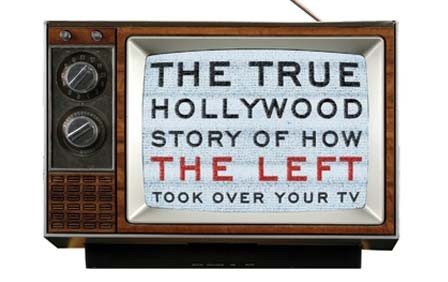

« L’une des tendances les plus répandues dans la culture occidentale au 21e siècle est presque devenue une obsession aux États-Unis : « l’histoire hollywoodienne ». Les studios privés de Los Angeles dépensent des centaines de millions de dollars pour confectionner sur mesure des événements historiques afin qu’ils conviennent au paradigme politique prédominant. » (Patrick Henningsen, Hollywood History: CIA Sponsored “Zero Dark Thirty”, Oscar for “Best Propaganda Picture”)

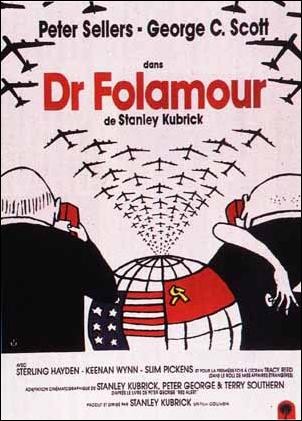

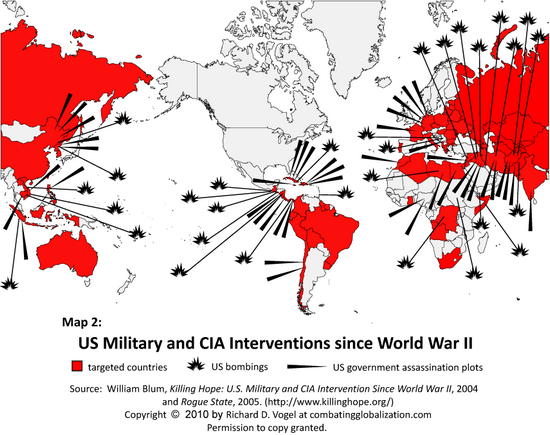

Black Hawk Dawn, Zero Dark Thirty et Argo, ne sont que quelques unes des productions récentes démontrant comment l’industrie cinématographique actuelle promeut la politique étrangère étasunienne. Le 7e art a toutefois été utilisé depuis le début de 20e siècle et la coopération d’Hollywood avec le département de la Défense, la CIA et d’autres agences gouvernementales n’est pas une nouvelle tendance.

En laissant Michelle Obama présenter l’Oscar du meilleur film, Argo de Ben Affleck, l’industrie a montré sa proximité avec Washington. Selon Soraya Sepahpour-Ulrich, Argo est un film de propagande occultant l’horrible vérité à propos de la crise des otages en Iran et conçu pour préparer l’opinion publique à une confrontation prochaine avec l’Iran.

« Ceux qui s’intéressent à la politique étrangère savent depuis longtemps qu’Hollywood reflète et promeut les politiques étasuniennes (déterminées par Israël et ses sympathisants). Ce fait a été rendu public lorsque Michelle Obama a annoncé le gagnant de l’Oscar du meilleur film, Argo, un film anti-iranien extrêmement propagandiste. Dans le faste et l’enthousiasme, Hollywood et la Maison-Blanche ont révélé leur pacte et envoyé leur message à temps pour les pourparlers relatifs au programme nucléaire iranien […]

Hollywood promeut depuis longtemps les politiques étasuniennes. En 1917, lors de l’entrée des États-Unis dans la Première Guerre mondiale, le Committee on Public Information (Comité sur l’information publique, CPI) a enrôlé l’industrie cinématographique étasunienne pour faire des films de formation et des longs métrages appuyant la “cause”. George Creel, président du CPI, croyait que les films avaient un rôle à jouer dans “la diffusion de l’évangile américaniste aux quatre coins du globe”.

