Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

Geoffrey Miller

Spent: Sex, Evolution, and Consumer Behavior

New York: Viking, 2009

When I was asked to review this book, I half groaned because I was sure of what to expect and I also knew it was not going to broaden my knowledge in a significant way. From my earlier reading up on other, but tangentially related subject areas (e.g., advertising), I already knew, and it seemed more than obvious to me, that consumer behavior had an evolutionary basis. Therefore, I expected this book would not make me look at the world in an entirely different way, but, rather, would reaffirm, maybe clarify, and hopefully deepen by a micron or two, my existing knowledge on the topic. The book is written for a popular audience, so my expectations were met. Fortunately, however, reading it proved not to be a chore: the style is very readable, the information is well-organized, and there are a number of unexpected surprises along the way to keep the reader engaged.

When I was asked to review this book, I half groaned because I was sure of what to expect and I also knew it was not going to broaden my knowledge in a significant way. From my earlier reading up on other, but tangentially related subject areas (e.g., advertising), I already knew, and it seemed more than obvious to me, that consumer behavior had an evolutionary basis. Therefore, I expected this book would not make me look at the world in an entirely different way, but, rather, would reaffirm, maybe clarify, and hopefully deepen by a micron or two, my existing knowledge on the topic. The book is written for a popular audience, so my expectations were met. Fortunately, however, reading it proved not to be a chore: the style is very readable, the information is well-organized, and there are a number of unexpected surprises along the way to keep the reader engaged.

Coming from a humanities educational background, I was familiar with Jean Baudrillard’s treatment of consumerism through his early works: The System of Objects (1968), The Consumer Society: Myths and Structures

(1970), and For a Critique of the Political Economy of the Sign

(1972). Baudrillard believed that there were four ways an object acquired value: through its functional value (similar to the Marxian use-value); through its exchange, or economic value; through its symbolic value (the object’s relationship to a subject, or individual, such as an engagement ring to a young lady or a medal to an Olympic athlete); and, finally, through its sign value (the object’s value within a system of objects, whereby a Montblanc fountain-pen may signify higher socioeconomic status than a Bic ball-pen, or a Fair Trade organic chicken may signify certain social values in relation to a chicken that has been intensively farmed). Baudrillard focused most of his energy on the latter forms of value. Writing at the juncture between evolutionary psychology and marketing, Geoffrey Miller (an evolutionary psychologist) does the same here, except from a purely biological perspective.

The are three core ideas in Spent: firstly, conspicuous consumption is essentially a narcissistic process being used by humans to signal their biological fitness to others while also pleasuring themselves; secondly, this processes is unreliable, as humans cheat by broadcasting fraudulent signals in an effort to flatter themselves and achieve higher social status; and thirdly, this process is also inefficient, as the need for continuous economic growth has led capitalists since the 1950s to manufacture products with built-in obsolescence, thus fueling a wasteful process of continuous substandard production and continuous consumption and rubbish generation. In other words, we live in a world where insatiable and amoral capitalists constantly make flimsy products with ever-changing designs and ever-higher specifications so that they break quickly and/or cause embarrassment after a year, and humans, motivated by primordial mating and hedonistic urges that have evolved biological bases, are thus compelled to frequently replace their consumer goods with newer and better models — usually the most expensive ones they can afford — so that they can delude themselves and others into thinking that they are higher-quality humans than they really are.

Miller tells us that levels of fitness are advertised by humans along six independent dimensions, comprised of general intelligence, and the five dimensions that define the human personality: openness to experience, conscientiousness, agreeableness, stability, and extraversion. Extending or drawing from theories expounded by Thorstein Veblen and Amotz Zahavi (the latter’s are not mainstream), Miller also tells us that, because fraudulent fitness signaling is part and parcel of animal behavior, humans, like other animals, will attempt to prove the authenticity of their signals by making their signaling a costly endeavor that is beyond the means of a faker. Signaling can be rendered costly through its being conspicuously wasteful (getting an MA at Oxford), conspicuously precise (getting an MIT PhD), or a conspicuous badge of reputation (getting a Harvard MBA) that requires effort to achieve, is difficult to maintain, and entails severe punishment if forged. Miller attempts to highlight the degree to which these strategies are wasteful when he points out that, in as much as university credentials are a proxy for general intelligence, both job seekers and prospective employers could much more efficiently determine a job seeker’s general intelligence with a simple, quick, and cheap IQ test.

