Thomas Sheehan

Making Sense of Heidegger: A Paradigm Shift [2]

New York: Rowman & Littlefield, 2014

Making sense of Heidegger just got a whole lot easier.

Making sense of Heidegger just got a whole lot easier.

When I was in graduate school, Aristotle and Heidegger were the two philosophers I studied most thorougly. Heidegger is a notoriously difficult writer, so naturally I sought out secondary literature for guidance. Unfortunately, most Heidegger literature is not particularly helpful. The best guides to Heidegger I discovered were Otto Pöggeler [3], Graeme Nicholson [4], Michael Zimmerman [5], Richard Polt [6], and Thomas Sheehan [7] — especially Sheehan.

Sheehan’s work was particularly important for me, because he pays special attention to Heidegger’s debts to Aristotle and Husserl, debts which cannot be overestimated but are usually given short shrift. I found Sheehan’s writing to be so penetrating, while at the same time clear and engaging, that I went on to read practically everything he wrote, for instance his books Karl Rahner: The Philosophical Foundations [8] and The First Coming: How the Kingdom of God Became Christianity [9], which I never would have read for the subject matter alone.

Two of Sheehan’s articles were particularly fateful for my subsequent intellectual development, for he was the first person I ever read who mentioned Julius Evola [10] and Alain de Benoist, [11] although my ultimate reactions were certainly not what he was aiming for.

Once I was out of graduate school, however, I stopped following the secondary literature on Heidegger, even the really good stuff. By then, I could read Heidegger on my own, without training wheels. And since I was a mere “amateur” Heideggerian, I had no professional credentials to maintain.

Of course I continued to follow new releases of Heidegger’s own writings. And I admit to picking up a few pieces of secondary literature: Polt’s The Emergency of Being [12], Charles Bambach’s Heidegger’s Roots: Nietzsche, National Socialism, and the Greeks [13] , Julian Young’s Heidegger’s Later Philosophy [14], and, just for the fun of it, Adam Sharr’s Heidegger’s Hut [15]. But I was pretty much on the wagon until November, when I decided to review Alexander Dugin’s dreadful book [16] on Heidegger.

, Julian Young’s Heidegger’s Later Philosophy [14], and, just for the fun of it, Adam Sharr’s Heidegger’s Hut [15]. But I was pretty much on the wagon until November, when I decided to review Alexander Dugin’s dreadful book [16] on Heidegger.

Fortunately, when I bought Dugin, Amazon suggested I might also like Thomas Sheehan’s Making Sense of Heidegger. Never have I clicked a “buy” button more quickly. The book arrived as soon as it was published, actually on the day I finished reading Dugin. But still, it felt late, decades late. I wish Sheehan had published this book 25 years ago.

A Paradigm Shift

Making Sense of Heidegger argues for a “paradigm shift” in Heidegger interpretation: from Being to meaning, and from meaning to the source of meaning. According to Sheehan, Heidegger’s ultimate concern is with the question: what makes meaning possible? What makes it possible for beings to be meaningfully present to a knower? (For Heidegger, a scientific account of how the sense organs and the brain operate is not an adequate answer to this question, because science presupposes the meaningful presence of eyeballs, gray matter, etc.)

Sheehan makes a crushingly convincing case for his thesis, marshaling quotes from the nearly 100 volumes of Heidegger’s published writings, analyzing Heidegger’s basic terminology, establishing equivalencies among his terms, establishing equivalencies between Heideggerese and more intelligible idioms, re-translating and paraphrasing difficult texts in light of his analysis, and laying it all out step-by-step, with summaries and repetitions along the way, so you never lose the thread of the argument.

As you will see from some of the quotes below, Sheehan’s prose can be dense, bristling with hyphenated phrases, neologisms and unfamiliar terms, and words and phrases in German, Latin, and untransliterated ancient Greek. It is a lot more forbidding and thorny than it needs to be, which artificially limits the audience and impact of Sheehan’s argument to professional scholars and educated, dedicated amateurs. One wishes that Sheehan’s editors had forced him through one more draft with an eye to making this book intelligible to bright undergraduate students, which would have been possible for a writer of his proven skill. But still, the book is clear “in itself” and, unlike most literature on Heidegger, actually worth the effort. Heidegger is yet to find his Alan Watts, but whoever he may be will have to read this book.

Sheehan’s book has 10 chapters in three parts plus an Introduction and a Conclusion, occupying 294 pages altogether, plus three short appendices, a long and detailed bibliography of Heidegger’s writings in German and English translations, a briefer biography of other works cited, and two indexes: one of German, English, and Latin terms, the other of ancient Greek terms.

Sheehan’s Thesis

Sheehan states his basic thesis in his Foreword and Introduction (chapter 1) entitled “Getting to the Topic.”

Heidegger is famously interested in “Being” (Sein). Yet Sheehan argues that Heidegger’s concept of Being has been systematically misunderstood by most Heidegger scholars. In the philosophical tradition, talk of Being refers to objective, mind-independent reality, indeed “ultimate” reality — such as God, or atoms in void, or an underlying mental or material “stuff” — that gives rise to the beings we perceive around us.

For Heidegger, however, “Being” refers to the meaningful presence of beings to a knower. Heidegger makes this understanding quite explicit in “The End of Philosophy and the Task of Thinking” where he glosses “the Being of beings” as “the presence of that which is present.”[1] Present to whom? Heidegger calls the one to whom beings show up Dasein. (In ordinary German, “Dasein” means existence. Heidegger treats it as a compound of Da [there] and Sein [Being], hence “the place of Being,” i.e., the one to whom beings are present.)

Heidegger does not question the existence of mind-independent objects, although he was certainly skeptical of accounts of “ultimate” mind-independent realities. But for Heidegger, Being is ultimately involved with the human knower. Indeed, it always has been. One of the most remarkable features of Heidegger’s interpretations of Parmenides, Heraclitus, Plato, and Aristotle are his arguments that even their accounts of Being are implicitly cast in relation to the human knower.

For Heidegger, then, Being = the meaningful presence of beings to man. Thus ontology (the branch of metaphysics that deals with Being) is equivalent to phenomenology, which studies the disclosure of beings to man.

But this is just the beginning of Sheehan’s paradigm shift, for Heidegger’s ultimate concern is not Being (understood phenomenologically) but something beyond Being [17]. In Being and Time, Heidegger calls this the “sense” (Sinn) of Being (hence the title Making Sense of Heidegger). Heidegger has many other names for this something “beyond” Being: the temporality (Zeitlichkeit) of Dasein, the truth (Wahrheit) of Being, the essence (Wesen) of Being, Being itself or Being as such (das Sein selbst), the manifestness (Offenbarkeit) of Being, the clearing (Lichtung) of Being, the event of appropriation (Ereignis), etc.

For Sheehan, all of these names point to the same topic: the source of meaningful presence, what which opens up the “space” in which beings are meaningfully present to a knower. “The single issue that drove Heidegger’s work was not being-as-meaningful-presence but rather the source or origin of such meaningful presence” (p. xv).

In Sheehan’s terms, this source is the “thrownness” (Geworfenheit) or “thrown openness” (der geworfener Entwurf) of Dasein, to use the language of Being and Time. Or it is the “clearing” (Lichtung) or “appropriated clearing” (die ereignete Lichtung) of the later Heidegger. But both vocabularies refer to the same thing: the a priori (always-already-operative) conditions that make possible meaningful presence to a knower. “The always-already-operative thrown-open clearing is the ‘thing itself’ of all Heidegger’s work” (p. 21). So I do not wear out the hyphen key on my computer, I am just going to boil this all down to one word: the clearing.

Before we go any further, I need to define the clearing (Lichtung) and another key term of Heideggerese: appropriation (Ereignis).

The Clearing

In ordinary German, Lichtung means “clearing,” like a clearing in the forest. The verb lichten means to clear land. Lichtung is related to Licht (light), because a clearing allows light to reach the forest floor and illuminate whatever enters the clearing. (“Light from above” is the literal meaning of “epiphany.” The clearing allows light from above.) Heidegger uses the metaphor of the clearing to refer to the conditions allow beings to be meaningfully present to a knower. The clearing is the “space” in which beings become present.

We can see and hear physical objects in physical space. We can see and hear them, because there is a space between us which our senses can traverse. Physically, light and sound come to us, but from the first person point of view, our eyes and ears reach out for experience.

