È il mese di gennaio del 1970 e i volantini e ciclostilati del GUD, in cui appare il “topo maledetto”, poi circondato da altri personaggi (belle ragazze e squallidi barbuti falsi rivoluzionari), hanno subito un grande successo fra gli studenti. Negli anni successivi Marchal e alcuni dei suoi amici entrano in contatto con l'area giovanile del Msi che fa riferimento a Pino Rauti, in particolare con il dirigente giovanile Marco Tarchi. Dall'esperienza francese di Alternative e dall'entusiasmo di decine di giovani irrequieti e stufi del sonnolento ambiente missino, nel '74 prende il via l'esperimento de La voce della fogna, “giornale differente”, come recitava lo slogan sotto la testata. Un periodico satirico, irriverente, politicamente scorretto nei confronti dello stesso ambiente di provenienza, aperto alle novità non solo politiche, ma anche di costume.

È il mese di gennaio del 1970 e i volantini e ciclostilati del GUD, in cui appare il “topo maledetto”, poi circondato da altri personaggi (belle ragazze e squallidi barbuti falsi rivoluzionari), hanno subito un grande successo fra gli studenti. Negli anni successivi Marchal e alcuni dei suoi amici entrano in contatto con l'area giovanile del Msi che fa riferimento a Pino Rauti, in particolare con il dirigente giovanile Marco Tarchi. Dall'esperienza francese di Alternative e dall'entusiasmo di decine di giovani irrequieti e stufi del sonnolento ambiente missino, nel '74 prende il via l'esperimento de La voce della fogna, “giornale differente”, come recitava lo slogan sotto la testata. Un periodico satirico, irriverente, politicamente scorretto nei confronti dello stesso ambiente di provenienza, aperto alle novità non solo politiche, ma anche di costume.The Enigma of American Fascism in the 1930s

by Michael Kleen

Ex: http://www.alternativeright.com/

In the third decade of the Twentieth Century, as the Great Depression dragged on and the unemployment rate climbed above 20 percent, the United States faced a social and political crisis. Franklin Delano Roosevelt was swept to power in the election of 1932, forcing a political realignment that would put the Democratic Party in the majority for decades. In 1933, President Roosevelt proposed a “New Deal” that he claimed would cure the nation of its economic woes. His plan had many detractors, however, and at the fringes of mainstream politics, disaffected Americans increasingly looked elsewhere for inspiration.

Catholic priest and radio-personality Charles Coughlin’s Christian Front, the German American Bund, the Black Legion, and a variety of nationalist, anti-Semitic, and/or isolationist groups opposed to President Roosevelt, “Moneyed Interests,” and Marxism attracted over a million members and supporters during that decade. Collectively, these groups have long been considered to be a particularly American expression of the same type of fascism that swept Europe in the 1920s and 1930s. The application of the term “fascism” to such a wide variety of individuals and organizations has proved troublesome, however, and the historiography on the subject is conflicted. Did European-style fascism appeal to Americans? Could an “American fascism” have kept the United States out of World War 2?

In order to answer those questions, we must first determine what American fascism was and was not, and then we have to understand why these groups and individuals failed to form any kind of broad coalition against Roosevelt, the New Deal, or liberal democracy itself.

Depending on the historian, American fascism began either as a far-ranging, populist-inspired movement and later degenerated into a number of fringe groups and fanatics, or it began as an isolated phenomenon that lost credibility during the Second World War and simply disappeared. Its adherents either consisted of a wide spectrum of Americans, or of a few thousand recently naturalized immigrants and two or three intellectuals.

“In the United States there were all kinds of fascist or parafascist organizations,” Walter Laqueur asserted in Fascism: Past, Present, Future (1996), “but they never achieved a political breakthrough.”[i] A decade earlier, historian Peter H. Amann took an opposite track. “It seems clear that there were far fewer authentically fascist movements in Depression America than was thought at the time,” he argued.[ii] Conversely, Victor C. Ferkiss, writing in the 1950s, contended that American fascism “was a basically indigenous growth,” and that a broad fascist movement “arose logically from the Populist creed.”[iii]

According to Ferkiss, American fascism was defined as a movement that appealed to farmers and small merchants who felt “crushed between big business . . . and an industrial working class,” espoused nationalism in the form of isolationism, believed that authority came from popular will and not from “liberal democratic institutions” that had been corrupted by moneyed interests, and possessed “an interpretation of history in which the causal factor is the machinations of international financiers.”[iv] According to Peter Amann, all fascism (even the American type) was characterized by an opposition to Marxism and representative government, advocacy of a “revolutionary, authoritarian, nationalist state,” the presence of a charismatic leader and a militarized mass movement, and commonly (although not universally) racist and anti-Semitic views.[v]

These two divergent portrayals, one inclusive and one exclusive, mark the ends of the spectrum in regards to defining fascism in the United States during the 1930s. The former portrays fascism as a legitimate threat to the status quo, and the latter nearly calls its existence into question because so few groups actually fit this model.

American fascism’s cultural roots raise questions as well. Where did the members of these organizations come from? Did American culture encourage or condemn their growth? The data shows a complex picture. American fascism may have been encouraged by some aspects of American culture, but was vigorously condemned by others. The diversity of American interests made a unified fascism that posed a genuine threat to the social order nearly impossible. For instance, while the main constituency of Father Charles Coughlin’s movement was Irish Catholic,[vi] and the members of the German-American Bund mostly recent immigrants,[vii] the Black Legion of the Midwest was fiercely nativist and only accepted Protestants into its ranks.[viii]

What was it about American history and culture doomed openly fascist or fascoid movements? All historians, in their answers, point to our differing conceptions of individual liberty, suspicion of authority, and the commitment to republican government. “No country with a deeply rooted liberal or democratic tradition went fascist,” Peter Amann argued.[ix] For American intellectuals, Victor Ferkiss wrote, “fascism was by definition un-American.”[x] Even the openly racialist and white supremacist South overwhelmingly rejected any comparison to Nazi Germany, and denied it’s Ku Klux Klan had anything to do with fascism.[xi] It seemed that even while incorporating fascist elements, very few Americans openly advocated fascism according to the European model.

Victor C. Ferkiss was far more liberal in his assessment of American fascism than later historians. In his essays “Ezra Pound and American Fascism” (1955) and “Populist Influences on American Fascism” (1957), he attempted to link American fascist groups of the 1930s to the Populist movement of the 1890s, and he broadened the definition of fascism to include prominent aspects of Populism in the United States.

Ezra Pound, American expatriate, poet, and supporter of Benito Mussolini, was the lynchpin of Ferkiss’ argument for an inclusive definition of American fascism. Pound’s ideas, in the widest sense, mirrored those of others in the United States who were known as fascists by their detractors. Ferkiss justified his application of the term by arguing that those individuals and groups “espouse sets of beliefs which have more in common with one another and with European fascism than they do with any other broad area of political thought.”[xii] He listed Huey Long, Gerald L. K. Smith, Father Charles E. Coughlin, and Lawrence Dennis as among those individuals, regardless of how few commonalities their ideas they may have actually shared with European fascist thought.

