vendredi, 10 juin 2011

1940: l'autre uchronie

1940 : l’autre uchronie

par Noël RIVIÈRE

L’uchronie est l’histoire fictive de possibilités historiques non advenues. Elle aide à comprendre ce qui a réellement eu lieu en poussant les logiques des autres scénarios envisageables tout en respectant une certaine vraisemblance. Les uchronies sont de plus en plus l’objet de travaux. L’un des derniers en date est celui de Jacques Sapir sur le thème « Et si la France n’avait pas signé l’armistice de 1940 et avait continué la guerre ? » C’est le What if : que se serait-il passé si… Les uchronies nécessitent de tenir compte des informations dont disposaient les protagonistes au moment des faits.

Il est en ce moment à la mode de dérouler un scénario à propos de la guerre de 39-45 : Et si la France avait continué la guerre ? (Jacques Sapir et aa, Taillandier, 2010).

Pierre Clostermann lui-même avait défendu l’idée que les forces français en Afrique du nord, en 1940 auraient permis de continuer la guerre. Reste à savoir pour quel résultat. Un résultat qui aurait peut-être au final été particulièrement favorable à l’Allemagne. Explications.

Supposons donc une absence d’armistice le 22 juin 1940.

Fin juin, les Allemands sont à Marseille, Nice, Perpignan et sur la côte basque. Compte tenu de leur maîtrise de l’air, ils investissent la Corse sans grande difficulté et obligent bien avant cela la flotte française à se replier en Algérie, sauf destruction totale ou partielle comme celle qu’a connue la flotte italienne face aux Anglais dans le golfe de Tarente, en 1940, voire au cap Matapan, en 1941, toujours face à l’aviation anglaise. À partir de là, les Français continuant la guerre, les Allemands n’eussent eu d’autres choix que de les poursuivre en Afrique du Nord. On lit parfois le propos comme quoi les Allemands n’ont même pas pu franchir la Manche ou le Pas de Calais et que donc ils auraient été bien en peine de franchir la Méditerranée. Cela n’a rien à voir. Derrière la Manche, il y a avait une nation industrielle de cinquante millions d’habitants. En Algérie – l’A.F.N., c’était essentiellement l’Algérie – il y avait sept millions d’habitants dont moins d’un million de Pieds-Noirs. Peu d’industrie et presque pas de pièces de rechanges pour les armes. Autant dire que les Allemands auraient pu débarquer sans se heurter à une résistance comparable à celle de la Royal Air Force au-dessus de la côte anglaise en août-septembre 1940.

Mais surtout ils avaient l’alliance italienne. Un débarquement à Tunis aurait été à une extrême proximité de la Sicile – et les Allemands ont réussi ce débarquement alors qu’étaient proches les flottes américaines et anglaises, en novembre 1942, et alors qu’ils avaient d’autres priorités sur le front de l’Est. Quand bien même ce débarquement eut présenté des difficultés qu’ils eussent voulu contourner, il leur suffisait de faire, dès juillet 1940, ce qu’ils ont fait en février 41 pour soutenir l’Italie, à savoir débarquer quelques divisions à Tripoli. De là, ils pouvaient rapidement gagner la Tunisie et la conquérir (elle aurait fait l’objet d’un « don » à l’Italie qui n’avait cessé de la revendiquer depuis 1936). La question du ravitaillement de leurs troupes aurait été considérablement simplifiée, puisque Malte tenue par les Anglais se trouvait sur la route Sicile – Libye mais pas sur la route Sicile – Tunisie.

En outre le contrôle de la Tunisie et de la Libye aurait tellement isolé Malte que sa conquête serait devenue possible, bien que sans doute coûteuse. Avec cinq ou six divisions, les Allemands auraient pu, de Tunis conquérir l’Algérie jusqu’à la frontière du Maroc espagnol sans grandes difficultés. La flotte française n’aurait eu comme possibilité d’échapper à la destruction, compte tenu de l’impossibilité pour les forces aériennes françaises en A.F.N. de la protéger, que de se replier vers Dakar. Compte tenu de l’étirement des lignes de communication des Allemands, il est bien possible que le Maroc aurait représenté le point ultime de leur expansion à l’Ouest de l’Afrique. L’A.O.F. et l’A.E.F. serait restés à la France résistante, avec l’appui de la flotte britannique, d’une partie de son aviation, et aussi sans doute avec un gros appui matériel américain, sinon un appui directement militaire impliquant la belligérance. Mais cet appui n’aurait pas été instantané compte tenu des délais de la montée en charge de l’industrie américaine (plutôt 1941 que 1940).

À partir de la conquête du Maroc français, la position britannique de Gibraltar aurait été isolée. Elle serait restée tenable si l’Espagne était restée neutre mais facilement neutralisée par l’aviation allemande. Quant à l’Espagne justement, qu’aurait-elle fait ? Franco était très prudent mais l’Allemagne installée militairement au Maroc, grande aurait été sa tentation d’entrer en guerre du côté de l’Axe, avec comme condition l’acquisition par l’Espagne du Maroc français. En tout cas, même restée neutre, l’Espagne aurait dû (comment les refuser sans le risque que l’Allemagne fomente un coup d’État à Madrid, appuyé sur les plus pro-allemands des phalangistes ?) accorder des facilités militaires à l’Allemagne et peut-être le passage vers Gibraltar (via Perpignan ou tout simplement via le Maroc espagnol) pour son démantèlement comme base anglaise. En tout état de cause, l’Allemagne aurait pu disposer de bases navales utiles pour ses sous-marins sur la côte Atlantique du Maroc.

Et pendant ce temps-là en Égypte ? Il n’y a pas de raison de changer quelque chose à l’histoire réelle ici, à savoir que les Anglais, supérieurs aux Italiens en organisation, en matériel, voire en moral des troupes auraient mis en difficulté les troupes de Mussolini, d’autant plus que une fois les Allemands engagés contre la France en Afrique du Nord, l’enjeu de celle-ci aurait été plus fort encore et que les Anglais auraient été sans doute offensifs en Libye et d’abord en Cyrénaïque pour soulager le mieux possible les Français face à l’attaque allemande en Tunisie et en Algérie. Mais là encore, il eut suffit de quelques divisions (l’Africa Korps n’en avait que trois début 41) pour arrêter les Anglais, voire pour les rejeter sur le canal de Suez. Et dans la réalité, rappelons que la contre-offensive anglaise face aux Italiens n’intervient qu’en décembre 1940. Mettons que six divisions eussent été nécessaires pour, dès le dernier trimestre 1940, conquérir l’Égypte et lui donner une indépendance confiée bien sûr à des pro-allemands. Nous sommes à six divisions allemandes donc en Afrique du Nord à l’Est, et autant à l’Ouest, voire dix divisions à l’Ouest (face aux Français). Ce n’était pas au-dessus des moyens des Allemands.

Dans ces conditions, que pouvait-il advenir de Malte ?

Malte, loin de toute position alliée après une poussée allemande sauvant la Cyrénaïque des Anglais – au minimum – voire conquérant l’Égypte, et à l’Ouest, après la conquête allemande de la Tunisie et de l’Algérie, Malte, bien que solidement défendue, pouvait être conquise, comme l’a été la Crête dans des conditions plus difficiles, car la Crête était à proximité de l’Égypte où se trouvait les forces aériennes et navales britanniques. Une fois l’Égypte conquise et là encore quelles que soient les qualités militaires des Anglais, ils n’étaient pas en position de faire face à six divisions allemandes et à une forte aviation (qui bien entendu n’aurait pas été engagée dans une inutile bataille d’Angleterre), les Allemands pouvaient avancer vers la Palestine et conquérir la Syrie. Ils se trouvaient alors à proximité de l’Irak et de ses activistes indépendantistes et pro-allemands (voir la tentative de Rachid Ali en avril 1941) et pouvaient les soutenir. En complément, ils isolaient Chypre et pouvaient y débarquer (là encore peut-on douter de leur capacité à ce genre d’opération quand on voit, dans un contexte très dégradé pour eux, leur conquête-éclair du Dodécanèse en octobre-novembre 43 ?). C’est alors toute la Méditerranée orientale qui eut été entre les mains des Allemands ainsi que la Méditerranée occidentale si l’Algérie avait aussi été conquise (et comment aurait elle pu ne pas l’être compte tenu de la faiblesse des Français en A.F.N., non ravitaillés par la Métropole ?)

Les Allemands pouvaient aussi, après ou en même temps, avec trois ou quatre divisions supplémentaires (il faut tenir compte des forces d’occupation et de contrôle des territoires déjà occupés même si les populations y auraient été plutôt pro-allemandes) descendre la vallée du Nil, prendre Khartoum et Port-Soudan et ainsi, en établissant la liaison avec l’Afrique orientale italienne, empêcher sa conquête par les Britanniques qui a commencé en mars 1941. Le premier problème des Allemands aurait été le manque de camions, mais ils auraient pu réquisitionner tous les camions français sans entraves en l’absence d’armistice.

Une chronologie uchronienne

• 30 juin 1940 : fin de l’occupation de toute la France métropolitaine.

• 7 juillet : occupation de la Corse à partir de l’Italie et de Nice.

• 1er août : débarquement à Tunis (à partir du sud de l’Italie) avec l’appui des Italiens ou débarquement à Tripoli de cinq ou six divisions allemandes marchant vers Tunis.

• 10 août : jonction avec les Italiens de Tripolitaine dans l’hypothèse de débarquement direct à Tunis ou prise de Tunis dans l’autre cas.

• 15 août : prise du port de Bône.

• 20 août : prise d’Alger.

• 25 août : prise d’Oran et de Mers El-Kebir.

• 27 août : arrivée à la frontière du Maroc espagnol.

• 1er septembre : prise de Fès au Maroc.

• 5 septembre : prise de Rabat et de Casablanca.

On peut supposer au mieux que les Français réussissent à résister au sud du Maroc, vers Marrakech. L’armée et surtout l’aviation allemande atteint ses limites logistiques, pour l’instant les Allemands ne poussent pas plus loin.

• 6 septembre : début de l’offensive allemande pour la conquête de l’Égypte.

