Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

The heterogeneity of America’s European population has always posed a challenge to its national identity. Only late in the nineteenth century was this identity extended to European immigrants assimilated in its Anglo-Protestant values and, in the twentieth century, to Catholics, whose Church (the “Whore of Babylon”) had learned to accommodate the Protestant contours of American life (or what John Murray Cuddihy called its “civil religion”). From this ethnogenesis, the original Anglo-Protestant identity of the American people gradually evolved into a more inclusive European Christian identity, though one closely tied to its Anglo-Protestant antecedents.

The heterogeneity of America’s European population has always posed a challenge to its national identity. Only late in the nineteenth century was this identity extended to European immigrants assimilated in its Anglo-Protestant values and, in the twentieth century, to Catholics, whose Church (the “Whore of Babylon”) had learned to accommodate the Protestant contours of American life (or what John Murray Cuddihy called its “civil religion”). From this ethnogenesis, the original Anglo-Protestant identity of the American people gradually evolved into a more inclusive European Christian identity, though one closely tied to its Anglo-Protestant antecedents.

Based on this heritage, racial nationalists today define America as a European nation and designate its anti-white elites as their principal enemy.

It was, though, but in fits and starts that American whites acquired an ethnonational identity. What’s often referred to as American nationalism—the expansionist slogans of Manifest Destiny, the ideology of Anglo-Saxonism, the gunboat diplomacy of the Progressives (McKinley, T. Roosevelt, Wilson)—was more a chauvinist statism legitimating territorial expansionism and land speculation than an ideological offshoot of the country’s racial-historical life forms. The primordial concerns of the American nation were thus only tangentially represented in these imperialist movements associated with the state’s expansion.

The first genuinely post-revolutionary expression of American ethnonationalism (i.e., “nationalism in its pristine sense”) began, accordingly, with the first wave of mass immigration, in the late 1830s and “the hungry Forties,” as Irish and South German Catholics reached American shores, affronting “Anglo-Americans” with their “otherness.” The “nativists” (native born, White, Protestant Americans) opposing the new immigrants rejected the crime, public drunkenness, pauperism the Irish brought, but above all the Catholicism of both groups, for “the Church of Rome” was an anathema to a liberal nation born of the Reformation and of the struggles against the Catholic empires of Spain and France.

The nativist response was nevertheless a nuanced one recognizing the distinctions that culturally separated Irishmen from Germans. The latter, who began to outnumber the Irish only in the late 1850s, tended to be farmers and artisans. That they settled inland, away from the older coastal settlements, and engaged in respectable occupations also mitigated nativist opposition, though nativists opposed the formation of German-speaking communities, beer-drinking forms of sociability, and the Germans’ political radicalism.

The Germans nevertheless seemed assimilable, which was not the case with the Irish. The first expression of American nativism was thus largely an anti-Irish movement, for the tribal solidarity of this unbourgeois people, their aggressive rejection of Protestant culture, their whiskey drinking and pre-modern behavior, and their anti-liberal sympathy with the slave states (which nativists resented because these states closed off land to white settlement) were an offense to the country’s Anglo-Protestant culture.

This anti-Irish sentiment became especially prominent once the famine ships, with their destitute cargoes, began arriving.

The Irish, though, offended not simply the Yankees’ religious and behavioral standards, their quick exploitation of the political system offended their republican convictions. Though one of the most afflicted of Europe’s nations, Erin’s exiles were also one of the most politically “advanced.” Not only had they a long history of secret societies (such as the Defenders, Whiteboys, Ribbonmen, etc.), which had waged an underground war against English landlords and Orangemen, in the 1820s, Daniel O’Connell’s Catholic Association, “the first mass political party in history,” taught the Irish how to exploit the new electoral forms of liberal parliamentary politics in order to throw off England’s Protestant ascendancy and its genocidal Penal Laws.

In America, the politically savvy Irish (led by their priests, saloon keepers, and eloquent rebels) challenged not just Yankee folkways, but the individualistic tenor of republican governance.

The terrible age of American ethnic politics begins with the Irish.

From the 1830s through to the late 1850s, nativist opposition to Catholic, specifically Irish, immigration took the form of intercommunal strife, the proliferation of anti-immigrant associations, and, then in 1854, the establishment of a national political party—the American Party (known as the “Know-Nothings”)—which, for a time, became a refuge for abolitionist and free-soil opponents of Southern slavery who had broken with the Whig party but not yet affiliated with the newly formed Republican party. (That is, this nativist party was partly the creation of those who now seek our destruction as a people.)

The Know Nothings held that Protestantism was an essential component of American identity; that Catholicism’s “autocratic” Pope and Church hierarchy were incompatible with republican self-rule; that Catholics had acquired undue political advantage; and that a longer, more thorough process of naturalization (Americanization) was necessary for the acquisition of citizenship. More fundamentally, it gave expression to the deep reservation which Anglo-American Protestants had about allowing their country to be overrun by Catholic immigrants.

Like most future manifestations of American racial nationalism (though they lacked a genuinely racial dimension), the Know Nothings were moved by a populist distrust of the state and the established political parties, which were seen as indifferent to the ethnocommunal identity of native whites.

Within but a year of its founding, the American Party succeeded in electing eight state governors, more than a hundred Congressmen, the mayors of Boston, Philadelphia, and Chicago, and thousands of local officials. Its future looked bright.