Just as we see and hear things in physical space, Heidegger believes that things have meaning in a “space” as well. Because Heidegger is talking about meaning, not seeing, this use of clearing exploits another sense of lichten: to weigh anchor, to lighten a load, to free up. In this sense, Lichtung is a free and open space: the space in which beings can be meaningfully encountered.

Each object has meaning within a larger network or “world” of meanings supplied by language, culture, and tradition. Worlds of meaning are collective. In hermeneutics, such contexts of meaning are called “horizons,” for just as the horizon is the boundary of the visible world, horizons are the context in which things have meaning. But what opens up these horizons, these worlds of meaning?

Each object has meaning within a larger network or “world” of meanings supplied by language, culture, and tradition. Worlds of meaning are collective. In hermeneutics, such contexts of meaning are called “horizons,” for just as the horizon is the boundary of the visible world, horizons are the context in which things have meaning. But what opens up these horizons, these worlds of meaning?

In Being and Time, Heidegger speaks of man as Dasein, the place (da) of meaning (Sein), and man is opened up as the space of meaning by “temporality” (Zeitlichkeit), the temporal structure of our consciousness of meaning. This is the sense in which for Heidegger “time” is the “horizon” of “Being” (meaning). In his later writings, summarized in the 1962 lecture “Time and Being,” Heidegger offers new terms. Instead of Being, he speaks of (meaningful) presence (Anwesenheit). Instead of time as the horizon of Being, he speaks simply of the clearing in which beings become meaningfully present.

For Heidegger, the clearing is intrinsically hidden. As Sheehan puts it, quoting Heidegger at the end:

As the ultimate presupposition, the clearing must always be presupposed in any attempt to know it. It always lies “behind” us, so to speak, and it will always remain behind us (i.e., unknowable) even when we turn around to take a look at it. Consequently, we cannot go “beyond” or “behind” it without contradicting ourselves. We cannot (without moving in a vicious circle) seek the presupposition of this ultimate presupposition of all our seeking. “There is nothing else to which appropriation could be led back or in terms of which it could be explained.” (p. 227)

Heidegger’s term of the intrinsic hiddenness of the clearing is Seinsvergessenheit (forgottenness of Being), although what is forgotten is not Being but the clearing, and it has not been forgotten because it has been hidden and overlooked throughout the history of Western philosophy.

Appropriation

For Heidegger, Ereignis refers to the intimate and reciprocal relationship of man and meaning: meaning cannot exist without man, and man cannot exist without meaning.

In ordinary German, Ereignis means “event.” However, from its first appearance as a technical term in Heidegger’s lectures in 1919, it means more than an event. Contrary to Sheehan, who insists Ereignis does not mean an event at all, Heidegger introduces the term in the context of talking about processes of consciousness and “lived experience” (Erlebnis, which he hyphenates as Er-lebnis to intensify the sense of process). For Heidegger, Ereignis is the name of a more intimate connection between knower and known than Er-lebnis. To emphasize this intimacy, this mutual belonging between knower and known, Heidegger introduces a hyphen (Er-eignis), turning it — against all etymology — into a compound term meaning “to make one’s own,” to take possession. Heidegger later approved the French appropriement (appropriation, as in taking possession) as a translation of Ereignis. For Heidegger, the appropriation of man and meaning is mutual and reciprocal: we belong to one another.

The sense in which Ereignis also means “event” has to do with what Heidegger calls Seinsgeschichte, which is his account of the emergence of different worlds of meaning (such as the modern world, which is defined by the presupposition that all beings are transparent to consciousness and available for manipulation). Heidegger claims, in his late essay “Time and Being,” that these ages simply happen, one after another, and since these ages set the outward boundaries of intelligibility, we cannot get behind their succession to understand their why and wherefore. Meaning happens. Worlds of meaning happen. We can make sense of things within these worlds of meaning. But we cannot make sense of meaning itself. What gives meaning is hidden behind its gift.

These collective worlds of meaning are created and sustained by man, but they are not created by human consciousness. (There is more to man than consciousness. Even within the mind, consciousness is just the tip of the iceberg.) For Heidegger, language, culture, and traditions create human consciousness; human consciousness does not create language, culture, and tradition. Human consciousness and creativity take place only within a space opened by language, culture, and tradition.

Heidegger does not deny that Shakespeare wrote plays, Handel wrote oratorios, and Klee painted pictures. But he would deny that their creations are entirely individual and entirely products of the conscious mind. If they were, they would be contrived and probably unintelligible. Human creativity is situated in existing worlds of meaning and traditions of practice, and it carries these forward. Humans are not disembodied consciousnesses who can create ex nihilo.

Thus when it comes to explaining deep historical transformations, Heidegger does not think that philosophers, poets, or other “hidden legislators” hatch ideas and plans and propagate them to the rest of the culture. Rather, he claims that such individuals are merely the first ones to become conscious of and articulate stirrings in the Zeitgeist.

This would seem obscurantist, were it not for the fact that it does capture our experience of being shaped and enthralled by collective worlds of meaning before we even attain self-consciousness. It would seem disempowering, if it did not imply that dissenting ideas, too, are not merely the subjective dreams of marginal individuals but rather our awareness of historical forces far greater than ourselves. Perhaps dissent occurs to us only when change is already underway.

Part One: Aristotelian Beginnings

In What is Called Thinking? Heidegger recommends that his students spend ten or fifteen years studying Aristotle before they pick up Nietzsche. The same advice could apply to Heidegger himself. Thus Part One of Sheehan’s book is called Aristotelian Beginnings, encompassing chapter 2, “Being in Aristotle,” and chapter 3, “Heidegger Beyond Aristotle.” These chapters focus on Aristotle, but they also pay sufficient attention to Heidegger’s readings of Plato and the pre-Socratics to constitute a good introduction to Heidegger’s interpretation of ancient philosophy.

The chapter on “Being in Aristotle” deals with Heidegger’s reading of Aristotle as a proto-phenomenological thinker whose account of Being implicitly defines Being in relationship to the human knower: “. . . ousia [Being] is the intelligible appearance or meaningful presence (aletheia [truth] and parousia [presence]) of things in logos, and thus that ousia is the openness or availability of things to human beings” (p. 25). When Heidegger read Aristotle in light of Husserl’s account of “categorial intuition” in the Sixth Logical Investigation, Heidegger was able to focus on the phenomenon of intelligible presence (as opposed to mere sense experience), which then led him to his own distinct question: what is the source of intelligible presence? This is the topic of chapter 3.

These chapters are a tour de force. They brought me back to my graduate seminars in Aristotle and rekindled my first feelings of astonishment at Aristotle’s genius. Although this section is quite thorough and illuminating, at 76 pages, it becomes a bit of a slog. Sheehan himself suggests that some readers might be tempted to skip to the second section, on Being and Time, and read the Aristotle chapters later. I followed his advice, and I am glad I did. I think that he should have followed his own advice and made this the third and final section of the book.

Yes, one understands Being and Time better with a background in Aristotle, but that does not mean that we need to read about Heidegger’s interpretation of Aristotle first. All of us read Being and Time first anyway. And we all had questions that were later clarified by understanding Heidegger’s debts to Aristotle, Husserl, etc. Sheehan’s order of exposition could have followed that path of discovery, and his book would have much more accessible for it.

A New Level of Inquiry?

At the beginning of chapter 3, Sheehan argues that there are three levels to Heidegger’s topic. According to Sheehan, Heidegger’s ultimate topic is: (1) not Being (meaning), (2) not the meaning of Being (the meaning of meaning = the clearing), but (3) the meaning of the meaning of Being (the meaning of the meaning of meaning = the clearing of the clearing). In Sheehan’s words:

Heidegger’s question turns out to be

1. not “Whence beings?” — the answer to that is: being; 2. nor even “Whence being at all?” — the answer to that is: the open clearing; 3. but rather “Whence and how is there ‘the open’?” or equally “Whence and how is there the clearing?” (p. 69)

This is news to me.

Sheehan offers the following quote from Heidegger in support of this:

When the being-question is understood and posed in this way, one must have already gone beyond being itself. Being and another now come into language. This “other” must then be that wherein being has its emergence and its openness (clearing — disclosing) — in fact, wherein openness itself has its own emergence. (p. 69)

For Heidegger, the clearing is the ultimate condition of meaning. It is what makes everything else intelligible. And that means that it itself is not intelligible, meaning that we cannot place it in a wider context, i.e., a clearing of its own. If we could put it in a clearing of its own, then it would not, by that very fact, be the ultimate condition of meaning. This leaves us with two options.