• 20 septembre : prise du Caire.

• 30 septembre : achèvement de la conquête de l’Égypte.

• 30 octobre : attaque du Soudan.

• 25 novembre : jonction avec les Italiens d’Érythrée et d’Éthiopie. Installation de bases de sous-marins dans l’océan Indien, notamment en Somalie.

Un tel scénario eut nécessité quelques vingt-cinq divisions engagées hors d’Europe. L’effort n’impliquait donc nullement de dégarnir le continent européen. Mais, par contre, il eut amené un changement complet de vision et eut nécessité même ce changement de vision. Il s’agissait alors de rompre avec les ambitions néo-coloniales en Europe même : espace vital au détriment des Russes et des Ukrainiens, réduction des Slaves en esclavage. À l’inverse, cela eut été l’adoption d’une véritable politique mondiale. Objectif : non pas la conquête totale du monde, mais un contrepoids réel aux puissances thalassocratiques. Non pas s’enfermer dans une forteresse Europe mais lui donner de l’air par des débouchés vers les grands océans (Maroc pour l’Atlantique, Somalie pour l’océan Indien, voire Madagascar plus tard…), liaisons avec le Japon, contrôle complet de la Méditerranée et éviction de la Grande-Bretagne de ce grand lac où elle n’a rien à faire du point de vue continental européen, politique pro-arabe et post-coloniale de transition des peuples vers l’indépendance dans la coopération avec l’Europe.

Au-delà des perspectives ouvertes par cette histoire virtuelle, il reste une quasi-certitude : l’Allemagne a beaucoup perdu à l’Armistice de juin 40, elle s’est enfermée dans une victoire strictement continentale en s’interdisant une politique réellement mondiale, anticipant sur les risques futurs d’entrée en guerre des États-Unis en prenant des gages en Afrique du Nord, au Moyen-Orient, vers la Mésopotamie, et jusqu’au Soudan et l’océan Indien. Quelle chance pour l’Allemagne si… la France avait voulu continuer la guerre en 1940 !

Noël Rivière

Article printed from Europe Maxima: http://www.europemaxima.com

URL to article: http://www.europemaxima.com/?p=1948

15:17 Publié dans Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (3) | Tags : histoire, uchronie, juin 1940, seconde guerre mondiale, deuxième guerre mondiale |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 05 juin 2011

The Fascist Past of Scotland

The Fascist Past of Scotland

Ex: http://xtremerightcorporate.blogspot.com/

Today, Scottish nationalism is associated mostly with the left. Traditional, conservative nationalism such as produced the Jacobite wars was long in going but seems gone for good at this point. However, Scottish fascists have long been involved in the troubled life of what goes under the blanket-term of ‘British fascism’. Nonetheless, it is important to note the history of nationalism in modern Scotland, which of course existed when Scotland was an independent nation but which survived after the union with England and was never seen in a more pure form than in the Jacobite uprisings that are so famous. Although not often considered, the Jacobite restoration efforts were actually very corporatist at heart. Just to refresh, at its core, corporatism is nothing more than the organization of society based on corporate bodies and the use of those corporate bodies in exercising power for the nation as a whole. This was, in a real sense, what the Jacobite risings were all about and in a very traditional way, upholding the ancient values of western civilization.

In modern times, however, liberalism began to creep in and ever since as far back as the 1830’s Scotland has tended to be dominated by the leftist party (Whig, Labour, etc). In 1934 the Scottish National Party was founded, bent on the division of Great Britain and at least some degree of independence for Scotland. Socialist parties also sprang up. These, of course, had an influence on what was considered far-right politics as it would anywhere else but nonetheless, those Scots labeled as “fascists” tended almost to a man to support the union, the British Empire and British power and greatness, seeing the nations of the British Isles as stronger together than apart. Of course the most famous such organization was the British Union of Fascists and there were a number of prominent Scots aligned with or associated with that movement, and a few should be mentioned.

Less colorful than Hay, but probably an even more staunch fascist Scotsman was Robert Forgan. The son of a minister in the Church of Scotland, he was educated in Aberdeen, became a doctor and served in World War I, later becoming an STD expert. While working in Glasgow he became a socialist, out of concern for the urban poor of course, and also entered politics as a member of the Independent Labor Party. He supported the very socialistic “Mosley Memorandum” which resulted in his break with mainstream leftists and his formation of the New Party. Mosley and Forgan were almost inseparable. He was one of the most successful politicians of the New Party, a key player in organizing and fleshing out the movement and even stood as godfather to Mosley’s son Michael. He was less visible but no less important when Mosley dropped the New Party idea and went on, instead, to found the British Union of Fascists. It was Forgan who worked behind the scenes to enlist more legitimate, acceptable supporters for the BUF, obtain funding for the movement and he was largely responsible to setting up the January Club.

00:05 Publié dans Histoire, Terres d'Europe | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : terres d'europe, ecosse, grande-bretagne, patries charnelles, fascisme, histoire, iles britanniques, europe, affaires européennes |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 04 juin 2011

La rivolta di Maritz e De Wet nel 1914

La rivolta di Maritz e De Wet nel 1914, preannuncio della rivincita boera sull’Inghilterra

La Repubblica Sudafricana, come è noto, era uscita dal Commonwealth britannico nel 1949 e vi è stata riammessa solo nel 1994, dopo che era stato rimosso l’oggetto del contendere, ossia dopo che fu smantellata la legislazione sull’Apartheid.

La Repubblica Sudafricana, come è noto, era uscita dal Commonwealth britannico nel 1949 e vi è stata riammessa solo nel 1994, dopo che era stato rimosso l’oggetto del contendere, ossia dopo che fu smantellata la legislazione sull’Apartheid.

A volere fortemente la politica della “separazione” fra bianchi e neri era stata la componente di origine boera della comunità europea, insediatasi al Capo di Buona Speranza nel XVII secolo e poi, durante le guerre napoleoniche (1797), respinta verso l’interno dagli Inglesi, ove, nel XIX secolo, aveva dato vita alle due fiere Repubbliche indipendenti del Transvaal e dell’Orange.

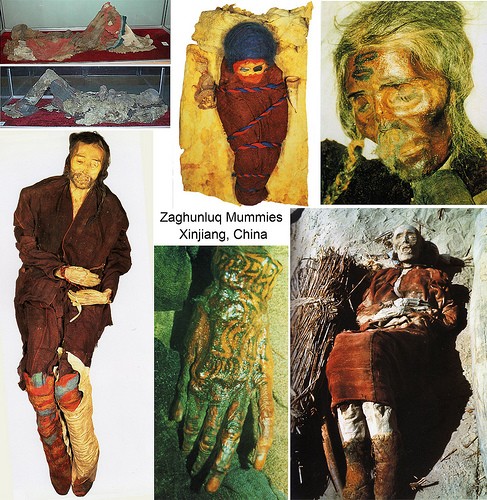

Poiché la Grande Migrazione dei Boeri al di là del fiume Orange, o Grande Trek, come è nota nei libri di storia sudafricani, ebbe luogo all’incirca nella stessa epoca in cui, da settentrione, giunsero le tribù bantu che, originarie della regione dei laghi dell’Africa orientale, a loro volta respingevano Boscimani e Ottentotti, i Boeri e, in generale, i bianchi sudafricani hanno sempre negato validità all’affermazione secondo cui, nel loro Paese, una minoranza bianca si sarebbe imposta su di una maggioranza nera, sostenendo, al contrario, che essi avevano raggiunto e colonizzato le regioni dell’interno prima dei Bantu, e non dopo.

Sia come sia, i Boeri sostennero due guerre contro l’imperialismo britannico: una, vittoriosa, nel 1880-81, ed una, assai più dura, nel 1899-1902, terminata con la piena sconfitta della pur coraggiosa resistenza boera, guidata dal leggendario presidente Krüger. Il conflitto era stato reso inevitabile non solo dai grandiosi progetti espansionistici dell’imperialismo inglese, impersonato in Africa da uomini come il finanziere Cecil Rhodes e dal celebre slogan “dal Cairo al Capo” (di Buona Speranza), ma anche e soprattutto dalla scoperta di ricchi giacimenti auriferi e di miniere di diamanti nel territorio delle due Repubbliche boere.

Non fu, quest’ultima, una vittoria di cui l’immenso Impero Britannico poté andar fiero: esso riuscì a piegare la resistenza di quel piccolo e tenace popolo di contadini-allevatori solo dopo che ebbe messo in campo tutte le risorse umane, materiali e finanziarie di cui poteva disporre nei cinque continenti e solo dopo che i suoi comandanti ebbero fatto ricorso alla tattica della terra bruciata, distruggendo fattorie e raccolti, e soprattutto trasferendo ed internando la popolazione boera nei campi di concentramento, ove a migliaia morirono di stenti e di malattie.

È pur vero che la pace, firmata a Pretoria il 31 maggio 1902, ed il successivo trattato di Veereniging, che sanciva la sovranità britannica sulle due Repubbliche, accordarono ai vinti delle condizioni relativamente miti, se non addirittura generose. In particolare, il governo inglese si accollò l’onere del debito di guerra contratto dal governo del presidente Krüger, che ammontava alla bellezza di 3 milioni di lire dell’epoca, ed accordò uno statuto giuridico speciale alla lingua neerlandese, non riconoscendo ancora la specificità della lingua afrikaans.

È degno di rilievo il fatto che nel trattato di stabiliva esplicitamente la clausola che ai neri non sarebbe stato concesso il diritto di voto, ad eccezione di quelli residenti nella Colonia del Capo, in cui i coloni inglesi costituivano la maggioranza bianca; perché, nell’Orange e nel Transvaal, i Boeri non avrebbero mai accettato una eventualità del genere, e sia pure in prospettiva futura.

È degno di rilievo il fatto che nel trattato di stabiliva esplicitamente la clausola che ai neri non sarebbe stato concesso il diritto di voto, ad eccezione di quelli residenti nella Colonia del Capo, in cui i coloni inglesi costituivano la maggioranza bianca; perché, nell’Orange e nel Transvaal, i Boeri non avrebbero mai accettato una eventualità del genere, e sia pure in prospettiva futura.