But the party fell almost as rapidly as it rose, having been swept up and then forced off the political stage by powerful sectional conflicts related to slavery and the preservation of the Union.

Its struggle for an Anglo-Protestant America in the 1850s nevertheless represented the first bloom of American nationalism in its blood-and-soil stage (somewhat earlier than other European nationalisms, which were still at the liberal political stage). As such, it resisted a political system privileging economics over community, opportunity over belief, and a liberal over a biocultural understanding of American life.

Though race was not an issue, religion, culture, and an endogamous sense of community were—issues that are preeminently ethnonationalist. Nativism became, as such, the foundation upon which the future defense of European life in America would be waged—for in however rudimentary and unfocused a way, it defended the American nation as an Anglo-Protestant community of descent, not a political entity based on an abstract ideological or creedal notion of nationality opened to all the world. (We Irish, supreme irony, have, as any roll of white nationalist ranks reveals, become the foremost exponent of this view today.)

The racial component of this biocultural definition of the nation did, though, soon come into its own—in the anti-Chinese movement that dominated California politics in the half century following the Gold Rush (1848).

As European immigrants, native Americans, and the first Chinese made their way to California in this period, so too did racial conflict—though conflict here would not be between natives and immigrants, but between Occidentals and Orientals, White against Yellow.

Standing together against the first Chinese arrivals—and to the swarming millions threatening to follow in their wake—native Americans and Irish Catholics discovered their common racial identity.

Almost from the start, they recognized the joint stake they had in opposing a people which worked at half the white man’s wage, retained their alien clothes, customs, and language, practiced a “heathen” religion, and created distinct, over-crowded, dirty, and often self-contained communities associated with vice and disease.

Comprising more than a fifth of the California labor force in the 1870s, these Chinese newcomers, with their low living standards and servile conditions, were seen as threatening not just the racial definition of the nation, but the American way of life—the prevailing standard for what it meant to be a free white man—and, ultimately, white civilization.

In such a situation, white solidarity was paramount—which meant that, in face of the Yellow Hordes, religious differences dividing Protestant natives and Catholic immigrants in the antebellum period had to be superseded.

Accused of cheapening labor and introducing foreign elements in the East, the Irish were now welcomed into California nativist ranks—as whites facing a common threat—and, accordingly, they came to play a leading role—perhaps the leading role—in spearheading the trade-union, political, and communal opposition to the Chinese.

The extent of white solidarity in the popular classes was such that it spurred numerous official and unofficial measures to restrict Chinese participation in the economy and in other realms of American life.

As early as the 1850s, local and state laws were passed to limit the type of jobs the Chinese could work, the land they could own, and the schools their children could attend, while white, especially Irish, workingmen not infrequently resorted to violence to drive them from certain trades and neighborhoods. In mining, logging, and construction, the Chinese were forced out entirely and in numerous small towns throughout California and the Northwest, Chinese communities were abandoned in face of angry white mobs.

Then, in the late 1870s, in a period of economic crisis, a Workingmen’s Party, led by an Irish demagogue, Denis Kearney, was formed in San Francisco.

Its principal slogan was “The Chinese must go.”

Supported by a mass network of “anti-coolie clubs” and trade unions, the party became the chief vehicle for the cause of Chinese exclusion.

The state organization of the two established national parties, the Democrats and the Republicans, each, for the sake of appeasing the pervasive anti-Chinese sentiment the Workingmen represented, were forced to support its exclusionist policies.

But more than transcending religious and political differences between closely related whites, the Chinese exclusion movement took aim at those large-scale corporate interests (primarily the railroads) responsible for importing Chinese contract labor and using it as leverage against white workers.

In frequent sand-lot demonstrations and in broadsheets, the movement, buttressed by large crowds of male workers, warned the monied men of Judge Lynch, targeting not just alien, but native threats to the nation’s bioculture.

Its slogan—“We want no slaves or aristocrats”—was an “egalitarian” affirmation of the existing racial hierarchy, and of the right of white men to the ownership of the land their people had conquered and created.

The movement’s achievements were momentous. For the first time in modern history, national legislation (to supplant the less effective immigration law of 1790) was passed to prevent non-whites from entering the United States and preventing those already within its borders from setting down roots.

White workers, supported by their trade unions, workingmen associations, and other organized expressions of white power, succeeded in frustrating capitalist and official efforts to change the country’s demographic character. White racial solidarity, at this stage, triumphed over those differences that stemmed from the religious wars of the Reformation.

Racially consciousness, populist, and at times anti-capitalist, the anti-Chinese movement of the 1870s (whose spirit, incidentally, lived on in the national-socialist novels of Jack London) succeeded in preserving the American West as a white Lebens-raum. As I see it (and I see it from both from an Irish and American perspective), it represents the single greatest movement of White America

The third great formative influence affecting the shape of American racial nationalism—though a step back from the anti-Chinese movement—came during the First World War.

The Ku Klux Klan, which had emerged after Appomattox to defend Southern whites from Negro aggression and the Yankee military occupation, was re-organized in 1915 to address certain changes in American life.

Like the European fascist movements of the interwar period, this “Second Klan” constituted a mass populist reaction to the war’s radical cultural/social dislocations.

