirksverordnete lassen Drohsel durchfallen

Nach Protesten

Innenminister Stahlknecht sagt Teilnahme an Diskussion über Rechtsruck ab

(Der "antifaschistisch" orientierte Publizist Butterwegge will Politiker werden…)

Linker Bundespräsidentenkandidat19

Butterwegge sagt Pegida und AfD Kampf an

Gleicke warnt vor Schönfärberei der Lage in Ost-Ländern

(Projekt Entdeutschung…)

Niedersachsen

Rot-Grün stellt Antrag auf mehrsprachigen Unterricht

SPD fordert Toleranzbekenntnis für Bayernhymne

Für den Einsatz gegen Kriminalität

Kriminalbeamte zeichnen Amadeu-Antonio-Stiftung aus

(Inszenierung des Holocaust gegen FPÖ-Bundespräsidentschaft)

Holocaustüberlebende warnt vor FPÖ-Bundespräsident

Trauriger Appell

Mit diesem bewegenden Video will eine 89-Jährige vor einem großen Fehler warnen

„Feine Sahne Fischfilet“

WDR bewirbt linksextreme Band

Mühlheim

Hintergrund ist Gründung von AfD-Ortsverband

„Bündnis gegen Rechts“ formiert sich

Angeblicher Neonazi-Überfall

Linkspartei-Politiker wegen Vortäuschens einer Straftat verurteilt

Nach Veröffentlichung von Beleidigung

Facebook sperrt Kolumnistin Anabel Schunke

AfD-Schatzmeister in Neukölln

Berliner Schule feuert Lehrer – weil er bei Pegida mitdemonstriert

Dresden verbietet Pegida-Chef Bachmann Demo-Leitung

Bayern

SPD-Bürgermeisterin feuert Nikolaus wegen Facebook-Like

Streiflicht

Soziale Ächtung als Druckmittel

von Dieter Stein

Hundertschaft im Einsatz

Linksextremisten behindern Rettungseinsatz

(Antidemokratische Gerichtsurteile)

AfD

Plakatzerstörung als Meinungsfreiheit

von Felix Krautkrämer

Unterhaching

Mutmaßliche Linksextremisten verwüsten AfD-Büro

Mutmaßlicher Linksextremist prügelt AfD-Politiker ins Krankenhaus

Frechen: Linksextreme schänden Ehrenmal

Berlin

Bekennerschreiben aufgetaucht

Gedenkorte für Kerstin Heisig und Uwe Lieschied geschändet

PKK-Ableger

130 Linksextremisten aus Deutschland kämpfen in Syrien

EINWANDERUNG / MULTIKULTURELLE GESELLSCHAFT

Deutschland zahlt XXL-Flüchtlingsharem 360.000 Euro im Jahr

Deutschland zahlt XXL-Flüchtlingsharem 360.000 Euro im Jahr

Syrischer Geschäftsmann reist mit vier Ehefrauen und 23 Kindern ein

Unterbringung und Betreuung

So viel kostet Deutschland ein Flüchtling

Knapp 900.000 Flüchtlinge sind im Jahr 2015 nach Deutschland gekommen - überwiegend aus Syrien. In diesem Jahr werden weniger als 300.000 Menschen erwartet, die hierzulande Schutz suchen. Besonders die Städte ächzen unter den damit verbundenen Kosten.

Hamburg

Flüchtlingshilfe Integration teurer als geplant

Polizei enttarnt fast tausend minderjährige Asylbewerber als Erwachsene

(Nun Landtags-Beratung…)

Karben

"Flüge schon gebucht"

Schülerin aus Klasse geholt und abgeschoben

(Linke Funktionäre sind "geschockt")

Abschiebung aus Schule in Karben

Beuth rechtfertigt Abschiebung

Wie SPD, Linke und Grüne Abschiebungen verhindern

»Wir haben die Pflicht zu helfen« – Im Gespräch mit Lothar Fritze

Gauck in Offenbach

Bundespräsident kommt nach Offenbach

Gauck will mit Schülern über Zusammenleben in Deutschland reden. Der Besuch ist in diesem Jahr schon die zweite hohe Anerkennung für die Integrationsleistung der Stadt.