L’intenzione del governo britannico era quella di integrare progressivamente i Boeri nella propria cultura, a cominciare dall’educazione e dalla lingua; ma il progetto di anglicizzare i Boeri attraverso la scuola si rivelò fallimentare e nel 1906, con l’avvento al governo di Londra del Partito Liberale, esso venne abbandonato. Non solo: le autorità britanniche dovettero riconoscere l’afrikaans come lingua distinta dal neerlandese e questo rappresentò un primo passo verso il rovesciamento dei rapporti di forza, all’interno della comunità bianca sudafricana, tra i coloni di origine britannica e quelli di origine boera.

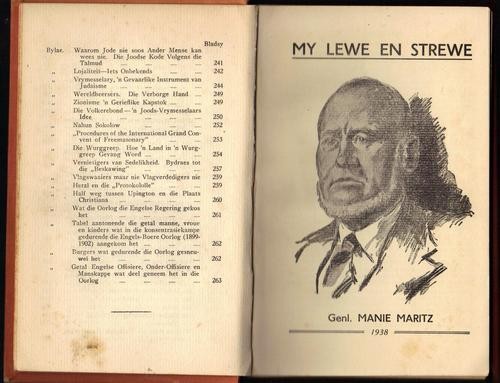

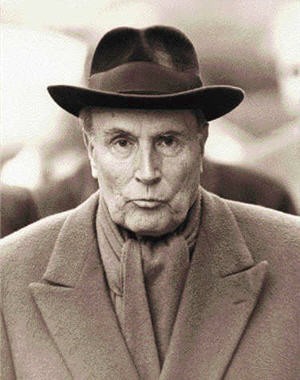

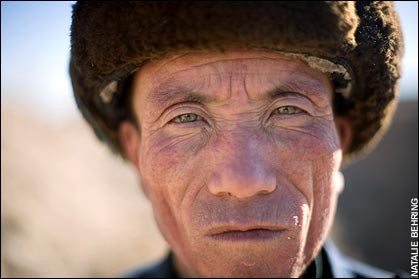

Picture: Manie Maritz

Un altro passo fu la nascita, il 31 maggio 1910, dell’Unione Sudafricana, grazie alla riunione delle quattro colonie del Capo, del Natal, dell’Orange e del Transvaal: a soli otto anni dalla conclusione di una guerra straordinariamente sanguinosa e crudele, caratterizzata da pratiche inumane tipicamente “moderne”, quali la distruzione dei raccolti, il trasferimento forzato di intere popolazioni ed il loro internamento in veri e propri lager, il Sudafrica diventava un Dominion autonomo nell’ambito dell’Impero britannico, con una maggioranza afrikaner; processo che sarebbe culminato nel 1931 con la conquista della piena indipendenza, votata dal Parlamento di Londra con il cosiddetto Statuto di Westminster.

Un episodio poco noto al pubblico occidentale è quello della rivolta anti-britannica scoppiata nell’Unione Sudafricana nel 1914, sotto la guida dei generali boeri Manie Maritz e De Wet, in coincidenza con lo scoppio della prima guerra mondiale, cui l’Unione medesima partecipò al fianco della Gran Bretagna, soprattutto per il deciso appoggio dato alla causa britannica da uomini prestigiosi della comunità afrikaner come Louis Botha e Jan Smuts.

In effetti, non tutte le ferite dell’ultimo conflitto erano state sanate e una parte della popolazione afrikaner, animata da forti sentimenti nazionalisti, non immemore della simpatia (sia pure solamente verbale) mostrata dal kaiser Wilhelm II Hohenzollern per la causa boera, ritenne giunto il momento della riscossa e si dissociò dal governo di Pretoria, invocando, anzi, la lotta aperta contro gli Inglesi al fianco della Germania.

Al di là del corso inferiore dell’Orange, dal 1884, si era costituita la colonia tedesca dell’Africa Sudoccidentale (oggi Namibia) e i capi afrikaner insorti speravano che da lì – o, più verosimilmente, da una rapida vittoria degli eserciti tedeschi in Europa – sarebbero giunti gli aiuti necessari per sconfiggere le forze britanniche e per rialzare la bandiera dell’indipendenza boera sulle terre dell’Orange e del Transvaal.

Così ha rievocato quella vicenda lo storico francese Bernard Lugan, “Maître de Conferences” all’Università di Lione III, specialista di storia dell’Africa e per dieci anni professore all’Università del Ruanda, nel suo libro Storia del Sudafrica dall’antichità a oggi (titolo originale: Histoire de l’Afrique du Sud de l’Antiquité a nos jours, Paris, Librairie Académique Perrin, 1986; traduzione italiana di L. A. Martinelli, Milano, Garzanti, 1989, pp. 195-99):

«Quando, il 4 agosto 1914, scoppi la guerra, l’Unione Sudafricana si trovò automaticamente impegnata, in quanto Dominion britannico, a fianco degli Inglesi, ossia nel campo dell’Intesa. Ne risentì immediatamente la coesione fra le due componenti bianche della popolazione. Gli anglofoni accettarono l’entrata in guerra come un dovere verso la madrepatria, mentre gli Afrikaner si divisero in due gruppi: il primo, uniformandosi alle vedute di Botha e di Smuts, proclamò la propria solidarietà con la Gran Bretagna, il secondo, con alla testa Hertzog, propose che l’Unione rimanesse neutrale fino a quando non avesse a subire un attacco diretto. Il fondatore del Partito nazionalista rifiutava ogni obbligo diretto, ed affermava il diritto del Sudafrica di decidere liberamente, in situazioni drammatiche come quella presente. Quando, nel settembre 1914, il Parlamento di Città del Capo accolse la richiesta di Londra di arruolare nell’Unione un corpo militare per l’occupazione dell’Africa sud-occidentale tedesca, in una larga parte dell’opinione pubblica afrikaner le reazioni furono violente. Scoppiò un’insurrezione, capeggiata dagli antichi generali boeri Manie Maritz e De Wet, che si diffuse rapidamente fra gli ufficiali superiori dell’esercito sudafricano: dodicimila uomini, per lo più originari dell’Orange, presero le armi contro il loro governo. Sembrava imminente una guerra civile fra Afrikaner, e il rischio era grande perché i ribelli avevano proclamato la Repubblica sudafricana:

“PROCLAMA

DELLA RESTAURAZINE

DELLA REPUBBLICA SUDAFRICANA

Al popolo del Sudafrica:

Il giorno della liberazione è giunto. Il popolo boero del Sudafrica è già insorto ed ha iniziato la guerra contro

LA DOMINAZIONE BRITANNICA, DETESTATA ED IMPOSTA.

Le truppe della Nuova Repubblica Sudafricana hanno già ingaggiato la lotta contro le truppe governative britanniche.

Il governo della Repubblica Sudafricana è provvisoriamente rappresentato dai signori

Generale MARITZ

maggiore DE VILLIERS

maggiore JAN DE WAAL-CALVINIA

Il Governo restituirà al popolo sudafricano l’indipendenza che l’Inghilterra gli ha sottratto dodici anni or sono.

Cittadini, compatrioti, voi tutti che desiderate vedere libero il Sudafrica,

NON MANCATE DI COMPIRE IL VOSTRO DOVERE VERSO L’AMATA

E BELLA BANDIERA “VIERKLEUR”!

Unitevi sino all’ultimo uomo per ristabilire la vostra libertà e il vostro diritto!

IL GOVERNO GERMANICO,LA CUI VITTORIA È GIÀ SICURA, HA PER PRIMO RICONOSCIUTO ALLA REPUBBLICA SUDAFRICANA IL DIRITTO DI ESISTERE, ed ha con ciò stesso mostrato di non avere alcuna intenzione di intraprendere la conquista del Sudafrica come hanno preteso i signori Botha e Smuts al Parlamento dell’Unione.

Kakamas, Repubblica Sudafricana, ottobre 1914.

IL GOVERNO DELLA REPUBBLICA SUDAFRICANA

(Firmato) MARITZ, DE VILLIERS, JAN DE WAAL”.

Botha decise di proclamare la legge marziale il 12 ottobre, due giorni dopo che Maritz, alla testa di un reggimento sudafricano, aveva disertato per raggiungere le truppe germaniche proclamando la propria intenzione di invadere la provincia del Capo. I sostenitori più irriducibili della causa boera giudicavano la Germania capace di infliggere all’Inghilterra una sconfitta definitiva, e che quindi si presentasse loro un’occasione unica per prendersi la rivincita sui vincitori del 1902, e restituire il Sudafrica agli Afrikaner. Ma il movimento fu disordinato: i “kommando”, organizzati frettolosamente, male armati, malvisti da una parte della popolazione che aveva appena finito di medicare le ferite del 1899-1902, non furono in grado di affrontare le unità dell’esercito regolare. Gli ultimi ribelli si arresero il 2 febbraio 1915.

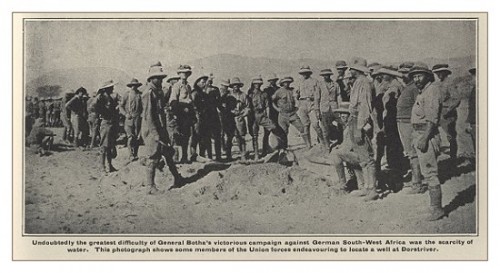

Poté così cominciare la campagna contro l’Africa sud-occidentale tedesca. Londra aveva fatto sapere che essa sarebbe stata considerata come un servizio reso all’Impero, e di conseguenza l’Impero ne avrebbe tratto dei vantaggi politici al momento del trattato di pace.

La sproporzione delle forze era tale che i Tedeschi non potevano far altro che cercar di ritardare una sconfitta inevitabile. Disponevano di 1.600 effettivi, rinforzati da 6.000 riservisti mobilitabili su di una popolazione bianca di 6.000 persone. Il colonnello Heydebreck non poté impedire la manovra sudafricana: Botha sbarcò a Swakompund cin 12.000 uomini, Smuts a Lüderitz con 6.000, ed oltre 30.000 uomini passarono il fiume Orange. Il 5 maggio 1915 venne occupata Windhoek, la capitale della colonia tedesca; una sporadica resistenza continuò ancora, favorita dalla vastità della steppa, fino al 9 luglio 1915, quando ad Otavi fu sottoscritta la resa delle truppe del Reich. La campagna era stata breve e le perdite umane limitate: con essa Botha diede all’Unione il protettorato sull’Africa sud-occidentale.