The war had imbued the central government with unprecedented powers, enabling it to encroach on local communities in ways previously unknown; the recently founded Federal Reserve, in charge of the money supply, and the growing influence of Wall Street and the great corporations assumed an influence in national life that seemed to come at the expense of independent entrepreneurs and “the little men.” At the same time, the war effort assaulted the existing racial, familial, and moral hierarchies.

Blacks in this period acquired a foothold in northern industries and discharged Negro soldiers, “after having seen Paris,” were no longer willing to tolerate their caste status. The year 1919 was accordingly one of unprecedented racial violence, as Negroes challenging the existing system of race relations set off bloody riots in 26 urban centers.

In the same period, the middle-class family came under attack. Suffragettes carried the day with the 19th Amendment, a “new women,” promoted by advertisers and by Hollywood, questioned conventional “gender” relations, divorce rates suddenly shot up, and children were increasingly exposed to anti-traditionalist influences.

Finally, there was the specter of Bolshevism, which appealed to the unassimilated communities of recently arrived Eastern and Southern European immigrants (only 10 percent of the CPUSA membership could speak English by the mid-1920s) and assumed a menacing form in the great industrial conflicts that swept up more than a fifth of the national workforce.

On every front, then, it seemed as if small-town, rural, and middle-class White America was in retreat.

But not before making a last—and, for a generation, successful—stand in its defense, for within a decade of its founding, the Klan had rallied 5 million members to its ranks, penetrating local and national power-structures as few other anti-liberal movements in US history.

Comprised of white, native-born, anti-immigrant, anti-Catholic, and anti-Jewish elements, particularly in the South and the Midwest, this “Second Klan” saw itself as an “army of Protestant Americans.” As such, it sought to defend “pure Americanism, old-time religion, and conventional Protestant morality”—in the process reviving those religious issues that had earlier divided whites along sectarian lines (like in the 1850s), yet at the same time attempting to preserve the hegemony of Anglo-Protestants against the forces seeking to subvert the nation’s historic ethnic core.

To the degree the Klan was more sectarian than racial, favoring the conformist, materialist, and philistine elements in American life, it was a step back from the white consciousness of the anti-Chinese movement. (A similar phenomenon occurred after the Second World War among recently assimilated, often Catholic, immigrants, whose support for Joseph McCarthy was part of a more general effort to demonstrate that the “Americanism” of the “old immigrants,” largely Irish and German, was superior to that of the established but liberal and cosmopolitan Anglo-Protestant elite).

The Klan (like McCarthyism) was nevertheless not entirely the “reactionary” movement that academic historians make of it, for like its European counterpart, it was both traditionalist and populist, favoring measures that were anti-liberal, anti-cosmopolitan, and anti-egalitarian in spirit but by no means regressive.

In this capacity, it forced the government to close the border to immigration, it beat back the black assault on white hegemony, it let the wheeler-dealers in Washington and New York know that their “progressive policies” would not go unchallenged in the Heartland, and it acted as a moral bulwark against the permissive forces of Hollywood and Madison Avenue.

Above all, it upheld a racial standard for American existence.

Only in the late 1920s, after successfully preserving many traditional areas of American life that might otherwise had succumbed to the race-mixing modernism of the postwar “Jazz Age” did the movement finally subside in face of the economic breakdown of the 1930s.

* * *

The history of American racial nationalism, as exemplified by the Second Klan, the Chinese exclusion movement, and the early nativists, is a history whose legacy has, in the last half century, been squandered and suppressed by the elites now controlling American destinies.

Yet this is the legacy that the heirs of European-America today, if they are to survive, need to reclaim.

For this history confirms them in their belief that the popular classes in America have always rejected the creedal definition of the nation; that they refused to allow their society and territory to be overrun by non-whites; and that divisive sectarian issues (between Protestants and Catholics, leftists and rightists, modernists and traditionalists, etc.) served only the interest of their enemies.

Most of all, this heritage of American ethnonationalism calls on whites today, in this era of their dispossession, to defend the racial-cultural-civilizational “nation” to which they once belonged and which, if regained, might again distinguish them from the world’s less favored races.

Unlike Edmund Burke and Joseph de Maistre, Louis de Bonald devoted little space to analyzing the French Revolution itself. His focus instead was on understanding the traditional society which had been swept away. His review of Mme. de Staël’s Considerations on the Principal Events of the French Revolution

Unlike Edmund Burke and Joseph de Maistre, Louis de Bonald devoted little space to analyzing the French Revolution itself. His focus instead was on understanding the traditional society which had been swept away. His review of Mme. de Staël’s Considerations on the Principal Events of the French Revolution, e.g., ends up turning into a theory of the nobility and its function. Bonald scholar Christopher Olaf Blum calls this “his most original contribution to the theory of the counter-revolution.”

, p. 92ff. Bonald’s views on this matter are quite similar to Hegel’s.)

than to the ideal type described by Bonald. As Blum says, “in making [his] argument, [Bonald] was a reformer, for the French nobility had shown itself willing to jettison its duties in favor of the kind of freedom that would enable them, the wealthy, to dominate more effectively and without the hindrance of traditional strictures.”

