Daniel W. Michaels

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

Editor’s Note:

Since the publication of his review, Viktor Suvorov’s definitive statement of his research has been published as The Chief Culprit: Stalin’s Grand Design to Start World War II [2] (Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 2008).

(Annapolis, Md.: Naval Institute Press, 2008).

French translation here [3]

Viktor Suvorov (Vladimir Rezun)

Poslednyaya Respublika (“The Last Republic”)

Moscow: TKO ACT, 1996

For several years now, a former Soviet military intelligence officer named Vladimir Rezun has provoked heated discussion in Russia for his startling view that Hitler attacked Soviet Russia in June 1941 just as Stalin was preparing to overwhelm Germany and western Europe as part of a well-planned operation to “liberate” all of Europe by bringing it under Communist rule.

Writing under the pen name of Viktor Suvorov, Rezun has developed this thesis in three books. Icebreaker (which has been published in an English-language edition) and Dni M (“M Day”) were reviewed in the Nov.–Dec. 1997 Journal of Historical Review. The third book, reviewed here, is a 470-page work, “The Last Republic: Why the Soviet Union Lost the Second World War,” published in Russian in Moscow in 1996.

Suvorov presents a mass of evidence to show that when Hitler launched his “Operation Barbarossa” attack against Soviet Russia on June 22, 1941, German forces were able to inflict enormous losses against the Soviets precisely because the Red troops were much better prepared for war — but for an aggressive war that was scheduled for early July — not the defensive war forced on them by Hitler’s preemptive strike.

In Icebreaker, Suvorov details the deployment of Soviet forces in June 1941, describing just how Stalin amassed vast numbers of troops and stores of weapons along the European frontier, not to defend the Soviet homeland but in preparation for a westward attack and decisive battles on enemy territory.

Thus, when German forces struck, the bulk of Red ground and air forces were concentrated along the Soviet western borders facing contiguous European countries, especially the German Reich and Romania, in final readiness for an assault on Europe.

In his second book on the origins of the war, “M Day” (for “Mobilization Day”), Suvorov details how, between late 1939 and the summer of 1941, Stalin methodically and systematically built up the best armed, most powerful military force in the world — actually the world’s first superpower — for his planned conquest of Europe. Suvorov explains how Stalin’s drastic conversion of the country’s economy for war actually made war inevitable.

A Global Soviet Union

In “The Last Republic,” Suvorov adds to the evidence presented in his two earlier books to strengthen his argument that Stalin was preparing for an aggressive war, in particular emphasizing the ideological motivation for the Soviet leader’s actions. The title refers to the unlucky country that would be incorporated as the “final republic” into the globe-encompassing “Union of Soviet Socialist Republics,” thereby completing the world proletarian revolution.

As Suvorov explains, this plan was entirely consistent with Marxist-Leninist doctrine, as well as with Lenin’s policies in the earlier years of the Soviet regime. The Russian historian argues convincingly that it was not Leon Trotsky (Bronstein), but rather Stalin, his less flamboyant rival, who was really the faithful disciple of Lenin in promoting world Communist revolution. Trotsky insisted on his doctrine of “permanent revolution,” whereby the young Soviet state would help foment home-grown workers’ uprisings and revolution in the capitalist countries.

Stalin instead wanted the Soviet regime to take advantage of occasional “armistices” in the global struggle to consolidate Red military strength for the right moment when larger and better armed Soviet forces would strike into central and western Europe, adding new Soviet republics as this overwhelming force rolled across the continent. After the successful consolidation and Sovietization of all of Europe, the expanded USSR would be poised to impose Soviet power over the entire globe.

As Suvorov shows, Stalin realized quite well that, given a free choice, the people of the advanced Western countries would never voluntarily choose Communism. It would therefore have to be imposed by force. His bold plan, Stalin further decided, could be realized only through a world war.

A critical piece of evidence in this regard is his speech of August 19, 1939, recently uncovered in Soviet archives (quoted in part in the Nov.–Dec. 1997 Journal, pp. 32–33). In it, Lenin’s heir states:

The experience of the last 20 years has shown that in peacetime the Communist movement is never strong enough to seize power. The dictatorship of such a party will only become possible as the result of a major war . . .

Later on, all the countries who had accepted protection from resurgent Germany would also become our allies. We shall have a wide field to develop the world revolution.

Furthermore, and as Soviet theoreticians had always insisted, Communism could never peacefully coexist over the long run with other socio-political systems. Accordingly, Communist rule inevitably would have to be imposed throughout the world. So integral was this goal of “world revolution” to the nature and development of the “first workers’ state” that it was a cardinal feature of the Soviet agenda even before Hitler and his National Socialist movement came to power in Germany in 1933.

Stalin elected to strike at a time and place of his choosing. To this end, Soviet development of the most advanced offensive weapons systems, primarily tanks, aircraft, and airborne forces, had already begun in the early 1930s. To ensure the success of his bold undertaking, in late 1939 Stalin ordered the build up a powerful war machine that would be superior in quantity and quality to all possible opposing forces. His first secret order for the total military-industrial mobilization of the country was issued in August 1939. A second total mobilization order, this one for military mobilization, would be issued on the day the war was to begin.