Bundespräsident Gauck in Offenbach

Staatsbesuch in der Hauptstadt der Integration

Besuch in Offenbach zum Thema Integration

Berlin

Flüchtlingsamt: Mitarbeiter prangern chaotische Zustände an

(Der nächste Sympathieträger…)

Firas Alshater macht Videos und hat Buch geschrieben

Vom Flüchtling zum YouTube-Comedian

"Islamic State of Germany"

Trump-Lager zeigt islamisches Deutschland

Steine auf Polizisten

Ungarn verurteilt illegalen Einwanderer zu zehn Jahren Haft

Studie

Islamisten kehren nach Deutschland zurück, „um sich zu erholen“

Aus Rücksicht auf moslemische Einwanderer

Immer mehr Schulen in Neuss verbannen Schweinefleisch

„Wirtschaftliche Entscheidung“

Woolworth-Filiale räumt Weihnachtsartikel

Offenbach

Fraktion forderte Bericht über städtische Einrichtungen

AfD-Vorstoß zu christlichen Traditionen in Kitas abgelehnt

Tagen hinter Knastmauern

AfD findet vielerorts keine Versammlungsräume mehr

Westen waren keine Uniform

Mitglieder der „Scharia-Polizei“ freigesprochen

Islamist schlich sich beim Verfassungsschutz ein

(Rassismus gegen Deutsche)

So schlimm war der Rassismus in Deutschland seit 1945 noch nie

Gestiegene Kriminalität

Im Westen nichts Neues – oder doch? In den Straßen von Freiburg

Sicherheitsvorkehrungen

Mehr Polizisten, Personenkontrollen, Taschenverbote: Weihnachtsmärkte rüsten kräftig auf

Verlogene feministische Erklärungsmuster

Zu den Hintergründen von sexuellen Übergriffen

(Sexuelle Belästigungen und Polizeiarbeit)

Polizeiermittlungen

„Anzeige bringt nichts“ und: „Ja, wir haben Tat verschwiegen“

von Martina Meckelein

Phantombild nach Überfall in der Düsseldorfer Altstadt

Polizei sucht diesen Mann wegen Missbrauchs einer über 80-Jährigen

Prozess in Hamburg

Freispruch nach Silvester-Übergriffen: Opfer fühlt sich wehrlos

Razzien gegen mutmaßlich kriminelle Tschetschenen

Zelle zu klein: Rumänischer Straftäter bleibt in Deutschland

Bericht des Justizministeriums

Nordafrikaner beschmieren Haftzellen mit Kot und Blut

Brutaler Angriff in Jülich

Familien-Fehde soll Attacke bei Fußballspiel ausgelöst haben

Kiel

Türke schlägt Polizisten krankenhausreif – Staatsanwaltschaft sieht keinen Haftgrund

(Türkischer Migrationshintergrund)

Düren

Zehn verletzte Polizisten

Gewaltexzess nach Streit über falsch geparktes Auto

Niedersachsen

Frau am Strick fast zu Tode geschleift

Versuchter Mord

Hameln: Zweijähriger saß mit im Auto

("Südländisches Aussehen")

Räuberische Erpressung – Offenbach

Angetanzt, begrapscht und bedrängt

Sexuelle Übergriffe bei Jugendfeier in Münchner Rathaus

Baby aus Kinderwagen gehoben

Polizei sucht brutalen Räuber

KULTUR / UMWELT / ZEITGEIST / SONSTIGES

Erstmalig

Hamburg will Vermieter enteignen und Wohnungen zwangssanieren

Meinung

Zwangsbeglücktes Sanieren

von Lukas Steinwandter

Mehr gleich besser?