Alle elezioni generali dell’ottobre 1915 Botha dovette affrontare l’opposizione sempre più forte del Partito nazionale di Hertzog. I nazionalisti afrikaner respingevano nuove forme di partecipazione del Sudafrica alla guerra, e in particolare si opponevano all’invio di contingenti in Africa orientale. Per esprimere e difendere gli interessi afrikaner durante la campagna elettorale il Partito nazionale diede vita a un proprio giornale, “Die Burger”.

Botha conservò la maggioranza in Parlamento con 54 seggi, ai quali si aggiunsero i 40 seggi ottenuti dagli Unionisti che appoggiavano la politica militare del primo ministro. Tuttavia il Partito nazionale, con 27 seggi, poté far sentire la propria voce: da quel momento si sarebbero dovuti fare i conti anche con esso.

Nel 1916 fu inviato in Tanganica un corpo di 15.000 Sudafricani in rinforzo al’armata inglese che, quantunque numerosa, non riusciva ad aver ragione delle truppe tedesche del generale Lettow-Vorbeck. Nell’agosto del 1914 quest’ultimo – allora colonnello – aveva a disposizione aveva a disposizione solo 3.000 europei e 16.000 ascari per la difesa dell’intera Africa orientale tedesca: ma con queste scarsissime forze e senza ricevere rifornimenti alla madrepatria resistette fino al novembre 1918 ad oltre 250.000 soldati britannici, belgi, sudafricani e portoghesi. Nella guerra di imboscate con la quale Alleati e Tedeschi si affrontarono nel Tanganica meridionale, il contingente sudafricano, comandato prima del generale Smuts e in seguito dal generale Van Deventer, ebbe una parte di primo piano.

La 1a Brigata sudafricana sbarcò a Marsiglia il 15 aprile 1916. Incorporata nella 9a Divisione scozzese fu inviata nel giugno sul fronte della Somme, ove fra il 14 e il 19 giugno i volontari si distinsero nei combattimenti del bosco di Delville, mantenendo le loro posizioni a prezzo di fortissime perdite: 121 ufficiali su 126 e 3.032 soldati su 3.782. Ricostituita con l’arrivo di altri volontari, la brigata prese parte nel 1917 alla battaglia di Vimy e di Ypres, e nel 1918 alla battaglia di Amiens, nel corso della quale perdette 1.300 uomini su 1.800 impegnati nel combattimento. Fu ricostituita per la terza volta e poté partecipare alle ultime fasi della guerra.

In complesso l’Unione Sudafricana fornì agli Alleati un contingente di 200.000 uomini, dei quali 12.452 caddero in guerra. Sempre più numerosi divennero gli Afrikaner che non vollero più esere chiamati obbligatoriamente a combattere per la Gran Bretagna, ben decisi a conquistarsi un autonomia maggiore e magari una totale indipendenza. Su questo punto Hertzog non ottenne a Versailles alcuna soddisfazione, perché gli Alleati confermarono la situazione esistente pur offrendo all’Unione un mandato sull’Africa sud-occidentale».

Paradossalmente, proprio la presenza di un protettorato germanico sulla sponda settentrionale del fiume Orange, ai confini della Provincia del Capo, aveva svolto una funzione importante nel rafforzare i legami fra l’Unione Sudafricana e la madrepatria britannica, dal momento che la componente inglese della popolazione bianca sudafricana aveva vissuto con disagio quella vicinanza, se non con un vero e proprio senso di pericolo.

Nel 1878, la Colonia del Capo aveva ottenuto da Londra un tiepido consenso ad occupare la Baia della Balena, enclave strategica in quella che ancora non era la colonia tedesca dell’Africa sud-occidentale; ma quando, nel 1884, quasi da un giorno all’altro, il cancelliere Bismarck aveva proclamato il protettorato del Reich, cogliendo del tutto alla sprovvista il Foreign Office, quella sensazione di minaccia si era concretizzata quasi dal nulla e certamente svolse un ruolo importante nel rinsaldare il legame di fedeltà del Dominion con l’Inghilterra, prima e durante la guerra mondiale del 1914-18.

Una situazione analoga si era verificata, in quegli stessi anni, con il Dominion dell’Australia (e, in minor misura, della Nuova Zelanda): la presenza tedesca nell’Oceano Pacifico, specialmente nella Nuova Guinea nord-orientale, nell’Arcipelago di Bismarck e nelle isole Marshall, Marianne, Palau e Caroline, oltre che in una parte delle Samoa, abilmente sfruttata dalla propaganda inglese, generò una sorta di psicosi nell’opinione pubblica australiana che, in cerca di protezione da una possibile minaccia germanica, fu spinta a cercare nel rafforzamento dei legami morali e ideali con la madrepatria uno scudo contro i Tedeschi (la stessa cosa si sarebbe ripetuta nel 1941, questa volta nei confronti della minaccia giapponese, ben più concreta e immediata).

Per quel che riguarda la rivolta boera di Maritz e De Wet, il suo rapido fallimento fu dovuto alla scarsa adesione della popolazione boera: scarsa adesione che fu l’effetto non già di un sentimento di solidarietà o di una problematica “riconoscenza” verso la Gran Bretagna, entrambe impossibili e per varie ragioni, quanto piuttosto, come evidenzia Bernard Lugan, per la stanchezza dovuta alla prova durissima del 1899-1902 e per il desiderio di non riaprire troppo presto quelle ferite e di non mettere a repentaglio, e in circostanze a dir poco incerte, quei margini di autonomia che, bene o male, il governo inglese a aveva riconosciuto ai Boeri.

Si trattava, come abbiamo visto, di margini di autonomia che essi, specie attraverso l’azione politica dei nazionalisti di Hertzog e Malan, erano decisi ad allargare per via pacifica, ma con estrema determinazione, fino alle ultime conseguenze, stando però attenti a giocare bene le loro carte e a non esporsi, con una mossa imprudente, ad una nuova sconfitta, con tutti gli effetti politici negativi che ciò avrebbe inevitabilmente comportato.

Si trattava, come abbiamo visto, di margini di autonomia che essi, specie attraverso l’azione politica dei nazionalisti di Hertzog e Malan, erano decisi ad allargare per via pacifica, ma con estrema determinazione, fino alle ultime conseguenze, stando però attenti a giocare bene le loro carte e a non esporsi, con una mossa imprudente, ad una nuova sconfitta, con tutti gli effetti politici negativi che ciò avrebbe inevitabilmente comportato.

In questo senso, il fatto che solo con estrema fatica, e solo dopo due anni dall’inizio della guerra, l’Unione Sudafricana accettasse di inviare un consistente corpo di spedizione contro l’Africa Orientale Tedesca (la breve campagna contro l’Africa Sud-occidentale tedesca del 1915 era stata solo il naturale corollario del fallimento della rivolta boera); e che, nel 1917-18, una sola brigata venisse inviata a combattere fuori del continente africano, mentre forze canadesi, australiane e neozelandesi ben più consistenti stavano combattendo o avevano già combattuto al fianco della Gran Bretagna, in Europa e nel Medio Oriente (campagna di Gallipoli), sta a testimoniare quanto poco l’opinione pubblica sudafricana fosse giudicata “sicura” all’interno del sistema imperiale e quanto poco affidabili le truppe sudafricane, soprattutto boere, in una campagna militare che si svolgesse lontano dai confini dell’Unione e che, quindi, non presentasse un carattere chiaramente difensivo.

Anche il “mandato” sulla ex Africa Sud-occidentale tedesca, in effetti, si deve leggere soprattutto come un palliativo ideato dal governo di Londra che, tramite i suoi buoni uffici presso la Società delle Nazioni, intendeva dare un contentino al nazionalismo afrikaner, sempre illudendosi di poter allontanare la resa dei conti con il partito di Hertzog e Malan e la perdita di ogni effettiva sovranità sul Sudafrica e sulle sue immense ricchezze minerarie.

Si trattò, invece, di un calcolo miope, che non servì a distrarre l’attenzione dei nazionalisti afrikaner dal perseguimento della piena indipendenza e che, viceversa, creò i presupposti per una ulteriore complicazione internazionale: perché, come è noto, il governo sudafricano considerò il mandato sull’Africa Sud-occidentale come una semplice finzione giuridica e il Parlamento sudafricano legiferò nel senso di una vera e propria annessione di quel territorio e non certo nella prospettiva di avviarlo all’indipendenza.

Non bisogna mai dimenticare che l’Impero britannico, nel 1914, comprendeva un quarto delle terre emerse e un complesso di territori, come l’India, abitati da centinaia di milioni di persone, con ricchezze materiali incalcolabili. Lo storico del Novecento e, in particolare, lo storico delle due guerre mondiali, non dovrebbe mai prescindere dalla ferma, tenace volontà dei governi inglesi, specialmente conservatori, di difendere in ogni modo quell’immenso patrimonio, nella convinzione di poter trovare la formula politica per allentare, forse, la stretta, ma di conservare la sostanza di quella situazione, estremamente invidiabile per la madrepatria.

I governanti britannici erano talmente convinti di poter riuscire nell’impresa che perfino Churchill, firmando, nel 1941, la Carta Atlantica insieme a Roosevelt, nella quale si sanciva il solenne impegno anglo-americano in favore della libertà e dell’autodecisione dei popoli, era lontanissimo dal supporre che solo sei anni dopo l’Inghilterra avrebbe dovuto riconoscere l’indipendenza dell’India e del Pakistan, cuore e vanto di quell’Impero.

