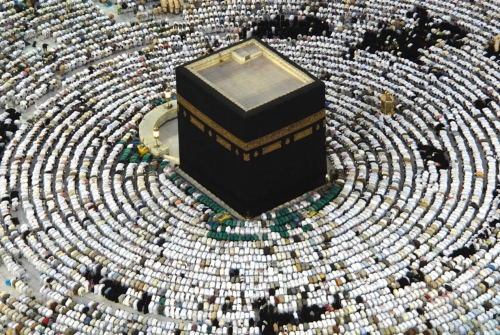

Sin lugar a dudas, a primera vista, el ojo inexperto sería incapaz de distinguir a una persona aleví del resto de musulmanes. Incluso sus centros de culto, decorados en ocasiones con cúpulas y minaretes, podrían pasar, vistos desde el exterior, como una mezquita más. No obstante, a medida que se curiosea con mayor detalle, se dará cuenta de las enormes diferencias existentes entre la comunidad alevi y los suníes y shiíes. Pero, ¿quiénes son los alevíes?

Sin lugar a dudas, a primera vista, el ojo inexperto sería incapaz de distinguir a una persona aleví del resto de musulmanes. Incluso sus centros de culto, decorados en ocasiones con cúpulas y minaretes, podrían pasar, vistos desde el exterior, como una mezquita más. No obstante, a medida que se curiosea con mayor detalle, se dará cuenta de las enormes diferencias existentes entre la comunidad alevi y los suníes y shiíes. Pero, ¿quiénes son los alevíes?

Una fe nacida en las montañas

Los alevíes son fieles pertenencientes a una de las ramas no ortodoxas del Islam. Su tradición bebe de las enseñanzas del místico Hacı Bektaş, que vivió en la península de Anatolia entre 1209 y 1271 d.C. Su filosofía se basaba en el respeto hacia el resto de seres humanos y en la modestia y la equidad como formas de demostrar el amor por Dios y purificar la propia alma. No obstante, lo cierto es que no era teólogo ni llevó a cabo estudios en ninguna madrasa –escuela coránica–, sino que sus conocimientos los adquirió en sus viajes, por sus contactos con diferentes cofradías sufíes y por herencia de las tradiciones de tipo chamánico de su propia tribu, de origen turconamo. De hecho, siempre se mantuvo más cerca de la gente común que de los doctores de la ley islámica.

A Bektaş se le atribuirían poderes de inspiración divina, tales como la adivinación o la sanación, lo que poco a poco iría congregando una cofradía a su alrededor. Así se configuraría un culto que mezclaba ritos islámicos con prácticas chamánicas procedentes de Asia central, a lo que se añadían prolongados períodos de meditación y el uso de sustancias alucinógenas como forma de liberar al espíritu del cuerpo y acercarse a Dios. Todo ello características comunes entre las ramas gnósticas de la religión de Mahoma, presentes en todo el mundo islámico.

De las tribus turcomanas que seguirían las enseñanzas de Bektaş surgiría la comunidad aleví, la cual se impregnaría, de una forma u otra, de influencias de otros cultos y sectas que arraigarían en la dinámica península de Anatolia. Allí confluirían el shiismo en sus diversas corrientes y el sunismo, además de prácticas ancestrales de origen tribal y procedentes de toda Asia, traídas por las tribus nómadas en sus desplazamientos por el continente. Entre estas influencias se encontraría la de los Ahi, una cofradía religiosa-gremial, creada por el gran maestro Ahi Evren Veli, que bebía de la tradición de la futuwwa, la caballería islámica. Y también los hurufíes, una doctrina islámica cabalística con claras influencias shiíes y con elementos preislámicos.