With this list in hand, Ferkiss held Populism directly responsible for these individual’s fascist tendencies. “American fascism had its roots in American populism,” he declared. “These populist beliefs and attitudes form the core of Pound’s philosophy, just as they provide the basis of American fascism generally.”[xiii] His definition of American fascism followed from that broad interpretation of the commonalities of American fascist thought, even though he acknowledged some fundamental differences. Ezra Pound’s “main divergence from [Lawrence] Dennis is the emphasis which, along with Father Coughlin and Huey Long, he places on the role of finance capitalism as a direct cause of war,” he explained. “For Pound, democracy is a sham.”[xiv]

Ferkiss argued that American fascists viewed the American Revolution as a revolt against the international banking system of England, and that “Mussolini’s objectives are those of Thomas Jefferson,” in his effort to free his country from the power of banks and usury.[xv] That focus on the fascist powers of Europe as defenders of money reform lent to their American supporter’s isolationism, but Ferkiss failed to take into account that approval or agreement does not directly translate into political imitation.

As for the constituency of American fascism, Ferkis argued that “the America First Committee provided the culture in which the seeds of American fascism were to grow.” The AFC was predominantly made up of Midwesterners and a few prominent businessmen, but also had chapters in large Eastern and Western cities. While the AFC was not overtly fascist, “a considerable portion of its chapters were dominated by fascists or their friends,” Ferkiss explained.[xvi] Ezra Pound was also a Midwesterner, having been born in Idaho. He later took a teaching job in Indiana, but he was let go for being “too European” and “unconventional.”[xvii] He emigrated to Europe shortly thereafter.

Written at the same time as Victor Ferkiss’ essays, Joachim Remak’s article “'Friends of the New Germany': The Bund and German-American Relations” (1957) chronicled the nearly universal American reaction against one of the few American fascist groups to consciously model itself after and receive direct inspiration from a European fascist regime: the German-American Bund. Even though the German government forbid its citizens from becoming members of the Bund, and requested that the Bund cease using National Socialist emblems in 1938, most Americans still believed the organization was a foreign entity. “The Americans on its rolls were all of them recent immigrants” from Nazi Germany, Remak explained. “German-Americans had no use for the Bund… the president of the highly conservative Steuben Society called on the [German] embassy to say that his group felt compelled to issue a public repudiation of the Bund.”[xviii]

Remak argued that the German-American Bund, rather than appealing to some broad pro-fascist sympathy in the United States, only harmed relations with National Socialist Germany by demonstrating to Americans the nature of European fascism. “Naziism, with its brutality and its suppression of basic liberties and decencies, could hold no greater appeal for the German-Americans than for the rest of the nation,” he argued.[xix] The rejection of an explicitly fascist organization by those Americans who Victor Ferkiss believed made up the core of ‘American fascism’ is instructive.

Along the same lines, Leland V. Bell, in his book, In Hitler's Shadow: the Anatomy of American Nazism (1973), argued that the real supporters of fascism in the United States were few and far between. In the 1930s, the Nazi party’s pleas for money from American contributors like Henry Ford and the Ku Klux Klan fell on deaf ears. Teutonia, one of the first pro-Nazi groups in the United States, numbered less than one hundred members in 1932, and the typical members of those groups were “young, rootless German immigrants,” and “arrogant, resolute, fanatics.”[xx] When Heinz Spanknoebel formed the Friends of the New Germany in July 1933, “a storm of public protest” greeted them. Four months later, Spanknoebel, like Ezra Pound had earlier, fled the United States.[xxi] The Friends of the New Germany failed to attract significant support from German Americans, who by that time “were accepted, respected citizens and easily assimilated into American life,” Bell explained.[xxii]

In 1936, Fritz Kuhn, a naturalized American citizen who had served in the German army during the First World War, became head of the organization. He renamed it the German-American Bund to attract more American nationals. Most of the constituency of the Bund was made up of recent German immigrants, however, despite Adolf Hitler having banned German citizens from becoming members of the organization. In contrast to Victor Ferkiss’ claim that supporters of American fascism were predominantly rural, the Bund was an urban lower-middle-class movement.[xxiii]

It is clear from Joachim Remak and Leland Bell’s analysis of the German-American Bund that Americans were generally suspicious of overtly fascist groups along the European model. Even the ethnic Germans who had established themselves in the Midwest as farmers and craftsmen, who generally supported isolationism before both World Wars, were not sympathetic to the anti-Democratic, outspokenly pro-Hitler Bundists.

One of the intellectual proponents of American fascism mentioned by Victor Ferkiss was Seward Collins, editor and publisher of the journal American Review. In his article “Seward Collins and the American Review: Experiment in Pro-Fascism, 1933-37” (1960), historian Albert E. Stone argued that Collins’ attempts to “define fascism and apply it to American life” not only produced nothing but controversy, but also undermined his project by alienating his supporters.

Seward Collins’ definition of fascism was unique compared to those covered thus far. According to Stone, Collins amalgamated four schools of thought—two English and two American—which he trumpeted in the American Review: Distributism, Neo-Scholasticism, Humanism, and Southern Agrarianism. Stone explained, “Where these four bodies of thought converged, Collins believed, could be found a definition of fascism which should be offered to thoughtful Americans.”[xxiv] For Seward Collins, fascism meant an end to parliamentary government, but not necessarily an end to democracy. Instead of a president, the head of state would be a monarch― “A strong man at the head of government,”[xxv] which would be coupled by nationalism undivided by rival oppositions.

Collins asserted that the essence of fascism was “the revival of monarchy, property, the guilds, the security of the family and the peasantry, and the ancient ways of European life.”[xxvi] However, that conception of fascism seemed to be a Collins’ own invention and was certainly far afield from the views of Ezra Pound or the German-American Bund. Also, Collins’ espoused anti-Semitism “bore virtually no trace of racial superiority.” He wished to exclude Jews from his fascist state only because they represented social and political rivals, as well as potential dissenters. There was no place in his mind for ideas of Nordic racial superiority, which he called “nonsense.”[xxvii] That would also distinguish him from organizations like the Black Legion and the German-American Bund.

According to Albert Stone, Collins’ views on monarchy and nationalism ultimately alienated one of his important constituencies in the United States, Southern Agrarians. “Southern Agrarians opposed in theory a strong central government,” Stone explained. They were also suspicious of nationalism, deeply isolationist, and “welcomed regional, social and racial differences as healthy manifestations of time, place and tradition.”[xxviii] During a January 1936 interview with the pro-communist magazine FIGHT, Seward Collins colorfully explicated his desire for a monarchy and a return to a medieval society, disparaged liberal education, and voiced admiration for Hitler and Mussolini.

Almost immediately after the interview was published, the American Review’s Southern Agrarian writers left in protest. The Distributists also distanced themselves. Herbert Agar, a prominent member of that bloc, stated, “I would die in order to diminish the chances of fascism in America.”[xxix] The American Review ceased publication in 1937. In the end, it seemed that the majority of Seward Collins’ contributors wanted nothing to do with his views.

In “Vigilante Fascism: The Black Legion as an American Hybrid” (1983) and “A 'Dog in the Nighttime' Problem: American Fascism in the 1930s” (1986), Peter H. Amann argued for a narrow definition of fascism that held closely to the European model and therefore excluded most American groups. Instead, he employed the terms “protofascist” or “fascoid” to describe American organizations that embraced certain aspects or appearances of fascism, but failed to develop into mature fascist political movements.