Deutschland verfällt dem Dämmwahn

Konflikt

Denkmalschutz kann auch zerstören

Eigentümer historischer Objekte im Raum Höchstadt wollen oder können Auflagen nicht erfüllen und tun nichts für deren Erhalt.

(Bundesweite Gefahr von Flächenabrissen)

Historische Fassaden in Pfaffenhofen

Denkmalschützer fürchten um Gesicht der Stadt

In Pfaffenhofen sorgen sich Bürger um historische Fassaden in der Altstadt. Sie befürchten, dass der Denkmalschutz gerade am zentralen Platz, dem Hauptplatz, zunehmend unterlaufen werden könnte. Gefährdet sind historische Fassaden, deren Häuser generalsaniert wurden.

Berlin: Rot-Rot-Grün plant deutsch-arabische Schule

JF-TV

„Demo für Alle“: Hessische Verhältnisse

Badengegangene Bildung Baden-Württemberg

Inklusion statt Bildung: Die Schüler in Brandenburg und Sachsen sind am besten, Bremen und Baden-Württemberg bilden das Schlusslicht. In Brandenburg und Sachsen sitzen kaum Kinder von Einwanderern in den Schulen, in Bremen jedes zweite.

(Dazu…)

Sensationsrede des Monats! Linkes Denken ist utopie-besoffen. Jörg Meuthen AFD

Bielefeld

9,5 Prozent Wahlbeteiligung

Studentenausschuß fordert Gender-Toiletten

Suche nach Gegenstrategie

Evangelische Kirche warnt vor Gender-Gegnern

Die Manipulation der Massenmedien

Quer-denken.tv

(Thema Ausgrenzung und Medien)

Mit dir tanze ich nicht

von Dieter Stein

(PC-Wächter…)

Sprachpolizei warnt vor verbalen Tretminen

von Felix Krautkrämer

„Orientierungshilfe für die Praxis“

Österreich: Presserat gibt Tips für Flüchtlings-Berichterstattung

Nach Vorwürfen der „Mitschuld“ an Trump-Sieg

Facebook will verstärkt gegen Falschmeldungen vorgehen

Christopher Lasch vs. Michael Seemann: Blinde Elite und globale Klasse

Strategische Schneisen (1): Entkoppelung

Paradigmenwechsel

Die Entwicklung einer Wirtschaft der Fürsorge

(Deutsche Bischöfe auf dem Tempelberg)

Bekenntnis oder Unterwerfung

von Dieter Stein

Warnt vor Rechtspopulismus

EKD-Ratsvorsitzender verteidigt Auftritt ohne Kreuz

An der Schlosskirche in Wittenberg

Dänischer Künstler klebt seinen Penis an Luthers Thesen-Tür

Bremer Kirche

Muezzin soll mit „Allahu Akbar“ christlichen Gottesdienst eröffnen

Muslimas als Zielgruppe

Dolce & Gabbana bringt Luxus-Kopftücher für Muslimas auf den Markt. Das Thema schlägt hohe Wellen – haben Modelabels einen neuen Markt gefunden? Noch zeigen sich Fashion-Häuser zögerlich.

Niederlande

Angebliches Rassismus-Symbol

200 Festnahmen bei Protesten gegen „Zwarten Pieten“

(Seichte Beruhigungs-Komödie…)

Komödie "Willkommen bei den Hartmanns"

Ziemlich beste Flüchtlingsfreunde

Der Regisseur Simon Verhoeven präsentiert in "Willkommen bei den Hartmanns" eine Kinokomödie zur deutschen Flüchtlingskrise - mit viel Krawall und ein paar bizarren Fehlgriffen, aber ehrfurchtgebietendem Mut zur politischen Aktualität.

Pöbeln bis der Arzt kommt

Stark zunehmende Gewalt in Notaufnahmen

(Dazu…)

Gewalt in den Notaufnahmen

Kommentar zur Gewalt in den Notaufnahmen

Maler Gerhard Richter rechnet mit Merkels Flüchtlingspolitik ab

(Neue Prüderie)

Babenhausen

Kunst wird aus Rathaus verbannt

Ist dieses Bild „potenziell frauenfeindlich“?