Posteriormente, diversos acontecimientos reforzarían la autoconciencia de los alevíes como una secta particular. En primer lugar las matanzas de shiíes que el Sultán Selim I el Severo llevó a cabo en la Anatolia ante la amenaza de los persas safávidas –los cuales harían del shiísmo la religión oficial de Irán– y que afectarían a las comunidades alevíes por sus semejanzas doctrinales con esa rama del islam. En segundo término, también en este período, los dirigentes otomanos reforzarían el sunismo y su ortodoxia, hasta ese momento algo ambigua. Todo ello obligaría a los alevíes a huir y esconderse en las zonas montañosas. Allí, separados del resto de la comunidad musulmana, a salvo de la represión imperial y sin influencias de otros cultos, desarrollarían su fe y consolidarían la doctrina aleví. No obstante, es notable comprobar que no se les llamaría como tal hasta el siglo XIX, siendo hasta entonces considerados herejes, blasfemos o, simplemente, ateos.

Un culto particular

En definitiva, en la forja de Anatolia se configuraría una fe muy especial, que si bien compartiría infinidad de creencias, símbolos y prácticas con alguna de las ramas del Islam, diferiría en muchas otras. Así pues, los alevíes creen –de manera similar al Islam shií– en la trinidad formada por Dios, Mahoma y Alí –yerno del profeta–, además de divinizar a diversos personajes, como el propio Hacı Bektaş o el Shah Ismail. Por otra parte, algo curioso de los alevíes es que no creen en la muerte como un hecho definitivo, ni en Dios como un juez que condena al cielo o al infierno en función de los actos en el mundo terrenal, sino en la reencarnación del alma en otro cuerpo tras el fin de cada vida, y en la unidad del mundo con la divinidad. En función de ello consideran a sus grandes héroes y heroínas como reencarnaciones del propio Alí. Asimismo, y aunque como el resto de musulmanes también consideran sagrados la Biblia o la Torá, no usan el mismo Corán que los musulmanes suníes, sino el Corán que supuestamente fue memorizado por Alí.

Por otro lado, no practican rituales fundamentales del Islam suní, tales como el ramadán o las cinco oraciones diarias, sino que tienen su propio ayuno, los doce primeros días del mes de muharram –el primer mes del calendario musulmán–, y además practican ayunos para purificarse cuando sufren alguna dolencia física o espiritual. De la misma forma, el ritual de la oración aleví es distinto, cumpliendo la función tanto de ceremonia religiosa como de reunión social, y llevándose a cabo en medio de bailes y al son de la música. Todo ello configurando un rito cuya función es tanto la de unirse con Dios como la de purificarse del mundo material.

Además, algo muy característico de los alevíes, que remarcaría sus enormes diferencias con el resto de musulmanes, es la concepción igualitaria entre hombres y mujeres dentro del espacio para el culto. Y es que, a diferencia de los que ocurre en las mezquitas suníes o shiíes, no existen espacios separados para cada género en el ineterior de los templos, y tanto mujeres como varones pueden encargarse de dirigir la oración de la comunidad.

Los otros hijos de Atatürk

En 1919, tras la Primera Guerra Mundial, lo que quedaba del mesmembrado Imperio Otomano, y que constituiría el territorio de la futura República de Turquía, quedaría dividida y ocupada por las potencias vencedoras de la contienda. No obstante, esta situación no iba a durar mucho, pues la resistencia nacionalista, dirigida por Mustafa Kemal Atatürk –padre de los turcos–, se reagruparía en el noroeste, iniciando la guerra de independencia. Los alevíes también se unirían a la guerra, atraídos por los valores que promulgaba el líder turco, tales como el laicismo, el republicanismo o la igualdad de género, el cual además rendiría respetos a su querido santo Hacı Bektaş.