One such group was the Black Legion, a secret offshoot of the Midwestern Ku Klux Klan. An Ohioan named Dr. William Jacob Shepard formed the Legion during the late 1920s, but never intended the group to take on a life of its own. He was a Northerner who idolized the old South, and he “spouted, and apparently believed, the most rotund platitudes about southern chivalry.”[xxx] He was also a baptized Catholic who hated Catholics, and a doctor who did not shy away from violence.

His Black Legion donned black robes instead of white and held secret initiation rituals. “They were asked to endorse the standard nativist anti-immigrant, anti-Negro, and anti-Catholic positions,” Amann explained, and “pledge support to lynch law.”[xxxi] Initiates were often coaxed or deceived into coming to meetings, and then threatened with death if they did not join.[xxxii] The membership of the Legion was spread across Ohio, Indiana, Michigan, and parts of Illinois, and the majority of members were urban and working class.[xxxiii]

The Black Legion became more violent and more revolutionary as time went on, bringing them closer to the European fascist model. Bert Effinger, their defacto leader during the 1930s, even planned “to kill one million Jews by planting in every American synagogue during Yon Kippur time-clock devices that would simultaneously release mustard gas.”[xxxiv]

Amann argued that the secretive nature of the group prevented them from becoming an effective organization. They were powerful in some ways, but their secrecy made it impossible for them to appeal to a mass audience. No one outside of their organization knew they existed—not even their enemies—so fear and intimidation became a useless tactic. They attempted to create front organizations to infiltrate established political parties but, ultimately, “by pretending to be mere Republicans, Legionnaires ended up acting as mere Republicans.”[xxxv]

Despite their failure, the Black Legion did share many characteristics with European fascist groups. According to Amann, they shared many of the same hatreds, revolutionary goals, and dictatorial tendencies. However, their initiation ceremonies, because of their ultra secrecy, never held the same weight as the mass rallies and rituals of European fascists. Also, the Legion’s nativism was patriotic in a crucial way: the American system may have been corrupt, but there was no alternative to the Constitution or the Republic. Their goal was only to purify the current system, not overthrow it. The history of the Black Legion ultimately shows, Amann argued, that “vigilante nativism and revolutionary-fascism were fundamentally incompatible.”[xxxvi] Additionally, he concluded, “by no stretch of anyone’s imagination can the Black Legion under Dr. Shepard be described as fascist. His Night Riders were to fascism what the Shriners are to Islam.”[xxxvii]

Similarly, the ultra-patriotic societies of the 1930s that evolved into the America First Committee, which Victor Ferkiss believed provided the cultural basis for American fascism, lacked the same crucial ingredients as their alleged European counterparts. “Whatever emphasis prevailed,” Amann explained, “there was never any thought of attacking the American constitutional system, the incumbent politicians, or the two major parties. Nor was there any attempt at mass mobilization.” The Ku Klux Klan, for example, never formed a political party or sought to change the political or economic system of the United States. Therefore, Amann concluded, “the overlap between American nativism and the European type of fascism is… more apparent than real.”[xxxviii]

The nature of these diverse groups also prevented them from working together to present a united front. “The nativist inheritance included… a divisive traditional anti-Catholicism that led the Black Legion to plant explosives in Father Charles Coughlin’s shrine rather than to seek him out as a potential ally,” Peter Amann pointed out.[xxxix] Additionally, genuinely fascist groups like the German-American Bund, with their “aping” of European fascist models, had their patriotic credentials routinely called into question. “It became obvious that in the United States such a nationalism could not be imported from abroad without looking both foolish and unpatriotic,” Amann argued.[xl] A genuine American fascism appealed to very few Americans in the 1930s, and every protofascist organization fell apart the more violent and overtly fascist in appearance and action it became.

In his book Hoods and Shirts: the Extreme Right in Pennsylvania (1997), Philip Jenkins tackled the problem of American fascism from a different angle. He argued that fascism was “polychromatic rather than monotone,” and embraced a spectrum of beliefs across Europe that was also reflected in the United States.[xli] If historians were not hesitant to label such diverse groups as Na Léinte Gorma in Ireland and the Croatian Ustashi (who were lead by church figures and clergymen) as fascist, he reasoned, then they should not be hesitant to label an organization like Father Coughlin’s Christian Front in the same manner.

However, the issue is complicated by the fact that fascist groups in the United States hesitated to call themselves as such. “The organizations most enthusiastic about European Nazism or fascism rarely included these provocative terms in their titles,” he explained. Most often, “Christian” and “Nationalist” were substituted instead because their appeal to American patriotism precluded foreign ideologies. In his own words, “a denial of fascism was phrased as part of a general rejection of any foreign theories.”[xlii]

Father Coughlin’s Christian Front was one of the primary organizations profiled in Hoods and Shirts. According to Jenkins, the Christian Front was founded on “traditions of Irish nationalism” and “anti-British feeling.”[xliii] Although Coughlin himself broadcast his radio messages from Michigan, the Front’s membership was heavily Irish and centered in large cities such as New York, Chicago, Baltimore, Cleveland, Boston and Philadelphia. Jenkins described Father Coughlin as akin to Spanish Nationalist leader Francisco Franco, to whom Coughlin had given moral support during the Spanish Civil War.

Coughlin’s movement linked Jews with communism and saw the Spanish Civil War as a war between good and evil. “Sympathy for Jews was indistinguishable from providing aid and comfort for Communist subversion,” Jenkins explained. The Christian Front allied itself with an assortment of groups, including the German-American Bund, in support of attacks on Jewish synagogues and businesses.[xliv] These activities, along with some outspoken statements in favor of Adolf Hitler, led to the arrest of dozens of movement members. Not all Irish Catholics supported those activities. After one particularly violent incident, an Irish Catholic magistrate “accused the Coughlinites of attempting to spread ‘European’ conditions in Philadelphia.”[xlv] Other Catholics regularly denounced Coughlin in newspapers and journals.[xlvi]

The Christian Front did welcome members from other backgrounds, as evidenced by its willingness to work together with Bund members as well as Italian-Americans. “In New York City over half of all Catholic clergy serving predominantly Italian parishes demonstrated sympathy for the Fascist cause and thus cooperated with the emerging Front,” Jenkins explained.[xlvii] African-American anti-Semites, especially those involved with Black Muslim sects, also attended gatherings and supported Front anti-Jewish activities. Some African Americans in large cities saw Jews as “exploitative landlords and grasping merchants,”[xlviii] which echoed the crusade against “moneyed interests” that was so central to Victor Ferkiss’ definition of American fascism.

As the Second World War broke out in Europe, the Christian Front faced increasing public opposition, as well as persecution by the FBI. Jenkins concluded that both its supporters and its enemies exaggerated the impact of the movement, but it represented one of the only fascoid groups in the United States during the 1930s to have been genuinely domestic in origin. “Of all the activist groups,” he argued, “this had perhaps the greatest potential to become a genuine mass movement around which others could coalesce.”[xlix] Even still, like every other American group on the far right, the political movement it sought to inspire fizzled out when the United States entered the war.

The historical record is very clear. The range of individuals and organizations surveyed by Victor Ferkiss, Peter Amann, and Philip Jenkins all show a similar arch: a steady rise in popularity followed by radicalization, which then ran up against resistance when the group’s activities were exposed. The end result was the rapid dissolution of the organization or the exile of the individual. By 1941, no one who openly came out as being supportive of fascism survived very long in the public eye.

