Bref manifeste pour un futur proche

par Gustave LEFRANÇAIS

« Il ne faut pas agir et parler comme nous l’avons appris par l’héritage de l’obéissance. »

Héraclite

« La vie pure est le mouvement de l’Être. »

Hegel, L’esprit du christianisme et son destin.

« À l’opposé du mot d’ordre conservateur: “ Un salaire équitable pour une journée de travail équitable ”, les prolétaires doivent inscrire sur leur drapeau le mot d’ordre révolutionnaire: “ Abolition du salariat”. »

Marx, Salaire, prix et profit.

Les positions synthétiques qui suivent conduisent toute action et toute réflexion qui n’entendent pas améliorer la société du spectacle de l’aliénation mais qui visent – a contrario – à redonner vraie vie à l’existence humaine. Elles témoignent des nécessaires jalons de l’énergie historique pour une véritable pratique révolutionnaire de destruction de la société de l’avoir et en défense intégrale de la communauté de l’être… Elles découlent de la rencontre plurielle et anti-dogmatique d’hommes et de femmes en quête de rencontre humaine à l’amont de tous horizons et à l’aval d’une seule perspective : celle d’une intervention cohérente pour atteindre la possibilité d’une situation où l’être de l’homme trouve effectivement l’homme de l’être.

Par conséquent, elles sont là la simple mais riche expression du mouvement réel de l’aspiration communiste qui – depuis des siècles de luttes déclarées ou obscures - traverse l’humanité après que celle-ci, en rupture de la tradition communautaire primordiale, eut été séparé de son rapport générique au devenir cosmique du vivre authentique et qu’elle cherche consciemment ou inconsciemment à retrouver le fil d’un temps non-monnayable où l’humain non-divisé ignorait les profanations de la domestication politique et de la tyrannie économique.

Avant la culture du travail pour la vente existait un monde où l’homme ne produisait que pour ses seuls besoins en des conditions où l’inestimable volupté d’habiter en les plaisirs de la terre sacrale n’avait pas de prix. À la suite du surgissement des productions de l’échange et du profit, a éclos la société de l’avoir qui a progressivement détruit la vieille et ancestrale communauté de l’être pour faire naître le dressage civilisationnel qui, d’ancien régime à domination mercantile faussement contrôlée à régime nouveau de despotisme marchand véritablement incontrôlable, a façonné progressivement les conditions d’émergence de l’actuelle dictature démocratique du marché totalitaire.

L’actuel énoncé ne dit rien d’autre qui ne soit le produit des expériences passées de l’humanité dés-humanisée en lutte perpétuelle de retour à la vérité d’elle-même, sur la base vivante et millénaire des incessantes jacqueries paysannes puis des insurrections ouvrières ainsi que des leçons qu’en ont tiré tout au long de l’histoire les organisations révolutionnaires qui ont su jaillir ici ou là pour déclarer que l’émancipation de l’humanité passait d’abord par la liquidation de la société de l’argent et de la mystification politique.

Les présents repères se réclament ainsi des apports subversifs et successifs de la Ligue des communistes de Marx et Engels, de l’Association internationale des travailleurs et de toutes les fractions radicales qui se sont manifestées dans la claire dénonciation du capitalisme d’État bolchévique en toutes ses variations successives de permanente duplicité complice avec les lois de la souveraineté marchande. La conscience historique qui est née de cette inacceptation voulue des obéissances à la seule jacasserie permise a su mettre en avant la nécessité de l’abolition du salariat et de l’État à l’encontre de toutes les impostures de perpétuation et de rénovation de la marchandise qui, de l’extrême droite à l’extrême gauche du Capital, n’aspirent qu’à maintenir ou moderniser le spectacle mondial de la société commerciale de la vie fausse.

Unité totalitaire du mode de production capitaliste en toutes ses variantes

Tous les pays de la planète du spectacle du fétichisme marchand, quelle que soit l’étiquette illusionniste dont ils se parent sont des territoires de l’oppression capitaliste soumis aux lois du marché mondial. Toutes les catégories essentielles du travail de la dépossession humaine y existent universellement, sous forme moderne ou retardataire, rudimentaire ou épanouie car l’argent en tant qu’équivalent général abstrait de toutes les marchandises produites par la marchandise humaine y triomphe partout en tant que dynamique de l’asservissement continûment et assidûment augmenté.

Dès lors, sous toutes les latitudes et sous toutes les longitudes règne la pure liberté de l’esclavage absolu qui en tant que puissance de la réification ravage tous les terrains de l’humain écrasé par l’abondance de la misère. Du centre de l’empire américain du spectacle de la marchandise à ses périphéries les plus oppositionnelles, le temps des choses enchaîne l’espace des hommes aux seules fins qu’en tout lieu la seule qualité qui leur soit reconnue soit celle que leur offre le mouvement général de la quantité circulante et de la libre comptabilité de l’économie des déchets narcissiques.

La Première Guerre mondiale a irrémédiablement marqué historiquement l’entrée en décadence du mode de production capitaliste qui connaît depuis lors des contradictions de plus en plus insolubles engendrant des conflits inter-impérialistes de plus en plus sanglants pour le re-partage régulier de la finitude des marchés saturés par l’infinité sans cesse réactivée de la baisse du taux de profit qui impose de toujours vendre en nombre croissant les produits de l’activité humaine capturée par le travail.