Los turcos saldrían victoriosos del enfrentamiento contra los invasores y en 1923 se proclamaría la República. No obstante, y si bien el Estado turco se construiría impulsado por un nacionalismo de tipo secular, en el cual política y religión debían estar separados en dos ámbitos diferenciados, en la práctica no todas las religionas vendrían a gozar del mismo respeto. El objetivo de Mustafa Kemal no sería tanto el erradicar la religión, consciente de la importancia que tenía ésta para muchos de los habitantes del Estado que pretendía diseñar, construir y gobernar, sino someterla al control burocrático del aparato estatal, adecuándola así a su propósito de configurar una conciencia nacional desde cero. Las instituciones creadas para ello fueron el Directorio de Asuntos Religiosos y el Directorio de Fundaciones Religiosas. No obstante, estas instituciones no representarían la pluralidad religiosa de la nueva república, sino que impondrían el Islam suní mayoritario como la versión verdadera de la fe. Con ello, las comunidades no suníes, entre ellas los alevíes, quedarían totalmente excluidas, los cuales, a pesar de conformar alrededor de un 20% de la población hasta nuestros días, serían obligados a reprimir su identidad cultural, haciéndose pasar por suníes si querían ser tratados como miembros iguales de la nación turca en la esfera pública.

A partir de ese momento los alevíes, que se habían visto sometidos a diversos tipos de persecución, comenzarían a experimentar discriminación a muchos niveles. Por ejemplo, sería muy difícil encontrar alevíes en puestos prominentes de la burocracia o el ejército. Y, por supuesto, la educación religiosa que se llevase a cabo en los colegios sería exclusivamente suní. Además, los clérigos suníes y sus mezquitas recibirían sueldos y financiación estatal, un privilegio del que jamás gozarían las comunidades alevíes, cuyos centros de culto, las llamadas cemevis, ni siquiera serían considerados como tal.

Posteriormente, durante las primeras décadas de la república, se producirían una serie de levantamientos protagonizados por el pueblo kurdo, que reclamaba para sí la autodeterminación y la formación de un Estado propio, algo que los tratados internacionales del fin de la guerra les habían negado. Muchos kurdos-alevíes participarían en dichas revueltas –las cuales serían brutalmente aplastadas–, lo que llevaría a que a lo largo de las sucesivas décadas el discurso hegemónico kemalista equiparara a los alevíes con los kurdos, justificando así ataques contra los primeros. Si tenemos en cuenta la articulación del nacionalismo kemalista alrededor de una fuerte identidad étnica turca, que considera a los kurdos como un pueblo atrasado y oscurantista o, en el mejor de los casos, como turcos que han olvidado su turquicidad y que hay que reeducar, podemos entender el estigma con el que los alevíes fueron marcados.

A pesar de todo, lo cierto es que los alevíes fueron de los grupos más receptivos a la hora de aceptar la nueva coyuntura, viendo el proceso de secularización impulsado por el Estado como un avance, y no cuestionaron su posición dentro del orden político hasta décadas recientes. De hecho, con la llegada del sistema pluripartidista en los años 40 muchos alevíes votarían al Partido Democrático (DP), heredero de la tradición republicana. Asimismo, aún a día de hoy continúan siendo uno de los apoyos sociales más amplios de los partidos políticos kemalistas.