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Son tiempos estos los que corren donde el heroísmo y la entrega, sacrificando para ello su vida si fuera preciso, es considerado un acto de idealismo estúpido; época la nuestra en que la Juventud, en mayúscula, ha dejado de tener sentido para convertirse en una mera comparsa de la sociedad de consumo. Parece que esta edad es más una técnica de mercado. El desánimo cunde entre las filas de aquellos que aún ven, nadie cree que exista el menor resquicio por donde destruir esta desidia colectiva. Muchos se resguardan en la nostalgia y en los recuerdos de años pasados, incluso los más jóvenes que no lo vivimos nos aislamos y preferimos las glorias del pasado a la dura lucha del día a día por rescatarlo. Es más fácil.

Son tiempos estos los que corren donde el heroísmo y la entrega, sacrificando para ello su vida si fuera preciso, es considerado un acto de idealismo estúpido; época la nuestra en que la Juventud, en mayúscula, ha dejado de tener sentido para convertirse en una mera comparsa de la sociedad de consumo. Parece que esta edad es más una técnica de mercado. El desánimo cunde entre las filas de aquellos que aún ven, nadie cree que exista el menor resquicio por donde destruir esta desidia colectiva. Muchos se resguardan en la nostalgia y en los recuerdos de años pasados, incluso los más jóvenes que no lo vivimos nos aislamos y preferimos las glorias del pasado a la dura lucha del día a día por rescatarlo. Es más fácil.

(1) Sur le salut nazi, Fabrice Bouthillon affirme : «Ce geste fasciste par excellence, qu’est le salut de la main tendue, n’est-il pas au fond né à Gauche ? N’a-t-il pas procédé d’abord de ces votes à main levée dans les réunions politiques du parti, avant d’être militarisé ensuite par le raidissement du corps et le claquement des talons – militarisé et donc, par là, droitisé, devenant de la sorte le symbole le plus parfait de la capacité nazie à faire fusionner, autour de Hitler, valeurs de la Gauche et valeurs de la Droite ? Car il y a bien une autre origine possible à ce geste, qui est la prestation de serment le bras tendu; mais elle aussi est, en politique, éminemment de Gauche, puisque le serment prêté pour refonder, sur l’accord des volontés individuelles, une unité politique dissoute, appartient au premier chef à la liste des figures révolutionnaires obligées, dans la mesure même où la dissolution du corps politique, afin d’en procurer la restitution ultérieure, par l’engagement unanime des ex-membres de la société ancienne, est l’acte inaugural de toute révolution. Ainsi s’explique que la prestation du serment, les mains tendues, ait fourni la matière de l’une des scènes les plus topiques de la révolution française – et donc aussi, qu’on voie se dessiner, derrière le tableau par Hitler du meeting de fondation du parti nazi, celui, par David, du Serment du Jeu de Paume» (p. 171).

(1) Sur le salut nazi, Fabrice Bouthillon affirme : «Ce geste fasciste par excellence, qu’est le salut de la main tendue, n’est-il pas au fond né à Gauche ? N’a-t-il pas procédé d’abord de ces votes à main levée dans les réunions politiques du parti, avant d’être militarisé ensuite par le raidissement du corps et le claquement des talons – militarisé et donc, par là, droitisé, devenant de la sorte le symbole le plus parfait de la capacité nazie à faire fusionner, autour de Hitler, valeurs de la Gauche et valeurs de la Droite ? Car il y a bien une autre origine possible à ce geste, qui est la prestation de serment le bras tendu; mais elle aussi est, en politique, éminemment de Gauche, puisque le serment prêté pour refonder, sur l’accord des volontés individuelles, une unité politique dissoute, appartient au premier chef à la liste des figures révolutionnaires obligées, dans la mesure même où la dissolution du corps politique, afin d’en procurer la restitution ultérieure, par l’engagement unanime des ex-membres de la société ancienne, est l’acte inaugural de toute révolution. Ainsi s’explique que la prestation du serment, les mains tendues, ait fourni la matière de l’une des scènes les plus topiques de la révolution française – et donc aussi, qu’on voie se dessiner, derrière le tableau par Hitler du meeting de fondation du parti nazi, celui, par David, du Serment du Jeu de Paume» (p. 171). Che

Che

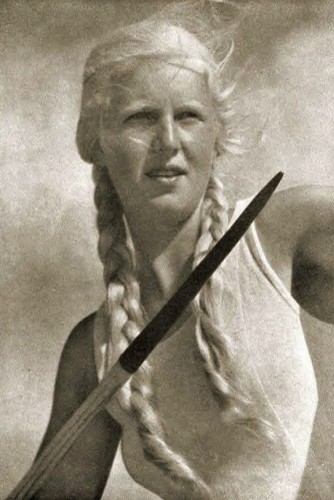

National Socialism promoted two images of woman: the hardworking peasant mother in traditional dress, and the uniformed woman in service to her people. Both images were an attempt to combat two types of woman that are foreign to Traditional European societies: the Aphrodisian and Amazonian woman.