- First, one can accept that the clearing is unintelligible. Heidegger arrived at this conviction in 1930 in his lecture “On the Essence of Truth,” in which he argued that the ultimate context of meaning cannot be made meaningful. As Sheehan puts it, “the clearing is intrinsically ‘hidden’: always present-and-operative but unknowable in its why and wherefore” (p. 116).

- Second, one can claim that the clearing makes itself intelligible. And that is what Heidegger seems to be doing in the passage above: the “‘other’ . . . wherein being has its emergence and its openness (clearing — disclosing)” is our clearing. Then he claims that the clearing is “in fact, wherein openness itself [the clearing] has its own emergence.”

Of course, if the clearing is entirely unintelligible, then everything Heidegger says about it is nonsense. It frequently seems that way, but it is not. This implies that something like the second position is true: we “encounter” the clearing “in” the clearing, and although we cannot “get behind” it to make “ultimate” sense of it, we can still say a lot about it. For one thing, we can talk about the functions it performs. For another thing, we can understand why we cannot understand it.

Sheehan interprets the quote from Heidegger as follows:

We note here again the two elements of Heidegger’s own question (1) the move “beyond being” to its “whence” — namely, the clearing; and (2) the move “beyond the clearing” to its “whence” — namely Ereignis as the appropriation of ex-sistence. (p. 69)

I do not, however, think that Ereignis is “beyond the clearing” so much as it is a description from “within” the clearing of how the clearing operates, namely the clearing simply happens, and we can’t get behind it to understand why it happens or what is causing it. Ereignis is another term for the basic inscrutability of the clearing.

Part Two: The Early Heidegger

Part Two is divided into three chapters: chapter 4, “Phenomenology and the Formulation of the Question”; chapter 5, “Ex-sistence as Openness”; and chapter 6, “Becoming Our Openness.”

The first chapter is a very accessible and engaging account of Heidegger’s basic phenomenological approach to ontology: We are immersed in a world of meaning. The world is always-already meaningful, before we even try to make sense of it. For Heidegger, this world of meaning, this meaningful presence of beings to us (Dasein), is Being. Heidegger’s overriding question is: what makes meaningful presence (Being) possible? What opens man up, allowing the meaningful presence of beings?

The second chapter deals with this question in terms of Being and Time, which aimed “to show that and how meaningful presence — ‘being in general’ — is made possible by and occurs only within human openedness as the clearing” (p. 134).

Man’s Openedness

Heidegger distinguishes between individual instances of openedness, which he calls Dasein, and the structure of human openedness itself, which he calls Existenz and Da-sein (although he is not always consistent about using the hyphen). Sheehan renders the latter two terms as “ex-sistence,” from the Latin ex + sistere, to be forced to stand ahead or beyond. This forced aspect is captured by “openedness” as opposed to mere “openness.”

Heidegger distinguishes between individual instances of openedness, which he calls Dasein, and the structure of human openedness itself, which he calls Existenz and Da-sein (although he is not always consistent about using the hyphen). Sheehan renders the latter two terms as “ex-sistence,” from the Latin ex + sistere, to be forced to stand ahead or beyond. This forced aspect is captured by “openedness” as opposed to mere “openness.”

On pp. 136-37, Sheehan points out an interesting quote from a posthumously published collection of 1941-42 notes,[2] where Heidegger claims that the “da” in Dasein should not be translated as here, there, here/here, etc. (Which of course would include my preferred rendition “place.”) Instead, Heidegger claims that the “da” is not locative at all, but refers to the “openedness” of human ex-sistence. Of course, I do not think that anyone who translated the “da” as here, there, etc. thinks it refers to a literal place, any more than the clearing is a literal clearing.

Sheehan gives a series of very interesting quotes from Heidegger on the “da”:

[The “da”] should designate the openedness where things can be present for human beings, and human beings for themselves.

. . . being human, as such, is distinguished by the fact that to be, in its own unique way, is to be this openedness.

The human being occurs in such a way that he or she is the “Da,” that is, the clearing of being. (p. 137)

The Da refers to that clearing in which things stand as a whole, in such a way that, in this Da, the being of open things shows itself and at the same time withdraws. To be this Da is a determination of man.

[Ex-sistence] is itself the clearing.

The clearing: the Da – is itself ex-sistence.

The point is to experience Da-sein in the sense that human being itself is the Da, that is, the openedness of being, in that a person undertakes to preserve it, and in preserving it, to unfold it (See Sein und Zeit, p. 132f. [= 170f.]).

Ex-sistence must be understood as being-the-clearing. Da is specifically the word for the open expanse.

Ex-sistence [das Da-sein] is the way in which the open, the clearing, occurs, within which being as cleared is opened up to human understanding.

To be — the clearing — to be cast into the clearing as the open = to-be-the-Da. (p. 138)

Human ex-sistence means that man is not defined by what he is at present, what is simply there, what is simply actual, what shows up to an outside observer as a being occupying a delimited space at the present time. When we view human ex-sistence from the inside, we realize that to be human means to be forced outside the present, the actual, and into the future, the possible. This compulsion is what Heidegger means by “thrownness.”

This thrownness outside the present and the actual is what makes man “open” to meaning. Humans ex-sist by projecting ahead of themselves a range of possibilities, a range of concrete potential ways of being. These possibilities are given to us by our past. They are also finite: we do not have all possibilities, and the possibilities that we do have cannot be simultaneously realized.

It is only in light of these possibilities that we “return” to what is present and actual and render it meaningfully present. For instance, if look across the prairie and see an oncoming storm, I am “ahead of myself” in appraising what might happen, and in light of those possibilities, what is present shows up to me in terms of its serviceability for shelter or escape.

This temporal structure in which the past creates possibilities in terms of which we render things (past and present) as meaningfully present is the temporality (Zeitlichkeit) of Da-sein, which for Heidegger is the “horizon” of Being (meaning), i.e., that which opens man up, that which creates the space in which meaningful presence is possible. This temporal structure of being thrown into future possibilities and returning to render things meaningfully present is also the structure of logos. In Being and Time, Heidegger equates “the temporality [Zeitlichkeit] of discourse [Rede = logos]” with that of “Dasein [ex-sistence] as such” (quoted on p. 150).

Heidegger describes human ex-sistence by saying that “possibility is higher than actuality” and that human existence is a matter of “excess.” Both of these claims point to the fact that human existence exceeds what is given and actual (to the outside observer). We exceed the actual and present into a realm of future possibilities.

On page 136, Sheehan makes a couple of dubious inferences from these claims.

First, that the priority of possibility over actuality is incompatible with a classical ethics of self-actualization, as if Plato and Aristotle did not recognize that each man has many possibilities besides the actualization of his nature in accordance with virtue; as if Aristotle believed, for example, that one can only hit the mean rather than stray into excess or defect.

Second, he claims that the idea of human ex-sistence being in “excess” of human actuality overturns the Greek idea of moderation (nothing in excess), as if the very notion of temperance did not imply the possibility of excess and defect in the pursuit of pleasure, and as if the very existence of human potentiality refutes the pursuit of virtue when in fact it is what makes it possible and necessary. Heidegger’s “excess” is the space in which virtue, as well as the vices of excess and defect, become possible.

Becoming Who We Are

The third chapter of Part Two, “Becoming Our Openness,” does extraordinary work in illuminating some of Being and Time’s most alluring yet elusive and obscure ideas, namely its existential and practical (but, as well shall see, not moral) dimension, which is encapsulated in the injunctions of the 17th-century German mystic Angelus Silesius, “Human being, become what you essentially are!” and of Pindar, “Become what you already are!”

Now, as a follower of the Platonic or Aristotelian idea of an ethics of self-actualization, I would interpret what we “already” or “essentially” are as our daimon, our ideal self, which exists in potency and whose actualization is the well-being (eudaimonia) we all seek.

For Heidegger, what we already are is not a single determinate potentiality, but a whole range of possibilities — possibilities that could include self-actualization but also self-betrayal, virtue as well as vice, good as well as evil. Thus the choice Heidegger is discussing is not the moral choice between good and evil, but the existential choice between embracing or rejecting our freedom. And for Heidegger, our freedom means a whole range of possibilities, not just the good ones.

But in what sense are we even faced with such a choice? Long before we are mature enough to reflect upon who we really are, people have been telling us who we are. These external spectators (the crowd) look upon us as actual, present beings and ascribe traits to us: jock, bimbo, nerd, preacher’s kid, etc. Because we don’t know better, we actually come to internalize these traits. But what are the chances that these descriptions actually fit, that they really capture who we are?