Cuando las calles se tiñeron de rojo

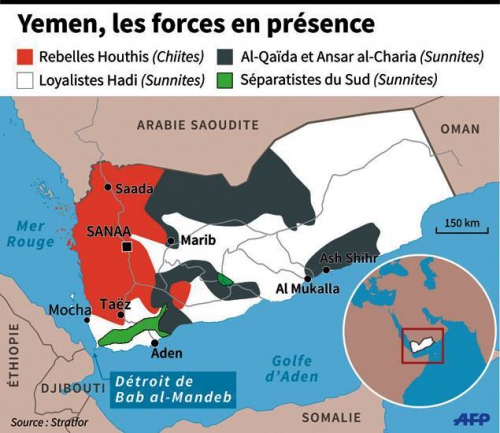

Más adelante, el aumento de las libertades propiciado por la constitución de 1961 llevaría al desarrollo de organizaciones alevíes, impulsadas además por unas élites intelectuales que comenzarían a fomentar el desarrollo de una identidad particular. No obstante, sería en los 70 cuando la polarización política turca alcanzara su punto culmimante, la época en que los alevíes adquirirían un mayor y más determinante peso político. Durante este tiempo, los partidos conservadores turcos se inclinarían cada vez más hacia la derecha, identificándose política e ideológicamente con el espectro reiligioso suní. A su vez, los partidos de izquierdas de inspiración marxista también se radicalizarían, atrayéndose hacia sí a los grupos nacionalistas kurdos, y también a los alevíes. Serían los particulares años de plomo para Turquía, que vio como las guerrillas de uno y otro bando tomaban las calles, con el ejército y las fuerzas de seguridad del estado participando activamente en las batallas urbanas, apoyando a los grupos de extrema derecha, y con más de 20 asesinatos al día durante la mayor parte de la década.

Todo ello vendría a ligar irremediablemente a la comunidad aleví con el eje político de la izquierda radical, siendo considerados un grupo subversivo; además se reforzaría su equiparación con el pueblo kurdo, que además en las décadas siguientes vendría a adquirir la connotación de terrorista. Esto tendría una enorme importancia especialmente a partir del golpe de estado de 1980, cuando la represión estatal hacia los movimientos de izquierda, de los kurdos y de cualquier tipo de oposición política se dispararía. Pero de hecho, incluso antes, durante los propios años 70, los grupos de extrema derecha llevarían a cabo progroms contra comunidades alevíes, como es el caso de la masacre ocurrida en 1978 en la ciudad de Kahramanmaraş, perpetrada por los Lobos Grises y que acabaría con la vida de más de cien personas. Este tipo de sucesos se repetirían en las décadas siguientes, como en la masacre de Sivas de 1993, esta vez a manos de un grupo de radicales salafistas.

La síntesis turco-islámica

En definitiva, de nuevo los alevíes se verían definidos por el discurso dominante de las instituciones del Estado como una amenza para la estabilidad de la nación. Un hecho que se uniría a la potenciación por parte de los militares de la síntesis turco-islámica a partir del golpe de Estado de 1980, que pretendía movilizar la religión para combatir la movilización política antiestatal, y que desarrollaría una conciencia nacional turca reforzada con una buena dosis de conservadurismo religiosos de tipo suní, que volvería a situar a la comunidad aleví ante una encrucijada: asimilar el Islam suní mayoritario como propio o verse abocados a la marginación. Los alevíes volvían así a la casilla de salida de los primeros días de la república con Mustafa Kemal.

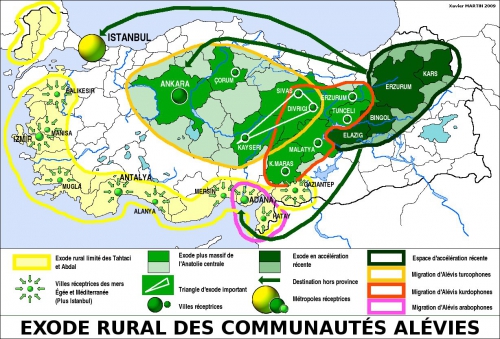

No obstante, a su vez sería el proceso de neoliberalización económica iniciado en los 80 el que pondría en cuestión el modelo estatocéntrico de modernización, impulsando las posturas que favorecían a los individuos frente al Estado. Una situación fomentada también por las cada vez más estrechas relaciones con la Unión Europea (UE) y la Organización para la Seguridad y la Cooperación Europea (OSCE) en las sucesivas décadas, que pedirían a Turquía aplicar de manera progresiva una serie de criterios fundamentales en materia de derechos humanos. En este contexto, los alevíes, los cuales se sumarían también al éxodo rural hacia los grandes núcleos urbanos turcos, donde les sería complicado seguir con sus rituales tradicionales, empezarían a reclamar con mucha más fuerza su reconocimiento oficial como un colectivo diferenciado de la mayoría suní, lo que llevaría asociado la demanda de una serie de derechos políticos y sociales determinados.