Le capitalisme enferme ainsi l’humanité dans un cycle permanent d’horreur généralisée – de crise, de guerre, de reconstruction puis à nouveau de crise… – qui en perpétuant l’inversion industrielle de la vie naturelle est la plus parfaite expression de sa décadence advenue. Celle-ci signale que dorénavant l’illimitation organique des exigences de ravage des rythmes du profit bute irrémédiablement sur les limites d’une solvabilité planétaire qui, même dopée de crédit en croissante fictivité pléthorique, ne peut parvenir à digérer la sur-production grandissante de travail cristallisée en matérialité illusoire et inécoulable. La seule alternative à cette situation où la valorisation du capital, malgré la mise en scène toujours de plus en plus féroce de ses machineries terroristes de destruction, ne parvient plus à possibiliser la falsification de la vie sociale, est la révolution pour la communauté humaine universelle devenue aujourd’hui visiblement indispensable pour tous ceux qui n’entendent pas tolérer de demeurer plus longtemps expropriés de leur propre jouissance humaine.

La tâche du prolétariat, c’est-à-dire la classe internationale de tous les hommes sans réserve, réduits à ne plus avoir aucun pouvoir sur l’usage de leur propre existence, est en chaque pays du spectacle de la réification mondialiste, la même : c’est celle de la destruction des rapports de production capitalistes.

Les luttes nationales de libération capitaliste

Ces luttes expriment l’idéologie du développement économique de classes dirigeantes locales qui n’aspirent à desserrer les liens avec le gouvernement du spectacle mondial que pour mieux exploiter elles-mêmes leur indigénat salarié. Elles ne peuvent évidemment se développer que dans le cadre des conflits inter-impérialistes qui aménagent le mensonge fondamental de la domination de classe pour le sauvetage du travail-marchandise.

La participation ou le soutien « critique » ou non du prolétariat à ces luttes, comme le veulent les publicitaires de la farce du soi-disant moindre mal pour permettre aux parents pauvres du capitalisme d’accéder à une meilleure position dans la division mondiale des tâches spectaculaires du vivre mutilé si elle peut intéresser les experts du marché des idées aliénées en quête de notoriété spectaculaire ne peut en revanche abuser les hommes de véridique passion radicale. Car ceux-ci savent pertinemment que tous ceux qui contestent les parents riches de la société moderne de l’exploitation interminable uniquement du point de la défense d’un réagencement plus équilibré des circonstances globales du Diktat du commerce généralisé, ne peuvent aboutir au mieux qu’à faire vendre la force de travail à un meilleur prix d’oppression.

Chair à transaction, chair à canon au profit d’un des camps en présence, l’humanité prolétarisée doit refuser de choisir entre la peste des grands États macro-impérialistes et le choléra des petits États micro-impériaux qui tous, contradictoirement, complémentairement mais solidairement ont toujours par delà leurs conflits de frères ennemis sur le terrain de la géo-politique du mensonge généralisé, constitué la Sainte-Alliance des fusilleurs du prolétariat.

Face à la réalité de la mondialisation despotique du quantitatif, la lutte de classe ne peut qu’être mondiale comme le proclamait dès 1848 Le Manifeste : « Les prolétaires n’ont pas de patrie ». Ceci au sens où si ces derniers ont bien en tant qu’hommes séparés d’eux-mêmes un reste de patrimoine cosmique d’enracinement non mercantilisable datant d’avant la théologie de la monnaie, la nation étatique née des Lumières de la raison marchande et qui a notamment provoqué les deux Holocaustes mondiaux du XXe siècle, n’est bien qu’une abstraction de marché destinée à satisfaire uniquement les exigences de richesse des calculs de l’échange.

L’appel « Prolétaires de tous les pays, unissez-vous ! » n’a jamais été aussi actuel. Après avoir détruit et digéré toutes les anciennes territorialités pré-capitalistes de jadis d’où il était sorti pour les fondre progressivement en l’unité de ses marchés nationaux, le spectacle de la mondialisation capitaliste est maintenant en train de liquider les nations pour les fusionner en une vaste grande surface hors-sol unifiée mondialement par le temps démocratique de la dictature de la valeur désormais totalement réalisée.

L’histoire ne repasse jamais les plats et tout essai de restauration finit inexorablement en comédie caricaturale. Il n’y aura pas de retour en arrière… Les peuples vont immanquablement disparaître et s’y substitueront alors des populations informes de libres consommateurs serviles de la temporalité échangiste du métissage obligatoire en l’adoration des galeries marchandes de la dépense. Ceux qui ne comprennent pas la réalité têtue de ce mouvement historique profond et irrévocable sont condamnés à l’appuyer par le fait même qu’ils le combattent à contre-temps à partir d’une simple dénonciation de ses effets. On ne peut lutter efficacement contre le spectacle mondial de l’économie politique en lui courant derrière pour regretter ce qu’il balaye et en tentant littérairement de faire réapparaître ce qui est justement en train de définitivement s’évanouir. On ne peut contre-dire et s’opposer véritablement au culte de la liberté de l’exploitation infinie qu’en livrant bataille en avant sur le seul terrain du triomphe dorénavant accompli de l’aliénation capitaliste totalement maîtresse de la totalité de la misère humaine.

Nous allons assister maintenant à la victoire réalisée du spectacle capitaliste qui va d’ailleurs se perdre elle-même en un processus d’échec cataclysmique où la dialectique de l’échange s’assimilant à tout usage possible, finira par conduire ainsi la marchandise à se consommer elle-même dans une baisse du taux de profit de plus en plus explosive.