Disappointment

The German “Barbarossa” attack shattered Stalin’s well-laid plan to “liberate” all of Europe. In this sense, Suvorov contends, Stalin “lost” the Second World War. The Soviet premier could regard “merely” defeating Germany and conquering eastern and central Europe only as a disappointment.

According to Suvorov, Stalin revealed his disappointment over the war’s outcome in several ways. First, he had Marshal Georgi Zhukov, not himself, the supreme commander, lead the victory parade in 1945. Second, no official May 9 victory parade was even authorized until after Stalin’s death. Third, Stalin never wore any of the medals he was awarded after the end of the Second World War. Fourth, once, in a depressed mood, he expressed to members of his close circle his desire to retire now that the war was over. Fifth, and perhaps most telling, Stalin abandoned work on the long-planned Palace of Soviets.

An Unfinished Monument

The enormous Palace of Soviets, approved by the Soviet government in the early 1930s, was to be 1,250 feet tall, surmounted with a statue of Lenin 300 feet in height — taller than New York’s Empire State Building. It was to be built on the site of the former Cathedral of Christ the Savior. On Stalin’s order, this magnificent symbol of old Russia was blown up in 1931 — an act whereby the nation’s Communist rulers symbolically erased the soul of old Russia to make room for the centerpiece of the world USSR.

All the world’s “socialist republics,” including the “last republic,” would ultimately be represented in the Palace. The main hall of this secular shrine was to be inscribed with the oath that Stalin had delivered in quasi-religious cadences at Lenin’s burial. It included the words: “When he left us, Comrade Lenin bequeathed to us the responsibility to strengthen and expand the Union of Socialist Republics. We vow to you, Comrade Lenin, that we shall honorably carry out this, your sacred commandment.”

However, only the bowl-shaped foundation for this grandiose monument was ever completed, and during the 1990s, after the collapse of the USSR, the Christ the Savior Cathedral was painstakingly rebuilt on the site.

The Official View

For decades the official version of the 1941–1945 German-Soviet conflict, supported by establishment historians in both Russia and the West, has been something like this:

Hitler launched a surprise “Blitzkrieg” attack against the woefully unprepared Soviet Union, fooling its leader, the unsuspecting and trusting Stalin. The German Führer was driven by lust for “living space” and natural resources in the primitive East, and by his long-simmering determination to smash “Jewish Communism” once and for all. In this treacherous attack, which was an important part of Hitler’s mad drive for “world conquest,” the “Nazi” or “fascist” aggressors initially overwhelmed all resistance with their preponderance of modern tanks and aircraft.

This view, which was affirmed by the Allied judges at the postwar Nuremberg Tribunal, is still widely accepted in both Russia and the United States. In Russia today, most of the general public (and not merely those who are nostalgic for the old Soviet regime), accepts this “politically correct” line. For one thing, it “explains” the Soviet Union’s enormous World War II losses in men and materiel.

Doomed from the Start

Contrary to the official view that the Soviet Union was not prepared for war in June 1941, in fact, Suvorov stresses, it was the Germans who were not really prepared. Germany’s hastily drawn up “Operation Barbarossa” plan, which called for a “Blitzkrieg” victory in four or five months by numerically inferior forces advancing in three broad military thrusts, was doomed from the outset.

Moreover, Suvorov goes on to note, Germany lacked the raw materials (including petroleum) essential in sustaining a drawn out war of such dimensions.

Another reason for Germany’s lack of preparedness, Suvorov contends, was that her military leaders seriously under-estimated the performance of Soviet forces in the Winter War against Finland, 1939–40. They fought, it must be stressed, under extremely severe winter conditions — temperatures of minus 40 degrees Celsius and snow depths of several feet — against the well-designed reinforced concrete fortifications and underground facilities of Finland’s “Mannerheim Line.” In spite of that, it is often forgotten, the Red Army did, after all, force the Finns into a humiliating armistice.

It is always a mistake, Suvorov emphasizes, to underestimate your enemy. But Hitler made this critical miscalculation. In 1943, after the tide of war had shifted against Germany, he admitted his mistaken evaluation of Soviet forces two years earlier.

Tank Disparity Compared

To prove that it was Stalin, and not Hitler, who was really prepared for war, Suvorov compares German and Soviet weaponry in mid-1941, especially with respect to the all-important offensive weapons systems — tanks and airborne forces. It is a generally accepted axiom in military science that attacking forces should have a numerical superiority of three to one over the defenders. Yet, as Suvorov explains, when the Germans struck on the morning of June 22, 1941, they attacked with a total of 3,350 tanks, while the Soviet defenders had a total of 24,000 tanks — that is, Stalin had seven times more tanks than Hitler, or 21 times more tanks than would have been considered sufficient for an adequate defense. Moreover, Suvorov stresses, the Soviet tanks were superior in all technical respects, including firepower, range, and armor plating.