As expected, we are told here that signaling behavior becomes, according to experimental data, exaggerated when humans are what Miller calls “mating-primed” (on the pull). Also as expected, men and women exhibit different proclivities: males emphasizing aggression and openness to experience by performing impressive and unexpected feats in front of desirable females, and females emphasizing agreeableness through participation in, for example, charitable events. And again as expected, Miller tells us that while dumb, young humans engaging in fitness signaling will tend to emphasize body-enhancing consumption (e.g., breast implants, muscle-building powders, platform shoes), older, more intelligent humans, educated by experience on the futility of such strategies, instead emphasize their general intelligence, conscientiousness, and stability through effective maintenance of their appearance, via regular exercise, sensible diet, careful grooming, and tasteful fashion. Still, this strategy follows biologically-determined patters: as women’s physiognomic indicators of fertility (eye size; sclera whiteness; lip coloration, fullness, and eversion; breast size; etc.) peak in their mid twenties, older women will apply make-up and opt for sartorial strategies that compensate for the progressive fading of these traits, in a subconscious effort to indicate genetic quality and stability, as well as — as mentioned above — conscientiousness.

Less expected were some of the explanations for some human consumer choices: when a human purchases a top-of-the-line, fully featured piece of electronic equipment, be it a stereo or a sewing machine, the features are less important than the opportunity the equipment provides its owner to talk about them, and thus signal his/her intelligence through their detailed, jargon-laden enumeration and description. This makes perfect sense, of course, and reading it provided theoretical confirmation of the correctness of my decision in the 1990s, when, after noticing that I only ever used a fraction of all available features and functions in any piece of electronic equipment, I decided to build a recording studio with the simplest justifiable models by the best possible brands.

Even less expected for me where some of the facts outside the topic of this book. Miller, conscious of the disrepute into which the evolutionary sciences have fallen due to foaming-at-the-mouth Marxist activists — Stephen Jay Gould, Leon Kamin, Steven Rose, and Richard Lewontin — and ultra-orthodox nurture bigots in modern academia, makes sure to precede his discussion by describing himself as a liberal, and by enumerating a horripilating catalogue of liberal credentials (he classes himself as a “feminist,” for example). He also goes on to cite survey data that shows most evolutionary psychologists in contemporary academia are socially liberal, like him. It is a sad state of affairs when a scientist feels obligated to asseverate his political correctness in order to avoid ostracism.

Unusually, however, Miller seems an honest liberal (even if he contradicts himself, as in pp. 297-8), and is critical in the first chapters as well as in the later chapters of the Marxist death-grip on academic freedom of inquiry and expression and of the cult of diversity and multiculturalism. The latter occurs in the context of a discussion on the various possible alternatives to a society based on conspicuous consumption, which occupies the final four chapters of this book. Miller believes that the multiculturalist ideology is an obstacle to overcoming the consumer society because it prevents the expression of individuality and the formation of communities with alternative norms and forms of social display. This is because humans, when left to freely associate, tend to cluster in communities with shared traits, while multiculturalist legislation is designed to prevent freedom of association. Moreover, and citing Robert Putnam’s research (but also making sure to clarify he does not think diversity is bad), Miller argues that “[t]here is increasing evidence that communities with a chaotic diversity of social norms do not function very well” (p. 297). Since the only loophole in anti-discrimination laws is income, the result is that people are then motivated to escape multiculturalism is through economic stratification, by renting or buying at higher price points, thus causing the formation of

low-income ghettos, working-class tract houses, professional exurbs: a form of assortative living by income, which correlates only moderately with intelligence and conscientiousness.

. . .

[W]hen economic stratification is the only basis for choosing where to live, wealth becomes reified as the central form of status in every community — the lowest common denominator of human virtue, the only trait-display game in town. Since you end up living next to people who might well respect wildly different intellectual, political, social, and moral values, the only way to compete for status is through conspicuous consumption. Grow a greener lawn, buy a bigger car, add a media room . . . (p. 300)

This is a very interesting and valid argument, linking the evils of multiculturalism with the consumer society in a way that I had not come across before.

Miller’s exploration of the various possible ways we could explode the consumer society does get rather silly at times (at one point, Miller considers the idea of tattooing genetic trait levels on people’s faces; and elsewhere he weighs requiring consumers to qualify to purchase certain products, on the basis of how these products reflect their actual genetic endowments). However, when he eventually reaches a serious recommendation, it is one I can agree with: promoting product longevity. In other words, shifting production away from the contemporary profit-oriented paradigm of cheap, rapidly-obsolescing, throwaway products and towards the manufacture of high quality, long-lasting ones, that can be easily serviced and repaired. This suggests a return to the manufacturing standards we last saw during the Victorian era, which never fails to put a smile on my face. Miller believes that this can be achieved using the tax system, and he proposes abolishing the income tax and instituting a progressive consumption tax designed to make cheap, throwaway products more expensive than sturdy ones.