Essi temevano l’effetto domino di qualunque rinuncia coloniale sul resto dell’Impero ed è per questo che repressero con tanta ferocia l’insurrezione di Pasqua del 1916, a Dublino, salvo poi concedere all’Irlanda, ma solo a guerra finita, una indipendenza mutilata, conservando quell’Ulster in cui, fra nazionalisti protestanti e indipendentisti cattolici, si sarebbero riprodotte, ma a parti rovesciate, le stesse dinamiche distruttive del Sudafrica, diviso fra bianchi di origine inglese e bianchi di origine boera, dopo la vittoria militare inglese del 1902.

La storia ci mostra che non sempre chi vince sul piano militare vince anche, nel medio e nel lungo periodo, sul piano politico.

Tale fu anche il caso del Sudafrica, dopo la conquista britannica del 1902; e, in questo senso, anche la fallita insurrezione boera del 1914, forse, deve essere valutata più come il primo annuncio della futura indipendenza del Sudafrica dall’Inghilterra, che come l’ultimo sussulto della precedente guerra anglo-boera.

Francesco Lamendola

00:05 Publié dans Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : histoire, histoire africaine, afrique du sud, boers, afrique, affaires africaines |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

South African Nationalist Manie Maritz

South African Nationalist Manie Maritz

Ex: http://xtremerightcorporate.blogspot.com/

The British themselves were rather worried about how the Boers would respond to the outbreak of war with Germany and with good reason. Of the three preeminent Boer leaders from the freedom wars; Louis Botha, Christiaan De Wet and Jacobus Hercules (Koos) De la Rey only Botha was considered reliably loyal to the British. Many Afrikaners took divergent positions based on different motives but a sizeable minority at least were not prepared to fight against a nation that had sympathized with them in their own struggle for freedom in the service of those who had conquered them. The First World War was their opportunity to take revenge and the Germans counted on this, stockpiling a great deal of weapons and ammunition to equip the rebel Boer army they hoped would soon emerge. The Germans had been spreading the word for some time that with their help the Boers could drive out the British and establish a greater empire for themselves in Africa more to their own liking. As war erupted in Europe both sides began to form up in South Africa.

Louis Botha, newly elected Prime Minister of the Union of South Africa, pledged his loyalty to the British Empire and agreed with London to launch the conquest of German Southwest Africa which many Boers opposed. Christiaan De Wet was advocating opposition to Britain and alliance with Germany and General Koos De la Rey, who was believed to be on the side of rebellion, was gunned down by British police before his influence could have effect. Likewise, Christiaan Frederik Beyers, commandant-general of the Union of South Africa Defense Force, resigned his position to join the rebel faction as did General Jap Christoffel Greyling Kemp who was in charge of the training post at Potchefstroom. However, the most dangerous of them all was Colonel Salomon Gerhardus (Manie) Maritz who was to have been on the front lines of the invasion of German territory. Maritz was sent orders to report to Pretoria in the hopes of neutralizing him but he smelled the trap and ignored the order. War might have been headed for German Southwest Africa but it was to hit South Africa first.

British intelligence reported that Maritz and his officers were openly speaking of joining the Germans. True enough, Maritz announced his intention to ally with the Germans to his commandos and his allegiance to the provisional rebel government of the former Boer republics. He proclaimed the independence of South Africa, the Orange Free State, Cape Province and Natal and called upon the White population to join him and their German comrades in revolt against the British. It was October, 1914, and Maritz gave his men one minute to decide whether they were on the side of the Boer-German alliance or the British. Most followed their commander but about 60 remained loyal to Britain and were duly handed over to the Germans as prisoners of war. Rallies were held, speeches were given, and passionate appeals on behalf of Afrikaner nationalism were voiced as the rebellion seemed to be catching on. Beyers, De Wet, Maritz, Kemp and Bezuidenhout were chosen to lead the provisional Boer government and newly promoted General Manie Maritz occupied Keimos around Upington which had been his previous area of operations. Fighting broke out in local clashes between rebel and loyalist factions.

On October 26, 1914 the British side made the state of war clear when Louis Botha personally took command of the forces assembling to crush the Boer rebellion. It was the first and so far only time that a British Empire/Commonwealth prime minister led troops into battle while in office. Moreover, this was especially difficult for old Boer soldiers like Botha and Jan Smuts who would be fighting against their own people, many of them their own comrades from the previous wars against the British. However, Botha and Smuts were truly committed to the Allied cause and when Australian troops on their way to Europe were offered to help crush the rebellion Botha refused and preferred to use loyalist Afrikaners to suppress the rebel Afrikaners so as not to exacerbate the Boer-British ethnic tensions which were obviously already running high. Volunteers, reserves, support personnel and the like were all mobilized in this massive effort by the Union government to stamp out the uprising before the Boer rebels spread their influence and forged a coordinating strategy with the Germans which would have been disastrous.

The Boer rebels were busy as well. General De Wet took his Lydenburg commandos and seized Heilbron and captured a British train which provided a wealth of supplies and ammunition. Soon De Wet had 3,000 men under arms while General Beyers mobilized more in the Magaliesberg in addition to those already assembled around Upington under General Maritz. On the loyalist side, Botha took command of 6,000 cavalry and some field guns assembled at Vereeniging in the Transvaal with the aim of destroying De Wet. Martial law was declared and overwhelming government force was brought down on the rebels. General Maritz was defeated on October 24 but escaped into German Southwest Africa where he continued his own resistance. Botha caught General De Wet at a farmhouse in Mushroom Valley and broke the Boer rebels on November 12. General De Wet and a remnant of his men retreated into the unassuming but brutal Kalahari Desert. General Beyers and his commandos met with an initial defeat at Commissioners Drift after which he joined forces with General Kemp. However, they too were beaten and Beyers drowned while trying to escape across the Vaal River. Kemp led the rest of his men to safety in German territory to join up with General Maritz but only after a long and brutal march across the Kalahari. Kemp was eventually captured in 1915 though by his former comrade General Jaap van Deventer after which he served time in prison and went on to become minister of agriculture in 1924.

The potential Boer rebellion had been crushed in its infancy and Prime Minister Botha went ahead with his invasion of German Southwest Africa. On hand to oppose him was Manie Maritz who had no intention of giving up so easily. He was aided by the fact that the Germans had probably the best colonial army in Africa and although hopelessly outnumbered they fought with considerable skill and tenacity. Early German victories hurled the British invasion back and forced Botha to take a more careful approach. He heard of General Maritz again when the rebel Afrikaner took his Boer troops and with German assistance attacked his former base at Upington, inflicting quite a bloody nose before General van Deventer beat them back. The Union troops faced stiff German resistance, harassing artillery fire, poisoned water wells and land mines in their march into the interior of Southwest Africa. The Germans won a number of stunning victories but eventually the strength of British numbers, some 60,000 troops, proved impossible to overcome and German Southwest Africa was conquered. The British also liberated the loyalists Maritz had turned over to the Germans when they took Tsumeb where the Germans had also been keeping their weapons stockpile for the Boer rebellion.

However, the rebellious General Manie Maritz was not to be captured having escaped yet again, this time to the safety of then neutral Portuguese West Africa (Angola). For the rest of the war years he traveled to Portugal itself and later Spain before returning to his native South Africa in 1923. Once back he proved just as troublesome for the British as he ever had and still somewhat attached to Germany as time would tell. In 1936 he organized a South African Nazi type party with typical anti-Semitic rhetoric thrown into the mix. Of course, in reality, Jews were hardly a presence in South Africa, but it was part of an overall Afrikaner nationalist program and to the disgust of the British and pro-Union South Africans he continued his agitation even after the start of World War II. He did not live to see the final defeat of Nazi Germany though as he died in a car wreck on December 19, 1940 in Pretoria. A lifelong Afrikaner nationalist and enemy of Great Britain he certainly regretted nothing. It would be easy to say (and many have) that the entire Maritz rebellion and the German defeat in Namibia were an exercise in futility and a complete waste of time. However, although the Boers remained subject to Britain and the Germans lost what was arguably their most profitable colony, in a way the German and Boer campaigns were a success for the Central Powers in that they delayed considerably the mobilization of South African troops for use against the more formidable German colonial army in German East Africa (which went on a rampage) and they prevented any transfer of South African troops to the western front during the vital battles fought in 1914. That being said, the evaluation of these actions still depends a great deal on the point of view of the observer. To the British and loyalists General Maritz was a traitor of the blackest sort, a collaborator and ranked at the top of the list of enemies of the British Empire. However, General Maritz is still revered by some Afrikaner nationalists for his dogged defiance and by modern day neo-Nazi Boers who think he was on the right side in World War II as well.

00:05 Publié dans anthropologie, Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : afrique, afrique du sud, affaires africaines, histoire africaine, boers |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

jeudi, 02 juin 2011

Lépante et sa signification actuelle

Lépante et sa signification actuelle

par Jean-Gilles MALLIARAKIS

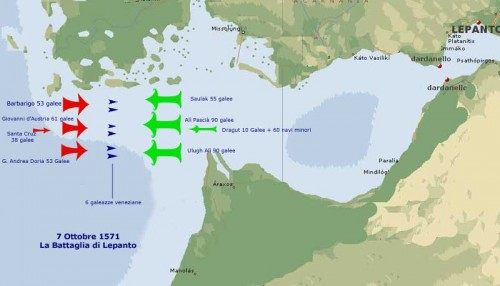

Comme tous les événements historiques, comme tous les anniversaires, la bataille de Lépante peut prêter à des discours extrêmement contradictoires. La victoire navale de la flotte commandée par Don Juan d'Autriche remonte au 7 octobre 1571. Certains commémoreront donc cet automne son 440e anniversaire. Sur le fond, on doit leur donner, par avance, raison. Rien ne se révèle pire que l'oubli, pas même les contresens d'un soir, d'une manifestation ou d'un discours. Oswald Spengler considérait, et il écrivit un jour "qu'au dernier moment c'est toujours un peloton de soldats qui sauve la civilisation". On a bien oublié de nos jours ce représentant de la révolution conservatrice. Et cette conception héroïque disconvient à notre époque où on se préoccupe plus de sécurité alimentaire que de défense des frontières.