Le pacte s’est fortifié durant la Seconde Guerre mondiale […] Hollywood contribuait en fournissant de la propagande. En retour, Washington a utilisé des subventions, des dispositions particulières du plan Marshall et son influence générale après la guerre pour forcer l’ouverture des marchés cinématographiques européens réfractaires […]

Alors qu’Hollywood et la Maison-Blanche s’empressent d’honorer Argo et son message propagandiste, ils occultent impudemment et délibérément un aspect crucial de cet événement “historique”. Le clinquant camoufle un fait important, soit que les étudiants iraniens ayant pris le contrôle de l’ambassade des États-Unis à Téhéran ont révélé au monde entier l’horrible secret d’Israël. Des documents classés “secrets” ont révélé les activités de LAKAM. Créé en 1960, LAKAM était un réseau israélien assigné à l’espionnage économique aux États-Unis et affecté à la “collecte de renseignement scientifique aux États-Unis pour le compte de l’industrie de la défense israélienne”. » (Soraya Sepahpour-Ulrich Oscar to Hollywood’s “Argo”: And the Winners are … the Pentagon and the Israel Lobby)

Pour un véritable compte rendu de la crise des otages en Iran, une opération clandestine de la CIA, Mondialisation.ca vous recommande la lecture d’un article de Harry V. Martin publié en 1995, The Real Iranian Hostage Story from the Files of Fara Mansoor et dont voici un extrait:

« Farah Mansour est un fugitif. Non, il n’a enfreint aucune loi aux États-Unis. Son crime est de connaître la vérité. Ce qu’il a à dire et les documents qu’il possède sont l’équivalent d’un arrêt de mort pour lui. Mansour est un Iranien ayant fait partie de l’establishment en Iran bien avant la crise des otages en 1979. Ses archives contredisent la soi-disant théorie de la “surprise d’octobre” voulant que l’équipe Ronald Reagan-George Bush ait payé les Iraniens pour qu’ils libèrent les 52 otages étasuniens seulement après les élections présidentielles de novembre 1980 […]

Détenant des milliers de documents pour appuyer sa version des faits, Mansour affirme que la “crise des otages” était un “outil de gestion” politique créé par la faction pro-Bush de la CIA et implanté à l’aide d’une alliance a priori avec les fondamentalistes islamiques de Khomeini. Il dit que l’opération avait deux objectifs :

- Garder l’Iran intact et sans communistes en donnant le contrôle absolu à Khomeini

- Déstabiliser l’administration Carter et mettre George Bush à la Maison-Blanche » (Harry V. Martin, The Real Iran Hostage Crisis: A CIA Covert Op)

Zero Dark Thirty est une autre œuvre de propagande du grand écran ayant soulevé un tollé plus tôt cette année. Le film exploite les événements affreux du 11-Septembre afin de présenter la torture comme un mal efficace et nécessaire :

« Zero Dark Thirty est troublant pour deux raisons. D’abord et avant tout le film laisse le spectateur avec la fausse impression que la torture a aidé la CIA à trouver la cachette de Ben Laden au Pakistan. Ensuite, il ignore à la fois l’illégalité et l’immoralité de l’utilisation de la torture comme technique d’interrogation.

Le thriller s’ouvre sur ces mots : « basé sur des témoignages d’événements réels ». Après nous avoir montré des séquences des horribles événements du 11-Septembre, le film passe à une longue représentation explicite de la torture. Le détenu, Ammar, est soumis à la simulation de noyade, mis dans des positions douloureuses, privé de sommeil et enfermé dans une petite boîte. En réaction à la torture, il divulgue le nom du messager qui mène finalement la CIA à l’endroit où se trouve Ben Laden et à son assassinat. C’est peut-être du bon cinéma, mais c’est inexact et trompeur. (Marjorie Cohn, “Zero Dark Thirty”: Torturing the Facts)

Plus tôt cette année les prix Golden Globe ont suscité les critiques de certains analystes dénonçant la macabre « célébration hollywoodienne de l’État policier » et avançant que le véritable gagnant des Golden Globe était le complexe militaro-industriel :

« Homeland a gagné les prix de meilleure série télévisée, du meilleur acteur et de la meilleure actrice. L’émission EST très divertissante et illustre certains défauts du système MIIC (complexe militaire, industriel et du renseignement).

Argo a reçu le prix du meilleur film et du meilleur réalisateur. Ben Affleck a fait l’éloge de la CIA, que son film glorifie.

