Derek Hawthorne

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

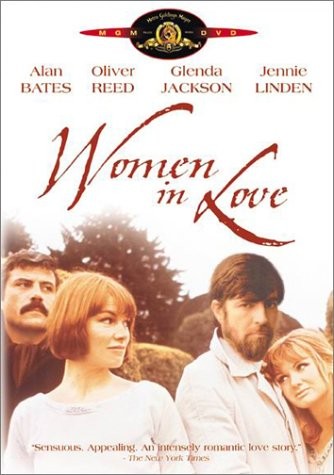

D. H. Lawrence’s greatest novel is also his most anti-modern. Written between April and October of 1916 in Cornwall, during some of the darkest days of the First World War, Women in Love

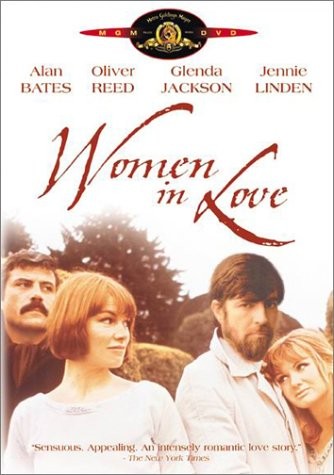

D. H. Lawrence’s greatest novel is also his most anti-modern. Written between April and October of 1916 in Cornwall, during some of the darkest days of the First World War, Women in Love was conceived as a sequel to The Rainbow. (Both novels were brilliantly filmed

was conceived as a sequel to The Rainbow. (Both novels were brilliantly filmed by Ken Russell.) Women in Love continues the story of Ursula Brangwen’s life, and the fulfillment she finds in a love affair with Rupert Birkin (who does not figure in The Rainbow at all). This relationship is, in fact, paired with another: that of Gudrun, Ursula’s sister (a very minor character in The Rainbow), and Gerald Crich, Birkin’s best friend. The novel follows the course of both relationships.

by Ken Russell.) Women in Love continues the story of Ursula Brangwen’s life, and the fulfillment she finds in a love affair with Rupert Birkin (who does not figure in The Rainbow at all). This relationship is, in fact, paired with another: that of Gudrun, Ursula’s sister (a very minor character in The Rainbow), and Gerald Crich, Birkin’s best friend. The novel follows the course of both relationships.

The connection between the two novels seems a tenuous one at best, however, and one can read and appreciate Women in Love without any knowledge at all of The Rainbow. This has a great deal to do with the dramatic difference in tone between the two. In a letter, Lawrence described the relationship between the two novels as follows: “There is another novel, sequel to The Rainbow, called Women in Love . . . this actually does contain the results in one’s soul of the war; it is purely destructive, not like The Rainbow, destructive-consummating.”

Women in Love is indeed “purely destructive”: it is grimly apocalyptic and misanthropic. There is little sense of the presence of nature this time: the novel moves almost entirely within the conscious and (more importantly) subconscious minds of its four main characters. And the backdrop is the ugly, human–built mechanicalness of the industrialized Midlands. It is easy to attribute the change in tone between the two novels as due to Lawrence’s horror at the war (“The war finished me,” he later said).

But one must not lose sight of the fact that the two novels do, in fact, tell one continuous story, and that the switch in tone is appropriate to what the second half of the story depicts: the fragmentary lives of individuals struggling to find fulfillment in the modern world. In his “Foreword” to the novel Lawrence wrote that it “took its final shape in the midst of the period of war, though it does not concern the war itself. I should wish the time to remain unfixed, so that the bitterness of the war may be taken for granted in the characters.” For Lawrence, as for Heidegger, the war was ultimately just an inevitable extension of the industrial age itself.

At the beginning of the story, Birkin is involved in an unhappy love affair with Hermione Roddice, the daughter of an aristocrat and a thinly-disguised portrait of Lady Ottoline Morrell. Birkin is already acquainted with Ursula professionally, as he is the local school inspector and she the school mistress. After they are brought closer together and love begins to grow between them, Birkin abandons Hermione. The memorable episode that precipitates the final break between them involves Hermione trying to bludgeon him to death with a lapis lazuli paperweight.

However, Birkin’s relationship with Ursula is, from the first, difficult in its own way. Much of the reason has to do with Birkin’s misanthropy and Schopenhauerian pessimism. At some level, Ursula sympathizes with Birkin’s views, but she is put off by his extraordinary vehemence, and, more importantly, seems to feel that if he would admit his love for her and fully surrender himself to their relationship he would be freed from his all-consuming hatred of the world. She is carrying on with life, in spite of everything, and eventually she succeeds in drawing him back into life.

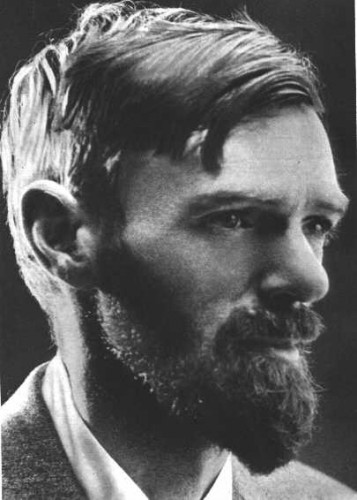

The character of Rupert Birkin is universally acknowledged to be a self-portrait of Lawrence, though it would be dangerous to assume that Lawrence has no critical distance from the character (or from himself, for that matter). Nevertheless, Birkin often speaks for Lawrence. Early in the novel Birkin declares that it would be much better if humanity “were just wiped out. Essentially they don’t exist, they aren’t there.” Later, in conversation with Ursula, Birkin declares:

“Humanity is a huge aggregate lie, and a huge lie is less than a small truth. Humanity is less, far less than the individual, because the individual may sometimes be capable of truth, and humanity is a tree of lies. And they say that love is the greatest thing: they persist in saying this, the foul liars, and just look at what they do! . . . It’s a lie to say that love is the greatest. . . . What people want is hate—hate and nothing but hate. And in the name of righteousness and love they get it. . . . If we want hate, let us have it—death, murder, torture, violent destruction—let us have it: but not in the name of love. But I abhor humanity, I wish it was swept away. It could go, and there would be no absolute loss, if every human being perished tomorrow. . . .”

“So you’d like everybody in the world destroyed?” said Ursula. . . .

“Yes truly. You yourself, don’t you find it a beautiful clean thought, a world empty of people, just uninterrupted grass, and a hare sitting up?”

The pleasant sincerity of his voice made Ursula pause to consider her own proposition. And it really was attractive: a clean, lovely, humanless world. It was the really desirable. Her heart hesitated and exulted. But still, she was dissatisfied with him.