But before we can become who we really are — and as an Aristotelian, I think that is meaningful and possible — we need to embrace our freedom, meaning our whole range of possibilities, including the inevitability of our death and the possibility that we might die at any time, which gives a certain urgency to our mission.

“They” tell us that who we are. But when we look within, we discover that we are thrown ahead into a range of future possibilities. We are not what we are (right now), i.e., actuality. Rather, we are what we are not (yet), i.e., possibility. We are free either to accept the fact of our freedom, which is what Heidegger calls authenticity, or to flee it into inauthenticity, which basically boils down to shrugging off the burden of freedom and letting others determine our identity for us.

But what makes our freedom, such as it is, possible? Heidegger’s answer would have to be: the things that determine us, which for him come down to our heritage: our language, culture, traditions, historical epoch, and the like. I would add our genetic heritage as well — our race, our sex, our individual traits — although that is a topic for another time. All of these give us certain possibilities, while making other things impossible. For example, being a prince or a peasant make certain things possible, other things impossible

And since it is in light of these possibilities that what is given becomes meaningfully present, our openedness as a whole is historically conditioned and particularized.

And if authenticity means embracing rather than fleeing our freedom, that is equivalent to embracing rather than fleeing from the heritage that determines us as well as frees us.

Heidegger talks about authentic Dasein “becoming its fate,” but he might as well have said amor fati, for one can come to love our limits when one appreciates that they are the conditions of our freedom.

Heidegger’s own discussion of our relationship to our past is primarily in terms of making our heritage meaningfully present in light of future possibilities, and retrieving/carrying forward certain elements. However, it strikes me that a deeper relationship with our past is implied by authenticity: not picking and choosing elements of our heritage that show up to us within our openedness, but embracing heritage as a condition of openedness — which, as an ultimate condition of intelligibility, remains obscure to us.

The affirmation of a form of historical identity so deeply constitutive of our self and self-consciousness that it can never be objectified, much less criticized or discarded, would place Heidegger in the tradition of anti-rationalist conservatism of David Hume and Edmund Burke. Sheehan — whose own Left-wing, progressivist agenda becomes more apparent as the book goes on — emphasizes the transcendental rather than the historical elements of Heidegger’s account of openedness, and freedom rather than the boundaries that make it possible.

Part Three: The Later Heidegger

Part Three is divided into three chapters: chapter 7, “Transition: From Being and Time to the Hidden Clearing”; chapter 8, “Appropriation and the Turn”; and chapter 9, “The History of Being.” The first two chapters can be discussed as a unit, because they deal with the same topic: Heidegger’s concept of the “turn” (Kehre) which in its primary sense is identical to his concept of Ereignis.

One of Sheehan’s most important accomplishments is his clarification of the multiple sense of Heidegger’s “turn.” The “turn” is usually thought of as a shift in Heidegger’s thinking, either within Being and Time or between Being and Time and Heidegger’s later thought. Sheehan argues, however, that the fundamental sense of the turn is identical to Ereignis, i.e., it refers to the mutual dependence of man and meaning: meaning cannot exist without man, and man cannot exist without meaning.

The unity of man and meaning can, however, be viewed under different aspects: from the side of man or from the side of meaning. Being and Time was originally planned to have two divisions, each divided into three parts. In 1927, Heidegger published only parts 1 and 2 of division one. Part 3 was not published, and the manuscript was either lost or destroyed. Division two was never begun.

In Being and Time, parts 1 and 2, Heidegger approaches the man/meaning unity from the man side, using the phenomenological method to describe the temporal structure of ex-sistence which opens the space of meaningful presence. In the unpublished part 3, Heidegger was to approach the same unity from the side of meaning. Instead of showing how man opens up the space of meaning, he was to show how the space of meaning claims man. As Heidegger put it, the first parts of Being and Time deal with “human being in relation to the clearing” while part 3 deals with “the clearing and its openness in relation to human being” (quoted in Sheehan, p. 244).

This shift in perspective is often misinterpreted as the turn in Heidegger’s thought. But it is intimately related to the primary sense of the turn: the unity of man/meaning, which allows us to look at it from either side.

Heidegger never published Being and Time, division one, part 3. Sheehan does an important service by gathering all the testimonies about the lost text to reconstruct its outline and contents, to speculate about its teaching, and to explain why it was never published.

In the 1930s, Heidegger’s approach to his abiding topic — what makes meaningful presence possible — shifted from transcendental phenomenology to what he called Seinsgeschichte, which explores the different dispensations of Being/worlds of meaning in Western (and now world) history. This shift is also misinterpreted as the turn in Heidegger’s thought.

However, this turn, like the other, is made possible by the primary sense of the turn. Indeed, the turn within Being and Time and the turn from Being and Time to the late Heidegger are attempts to execute the same shift of perspective: from a transcendental/human-side approach to a meaning-sided approach to the man/meaning unity. Why did the first turn fail, and why did the second take a historical form?

The first turn failed because every discourse requires a context. A phenomenology of human ex-sistence provided the context for the first parts of Being and Time, but when Heidegger set aside the transcendental phenomenological method and the human-centered standpoint, he needed another context, another standpoint, from which to explore the man/meaning relationship from the side of meaning. But he lacked this context at the time he was writing Being and Time.

In 1930, Heidegger came to the realization, discussed above, that if the clearing is the ultimate condition of meaning, it itself remains unintelligible. But, although one cannot get beyond the clearing, perhaps one can say something about it from inside. But how? The outline of Being and Time, division two — which was to be a dismantling of Western ontology, moving from Kant to Descartes to Aristotle — certainly provided a clue.

For Heidegger, meaning embodied in language, culture, and tradition constitutes human consciousness, not vice-versa. But to say more about how history shapes human consciousness, one would have to compare different historical epochs. Heidegger is not, however, interested in ordinary intellectual and cultural history, but in the succession of fundamental interpretive slants — the a priori, i.e., hidden and always-already-operative assumptions about the nature of man and world — that cut through and unify entire cultures and ages. This brings us to Sheehan’s next chapter, “The History of Being,” to which I will attend in due course.

Inflating the Human

Heidegger’s belief that socially embodied meaning constructs individual consciousness — i.e., that consciousness is not “behind” history but history is “behind” consciousness — is the substance of his “anti-humanism.” “Anti-humanism” is something of a misnomer, though, since history and culture are just as “human” as individual consciousness. Heidegger is really opposed to the subject-centered transcendental method and the idea that the individual creates his own world of meaning, as opposed to receiving and passing on collective meanings to which he might contribute some small improvements.[3] The transcendental method also goes hand-in-hand with a dismissal of transcendent metaphysics. Sheehan writes:

The paradox of Being and Time as published is that the finitude of ex-sistence guarantees the infinitude of ex-sistence’s reach. Our structural engagement with meaning is radically open-ended and in principle without closure. Yes, there is an intrinsic limit to that stretch: ex-sistence can encounter the meaning only of material things, for as embodied and thrown, ex-sistence is “submitted” exclusively to sensible things rather than being open to trans-sensible (“meta-physical”) reality. But that notwithstanding, the search for the meanings of spatio-temporal things meets no barrier inscribed “thus far and no farther,” because we can always ask “Why no farther? What am I being excluded from?” and thus transcend the barrier, if only interrogatively. And secondly, yes, ex-sistence is thoroughly mortal and will certainly die, and its death will mark the definitive end to its search for meaning. But although it will surely end, perhaps even tragically, ex-sistence will nonetheless go out with its glory intact, insofar as it will die as an in-principle unbounded capacity for the meaning of everything it can sensibly encounter. (p. 192)

First, it strikes me as vacuous to say that we can make sense of everything by stipulating that one of those “senses” includes awareness that we have not made sense of something. Second, if this notion of the Faustian infinitude of ex-sistence’s reach is an accurate description of Being and Time, parts 1 and 2, it strikes me as precisely the kind of human-centric teaching that was to be modified by the turns in Heidegger’s thinking within Being and Time, and from Being and Time to the later Heidegger.