As it was, Soviet development of heavy tank production had already begun in the early 1930s. For example, as early as 1933 the Soviets were already turning out in series production, and distributing to their forces, the T-35 model, a 45-ton heavy tank with three cannons, six machine guns, and 30-mm armor plating. By contrast, the Germans began development and production of a comparable 45-ton tank only after the war had begun in mid-1941.

By 1939 the Soviets had already added three heavy tank models to their inventory. Moreover, the Soviets designed their tanks with wider tracks, and to operate with diesel engines (which were less flammable than those using conventional carburetor mix fuels). Furthermore, Soviet tanks were built with both the engine and the drive in the rear, thereby improving general efficiency and operator viewing. German tanks had a less efficient arrangement, with the engine in the rear and the drive in the forward area.

When the conflict began in June 1941, Suvorov shows, Germany had no heavy tanks at all, only 309 medium tanks, and just 2,668 light, inferior tanks. For their part, the Soviets at the outbreak of the war had at their disposal tanks that were not only heavier but of higher quality.

In this regard, Suvorov cites the recollection of German tank general Heinz Guderian, who wrote in his memoir Panzer Leader (1952/1996, p. 143):

In the spring of 1941, Hitler had specifically ordered that a Russian military commission be shown over our tank schools and factories; in this order he had insisted that nothing be concealed from them. The Russian officers in question firmly refused to believe that the Panzer IV was in fact our heaviest tank. They said repeatedly that we must be hiding our newest models from them, and complained that we were not carrying out Hitler’s order to show them everything. The military commission was so insistent on this point that eventually our manufacturers and Ordnance Office officials concluded: “It seems that the Russians must already possess better and heavier tanks than we do.” It was at the end of July 1941 that the T34 tank appeared on the front and the riddle of the new Russian model was solved.

Suvorov cites another revealing fact from Robert Goralski’s World War II Almanac (1982, p. 164). On June 24, 1941 — just two days after the outbreak of the German-Soviet war:

The Russians introduced their giant Klim Voroshilov tanks into action near Raseiniai [Lithuania]. Models weighing 43 and 52 tons surprised the Germans, who found the KVs nearly unstoppable. One of these Russian tanks took 70 direct hits, but none penetrated its armor.

In short, Germany took on the Soviet colossus with tanks that were too light, too few in number, and inferior in performance and fire power. And this disparity continued as the war progressed. In 1942 alone, Soviet factories produced 2,553 heavy tanks, while the Germans produced just 89. Even at the end of the war, the best-quality tank in combat was the Soviet IS (“Iosef Stalin”) model.

Suvorov sarcastically urges establishment military historians to study a book on Soviet tanks by Igor P. Shmelev, published in 1993 by, of all things, the Hobby Book Publishing Company in Moscow. The work of an honest amateur military analyst such as Shmelev, one who is sincerely interested in and loves his hobby and the truth, says Suvorov, is often superior to that of a paid government employee.

Airborne Forces Disparity

Even more lopsided was the Soviet superiority in airborne forces. Before the war, Soviet DB-3f and SB bombers as well as the TB-1 and TB-3 bombers (of which Stalin had about a thousand had been modified to carry airborne troops as well as bomb loads. By mid-1941 the Soviet military had trained hundreds of thousands of paratroopers (Suvorov says almost a million) for the planned attack against Germany and the West. These airborne troops were to be deployed and dropped behind enemy lines in several waves, each wave consisting of five airborne assault corps (VDKs), each corps consisting of 10,419 men, staff and service personnel, an artillery division, and a separate tank battalion (50 tanks). Suvorov lists the commanding officers and home bases of the first two waves or ten corps. The second and third wave corps included troops who spoke French and Spanish.

Because the German attack prevented these highly trained troops from being used as originally planned, Stalin converted them to “guards divisions,” which he used as reserves and “fire brigades” in emergency situations, much as Hitler often deployed Waffen SS forces.

Maps and Phrase Books

In support of his main thesis, Suvorov cites additional data that were not mentioned in his two earlier works on this subject. First, on the eve of the outbreak of the 1941 war Soviet forces had been provided topographical maps only of frontier and European areas; they were not issued maps to defend Soviet territory or cities, because the war was not to be fought in the homeland. The head of the Military Topographic Service at the time, and therefore responsible for military map distribution, Major General M. K. Kudryavtsev, was not punished or even dismissed for failing to provide maps of the homeland, but went on to enjoy a lengthy and successful military career. Likewise, the chief of the General Staff, General Zhukov, was never held responsible for the debacle of the first months of the war. None of the top military commanders could be held accountable, Suvorov points out, because they had all followed Stalin’s orders to the letter.

Second, in early June 1941 the Soviet armed forces began receiving thousands of copies of a Russian-German phrase book, with sections dedicated to such offensive military operations as seizing railroad stations, orienting parachutists, and so forth, and such useful expressions as “Stop transmitting or I’ll shoot.” This phrase book was produced in great numbers by the military printing houses in both Leningrad and Moscow. However, they never reached the troops on the front lines, and are said to have been destroyed in the opening phase of the war.