Ainsi, même dans les pays dits « sous-développés » comme dans les « sur-développés », la lutte directe et radicale contre le Capital et tous les gangs politiques est la seule voie possible pour l’émancipation du prolétariat qui pour cela doit se nier en tant que tel en abolissant la marchandisation de la réalité.

Lorsque la réalisation toujours plus réalisée de la domination marchande sur la vie, rend toujours plus délicat et compliqué que les hommes distinguent et désignent leur propre néant en l’indistinction universelle de la marchandise qui a tout inversé, ces derniers se trouvent finalement positionnés en ce seul dilemme de refuser la totalité de la liberté de la tyrannie du marché ou rien. Ainsi, la théorie du vivre l’être est désormais ennemie déclarée de toutes les idéologies révolutionnaires de l’économie politique du mensonge qui en voulant soi-disant plus d’être en l’avoir maintenu, avouent tout bêtement qu’elles sont à la fois les ultimes secouristes de l’état de la possession et de la possession de l’État.

Les syndicats comme agents courtiers de la marchandise-travail

Simples appendices d’État, les syndicats même démonétisés restent les organes quotidiens de la contre-révolution capitaliste en milieu prolétarien. Leur fonction de vendeurs officiels de la force de travail à prix négociés en fait des régulateurs majeurs du marché du travail par rapport aux besoins du Capital et leur rôle de représentants de commerce du réformisme en même temps que leur fonction d’encadrement policier de la classe ouvrière les consacrent comme des piliers fondamentaux de la discipline et de la violence de l’ordre capitaliste dans les entreprises et dans la rue.

Destinés à maintenir le prolétariat comme marchandise, simple catégorie servile du Capital, les machineries bureaucratiques syndicales qui ne servent qu’à cadenasser la classe ouvrière et à saboter ses luttes pour les empêcher d’aller vers l’au-delà du reniement des hommes, ont participé à tous les massacres du mouvement révolutionnaire. La lutte du prolétariat pour cesser précisément de demeurer du prolétariat se fera sans eux et contre eux et elle réclame donc leur anéantissement.

La mascarade électorale

Les élections constituent un terrain de mystification destiné à perpétuer la dictature démocratique de la marchandise totalitaire librement circulante. Avec la séparation de plus en plus généralisée de l’homme et de son vivre, toute activité en s’accomplissant perd toute qualité humaine pour aller se mettre en scène dans l’accumulation de l’in-humain et le fétichisme du prix et de la facture. Chaque marchandise humaine, par la soumission mutilante aux cérémonies de l’ordre démocratique et électoral se fond ainsi dans la liberté du devenir-monde de la marchandise qui en réalisant le devenir-marchandise du monde organise la libre circulation des hommes en tant que disloqués d’eux-mêmes et coupés des autres mais justement rassemblés ensemble et en tant que tels dans la production pathologique et infini de l’isolement narcissique dans le paraître de l’acquisition.

Le prolétariat n’a rien à faire sur le terrain de la votation qui organise les territoires de la Cité du maintien de l’ordre capitaliste, pas plus à participer qu’à s’abstenir. Il n’a pas non plus à l’utiliser comme une « tribune de propagande » car cela ne fait que renforcer le mythe du despotisme démocratique de la valeur et contribue à dissimuler la réalité de la lutte de classe qui doit viser, elle, à détruire ostensiblement tous les rapports marchands qui soumettent l’homme aux réclames du spectacle des objets.

Tous les partis politiques, grands, moyens ou petits, dans l’opposition comme au pouvoir, au national comme à l’international, de la gauche la plus licencieuse à la droite la plus chaste, sont – en la synthèse de toutes leurs positions et oppositions – les chiens de garde solidaires du mouvement constant de monopolisation de l’histoire humaine par l’État de la marchandisation absolue et quand ils s’affrontent ce n’est qu’au sujet de la façon dont ils entendent dépouiller l’être humain de son humanitude.

À travers leurs multiples succédanés, les divers leurres réformistes de la politique du Capital n’ont servi qu’à museler le prolétariat en le liant à certaines fractions capitalistes artificiellement qualifiées en l’occurrence de moins nocives.

La lutte de classe radicale de l’être contre l’avoir se déroule en dehors de toute alliance politiste et combat tout ceux qui veulent soutenir, de façon « critique » ou non, la spécieuse idée que pourrait exister une démarche politique qui serait autre chose qu’une simple version du catalogue apologétique de l’humanisme de la marchandise. Le mouvement révolutionnaire vers l’autonomie ouvrière vise à réaliser la dictature anti-étatique du prolétariat, non point pour changer l’aliénation sous des formes aliénées mais pour abolir la condition prolétarienne elle-même et permettre à l’humain de se refonder communautairement sur la seule base de ses besoins génériques déliés de l’autocratie démocratique du solvable omni-présent.

La révolution pour la communauté de l’être

Elle ne vise pas à gérer d’une autre manière les réalités du marché et de l’échange puisqu’elle sait qu’il convient de les annihiler. Elle entend promouvoir le surgissement d’une communauté humaine véritable, affranchie des souffrances du compter, du spéculer et du bénéfice et apte à assumer les joies profondes de la vérité d’un plaisir et d’un besoin cosmiques anti-négociables. Elle est anti-politique car elle n’aspire pas à unifier le déchirement étatique de la vie et elle récuse tous les gouvernementalismes qui ne sont que les solutions de maintenance et de sauvetage du système de l’achat et de la vente de la vie confisquée par le travail du trafic. Elle a pour unique objectif : LA DESTRUCTION DU CAPITAL, DE LA MARCHANDISE ET DU SALARIAT SUR LE PLAN MONDIAL.