National Socialism promoted two images of woman: the hardworking peasant mother in traditional dress, and the uniformed woman in service to her people. Both images were an attempt to combat two types of woman that are foreign to Traditional European societies: the Aphrodisian and Amazonian woman. These were the Aphrodisian elements that had made their way into the Weimar Republic and Third Reich, and which the National Socialists tried to restrain, along with modern Amazonian woman (the unmarried, childless, career woman in mannish dress). The Aphrodite type was represented by the “movie ‘star’ or some similar fascinating Aphrodisian apparition.”[6] In his introduction to the writings of Bachofen, National Socialist scholar Alfred Baeumler wrote that the modern world has all of the characteristics of a gynaecocratic age. In writing about the European city-woman, he says, “The fascinating female is the idol of our times, and, with painted lips, she walks through the European cities as she once did through Babylon.”[7]

These were the Aphrodisian elements that had made their way into the Weimar Republic and Third Reich, and which the National Socialists tried to restrain, along with modern Amazonian woman (the unmarried, childless, career woman in mannish dress). The Aphrodite type was represented by the “movie ‘star’ or some similar fascinating Aphrodisian apparition.”[6] In his introduction to the writings of Bachofen, National Socialist scholar Alfred Baeumler wrote that the modern world has all of the characteristics of a gynaecocratic age. In writing about the European city-woman, he says, “The fascinating female is the idol of our times, and, with painted lips, she walks through the European cities as she once did through Babylon.”[7] The earliest Europeans tended toward simplicity in dress and appearance. Adornments were used solely to signify caste or heroic deeds, or were amulets or talismans. In ancient Greece, jewels were never worn for everyday use, but reserved for special occasions and public appearances. In Rome, also, jewelry was thought to have a spiritual power.[11] Western fashion often was used to display rank, as in Roman patricians’ purple sash and red shoes. The Mediterranean cultures, influenced by the East, were the first to become extravagant in dress and makeup. By the time this influence spread to northern Europe, it had been Christianized, and makeup did not appear again in northern Europe until the fourteenth century, after which followed a long period of its association with immorality.[12]

The earliest Europeans tended toward simplicity in dress and appearance. Adornments were used solely to signify caste or heroic deeds, or were amulets or talismans. In ancient Greece, jewels were never worn for everyday use, but reserved for special occasions and public appearances. In Rome, also, jewelry was thought to have a spiritual power.[11] Western fashion often was used to display rank, as in Roman patricians’ purple sash and red shoes. The Mediterranean cultures, influenced by the East, were the first to become extravagant in dress and makeup. By the time this influence spread to northern Europe, it had been Christianized, and makeup did not appear again in northern Europe until the fourteenth century, after which followed a long period of its association with immorality.[12]

Il suo nome ai più non dirà molto. Ma Niccolò Giani fu uno dei più importanti, radicali e oltranzisti esponenti del Fascismo rivoluzionario. Fu, infatti, tra i fondatori, nonché uno dei massimi rappresentanti, della Scuola di Mistica Fascista (SMF). Vissuto il suo ideale fino all’ultimo respiro, morì combattendo sul fronte greco nel 1941, ricevendo, per l’esempio offerto, la medaglia d’oro al valore. Tutto questo, mentre molti “fascisti” – le virgolette sono d’obbligo – s’imboscavano in patria, nascondendosi dietro la retorica di vuoti slogan e sterili parole d’ordine. Quegli stessi che, dopo il 1945, seppero bene in che direzione riciclarsi.

Il suo nome ai più non dirà molto. Ma Niccolò Giani fu uno dei più importanti, radicali e oltranzisti esponenti del Fascismo rivoluzionario. Fu, infatti, tra i fondatori, nonché uno dei massimi rappresentanti, della Scuola di Mistica Fascista (SMF). Vissuto il suo ideale fino all’ultimo respiro, morì combattendo sul fronte greco nel 1941, ricevendo, per l’esempio offerto, la medaglia d’oro al valore. Tutto questo, mentre molti “fascisti” – le virgolette sono d’obbligo – s’imboscavano in patria, nascondendosi dietro la retorica di vuoti slogan e sterili parole d’ordine. Quegli stessi che, dopo il 1945, seppero bene in che direzione riciclarsi.

Dans le cadre de la Contrée de cités, les cités fortifiées se situent à une distance comprise entre 40 et 60 km les unes des autres. Le lieu de construction choisi se révèle toujours sec et plat, surélevé de quelques mètres au-dessus du niveau de l'eau, et délimité sur ses côtés par des fleuves et des pentes naturels. Grâce à des recherches archéologiques récentes et à l'observation de photographies aériennes, il a été possible de reconnaître la succession précise des divers systèmes d'aménagements : les structures de forme ovale sont les plus anciennes, remplacées plus tardivement par des structures en forme de cercle ; enfin, les systèmes de fortification rectangulaires sont les plus récents.

Dans le cadre de la Contrée de cités, les cités fortifiées se situent à une distance comprise entre 40 et 60 km les unes des autres. Le lieu de construction choisi se révèle toujours sec et plat, surélevé de quelques mètres au-dessus du niveau de l'eau, et délimité sur ses côtés par des fleuves et des pentes naturels. Grâce à des recherches archéologiques récentes et à l'observation de photographies aériennes, il a été possible de reconnaître la succession précise des divers systèmes d'aménagements : les structures de forme ovale sont les plus anciennes, remplacées plus tardivement par des structures en forme de cercle ; enfin, les systèmes de fortification rectangulaires sont les plus récents. de la Contrée de cités possèdent deux fonctions bien distinctes : utilitaire et sémantique. La poterie, par exemple, est ornée de motifs géométriques qui symbolisent les différentes forces de la nature - cercles, carrés, losanges, triangles, croix gammées - qui se retrouvent également dans l'aspect général des colonies et des constructions tombales. D'autres objets sont également décorés : il s'agit de petites sculptures anthropomorphes et zoomorphes en pierre, de pilons, de coupes en pierre ou de manches d'armes et d'outils.

de la Contrée de cités possèdent deux fonctions bien distinctes : utilitaire et sémantique. La poterie, par exemple, est ornée de motifs géométriques qui symbolisent les différentes forces de la nature - cercles, carrés, losanges, triangles, croix gammées - qui se retrouvent également dans l'aspect général des colonies et des constructions tombales. D'autres objets sont également décorés : il s'agit de petites sculptures anthropomorphes et zoomorphes en pierre, de pilons, de coupes en pierre ou de manches d'armes et d'outils.