Frankly, I detest the idea of any kind of tax, since I see it today as a forced asset confiscation practiced by governments who are intent in destroying me and anyone like me; but if there has to be tax, if that is the only way to clear the world out of the perpetual inundation of tacky rubbish, and if that is the only way to obliterate the miserable businesses that pump it out day after day by the centillions, then let it mercilessly punish low quality — let it sadistically flog manufacturers of low-quality products with the scourging whip of fiscal law until they squeal with pain, rip their hair out, and rend their garments as they see their profits plummet at the speed of light and completely and forever disappear into the black hole of categorical bankruptcy.

If you are looking for a deadly serious, arid text of hard-core science, Spent is not for you: the same information can be presented in a more detailed, programmatic, and reliable manner than it is here; this book is written to entertain as much as it is to educate a popular audience. If you are looking for a readable overview, a refresher, or an update on how evolved biology interacts with marketing and consumption, and would appreciate a few key insights as a prelude to further study, Spent is an easy basic text. It should be noted, however, that his area of research is still in relative infancy, and there is here a certain amount of speculation laced with proper science. Therefore, if you are interested in this topic, and are an activist or businessman interested in developing more effective ways to market your message or products, you may want to adopt an interdisciplinary approach and read this alongside Jacques Ellul’s Propaganda: The Formation of Men’s Attitudes, Jean Baudrillard’s early works on consumerism, and some of the texts in Miller’s own bibliography, which include — surprise, surprise! — The Bell Curve: Intelligence and Class Structure in American Life

, by Richard Herrnstein and Charles Murray, and The Global Bell Curve: Race, IQ, and Inequality Worldwide

, by Richard Lynn, among others.

TOQ Online, August 14, 2009

(*) Article publié dans le dernier numéro de Rivarol (

(*) Article publié dans le dernier numéro de Rivarol (

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg Jure Vujić,avocat, diplomé de droit à la Faculté de droit d’Assas ParisII, est un géopoliticien et écrivain franco-croate. Il est diplomé de la Haute Ecole de Guerre „Ban Josip Jelačić“ des Forces Armées Croates et de l’Academie diplomatique croate ou il donne des conférences regulières en géopolitique et géostratégie. Il est l’auteur des livres suivants: „Fragments de la pensée géopolitique“ ( Zagreb, éditions

Jure Vujić,avocat, diplomé de droit à la Faculté de droit d’Assas ParisII, est un géopoliticien et écrivain franco-croate. Il est diplomé de la Haute Ecole de Guerre „Ban Josip Jelačić“ des Forces Armées Croates et de l’Academie diplomatique croate ou il donne des conférences regulières en géopolitique et géostratégie. Il est l’auteur des livres suivants: „Fragments de la pensée géopolitique“ ( Zagreb, éditions

1. The Genealogy of Modernity

1. The Genealogy of Modernity Lawrence encountered the effects of modernity—especially the Industrial Revolution—directly in his native Midlands. He saw how if affected people, generally for the worse. Again and again he sets his stories against the backdrop of the collieries. He saw the miners become increasingly dehumanized. Working in the earth, they become cut off from it and from themselves. They lived, but they did not flourish. Lawrence’s remarks about the Industrial Revolution, capitalism, and the condition of the miners put him quite close to the thought of Marx and other socialist writers. In fact, it would not be at all unreasonable to claim Lawrence as a kind of socialist. However, as we shall see, few socialists would wish to do so!

Lawrence encountered the effects of modernity—especially the Industrial Revolution—directly in his native Midlands. He saw how if affected people, generally for the worse. Again and again he sets his stories against the backdrop of the collieries. He saw the miners become increasingly dehumanized. Working in the earth, they become cut off from it and from themselves. They lived, but they did not flourish. Lawrence’s remarks about the Industrial Revolution, capitalism, and the condition of the miners put him quite close to the thought of Marx and other socialist writers. In fact, it would not be at all unreasonable to claim Lawrence as a kind of socialist. However, as we shall see, few socialists would wish to do so!