Indeed, as Sheehan continues to set forth this Faustian interpretation of Heidegger, it looks suspiciously like what Heidegger came to call the “essence” of technology, i.e., the a priori assumption that all beings are in principle knowable and disposable by man:

Structurally and in principle we are able to know everything about everything, even though we never will. Such ever-unrealized omniscience comes with our very ex-sistence. (Husserl: “God is the ‘infinitely distant man.’”) This open-ended possibility is a “bad infinity,” which in this context denotes the asymptosis of endless progress in knowledge and control. Heidegger’s philosophical critique of (as contrasted with his personal opinions about) the modern age of science and technology cannot, on principle be leveled against our ability to endlessly understand the meaning of things and even to bring them under our control, because this possibility is given with human nature, as Aristotle intimated and as Heidegger accepts in principle. What troubles Heidegger, rather, is the generalized overlooking of one’s mortal thrown-openness in today’s Western, and increasingly global, world. The mystery of human being consists in both the endless comprehensibility of whatever we can meet and the incomprehensibility of why everything is comprehensible. Everything is knowable — except the reason why everything is knowable. (p. 193)

The claim that we are able to “know everything about everything” strikes me as every bit as dogmatic as any claim of transcendent metaphysics. (Even if we knew everything about a particular subject, could we ever know that we knew everything?) And since when is “knowing” everything equivalent to “understanding the meaning” of everything, i.e., interpreting everything? Surely this kind of talk — which every academic knows can go on forever — is not necessarily equivalent to endless progress in knowledge.

Sheehan makes it quite clear that he thinks this Faustian viewpoint is not just “early Heidegger” but “late Heidegger” too. He also gives the strong impression that he thinks it is true:

. . . once Heidegger has established this argument about man’s a priori projectedness, he can and must affirm the obvious: that within the limits of our thrownness, we ourselves do indeed decide the meanings of things on our own initiative, whether practically or theoretically. . . . Yes, we are structurally thrown-open; but nonetheless it is we ourselves, as existentiel actors, who decide the current whatness and howness of things, their jeweiliges Sein. What is more, there is in principle no limit to what we can know about the knowable or do with the doable. There should be no shrinking back from the human will, no looking askance at the scientific and technological achievements of existentiel “subjects” in the modern world . . . Underlying the whole of Heidegger’s philosophy is the fact that we cannot encounter anything outside the parameters that define us as human — as a thrown-open, socially and historically embodied logos. But granted that much, we also cannot not make sense of anything we meet, whether in practice or in theory. . . . Heideggerians seem a bit anxious about the practical (not to mention technological) achievements of the existentiel subject — including socio-political projects for “changing the world.” However, as to zoon logon to echon [living beings possessing reason] we possess the power not only to make sense of things cognitively but also to remake the world as we see fit, for better or worse. But we possess that power only because we are possessed by the existential ability to make sense and change the world . . . (pp. 208–9)

This sense of being “possessed” by the ability to know and do anything captures the enthralling quality of every dispensation of Being, including the a priori assumption of technological civilization, which Heidegger calls Gestell or Ge-Stell. (Gestell is another untranslatable bit of Heideggerese which means the a priori assumption that for man everything is transparent and available. This is the “essence” of technology, meaning the prevailing mode of disclosing beings that makes modern technological civilization possible.)

But whereas Sheehan thinks we should be celebrating this worldview, Heidegger sought to awaken us from it, to break the spell. How? By showing us that the idea that everything can be understood and controlled is itself an Ereignis, a dispensation of meaning that we cannot understand or control. And if we can’t know why everything is knowable, isn’t that a refutation of the idea that everything is knowable?

Sheehan himself says: “Everything is knowable — except the reason why everything is knowable,” although he does not draw the conclusion Heidegger would like. If we cannot know why we think we can know everything, then we cannot know everything. Simply put, Heidegger is offering a counter-example to the idea we can know and control everything, and a single counter-example is sufficient to refute a universal generalization.

Heidegger’s counter-example is not, moreover, just a single instance that could be partitioned off as an exception to the rule, for what dispenses modernity is ultimately the whole of Western — and now global — civilization, understood as a realm of embodied meaning. We stand at the center of a circle — or better, a sphere — of meanings shading off into mysteries in all directions, and each time we bring a new mystery into the light, we understand that it is a gift from that which remains concealed.

Deflating the Trans-Human

Sheehan’s tendency to inflate the human (the subject-centered) is matched with a tendency to deflate the trans-human, historical dimensions of Heidegger’s thought. This is particularly evident in his discussion of Ereignis. In keeping with his program of breaking us out of both the egocentrism of the phenomenological method and the vaulting ambitions of the Gestell, Heidegger speaks of Ereignis and the clearing almost as if they have wills of their own. Sheehan, however, dismisses this as merely “reifying” language that:

. . . presents Ereignis or Sein selbst or Seyn as if it were a quasi-something that “catches sight” of human being, calls it into its presence, and makes it its own, as in such unfortunate sentences as . . . . “Er-eignen originally means: to bring something into view, that is, to catch sight of it, to call it into view, to ap-propriate it.” The “something” that is allegedly “brought into view” is ex-sistence; and this hypostatizing language makes it seem that something separate from ex-sistence “sees” ex-sistence and makes it its own property. . . . The danger that constantly lurks in Heidegger’s rich and suggestive lexicon is that his technical terms will take on a life of their own as words and then get substituted for what they are trying to indicate, the way some scholarship treats the clearing (or das Sein selbst) “as if it were something present ‘over against’ us as an object.” Thus Heidegger’s key term Ereignis – especially when English scholarship leaves it in the German — risks becoming a reified thing in its own right, a supra-human Cosmic Something that enters into relations with ex-sistence, dominates it, and sends Sein to it while withholding itself in a preternatural realm of mystery. To avoid such traps and to appreciate what Heidegger means by Ereignis, we must always remember that the term bespeaks our thrown-openness as the groundless no-thing of being-in-the-world, which we can experience in dread or wonder. Above all we should apply Heidegger’s strict phenomenological rule to appropriation itself: “avoid any ways of characterizing it that do not arise out of the personal claims it makes on you.” (pp. 234–35)

But Heidegger’s language does not suggest a false opposition between human ex-sistence and the clearing (which are just two different ways of viewing the same thing). Instead, Heidegger is trying to articulate a real opposition between the individual ego and socially-embodied meaning. Heidegger is trying to communicate that meaning is not created by the individual ego, but instead the individual ego is created by socially-embodied meaning. When individuals reflect upon language, culture, and history, we experience them as things that existed before our consciousness emerged, as things that will continue to exist after our consciousness has ended, and as external forces that envelop and enthrall us. They do stand over against us as objects — and also behind us as conditions of our subjectivity. Ereignis is not a “supra-human Cosmic Something” but a supra-individual Cultural-Linguistic-Historical Something. This something does enter into a relation with each individual Dasein. It does dominate us. It does send worlds of meaning to us while withholding itself in a realm of mystery, a mystery that is not “preternatural” but historical and thus “preterindividual.” This is not, in short, the “reification” of ideas but simply good, honest phenomenology: characterizing the experience of appropriation/the clearing as it actually occurs to us.

There is no question that Heidegger’s writing is highly rhetorical, with a penchant for mystical, religious, and prophetic forms of expression. The desire to get through the rhetoric to what Heidegger is really saying is completely understandable and commendable, and Sheehan has done more than any scholar I know to get to Heidegger’s real message. But once one arrives at this understanding, one cannot merely give Heidegger’s rhetoric the brush-off, like an annoyingly chatty cab driver once he has gotten you to your destination. One has to turn back to the rhetoric and try to understand why Heidegger adopted it in the first place.

One also needs to understand the contents of Heidegger’s teachings to separate the purely psychological dimensions of this thought. Heidegger was clearly an odd duck. He writes repeatedly about aberrant mental states in the 1920s and ‘30s, and in 1945–’46 he suffered a nervous breakdown. Heidegger’s biographers can provide many more psychological details. But before a competent psychiatrist tries to make sense of Heidegger’s psyche, he should read Sheehan to make sense of his thought.

The History of Being

Sheehan’s chapter 9, “The History of Being” and Conclusion, chapter 10, “Critical Reflections,” can be discussed as a unit, because they deal with the same essential subject matter. (Chapter 10 focuses on Heidegger’s essay “The Question Concerning Technology,” which discusses the Gestell, which is the present dispensation in the history of Being.) As usual, Sheehan marshals a host of useful quotations, etymologies, and distinctions.