Pour cela, le mouvement social de l’humanité se dégageant de la marchandise en s’attaquant à l’ensemble des rapports capitalistes de l’aliénation et pour passer au mode de production communiste de la communauté de l’être, sera contraint de détruire de fond en comble l’État, expression politique de la domination de la dictature du spectacle marchand et ceci à l’échelle de la planète. En effet pour se nier en tant que dernière classe de l’histoire, le prolétariat ne peut que s’affirmer d’abord en tant que classe-pour-soi de l’éradication définitive de toutes les classes et de toutes les impuissances et tricheries de la division hiérarchiste de la nature humaine dénaturée.

La pratique de l’intervention communiste

Elle est en même temps un produit du mouvement social de la crise historique de l’argent et un facteur actif dans le développement théorique-pratique général de ce mouvement à mesure que la politique de l’économie se montre incapable d’assumer les contradictions de l’économie de la politique et que ceux qui tentent encore de d’administrer le spectacle de la fausse conscience sont rattrapés par la conscience vraie de ceux qui ne veulent plus justement y être dirigés.

Les groupes ou éléments du courant révolutionnaire vers la communauté de l’être ne sont pas en conséquence séparés de la classe en constitution subversive. Dès lors ils ne peuvent viser à la représenter, la diriger ou à s’y substituer.

Leur intervention en tant que moment du Tout le plus en dynamique de pointe radicale a pour axe principal la participation aux luttes du mouvement prolétarien contre le Capital tout en dénonçant systématiquement les mystifications de réformation de la marchandise et toutes les idéologies de ses défenseurs au sein de ce mouvement.

Elle ne peut se concevoir évidemment qu’à l’échelle de la planète dans la perspective de la PRATIQUE MONDIALE DU PROLÉTARIAT S’ABOLISSANT précisément en tant que PROLÉTARIAT, ceci contre tous les États et tous les interlocuteurs du marché de la politique et de l’autisme généralisé de la marchandise.

La communauté de l’être est cette critique charnelle, vivante, érotique et spirituelle qui renvoie à l’homme retrouvant la totalité de l’homme en un refus absolu des géographies de l’humain spolié et éparpillé par les divisions travaillistes du labeur et du loisir, du manuel et de l’intellectuel, de la campagne et de la ville telles que nées de l’émiettement et de la pulvérisation de l’existence qui est nécessairement appelée à devenir le territoire de tous les lieux de la centralisation morbide des arts de la marchandise.

La domination de la valeur est aujourd’hui en voie de total achèvement par le despotisme spectaculaire de la démocratie pure de la marchandise qui est en train de définitivement faire disparaître ou absorber toute son antériorité… La droite n’a plus rien à préserver de l’avant-Capital pendant que la gauche n’a plus rien à en supprimer… Le Capital a ainsi lui-même liquidé la politique en absorbant tout ce qui permettait encore à la gauche et à la droite de s’opposer complémentairement quant à la façon de gérer la servitude en la vie contrefaite… Il n’y a plus que la politique universelle de l’omnipotence de la marchandise dont droite et gauche ne forment plus que des écuries électorales de vacuité absolue et d’illusion industrielle… Le Capital n’a plus besoin de béquilles pour se mouvoir. Il est en train de se débarrasser de toutes les vieilles médiations idéologiques du passé… Il peut désormais organiser directement la non-vie de l’humanité par la seule action de la tyrannie de la valeur telle que le gauchisme sociétal de l’éternel présent de la marchandise désirante en a été le meilleur laboratoire de recherches infectieuses.

Nous assistons au commencement d’une nouvelle époque. Plus rien ne sera pareil à ces temps jadis où le monde n’était point encore devenu le total spectacle de la marchandise. Désormais, il n’est pas possible de s’attaquer sérieusement à un seul petit recoin de la misère humaine généralisée et des angoisses de l’homme perdu sans signaler du même coup que toute la vie sociale s’annonce comme une immense accumulation de souffles étouffés et coupés unifiés obscènement dans l’isolement concentrationnaire du marché des spectacle de l’image.

Dès lors celui qui ne se déclare pas comme choisissant la difficulté de la guerre au Tout de l’horreur méprisable du monde est condamné au prétexte de faire tout de suite quelque chose d’efficace, à seulement sombrer dans les facilités d’une simple et banale ré-écriture de l’empire de la passivité contemporaine.

La révolution pour la communauté humaine est toute entière contenue dans cette nécessité historique que l’humain ne peut jaillir qu’en tant que vécu des masses cessant pertinemment d’accepter de demeurer masses pour devenir hommes de la qualité brisant l’organisation quantitativiste du spectacle marchand de l’anti-vie humaine.

L’humanité prolétarisée, c’est à dire la classe universelle de tous les hommes exploités par la classe capitaliste du spectacle mondialiste de la marchandise, doit pour se nier en tant que tel, refuser d’admettre toute médiation entre elle et son auto-mouvement historique d’émancipation.