Un petit mot quand même sur ce premier défi lancé à l'empire ottoman. Depuis le salutaire coup d'arrêt donné, sur l'Adriatique, par Skanderbeg (1405-1468) au XVe siècle (1), les armées de la Sublime Porte semblaient aux Européens pratiquement invincibles. Si l'on accorde la première place à l'action militaire, on ne peut que saluer cette expédition partie de Messine. Elle infligea une défaite matériellement considérable à la marine turque. Sur une flotte de 300 bâtiments, celle-ci subit la destruction de 50 navires et la capture de 100 par les chrétiens coalisés. 15 000 captifs européens furent libérés. Au nombre des 8 000 blessés occidentaux on doit rappeler au moins le nom de Cervantès.

On a présenté cette opération comme une sorte de 13e croisade. Et feu Oussama bin Laden la qualifierait certainement ainsi. Honnêtement toutefois, cette numérotation ne veut pas dire grand-chose, à moins de s'en tenir à la définition faussement stricte qu'on donne classiquement : Urbain II au concile de Clermont en 1095 aurait donné le signal de la première, oublions la quatrième et l'abomination de 1204 (2), retenons que le pontificat romain de saint Pie V (1567-1572) préconisa celle-ci, effectivement aboutie à Lépante. Soulignons que la résistance chrétienne à l'expansion de l'islam et aux persécutions des califes et de émirs avait commencé beaucoup plus tôt. Et elle reprendra.

En l'occurrence cette victoire de l'occident appartient à la gloire de l'Espagne. Le règne de Philippe II est ordinairement présenté aujourd'hui sous le jour le plus négatif. Lorsque le réalisateur indien Shekhar Kapur consacra en 2007 un [excellent] film à la gloire d'Elizabeth Ire et à son "Âge d'or" on doit déplorer qu'il présente, à l'inverse, la Cour de Madrid et tous les catholiques comme un ramassis de benêts obscurantistes. Une telle impression mensongère s'impose efficacement au spectateur mal informét. Or, s'il importe, par ailleurs, de cerner la provenance des mythes mémoriels, et si la tâche des historiens consiste à leur tordre le cou, la question la plus urgente porte sur leurs conséquences actuelles. Les pays protestants de l'Europe du nord ont été confrontés aux mêmes périls, et ils le seront plus encore dans les temps à venir.

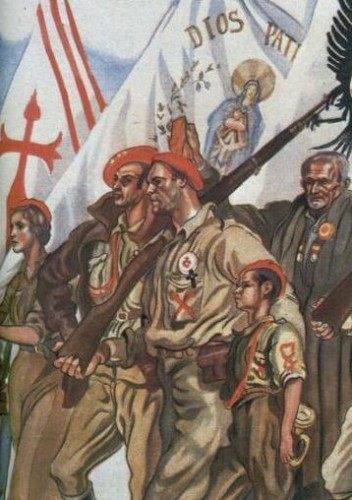

Au moment où le Pape appelait à la lutte contre la menace islamique qui pesait au XVIe siècle sur l'Empire vénitien, d'autres croyaient nécessaire d'attiser les guerres de religion qui dévastaient la France et qui, deux générations plus tard, ruineront l'Allemagne. Le "roi très chrétien", en l'occurrence les trois derniers Valois, quoique le royaume des Lys ait atteint les rives de la Méditerranée, s'abstint de participer à une ligue, où s'impliquèrent au contraire toutes les nationalités de l'Europe du sud. Celle-ci se constitua solennellement en mai, on ne l'a pas célébré. Elle assemblait Venise et Gênes, le duché de Savoie et le royaume de Naples, le roi d'Espagne, les États pontificaux, et les chevaliers de Malte. Cette coalition manqua de cohésion au-delà de la bataille. Elle renonça même après sa victoire à l'objet qui l'avait vu naître : la menace ottomane sur Chypre. La Sérénissime république de Vénitiens, dont la préoccupation commerciale dominait la politique, céda en 1573 l'île d'Aphrodite aux sultans de Constantinople. Le trône d'Osman était occupé par le fort médiocre Sélim II l'Ivrogne. Son empire ne fut sauvé que par un Slave de Bosnie le grand vizir Mehmed-pacha Sokolli. (3)

Tout ceci peut paraître bien lointain. J'avoue la faiblesse de considérer qu'il s'agit d'un scénario parfaitement cohérent et actuel. Chypre resta captive entre les mains de son conquérant pendant 300 ans, comme l'Espagne avait subi 800 ans le joug islamique. (4) Il vaut mieux ne jamais perdre les guerres, et même quand on l'emporte il faut savoir consolider sa victoire et gagner la paix.

Au-delà de tels truismes eux-mêmes oubliés, les souvenirs événementiels demeurent également indispensables. La résistance chrétienne que représente Lépante sera continuée, plus tard, par l'Autriche des Habsbourg en Europe centrale et dans les Balkans, puis par la Russie des tsars.

Aujourd'hui où l'on nous berce de "l'union pour la Méditerranée", autre nom du projet "Eurabia", on veut nous faire oublier au-delà même des batailles la vraie menace d'autodestruction, pire encore que de conquête, qui pèse sur tous les Européens. Baisser la garde face au choc des civilisations, forme un seul et même projet avec celui d'effacer nos racines et de renoncer à nos libertés.

JG Malliarakis

Apostilles

- Sur ce héros [oublié] de la chrétienté, vainqueur des Turcs, on lira avec plaisir le livre de Camille Paganel, "Histoire de Skanderbeg".

- On se reportera utilement à la petite "Histoire de l'empire Byzantin" de Charles Diehl.

- Issu du cruel mais efficace système appelé "devichirmé" – la cueillette – cet enfant arraché à sa famille, islamisé de force et formé pour servir de cadre à l'État, sera grand vizir de trois sultans successifs. Sur 26 grands vizirs dont on connaît l'origine, 11 semblent avoir été albanais, 6 grecs, 5 turcs, les autres tcherkesses, italiens, caucasiens ou serbes. C'est cela qui a permis à cet empire de durer.

- cf. "La Conquête de l'Espagne par les Arabes" par Jules de Marlès.

Si cet article vous a intéressé ...

vous aimerez certainement "La Question turque et l'Europe" par JG Malliarakis

Du même auteur, vient de paraître "L'Alliance Staline Hitler".

Puisque vous appréciez l'Insolent

Adressez-lui votre libre contribution financière !

00:10 Publié dans Actualité, Affaires européennes, Géopolitique, Histoire | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : lépante, histoire, actualité, europe, affaires européennes, turquie, empire ottoman, méditerranée, militaria, histoire navale, marine, batailles navales |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

dimanche, 22 mai 2011

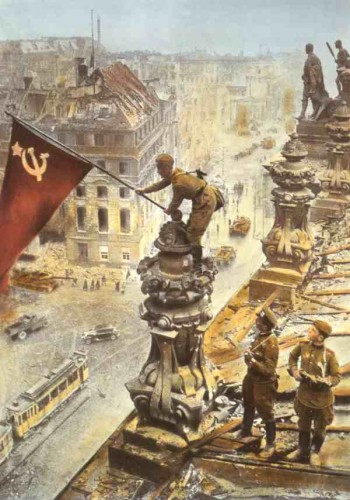

Präventivschlag Barbarossa

|

Stefan Scheil Präventivkrieg Barbarossa Fragen, Fakten, Antworten Band 26 der Reihe Kaplaken. 96 Seiten, kartoniert, fadengeheftet, 8.50 € ISBN: 978-3-935063-96-8 8,50 EUR incl. 7 % UST exkl. Versandkosten |

|

Der Historiker Stefan Scheil ist einer der besten Kenner der Diplomatiegeschichte zwischen 1918 und 1945. In mehreren Büchern hat er Entfesselung und Eskalation des II. Weltkriegs analysiert und der platten These widersprochen, Deutschland sei alleinverantwortlich für dessen Ausbruch und Ausweitung. Im vorliegenden kaplaken faßt Scheil seine Studien zum deutschen Angriff auf die Sowjetunion im Jahr 1941 zusammen. Er stellt und beantwortet die Frage, ob es sich um einen Überfall oder einen Präventivkrieg gehandelt habe. Scheil geht in seiner Argumentation von vier Bedingungen aus, die jeden Präventivkrieg grundsätzlich kennzeichnen, und legt sie als Maßstab an das „Unternehmen Barbarossa“ an.

Scheils Untersuchung mündet in über 50 Fragen, die jeder aufmerksame Leser selbst beantworten kann, bevor Scheil die Antwort gibt. Wer die Argumentation nachvollzieht, wer die Äußerungen und Planungen von sowjetischer Seite liest und den geheimen Aufmarsch der Roten Armee an der Westgrenze Rußlands zur Kenntnis nimmt, kann zuletzt Scheils Fazit nur zustimmen: „Wenn das Unternehmen Barbarossa nicht als Präventivkrieg eingestuft werden kann, hat der Begriff Präventivkrieg seinen Sinn überhaupt verloren.“

|

|

00:05 Publié dans Histoire, Livre, Militaria | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : histoire, seconde guerre mondiale, deuxième guerre mondiale, allemagne, livre, militaria |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

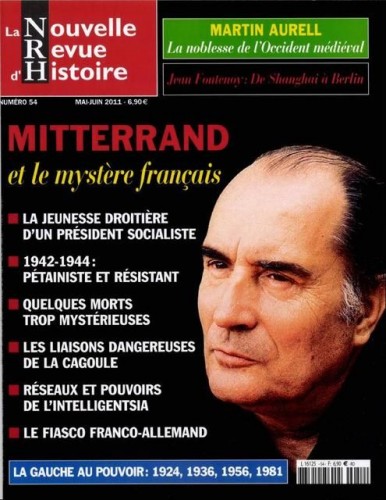

François Mitterrand & the French Mystery

François Mitterrand & the French Mystery

Dominique Venner

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com/

Translated by Greg Johnson

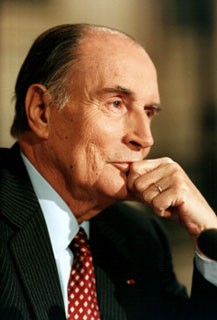

In the center of all the questions raised by the sinuous and contradictory path of François Mitterrand is the famous photograph of the interview granted to a young unknown, the future socialist president of the Republic, by Marshall Philippe Pétain in Vichy, on October 15th, 1942.