If anything, in his own correspondence Lawrence goes further than Birkin. In a letter to his friend S. S. Koteliansky, dated September 4, 1916, while Lawrence was working on Women in Love, he declares:

I must say I hate mankind—talking of hatred, I have got a perfect androphobia. When I see people in the distance, walking along the path through the fields to Zennor, I want to crouch in the bushes and shoot them silently with invisible arrows of death. I think truly the only righteousness is the destruction of mankind, as in Sodom. . . . Oh, if one could but have a great box of insect powder, and shake it over them, in the heavens, and exterminate them. Only to clear and cleanse and purify the beautiful earth, and give room for some truth and pure living.

Where Women in Love is most interesting, however, is not in such outpourings of venom, but in Lawrence’s attempts to pinpoint why things have gone so disastrously wrong in the modern world. As have many other authors, Lawrence places a great deal of weight on the materialism and mechanism of industrialized modernity. Another, later, exchange between Birkin and Ursula is particularly revealing in this regard. The pair have just bought a chair at a flea market and Birkin states:

“When I see that clear, beautiful chair, and I think of England, even Jane Austen’s England—it had living thoughts to unfold even then, and pure happiness in unfolding them. And now, we can only fish among the rubbish-heaps for the remnants of their old expression. There is no production in us now, only sordid and foul mechanicalness.”

“It isn’t true,” cried Ursula, “Why must you always praise the past at the expense of the present? Really, I don’t think so much of Jane Austen’s England. It was materialistic enough, if you like—”

“It could afford to be materialistic,” said Birkin, “because it had the power to be something other—which we haven’t. We are materialistic because we haven’t the power to be anything else—try as we may, we can’t bring off anything but materialism: mechanism, the very soul of materialism.”

But why did Jane Austen’s England have the power to be something else? And what else did it have the power to be? For the answers to these questions we must, in essence, look back to The Rainbow. Jane Austen’s England still preserved some connection to the land—a sense of belonging to nature. What England then had the “power to be” was nothing grand and idealistic: it had the power simply to be its natural self. The people of Jane Austen’s England made and enjoyed beautiful objects—but these objects were an ornament to a life lived in relative closeness to the earth.

But why did Jane Austen’s England have the power to be something else? And what else did it have the power to be? For the answers to these questions we must, in essence, look back to The Rainbow. Jane Austen’s England still preserved some connection to the land—a sense of belonging to nature. What England then had the “power to be” was nothing grand and idealistic: it had the power simply to be its natural self. The people of Jane Austen’s England made and enjoyed beautiful objects—but these objects were an ornament to a life lived in relative closeness to the earth.

In the industrialized world of 1916, however, objects are all that human beings have. The object of life itself becomes the production and acquisition of objects. This by itself cannot, of course, provide any sense of “meaning in life,” and to fill this void we have introduced idealism and given to our materialism a moral veneer: we are making Progress, alleviating hunger and disease and want, promoting equality, and in general perfecting ourselves and the world through the marriage of science and commerce.

Gerald Crich and the Mastery of Nature

In Women in Love the coupling of industrial materialism with idealism is personified by Birkin’s friend Gerald Crich, son of the local colliery owner. On the train together, the two men speak of the modern world: “So you really think things are very bad?” Gerald asks. “Completely bad,” Birkin responds. Throughout the novel, Gerald is drawn to Birkin, fascinated by the man and his notions—yet he is repelled by him at the same time, and frightened. He encourages Birkin to explain what he means, and Birkin obliges him:

“We are such dreary liars. Our idea is to lie to ourselves. We have an ideal of a perfect world, clean and straight and sufficient. So we cover the earth with foulness; life is a blotch of labour, like insects scurrying in filth, so that your collier can have a pianoforte in his parlour, and you can have a butler and a motor-car in your up-to-date house, and as a nation we can sport the Ritz, or the Empire, Gaby Deslys and the Sunday newspapers. It is very dreary.”

But Gerald responds that he thinks the pianoforte represents “a real desire for something higher” in the collier’s life.

“Higher!” cried Birkin. “Yes. Amazing heights of upright grandeur. It makes him so much higher in his neighboring collier’s eyes. He sees himself reflected in the neighboring opinion, like in a Brocken mist, several feet taller on the strength of the pianoforte, and he is satisfied. He lives for the sake of that Brocken spectre, the reflection of himself in the human opinion.”

Material things and the zeal for material things do not lift up the average man. They merely produce what Christopher Lasch aptly called “the culture of narcissism,” and what Wendell Berry has called a “consumptive culture.” One of the absurdities of modern life is the pretence that human beings who have been reduced to the level of mere consumers are somehow more “advanced” than their ancestors.

But aside from man the consumer, what of man the producer? After all, someone has to produce all those pianofortes. This is where men like Gerald come in. Birkin asks Gerald what he lives for. Gerald answers: “I suppose I live to work, to produce something, in so far as I am a purposive being. Apart from that, I live because I am living.” Ursula remarks to Gudrun that Gerald has “got go, anyhow” and Gudrun replies, “The unfortunate thing is, where does his go go to, what becomes of it?” Ursula suggests, jokingly, that it “goes in applying the latest appliances!” This remark, however, is truer than she supposes.

The most brilliantly-written chapter of Women in Love is “The Industrial Magnate,” in which Lawrence depicts Gerald’s mastery of the mine. Gerald spends the first few years of his adult life wandering aimlessly, but always in hearty, masculine fashion: living the wild life of a student, becoming a soldier, then an adventurer. Always with Gerald there was an overweening curiosity and a desire truly to master something—a desire which masks a real, inner feeling of helplessness and lostness. He finds his true calling in running the mine, for there he believes he has found the meaning of life:

Immediately he saw the firm, he realized what he could do. He had to fight with Matter, with the earth and the coal it enclosed. This was the sole idea, to turn upon the inanimate matter of the underground, and reduce it to his will. . . . There were two opposites, his will and the resistant Matter of the earth. . . . He had his life-work now, to extend over the earth a great and perfect system in which the will of man ran smooth and unthwarted timeless, a Godhead in process.

By writing “Matter” with a capital M, Lawrence underscores the fact that for Gerald the mine is important not in itself but for what it represents. Gerald sees himself not merely as a colliery owner, but as a titanic being: a participant in the long, historical process of man’s divinization through the conquest of nature, now coming to full consummation in the industrial age.