Aid from the ‘Neutral’ United States

As Suvorov notes, the United States had been supplying Soviet Russia with military hardware since the late 1930s. He cites Antony C. Sutton’s study, National Suicide (Arlington House, 1973), which reports that in 1938 President Roosevelt entered into a secret agreement with the USSR to exchange military information. For American public consumption, though, Roosevelt announced the imposition of a “moral embargo” on Soviet Russia.

In the months prior to America’s formal entry into war (December 1941), Atlantic naval vessels of the ostensibly neutral United States were already at war against German naval forces. (See Mr. Roosevelt’s Navy: The Private War of the U.S. Atlantic Fleet, 1939–1942 by Patrick Abbazia [Annapolis: Naval Institute Press, 1975]). And two days after the “Barbarossa” strike, Roosevelt announced US aid to Soviet Russia in its war for survival against the Axis. Thus, at the outbreak of the “Barbarossa” attack, Hitler wrote in a letter to Mussolini: “At this point it makes no difference whether America officially enters the war or not, it is already supporting our enemies in full measure with mass deliveries of war materials.”

Similarly, Winston Churchill was doing everything in his power during the months prior to June 1941 — when British forces were suffering one military defeat after another — to bring both the United States and the Soviet Union into the war on Britain’s side. In truth, the “Big Three” anti-Hitler coalition (Stalin, Roosevelt, Churchill) was effectively in place even before Germany attacked Russia, and was a major reason why Hitler felt compelled to strike against Soviet Russia, and to declare war on the United States five months later. (See Hitler’s speech of December 11, 1941, published in the Winter 1988–89 Journal, pp. 394–96, 402–12.)

The reasons for Franklin Roosevelt’s support for Stalin are difficult to pin down. President Roosevelt himself once explained to William Bullitt, his first ambassador to Soviet Russia: “I think that if I give him [Stalin] everything I possibly can, and ask nothing from him in return, noblesse oblige, he won’t try to annex anything, and will work with me for a world of peace and democracy.” (Cited in: Robert Nisbet, Roosevelt and Stalin: The Failed Courtship [1989], p. 6.) Perhaps the most accurate (and kindest) explanation for Roosevelt’s attitude is a profound ignorance, self-deception or naiveté. In the considered view of George Kennan, historian and former high-ranking US diplomat, in foreign policy Roosevelt was “a very superficial man, ignorant, dilettantish, with a severely limited intellectual horizon.”

A Desperate Gamble

Suvorov admits to being fascinated with Stalin, calling him “an animal, a wild, bloody monster, but a genius of all times and peoples.” He commanded the greatest military power in the Second World War, the force that more than any other defeated Germany. Especially in the final years of the conflict, he dominated the Allied military alliance. He must have regarded Roosevelt and Churchill contemptuously as useful idiots.

In early 1941 everyone assumed that because Germany was still militarily engaged against Britain in north Africa, in the Mediterranean, and in the Atlantic, Hitler would never permit entanglement in a second front in the East. (Mindful of the disastrous experience of the First World War, he had warned in Mein Kampf of the mortal danger of a two front war.) It was precisely because he was confident that Stalin assumed Hitler would not open a second front, contends Suvorov, that the German leader felt free to launch “Barbarossa.” This attack, insists Suvorov, was an enormous and desperate gamble. But threatened by superior Soviet forces poised to overwhelm Germany and Europe, Hitler had little choice but to launch this preventive strike.

But it was too little, too late. In spite of the advantage of striking first, it was the Soviets who finally prevailed. In the spring of 1945, Red army troops succeeded in raising the red banner over the Reichstag building in Berlin. It was due only to the immense sacrifices of German and other Axis forces that Soviet troops did not similarly succeed in raising the Red flag over Paris, Amsterdam, Copenhagen, Rome, Stockholm, and, perhaps, London.

The Debate Sharpens

In spite of resistance from “establishment” historians (who in Russia are often former Communists), support for Suvorov’s “preventive strike” thesis has been growing both in Russia and in western Europe. Among those who sympathize with Suvorov’s views are younger Russian historians such as Yuri L. Dyakov, Tatyana S. Bushuyeva, and I. V. Pavlova. (See the Nov.–Dec. 1997 Journal, pp. 32–34.)

With regard to 20th-century history, American historians are generally more close-minded than their counterparts in Europe or Russia. But even in the United States there have been a few voices of support for the “preventive war” thesis — which is all the more noteworthy considering that Suvorov’s books on World War II, with the exception of Icebreaker, have not been available in English. (One such voice is that of historian Russell Stolfi, a professor of Modern European History at the Naval Postgraduate School in Monterey, California. See the review of his book Hitler’s Panzers East in the Nov.–Dec. 1995 Journal of Historical Review.) Not all the response to Suvorov’s work has been positive, though. It has also prompted criticism and renewed affirmations of the decades-old orthodox view. Among the most prominent new defenders of the orthodox “line” are historians Gabriel Gorodetsky of Tel Aviv University, and John Ericson of Edinburgh University.