Le prix de la meilleur actrice est allé à Jessica Chastain pour son rôle dans Zero Dark Thirty, un film vilipendé pour sa propagande sur l’utilisation de la torture […]

Le complexe militaire, industriel et du renseignement joue un rôle de plus en plus envahissant dans nos vies. Dans les prochaines années nous allons voir des films axés sur l’utilisation de la technologie des drones dans le milieu policier et de l’espionnage aux États-Unis. Nous voyons déjà des films montrant comment les espions peuvent violer tous les aspects de notre vie privée, des parties de nos vies les plus intimes. En faisant des films et des séries télévisées célébrant ces propagations cancéreuses de l’État policier, Hollywood et les grands studios normalisent les idées qu’ils nous présentent, en mentant au public en créant régulièrement des histoires frauduleuses pour camoufler la réalité. (Rob Kall cité dans Washington’s Blog, The CIA and Other Government Agencies Dominate Movies and Television)

Tous ces liens troublants qu’entretient Hollywood ont été examinés dans un article détaillé publié par Global Research en janvier 2009. Lights, Camera… Covert Action: The Deep Politics of Hollywood (Lumières, caméra… action clandestine : La politique profonde d’Hollywood). L’article énumère un grand nombre de films en partie scénarisés à des fins de propagande par le département de la Défense, la CIA et d’autres agences gouvernementales. Il est intéressant de noter que le réalisateur Ben Affleck, gagnant de l’Oscar du meilleur film cette année, a coopéré avec la CIA en 2002 alors qu’il était en vedette dans La Somme de toutes les peurs.

Les auteurs Matthew Alford et Robbie Graham expliquent que comparativement à la CIA, le département de la Défense « a une relation “ouverte“, mais peu publicisée avec Tinseltown, [laquelle], quoique moralement douteuse et peu affichée, est au moins du domaine publique ». Alford et Graham citent un rapport de la CIA révélant l’influence tentaculaire de l’agence, non seulement dans l’industrie du cinéma mais également dans les médias, « entretenant des liens avec des reporters de toutes les grandes agences de presse, tous les grands journaux, hebdomadaires et réseaux de télévision du pays ». Ce n’est qu’en 1996 que la CIA a annoncé qu’elle « collaborerait désormais ouvertement aux productions d’Hollywood, supposément à titre strictement “consultatif“ » :

« La décision de l’agence de travailler publiquement avec Hollywood a été précédée par le rapport de 1991, « Task Force Report on Greater CIA Openness » (Rapport du groupe de travail sur une plus grande ouverture de la CIA), compilé par le nouveau « Groupe de travail sur l’ouverture » créé par le directeur de la CIA Robert Gates. Ironiquement, ce rapport discutait secrètement de la possibilité que l’Agence devienne moins secrète. Le rapport reconnaît que la CIA “entretient actuellement des liens avec des reporters de toutes les grandes agences de presse, tous les grands journaux, hebdomadaires et réseaux de télévision du pays“. Les auteurs du rapport notent que cela les a aidé “à transformer des ‘échecs du renseignement’ en ‘succès’ et a contribué à l’exactitude de nombreuses histoires“. Le document révèle par ailleurs que la CIA a par le passé “persuadé des journalistes de retarder, changer, retenir ou même laisser tomber des histoires qui auraient pu avoir des conséquences néfastes sur des intérêts en matière de sécurité nationale […] »

L’auteur de romans d’espionnage Tom Clancy a joui d’une relation particulièrement étroite avec la CIA. En 1984, Clancy a été invité à Langley après avoir écrit Octobre rouge, adapté au cinéma dans les années 1990. L’agence l’a invité à nouveau lorsqu’il travaillait sur Jeux de guerre (1992) et les responsables de l’adaptation cinématographique ont eu à leur tour accès aux installations de Langley. Parmi les films récents, on compte La Somme de toutes les peurs (2002), illustrant la CIA repérant des terroristes faisant exploser une bombe nucléaire en sol étasunien. Pour cette production, le directeur de la CIA George Tenet a lui-même fait faire une visite guidée du quartier général de Langley. La vedette du film, Ben Affleck, a lui aussi consulté des analystes de l’Agence et Chase Brandon a agi à titre de conseiller sur le plateau de tournage.

Les véritable raisons pour lesquelles la CIA joue le rôle de “conseiller“ dans toutes ces productions sont mises en relief par un commentaire isolé du codirecteur du contentieux de la CIA Paul Kelbaugh. En 2007, lors d’un passage dans un collège en Virginie, il a donné une conférence sur les liens de la CIA avec Hollywood, à laquelle a assisté un journaliste local. Ce dernier (qui souhaite conserver l’anonymat) a écrit un compte-rendu de la conférence relatant les propos de Kelbaugh sur le thriller de 2003, La Recrue, avec Al Pacino. Le journaliste citait Kelbaugh qui disait qu’un agent de la CIA était sur le plateau pour toute la durée du tournage prétextant agir comme conseiller, mais que son vrai travail consistait à désorienter les réalisateurs […] Kelbaugh a nié catégoriquement avoir fait cette déclaration. (Matthew Alford and Robbie Graham, Lights, Camera… Covert Action: The Deep Politics of Hollywood)