Cette auto-suppression du prolétariat comme émergence ontologique de l’être de l’homme réalisera dans le même mouvement la destruction des derniers épaves du racket politique, lesquels devront – face au prolétariat se niant – s’unifier objectivement en un seul mouvement: celui de la contre-révolution universelle du Capital…

Avec la mort de la marchandise, ce sera la fin de la dictature de la quantité anti-humaine, la fin de la démocratie et de son ultime contenu : le spectacle totalitaire de l’individu solipsiste qui permettra la résurgence enfin parachevée de la vraie communauté de l’être ; celle de l’espèce en son devenir naturel d’authentique cosmos humain.

Écoutons la vaste colère qui commence à monter et aidons là à aller au bout d’elle-même dans la sensualité du vrai goût de vie contre tous ceux qui entendent l’emprisonner dans la gestion optimisée du commerce enjolivé de l’obscurantisme scientifique des calculs éternels.

NI PARTI, NI SYNDICAT, VIVE LA GUERRE DE CLASSE MONDIALE POUR LA FIN DU SPECTACLE DE L’ÉCONOMIE POLITIQUE DE LA SERVITUDE EN L’OUBLI DE L’ÊTRE !

Paris, septembre 2010

Pour le collectif L’INTERNATIONALE, Gustave Lefrançais

Article printed from Europe Maxima: http://www.europemaxima.com

URL to article: http://www.europemaxima.com/?p=1719

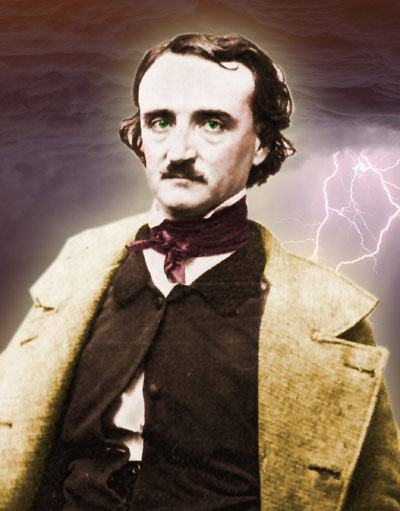

TODAY MARKS the 200th anniversary of the birth of the European-American literary genius and racially concious writer Edgar Allan Poe. I have paid my respects to the eternal memory of Edgar Poe in person at the Poe Museum in Richmond and at his and his beloved Virginia’s grave site in Baltimore, and I offer them again to all who read my words today.

TODAY MARKS the 200th anniversary of the birth of the European-American literary genius and racially concious writer Edgar Allan Poe. I have paid my respects to the eternal memory of Edgar Poe in person at the Poe Museum in Richmond and at his and his beloved Virginia’s grave site in Baltimore, and I offer them again to all who read my words today.

Deux volets paraissent se succéder dans ce petit livre, à première vue dissemblables, en tout cas appartenant à des sphères différentes : celui consacré à la culture, en l’occurrence celle que l’on destine, ou que l’on prête aux masses; et celui des médias, de la communication. Mais Christopher Lasch démontre que ces deux vecteurs de la société contemporaine, non seulement détiennent une importance capitale pour le projet qu’entretiennent les élites de contrôler efficacement le corps social, prévenant ainsi la guerre civile, comme l’indique pertinemment Régis Debray, dont le théoricien américain s’inspire parfois, mais aussi sont intimement imbriqués, tant la « culture » est devenue une affaire médiatique, fondée sur la publicité, la posture, l’esbroufe et le vide. Lasch montre même que le combat politique a pris le ton de cette culture de masse, faite d’annonces, de chocs, d’effets de miroirs, de clowneries (il cite Mark Rudd, Jerry Rubin et Abbie Hoffman, mais nous pourrions tout aussi bien invoquer les noms illustres de la carnavalesque « révolution » de 68, dont certains leaders ont bien fait leurs affaires), et que ce « style » fondé sur la fugacité de l’image et du son s’aligne intégralement sur la vérité marchande du capitalisme contemporain, fait de flux, de conditionnement, de légèreté idiote, et surtout de choix fallacieux, car puérils et grossiers.

Deux volets paraissent se succéder dans ce petit livre, à première vue dissemblables, en tout cas appartenant à des sphères différentes : celui consacré à la culture, en l’occurrence celle que l’on destine, ou que l’on prête aux masses; et celui des médias, de la communication. Mais Christopher Lasch démontre que ces deux vecteurs de la société contemporaine, non seulement détiennent une importance capitale pour le projet qu’entretiennent les élites de contrôler efficacement le corps social, prévenant ainsi la guerre civile, comme l’indique pertinemment Régis Debray, dont le théoricien américain s’inspire parfois, mais aussi sont intimement imbriqués, tant la « culture » est devenue une affaire médiatique, fondée sur la publicité, la posture, l’esbroufe et le vide. Lasch montre même que le combat politique a pris le ton de cette culture de masse, faite d’annonces, de chocs, d’effets de miroirs, de clowneries (il cite Mark Rudd, Jerry Rubin et Abbie Hoffman, mais nous pourrions tout aussi bien invoquer les noms illustres de la carnavalesque « révolution » de 68, dont certains leaders ont bien fait leurs affaires), et que ce « style » fondé sur la fugacité de l’image et du son s’aligne intégralement sur la vérité marchande du capitalisme contemporain, fait de flux, de conditionnement, de légèreté idiote, et surtout de choix fallacieux, car puérils et grossiers. Le point crucial de sa réflexion, et son originalité, tiennent à l’analyse de la modernité comme arrachement des racines, des modes d’existence qui étaient liées à une mémoire, un groupe, une classe, et qui se prévalaient d’habitudes, de pensées, d’arts qui devaient autant aux familles qu’aux métiers, dont beaucoup étaient artisanaux, qu’à toutes espèces d’appartenances, celle des amis, des terroirs, des activités de tous ordres, et, plus généralement, aux traits caractéristiques des ensembles dans lesquels la personne se coulait sans s’anéantir. C’est justement ce vivier, cette incalculable, incomparable expérience populaire, cette richesse multiséculaire, qui ont été arasés par la gestion bureaucratique et marchande des égos et des pulsions, par une éducation sans caractère, universaliste et mièvre, un traitement technique des besoins et souffrances humains. Les familles éclatent, les générations ne se transmettent plus rien, le nomadisme, vanté par l’hyper-classe, est méthodiquement imposé, les lavages de cerveau sont menés par la télé et des films idiots, la société de consommation abaisse et uniformise les goûts, instaure un totalitarisme d’autant plus efficace qu’il sollicite un hédonisme de bas étage. Ces danses, ces chants, cette poésie authentiques des anciennes sociétés rendaient plus libres, plus autonomes et fiers de soi que cette production « artistique » qui ressemble tant aux produits de la publicité, lesquels visent à rendre les cerveaux malléables et les cœurs mélancoliques. Le temps où une véritable création populaire irriguait celle des élites, à charge de revanche, comme on le voit par exemple dans les œuvres de Jean-Sébastien Bach, et précisément dans les grands chefs d’œuvres, semble révolu, détruit complètement par la barbarie marchande.