Trug sie es für Adolf Hitler?

Eva Brauns Höschen versteigert

Zika-Virus: Grünes Licht für Freilandtest mit Gentechnik-Mücken in Florida

Schmelzende Eisdecke könnte Schadstoffe aus dem Kalten Krieg freilegen

In den 60er Jahre wurde in Grönland ein militärischer Stützpunkt unter dem Eis aufgegeben. Eine internationale Studie mit Beteiligung der Universität Zürich zeigt nun: Durch den Klimawandel könnten gefährliche Abfallstoffe wieder an die Oberfläche gelangen, die eigentlich als für immer unter dem Eisschild begraben betrachtet wurden.

Schutz der Meere

Barbara Meier taucht nach Geisternetzen

Berlin - Ungewohntes Terrain für Barbara Meier (30): Das Model hat den Laufsteg gegen die Schiffsplanke und das Abendkleid gegen den Taucheranzug getauscht und alte und kaputte Fischernetze aus der Ostsee geholt.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

LVDC. —

LVDC. — LVDC. —

LVDC. —

Japan had a one-year strategic reserve of oil. Its stark choice was either run out of oil, fuel, and scrap steel over 12 months or go to war while it still had these resources. The only other potential source of oil for Japan was the distant Dutch East Indies, today Indonesia.

Japan had a one-year strategic reserve of oil. Its stark choice was either run out of oil, fuel, and scrap steel over 12 months or go to war while it still had these resources. The only other potential source of oil for Japan was the distant Dutch East Indies, today Indonesia.

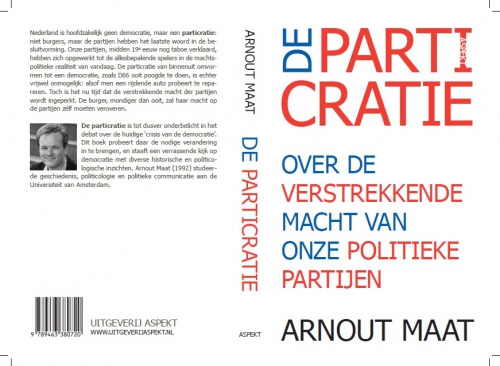

De Particratie (Aspekt 2016) is een werk van de aanstormende intellectueel Arnout Maat. Vanuit zijn achtergrond in geschiedenis, politicologie en politieke communicatie presenteert hij een relaas over het huidige politieke bestel. De essentie is dat politieke partijen al een eeuw lang een véél grotere rol spelen in de representatieve democratie dan ooit door onze grondwet is bedoeld. “De particratie van binnenuit omvormen to een democratie, zoals D66 ooit poogde te doen, is onmogelijk: alsof men een rijdende auto probeert te repareren”, zo vat Maat zijn relaas op de achterflap samen.

De Particratie (Aspekt 2016) is een werk van de aanstormende intellectueel Arnout Maat. Vanuit zijn achtergrond in geschiedenis, politicologie en politieke communicatie presenteert hij een relaas over het huidige politieke bestel. De essentie is dat politieke partijen al een eeuw lang een véél grotere rol spelen in de representatieve democratie dan ooit door onze grondwet is bedoeld. “De particratie van binnenuit omvormen to een democratie, zoals D66 ooit poogde te doen, is onmogelijk: alsof men een rijdende auto probeert te repareren”, zo vat Maat zijn relaas op de achterflap samen.