But where has he gotten such ideas? Lawrence tells us that Gerald “refused to go to Oxford, choosing a German university,” and that he “took hold of all kinds of sociological ideas, and ideas of reform.” It is plain that Gerald has been exposed to a great deal of German philosophy. In depicting Gerald’s outlook on life, Lawrence seems to be blending ideas and terminology from three German philosophers: Fichte, Hegel, and Nietzsche.

Fichte and the Mastery of Nature

Lawrence writes that through Gerald’s domination of his will (or his ideals) over Matter “there was perfection attained, the will of mankind was perfectly enacted; for was not mankind mystically contradistinguished against inanimate Matter, was not the history of mankind just the history of the conquest of the one by the other?” The philosophy this is closest to is that of Fichte, though Lawrence is probably thinking of Hegel.

Fichte believed, essentially, that an objective world—an other standing opposed to ego—existed merely as an instrument for the expression of human will. Nature, or what Lawrence here calls “Matter,” exists as something that must be overcome and transformed by human beings according to human ideals. In doing so, human beings realize themselves. All of human history for Fichte, indeed all of reality, is the unending imposition of the ideal on the real, or the transformation of material otherness into an image of human will.

Even though Fichte’s philosophy, at first glance, appears to be something novel, in fact in a sense it is (and was) nothing new at all: it is the underlying metaphysics of modernity laid bare. In the modern world, again, human beings essentially relate to nature as raw material that must be forced to fit human designs or interests—or at best as a mere background for human action. Further, time is conceived in linear fashion and history as a movement from darkness to light, from primitivism to progressivism.

The humanism of the Renaissance becomes, in the modern period, anthropocentrism. Man is a titanic being without any natural superior, whose vocation is to better the world and other men. It is pointless to ask when, exactly, these modern attitudes took hold. In part, they are an outgrowth of Christian monotheism, which taught the idea that the earth and all its contents has been given to man by God for his exclusive use.

Renaissance humanism, which was in many ways a kind of neo-pagan revolt against Christianity, celebrated the ideal of man as Magus, and as a kind of mini-God here on earth. In part, though these Renaissance ideas were bound up with the revival of Hermetic occultism, they paved the way for the scientific revolution represented by men such as Francis Bacon.

By that point in history, belief—real belief—in the God of monotheism was dying, at least among the intelligentsia, who veered more and more toward abstract conceptions of divinity which had little to do with human life. God, in other words, had become irrelevant and human beings found themselves alone in this world that had been given to them for their mastery, with nothing watching from above. It was only a matter of time before man would declare himself God, as Fichte virtually does.

Hegel’s Idealism

Hegel took over Fichte’s ideas and, among other things, amplified them with a theological interpretation. God, for Hegel, is pure self-related Idea which becomes real and concrete in the world through human self-awareness—a self-awareness achieved primarily through the analysis and mastery of nature, as well as through art, religion, and philosophy.

Although Hegel insisted that he had not meant to make man God, a great many of his followers and detractors saw that this is precisely what his philosophy had done. The “young Hegelian” Ludwig Feuerbach saw this and in his influential work The Essence of Christianity (1841) declared that God was, in fact, nothing but an ideal projection of human consciousness, a stand-in, in fact, for humanity itself.

The Hegelian (or, perhaps, young Hegelian) element in Gerald’s metaphysics comes in when Lawrence tells us that Gerald found his “eternal and his infinite” in the endless cycle of machine production. God, as Hegel learned from Aristotle, is an eternal act. The never-ending cycles of modern, industrial production—the apex of man’s mastery of nature—becomes, for Gerald, God incarnate: “the whole productive will of man was the Godhead.”

Nietzsche, Hegel, and the End of History

What seems Nietzschean here is simply the insistence on Will. In allowing himself to be used as an instrument of the “productive will of man” Gerald believes that he is aggrandizing his own personal power. However, as I noted earlier, in believing so Gerald is deceiving himself, and in the end “the God-motion, this productive repetition ad infinitum” simply burns him away in a cold fire. However, there is more to Gerald’s Nietzscheanism than this.

The relation of Nietzsche to Hegel is a complex one, but it can be boiled down in the following way. Hegel believed that in the modern period history had, in effect, ended. This assertion seems nonsensical if we make the mistake of confusing history with time. Of course, Hegel did not think time had stopped. He merely believed that the story of mankind had come to an end in the modern age, because it was in the modern, post-Christian age that mankind came to realize its true nature as radically self-determining (and other-determining, as well). With this realization of radical human freedom, and the realization that man actualizes God in the world, Hegel believed that essentially all the important questions and controversies of human history had been answered. The destiny of man was to live in more or less liberal societies, under more or less democratic states, and to practice more or less humanistic versions of Christianity. And in this condition mankind would continue to exist and prosper.

For Nietzsche, on the other hand, the end of history meant the death of everything that ennobles the human race. Without anything to struggle over or to believe in so strongly that one would be willing to fight and die for it, humanity would sink to the level of what Nietzsche called the Last Man, Homo economicus: the man whose aspirations do not rise above material comfort, safety, and security. The only hope was the arrival of the Overman, who would create new values, new systems of belief, and initiate new conflicts among human beings. In short, the Overman would re-start history. Nietzsche’s writings, in their trenchant critique of all Western beliefs and values, can be seen as an attempt to actually hasten the collapse of the modern world and usher in the Overman.

For Nietzsche, on the other hand, the end of history meant the death of everything that ennobles the human race. Without anything to struggle over or to believe in so strongly that one would be willing to fight and die for it, humanity would sink to the level of what Nietzsche called the Last Man, Homo economicus: the man whose aspirations do not rise above material comfort, safety, and security. The only hope was the arrival of the Overman, who would create new values, new systems of belief, and initiate new conflicts among human beings. In short, the Overman would re-start history. Nietzsche’s writings, in their trenchant critique of all Western beliefs and values, can be seen as an attempt to actually hasten the collapse of the modern world and usher in the Overman.

Nietzsche’s Will to Power

Essentially, Gerald Crich represents the Nietzschean Overman—or at least someone who believes himself to be a Nietzschean Overman. Gerald, himself a “great blonde beast,” is riding the tiger by riding his employees, expressing his “will to power” through mastering the mines. What Gerald doesn’t realize is that, in Nietzschean terms, he is merely, the instrument of will to power, expressing itself in the modern age as industrialism and mechanization. As Colin Milton has discussed at some length, this may actually indicate a confusion, or at least an inconsistency, in Lawrence’s understanding of Nietzsche.