Los alevíes y el nuevo sultán

Posteriormente, tras la década de 1990, los movimientos islamistas articularían una identidad nacional alternativa que definiría la nación como una civilización otomana esencialmente islámica, en contraste con la identidad oficial, laica y occidentalizada. De esta nueva concepción de la república turca nacería, en agosto de 2001, el Partido de la Justicia y el Desarrollo (AKP por sus siglas en turco), liderado por el actual presidente, Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Quince meses después se celebrarían las elecciones, iniciándose una nueva era para la política de la república. Y es que cuando en 2002 el partido AKP se alzara victorioso en las elecciones, se iniciaría un proceso que cambiaría la política turca hasta la actualidad. Por un lado, el poder que los militares habían ostentado hasta el momento sería puesto bajo control de una forma que no había ocurrido en los casi 70 años de la república turca. Por otro, la cuestión kurda se pondría sobre la mesa con el diálogo de por medio, un cambio fundamental tras una guerra de casi 20 años que se había cobrado decenas de miles de vidas. En definitiva, los discursos frente a temas fundamentales en la historia política turca cambiarían radicalmente.

Posteriormente, tras la década de 1990, los movimientos islamistas articularían una identidad nacional alternativa que definiría la nación como una civilización otomana esencialmente islámica, en contraste con la identidad oficial, laica y occidentalizada. De esta nueva concepción de la república turca nacería, en agosto de 2001, el Partido de la Justicia y el Desarrollo (AKP por sus siglas en turco), liderado por el actual presidente, Recep Tayyip Erdogan. Quince meses después se celebrarían las elecciones, iniciándose una nueva era para la política de la república. Y es que cuando en 2002 el partido AKP se alzara victorioso en las elecciones, se iniciaría un proceso que cambiaría la política turca hasta la actualidad. Por un lado, el poder que los militares habían ostentado hasta el momento sería puesto bajo control de una forma que no había ocurrido en los casi 70 años de la república turca. Por otro, la cuestión kurda se pondría sobre la mesa con el diálogo de por medio, un cambio fundamental tras una guerra de casi 20 años que se había cobrado decenas de miles de vidas. En definitiva, los discursos frente a temas fundamentales en la historia política turca cambiarían radicalmente.

También respecto a la cuestión aleví habría novedades, pues sería el primer gobierno de la historia de Turquía en tomarse en serio oficialmente el problema aleví. Esta postura se vería plasmada en lo que se denominó el “Alevi Opening” (la Apertura Aleví), celebrándose distintos talleres y reuniones entre los representantes de la comunidad aleví y los miembros del gobierno, llegando a participar el propio Erdogan en una de las celebraciones de ruptura del ayuno aleví. No obstante, las verdaderas intenciones del líder turco pronto saldrían a la luz, comprobándose que la verdadera voluntad del partido AKP era más la asimilación dentro de la mayoría suní que el reconocimiento de los derechos de la minoría. Así, las cemevi siguen siendo consideradas meros centros culturales –a pesar de que el Directorio de Asuntos Religiosos se financia con los impuestos de todos los habitantes de Turquía, alevíes incluidos– y las llamadas de atención que el Tribunal Europeo de Derechos Humanos ha dado a Turquía respecto a esta cuestión –por ejemplo, respecto a la discriminación que sufren los alevíes en las escuelas al ser obligados a aceptar el programa educativo de religión, exclusivamente suní– no han tenido ningún resultado. Asimismo, la identidad religiosa de los alevíes continuaría utilizándose como arma política contra la oposición y las protestas sociales, dándose casos de puros insultos hacia la comunidad.

Por último, la masiva participación de los alevíes en las protestas sociales que estallaron en 2013, las llamadas protestas de Gezi, su posicionamiento junto a los partidos de izquierda y de oposición frente al conservadurismo de Erdogan, así como la perseverancia de la comunidad en seguir reclamando sus derechos y la postura contraria que han manifestado respecto a la postura del gobierno turco en Siria, han acentuado el antagonismo entre los alevíes y el AKP.