Le point crucial de sa réflexion, et son originalité, tiennent à l’analyse de la modernité comme arrachement des racines, des modes d’existence qui étaient liées à une mémoire, un groupe, une classe, et qui se prévalaient d’habitudes, de pensées, d’arts qui devaient autant aux familles qu’aux métiers, dont beaucoup étaient artisanaux, qu’à toutes espèces d’appartenances, celle des amis, des terroirs, des activités de tous ordres, et, plus généralement, aux traits caractéristiques des ensembles dans lesquels la personne se coulait sans s’anéantir. C’est justement ce vivier, cette incalculable, incomparable expérience populaire, cette richesse multiséculaire, qui ont été arasés par la gestion bureaucratique et marchande des égos et des pulsions, par une éducation sans caractère, universaliste et mièvre, un traitement technique des besoins et souffrances humains. Les familles éclatent, les générations ne se transmettent plus rien, le nomadisme, vanté par l’hyper-classe, est méthodiquement imposé, les lavages de cerveau sont menés par la télé et des films idiots, la société de consommation abaisse et uniformise les goûts, instaure un totalitarisme d’autant plus efficace qu’il sollicite un hédonisme de bas étage. Ces danses, ces chants, cette poésie authentiques des anciennes sociétés rendaient plus libres, plus autonomes et fiers de soi que cette production « artistique » qui ressemble tant aux produits de la publicité, lesquels visent à rendre les cerveaux malléables et les cœurs mélancoliques. Le temps où une véritable création populaire irriguait celle des élites, à charge de revanche, comme on le voit par exemple dans les œuvres de Jean-Sébastien Bach, et précisément dans les grands chefs d’œuvres, semble révolu, détruit complètement par la barbarie marchande.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

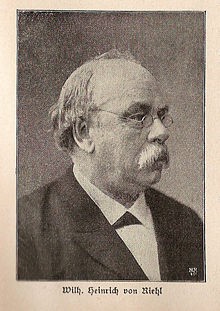

Il y a 170 ans, W. H. Riehl naissait, le 6 mai 1823, à Bieberich dans le pays de Hesse, aux environs de Giessen. Je m’étonne que son nom ne soit plus cité dans les publications conservatrices ou dextristes. Récemment, la très bonne revue allemande “Criticon” a consacré un article à Riehl. En 1976 était paru, dans une collection de livres publiés par l’éditeur Ullstein, le texte “Die bürgerliche Gesellschaft”, un des plus importants écrits socio-politiques de notre auteur, paru pour la première fois en 1851.

Il y a 170 ans, W. H. Riehl naissait, le 6 mai 1823, à Bieberich dans le pays de Hesse, aux environs de Giessen. Je m’étonne que son nom ne soit plus cité dans les publications conservatrices ou dextristes. Récemment, la très bonne revue allemande “Criticon” a consacré un article à Riehl. En 1976 était paru, dans une collection de livres publiés par l’éditeur Ullstein, le texte “Die bürgerliche Gesellschaft”, un des plus importants écrits socio-politiques de notre auteur, paru pour la première fois en 1851.

Elle nous fait bouger de plus en plus vite, ou surtout, elle nous fait croire que ce qui est bien c’est de bouger de plus et plus, et de plus en plus vite. En cherchant à aller de plus en plus vite, et à faire les choses de plus en rapidement, l’homme prend le risque de se perdre de vue lui-même. Goethe écrivait : « L’homme tel que nous le connaissons et dans la mesure où il utilise normalement le pouvoir de ses sens est l’instrument physique le plus précis qu’il y ait au monde. Le plus grand péril de la physique moderne est précisément d’avoir séparé l’homme de ses expériences en poursuivant la nature dans un domaine où celle-ci n’est plus perceptible que par nos instruments artificiels. »