In a way, Apollo should not exist on Cyprus, or only in later times, if he was Dorian or entered the Greek world after the collapse of the Bronze Age societies. Cyprus, the large island that bridged the sea between Southern Anatolia and Western Syria, was inhabited by a native population; Greeks arrived at the very end of the Mycenaean period. They must have been Mycenaean Greeks who were displaced by the turmoil at the time when their Greek empire was crumbling. They brought with them their language, a dialect that was akin to the dialect of Arcadia in the Central Peloponnese to where Mycenaeans retreated from the invading Dorians, and they brought with them their writing system, a syllabic system closely connected with Linear A and B that quickly developed its own local variation and survived until Hellenistic times; then it was ousted by the more convenient Greek alphabet. The long survival of this system shows that, after its importation in the eleventh century BCE, Cypriot culture was very stable and only slowly became part of the larger Greek world. There was no later Greek immigration, either large-scale or modest, during the Iron Age: when Phoenicians immigrated in the eighth century, Cypriot culture, if anything, turned to the Near East. It is only plausible to assume that the Mycenaean settlers also brought their cults and gods with them: thus, the gods and festivals attested in the Cypriot texts are likely to reflect not Iron Age Greek religion but the Mycenaean heritage imported at the very end of the Bronze Age.

In a way, Apollo should not exist on Cyprus, or only in later times, if he was Dorian or entered the Greek world after the collapse of the Bronze Age societies. Cyprus, the large island that bridged the sea between Southern Anatolia and Western Syria, was inhabited by a native population; Greeks arrived at the very end of the Mycenaean period. They must have been Mycenaean Greeks who were displaced by the turmoil at the time when their Greek empire was crumbling. They brought with them their language, a dialect that was akin to the dialect of Arcadia in the Central Peloponnese to where Mycenaeans retreated from the invading Dorians, and they brought with them their writing system, a syllabic system closely connected with Linear A and B that quickly developed its own local variation and survived until Hellenistic times; then it was ousted by the more convenient Greek alphabet. The long survival of this system shows that, after its importation in the eleventh century BCE, Cypriot culture was very stable and only slowly became part of the larger Greek world. There was no later Greek immigration, either large-scale or modest, during the Iron Age: when Phoenicians immigrated in the eighth century, Cypriot culture, if anything, turned to the Near East. It is only plausible to assume that the Mycenaean settlers also brought their cults and gods with them: thus, the gods and festivals attested in the Cypriot texts are likely to reflect not Iron Age Greek religion but the Mycenaean heritage imported at the very end of the Bronze Age. In this reading, Apollo arrived in Greece with the Dorians who slowly moved into the Peloponnese and from there took over the towns of Crete, after the fall of Mycenaean power. Four centuries later, at the time of Homer and Hesiod, the god had become an established divinity in all of Greece, and a firm part of the narrative tradition of epic poetry. Such an expansion presupposes some degree of religious and cultural interpenetration and exchange throughout Greece during the Dark Ages. This somewhat contradicts the traditional image of this period as a time when the single communities of Greece were mostly turned towards themselves, with little connection with each other. But such a picture is based mainly on the rather scarce archaeological evidence; communication between people, even migration, does not always leave archaeological traces, and cults are based on myths and narratives, not on artifacts. And well before Homer, communications inside Greece opened up again, as shown by the rapid spread of the alphabet or of the so-called Proto-Geometric pottery style that both belong to the ninth or early eighth centuries BCE.

In this reading, Apollo arrived in Greece with the Dorians who slowly moved into the Peloponnese and from there took over the towns of Crete, after the fall of Mycenaean power. Four centuries later, at the time of Homer and Hesiod, the god had become an established divinity in all of Greece, and a firm part of the narrative tradition of epic poetry. Such an expansion presupposes some degree of religious and cultural interpenetration and exchange throughout Greece during the Dark Ages. This somewhat contradicts the traditional image of this period as a time when the single communities of Greece were mostly turned towards themselves, with little connection with each other. But such a picture is based mainly on the rather scarce archaeological evidence; communication between people, even migration, does not always leave archaeological traces, and cults are based on myths and narratives, not on artifacts. And well before Homer, communications inside Greece opened up again, as shown by the rapid spread of the alphabet or of the so-called Proto-Geometric pottery style that both belong to the ninth or early eighth centuries BCE.