Although a certain cultural undercurrent was needed in order to support the existence of these groups, that cultural undercurrent was undermined by the American democratic tradition they sought to oppose. It seems that, at least in the atmosphere of 1930s America, one could not be both a fascist in any meaningful sense of the word and also be supported by the majority of Americans who saw fascism as a threat to their liberal democratic institutions. The experiences of groups such as the German-American Bund, the Black Legion, Father Coughlin’s Christian Front, and individuals like Seward Collins and Ezra Pound seem to confirm that fascism was by definition a fundamentally “European” phenomenon.

[i] Walter Laqueur, Fascism: Past, Present, Future (New York: Oxford University Press, 1996), 17.

[ii] Peter H. Amann, “A 'Dog in the Nighttime' Problem: American Fascism in the 1930s,” The History Teacher 19 (August 1986): 574.

[iii] Victor C. Ferkiss, “Populist Influences on American Fascism,” The Western Political Quarterly 10 (June 1957): 350, 352.

[iv] Ibid., 350-351.

[v] Amann, 560.

[vi] Ibid., 574.

[vii] Leland V. Bell, In Hitler's Shadow: the Anatomy of American Nazism (Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Press, 1973), 21.

[viii] Peter H. Amann, “Vigilante Fascism: The Black Legion as an American Hybrid,” Comparative Studies in Society and History 25 (July 1983): 496.

[ix] Amann, “A ‘Dog in the Nighttime Problem”: 559.

[x] Ferkiss, “Populist Influences on American Fascism”: 350.

[xi] Johnpeter Horst Grill and Robert L. Jenkins, “The Nazis and the American South in the 1930s: A Mirror Image?,” The Journal of Southern History 58 (November 1992): 688.

[xii] Ferkiss, “Ezra Pound and American Fascism”: 173-4.

[xiii] Ibid., 174.

[xiv] Ibid., 186.

[xv] Ibid., 190.

[xvi] Ferkiss, “Populist Influences on American Fascism”: 367-8.

[xvii] Ferkiss, “Ezra Pound and American Fascism”: 175.

[xviii] Joachim Remak, “'Friends of the New Germany': The Bund and German-American Relations,” The Journal of Modern History 29 (March 1957): 40.

[xix] Ibid., 41.

[xx] Leland V. Bell, In Hitler's Shadow: the Anatomy of American Nazism (Port Washington, NY: Kennikat Press, 1973), 7.

[xxi] Ibid., 13.

[xxii] Ibid., 15-16.

[xxiii] Ibid., 21.

[xxiv] Albert E. Stone, Jr., “Seward Collins and the American Review: Experiment in Pro-Fascism, 1933-37,” American Quarterly 12 (Spring 1960): 6.

[xxv] Ibid., 7.

[xxvi] Ibid., 9.

[xxvii] Ibid., 12.

[xxviii] Ibid., 13.

[xxix] Ibid., 17.

[xxx] Peter H. Amann, “Vigilante Fascism”: 494.

[xxxi] Ibid., 496.

[xxxii] Ibid., 498.

[xxxiii] Ibid., 509.

[xxxiv] Ibid., 512.

[xxxv] Ibid., 515.

[xxxvi] Ibid., 524.

[xxxvii] Ibid., 501.

[xxxviii] Peter H. Amann, “A 'Dog in the Nighttime' Problem”: 562.

[xxxix] Ibid., 567.

[xl] Ibid., 569.

[xli] Philip Jenkins, Hoods and Shirts: the Extreme Right in Pennsylvania, 1925-1950 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1997), 27.

[xlii] Ibid., 25-26.

[xliii] Ibid., 166.

[xliv] Ibid., 173.

[xlv] Ibid., 174.

[xlvi] Ibid., 187-8.

[xlvii] Ibid., 183.

[xlviii] Ibid., 185.

[xlix] Ibid., 191.

Michael Kleen

Michael Kleen is the Editor-in-Chief of Untimely Meditations, publisher of Black Oak Presents, and proprietor of Black Oak Media. He holds a master’s degree in American history and is the author of The Britney Spears Culture, a collection of columns regarding issues in contemporary American politics and culture. His columns have appeared in various publications and websites, including the Rock River Times, Daily Eastern News, World Net Daily, and Strike-the-Root.

Einem Monarchisten jüdischen Glaubens, Hans-Joachim Schoeps (1909-1980), fühle ich mich schon längst schicksalsgemeinschaftlich zugetan. Als seine preußischen Vorfahren, der Hohenzollern-Hausmacht huldigend, im Ersten Weltkrieg zu Felde zogen, meldete sich zeitgleich mein öesterreichisch-jüdischer Onkel zum Kriegsdienst. Auch als Greis mit steigender Hinfälligkeit schlug sich Schoeps gegen Deutschhasser jeder Couleur und vor allem gegen die Verächter des preußischen Erbguts. Außerdem trat er mutig der Beschimpfung entgegen, dass er gegen die von den Alliierten installierte Demokratie als „jüdischer Nazi“ antrat.

Einem Monarchisten jüdischen Glaubens, Hans-Joachim Schoeps (1909-1980), fühle ich mich schon längst schicksalsgemeinschaftlich zugetan. Als seine preußischen Vorfahren, der Hohenzollern-Hausmacht huldigend, im Ersten Weltkrieg zu Felde zogen, meldete sich zeitgleich mein öesterreichisch-jüdischer Onkel zum Kriegsdienst. Auch als Greis mit steigender Hinfälligkeit schlug sich Schoeps gegen Deutschhasser jeder Couleur und vor allem gegen die Verächter des preußischen Erbguts. Außerdem trat er mutig der Beschimpfung entgegen, dass er gegen die von den Alliierten installierte Demokratie als „jüdischer Nazi“ antrat.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Unlike Edmund Burke and Joseph de Maistre, Louis de Bonald devoted little space to analyzing the French Revolution itself. His focus instead was on understanding the traditional society which had been swept away. His review of Mme. de Staël’s

Unlike Edmund Burke and Joseph de Maistre, Louis de Bonald devoted little space to analyzing the French Revolution itself. His focus instead was on understanding the traditional society which had been swept away. His review of Mme. de Staël’s  Son tiempos estos los que corren donde el heroísmo y la entrega, sacrificando para ello su vida si fuera preciso, es considerado un acto de idealismo estúpido; época la nuestra en que la Juventud, en mayúscula, ha dejado de tener sentido para convertirse en una mera comparsa de la sociedad de consumo. Parece que esta edad es más una técnica de mercado. El desánimo cunde entre las filas de aquellos que aún ven, nadie cree que exista el menor resquicio por donde destruir esta desidia colectiva. Muchos se resguardan en la nostalgia y en los recuerdos de años pasados, incluso los más jóvenes que no lo vivimos nos aislamos y preferimos las glorias del pasado a la dura lucha del día a día por rescatarlo. Es más fácil.