These chapters deal with Heidegger at his most anti-humanist, anti-modernist, and ultra-conservative. And, as you might already suspect, Sheehan is quite unsympathetic. At one point. Sheehan summarizes what he thinks is of enduring value in Heidegger:

. . . a phenomenological rereading of traditional being as the meaningfulness of things; a persuasive explanation of how we make sense of things, both in praxis and in apophantic discourse; the grounding of all sense-making in the a priori structure of human being as a mortal dynamism of aheadness-and-return; and, based on all of that, a strong philosophical exhortation, in the tradition of Greek philosophical protreptic, to become what we already are and to live our lives accordingly. (p. 267)

This is basically Being and Time, plus a couple of lectures, “What is Metaphysics?” and “On the Essence of Truth,” with a cut-off around the end of 1930.

Heidegger interprets the trajectory of Western — and now global — history as one of decline from classical Greek and Roman civilization to the present day. Heidegger traces this decline in terms of the history of metaphysics, but contra Sheehan, Heidegger does not believe that philosophers are the “hidden legislators” of mankind, i.e., that philosophical ideas are the foundation of culture and the driving force of history. Rather, in keeping with his anti-humanism, Heidegger holds that historical change arises from inscrutable sources, and philosophers, as well as poets like Sophocles and Hölderlin, merely receive and articulate the deepest currents of the Zeitgeist.

As articulated by the pre-Socratics and the Attic tragedians, Heidegger thinks the deepest a priori assumptions of the classical view of the world are that man is a mortal being inhabiting a splendid world bounded by mystery and necessity, boundaries that man cannot transgress in thought or deed without hubris that courts nemesis. The deepest a priori assumptions of modernity are that all boundaries of thought and action, including human mortality itself, are ultimately temporary, i.e., that everything is in principle knowable and controllable by man.

Heidegger’s distinction between the classical and the modern corresponds roughly to Spengler’s distinction between classical and Faustian civilizations, although Heidegger places both within a single historical narrative of decline, whereas Spengler regards them as separate civilizational organisms each of which has undergone its own phase of decline, with the decline of the West still occurring today.

Sheehan points out that Heidegger names only two dispensations in the history of Being, both of them modern: the age of the world picture (the a priori assumptions of early modernity) and the Gestell (the a priori assumptions of present-day global technological civilization).

Sheehan dismisses Heidegger’s claim that the decline of the West is caused by man’s deepening oblivion of the clearing. But setting aside the question of causation, it is actually an accurate description of the decline, for oblivion of the clearing is equivalent to oblivion of human finitude, of the dependence of the individual on collective embodied meaning, and of the ineluctable mystery of the ultimate source of meaning — and all of these are traits of the Gestell. Forgetting the clearing is forgetting one’s place, metaphysically speaking. To the Greeks, this is hubris. Technology, surely, can exist without hubris. But could modernity?

Sheehan presents a wonderful quilt quotation from Heidegger’s 1935 lecture course Introduction to Metaphysics illustrating Heidegger’s conservative lament at the civilizational consequences of modernity:

. . . the hopeless frenzy of unchained technology and the rootless organization of the average man . . . spiritual decline . . . the darkening of the world, the flight of the gods . . . the destruction of the earth, the reduction of human beings to a mass, the preeminence of the mediocre . . . the disempowering of spirit, its dissolution, diminution, suppression, and misinterpretation . . . all things sinking to the same depths, to a flat surface resembling a dark mirror that no longer reflects anything and gives nothing back . . . the boundless etcetera of the indifferent, the ever-the-same . . . the onslaught of what aggressively destroys all rank, every world-creating impulse of the spirit . . . the regulation and mastery of the material relations of production . . . the instrumentalization and misinterpretation of spirit. (p. 282)

In this same lecture course, Heidegger famously declared that the “inner truth and greatness of National Socialism” was its potential to reverse these tendencies, to preserve human rootedness, distinct identities, and traditional social structures from the deracinating and leveling forces of “global technology.” Sheehan suggests that Heidegger added this comment when he edited the lectures for publication in 1953, but if so, it is consistent with the rest of the lectures, as indicated by Sheehan’s own quilt quotation. (National Socialism falls outside the purview of Sheehan’s book, but he makes sure we know he’s against it.)

Sheehan is also dismissive of Heidegger’s postwar thoughts on the way out of the modern dispensation, particularly in his 1949 lecture “The Turn,” which is obscure even for Heidegger. The lecture also adds to the confusion about Heidegger’s concept of the turn by introducing a new sense of Kehre. This “turn” refers to the advent of the next dispensation of Being, in which mankind awakens “from oblivion of Being, to oblivion of Being.” Here Being refers to the clearing. Oblivion of Being refers to the intrinsic hiddenness of the clearing as well as to our lack of awareness of the intrinsic hiddenness of the clearing. Our awakening, therefore, refers to becoming aware of the intrinsic hiddenness of the clearing, which is equivalent to awakening to the fact that we cannot understand and control the dispensations of Being, which should overthrow the hubristic assumption that we can understand and control everything.

Sheehan again laments the “perverse rhetoric of hypostatization and reification that Heidegger employs, as if Being Itself, after centuries of ‘refusing Itself’ to humankind, suddenly chooses to turn and show Itself” (p. 265). But again, this is Heidegger’s description of how historical change presents itself to him. If the human will cannot control history, but history changes anyway, then history would seem to have a will of its own.

If we cannot control history, then what is the meaning of dissent? If ideas do not shape history, does that imply that dissenting ideas are merely subjective, private, and ineffectual? Not necessarily. Heidegger would have to hold that dissenting ideas are themselves dispensations of Being. If they are out of step with the present dispensation, perhaps they are the first glimmers of a new one. It is not surprising, therefore, that Heidegger occasionally adopts the tone of a prophet. If you find it annoying, just remember that it is far less pretentious than the idea that philosophers are the architects of history.

Heidegger is just one prophet of this new dispensation. It first stirred in 18th-century critics of the Enlightenment like Vico, Rousseau, and Herder. In the 19th century, it was taken up by such movements as Romanticism, Transcendentalism, utopian socialism, the pre-Raphaelites, and Arts and Crafts, as well as various Symbolists, Decadents, and dandies. In the 20th century, it stirred the prophets of deep ecology, agrarianism, and natural living like Aldo Leopold, Savitri Devi, J. R. R. Tolkien, E. F. Schumacher, Wendell Berry, and Carlo Petrini. It overlaps significantly with neo-paganism, Traditionalism, and Western seekers of Eastern wisdom, as well as with mystical and traditional forms of Christianity. It is also at work in the ongoing resistance to globalization, which, according to sociologists Charles Lindholm and José Pedro Zúquete, embraces the European New Right as well as movements of the Left.[4]

We should also remember that the man/meaning relationship is one of mutual dependency. Yes, collective meanings have the advantage in relation to any individual. But meaning depends upon man just as man depends upon meaning. The present dispensation may have claimed and shaped us, but it still needs us to sustain it. That means that each individual faces choices that sustain or undermine the present dispensation.

We sustain it whenever we participate in the global technological system, whenever we demand things that are faster, cheaper, easier, and more available. We undermine it whenever we prefer the local to the global, the beautiful over the useful, the earthy over the plastic, distinct peoples over monoculture and miscegenation, the acceptance of reality over the striving for power, the unique over the mass-produced, the ecosystem over the economic system, etc. Heidegger is just one face in a giant Sgt. Pepper’s collage of anti-modernists, along with generations of Wandervogel and hippies, historical preservationists and organic gardeners, Identitarians and Zapatistas, monkeywrenchers and tree-spikers, druids and swamis, down to flannel-clad hipsters tending bees and brewing beer in Brooklyn. When enough of us live as if the new dispensation is already here, perhaps it will arrive.

Sheehan complains that Heidegger’s account of the a priori assumptions of modernity is not based on fine-grained historical analysis. I guess it seems insufficiently inductive to him. (Yes, the oil industry seems in the grip of world-dominating hubris. But what about the coal industry?) But this seems to miss the point. We will not encounter the a priori assumptions of modernity in front of us, for they are already behind us, within us, structuring how we see the world and ourselves. Since we are all more or less modern men, we can test the truth of Heidegger’s claims simply through self-reflection.

Sheehan dates himself a bit by complaining that the 96 volumes of Heidegger’s Complete Edition published to date make no mention of Kapitalismus — as if Heidegger’s analysis of modernity needed recourse to Marxist buzzwords, as if he had not transcended the opposition of capitalism and socialism and revealed their underlying metaphysical identity.

* * *

Although I am nonplussed by Sheehan’s criticisms of Heidegger, I have some of my own. I am skeptical of his post-Kantian transcendental quarantine of metaphysics. I am skeptical of his biological race-denial and would like to explore his rationale. I am not so sure that the clearing is intrinsically hidden at all, or hidden in a non-trivial way.