Kontrakultur Halle: die Gesichter der ersten Reihe

Kontrakultur Halle: die Gesichter der ersten Reihe Deutschland zahlt XXL-Flüchtlingsharem 360.000 Euro im Jahr

Deutschland zahlt XXL-Flüchtlingsharem 360.000 Euro im Jahr

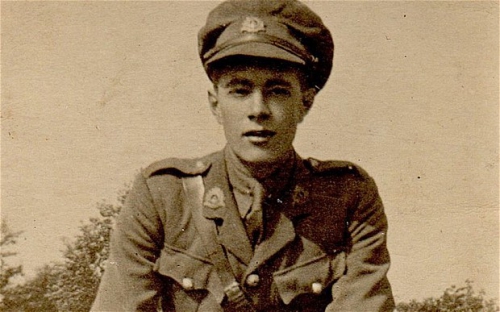

Today is the birthday of Henry Williamson (Dec. 1, 1895 – Aug. 13, 1977)—ruralist author, war historian, journalist, farmer, and visionary of British fascism.

Today is the birthday of Henry Williamson (Dec. 1, 1895 – Aug. 13, 1977)—ruralist author, war historian, journalist, farmer, and visionary of British fascism. Blackshirt sympathies are really a side-note with Williamson, as they are with Yeats, Belloc, and Wyndham Lewis. If he is largely forgotten today, this is not because he went to Nuremberg rallies (nobody forgets the Mitfords, after all), but rather because of the peculiar nature of his output. Apart from his war memoirs, most of his writing consists of highly detailed close observation, with little direct commentary on the world at large. (The newspaper column at the end of this article is a good example of Williamson’s work. Taken in large doses, such detail tends to become tedious.)

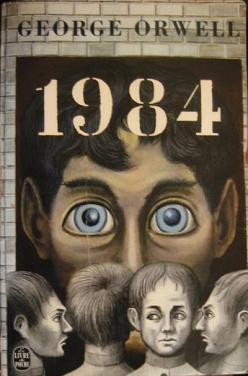

Blackshirt sympathies are really a side-note with Williamson, as they are with Yeats, Belloc, and Wyndham Lewis. If he is largely forgotten today, this is not because he went to Nuremberg rallies (nobody forgets the Mitfords, after all), but rather because of the peculiar nature of his output. Apart from his war memoirs, most of his writing consists of highly detailed close observation, with little direct commentary on the world at large. (The newspaper column at the end of this article is a good example of Williamson’s work. Taken in large doses, such detail tends to become tedious.) The romance of the country permeates his other fiction. In one novel after another, Orwell’s human characters rouse themselves, suddenly and unaccountably, to go tramping through meadows and hedgerows. In A Clergyman’s Daughter the title character gets amnesia and finds herself hop-picking in Kent. The superficially different stories in Nineteen Eighty-Four and Keep the Aspidistra Flying both have romantic episodes in which a couple go for long hikes through idyllic woods and fields, where they marvel and fornicate amongst the wonders of Mother Nature. The middle-aged narrator of Coming for Air spends much of the novel dreaming of fishing in the country ponds of his youth, but when he finally takes his rod and seeks down his old haunts, he finds that exurbia has encroached and his fishing-place is now being used as a latrine and rubbish-tip by a local encampment of beatnik nature-lovers.

The romance of the country permeates his other fiction. In one novel after another, Orwell’s human characters rouse themselves, suddenly and unaccountably, to go tramping through meadows and hedgerows. In A Clergyman’s Daughter the title character gets amnesia and finds herself hop-picking in Kent. The superficially different stories in Nineteen Eighty-Four and Keep the Aspidistra Flying both have romantic episodes in which a couple go for long hikes through idyllic woods and fields, where they marvel and fornicate amongst the wonders of Mother Nature. The middle-aged narrator of Coming for Air spends much of the novel dreaming of fishing in the country ponds of his youth, but when he finally takes his rod and seeks down his old haunts, he finds that exurbia has encroached and his fishing-place is now being used as a latrine and rubbish-tip by a local encampment of beatnik nature-lovers.