En definitiva, la lucha de la comunidad aleví deberá continuar. No obstante, los esfuerzos asimilatorios de un partido AKP cada vez más beligerante contra el disentimiento interno, dispuesto a fomentar fracturas sociales de todo tipo para asegurar su mantenimiento en las estructuras de poder, no parece presentar un panorama optimista a corto plazo para las reivindicaciones de los alevíes.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

In the spring of 2006, Gerard Russell was a bored British diplomat stewing in the heat of the Green Zone in Baghdad, “a five-mile 21st-century dystopia filled with concrete berms and highway bridges that ended in midair where a bomb had cleaved them”. Then he received a call from the high priest of the Mandeans.

In the spring of 2006, Gerard Russell was a bored British diplomat stewing in the heat of the Green Zone in Baghdad, “a five-mile 21st-century dystopia filled with concrete berms and highway bridges that ended in midair where a bomb had cleaved them”. Then he received a call from the high priest of the Mandeans.

Over zijn gewezen partij lezen we iets anders. ‘De alomtegenwoordigheid van de religie in de jeugdjaren en de opleiding van heel veel partijleden verklaart heel veel van de verkramping waarvan Groen tot op heden blijk geeft in elke discussie over multiculturalisme en islam.’ Het lijkt niet echt te kloppen met wat hij over zijn exit bij Groen zei in

Over zijn gewezen partij lezen we iets anders. ‘De alomtegenwoordigheid van de religie in de jeugdjaren en de opleiding van heel veel partijleden verklaart heel veel van de verkramping waarvan Groen tot op heden blijk geeft in elke discussie over multiculturalisme en islam.’ Het lijkt niet echt te kloppen met wat hij over zijn exit bij Groen zei in

John Calvin (1509-1564) appeared as a player on the historical stage during an intense developmental period for Western civilization. The Roman Catholic Church had wielded power in the West for over a millennium, and during that time it had become increasingly corrupt as an institution – so much so that by the 16th century the Church hierarchy was funded (to a large degree) by a direct marketing scheme known as “indulgences.” How the indulgences worked were as follows: No matter how grievously someone might have “sinned,” one could buy a piece of paper signed by either a Bishop or a Cardinal, which guaranteed a place in heaven for that particular person or a loved one of the person’s own choosing. These “get-out-of-hell-free” cards were sold by members of the clergy through franchises granted by the Church hierarchy. The typical indulgence erased one’s previous sins, but for a larger fee there was a twisted kind of“super”indulgence which erased any future sins one might commit as well, no matter how great or blasphemous.

John Calvin (1509-1564) appeared as a player on the historical stage during an intense developmental period for Western civilization. The Roman Catholic Church had wielded power in the West for over a millennium, and during that time it had become increasingly corrupt as an institution – so much so that by the 16th century the Church hierarchy was funded (to a large degree) by a direct marketing scheme known as “indulgences.” How the indulgences worked were as follows: No matter how grievously someone might have “sinned,” one could buy a piece of paper signed by either a Bishop or a Cardinal, which guaranteed a place in heaven for that particular person or a loved one of the person’s own choosing. These “get-out-of-hell-free” cards were sold by members of the clergy through franchises granted by the Church hierarchy. The typical indulgence erased one’s previous sins, but for a larger fee there was a twisted kind of“super”indulgence which erased any future sins one might commit as well, no matter how great or blasphemous.

Ainsi, si le musulman devrait se fondre aveuglément dans l'oummah et se soumettre à la nécessité d'une communauté des croyants sans faille, pour la gloire de l'islam, il s'avère que des réflexes éthnico-culturels, même immergés, refassent surface, sous certaines conditions et situations particulières, offrent des choix spécifiques, provoquent des attitudes éthniques, étatiques, régionales, tribales, claniques ou familiales, divergentes de celles espérées et reconnues par l'oummah : la réalité et la force de ces açabiyya vient souvent limiter ou tempérer le monolithisme effectif de l'oummah.