Rejecting all arguments that might justify Germany’s attack, Gorodetsky in particular castigates and ridicules Suvorov’s works, most notably in a book titled, appropriately, “The Icebreaker Myth.” In effect, Gorodetsky (and Ericson) attribute Soviet war losses to the supposed unpreparedness of the Red Army for war. “It is absurd,” Gorodetsky writes, “to claim that Stalin would ever entertain any idea of attacking Germany, as some German historians now like to suggest, in order, by means of a surprise attack, to upset Germany’s planned preventive strike.”

Not surprisingly, Gorodetsky has been praised by Kremlin authorities and Russian military leaders. Germany’s “establishment” similarly embraces the Israeli historian. At German taxpayers expense, he has worked and taught at Germany’s semi-official Military History Research Office (MGFA), which in April 1991 published Gorodetsky’s Zwei Wege nach Moskau (“Two Paths to Moscow”).

In the “Last Republic,” Suvorov responds to Gorodetsky and other critics of his first two books on Second World War history. He is particularly scathing in his criticisms of Gorodetsky’s work, especially “The Icebreaker Myth.”

Some Criticisms

Suvorov writes caustically, sarcastically, and with great bitterness. But if he is essentially correct, as this reviewer believes, he — and we — have a perfect right to be bitter for having been misled and misinformed for decades.

Although Suvorov deserves our gratitude for his important dissection of historical legend, his work is not without defects. For one thing, his praise of the achievements of the Soviet military industrial complex, and the quality of Soviet weaponry and military equipment, is exaggerated, perhaps even panegyric. He fails to acknowledge the Western origins of much of Soviet weaponry and hardware. Soviet engineers developed a knack for successfully modifying, simplifying and, often, improving, Western models and designs. For example, the rugged diesel engine used in Soviet tanks was based on a German BMW aircraft diesel.

One criticism that cannot in fairness be made of Suvorov is a lack of patriotism. Mindful that the first victims of Communism were the Russians, he rightly draws a sharp distinction between the Russian people and the Communist regime that ruled them. He writes not only with the skill of an able historian, but with reverence for the millions of Russians whose lives were wasted in the insane plans of Lenin and Stalin for “world revolution.”

Originally published in the Journal of Historical Review 17, no. 4 (July–August 1998), 30–37. Online source: http://library.flawlesslogic.com/suvorov.htm [4]

See also the National Vanguard review of Icebreaker here [5] and Hitler’s Reichstag speech of December 11, 1941 here [6].

È degno di rilievo il fatto che nel trattato di stabiliva esplicitamente la clausola che ai neri non sarebbe stato concesso il diritto di voto, ad eccezione di quelli residenti nella Colonia del Capo, in cui i coloni inglesi costituivano la maggioranza bianca; perché, nell’Orange e nel Transvaal, i Boeri non avrebbero mai accettato una eventualità del genere, e sia pure in prospettiva futura.

È degno di rilievo il fatto che nel trattato di stabiliva esplicitamente la clausola che ai neri non sarebbe stato concesso il diritto di voto, ad eccezione di quelli residenti nella Colonia del Capo, in cui i coloni inglesi costituivano la maggioranza bianca; perché, nell’Orange e nel Transvaal, i Boeri non avrebbero mai accettato una eventualità del genere, e sia pure in prospettiva futura.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Engagé dans les débats qui déchirent l’éphémère république espagnole (1931-1936), Ortega y Gasset finit par s’en détacher. A titre privé, il penche pour les nationalistes puis préfère quitter l’Espagne. Il n’y revient qu’en 1945, suspect à la fois aux yeux de la dictature franquiste et de l’opposition républicaine.

Engagé dans les débats qui déchirent l’éphémère république espagnole (1931-1936), Ortega y Gasset finit par s’en détacher. A titre privé, il penche pour les nationalistes puis préfère quitter l’Espagne. Il n’y revient qu’en 1945, suspect à la fois aux yeux de la dictature franquiste et de l’opposition républicaine.

Particulièrement impitoyable, la guerre à laquelle fut confronté l’État Indépendant Croate entre 1941 et 1945 s’est achevée, en mai 1945, par l’ignoble massacre de Bleiburg (1). Tueries massives de prisonniers civils et militaires, marches de la mort, camps de concentration (2), tortures, pillages, tout est alors mis en œuvre pour écraser la nation croate et la terroriser durablement. La victoire militaire étant acquise (3), les communistes entreprennent, en effet, d’annihiler le nationalisme croate : pour cela, il leur faut supprimer les gens qui pourraient prendre ou reprendre les armes contre eux, mais aussi éliminer les « éléments socialement dangereux », c’est à dire la bourgeoisie et son élite intellectuelle « réactionnaire ». Pour Tito et les siens, rétablir la Yougoslavie et y installer définitivement le marxisme-léninisme implique d’anéantir tous ceux qui pourraient un jour s’opposer à leurs plans (4). L’Épuration répond à cet impératif : au nom du commode alibi antifasciste, elle a clairement pour objectif de décapiter l’adversaire. Le plus souvent d’ailleurs, on ne punit pas des fautes ou des crimes réels mais on invente toutes sortes de pseudo délits pour se débarrasser de qui l’on veut. Ainsi accuse-t-on, une fois sur deux, les Croates de trahison alors que personne n’ayant jamais (démocratiquement) demandé au peuple croate s’il souhaitait appartenir à la Yougoslavie, rien n’obligeait ce dernier à lui être fidèle ! Parallèlement, on châtie sévèrement ceux qui ont loyalement défendu leur terre natale, la Croatie.