Elle nous fait bouger de plus en plus vite, ou surtout, elle nous fait croire que ce qui est bien c’est de bouger de plus et plus, et de plus en plus vite. En cherchant à aller de plus en plus vite, et à faire les choses de plus en rapidement, l’homme prend le risque de se perdre de vue lui-même. Goethe écrivait : « L’homme tel que nous le connaissons et dans la mesure où il utilise normalement le pouvoir de ses sens est l’instrument physique le plus précis qu’il y ait au monde. Le plus grand péril de la physique moderne est précisément d’avoir séparé l’homme de ses expériences en poursuivant la nature dans un domaine où celle-ci n’est plus perceptible que par nos instruments artificiels. » Hartmut Rosa montre que la désynchronisation des évolutions socio-économiques et la dissolution de l’action politique font peser une grave menace sur la possibilité même du progrès social. Déjà Marx et Engels affirmaient ainsi que le capitalisme contient intrinsèquement une tendance à « dissiper tout ce qui est stable et stagne ». Dans Accélération, Hartmut Rosa prend toute la mesure de cette analyse pour construire une véritable « critique sociale du temps susceptible de penser ensemble les transformations du temps, les changements sociaux et le devenir de l’individu et de son rapport au monde ».

Hartmut Rosa montre que la désynchronisation des évolutions socio-économiques et la dissolution de l’action politique font peser une grave menace sur la possibilité même du progrès social. Déjà Marx et Engels affirmaient ainsi que le capitalisme contient intrinsèquement une tendance à « dissiper tout ce qui est stable et stagne ». Dans Accélération, Hartmut Rosa prend toute la mesure de cette analyse pour construire une véritable « critique sociale du temps susceptible de penser ensemble les transformations du temps, les changements sociaux et le devenir de l’individu et de son rapport au monde ».

Der 2009 verstorbene Philosoph Franco Volpi hatte bereits einige kleine Textsammlungen zu Arthur Schopenhauer herausgegeben, darunter Die Kunst, glücklich zu sein. Nun ist ein weiterer Band dieser Reihe erschienen. Die Kunst, sich Respekt zu verschaffen ist eine heitere Lektüre, die gegen einen Aberglauben über die Ehre ankämpft.

Der 2009 verstorbene Philosoph Franco Volpi hatte bereits einige kleine Textsammlungen zu Arthur Schopenhauer herausgegeben, darunter Die Kunst, glücklich zu sein. Nun ist ein weiterer Band dieser Reihe erschienen. Die Kunst, sich Respekt zu verschaffen ist eine heitere Lektüre, die gegen einen Aberglauben über die Ehre ankämpft.

Lust, when viewed without moral preconceptions and as an essential part of life’s dynamism, is a force.

Lust, when viewed without moral preconceptions and as an essential part of life’s dynamism, is a force.

Unlike Edmund Burke and Joseph de Maistre, Louis de Bonald devoted little space to analyzing the French Revolution itself. His focus instead was on understanding the traditional society which had been swept away. His review of Mme. de Staël’s

Unlike Edmund Burke and Joseph de Maistre, Louis de Bonald devoted little space to analyzing the French Revolution itself. His focus instead was on understanding the traditional society which had been swept away. His review of Mme. de Staël’s

Brett and Kate McKay

The Art of Manliness: Classic Skills and Manners for the Modern Man

Cincinnati: How Books, 2009

It’s hard not to like this book. However, it’s really the idea of the book that I like, rather than the book itself. In fact, I almost hesitate to write this review (which will not be wholly positive) because I think the authors have their hearts in the right place, and because I like their website http://artofmanliness.com/

When I showed this book to a young friend of mine he was incredulous: “Do we really need a manual on being a man?” he asked. Well, yes it appears we do. As the authors say in their introduction “something happened in the last fifty years to cause . . . positive manly virtues and skills to disappear from the current generations of men.” They don’t really tell us what they think that something is, but two paragraphs later they remark: “Many people have argued that we need to reinvent what manliness means in the twenty-first century. Usually this means stripping manliness of its masculinity and replacing it with more sensitive feminine qualities. We argue that masculinity doesn’t need to be reinvented.”

I wanted to let out a cheer at this point, but I was sitting in the American Film Academy Café in Greenwich Village, surrounded by young white male geldings and their Asian girlfriends. So I kept my mouth shut and noted to myself that the McKays are clearly not PC, though there are minor nods to political correctness here are there. One gets the feeling that they know more than they are letting on in this book. And one gets the feeling they are employing a simple and sound strategy: to seduce male readers with the natural appeal of traditional manliness – while revealing just-so-much of their political incorrectness so as not to completely alienate their over-socialized readers.

Still, the McKays are pretty socialized themselves, and one sees this immediately on opening the book and finding that it is dedicated to two members of “the greatest generation.” Ugh. Yes, I do think there’s much to admire about my grandfather’s generation, but I long ago came to detest the conventional-minded romanticism about America’s great crusade in WWII. And the very use of the phrase “greatest generation” has become a cliché.

However, the real trouble begins after the introduction, when one finds that the first section of the book is devoted to how to get fitted for a suit. Then we are instructed in how to tie a tie. For some unaccountable reason the tying of the Windsor knot is included here. (Like Ian Fleming, I have always regarded the Windsor knot as a mark of a vain and unserious man.) This is followed by sections on how to select a hat, how to iron a shirt, how to shave, and how not to be a slob at the dinner table. So far so good: I know all this stuff, so I guess I’m pretty manly. Of course, the problem here is that this is all in the realm of appearance. To be fair, the McKays do go on to include much in their book about character, but one must wade through a lot of inessential stuff to get there.