Nietzsche is explicitly invoked in the novel when Ursula identifies Gerald with “Wille zur Macht.” The episode which prompts this comment from her is one of the most famous in the novel. In the chapter “Coal Dust,” Ursula and Gudrun go for a walk, but when they come to the railway crossing have to stop to wait for the colliery train to pass. As they stand there, Gerald Crich trots up riding a “red Arab mare.” The mare is frightened by the locomotive and moves away from it, but Gerald forces her back again and again, cutting into her flesh with his spurs. Ursula is horrified and cries “No—! No—! Let her go! Let her go, you fool, you fool—!” Gudrun, on the other hand, is fascinated by Gerald’s show of brute force over the mare and cries out only as he rides away, “I should think you’re proud.” As we shall see, Gudrun is Gerald’s counterpart, a portrait of the other, purely destructive side of modern will.

The episode with the mare is a good example of Lawrence’s sometimes obvious, but very effective symbolism. The mare represents nature—any and all natural beings—forced into submission before the designs and mechanisms of modernity. There is no other way to bring nature into accord with modern unnaturalism, other than by force and sheer bullying. And so later on Ursula refers to “Gerald Crich with his horse—a lust for bullying—a real Wille zur Macht—so base, so petty.”

In his essay “Blessed are the Powerful” Lawrence remarks, “A will-to-power seems to work out as bullying. And bullying is something despicable and detestable.” In short, in Women in Love Lawrence seems to understand Wille zur Macht as a kind a kind of egoistic self-aggrandizement. In fact, however, what Nietzsche teaches is the surrender to Wille zur Macht, as an impersonal force that expresses itself through us.

Interestingly, perhaps the clearest parallels to Gerald Crich’s philosophy of life, and Lawrence’s treatment of it, are two thinkers Lawrence knew nothing about when he wrote Women in Love: Oswald Spengler and Ernst Jünger, both of whom were strongly influenced by Nietzsche.

Spengler: Faustian Man and Technology

Spengler’s major work Der Untergang des Abendlandes (The Decline of the West) was published in 1918, two years after Lawrence first began working on Women in Love. According to Spengler, “Faustian man” creates a human world of artifacts and schemes not out of any economic motivation but rather out of a sheer desire for mastery.

Spengler’s major work Der Untergang des Abendlandes (The Decline of the West) was published in 1918, two years after Lawrence first began working on Women in Love. According to Spengler, “Faustian man” creates a human world of artifacts and schemes not out of any economic motivation but rather out of a sheer desire for mastery.

However, Spengler believed that in the modern world, at the very height of his technological prowess, Faustian man has begun to decline. In Mensche und Technik (Man and Technics, 1932) Spengler argued that technology had, in effect, taken on a life of its own. In building a technological world, humanity has been caught in the logic and the inevitable course of technology itself.

Technology rapidly becomes indispensable and human beings find themselves unable to do without it. Technological problems inevitably require technological solutions, and the sheer amount of gadgetry that the average human has to be conversant with grows exponentially. Technology comes to dominate the economy, so that most people find themselves not just being served by technology but working most of their lives for its advancement. In short, Faustian man, who had originally created the machines, now comes to be ruled by them.

Gerald certainly presents us with a vivid portrait of Spengler’s Faustian man. Lawrence does not explicitly make anything like Spengler’s argument concerning technology, but something like it lies beneath the surface of Women in Love and some of his other writings. Certainly Lawrence conveys the idea that Gerald foolishly believes himself to be master of the machines. Lawrence writes, “It was this inhuman principle in the mechanism he wanted to construct that inspired Gerald with an almost religious exaltation. He, the man, could interpose a perfect, changeless, godlike medium between himself and the Matter he had to subjugate.”

The medium Lawrence refers to is technology. “And Gerald was the God of the machine, Deus ex Machina.” In Man and Technics, Spengler writes: “To construct a world for himself, himself to be God—that was the Faustian inventor’s dream, from which henceforth arose all projects of the machines, which approached as closely as possible to the unachievable goal of perpetual motion.” Of course, what Gerald doesn’t realize is that he is Spengler’s Faustian man caught in the trap: servant of that which he had created.

Ernst Jünger and the Gestalt of the Worker

Ernst Jünger’s promethean, Nietzschean philosophy of technology comes uncannily close to Gerald’s own ideas. Jünger’s views were forged on the battlefields of World War I, at the very same time Lawrence was writing Women in Love. The war affected both men profoundly, but in profoundly different ways. As I have already mentioned, much of the misanthropy and apocalyptic quality of Women in Love is to be attributed to Lawrence’s horror of the war and what it had reduced men to. Jünger himself regarded the war as horrifying, and his memoir of his days as a soldier, In Stahlgewittern (The Storm of Steel, 1920), is as frightening and chastening an account of war as has ever been written. For Jünger, as for Lawrence (and, later, Heidegger) the war was essentially a technological phenomenon.

However, Jünger came to believe that technology—including the technology of war—was, in effect, a natural phenomenon: the product of some kind of primal, expressive force not unlike Schopenhauer’s Will or Nietzsche’s Will to Power. The very title In Stahlgewittern suggests this understanding of things. Michael E. Zimmerman writes in Heidegger’s Confrontation with Modernity:

On the field of battle, [Jünger] experienced himself at times as a cog in a gigantic technological movement. Yet, unexpectedly, by surrendering himself to this enormous process, he experienced an unparalleled personal elevation and intensity which he regarded as authentic individuation. Generalizing from this experience, he concluded that the best way for humanity to cope with the onslaught of technology was to embrace it wholeheartedly. (Zimmerman, 49)

In Der Arbeiter (The Worker, 1932) Jünger heralded the coming of what Zimmerman calls his “technological Overman.” The productive power underlying all of reality shall body itself forth in the “Gestalt of the worker,” who is essentially a steely-jawed soldier on perpetual march to the technological transformation and mastery of nature. Zimmerman writes how

Jünger asserted that in the nihilistic technological era, the ordinary worker either would learn to participate willingly as a mere cog in the technological order—or would perish. Only the higher types, the heroic worker-soldiers, would be capable of appreciating fully the world-creating, world-destroying technological-industrial firestorm. (Zimmerman, 54–55)

This passage rather uncannily brings to mind Lawrence’s description of the effect that Gerald’s managerial style has on his workers. This is a crucially important passage and I shall quote it at length:

But they submitted to it all. The joy went out of their lives, the hope seemed to perish as they became more and more mechanized. And yet they accepted the new conditions. They even got a further satisfaction out of them. At first they hated Gerald Crich, they swore to do something to him, to murder him. But as time went on, they accepted everything with some fatal satisfaction. Gerald was their high priest, he represented the religion they really felt. His father was forgotten already. There was a new world, a new order, strict, terrible, inhuman, but satisfying in its very destructiveness. The men were satisfied to belong to the great and wonderful machine, even whilst it destroyed them. It was what they wanted. It was the highest that man had produced, the most wonderful and superhuman. They were exalted by belonging to this great and superhuman system which was beyond feeling or reason, something really godlike. Their hearts died within them, but their souls were satisfied.