Particulièrement impitoyable, la guerre à laquelle fut confronté l’État Indépendant Croate entre 1941 et 1945 s’est achevée, en mai 1945, par l’ignoble massacre de Bleiburg (1). Tueries massives de prisonniers civils et militaires, marches de la mort, camps de concentration (2), tortures, pillages, tout est alors mis en œuvre pour écraser la nation croate et la terroriser durablement. La victoire militaire étant acquise (3), les communistes entreprennent, en effet, d’annihiler le nationalisme croate : pour cela, il leur faut supprimer les gens qui pourraient prendre ou reprendre les armes contre eux, mais aussi éliminer les « éléments socialement dangereux », c’est à dire la bourgeoisie et son élite intellectuelle « réactionnaire ». Pour Tito et les siens, rétablir la Yougoslavie et y installer définitivement le marxisme-léninisme implique d’anéantir tous ceux qui pourraient un jour s’opposer à leurs plans (4). L’Épuration répond à cet impératif : au nom du commode alibi antifasciste, elle a clairement pour objectif de décapiter l’adversaire. Le plus souvent d’ailleurs, on ne punit pas des fautes ou des crimes réels mais on invente toutes sortes de pseudo délits pour se débarrasser de qui l’on veut. Ainsi accuse-t-on, une fois sur deux, les Croates de trahison alors que personne n’ayant jamais (démocratiquement) demandé au peuple croate s’il souhaitait appartenir à la Yougoslavie, rien n’obligeait ce dernier à lui être fidèle ! Parallèlement, on châtie sévèrement ceux qui ont loyalement défendu leur terre natale, la Croatie.

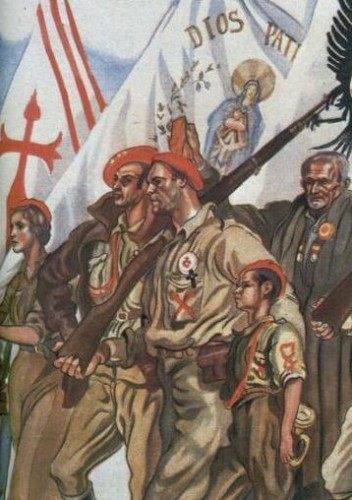

Er zijn echter 4 begrippen die doorheen de geschiedenis van het Carlisme steeds terugkeren en duidelijk op de voorgrond staan: Dios, Patria, Fueros, Rey.

Er zijn echter 4 begrippen die doorheen de geschiedenis van het Carlisme steeds terugkeren en duidelijk op de voorgrond staan: Dios, Patria, Fueros, Rey.

As a historical (rather than a chronological) period, the twentieth century begins in 1914, with the onset of the First World War, whose devastating assault on European existence shook the continent in every one of its foundations, destroying not just its ancien régime, but ushering in what Ernst Nolte calls the “European Civil War” of 1917-45 or what some call the “Thirty Years War” of 1914-45. For amidst its storms of fire and steel, there emerged four rival ideologies — American liberalism, Russian Communism, Italian Fascism, and German National Socialism — each of whose ambition was to reshape the postwar order according to its own scheme for collective salvation. Our world, Venner argues, is a product of these contentious ambitions and of the ideological system — liberalism — that prevailed over its rivals.

As a historical (rather than a chronological) period, the twentieth century begins in 1914, with the onset of the First World War, whose devastating assault on European existence shook the continent in every one of its foundations, destroying not just its ancien régime, but ushering in what Ernst Nolte calls the “European Civil War” of 1917-45 or what some call the “Thirty Years War” of 1914-45. For amidst its storms of fire and steel, there emerged four rival ideologies — American liberalism, Russian Communism, Italian Fascism, and German National Socialism — each of whose ambition was to reshape the postwar order according to its own scheme for collective salvation. Our world, Venner argues, is a product of these contentious ambitions and of the ideological system — liberalism — that prevailed over its rivals.

The clash between aristocratic and democratic values — between Europe and America — reflected, of course, a more profound clash. Venner explains it in terms of Oswald Spengler’s Prussianism and Socialism (1919), which argues that the sixteenth-century Reformation produced two opposed visions of Protestant Christianity — the Calvinism of the English and the Lutheran Pietism of the Germans. The German vision rejected the primacy of wealth, comfort, and happiness, exalting the soldier’s aristocratic spirit and the probity this spirit nurtured in Prussian officialdom. English Protestants, by contrast, privileged wealth (a sign of election) and the external freedoms necessary to its pursuit. This made it a secularizing, individualistic, and above all economic “religion,” with each individual having the right to interpret the Book in his own light and thus to justify whatever it took to succeed.