But my main objection to Heidegger is his terrible writing. I long ago lost count of the Heideggerian words that actually don’t mean what they seem to mean. Heidegger translator David Farrell Krell recounts, “Occasionally, I would bring [Heidegger] a text of his that simply would not reveal his meaning; he would read it over several times, grimace, shake his head slightly, and say, ‘Das ist aber schlecht!’ (That is really bad!).”[5] I wish I could get back every hour I wasted reading Derrida and Foucault. I don’t feel the same way about Heidegger. But especially with certain works, I feel like those South African miners who have to sift through mountains of rubble for a pocketful of gems. When it comes to making sense of Heidegger, the philosopher was his own worst enemy, which makes Thomas Sheehan’s scholarly career a work of friendship. Making Sense of Heidegger is an indispensable book on an unavoidable thinker.[6]

Notes

1. Martin Heidegger, “The End of Philosophy and the Task of Thinking,” translated by Joan Stambaugh, in On Time and Being, trans. Joan Stambaugh (New York: Harper & Row, 1972), p. 62 and Basic Writings, revised and expanded, ed. David Farrell Krell (New York: HarperCollins, 1993), p. 438.

2. Martin Heidegger, Das Ereignis, ed. Friedrich Wilhelm von Herrmann, Gesamtausgabe, vol. 71 (Frankfurt a.M.: Klostermann, 2009). In English: The Event, trans. Richard Rojcewicz (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2013).

3. Even a Shakespeare’s contributions to the English language are small compared to what he inherited.

4. Charles Lindholm and José Pedro Zúquete, The Struggle for the World: Liberation Movements for the 21st Century (Stanford, Stanford University Press, 2010).

5. David Farrell Krell, “Work Sessions with Martin Heidegger,” Philosophy Today 26 (1982), p. 138.

6. As a book, Making Sense of Heidegger is not particularly attractive, but it is well-edited. I spotted only a few mistakes: p. ix: GA 6 should be Nietzsche, vols. 1 and 2; p. 210: “breaks” should be “brakes”; p. 262: “synchronic” and “diachronic” are reversed.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Sin embargo, la convivencia entre buenos propósitos y acciones deshonestas por parte de los gobernantes fue siempre una de las características de Roma. Un ejemplo de esto fue Licinio Calvo Estolón, tribuno de la plebe en el 377 a.C., que introdujo una fuerte limitación a la acumulación de tierras por parte de un único propietario, además de una severa reglamentación para los deudores, pero luego fue acusado de haber violado sus propias leyes.

Sin embargo, la convivencia entre buenos propósitos y acciones deshonestas por parte de los gobernantes fue siempre una de las características de Roma. Un ejemplo de esto fue Licinio Calvo Estolón, tribuno de la plebe en el 377 a.C., que introdujo una fuerte limitación a la acumulación de tierras por parte de un único propietario, además de una severa reglamentación para los deudores, pero luego fue acusado de haber violado sus propias leyes. Otras leyes importantes fuero la «Lex Sempronia» (122 a.C.) o la «Lex Servilia de Repetundis» (111 a.C.), que establecieron penas más severas para los delitos de cohecho. La segunda, en concreto, fue la primera ley que introdujo la pérdida de los derechos políticos. Ambas fueron completadas con otras como la «Lex Livia Iudiciaria» (91 a.C.), que impuso una corte especial para los juicios contra los jueces corruptos que hubieran cometido extorsión, o la «Lex Cornelia», que aumentaba las condenas para los magistrados que aceptaran dinero en un juicio por cohecho. Esta última debe su nombre al dictador Lucio Cornelio Sila, que la estableció tres años antes de morir.

Otras leyes importantes fuero la «Lex Sempronia» (122 a.C.) o la «Lex Servilia de Repetundis» (111 a.C.), que establecieron penas más severas para los delitos de cohecho. La segunda, en concreto, fue la primera ley que introdujo la pérdida de los derechos políticos. Ambas fueron completadas con otras como la «Lex Livia Iudiciaria» (91 a.C.), que impuso una corte especial para los juicios contra los jueces corruptos que hubieran cometido extorsión, o la «Lex Cornelia», que aumentaba las condenas para los magistrados que aceptaran dinero en un juicio por cohecho. Esta última debe su nombre al dictador Lucio Cornelio Sila, que la estableció tres años antes de morir.

Quoi qu’il en soit, Houellebecq a le vent en poupe et l’on peut gager qu’il pulvérisera les ventes de début d’année. Il ne s’inscrit pas moins à la suite d’auteurs précurseurs comme Jean Raspail, lui-même empruntant, avec son prophétique et magistral Camp des saints, la dimension proprement visionnaire d’un Jules Verne au XIXe siècle ou d’un Anthony Burgess avec son Orange mécanique au XXe siècle.

Quoi qu’il en soit, Houellebecq a le vent en poupe et l’on peut gager qu’il pulvérisera les ventes de début d’année. Il ne s’inscrit pas moins à la suite d’auteurs précurseurs comme Jean Raspail, lui-même empruntant, avec son prophétique et magistral Camp des saints, la dimension proprement visionnaire d’un Jules Verne au XIXe siècle ou d’un Anthony Burgess avec son Orange mécanique au XXe siècle.

Paul Gottfried recently retired as Professor of Humanities at Elizabethtown College, PA. He is the author of

Paul Gottfried recently retired as Professor of Humanities at Elizabethtown College, PA. He is the author of

J’ai écrit La Grande Séparation parce que je suis affolé de la perte de notre mémoire historique qui accompagne la perte de notre identité nationale. Le monde dans lequel nous vivons encore est dessiné par des frontières, par des nations, qui nous donnent notre citoyenneté et notre identité. Le principe de la souveraineté nationale garantit aux citoyens la liberté de décider de leurs lois, de leurs mœurs, de leur destin, sur leur territoire et à l’intérieur de leurs frontières. Les conditions d’acquisition de la citoyenneté assurent l’unité de la nation, et la transmission entre les générations. La séparation est géographique, respectueuse des cultures, des civilisations, de la diversité collective des peuples.

J’ai écrit La Grande Séparation parce que je suis affolé de la perte de notre mémoire historique qui accompagne la perte de notre identité nationale. Le monde dans lequel nous vivons encore est dessiné par des frontières, par des nations, qui nous donnent notre citoyenneté et notre identité. Le principe de la souveraineté nationale garantit aux citoyens la liberté de décider de leurs lois, de leurs mœurs, de leur destin, sur leur territoire et à l’intérieur de leurs frontières. Les conditions d’acquisition de la citoyenneté assurent l’unité de la nation, et la transmission entre les générations. La séparation est géographique, respectueuse des cultures, des civilisations, de la diversité collective des peuples.

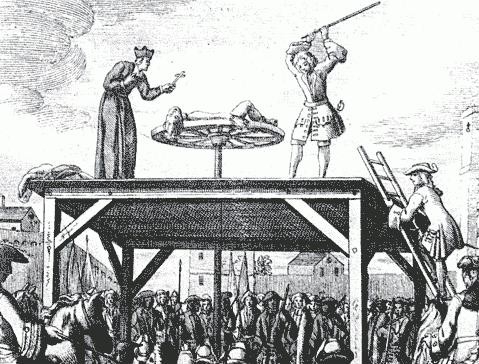

Il faut bien avouer que les tâches allouées aux bourreaux ne sont pas d’ordre à lui attirer toutes les sympathies. En plus d’exécuter les condamnés par des peines jugées parfois comme infamantes, il est d’usage qu’il chasse des rues mendiants, lépreux et animaux errants. Il touche une taxe sur la prostitution. C’est lui qui nettoie la place du marché une fois celui-ci terminé. Il dispose de plus du droit de havage sur toutes les marchandises entrant dans la ville, c'est-à-dire qu’il prélève une certaine quantité de denrées à chaque marchand venant vendre au marché, ce qui est très mal accepté par ceux-ci en vertu de l’impureté supposée de l’exécuteur. Le bourreau se bat continuellement contre les préjugés et les violences éventuelles dont il peut être l’objet de la part de la population et il a, comme les nobles, le droit de porter l’épée (plus pour se protéger que par honneur…). Certaines personnes passent outre cette marginalité pour aller se faire soigner chez les bourreaux qui, en complément de leur activité, pratiquent la médecine ou la chirurgie, forts de leur connaissance du corps humain. Les cadavres des condamnés leur servent parfois de complément de revenus : ils les revendent aux chirurgiens (pratique longtemps interdite par l’Eglise), en prélèvent la graisse pour la revendre à ceux qui veulent soigner leurs varices…