Son tiempos estos los que corren donde el heroísmo y la entrega, sacrificando para ello su vida si fuera preciso, es considerado un acto de idealismo estúpido; época la nuestra en que la Juventud, en mayúscula, ha dejado de tener sentido para convertirse en una mera comparsa de la sociedad de consumo. Parece que esta edad es más una técnica de mercado. El desánimo cunde entre las filas de aquellos que aún ven, nadie cree que exista el menor resquicio por donde destruir esta desidia colectiva. Muchos se resguardan en la nostalgia y en los recuerdos de años pasados, incluso los más jóvenes que no lo vivimos nos aislamos y preferimos las glorias del pasado a la dura lucha del día a día por rescatarlo. Es más fácil.

Dans ce magma de brics et de brocs, de débris de choses jadis glorieuses, flotte un roman étonnant, celui de Gaston Compère [photo], écrivain complexe, à facettes diverses, avant-gardiste de la poésie, parfois baroque, et significativement intitulé « Je soussigné, Charles le Téméraire, Duc de Bourgogne ». Né dans le Condroz namurois en novembre 1924, Gaston Compère a mené une vie rangée de professeur d’école secondaire, tout en se réfugiant, après ses cours, dans une littérature particulière, bien à lui, où théâtre, prose et poésie se mêlent, se complètent. Dans le roman consacré au Duc, Compère use d’une technique inhabituelle : faire une biographique non pas racontée par un tiers extérieur à la personne trépassée, mais par le « biographé » lui-même. Le roman est donc un long monologue du Duc, approximativement deux ou trois cent ans après sa mort sur un champ de bataille près de Nancy en 1477. Compère y glisse toutes les réflexions qu’il a lui-même eues sur la mort, sur le destin de l’homme, qu’il soit simple quidam ou chef de guerre, obscur ou glorieux. Les actions de l’homme, du chef, volontaires ou involontaires, n’aboutissent pas aux résultats escomptés, ou doivent être posées, envers et contre tout, même si on peut parfaitement prévoir le désastre très prochain, inéluctable, qu’elles engendreront. Ensuite, Compère, musicologue spécialiste de Bach, fait dire au Duc toute sa philosophie de la musique, qu’il définit comme « formalisation intelligible du mystère de l’existence » ou comme « détentrice du vrai savoir ». Pour Compère, « la philosophie est un discours sur les choses et en marge d’elles ». « Si la musique, ajoute-t-il, pouvait prendre sa place, nous connaîtrions selon la musique et en elle. Alors, notre connaissance ne resterait pas extérieure ; au contraire, elle occuperait le cœur de l’être ».

Dans ce magma de brics et de brocs, de débris de choses jadis glorieuses, flotte un roman étonnant, celui de Gaston Compère [photo], écrivain complexe, à facettes diverses, avant-gardiste de la poésie, parfois baroque, et significativement intitulé « Je soussigné, Charles le Téméraire, Duc de Bourgogne ». Né dans le Condroz namurois en novembre 1924, Gaston Compère a mené une vie rangée de professeur d’école secondaire, tout en se réfugiant, après ses cours, dans une littérature particulière, bien à lui, où théâtre, prose et poésie se mêlent, se complètent. Dans le roman consacré au Duc, Compère use d’une technique inhabituelle : faire une biographique non pas racontée par un tiers extérieur à la personne trépassée, mais par le « biographé » lui-même. Le roman est donc un long monologue du Duc, approximativement deux ou trois cent ans après sa mort sur un champ de bataille près de Nancy en 1477. Compère y glisse toutes les réflexions qu’il a lui-même eues sur la mort, sur le destin de l’homme, qu’il soit simple quidam ou chef de guerre, obscur ou glorieux. Les actions de l’homme, du chef, volontaires ou involontaires, n’aboutissent pas aux résultats escomptés, ou doivent être posées, envers et contre tout, même si on peut parfaitement prévoir le désastre très prochain, inéluctable, qu’elles engendreront. Ensuite, Compère, musicologue spécialiste de Bach, fait dire au Duc toute sa philosophie de la musique, qu’il définit comme « formalisation intelligible du mystère de l’existence » ou comme « détentrice du vrai savoir ». Pour Compère, « la philosophie est un discours sur les choses et en marge d’elles ». « Si la musique, ajoute-t-il, pouvait prendre sa place, nous connaîtrions selon la musique et en elle. Alors, notre connaissance ne resterait pas extérieure ; au contraire, elle occuperait le cœur de l’être ».

Assez récemment, les éditions Bartillat ont eu l’excellente idée de rééditer Ernst von Salomon, auteur culte, certes, mais seulement pour un petit nombre d’adeptes. Et ses livres majeurs n’étaient plus disponibles depuis plusieurs années. Jean Mabire notait, dans son Que lire ? de 1996, pour le regretter, que « la mort d’Ernst von Salomon, en 1972 n’avait « pas fait grand bruit, et, aujourd’hui, on parle fort peu de cet écrivain singulier ».

Assez récemment, les éditions Bartillat ont eu l’excellente idée de rééditer Ernst von Salomon, auteur culte, certes, mais seulement pour un petit nombre d’adeptes. Et ses livres majeurs n’étaient plus disponibles depuis plusieurs années. Jean Mabire notait, dans son Que lire ? de 1996, pour le regretter, que « la mort d’Ernst von Salomon, en 1972 n’avait « pas fait grand bruit, et, aujourd’hui, on parle fort peu de cet écrivain singulier ». Le roman La Ville parait en 1932 (en 1933 en France). C’est le portrait d’un agitateur vagabondant dans le radicalisme absolu, c’est encore une sorte d’autobiographie, autour de ses engagements « paysans ».

Le roman La Ville parait en 1932 (en 1933 en France). C’est le portrait d’un agitateur vagabondant dans le radicalisme absolu, c’est encore une sorte d’autobiographie, autour de ses engagements « paysans ».

(1) Sur le salut nazi, Fabrice Bouthillon affirme : «Ce geste fasciste par excellence, qu’est le salut de la main tendue, n’est-il pas au fond né à Gauche ? N’a-t-il pas procédé d’abord de ces votes à main levée dans les réunions politiques du parti, avant d’être militarisé ensuite par le raidissement du corps et le claquement des talons – militarisé et donc, par là, droitisé, devenant de la sorte le symbole le plus parfait de la capacité nazie à faire fusionner, autour de Hitler, valeurs de la Gauche et valeurs de la Droite ? Car il y a bien une autre origine possible à ce geste, qui est la prestation de serment le bras tendu; mais elle aussi est, en politique, éminemment de Gauche, puisque le serment prêté pour refonder, sur l’accord des volontés individuelles, une unité politique dissoute, appartient au premier chef à la liste des figures révolutionnaires obligées, dans la mesure même où la dissolution du corps politique, afin d’en procurer la restitution ultérieure, par l’engagement unanime des ex-membres de la société ancienne, est l’acte inaugural de toute révolution. Ainsi s’explique que la prestation du serment, les mains tendues, ait fourni la matière de l’une des scènes les plus topiques de la révolution française – et donc aussi, qu’on voie se dessiner, derrière le tableau par Hitler du meeting de fondation du parti nazi, celui, par David, du Serment du Jeu de Paume» (p. 171).