Les communautés de la Contrée de cités se divisaient de manière tripartite en guerriers, prêtres et artisans, comme c'est typiquement le cas au sein des sociétés indo-européennes. On ne peut toutefois reconnaître l'existence d'un pouvoir détenu par un chef de tribu unique : grâce aux études menées sur les rites funéraires et les sépultures, il a été possible de conclure que la société de la Contrée de cités était en fait hiérarchisée et rassemblée autour d'une élite. L'autorité de ce groupe d'individus n'était pas fondée sur des contraintes économiques mais sur des valeurs religieuses traditionnelles. Les membres de l'élite tenaient le rôle de prêtres et disposaient également d'une position importante dans le domaine militaire. La femme possédait un statut social élevé et la part jouée d'une manière générale par les femmes dans la culture de la Contrée de cités était très développée.

Les communautés de la Contrée de cités se divisaient de manière tripartite en guerriers, prêtres et artisans, comme c'est typiquement le cas au sein des sociétés indo-européennes. On ne peut toutefois reconnaître l'existence d'un pouvoir détenu par un chef de tribu unique : grâce aux études menées sur les rites funéraires et les sépultures, il a été possible de conclure que la société de la Contrée de cités était en fait hiérarchisée et rassemblée autour d'une élite. L'autorité de ce groupe d'individus n'était pas fondée sur des contraintes économiques mais sur des valeurs religieuses traditionnelles. Les membres de l'élite tenaient le rôle de prêtres et disposaient également d'une position importante dans le domaine militaire. La femme possédait un statut social élevé et la part jouée d'une manière générale par les femmes dans la culture de la Contrée de cités était très développée.

Nazi Fashion Wars:

The Evolian Revolt Against Aphroditism in the Third Reich, Part 2

Judaism is not historically opposed to cosmetics and jewelry, although two stories can be interpreted as negative indictments on cosmetics and too much finery: Esther rejected beauty treatments before her presentation to the Persian king, indicating that the highest beauty is pure and natural; and Jezebel, who dressed in finery and eye makeup before her death, may the root of some associations between makeup and prostitutes.

In most cases, however, Jewish views on cosmetics and jewelry tend to be positive and indicate woman’s role as sexual: “In the rabbinic culture, ornamentation, attractive dress and cosmetics are considered entirely appropriate to the woman in her ordained role of sexual partner.” In addition to daily use, cosmetics also are allowed on holidays on which work (including painting, drawing, and other arts) are forbidden; the idea is that since it is pleasurable for women to fix themselves up, it does not fall into the prohibited category of work.[1]

In addition to the historical distinctions between cultures on cosmetics, jewelry, and fashion, the modern era has demonstrated that certain races enter industries associated with the Aphrodisian worldview more than others. Overwhelmingly, Jews are overrepresented in all of these arenas. Following World War I, the beauty and fashion industries became dominated by huge corporations, many of the Jewish-owned. Of the four cosmetics pioneers — Helena Rubenstein, Elizabeth Arden, Estée Lauder (née Mentzer), and Charles Revson (founder of Revlon) — only Elizabeth Arden was not Jewish. In addition, more than 50 percent of department stores in America today were started or run by Jews. (Click here for information about Jewish department stores and jewelers, and here for Jewish fashion designers).

Hitler was not the only one who noticed Jewish influence in fashion and thought it harmful. Already in Germany, a belief existed that Jewish women were “prone to excess and extravagance in their clothing.” In addition, Jews were accused of purposefully denigrating women by designing immoral, trashy clothing for German women.[2] There was an economic aspect to the opposition of Jews in fashion, as many Germans thought them responsible for driving smaller, German-owned clothiers out of business. In 1933, an organization was founded to remove Jews from the Germany fashion industry. Adefa “came about not because of any orders emanating from high within the state hierarchy. Rather, it was founded and membered by persons working in the fashion industry.”[3] According to Adefa’s figures, Jewish participation was 35 percent in men’s outerwear, hats, and accessories; 40 percent in underclothing; 55 percent in the fur industry; and 70 percent in women’s outerwear.[4]

Although many Germans disliked the Jewish influence in beauty and fashion, it was recognized that the problem was not so much what particular foreign race was impacting German women, but that any foreign influence was shaping their lives and altering their spirit. The Nazis obviously were aware of the power of dress and beauty regimes to impact the core of woman’s self-image and being. According to Agnes Gerlach, chairwoman for the Association for German Women’s Culture:

Not only is the beauty ideal of another race physically different, but the position of a woman in another country will be different in its inclination. It depends on the race if a woman is respected as a free person or as a kept female. These basic attitudes also influence the clothes of a woman. The southern ‘showtype’ will subordinate her clothes to presentation, the Nordic ‘achievement type’ to activity. The southern ideal is the young lover; the Nordic ideal is the motherly woman. Exhibitionism leads to the deformation of the body, while being active obligates caring for the body. These hints already show what falsifying and degenerating influences emanate from a fashion born of foreign law and a foreign race.[5]

Gerlach’s statements echo descriptions of Aphrodisian cultures entirely: Some cultures view women as a sex object, and elements of promiscuity run through all areas of women’s dress and toilette; Aryan cultures have a broader understanding of the possibilities of the female being and celebrate woman’s natural beauty.