One can see here that Lawrence seems to accept the Spengler-Jünger thesis that there is an inexorable logic to the modern, technological society and that a fundamental change has come over humanity which makes it possible for men to become servants of the machine. The passage above continues, “It was what they wanted, Otherwise Gerald could never have done what he did.” Lawrence clearly believes that there is something inevitable about what human beings are becoming—but unlike Jünger he cannot embrace it. The Nietzschean-Jüngerian answer to modernity—to ride the tiger—is perhaps the best that one can do to harmonize oneself with the technological world and its apparent dehumanization. But Lawrence absolutely rejects it, and paints Gerald as a tragic, deluded figure. Why? In answering this question, we confront Lawrence’s central objection to modernity.

History: Progressive of Cyclical?

In the deleted “Prologue” to Women In Love (which is interesting for a good many other reasons), Lawrence describes Birkin in the early days of his affair with Hermione as “a youth of twenty-one, holding forth against Nietzsche.” Yet when Lawrence introduces us to Birkin’s own views they seem strikingly Nietzschean. First, however, Lawrence describes how Birkin had studied education (and become a school inspector) under the influence of what seems unmistakably like a warmed-over Hegelianism:

In the deleted “Prologue” to Women In Love (which is interesting for a good many other reasons), Lawrence describes Birkin in the early days of his affair with Hermione as “a youth of twenty-one, holding forth against Nietzsche.” Yet when Lawrence introduces us to Birkin’s own views they seem strikingly Nietzschean. First, however, Lawrence describes how Birkin had studied education (and become a school inspector) under the influence of what seems unmistakably like a warmed-over Hegelianism:

He had made a passionate study of education, only to come, gradually, to the knowledge that education is nothing but the process of building up, gradually, a complete unit of consciousness. And each unit of consciousness is the living unit of that great social, religious, philosophic idea towards which mankind, like an organism seeking its final form, is laboriously growing.

But Birkin quickly becomes disillusioned with this vision, and responds to it in true Nietzschean fashion:

But if there be no great philosophic idea, if, for the time being, mankind, instead of going through a period of growth, is going through a corresponding process of decay and decomposition from some old, fulfilled, obsolete idea, then what is the good of educating? Decay and decomposition will take their own way. It is impossible to educate for this end, impossible to teach the world how to die away from its achieved, nullified form. The autumn must take place in every individual soul, as well as in all the people, all must die, individually and socially. But education is a process of striving to a new, unanimous being, a whole organic form. But when winter has set in, when the frosts are strangling the leaves off the trees and the birds are silent knots of darkness, how can there be a unanimous movement towards a whole summer of fluorescence? There can be none of this, only submission to the death of this nature, in the winter that has come upon mankind, and a cherishing of the unknown that is unknown for many a day yet, buds that may not open till a far off season comes, when the season of death has passed away.

What is Nietzschean here is Birkin’s conviction that he is living at the end of history—but, contra Hegel, it is a time of disintegration and decay. However, unlike Nietzsche and his followers (including Gerald), Lawrence and Birkin do not see any way to transmute this situation into something that becomes life-advancing. What Gerald cannot see, but Birkin and Lawrence clearly can, is that the submission of the miners to “the Gestalt of the worker” represents the first stage in the complete breakdown of the Western world. The same passage quoted earlier from “The Industrial Magnate” chapter continues:

[Gerald] was just ahead of [his workers] in giving them what they wanted, this participation in a great and perfect system that subjected life to pure mathematical principles. This was a sort of freedom, the sort they really wanted. It was the first great step in undoing, the first great phase of chaos, the substitution of the mechanical principle for the organic, the destruction of the organic purpose, the organic unity, and the subordination of every organic unit to the great mechanical purpose. It was pure organic disintegration and pure mechanical organisation. This is the first and finest state of chaos.

Submission to or mastery of the modern, technological world—whether that world represents an advance or a degeneration—is not the answer for Lawrence because he believes that true human fulfillment lies in submission to something higher, or perhaps deeper: the true unconscious. Gerald offers his miners a kind of “freedom,” but it is the illusory freedom of the mind and ego from the call of the natural self.

Essentially, for Lawrence, the modern world is characterized by the subordination of the organic to the mechanical; of the natural to the planned, automated, and “rational.” But in severing the tie to the organic and placing themselves in the service of the machine and the idea, human beings lose their fundamental being, and their sense of having a place in the cosmos.

The real problem with Nietzsche is that although he talks a great deal about the body and about “instincts,” everything for him is still, to borrow Lawrence’s language, “in the head.” In his Genealogy of Morals, Nietzsche presents us with an attractive discussion of the healthy, “natural” morality of the master type, which values such things as health, strength, and beauty.

But Nietzsche’s own approach to morals amounts to a conscious and willful desire to relativize all values—to declare that there is no natural source, and no natural values. The Overman, in fact, gets to simply posit new values. This appears to be a purely intellectual, and largely arbitrary affair. The idea of “creating” values is psychologically implausible: how can anyone believe in, let alone fight for, values and ideals that they have consciously dreamed up?

The Impotent Übermensch

In his characterization of Gerald Crich, Lawrence gives us a realistic portrait of what would become of an “Overman” in real life. Keep in mind that it is Lawrence’s belief that when we abstract ourselves from the natural world, and from the promptings of the nature within us, we suffer and even, in a way, go mad. This is, in effect, what becomes of Gerald. In the concluding passages of the “Industrial Magnate” chapter Lawrence describes the psychological toll that mastery of Matter has taken on Gerald:

And once or twice lately, when he was alone in the evening and had nothing to do, he had suddenly stood up in terror, not knowing what he was. And he went to the mirror and looked long and closely at his own face, at his own eyes, seeking for something. He was afraid, in mortal dry fear, but he knew not what of. He looked at his own face. . . . He dared not touch it, for fear it should prove to be only a composition mask.

Inevitably, Gerald’s sense of dissociation displays itself in a sexual manner:

He had found his most satisfactory relief in women. . . . The devil of it was, it was so hard to keep up his interest in women nowadays. He didn’t care about them anymore. . . . No, women, in that sense, were useless to him any more. He felt that his mind needed acute stimulation, before he could be physically roused.