(1) Sur le salut nazi, Fabrice Bouthillon affirme : «Ce geste fasciste par excellence, qu’est le salut de la main tendue, n’est-il pas au fond né à Gauche ? N’a-t-il pas procédé d’abord de ces votes à main levée dans les réunions politiques du parti, avant d’être militarisé ensuite par le raidissement du corps et le claquement des talons – militarisé et donc, par là, droitisé, devenant de la sorte le symbole le plus parfait de la capacité nazie à faire fusionner, autour de Hitler, valeurs de la Gauche et valeurs de la Droite ? Car il y a bien une autre origine possible à ce geste, qui est la prestation de serment le bras tendu; mais elle aussi est, en politique, éminemment de Gauche, puisque le serment prêté pour refonder, sur l’accord des volontés individuelles, une unité politique dissoute, appartient au premier chef à la liste des figures révolutionnaires obligées, dans la mesure même où la dissolution du corps politique, afin d’en procurer la restitution ultérieure, par l’engagement unanime des ex-membres de la société ancienne, est l’acte inaugural de toute révolution. Ainsi s’explique que la prestation du serment, les mains tendues, ait fourni la matière de l’une des scènes les plus topiques de la révolution française – et donc aussi, qu’on voie se dessiner, derrière le tableau par Hitler du meeting de fondation du parti nazi, celui, par David, du Serment du Jeu de Paume» (p. 171). Proudhon, qui, en 1863 déjà, proclamait la nécessité « du principe fédératif », mettait ses disciples en garde contre cette déformation et cet abus. De cet ouvrage fameux, il est de bon ton de répéter une phrase : « Le vingtième siècle ouvrira l’ère des fédérations, ou l’humanité recommencera un purgatoire de mille ans » et d’en citer … implicitement une autre, en négligeant d’en Indiquer la source : « L’Europe serait encore trop grande pour une confédération unique : elle ne pourrait former qu’une confédération de confédérations ». Il semble que ce soit là tout ce qu’on ait retenu de ce traité fondamental. N’oublie-t-on pas un peu trop facilement avec quelle force il s’est lui-même déclaré « républicain, mais irréductiblement hostile au républicanisme tel que l’ont défiguré les jacobins » ? N’oublie-t-on pas qu’aucune insistance ne lui paraissait indiscrète quand il s’agissait de répéter à ses correspondants : « Méfiez-vous des jacobins qui sont les vrais ennemis de toutes les libertés, des unitaristes, des nationalistes, etc … »

Proudhon, qui, en 1863 déjà, proclamait la nécessité « du principe fédératif », mettait ses disciples en garde contre cette déformation et cet abus. De cet ouvrage fameux, il est de bon ton de répéter une phrase : « Le vingtième siècle ouvrira l’ère des fédérations, ou l’humanité recommencera un purgatoire de mille ans » et d’en citer … implicitement une autre, en négligeant d’en Indiquer la source : « L’Europe serait encore trop grande pour une confédération unique : elle ne pourrait former qu’une confédération de confédérations ». Il semble que ce soit là tout ce qu’on ait retenu de ce traité fondamental. N’oublie-t-on pas un peu trop facilement avec quelle force il s’est lui-même déclaré « républicain, mais irréductiblement hostile au républicanisme tel que l’ont défiguré les jacobins » ? N’oublie-t-on pas qu’aucune insistance ne lui paraissait indiscrète quand il s’agissait de répéter à ses correspondants : « Méfiez-vous des jacobins qui sont les vrais ennemis de toutes les libertés, des unitaristes, des nationalistes, etc … » Che

Che

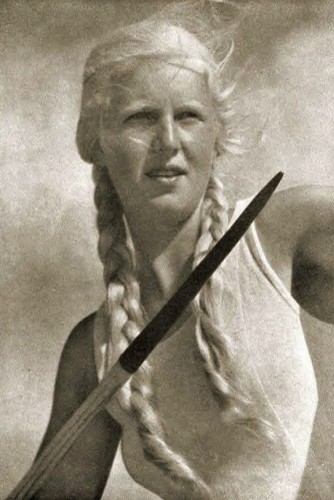

National Socialism promoted two images of woman: the hardworking peasant mother in traditional dress, and the uniformed woman in service to her people. Both images were an attempt to combat two types of woman that are foreign to Traditional European societies: the Aphrodisian and Amazonian woman.

National Socialism promoted two images of woman: the hardworking peasant mother in traditional dress, and the uniformed woman in service to her people. Both images were an attempt to combat two types of woman that are foreign to Traditional European societies: the Aphrodisian and Amazonian woman. These were the Aphrodisian elements that had made their way into the Weimar Republic and Third Reich, and which the National Socialists tried to restrain, along with modern Amazonian woman (the unmarried, childless, career woman in mannish dress). The Aphrodite type was represented by the “movie ‘star’ or some similar fascinating Aphrodisian apparition.”[6] In his introduction to the writings of Bachofen, National Socialist scholar Alfred Baeumler wrote that the modern world has all of the characteristics of a gynaecocratic age. In writing about the European city-woman, he says, “The fascinating female is the idol of our times, and, with painted lips, she walks through the European cities as she once did through Babylon.”[7]

These were the Aphrodisian elements that had made their way into the Weimar Republic and Third Reich, and which the National Socialists tried to restrain, along with modern Amazonian woman (the unmarried, childless, career woman in mannish dress). The Aphrodite type was represented by the “movie ‘star’ or some similar fascinating Aphrodisian apparition.”[6] In his introduction to the writings of Bachofen, National Socialist scholar Alfred Baeumler wrote that the modern world has all of the characteristics of a gynaecocratic age. In writing about the European city-woman, he says, “The fascinating female is the idol of our times, and, with painted lips, she walks through the European cities as she once did through Babylon.”[7] The earliest Europeans tended toward simplicity in dress and appearance. Adornments were used solely to signify caste or heroic deeds, or were amulets or talismans. In ancient Greece, jewels were never worn for everyday use, but reserved for special occasions and public appearances. In Rome, also, jewelry was thought to have a spiritual power.[11] Western fashion often was used to display rank, as in Roman patricians’ purple sash and red shoes. The Mediterranean cultures, influenced by the East, were the first to become extravagant in dress and makeup. By the time this influence spread to northern Europe, it had been Christianized, and makeup did not appear again in northern Europe until the fourteenth century, after which followed a long period of its association with immorality.[12]

The earliest Europeans tended toward simplicity in dress and appearance. Adornments were used solely to signify caste or heroic deeds, or were amulets or talismans. In ancient Greece, jewels were never worn for everyday use, but reserved for special occasions and public appearances. In Rome, also, jewelry was thought to have a spiritual power.[11] Western fashion often was used to display rank, as in Roman patricians’ purple sash and red shoes. The Mediterranean cultures, influenced by the East, were the first to become extravagant in dress and makeup. By the time this influence spread to northern Europe, it had been Christianized, and makeup did not appear again in northern Europe until the fourteenth century, after which followed a long period of its association with immorality.[12]

Il suo nome ai più non dirà molto. Ma Niccolò Giani fu uno dei più importanti, radicali e oltranzisti esponenti del Fascismo rivoluzionario. Fu, infatti, tra i fondatori, nonché uno dei massimi rappresentanti, della Scuola di Mistica Fascista (SMF). Vissuto il suo ideale fino all’ultimo respiro, morì combattendo sul fronte greco nel 1941, ricevendo, per l’esempio offerto, la medaglia d’oro al valore. Tutto questo, mentre molti “fascisti” – le virgolette sono d’obbligo – s’imboscavano in patria, nascondendosi dietro la retorica di vuoti slogan e sterili parole d’ordine. Quegli stessi che, dopo il 1945, seppero bene in che direzione riciclarsi.