Durant la Guerre froide, l’agent Luigi G. Luraschi du Psychological Strategy Board (Bureau de stratégie psychologique, PSB) de la CIA était un cadre de Paramount. Il « avait obtenu l’accord de plusieurs directeurs de la distribution pour que l’on infiltre subtilement des “nègres bien habillés” dans les films, dont un “digne majordome nègre” avec des répliques “indiquant qu’il est un homme libre” ». Le but de ces changements était « de freiner la capacité des Soviétiques à exploiter le bilan médiocre de leurs ennemis relativement aux relations raciales et servait à créer une impression particulièrement neutre des États-Unis, toujours embourbés à l’époque dans la ségrégation raciale ». (Ibid.)

Les plus récentes productions cinématographiques primées confirment que la vision manichéenne du monde mise de l’avant par le programme de la politique étrangère étasunienne n’a pas changé depuis la Guerre froide. L’alliance Hollywood-CIA se porte bien et présente encore les États-Unis comme le « leader du monde libre » combattant « le mal » dans le monde entier :

L’ancien agent de la CIA Bob Baer nous a confirmé que l’imbrication entre Hollywood et l’appareil de sécurité nationale est toujours aussi étroite : « Il y a une symbiose entre la CIA et Hollywood ». Les réunions de Sun Valley donnent du poids à ses déclarations. Lors de ces rencontres annuelles en Idaho, plusieurs centaines de grands noms des médias étasuniens, incluant tous les directeurs des grands studios d’Hollywood, se réunissent afin de discuter d’une stratégie médiatique commune pour l’année suivante. (Ibid.)

Mondialisation.ca offre à ses lecteurs une liste d’articles sur ce sujet.

Contrairement à l’industrie cinématographique hollywoodienne, Mondialisation.ca ne subit aucune influence de l’appareil étasunien du renseignement et travaille d’arrache pied pour vous offrir la vérité plutôt que de la fiction et de la propagande.

Nous comptons uniquement sur l’appui de nos lecteurs afin de continuer à nous battre pour la vérité et la justice. Si vous désirez contribuer à la recherche indépendante, devenez membre ou faites un don! Votre appui est très apprécié.

Article original: Screen Propaganda, Hollywood and the CIA

SELECTION D’ARTICLES

En français :

Lalo Vespera, Zero Dark Thirty : Oscar de l’islamophobie radicale

Lalo Vespera, Zero Dark Thirty et masque de beauté

David Walsh, Démineurs, la cérémonie des oscars et la réhabilitation de la guerre en Irak

Samuel Blumenfeld, Le Pentagone et la CIA enrôlent Hollywood

Timothy Sexton, L’histoire d’Hollywood : la propagande pendant la deuxième guerre mondiale

Matthew Alford et Robbie Graham, La politique profonde de Hollywood

En anglais:

Patrick Henningsen, Hollywood History: CIA Sponsored “Zero Dark Thirty”, Oscar for “Best Propaganda Picture”)

Soraya Sepahpour-Ulrich Oscar to Hollywood’s “Argo”: And the Winners are … the Pentagon and the Israel Lobby

Harry V. Martin, The Real Iranian Hostage Story from the Files of Fara Mansoor

Rob Kall cited inWashington’s Blog, The CIA and Other Government Agencies Dominate Movies and Television

Marjorie Cohn, “Zero Dark Thirty”: Torturing the Facts

Matthew Alford and Robbie Graham, Lights, Camera… Covert Action: The Deep Politics of Hollywood

Wednesday, December 5, 2012, the Albanian Prime Minister Sali Berisha advocated granting Albanian citizenship to all Albanians, wherever they reside. This statement was made during a visit of the city of Vlora where the independence of the Albanian state was declared, only 100 years ago. At the time Albania had just liberated itself from Ottoman rule.

Wednesday, December 5, 2012, the Albanian Prime Minister Sali Berisha advocated granting Albanian citizenship to all Albanians, wherever they reside. This statement was made during a visit of the city of Vlora where the independence of the Albanian state was declared, only 100 years ago. At the time Albania had just liberated itself from Ottoman rule.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Hoewel het Westen in volle expansie probeert te blijven, als het moet zelfs

Hoewel het Westen in volle expansie probeert te blijven, als het moet zelfs  Par ailleurs, ce même

Par ailleurs, ce même

Ex: http://orientalreview.org/