The Introduction of Aphrodisian Elements into Germany and the Beginning of the Fashion Battles

Long before the Third Reich, Germans battled the French on the field of fashion; it was a battle between the Aphrodisian culture that had made its way to France, and the Demetrian placement of woman as a wife and mother. As early as the 1600s, German satirical picture sheets were distributed that showed the “Latin morals, manners, customs, and vanity” of the French as threatening Nordic culture in Germany. In the twentieth century, Paris was the height of high fashion, and as tensions between the two countries increased, the French increased their derogatory characterizations of German women for not being stereotypically Aphrodisian. In 1914, a Parisian comic book presented Germans as “a nation of fat, unrefined, badly dressed clowns.”[6] And in 1917, a French depiction of “Virtuous Germania” shows her as “a fat, large-breasted, mean-looking woman, with a severe scowl on her chubby face.”[7]

Hitler saw the French fashion conglomerate as a manifestation of the Jewish spirit, and it was common to hear that Paris was controlled by Jews. Women were discouraged from wearing foreign modes of dress such as those in the Jewish and Parisian shops: “Sex appeal was considered to be ‘Jewish cosmopolitanism’, whilst slimming cures were frowned upon as counter to the birth drive.”[8] Thus, the Nazis staunch stance against anything French was in part a reaction to the Latin qualities of French culture, which had migrated to the Mediterranean thousands of years earlier, and that set the highest image of woman as something German men did not want: “a frivolous play toy that superficially only thinks about pleasure, adorns herself with trinkets and spangles, and resembles a glittering vessel, the interior of which is hollow and desolate.”[9] Such values had no place in National Socialism, which promoted autarky, frugalness, respect for the earth’s resources, natural beauty, a true religiosity (Christian at first, with the eventual goal to return to paganism), devotion to higher causes (such as to God and the state), service to one’s community, and the role of women as a wife and mother.

Opposition to the Aphrodisian Culture in the Third Reich

Most students of Third Reich history are familiar with the more popular efforts to shape women’s lives: the Lebensborn program for unwed mothers, interest-free loans for marriage and children, and propaganda posters that emphasized health and motherhood. But some of the largest battles in the fight for women occurred almost entirely within the sphere of fashion—in magazines, beauty salons, and women’s organizations.

The Nazis did not discount fashion, only its Aphrodisian manifestations. On the contrary, they understood fashion as a powerful political tool in shaping the mores of generations of women. Fashion and beauty also were recognized as important elements in the cultural revolution that is necessary for lasting political change. German author Stafan Zweig commented on fashion in the 1920s:

Today its dictatorship becomes universal in a heartbeat. No emperor, no khan in the history of the world ever experienced a similar power, no spiritual commandment a similar speed. Christianity and socialism required centuries and decades to win their followings, to enforce their commandments on as many people as a modern Parisian tailor enslaves in eight days.[10]

Thus, Nazi Germany established a fashion bureau and numerous women’s organizations as active forces of cultural hegemony. Gertrud Scholtz-Klink, the national leader of the NS-Frauenschaft (NSF, or National Socialist Women’s League), said the organization’s aim was to show women how their small actions could impact the entire nation.[11] Many of these “small actions” involved daily choices about dress, shopping, health, and hygiene.

The biggest enemies of women, according to the Nazi regime, were those un-German forces that worked to denigrate the German woman. These included Parisian high fashion and cosmetics, Jewish fashion, and the Hollywood image of the heavily made up, cigarette-smoking vamp—the archetype of the Aphrodisian. These forces not only impacted women’s clothing, personal care choices, and activities, but were dangerous since they touched the German woman’s very spirit.

Clothing should not now suddenly return to the Stone Age; one should remain where we are now. I am of the opinion that when one wants a coat made, one can allow it to be made handsomely. It doesn’t become more expensive because of that. . . . Is it really something so horrible when [a woman] looks pretty? Let’s be honest, we all like to see it.[14]

Though understanding the need for tasteful and beautiful dress, the Nazis were adamantly against elements foreign to the Nordic spirit. The list included foreign fashion, trousers, provocative clothing, cosmetics, perfumes, hair alterations (such as coloring and permanents), extensive eyebrow plucking, dieting, alcohol, and smoking. In February 1916, the government issued a list of “forbidden luxury items” that included foreign (i.e., French) cosmetics and perfumes.[15] Permanents and hair coloring were strongly discouraged. Although the Nazis were against provocative clothing in everyday dress, they encouraged sportiness and were certainly not prudish about young girls wearing shorts to exercise. A parallel can be seen in the scanty dress worn by Spartan girls during their exercises, a civilization characterized by its Nordic spirit and solar-orientation.