The clash between aristocratic and democratic values — between Europe and America — reflected, of course, a more profound clash. Venner explains it in terms of Oswald Spengler’s Prussianism and Socialism (1919), which argues that the sixteenth-century Reformation produced two opposed visions of Protestant Christianity — the Calvinism of the English and the Lutheran Pietism of the Germans. The German vision rejected the primacy of wealth, comfort, and happiness, exalting the soldier’s aristocratic spirit and the probity this spirit nurtured in Prussian officialdom. English Protestants, by contrast, privileged wealth (a sign of election) and the external freedoms necessary to its pursuit. This made it a secularizing, individualistic, and above all economic “religion,” with each individual having the right to interpret the Book in his own light and thus to justify whatever it took to succeed.

Vi sono scelte che non vengono perdonate, che fruttano al proprio autore la «damnatio memoriae» perpetua, indipendentemente dal valore del personaggio e da tutto quanto egli possa aver detto o fatto di notevole, prima di compiere, magari per ragioni contingenti e sostanzialmente in buona fede, quella tale scelta infelice.

Vi sono scelte che non vengono perdonate, che fruttano al proprio autore la «damnatio memoriae» perpetua, indipendentemente dal valore del personaggio e da tutto quanto egli possa aver detto o fatto di notevole, prima di compiere, magari per ragioni contingenti e sostanzialmente in buona fede, quella tale scelta infelice.

Nella sua ricerca di un nuovo ordine europeo che consentisse alle «patrie» francese, tedesca, inglese, italiana, di continuare a svolgere un ruolo mondiale nell’era dei colossi imperiali, si era accostato anche a certi ambienti industriali e finanziari che egli definiva «capitalismo intelligente», perché aveva intuito che, in un mondo globalizzato, anche il capitalismo avrebbe potuto svolgere una funzione utile, purché si dissociasse dal nazionalismo e contribuisse a creare migliori condizioni di vita per gli abitanti del Vecchio Continente. Grande utopista, e forse sognatore, Drieu La Rochelle si rendeva però conto della importanza dei fattori materiali della vita moderna, e intendeva inserirli nel quadro della nuova Europa da costruire.

Nella sua ricerca di un nuovo ordine europeo che consentisse alle «patrie» francese, tedesca, inglese, italiana, di continuare a svolgere un ruolo mondiale nell’era dei colossi imperiali, si era accostato anche a certi ambienti industriali e finanziari che egli definiva «capitalismo intelligente», perché aveva intuito che, in un mondo globalizzato, anche il capitalismo avrebbe potuto svolgere una funzione utile, purché si dissociasse dal nazionalismo e contribuisse a creare migliori condizioni di vita per gli abitanti del Vecchio Continente. Grande utopista, e forse sognatore, Drieu La Rochelle si rendeva però conto della importanza dei fattori materiali della vita moderna, e intendeva inserirli nel quadro della nuova Europa da costruire.

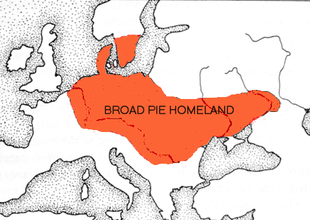

Los primeros hombres, con ojos de color de cielo y cabellos de color de luz, engastaron en sus dagas de sílex la Piedra de Luna… pusieron en movimiento las aspas del sol y se adueñaron de la Tierra por añadidura. Buscaban Avalón en este mundo y la Piedra de Luna tuvo para ellos significado diferente. El Guía fue el primer Caminante de la Aurora y su nombre cambia en las Edades. La Piedra de Luna estuvo entre sus cejas. La daga de sílex en sus manos. La Tierra bajo sus plantas. La piel del Carnero fue el emblema que se mecía al viento de esas edades.

Los primeros hombres, con ojos de color de cielo y cabellos de color de luz, engastaron en sus dagas de sílex la Piedra de Luna… pusieron en movimiento las aspas del sol y se adueñaron de la Tierra por añadidura. Buscaban Avalón en este mundo y la Piedra de Luna tuvo para ellos significado diferente. El Guía fue el primer Caminante de la Aurora y su nombre cambia en las Edades. La Piedra de Luna estuvo entre sus cejas. La daga de sílex en sus manos. La Tierra bajo sus plantas. La piel del Carnero fue el emblema que se mecía al viento de esas edades.