In the center of all the questions raised by the sinuous and contradictory path of François Mitterrand is the famous photograph of the interview granted to a young unknown, the future socialist president of the Republic, by Marshall Philippe Pétain in Vichy, on October 15th, 1942.

This document was known to some initiates, but it was verified by the interested party only in 1994, when he saw that his life was ending. Thirty years earlier, the day before the presidential election of 1965, the then Minister of the Interior, Roger Frey, had received a copy of it. He demanded an investigation which went back to a former local head of the prisoners’ association, to which François Mitterrand belonged. Present at the time of the famous interview, he had several negatives. In agreement with General de Gaulle, Roger Frey decided not to make them public.

Another member of the same movement of prisoners, Jean-Albert Roussel, also had a print. It is he who gave the copy to Pierre Péan for the cover of his book Une jeunesse française (A French youth), published by Fayard in September 1994 with the endorsement of the president.

Why did Mitterrand suddenly decide to make public his enthusiastic Pétainism in 1942–1943, which he had denied and dissimulated up to that point? It is not a trivial question.

Under the Fourth Republic, in December 1954, from the platform of the National Assembly, Raymond Dronne, former captain of the 2nd DB, now a Gaullist deputy, had challenged François Mitterrand, then Minister of the Interior: “I do not reproach you for having successively worn the fleur de lys and the francisque d’honneur [honors created by the Third Republic and Marhsall Pétain’s French State respectively – Trans.] . . .” “All that is false,” retorted Mitterrand. But Dronne replied without obtaining a response: “All that is true, and you know very well . . .”

The same subject was tackled again in the National Assembly, on February 1st, 1984, in the middle of a debate on freedom of the press. We were now under the Fifth Republic and François Mitterrand was the president. Three deputies of the opposition put a question. Since the past of Mr. Hersant (owner of Figaro) during the war had been discussed, why not speak about that of Mr. Mitterrand? The question was judged sacrilege. The socialist majority was indignant, and its president, Pierre Joxe, believed that the president of the Republic had been insulted. The three deputies were sanctioned, while Mr. Joxe declared loud and clear Mr. Mitterrand’s role in the Résistance.

This role is not contestable and is not disputed. But, according to the concrete legend imposed after 1945, a résistant past is incompatible with a Pétainist past. And then at the end of his life, Mr. Mitterrand suddenly decided to break with the official lie that he had endorsed. Why?

To be precise, before slowly becoming a résistant, Mr. Mitterrand had first been an enthusiastic Pétainist, like millions of French. First in his prison camp, then after his escape, in 1942, in Vichy where he was employed by the Légion des combattants, a large, inert society of war veterans. As Mitterrand found this Pétainisme too soft, he sought out some “pure and hard” (and very anti-German) Pétainists like Gabriel Jeantet, an old member of the Cagoule [the right-wing movement of the late 1930s dedicated to overthrowing the Third Republic – Trans.], chargé in the cabinet of the Marshal, one of his future patrons in the Ordre de la francisque.

On April 22nd, 1942, Mitterrand wrote to one his correspondents: “How will we manage to get France on her feet? For me, I believe only in this: the union of men linked by a common faith. It is the error of the Legion to have taken in masses whose only bond was chance: the fact of having fought does not create solidarity. Something along the lines of the SOL,[1] carefully selected and bound together by an oath based on the same core convictions. We need to organize a militia in France that would allow us to await the end of the German-Russian war without fear of its consequences . . .” This is a good summary of the muscular Pétainism of his time. Quite naturally, in the course of events — in particular after the American landing in North Africa of November 8th, 1942 — Mitterand’s Pétainism evolved into resistance.

The famous photograph published by Péan with the agreement of the president caused a political and media storm. On September 12th, 1994, the president, sapped by his cancer, had to explain himself on television under the somber gaze of Jean-Pierre Elkabbach. But against all expectation, the solitude of the accused, as well as his obvious physical distress, made the interrogation seem unjust, causing a feeling of sympathy: “Why are they picking on him?” It was an important factor that reconciled the French to their president. It was not an endorsement of a politician’s career. It was Mitterrand the man who had suddenly became interesting. He had acquired an unexpected depth, a tragic history that stirred an echo in the secret of the French mystery.

Note

1. The SOL (Service d’ordre légionnaire) was constituted in 1941 by Joseph Darnand, a former member of the Cagoule and hero of the two World Wars. This formation, by no means collaborationist, was made official on January 12th, 1942. In the new context of the civil war which is then spread, the SOL was transformed into the French Militia on January 31st, 1943. See the Nouvelle Revue d’Histoire, no. 47, p. 30, and my Histoire de la Collaboration (History of collaboration) (Pygmalion, 2002).

Source: http://www.dominiquevenner.fr/#/edito-nrh-54-mitterrand/3845286 [3]

Article printed from Counter-Currents Publishing: http://www.counter-currents.com

URL to article: http://www.counter-currents.com/2011/05/francois-mitterrand-and-the-french-mystery/

00:05 Publié dans Affaires européennes, Histoire, Nouvelle Droite, Politique | Lien permanent | Commentaires (0) | Tags : france, françois mitterrand, histoire, nouvelle droite, dominique venner, cinquième république |  |

|  del.icio.us |

del.icio.us |  |

|  Digg |

Digg | ![]() Facebook

Facebook

samedi, 21 mai 2011

Croatie 1945: une nation décapitée

Christophe Dolbeau:

Croatie 1945: une nation décapitée

Particulièrement impitoyable, la guerre à laquelle fut confronté l’État Indépendant Croate entre 1941 et 1945 s’est achevée, en mai 1945, par l’ignoble massacre de Bleiburg (1). Tueries massives de prisonniers civils et militaires, marches de la mort, camps de concentration (2), tortures, pillages, tout est alors mis en œuvre pour écraser la nation croate et la terroriser durablement. La victoire militaire étant acquise (3), les communistes entreprennent, en effet, d’annihiler le nationalisme croate : pour cela, il leur faut supprimer les gens qui pourraient prendre ou reprendre les armes contre eux, mais aussi éliminer les « éléments socialement dangereux », c’est à dire la bourgeoisie et son élite intellectuelle « réactionnaire ». Pour Tito et les siens, rétablir la Yougoslavie et y installer définitivement le marxisme-léninisme implique d’anéantir tous ceux qui pourraient un jour s’opposer à leurs plans (4). L’Épuration répond à cet impératif : au nom du commode alibi antifasciste, elle a clairement pour objectif de décapiter l’adversaire. Le plus souvent d’ailleurs, on ne punit pas des fautes ou des crimes réels mais on invente toutes sortes de pseudo délits pour se débarrasser de qui l’on veut. Ainsi accuse-t-on, une fois sur deux, les Croates de trahison alors que personne n’ayant jamais (démocratiquement) demandé au peuple croate s’il souhaitait appartenir à la Yougoslavie, rien n’obligeait ce dernier à lui être fidèle ! Parallèlement, on châtie sévèrement ceux qui ont loyalement défendu leur terre natale, la Croatie. De nouvelles lois permettent de s’affranchir des habituelles lenteurs judiciaires : lorsqu’on n’assassine pas carrément les gens au coin d’un bois, on les défère devant des cours martiales qui sont d’autant plus expéditives que les accusés y sont généralement privés de défense et contraints de plaider coupable…

Particulièrement impitoyable, la guerre à laquelle fut confronté l’État Indépendant Croate entre 1941 et 1945 s’est achevée, en mai 1945, par l’ignoble massacre de Bleiburg (1). Tueries massives de prisonniers civils et militaires, marches de la mort, camps de concentration (2), tortures, pillages, tout est alors mis en œuvre pour écraser la nation croate et la terroriser durablement. La victoire militaire étant acquise (3), les communistes entreprennent, en effet, d’annihiler le nationalisme croate : pour cela, il leur faut supprimer les gens qui pourraient prendre ou reprendre les armes contre eux, mais aussi éliminer les « éléments socialement dangereux », c’est à dire la bourgeoisie et son élite intellectuelle « réactionnaire ». Pour Tito et les siens, rétablir la Yougoslavie et y installer définitivement le marxisme-léninisme implique d’anéantir tous ceux qui pourraient un jour s’opposer à leurs plans (4). L’Épuration répond à cet impératif : au nom du commode alibi antifasciste, elle a clairement pour objectif de décapiter l’adversaire. Le plus souvent d’ailleurs, on ne punit pas des fautes ou des crimes réels mais on invente toutes sortes de pseudo délits pour se débarrasser de qui l’on veut. Ainsi accuse-t-on, une fois sur deux, les Croates de trahison alors que personne n’ayant jamais (démocratiquement) demandé au peuple croate s’il souhaitait appartenir à la Yougoslavie, rien n’obligeait ce dernier à lui être fidèle ! Parallèlement, on châtie sévèrement ceux qui ont loyalement défendu leur terre natale, la Croatie. De nouvelles lois permettent de s’affranchir des habituelles lenteurs judiciaires : lorsqu’on n’assassine pas carrément les gens au coin d’un bois, on les défère devant des cours martiales qui sont d’autant plus expéditives que les accusés y sont généralement privés de défense et contraints de plaider coupable…

Émanant d’un pouvoir révolutionnaire, aussi illégal qu’illégitime, cette gigantesque purge n’est pas seulement une parodie de justice mais c’est aussi une véritable monstruosité : en fait, on liquide des milliers d’innocents, uniquement parce qu’ils sont croates ou parce qu’on les tient pour idéologiquement irrécupérables et politiquement gênants. Au démocide (5) aveugle et massif qu’incarnent bien Bleiburg et les Marches de la Mort s’ajoute un crime encore plus pervers, celui que le professeur Nathaniel Weyl a baptisé aristocide et qui consiste à délibérément priver une nation de son potentiel intellectuel, spirituel, technique et culturel (« J’ai utilisé ce terme (aristocide) », écrit l’universitaire américain, « pour évoquer l’extermination de ce que Thomas Jefferson appelait ‘l’aristocratie naturelle des hommes’, celle qui repose sur ‘la vertu et le talent’ et qui constitue ‘le bien le plus précieux de la nature pour l’instruction, l’exercice des responsabilités et le gouvernement d’une société’. Jefferson estimait que la conservation de cette élite était d’une importance capitale »)-(6). Dans cette perspective, les nouvelles autorités ont quatre cibles prioritaires, à savoir les chefs militaires, les leaders politiques, le clergé et les intellectuels.