Il suo nome ai più non dirà molto. Ma Niccolò Giani fu uno dei più importanti, radicali e oltranzisti esponenti del Fascismo rivoluzionario. Fu, infatti, tra i fondatori, nonché uno dei massimi rappresentanti, della Scuola di Mistica Fascista (SMF). Vissuto il suo ideale fino all’ultimo respiro, morì combattendo sul fronte greco nel 1941, ricevendo, per l’esempio offerto, la medaglia d’oro al valore. Tutto questo, mentre molti “fascisti” – le virgolette sono d’obbligo – s’imboscavano in patria, nascondendosi dietro la retorica di vuoti slogan e sterili parole d’ordine. Quegli stessi che, dopo il 1945, seppero bene in che direzione riciclarsi.

Nazi Fashion Wars:

The Evolian Revolt Against Aphroditism in the Third Reich, Part 2

Judaism is not historically opposed to cosmetics and jewelry, although two stories can be interpreted as negative indictments on cosmetics and too much finery: Esther rejected beauty treatments before her presentation to the Persian king, indicating that the highest beauty is pure and natural; and Jezebel, who dressed in finery and eye makeup before her death, may the root of some associations between makeup and prostitutes.

In most cases, however, Jewish views on cosmetics and jewelry tend to be positive and indicate woman’s role as sexual: “In the rabbinic culture, ornamentation, attractive dress and cosmetics are considered entirely appropriate to the woman in her ordained role of sexual partner.” In addition to daily use, cosmetics also are allowed on holidays on which work (including painting, drawing, and other arts) are forbidden; the idea is that since it is pleasurable for women to fix themselves up, it does not fall into the prohibited category of work.[1]

In addition to the historical distinctions between cultures on cosmetics, jewelry, and fashion, the modern era has demonstrated that certain races enter industries associated with the Aphrodisian worldview more than others. Overwhelmingly, Jews are overrepresented in all of these arenas. Following World War I, the beauty and fashion industries became dominated by huge corporations, many of the Jewish-owned. Of the four cosmetics pioneers — Helena Rubenstein, Elizabeth Arden, Estée Lauder (née Mentzer), and Charles Revson (founder of Revlon) — only Elizabeth Arden was not Jewish. In addition, more than 50 percent of department stores in America today were started or run by Jews. (Click here for information about Jewish department stores and jewelers, and here for Jewish fashion designers).

Hitler was not the only one who noticed Jewish influence in fashion and thought it harmful. Already in Germany, a belief existed that Jewish women were “prone to excess and extravagance in their clothing.” In addition, Jews were accused of purposefully denigrating women by designing immoral, trashy clothing for German women.[2] There was an economic aspect to the opposition of Jews in fashion, as many Germans thought them responsible for driving smaller, German-owned clothiers out of business. In 1933, an organization was founded to remove Jews from the Germany fashion industry. Adefa “came about not because of any orders emanating from high within the state hierarchy. Rather, it was founded and membered by persons working in the fashion industry.”[3] According to Adefa’s figures, Jewish participation was 35 percent in men’s outerwear, hats, and accessories; 40 percent in underclothing; 55 percent in the fur industry; and 70 percent in women’s outerwear.[4]

Although many Germans disliked the Jewish influence in beauty and fashion, it was recognized that the problem was not so much what particular foreign race was impacting German women, but that any foreign influence was shaping their lives and altering their spirit. The Nazis obviously were aware of the power of dress and beauty regimes to impact the core of woman’s self-image and being. According to Agnes Gerlach, chairwoman for the Association for German Women’s Culture:

Not only is the beauty ideal of another race physically different, but the position of a woman in another country will be different in its inclination. It depends on the race if a woman is respected as a free person or as a kept female. These basic attitudes also influence the clothes of a woman. The southern ‘showtype’ will subordinate her clothes to presentation, the Nordic ‘achievement type’ to activity. The southern ideal is the young lover; the Nordic ideal is the motherly woman. Exhibitionism leads to the deformation of the body, while being active obligates caring for the body. These hints already show what falsifying and degenerating influences emanate from a fashion born of foreign law and a foreign race.[5]

Gerlach’s statements echo descriptions of Aphrodisian cultures entirely: Some cultures view women as a sex object, and elements of promiscuity run through all areas of women’s dress and toilette; Aryan cultures have a broader understanding of the possibilities of the female being and celebrate woman’s natural beauty.

The Introduction of Aphrodisian Elements into Germany and the Beginning of the Fashion Battles

Long before the Third Reich, Germans battled the French on the field of fashion; it was a battle between the Aphrodisian culture that had made its way to France, and the Demetrian placement of woman as a wife and mother. As early as the 1600s, German satirical picture sheets were distributed that showed the “Latin morals, manners, customs, and vanity” of the French as threatening Nordic culture in Germany. In the twentieth century, Paris was the height of high fashion, and as tensions between the two countries increased, the French increased their derogatory characterizations of German women for not being stereotypically Aphrodisian. In 1914, a Parisian comic book presented Germans as “a nation of fat, unrefined, badly dressed clowns.”[6] And in 1917, a French depiction of “Virtuous Germania” shows her as “a fat, large-breasted, mean-looking woman, with a severe scowl on her chubby face.”[7]

Hitler saw the French fashion conglomerate as a manifestation of the Jewish spirit, and it was common to hear that Paris was controlled by Jews. Women were discouraged from wearing foreign modes of dress such as those in the Jewish and Parisian shops: “Sex appeal was considered to be ‘Jewish cosmopolitanism’, whilst slimming cures were frowned upon as counter to the birth drive.”[8] Thus, the Nazis staunch stance against anything French was in part a reaction to the Latin qualities of French culture, which had migrated to the Mediterranean thousands of years earlier, and that set the highest image of woman as something German men did not want: “a frivolous play toy that superficially only thinks about pleasure, adorns herself with trinkets and spangles, and resembles a glittering vessel, the interior of which is hollow and desolate.”[9] Such values had no place in National Socialism, which promoted autarky, frugalness, respect for the earth’s resources, natural beauty, a true religiosity (Christian at first, with the eventual goal to return to paganism), devotion to higher causes (such as to God and the state), service to one’s community, and the role of women as a wife and mother.

Opposition to the Aphrodisian Culture in the Third Reich

Most students of Third Reich history are familiar with the more popular efforts to shape women’s lives: the Lebensborn program for unwed mothers, interest-free loans for marriage and children, and propaganda posters that emphasized health and motherhood. But some of the largest battles in the fight for women occurred almost entirely within the sphere of fashion—in magazines, beauty salons, and women’s organizations.

The Nazis did not discount fashion, only its Aphrodisian manifestations. On the contrary, they understood fashion as a powerful political tool in shaping the mores of generations of women. Fashion and beauty also were recognized as important elements in the cultural revolution that is necessary for lasting political change. German author Stafan Zweig commented on fashion in the 1920s:

Today its dictatorship becomes universal in a heartbeat. No emperor, no khan in the history of the world ever experienced a similar power, no spiritual commandment a similar speed. Christianity and socialism required centuries and decades to win their followings, to enforce their commandments on as many people as a modern Parisian tailor enslaves in eight days.[10]

Thus, Nazi Germany established a fashion bureau and numerous women’s organizations as active forces of cultural hegemony. Gertrud Scholtz-Klink, the national leader of the NS-Frauenschaft (NSF, or National Socialist Women’s League), said the organization’s aim was to show women how their small actions could impact the entire nation.[11] Many of these “small actions” involved daily choices about dress, shopping, health, and hygiene.