Some have said that Hitler was opposed to cosmetics because of his vegetarian leanings, since cosmetics were made from animal byproducts. More likely, he retained the same views that kept women from wearing makeup for centuries in Western countries—the innate understanding that the Aphrodisian woman is opposed to Aryan culture. Nazi proponents said “red lips and painted cheeks suited the ‘Oriental’ or ‘Southern’ woman, but such artificial means only falsified the true beauty and femininity of the German woman.”[16] Others said that any amount of makeup or jewelry was considered “sluttish.”[17] Magazines in the Third Reich still carried advertisements for perfumes and cosmetics, but articles started advocating minimal, natural-looking makeup, for the truth was that most women were unable to pull off a fresh and healthy image without a little help from cosmetics.

Although jewelry and cosmetics were not banned, many areas of the Third Reich were impossible to enter unless conforming to Nazi ideals. In 1933, “painted” women were banned from Kreisleitung party meetings in Breslau. Women in the Lebensborn program were not allowed to use lipstick, pluck their eyebrows, or paint their nails.[18] When in uniform, women were forbidden to wear conspicuous jewelry, brightly colored gloves, bright purses, and obvious makeup.[19] The BDM also was influential in shaping fashion in the regime, with young girls taking up the use of clever pejoratives to reinforce the regime’s message that unnatural beauty was not Aryan. The Reich Youth Leader said:

The BDM does not subscribe to the untruthful ideal of a painted and external beauty, but rather strives for an honest beauty, which is situated in the harmonious training of the body and in the noble triad of body, soul, and mind. Staunch BDM members whole-heartedly embraced the message, and called those women who cosmetically tried to attain the Aryan female ideal ‘n2 (nordic ninnies)’ or ‘b3 (blue-eyed, blonde blithering idiots).’[20]

The Nazis offered many alternatives to Aphrodisian values: beauty would be derived from good character, exercise outdoors, a good diet, healthy skin free of the harsh chemicals in makeup, comfortable (yet still stylish and flattering) clothing, and from the love for her husband, children, home, and country. The most encouraged hairstyles were in buns or plaits—styles that saved money on trips to the beauty salon and were seen as more wholesome and befitting of the German character. In fact, Tracht (traditional German dress) was viewed as not merely clothing, but also as “the expression of a spiritual demeanor and a feeling of worth . . . Outwardly, it conveys the expression of the steadfastness and solid unity of the rural community.”[21] Foreign clothing designs, according to Gerlach, led to physical and “psychological distortion and damage, and thereby to national and racial deterioration.”[22]

* * *

Some people may be inclined to interpret Aphrodisian culture as positive for the sexes—it puts the emphasis for women not on careers but on their existence as sexual beings. Men often encourage such behavior by their dating choices and by complimenting an Aphrodisian “look” in women. But Aphrodisian culture is not only damaging to women, as Bachofen relates, by reducing them to the status of sex slave of multiple men. It also is degrading for men, at the level of personality and at the deepest levels of being. As Evola writes about the degeneration into Aphroditism:

The chthonic and infernal nature penetrates the virile principle and lowers it to a phallic level. The woman now dominates man as he becomes enslaved to the senses and a mere instrument of procreation. Vis-à-vis the Aphrodistic goddess, the divine male is subjected to the magic of the feminine principle and is reduced to the likes of an earthly demon or a god of the fecundating waters—in other words, to an insufficient and dark power.[23]

(PICTURE: Swedish singer Zarah Leander)

If someone needs the ‘unusual’ to be moved to astonishment, that person has lost the ability to respond rightly to the wondrous, the mirandum, of being. The hunger for the sensational . . . is an unmistakable sign of the loss of the true power of wonder, for a bourgeois-ized humanity.[24]

A society that promotes so much unnatural beauty will no doubt lose the ability to experience the wondrous in the natural. It is essential that people retain the ability to love and be moved by the pure and natural, in order to once again return to a civilization centered in a Traditional Aryan worldview.

Notes

1. Daniel Boyarin, “Sex,” Jewish Women’s Archive.

2. Irene Guenther, Nazi ‘Chic’?: Fashioning Women in the Third Reich (Oxford: Berg, 2004), 50–51.

(Oxford: Berg, 2004), 50–51.

3. Guenther, 16.

4. Guenther, 159.

5. Agnes Gerlach, quoted in Guenther, 146.

6. Guenther, 21–22.

7. Guenther, 26.

8. Matthew Stibbe, “Women and the Nazi state,” History Today, vol. 43, November 1993.

9. Guenther, 93.

10. Stefan Zweig, quoted in Guenther, 9.

11. Jill Stephenson, Women in Nazi Germany (Essex, UK: Pearson, 2001), 88.

(Essex, UK: Pearson, 2001), 88.

12. Stephenson, 133.

13. Guenther, 120.

14. Adolf Hitler, quoted in Guenther, 141.

15. Guenther, 32.

16. Guenther, 100.

17. Guido Knopp, Hitler’s Women (New York: Routledge, 2003), 231.

(New York: Routledge, 2003), 231.

18. Guenther, 99.

19. Guenther, 129.

20. Guenther, 121.

21. Guenther, 111.

22. Gerlach, quoted in Guenther, 145.

23. Evola, Revolt, 223.

24. Josef Pieper, Leisure: The Basis of Culture , trans. Gerald Malsbary (South Bend, Ind.: St. Augustine’s Press, 1998), 102.

, trans. Gerald Malsbary (South Bend, Ind.: St. Augustine’s Press, 1998), 102.