The clear suggestion is that Gerald is practically impotent. Like Clifford in Lady Chatterley’s Lover, whose impotence has a purely physical cause, Gerald is physically numb; he lives from the mind alone. Disconnected from his natural being, he no longer feels spontaneous, animal arousal for the opposite sex. He has become “re-wired,” so to speak, so that the route to the sexual center, in his case, is by way of the intellect; he can only become sexually aroused through his mind.

The irony here is that Gerald is portrayed throughout the novel as handsome, strong, and virile in both a physical and spiritual sense: he is a master of matter, and of women. In fact, however, both his physical and spiritual virility is mere appearance. He is master neither of himself nor of his world. Nor is he even master of his erection. On the other hand, Birkin, who is portrayed as physically weaker, is at least truly virile in a spiritual sense. This is the reason he manages to avoid becoming “absorbed” by Ursula.

Lawrence is famous for characterizing relations between the sexes as a battle, or, more accurately, a struggle unto death. In Women in Love, the two couples battle each other continuously, but most of the fighting is done by the women against the men. (The famous nude wrestling match between Gerald and Birkin is a purely honest, physical contest, whose only psychological undertones are homoerotic.)

Lawrence is famous for characterizing relations between the sexes as a battle, or, more accurately, a struggle unto death. In Women in Love, the two couples battle each other continuously, but most of the fighting is done by the women against the men. (The famous nude wrestling match between Gerald and Birkin is a purely honest, physical contest, whose only psychological undertones are homoerotic.)

Birkin compromises with Ursula in settling for love rather than something “higher.” But despite this he maintains his integrity and individuality. It is a difficult feat, and even at the novel’s end we see Ursula working to try and undermine his desire for another kind of love in his life: “Aren’t I enough for you?” she asks him.

Gerald, however, cannot pull it off. He lacks Birkin’s spiritual virility: his ability to maintain himself, inviolate, even in giving himself to a woman. Gurdrun’s onslaughts are much more destructive and insidious than Ursula’s, and in the end the “manly” Gerald is broken by them.

Gudrun Brangwen, the Modern Woman

Gerald Crich is only one half of Lawrence’s portrait of the “modern individual.” The other half is Gudrun Brangwen. Of course, Birkin and Ursula are modern individuals, though in a different sense. The latter couple are both seeking some fulfilling way to live in, or in spite of, the modern world. They (especially Birkin) have achieved some critical distance from it.

Gerald and Gudrun, however, are both creatures of modernity. Gerald has consciously embraced the modern rootless prometheanism; Gudrun unconsciously. Further, Gudrun is not simply a female version of Gerald. Her “modernity” consists in certain traits which complement those of Gerald. What complicates matters is that Ursula and Gudrun also represent, for Lawrence, the two halves of femininity, and not just modern femininity.

In the first chapter of the novel, Gudrun reacts with revulsion to one of the locals as she and Ursula walk through Beldover: “A sudden fierce anger swept over the girl, violent and murderous. She would have liked them all annihilated, cleared away, so that the world was left clear for her.” It is interesting to compare this with Birkin’s (and Lawrence’s) fantasies of annihilation. Birkin, the complete misanthrope, wants to wipe the earth clean of humanity, including himself, so that there is only “uninterrupted grass, and a hare sitting up.” In Gudrun’s fantasy, she is left sitting up and everyone else is wiped away.

This small detail gives us an important clue to Gudrun’s character, which is fundamentally egoistic. A thoroughgoing egoism is always nihilistic, for it wills that all limitation or opposition to the ego be cancelled. But even the mere existence of other human beings (or anything else, for that matter) constitutes a limitation on the ego.

Just as Lawrence does with Gerald, this “self-assertion” on Gudrun’s part is connected, by allusion, with Nietzsche. This time, however, the allusion is put into the mouth of the character herself in what seems on the surface like a purely innocent remark. Enjoying the snowy Tyrol, Gudrun exclaims, “Isn’t the snow wonderful! Do you notice how it exalts everything? It is simply marvellous. One really does feel übermenschlich—more than human.”

Like Gerald, Gudrun lives in a state of abstraction from the body and from nature. In sex she remains perfectly detached. Writing of the aftermath of Gudrun’s first sexual encounter with Gerald, Lawrence emphasizes again and again her full consciousness, while Gerald lays on top of her, asleep and satiated. He tells us “she lay fully conscious.” And: “Gudrun lay wide awake, destroyed into perfect consciousness.” And: “She was suspended in perfect consciousness—and of what was she conscious?” (He does not truly answer the question.)

Gudrun is revolted by the rhythms of nature and by natural objects—even though, ironically, it is small animals that she depicts in her sculpture (perhaps this is the only way she can encounter them, as things she molds and creates herself). Holding Winifred Crich’s pet rabbit Bismarck, who puts up quite a struggle, “Gudrun stood for a moment astounded by the thunderstorm that had sprung into being in her grip. Then her colour came up, a heavy rage came over her like a cloud. . . . Her heart was arrested with fury at the mindlessness and bestial stupidity of this struggle, her wrists were badly scored by the claws of the beast, a heavy cruelty welled up in her.”

The mechanical succession of day after day revolts her. Very early in the novel she confesses to Ursula, “I get no feeling whatever from the thought of bearing children.” She looks at Ursula, who is clearly flustered by this, with a “mask-like expressionless face.” When Ursula, intimidated by her sister, stammers out a reply, “A hardness came over Gudrun’s face. She did not want to be too definite.” This desire to remain indefinite is essential to Gudrun’s character.

In fact, the essence of Gudrun is nothingness. In the first chapter, Lawrence tells us “there was a terrible void, a lack, a deficiency of being within her.” In conversation with Gerald, Birkin describes her as a “restless bird,” and says that “She drops her art if anything else catches her. Her contrariness prevents her from taking it seriously—she must never be too serious, she feels she might give herself away. And she won’t give herself away—she’s always on the defensive. That’s what I can’t stand about her type.” Gudrun’s “type” is the modern individual who cannot stand to be tied to anything, who is in constant flux, wary of anything that would compel her to make a commitment, whether to a relationship or a career, or whatever. Plato in the Republic essentially winds up describing this modern type when he attempts to characterize the sort of character produced by a democracy:

“Then,” [said Socrates], “he also lives along day by day, gratifying the desire that occurs to him, at one time drinking and listening to the flute, at another downing water and reducing; now practicing gymnastic, and again idling and neglecting everything; and sometimes spending his time as though he were occupied with philosophy. Often he engages in politics and, jumping up, says and does whatever chances to come to him; and if he ever admires any soldiers, he turns in that direction; and if it’s money-makers, in that one. And there is neither order nor necessity in his life, but calling this life sweet, free, and blessed, he follows it throughout.”

“You have,” [said Adeimantus], “described exactly the life of a man attached to the law of equality.”