The biggest enemies of women, according to the Nazi regime, were those un-German forces that worked to denigrate the German woman. These included Parisian high fashion and cosmetics, Jewish fashion, and the Hollywood image of the heavily made up, cigarette-smoking vamp—the archetype of the Aphrodisian. These forces not only impacted women’s clothing, personal care choices, and activities, but were dangerous since they touched the German woman’s very spirit.

Clothing should not now suddenly return to the Stone Age; one should remain where we are now. I am of the opinion that when one wants a coat made, one can allow it to be made handsomely. It doesn’t become more expensive because of that. . . . Is it really something so horrible when [a woman] looks pretty? Let’s be honest, we all like to see it.[14]

Though understanding the need for tasteful and beautiful dress, the Nazis were adamantly against elements foreign to the Nordic spirit. The list included foreign fashion, trousers, provocative clothing, cosmetics, perfumes, hair alterations (such as coloring and permanents), extensive eyebrow plucking, dieting, alcohol, and smoking. In February 1916, the government issued a list of “forbidden luxury items” that included foreign (i.e., French) cosmetics and perfumes.[15] Permanents and hair coloring were strongly discouraged. Although the Nazis were against provocative clothing in everyday dress, they encouraged sportiness and were certainly not prudish about young girls wearing shorts to exercise. A parallel can be seen in the scanty dress worn by Spartan girls during their exercises, a civilization characterized by its Nordic spirit and solar-orientation.

Some have said that Hitler was opposed to cosmetics because of his vegetarian leanings, since cosmetics were made from animal byproducts. More likely, he retained the same views that kept women from wearing makeup for centuries in Western countries—the innate understanding that the Aphrodisian woman is opposed to Aryan culture. Nazi proponents said “red lips and painted cheeks suited the ‘Oriental’ or ‘Southern’ woman, but such artificial means only falsified the true beauty and femininity of the German woman.”[16] Others said that any amount of makeup or jewelry was considered “sluttish.”[17] Magazines in the Third Reich still carried advertisements for perfumes and cosmetics, but articles started advocating minimal, natural-looking makeup, for the truth was that most women were unable to pull off a fresh and healthy image without a little help from cosmetics.

Although jewelry and cosmetics were not banned, many areas of the Third Reich were impossible to enter unless conforming to Nazi ideals. In 1933, “painted” women were banned from Kreisleitung party meetings in Breslau. Women in the Lebensborn program were not allowed to use lipstick, pluck their eyebrows, or paint their nails.[18] When in uniform, women were forbidden to wear conspicuous jewelry, brightly colored gloves, bright purses, and obvious makeup.[19] The BDM also was influential in shaping fashion in the regime, with young girls taking up the use of clever pejoratives to reinforce the regime’s message that unnatural beauty was not Aryan. The Reich Youth Leader said:

The BDM does not subscribe to the untruthful ideal of a painted and external beauty, but rather strives for an honest beauty, which is situated in the harmonious training of the body and in the noble triad of body, soul, and mind. Staunch BDM members whole-heartedly embraced the message, and called those women who cosmetically tried to attain the Aryan female ideal ‘n2 (nordic ninnies)’ or ‘b3 (blue-eyed, blonde blithering idiots).’[20]

The Nazis offered many alternatives to Aphrodisian values: beauty would be derived from good character, exercise outdoors, a good diet, healthy skin free of the harsh chemicals in makeup, comfortable (yet still stylish and flattering) clothing, and from the love for her husband, children, home, and country. The most encouraged hairstyles were in buns or plaits—styles that saved money on trips to the beauty salon and were seen as more wholesome and befitting of the German character. In fact, Tracht (traditional German dress) was viewed as not merely clothing, but also as “the expression of a spiritual demeanor and a feeling of worth . . . Outwardly, it conveys the expression of the steadfastness and solid unity of the rural community.”[21] Foreign clothing designs, according to Gerlach, led to physical and “psychological distortion and damage, and thereby to national and racial deterioration.”[22]

* * *

Some people may be inclined to interpret Aphrodisian culture as positive for the sexes—it puts the emphasis for women not on careers but on their existence as sexual beings. Men often encourage such behavior by their dating choices and by complimenting an Aphrodisian “look” in women. But Aphrodisian culture is not only damaging to women, as Bachofen relates, by reducing them to the status of sex slave of multiple men. It also is degrading for men, at the level of personality and at the deepest levels of being. As Evola writes about the degeneration into Aphroditism:

The chthonic and infernal nature penetrates the virile principle and lowers it to a phallic level. The woman now dominates man as he becomes enslaved to the senses and a mere instrument of procreation. Vis-à-vis the Aphrodistic goddess, the divine male is subjected to the magic of the feminine principle and is reduced to the likes of an earthly demon or a god of the fecundating waters—in other words, to an insufficient and dark power.[23]

(PICTURE: Swedish singer Zarah Leander)

If someone needs the ‘unusual’ to be moved to astonishment, that person has lost the ability to respond rightly to the wondrous, the mirandum, of being. The hunger for the sensational . . . is an unmistakable sign of the loss of the true power of wonder, for a bourgeois-ized humanity.[24]

A society that promotes so much unnatural beauty will no doubt lose the ability to experience the wondrous in the natural. It is essential that people retain the ability to love and be moved by the pure and natural, in order to once again return to a civilization centered in a Traditional Aryan worldview.

Notes

1. Daniel Boyarin, “Sex,” Jewish Women’s Archive.

2. Irene Guenther, Nazi ‘Chic’?: Fashioning Women in the Third Reich (Oxford: Berg, 2004), 50–51.

(Oxford: Berg, 2004), 50–51.

3. Guenther, 16.

4. Guenther, 159.

5. Agnes Gerlach, quoted in Guenther, 146.

6. Guenther, 21–22.

7. Guenther, 26.

8. Matthew Stibbe, “Women and the Nazi state,” History Today, vol. 43, November 1993.

9. Guenther, 93.

10. Stefan Zweig, quoted in Guenther, 9.

11. Jill Stephenson, Women in Nazi Germany (Essex, UK: Pearson, 2001), 88.

(Essex, UK: Pearson, 2001), 88.

12. Stephenson, 133.

13. Guenther, 120.

14. Adolf Hitler, quoted in Guenther, 141.

15. Guenther, 32.

16. Guenther, 100.

17. Guido Knopp, Hitler’s Women (New York: Routledge, 2003), 231.

(New York: Routledge, 2003), 231.

18. Guenther, 99.

19. Guenther, 129.

20. Guenther, 121.

21. Guenther, 111.

22. Gerlach, quoted in Guenther, 145.

23. Evola, Revolt, 223.

24. Josef Pieper, Leisure: The Basis of Culture , trans. Gerald Malsbary (South Bend, Ind.: St. Augustine’s Press, 1998), 102.

, trans. Gerald Malsbary (South Bend, Ind.: St. Augustine’s Press, 1998), 102.