Il faut bien avouer que les tâches allouées aux bourreaux ne sont pas d’ordre à lui attirer toutes les sympathies. En plus d’exécuter les condamnés par des peines jugées parfois comme infamantes, il est d’usage qu’il chasse des rues mendiants, lépreux et animaux errants. Il touche une taxe sur la prostitution. C’est lui qui nettoie la place du marché une fois celui-ci terminé. Il dispose de plus du droit de havage sur toutes les marchandises entrant dans la ville, c'est-à-dire qu’il prélève une certaine quantité de denrées à chaque marchand venant vendre au marché, ce qui est très mal accepté par ceux-ci en vertu de l’impureté supposée de l’exécuteur. Le bourreau se bat continuellement contre les préjugés et les violences éventuelles dont il peut être l’objet de la part de la population et il a, comme les nobles, le droit de porter l’épée (plus pour se protéger que par honneur…). Certaines personnes passent outre cette marginalité pour aller se faire soigner chez les bourreaux qui, en complément de leur activité, pratiquent la médecine ou la chirurgie, forts de leur connaissance du corps humain. Les cadavres des condamnés leur servent parfois de complément de revenus : ils les revendent aux chirurgiens (pratique longtemps interdite par l’Eglise), en prélèvent la graisse pour la revendre à ceux qui veulent soigner leurs varices… Les grands changements continuent avec la Révolution. La loi du 13 juin 1793 adoptée par la Convention impose un bourreau par département. Celui-ci recevra un salaire fixe et ne pourra plus prétendre à ses anciens droits féodaux, abolis. Le fait le plus notable est que le bourreau est désormais considéré comme un citoyen comme les autres, ce qui a tendance à faire reculer son statut de paria aux yeux de la population. En 1790, l’Assemblée Nationale décrète l’abolition de la torture, de l’exposition des corps ainsi que l’égalité des supplices, ce qui a comme conséquence de modifier en profondeur les activités des exécuteurs. Ceux-ci utilisent dès 1792 un mode d’exécution unique : la guillotine. Alors que la France est attaquée à ses frontières et que la Révolution se radicalise, le bourreau et sa machine deviennent peu à peu très populaires, ils sont les grands symboles de la libération du peuple et de l’épuration de la société. Le bourreau, qui désormais se salit bien moins les mains avec le nouveau mode d’exécution, devient le « vengeur du peuple » et sa machine à décapiter le « glaive de la liberté ». Il faut dire que la guillotine fonctionne entre 1792 et 1794 à plein régime. A la différence des procédés anciens, elle permet des exécutions continues voire industrielles. Le célèbre bourreau de Paris, Charles-Henri Sanson, décapite ainsi plus de 3000 personnes en 2 ans (dont le roi Louis XVI et nombre de révolutionnaires)… Finalement dégoûtée par les excès sanglants de la période révolutionnaire, la population va vite reprendre à l’égard des bourreaux son antique mépris.

Les grands changements continuent avec la Révolution. La loi du 13 juin 1793 adoptée par la Convention impose un bourreau par département. Celui-ci recevra un salaire fixe et ne pourra plus prétendre à ses anciens droits féodaux, abolis. Le fait le plus notable est que le bourreau est désormais considéré comme un citoyen comme les autres, ce qui a tendance à faire reculer son statut de paria aux yeux de la population. En 1790, l’Assemblée Nationale décrète l’abolition de la torture, de l’exposition des corps ainsi que l’égalité des supplices, ce qui a comme conséquence de modifier en profondeur les activités des exécuteurs. Ceux-ci utilisent dès 1792 un mode d’exécution unique : la guillotine. Alors que la France est attaquée à ses frontières et que la Révolution se radicalise, le bourreau et sa machine deviennent peu à peu très populaires, ils sont les grands symboles de la libération du peuple et de l’épuration de la société. Le bourreau, qui désormais se salit bien moins les mains avec le nouveau mode d’exécution, devient le « vengeur du peuple » et sa machine à décapiter le « glaive de la liberté ». Il faut dire que la guillotine fonctionne entre 1792 et 1794 à plein régime. A la différence des procédés anciens, elle permet des exécutions continues voire industrielles. Le célèbre bourreau de Paris, Charles-Henri Sanson, décapite ainsi plus de 3000 personnes en 2 ans (dont le roi Louis XVI et nombre de révolutionnaires)… Finalement dégoûtée par les excès sanglants de la période révolutionnaire, la population va vite reprendre à l’égard des bourreaux son antique mépris.

Les éditions Payot viennent de rééditer La Renaissance Orientale de Raymond Schwab, le livre de référence sur les débuts et l’impact des études indiennes et orientales sur les sociétés européennes aux XVIIIe et XIXe siècles. Raymond Schawb (1884-1956) était un authentique humaniste aux multiples facettes : il était traducteur (il pratiquait l'hébreu, le hongrois et l'anglais), romancier et poète. L’Orientalisme a été précédé par un mouvement précurseur, dit pré-indianiste, mouvement animé par des missionnaires ou des fonctionnaires portugais, italiens ou français (en particulier, Anquetil-Duperron, 1731-1805) puis par le pouvoir colonial britannique établi dans la péninsule indienne. Pour ce dernier, l’intérêt linguistique était considéré comme une arme politique pour asseoir sa domination sur le pays.

Les éditions Payot viennent de rééditer La Renaissance Orientale de Raymond Schwab, le livre de référence sur les débuts et l’impact des études indiennes et orientales sur les sociétés européennes aux XVIIIe et XIXe siècles. Raymond Schawb (1884-1956) était un authentique humaniste aux multiples facettes : il était traducteur (il pratiquait l'hébreu, le hongrois et l'anglais), romancier et poète. L’Orientalisme a été précédé par un mouvement précurseur, dit pré-indianiste, mouvement animé par des missionnaires ou des fonctionnaires portugais, italiens ou français (en particulier, Anquetil-Duperron, 1731-1805) puis par le pouvoir colonial britannique établi dans la péninsule indienne. Pour ce dernier, l’intérêt linguistique était considéré comme une arme politique pour asseoir sa domination sur le pays.

Making sense of Heidegger just got a whole lot easier.

Making sense of Heidegger just got a whole lot easier. Each object has meaning within a larger network or “world” of meanings supplied by language, culture, and tradition. Worlds of meaning are collective. In hermeneutics, such contexts of meaning are called “horizons,” for just as the horizon is the boundary of the visible world, horizons are the context in which things have meaning. But what opens up these horizons, these worlds of meaning?

Each object has meaning within a larger network or “world” of meanings supplied by language, culture, and tradition. Worlds of meaning are collective. In hermeneutics, such contexts of meaning are called “horizons,” for just as the horizon is the boundary of the visible world, horizons are the context in which things have meaning. But what opens up these horizons, these worlds of meaning? Heidegger distinguishes between individual instances of openedness, which he calls Dasein, and the structure of human openedness itself, which he calls Existenz and Da-sein (although he is not always consistent about using the hyphen). Sheehan renders the latter two terms as “ex-sistence,” from the Latin ex + sistere, to be forced to stand ahead or beyond. This forced aspect is captured by “openedness” as opposed to mere “openness.”

Heidegger distinguishes between individual instances of openedness, which he calls Dasein, and the structure of human openedness itself, which he calls Existenz and Da-sein (although he is not always consistent about using the hyphen). Sheehan renders the latter two terms as “ex-sistence,” from the Latin ex + sistere, to be forced to stand ahead or beyond. This forced aspect is captured by “openedness” as opposed to mere “openness.”

Ancien responsable de l’excellente revue écologiste radicale Le recours aux forêts, Laurent Ozon est un penseur organique de belle facture. Président-fondateur de l’association Maison Commune, il a publié fin septembre 2014 un recueil d’entretiens intitulé France, les années décisives, puis lancé dans la foulée à Paris le Rassemblement pour un Mouvement de Remigration (R.M.R.). Ses réponses se révèlent pertinentes.

Ancien responsable de l’excellente revue écologiste radicale Le recours aux forêts, Laurent Ozon est un penseur organique de belle facture. Président-fondateur de l’association Maison Commune, il a publié fin septembre 2014 un recueil d’entretiens intitulé France, les années décisives, puis lancé dans la foulée à Paris le Rassemblement pour un Mouvement de Remigration (R.M.R.). Ses réponses se révèlent pertinentes.