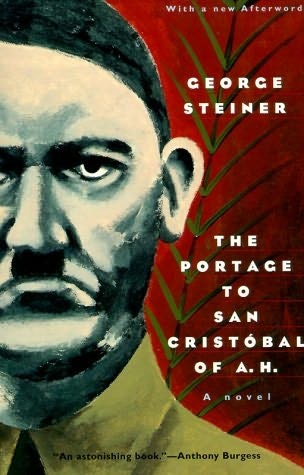

George Steiner’s novella, The Portage to San Cristobal of A. H., was published about three decades back and encodes a large number of the author’s non-fiction books which were released beforehand. This is especially pertinent to the analysis published in

George Steiner’s novella, The Portage to San Cristobal of A. H., was published about three decades back and encodes a large number of the author’s non-fiction books which were released beforehand. This is especially pertinent to the analysis published in

Ce jeune homme qui a fait de bonnes études, interrompues par les événements, travaille comme dactylo chez le notaire, s’emploie l’été chez un cultivateur, joue du piano le samedi soir dans les bals. Bref, il n’y a rien à lui reprocher, mais, tout de même, il n’est pas comme tout le monde : on le lui fait savoir. Pourtant, il est communiste, selon l’air du temps, mais à sa façon sans doute.

Ce jeune homme qui a fait de bonnes études, interrompues par les événements, travaille comme dactylo chez le notaire, s’emploie l’été chez un cultivateur, joue du piano le samedi soir dans les bals. Bref, il n’y a rien à lui reprocher, mais, tout de même, il n’est pas comme tout le monde : on le lui fait savoir. Pourtant, il est communiste, selon l’air du temps, mais à sa façon sans doute. Lieutenant Tenant est la première pièce jouée, en 1962… Une critique flatteuse de Jean-Jacques Gautier l’avait lancée et un reportage photo dans Paris-Match avait précipité Pierre sous les feux de la rampe (le système a parfois des faiblesses et laisse passer… Il ne peut pas tout contrôler, aussi rigide qu’il soit). Et voici que tout se gâte : après quelques semaines, le producteur trouve que la pièce est trop courte et lui demande d’ajouter une scène. Pierre refuse (on reconnaît là sa propension à être infréquentable !) Il n’a pas de vanité d’auteur, mais beaucoup d’orgueil et ne supportera jamais qu’on touche à ce qu’il écrit. Qu’à cela ne tienne, le producteur fait écrire la scène par un autre… ce que Pierre n’accepte pas, évidemment.

Lieutenant Tenant est la première pièce jouée, en 1962… Une critique flatteuse de Jean-Jacques Gautier l’avait lancée et un reportage photo dans Paris-Match avait précipité Pierre sous les feux de la rampe (le système a parfois des faiblesses et laisse passer… Il ne peut pas tout contrôler, aussi rigide qu’il soit). Et voici que tout se gâte : après quelques semaines, le producteur trouve que la pièce est trop courte et lui demande d’ajouter une scène. Pierre refuse (on reconnaît là sa propension à être infréquentable !) Il n’a pas de vanité d’auteur, mais beaucoup d’orgueil et ne supportera jamais qu’on touche à ce qu’il écrit. Qu’à cela ne tienne, le producteur fait écrire la scène par un autre… ce que Pierre n’accepte pas, évidemment.  Cet état de pauvreté consenti lui donnait une apparence un peu particulière qui le rendait encore infréquentable à une autre échelle : celle des relations sociales. Il allait en sandales, à grandes enjambées, le pantalon attaché avec une ficelle, un «anorak» informe jeté sur les épaules. Le luxe qu’il s’accordait, dès qu’il le pouvait, c’était l’opéra, un lieu où il faisait certainement sensation, mais quant au répertoire il le connaissait certainement mieux que la plupart des spectateurs qu’il y côtoyait.

Cet état de pauvreté consenti lui donnait une apparence un peu particulière qui le rendait encore infréquentable à une autre échelle : celle des relations sociales. Il allait en sandales, à grandes enjambées, le pantalon attaché avec une ficelle, un «anorak» informe jeté sur les épaules. Le luxe qu’il s’accordait, dès qu’il le pouvait, c’était l’opéra, un lieu où il faisait certainement sensation, mais quant au répertoire il le connaissait certainement mieux que la plupart des spectateurs qu’il y côtoyait. Tout cela ne fait pas un gros dossier de presse ! Et quand un journaliste aventureux chronique les Contes, encore aujourd’hui, il ne manque pas de prendre les précautions d’usage, disant que son œuvre pour adultes sent le soufre. Le jour où Jacques Chancel l’invita pour la célèbre émission Radioscopie, en 1979, il fut rappelé à l’ordre par la LICA… Gripari s’était livré à quelque plaisanterie saugrenue sur le racisme !

Tout cela ne fait pas un gros dossier de presse ! Et quand un journaliste aventureux chronique les Contes, encore aujourd’hui, il ne manque pas de prendre les précautions d’usage, disant que son œuvre pour adultes sent le soufre. Le jour où Jacques Chancel l’invita pour la célèbre émission Radioscopie, en 1979, il fut rappelé à l’ordre par la LICA… Gripari s’était livré à quelque plaisanterie saugrenue sur le racisme !