Ainsi, si le musulman devrait se fondre aveuglément dans l'oummah et se soumettre à la nécessité d'une communauté des croyants sans faille, pour la gloire de l'islam, il s'avère que des réflexes éthnico-culturels, même immergés, refassent surface, sous certaines conditions et situations particulières, offrent des choix spécifiques, provoquent des attitudes éthniques, étatiques, régionales, tribales, claniques ou familiales, divergentes de celles espérées et reconnues par l'oummah : la réalité et la force de ces açabiyya vient souvent limiter ou tempérer le monolithisme effectif de l'oummah.

Mr. ‘Abd al-Rahman holds similar positions. He writes: “The very existence of a threat to the social order is in itself justification for the overthrow of the regime” (p. 350). It is important to bear in mind that the word “regime” is not qualified. The “regime” could thus be any regime under which Muslims live. One must always keep in mind the basic fact that Islamists are intent on world domination, on implementing theocracy wherever they reside, even when it seems as if they are engaged in purely nationalist struggle, as is the case with Hamas, an organization that devotes itself to the Palestinian cause and freely uses nationalist rhetoric. Article 5 of the Hamas Charter states:

Mr. ‘Abd al-Rahman holds similar positions. He writes: “The very existence of a threat to the social order is in itself justification for the overthrow of the regime” (p. 350). It is important to bear in mind that the word “regime” is not qualified. The “regime” could thus be any regime under which Muslims live. One must always keep in mind the basic fact that Islamists are intent on world domination, on implementing theocracy wherever they reside, even when it seems as if they are engaged in purely nationalist struggle, as is the case with Hamas, an organization that devotes itself to the Palestinian cause and freely uses nationalist rhetoric. Article 5 of the Hamas Charter states:

Celui qui l’a appris à ses dépens, c’est un Néo-Zélandais, gérant de bar en Birmanie (Myanmar, SVP), un certain Phil Blackwood, condamné à deux ans et demi de prison pour avoir portraituré Bouddha avec des écouteurs sur la tête, juste histoire de faire de la publicité pour son bar, « lounge », évidemment. Eh oui, le bouddhisme, ce n’est pas forcément la fête du slip tous les dimanches. Le Phil Blackwood en question a eu beau s’excuser, battre coulpe et montrer patte blanche : pas de remise de peine et case prison direct.

Celui qui l’a appris à ses dépens, c’est un Néo-Zélandais, gérant de bar en Birmanie (Myanmar, SVP), un certain Phil Blackwood, condamné à deux ans et demi de prison pour avoir portraituré Bouddha avec des écouteurs sur la tête, juste histoire de faire de la publicité pour son bar, « lounge », évidemment. Eh oui, le bouddhisme, ce n’est pas forcément la fête du slip tous les dimanches. Le Phil Blackwood en question a eu beau s’excuser, battre coulpe et montrer patte blanche : pas de remise de peine et case prison direct.