Near the end of the novel, Lawrence tells us of Gudrun:

Her tomorrow was perfectly vague before her. This was what gave her pleasure. . . . Anything might come to pass on the morrow. And to-day was the white, snowy iridescent threshold of all possibility. All possibility—that was the charm to her, the lovely, iridescent, indefinite charm—pure illusion. All possibility—because death was inevitable, and nothing was possible but death.

She did not want things to materialize, to take any definite shape. She wanted, suddenly, at one moment of the journey tomorrow, to be wafted into an utterly new course, by some utterly unforeseen event, or motion.

When Gudrun is asked the question wohin? (where to?) Lawrence tells us that “She never wanted it answered.”

When Gudrun is asked the question wohin? (where to?) Lawrence tells us that “She never wanted it answered.”

The quintessential modern individual does not, in fact, want to be anything at all, for to be something definite would close off other possibilities. And so the modern individual is always oriented toward the future, which contains all possibilities, rather than toward the present. In this respect, Gudrun’s character perfectly complements Gerald’s. Gerald has completely abstracted himself from the present by regarding everything else as “Matter” to be transformed according to his will.

This is, again, what Heidegger tells us is the modern perspective on nature. Because everything is merely raw material to be made over into something else, nothing is ever regarded as possessing a fixed identity. The essence of everything, really, is to become something else, something better. The being of things is thus something projected into the future; something that will be revealed at a later date, through human ingenuity. The result of this treatment of things as raw material is that it produces individuals who live for the future: for what will be, and for what they will be. This is how “abstraction” from the present occurs. A key ingredient in this, of course, is a kind of radical subjectivism and anthropocentrism: the being of things is something that will be created by human beings.

The modern world is therefore a world of individuals who are, mentally, quite literally elsewhere. On the one hand they are disconnected from the nature world (which to them is essentially “stuff”) and from their own nature, which they erroneously believe is something they can decide on or even re-make. They are disconnected, in fact, from presentness in general.

At one point Lawrence reveals to us that Gudrun suffers from the nagging feeling that she is merely an “onlooker” in life whereas her sister is a “partaker.” Indeed she is an onlooker and this is the key to her weird “consciousness” in the sex act. Gerald is an onlooker too, hence the sense of unreality he experiences when looking at himself in the mirror. They are both creatures of the mind, of idealism, and of futurity.

And this is truly the heart of Lawrence’s critique of modernity: that we have lost touch with the sense of being a part of nature, and of being in our bodies, in present time. The ultimate result of such abstraction from nature, the body, and the present is the destruction of nature, of any possibility of inner peace and fulfillment, and of community.

Both Gerald and Gudrun are fundamentally destructive, nihilating individuals, but of the two Gudrun represents destruction in its purest form. Gerald destroys in order to transform and, as we saw earlier, he believes himself to be an agent of history and of social reform. (Or, at least, this is the moral veneer he paints over his activities.) With Gudrun, there is not such self-justification. Of course, ultimately Gerald’s transformation of Matter is perfectly destructive, and so one can plausibly claim that in a sense Gudrun is the more honest of the two, though she is not self-aware in her destructiveness.

Gudrun represents the inner truth of Gerald’s prometheanism laid bare. This point is conveyed through the structure of Lawrence’s novel itself. Gudrun is a presence throughout the entire book, but by the last few chapters the story becomes focused very much on her. And it is in the last few chapters that the pure nihilism of her character is brought to the fore. At the same time, Gerald, who had earlier been a relatively strong figure, is reduced to inefficacy and becomes almost a shadowy presence. His physical death comes, in way, as merely an outward expression of an internal death that had already taken place in his soul.

Gudrun and Loerke

What seems to immediately precipitate Gerald’s suicide is that Gudrun gives every indication of leaving him for an artist named Loerke who she has met in the Tyrol. Loerke, better than Gerald, personifies Jünger’s promethean modernism. Loerke is a sculptor who shares with Gudrun and Ursula his plans for a granite frieze for a huge factory in Cologne. Churches, he tells the two sisters are “museum stuff,” and since the world is now dominated by industry, not religion, art should come together with industry to make the modern factory into a new Parthenon:

“And do you think then,” said Gudrun, “that art should serve industry?”

“Art should interpret industry as art once interpreted religion,” he said. . . .

“But is there nothing but work—mechanical work?” said Gudrun.

“Nothing but work!” he repeated, leaning forward, his eyes two darknesses, with needle-points of light. “No, it is nothing but this, serving a machine, or enjoying the motion of a machine—motion, that is all. . . .”

Loerke exhibits the same destructive, modern will we find in Gerald and Gudrun, but come to full consciousness of itself. This is what attracts Gudrun to Loerke. She has realized that Gerald is weak—he possesses the destructive will, but cannot own up to it; he must hide it under his idealism. Loerke has embraced the Will to Power without illusion:

To Gudrun, there was in Loerke the rock bottom of all life. Everybody else had their illusion, must have their illusion, their before and after. But he, with a perfect stoicism, did without any before and after, dispensed with all illusion. He did not deceive himself in the last issue. In the last issue he cared about nothing, he was troubled about nothing, he made not the slightest attempt to be at one with anything. He existed a pure, unconnected will, stoical and momentaneous. There was only his work.

Birkin describes him a bit later as “a gnawing little negation, gnawing at the roots of life.” Loerke is completely detached from nature and from the body. His sexuality is indeterminate. Though he has a male lover, he is drawn to Ursula. But he tells her that it wouldn’t matter to him if she were one hundred years old: all that matters is her mind.

The Gudrun-Gerald relationship plays itself out, and reaches its tragic end, in the Alps. The choice of locations is significant. Attentive readers of Lawrence’s fiction will note that he tends to depict his characters as either “watery” or “fiery.” In Women in Love Birkin and Ursula are the fiery pair, contrasted to Gudrun and Gerald, who are watery. Gerald meets his end in the novel when he commits suicide by wandering off into the snow and freezing to death. For Lawrence, this act represents Gerald quite literally “returning to his element.” Though Gudrun and Ursula are bound together by blood, the deeper bond is between Gudrun and Gerald, and it is metaphysical. They are the two aspects of the modern soul: one productive without a purpose; the other destructive, nihilating.

Ursula’s Primacy

In a sense it is strange to argue as I did earlier that Women in Love represents the continuation of Ursula’s story. For one thing, the novel seems to focus more directly on the Birkin-Gerald relationship. Further, Gudrun is actually a more vivid character than Ursula. Nevertheless, I would still argue that Ursula is the central character. She is the most “natural” of any major character in the novel; the least in conflict with herself.