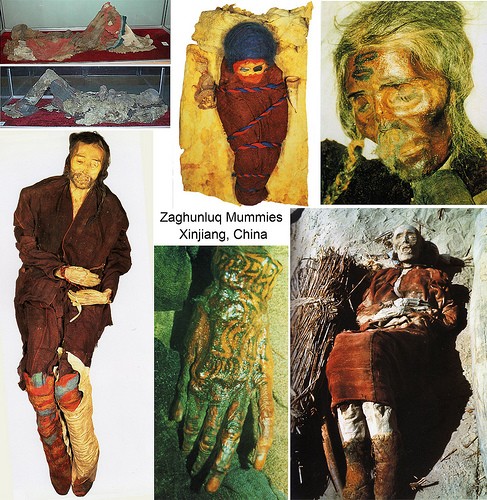

Eu estava, pois, apoiado no bar, bebericando um xarope de romã, quando vi avançar na minha direção um homenzinho calvo com alguns fios longos ao redor das orelhas; visivelmente ele tinha vontade de debater, pouco importando o assunto; nós bebemos e ele falou; ou o contrário; ele tinha um velho sobretudo negro, cujas manchas eram muito grandes, óculos que eram verdadeiros binóculos e se exprimia com um sotaque curioso, que enrolava os “r”, vindo talvez de qualquer parte do leste. Uma mistura de professor Girassol com Bergier. Ele me contou uma história engraçada sobre múmias que foram descobertas na China em um deserto, múmias de “gigantes loiros”, dizia. Ele desapareceu no momento em que eu pagava a conta; eu me perguntei se ele não era uma aparição, de um ou de outro dos personagens anteriormente citados; sim, eu sei que o professor Girassol não existe que sob o lápis de Hergé, mas sabe-se lá. Paul-Georges Sansonetti deve saber. Eu havia esquecido esta história até os dias de hoje, quando eu fiz algumas pesquisas. Somente para saber que o homenzinho não brincava.

Eu estava, pois, apoiado no bar, bebericando um xarope de romã, quando vi avançar na minha direção um homenzinho calvo com alguns fios longos ao redor das orelhas; visivelmente ele tinha vontade de debater, pouco importando o assunto; nós bebemos e ele falou; ou o contrário; ele tinha um velho sobretudo negro, cujas manchas eram muito grandes, óculos que eram verdadeiros binóculos e se exprimia com um sotaque curioso, que enrolava os “r”, vindo talvez de qualquer parte do leste. Uma mistura de professor Girassol com Bergier. Ele me contou uma história engraçada sobre múmias que foram descobertas na China em um deserto, múmias de “gigantes loiros”, dizia. Ele desapareceu no momento em que eu pagava a conta; eu me perguntei se ele não era uma aparição, de um ou de outro dos personagens anteriormente citados; sim, eu sei que o professor Girassol não existe que sob o lápis de Hergé, mas sabe-se lá. Paul-Georges Sansonetti deve saber. Eu havia esquecido esta história até os dias de hoje, quando eu fiz algumas pesquisas. Somente para saber que o homenzinho não brincava. É o turcólogo alemão F.W. K. Muller quem deu, em 1907, o nome de tokariana a uma língua que nós podemos decifrar facilmente nos manuscritos, pois eles estavam anotados de maneira bilíngüe tokariano – sânscrito. Os lingüistas teriam em seguida estabelecido os vínculos entre esta língua e as línguas indo-européias, essencialmente o celta e o germânico. Nós reencontraremos alguma sonoridade similar nestes exemplos, respectivamente em português², francês, latim, irlandês e tokariano: mãe, mère, mater, mathir, macer. Irmão, frère, frater, brathir, prócer (próximo do inglês “brother”), três, trois, tres, tri, tre (segundo Giovanni Monastra).

É o turcólogo alemão F.W. K. Muller quem deu, em 1907, o nome de tokariana a uma língua que nós podemos decifrar facilmente nos manuscritos, pois eles estavam anotados de maneira bilíngüe tokariano – sânscrito. Os lingüistas teriam em seguida estabelecido os vínculos entre esta língua e as línguas indo-européias, essencialmente o celta e o germânico. Nós reencontraremos alguma sonoridade similar nestes exemplos, respectivamente em português², francês, latim, irlandês e tokariano: mãe, mère, mater, mathir, macer. Irmão, frère, frater, brathir, prócer (próximo do inglês “brother”), três, trois, tres, tri, tre (segundo Giovanni Monastra).  Cette année 2011 marque le 70e anniversaire de la naissance de l’État Indépendant Croate, un épisode majeur de l’histoire de la Croatie au XXe siècle mais aussi un événement qui soulève encore d’âpres controverses. Le 10 avril 1941 fut-il un accident de l’histoire, fut-il au contraire une étape logique et inéluctable de la vie nationale croate ou encore une simple péripétie orchestrée par Hitler et Mussolini pour servir leurs intérêts ? Extrêmement délicat eu égard aux méchantes polémiques que suscitent encore les faits et gestes des Croates durant la IIe Guerre mondiale, le débat n’est toujours pas clos et il n’est peut-être pas inutile de faire le point.

Cette année 2011 marque le 70e anniversaire de la naissance de l’État Indépendant Croate, un épisode majeur de l’histoire de la Croatie au XXe siècle mais aussi un événement qui soulève encore d’âpres controverses. Le 10 avril 1941 fut-il un accident de l’histoire, fut-il au contraire une étape logique et inéluctable de la vie nationale croate ou encore une simple péripétie orchestrée par Hitler et Mussolini pour servir leurs intérêts ? Extrêmement délicat eu égard aux méchantes polémiques que suscitent encore les faits et gestes des Croates durant la IIe Guerre mondiale, le débat n’est toujours pas clos et il n’est peut-être pas inutile de faire le point.