At one point we are instructed in how to deliver a baby. The McKays’ core piece of advice here is “get professional help!” Curiously, this is also the central tenet of their brief lectures on dealing with a snakebite and landing a plane. The baby having been delivered, the reader will find further instructions on how to change a diaper and how to braid your daughter’s hair. (This is what happens when you co-author a book with your wife.) The McKays’ advice on raising children is sound. They advise us not to try and be our child’s best friend.

Once you have tended to your daughter’s snakebite and braided her hair (in that order, please), you can turn to manlier things like how to win a fight, how to break down a door, how to change a flat tire, how to jump start a car, how to go camping, how to navigate by the stars, and how to tie knots. Then it will be Miller time, and you will want some manly friends to hang out with.

The section on male friendship, in fact, is one of the best parts of the book. The McKays remind us that in ancient times “men viewed male friendship as the most fulfilling relationship a person [i.e., a man] could have.” They attribute this, however, to the fact that men saw women as inferior. This is at best a half-truth. The real reason men saw male friendship as more fulfilling than relations with women is because it is. There are vast differences between men and women, and while they may be able to have close, loving relationships they never really understand each other, and their values clash.

Women are primarily concerned with the perpetuation of the species. They are the peacemakers, who just want us all to get along, because their main concern is what Bill Clinton called “the children.” By contrast, men find their greatest fulfillment in achieving something outside the home: they are only fully alive when they are fighting for some kind of value. A man can only be truly understood by another man.

Thus was born what the McKays refer to as “the heroic friendship”: “The heroic friendship was a friendship between two men that was intense on an emotional and intellectual level. Heroic friends felt bound to protect one another from danger.” The McKays devote some discussion to the decline of close male friendships, and they have a lot to say about the disappearance of affection among male friends.

A while back I found myself in a bookstore flipping through a book of photographs from WWII. Many of them depicted soldiers, sailors, and marines relaxing or goofing around. What was remarkable about many of these pictures was the affection the men displayed for one another. There was one photo, for example, of a sailor asleep with his head in another sailor’s lap. This is the sort of thing that would be impossible today, because of fear of being thought “gay.” The McKays mention this problem. As George Will once said, the love that dare not speak its name just can’t seem to shut up lately. And it has ruined male bonding. Thus was born the “man hug” with the three slaps on the back that say I’M (THUMP) NOT (THUMP) GAY (THUMP). (Yes, the McKays instruct us on how to perform the man hug in both its American and international versions.)

Another thing that has ruined male friendships is women, but in a number of different ways. First of all, as every man knows, women have now invaded countless previously all-male areas in life. This usually results in ruining them for men. Second, many women resent it when their husbands or partners want to spend time with their male friends. In earlier times, men would spend a significant amount of time away from their wives working or playing with male peers. But no longer. Now women expect to be their husband’s “best friend,” and men today passively go along with this. The result is that they often become completely isolated from their male friends. It is quite common today, in fact, for men to expect that marriage means the end of their friendship with another man. Please note that all of the above problems have only been made possible by the cooperation of men – by their not being manly enough to say “no” to women.

Eventually, one finds the McKays dealing with matters having to do with manly character, such as their discussion of the characteristics of good leadership. A lot of what they have to say is sound advice, but it is not without its problems. At one point they invoke old Ben Franklin and his homey list of virtues. Anyone interested in this topic should read D. H. Lawrence’s hilarious demolition of Franklin in Studies in Classic American Literature. Franklin is the archetypal American, extolling (among other things) temperance, frugality, industry, and cleanliness. This is setting our sights very low, and it’s not the least bit manly. If I’m going to take lessons in manliness from an American I’d much rather get them from Charles Manson.

There are other problems I could go on about, such as the McKays advising us to give up porn because it “objectifies women” (“But that’s the whole point!” a friend of mine responded when I told him this). However, as I said earlier, their heart is in the right place. Whatever its flaws, this book is a celebration of traditional manhood and an honest, well-intentioned attempt to improve men.

Still, there is something undeniably creepy and postmodern about this book. If you follow all of its instructions you won’t be a traditional manly man, you’ll be an incredible, life-like simulation of one. The reason is that everything they talk about came naturally to our forebears. It flowed from their characters, and their characters flowed from their life experience. But their life experience was quite different from ours. They were not constantly shielded from danger and from risk taking. They had myriad ways open to them to express and refine their manly spirit. They had manly rites of passage. Their spirits were not crushed by decades of PC propagandizing. They had been tested by wars, famines, depressions. They were tough sons of bitches, and nobody needed to tell them how to win a fight. And if you tried to tell them how to braid their daughters’ hair you’d better be ready for a fight.

True manliness is not the result of acquiring the sort of “how to” knowledge the McKays try to provide us with. Manliness is not an art, not a techne – but it’s inevitable that we moderns, even good moderns like the McKays, would think that it is. Manliness is a way of being forged through trials and tribulations. In a world without trials and tribulations, in the “safe” and “nice” modern, industrial, liberal, democratic world it’s not at all clear that true manliness is possible anymore. Except, perhaps, through rejecting that world. The subtext to The Art of Manliness is anti-modern. But the achievement (or resurrection) of manliness has to raise that anti-modernism out from between the lines and make it the central point.

At its root, modernity is the suppression of manly virtues and manly values. This is the key to understanding the nature of the modern world and our dissatisfaction with it. Manliness today can only be truly asserted through revolt against all the forces arrayed against manliness – through revolt against the modern world .

.