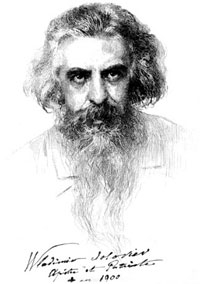

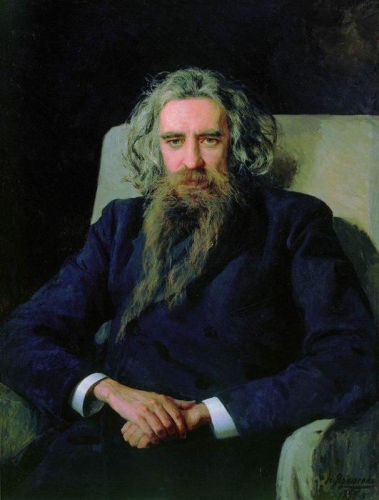

La búsqueda de la unidad a todos los niveles, la «unitotalidad», según la expresión acuñada por él, puede considerarse la piedra angular que sostiene y da coherencia a todo el sistema de este pensador absolutamente original, a menudo paradójico y «extraño», imposible de reducir a los esquemas de la cultura académica. Soloviev, que poseía además de extraordinarias dotes intelectuales una profunda sensibilidad poética, contribuyó más que nadie al renacimiento espiritual ruso del siglo XX, y es autor de la creación especulativa más universal de la edad moderna, una obra tan monumental que le valió el apelativo de «santo Tomás de la Iglesia de Oriente». Sin embargo, como subrayaron los ponentes del encuentro, tal unidad no procede, para Soloviev, de un principio abstracto, un universal teórico o ético, sino de la persona viva de Jesucristo, punto fundamental de su vida y de su pensamiento. A esta presencia viva se dirige Soloviev como hacia el amigo más íntimo y querido, «mi Cristo», criterio de todo lo que el hombre piensa y siente y, sin embargo, irreductible tanto a sentimientos subjetivos como a valores o conceptos abstractos, ya que es inseparable de la Iglesia: «Para nosotros Dios no tiene realidad sin Cristo, Dios-hombre; es más, el mismo Cristo dejaría de ser real para nosotros si no fuera más que un recuerdo histórico: es preciso que se nos revele en el presente. Y esta revelación presente debe ser independiente de nuestra limitación individual. Esta realidad de Cristo y de su vida, independiente de nuestros límites personales, nos es dada en la Iglesia».

La búsqueda de la unidad a todos los niveles, la «unitotalidad», según la expresión acuñada por él, puede considerarse la piedra angular que sostiene y da coherencia a todo el sistema de este pensador absolutamente original, a menudo paradójico y «extraño», imposible de reducir a los esquemas de la cultura académica. Soloviev, que poseía además de extraordinarias dotes intelectuales una profunda sensibilidad poética, contribuyó más que nadie al renacimiento espiritual ruso del siglo XX, y es autor de la creación especulativa más universal de la edad moderna, una obra tan monumental que le valió el apelativo de «santo Tomás de la Iglesia de Oriente». Sin embargo, como subrayaron los ponentes del encuentro, tal unidad no procede, para Soloviev, de un principio abstracto, un universal teórico o ético, sino de la persona viva de Jesucristo, punto fundamental de su vida y de su pensamiento. A esta presencia viva se dirige Soloviev como hacia el amigo más íntimo y querido, «mi Cristo», criterio de todo lo que el hombre piensa y siente y, sin embargo, irreductible tanto a sentimientos subjetivos como a valores o conceptos abstractos, ya que es inseparable de la Iglesia: «Para nosotros Dios no tiene realidad sin Cristo, Dios-hombre; es más, el mismo Cristo dejaría de ser real para nosotros si no fuera más que un recuerdo histórico: es preciso que se nos revele en el presente. Y esta revelación presente debe ser independiente de nuestra limitación individual. Esta realidad de Cristo y de su vida, independiente de nuestros límites personales, nos es dada en la Iglesia».

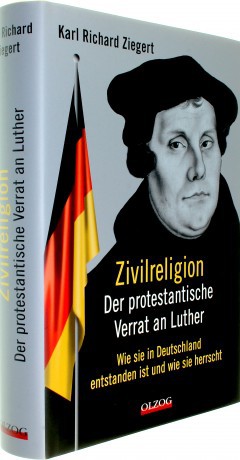

Der evangelische Theologe Karl Richard Ziegert untersucht und kritisiert ausführlich die Rolle der Evangelischen Kirche in Deutschland bei der Entstehung der bundesdeutschen Zivilreligion.

Der evangelische Theologe Karl Richard Ziegert untersucht und kritisiert ausführlich die Rolle der Evangelischen Kirche in Deutschland bei der Entstehung der bundesdeutschen Zivilreligion.