Delenda est Croatia

Au plan militaire et contrairement à toutes les traditions de l’Europe civilisée, les communistes yougoslaves procèdent à l’élimination physique de leurs prisonniers, surtout s’ils sont officiers. Pour la plupart des cadres des Forces Armées Croates, il n’est pas question de détention dans des camps réservés aux captifs de leur rang, comme cela se fait un peu partout dans le monde (et comme le faisait le IIIe Reich…). Pour eux, ce sont des cachots sordides, des violences et des injures, des procédures sommaires et au bout du compte, le gibet ou le poteau d’exécution. Il n’y a pas de circonstances atténuantes, aucun rachat n’est offert et aucune réinsertion n’est envisagée. Près de 36 généraux (7) sont ainsi « officiellement » liquidés et une vingtaine d’autres disparaissent dans des circonstances encore plus obscures. Colonels, commandants, capitaines, lieutenants et même aspirants – soit des gens d’un niveau culturel plutôt plus élevé que la moyenne – font l’objet d’un traitement spécialement dur et le plus souvent funeste. De cette façon, plusieurs générations de gens robustes et éduqués sont purement et simplement supprimées. Leur dynamisme, leur courage et leurs capacités feront cruellement défaut…

Vis-à-vis du personnel politique non-communiste, les méthodes d’élimination sont tout aussi radicales. Les anciens ministres ou secrétaires d’État de la Croatie indépendante, tout au moins ceux que les Anglo-Saxons veulent bien extrader (8), sont tous rapidement condamnés à mort et exécutés (9). Les « tribunaux » yougoslaves n’établissent pas d’échelle des responsabilités et n’appliquent qu’une seule peine. Disparaissent dans cette hécatombe de nombreux hommes cultivés et expérimentés, certains réputés brillants (comme les jeunes docteurs Julije Makanec, Mehmed Alajbegović et Vladimir Košak), et dont beaucoup, il faut bien le dire, n’ont pas grand-chose à se reprocher. Leur honneur est piétiné et la nation ne bénéficiera plus jamais de leur savoir-faire. (Remarquons, à titre de comparaison, qu’en France, la plupart des ministres du maréchal Pétain seront vite amnistiés ou dispensés de peine). La même vindicte frappe la haute fonction publique : 80% des maires, des préfets et des directeurs des grands services de l’État sont assassinés, ce qui prive ex abrupto le pays de compétences et de dévouements éprouvés. On les remplacera au pied levé par quelques partisans ignares et l’incurie s’installera pour longtemps. Moins brutalement traités (encore que plusieurs d’entre eux se retrouvent derrière les barreaux, à l’instar d’August Košutić ou d’Ivan Bernardic) mais tenus pour de dangereux rivaux, les dirigeants du Parti Paysan sont eux aussi irrémédiablement exclus de la scène politique ; leur formation politique, la plus importante du pays, est dissoute, tout comme les dizaines de coopératives et d’associations, sociales, culturelles, syndicales ou professionnelles, qui en dépendent… Coupé de ses repères traditionnels, le monde rural est désormais mûr pour la socialisation des terres et pour les calamiteuses « zadrougas » que lui impose l’omnipotente bureaucratie titiste.

Mort aux « superstitions »

Convaincus en bons marxistes que la religion est une superstition et que c’est bien « l’opium du peuple », les nouveaux dirigeants yougoslaves témoignent à l’égard des églises d’une hargne morbide. Les deux chefs de l’Église Orthodoxe Croate, le métropolite Germogen et l’éparque Spiridon Mifka sont exécutés ; âgé de 84 ans, le premier paie peut-être le fait d’avoir été, autrefois, le grand aumônier des armées russes blanches du Don… Du côté des évangélistes, l’évêque Filip Popp est lui aussi assassiné ; proche des Souabes, il était devenu encombrant… Vis-à-vis des musulmans, la purge n’est pas moins implacable : le mufti de Zagreb, Ismet Muftić, est publiquement pendu devant la mosquée (10) de la ville, tandis que dans les villages de Bosnie-Herzégovine, de nombreux imams et hafiz subissent un sort tout aussi tragique. Mais le grand ennemi des communistes demeure sans conteste l’Église Catholique contre laquelle ils s’acharnent tout particulièrement (11). Au cours de la guerre, le clergé catholique avait déjà fait l’objet d’une campagne haineuse, tant de la part des tchetniks orthodoxes que des partisans athées. Des dizaines de prêtres avaient été tués, souvent dans des conditions atroces comme les Pères Juraj Gospodnetić et Pavao Gvozdanić, tous deux empalés et rôtis sur un feu, ou les Pères Josip Brajnović et Jakov Barišić qui furent écorchés vifs (12). À la « Libération », cette entreprise d’extermination se poursuit : désignés comme « ennemis du peuple » et « agents de la réaction étrangère », des centaines de religieux sont emprisonnés et liquidés (13), les biens de l’Église sont confisqués et la presse confessionnelle interdite. « Dieu n’existe pas » (Nema Boga) récitent désormais les écoliers tandis que de son côté, l’académicien Marko Konstrenčić proclame fièrement que « Dieu est mort » (14). Au cœur de cette tempête anticléricale, la haute hiérarchie n’échappe pas aux persécutions : deux évêques (NN.SS. Josip Marija Carević et Janko Šimrak) meurent aux mains de leurs geôliers ; deux autres (NN.SS. Ivan Šarić et Josip Garić) doivent se réfugier à l’étranger ; l’archevêque de Zagreb (Mgr Stepinac) est condamné à 16 ans de travaux forcés et l’évêque de Mostar (Mgr Petar Čule) à 11 ans de détention. D’autres prélats (NN.SS. Frane Franić, Lajčo Budanović, Josip Srebrnić, Ćiril Banić, Josip Pavlišić, Dragutin Čelik et Josip Lach) sont victimes de violentes agressions (coups et blessures, lapidation) et confrontés à un harcèlement administratif constant (15). En ordonnant ou en couvrant de son autorité ces dénis de justice et ces crimes, le régime communiste entend visiblement abolir la religion et anéantir le patrimoine spirituel du peuple croate. Odieuse en soi, cette démarche totalitaire n’agresse pas seulement les consciences mais elle participe en outre de l’aristocide que nous évoquions plus haut car elle prive, parfois définitivement, le pays de très nombreux talents et de beaucoup d’intelligence. Au nombre des prêtres sacrifiés sur l’autel de l’athéisme militant, beaucoup sont, en effet, des gens dont la contribution à la culture nationale est précieuse, voire irremplaçable (16).

Terreur culturelle

Un quatrième groupe fait l’objet de toutes les « attentions » des épurateurs, celui des intellectuels. Pour avoir une idée de ce que les communistes purs et durs pensent alors de cette catégorie de citoyens, il suffit de se rappeler ce que Lénine lui-même en disait. À Maxime Gorki qui lui demandait, en 1919, de se montrer clément envers quelques savants, Vladimir Oulianov répondait brutalement que « ces petits intellectuels minables, laquais du capitalisme (…) se veulent le cerveau de la nation » mais « en réalité, ce n’est pas le cerveau, c’est de la merde » (17). Sur de tels présupposés, il est évident que les Croates qui n’ont pas fait le bon choix peuvent s’attendre au pire. Dès le 18 mai 1944, le poète Vladimir Nazor (un marxiste de très fraîche date)-(18) a d’ailleurs annoncé que ceux qui ont collaboré avec l’ennemi et fait de la propagande par la parole, le geste ou l’écrit, surtout en art en en littérature, seront désignés comme ennemis du peuple et punis de mort ou, pour quelques cas exceptionnels, de travaux forcés (19). La promesse a le mérite d’être claire et l’on comprend pourquoi le consul de France à Zagreb, M. André Gaillard, va bientôt qualifier la situation de « Terreur Rouge » (20)…

Les intentions purificatoires du Conseil Antifasciste de Libération ne tardent pas à se concrétiser et leurs effets sont dévastateurs. À Bleiburg comme aux quatre coins de la Croatie, la chasse aux intellectuels mal-pensants est ouverte. Dans la tourmente disparaissent les écrivains Mile Budak, Ivan Softa, Jerko Skračić, Mustafa Busuladžić, Vladimir Jurčić, Gabrijel Cvitan, Marijan Matijašević, Albert Haller et Zdenka Smrekar, ainsi que les poètes Branko Klarić, Vinko Kos, Stanko Vitković et Ismet Žunić. Échappant à la mort, d’autres écopent de lourdes peines de prison à l’instar de Zvonimir Remeta (perpétuité), Petar Grgec (7 ans), Edhem Mulabdić, Alija Nametak (15 ans) ou Enver Čolaković. Bénéficiant d’une relative mansuétude, quelques-uns s’en sortent mieux comme les poètes Tin Ujević et Abdurezak Bjelevac ou encore l’historien Rudolf Horvat qui se voient simplement interdire de publier. Tenus pour spécialement nocifs, les journalistes subissent quant à eux une hécatombe : Josip Belošević, Franjo Bubanić, Boris Berković, Josip Baljkas, Mijo Bzik, Stjepan Frauenheim, Mijo Hans, Antun Jedvaj, Vjekoslav Kirin, Milivoj Magdić, Ivan Maronić, Tias Mortigjija, Vilim Peroš, Đuro Teufel, Danijel Uvanović et Vladimir Židovec sont assassinés, leur collègue Stanislav Polonijo disparaît à Bleiburg, tandis que Mladen Bošnjak, Krešimir Devčić, Milivoj Kern-Mačković, Antun Šenda, Savić-Marković Štedimlija, le Père Čedomil Čekada et Theodor Uzorinac sont incarcérés, parfois pour très longtemps (21).