We are made to feel closer to Birkin, as he is transparently Lawrence’s self-portrait. But Birkin is “abstracted” from life in his own way. He berates Hermione for having everything in her head and lacking real sensuosity. Yet so much of Birkin is theory and talk. He wants some kind of total, transformative experience that would give him a real sense of being alive—yet he wants to hold onto his ego boundaries. He wants love, but then again he doesn’t. He wants to give himself to Ursula, but not totally. Admirers of Lawrence the man often miss the rather obvious flaws in Birkin’s character, and are thus oblivious to how Lawrence may have achieved a critical distance from Birkin (and from himself).

In the end, Birkin’s “problems” are in large measure solved by the oldest means in the world: the force of natural love, and the institution of marriage. Up to a point (but only up to a point) Birkin simply surrenders his abstract ideas about relationships—about finding something “more” than love—and surrenders to Ursula. Ursula knows from deep within herself, the falsity of Birkin’s ideals. Through her he comes to know what Lawrence would call “the sweetness of accomplished marriage.” There is only one part of him that remains unfulfilled. But that is a subject for another essay . . .

I have contributed several essays to Counter-Currents dealing with D. H. Lawrence’s critique of modernity. Those essays might lead the reader to believe that Lawrence treats modernity as a universal ideology or worldview that could be found anywhere.

I have contributed several essays to Counter-Currents dealing with D. H. Lawrence’s critique of modernity. Those essays might lead the reader to believe that Lawrence treats modernity as a universal ideology or worldview that could be found anywhere. It is Lawrence’s analysis of Melville’s Moby Dick, however, that is perhaps his most incisive. He sees in this simple story an encapsulation of the American spirit, the American thanatos itself. Here is Lawrence summing up his interpretation:

It is Lawrence’s analysis of Melville’s Moby Dick, however, that is perhaps his most incisive. He sees in this simple story an encapsulation of the American spirit, the American thanatos itself. Here is Lawrence summing up his interpretation:

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

D. H. Lawrence’s greatest novel is also his most anti-modern. Written between April and October of 1916 in Cornwall, during some of the darkest days of the First World War,

D. H. Lawrence’s greatest novel is also his most anti-modern. Written between April and October of 1916 in Cornwall, during some of the darkest days of the First World War,  But why did Jane Austen’s England have the power to be something else? And what else did it have the power to be? For the answers to these questions we must, in essence, look back to The Rainbow. Jane Austen’s England still preserved some connection to the land—a sense of belonging to nature. What England then had the “power to be” was nothing grand and idealistic: it had the power simply to be its natural self. The people of Jane Austen’s England made and enjoyed beautiful objects—but these objects were an ornament to a life lived in relative closeness to the earth.

But why did Jane Austen’s England have the power to be something else? And what else did it have the power to be? For the answers to these questions we must, in essence, look back to The Rainbow. Jane Austen’s England still preserved some connection to the land—a sense of belonging to nature. What England then had the “power to be” was nothing grand and idealistic: it had the power simply to be its natural self. The people of Jane Austen’s England made and enjoyed beautiful objects—but these objects were an ornament to a life lived in relative closeness to the earth. For Nietzsche, on the other hand, the end of history meant the death of everything that ennobles the human race. Without anything to struggle over or to believe in so strongly that one would be willing to fight and die for it, humanity would sink to the level of what Nietzsche called the Last Man, Homo economicus: the man whose aspirations do not rise above material comfort, safety, and security. The only hope was the arrival of the Overman, who would create new values, new systems of belief, and initiate new conflicts among human beings. In short, the Overman would re-start history. Nietzsche’s writings, in their trenchant critique of all Western beliefs and values, can be seen as an attempt to actually hasten the collapse of the modern world and usher in the Overman.

For Nietzsche, on the other hand, the end of history meant the death of everything that ennobles the human race. Without anything to struggle over or to believe in so strongly that one would be willing to fight and die for it, humanity would sink to the level of what Nietzsche called the Last Man, Homo economicus: the man whose aspirations do not rise above material comfort, safety, and security. The only hope was the arrival of the Overman, who would create new values, new systems of belief, and initiate new conflicts among human beings. In short, the Overman would re-start history. Nietzsche’s writings, in their trenchant critique of all Western beliefs and values, can be seen as an attempt to actually hasten the collapse of the modern world and usher in the Overman. Spengler’s major work Der Untergang des Abendlandes (The Decline of the West) was published in 1918, two years after Lawrence first began working on Women in Love. According to Spengler, “Faustian man” creates a human world of artifacts and schemes not out of any economic motivation but rather out of a sheer desire for mastery.

Spengler’s major work Der Untergang des Abendlandes (The Decline of the West) was published in 1918, two years after Lawrence first began working on Women in Love. According to Spengler, “Faustian man” creates a human world of artifacts and schemes not out of any economic motivation but rather out of a sheer desire for mastery. In the deleted “Prologue” to Women In Love (which is interesting for a good many other reasons), Lawrence describes Birkin in the early days of his affair with Hermione as “a youth of twenty-one, holding forth against Nietzsche.” Yet when Lawrence introduces us to Birkin’s own views they seem strikingly Nietzschean. First, however, Lawrence describes how Birkin had studied education (and become a school inspector) under the influence of what seems unmistakably like a warmed-over Hegelianism:

In the deleted “Prologue” to Women In Love (which is interesting for a good many other reasons), Lawrence describes Birkin in the early days of his affair with Hermione as “a youth of twenty-one, holding forth against Nietzsche.” Yet when Lawrence introduces us to Birkin’s own views they seem strikingly Nietzschean. First, however, Lawrence describes how Birkin had studied education (and become a school inspector) under the influence of what seems unmistakably like a warmed-over Hegelianism: Lawrence is famous for characterizing relations between the sexes as a battle, or, more accurately, a struggle unto death. In Women in Love, the two couples battle each other continuously, but most of the fighting is done by the women against the men. (The famous nude wrestling match between Gerald and Birkin is a purely honest, physical contest, whose only psychological undertones are homoerotic.)

Lawrence is famous for characterizing relations between the sexes as a battle, or, more accurately, a struggle unto death. In Women in Love, the two couples battle each other continuously, but most of the fighting is done by the women against the men. (The famous nude wrestling match between Gerald and Birkin is a purely honest, physical contest, whose only psychological undertones are homoerotic.) When Gudrun is asked the question wohin? (where to?) Lawrence tells us that “She never wanted it answered.”

When Gudrun is asked the question wohin? (where to?) Lawrence tells us that “She never wanted it answered.”

Par Robert Spieler

Par Robert Spieler