From Romanticism to Traditionalism

Thomas F. Bertonneau

Ex: http://peopleofshambhala.com

The movement called Romanticism belongs chronologically to the last two decades of the Eighteenth and the first five decades of the Nineteenth Centuries although it has antecedents going back to the late-medieval period and sequels that bring it, or its influence, right down to the present day. Historically, and in simple, Romanticism is the view-of-things that succeeds and corrects its precursor among the serial views-of-things that have shaped the general outlook of the Western European mentality – what historians of ideas call Classicism, and which they identify as the worldview of the Enlightenment. A good definition of Classicism is: The devotion to prescriptive orderliness for its own sake in all departments of life; the submission of all things to measure, decorum, and, using the word metaphorically, the geometric ideal. Classicism implies the conviction that reason, narrowly delimited, is the highest faculty, and indeed almost the sole faculty worth developing. The Classicist believes that life can be perfected by rationalization. Certainly this is how the Romantics saw Classicism, but it is also in broad terms how the Classicists saw themselves. According to its own dichotomy, Romanticism would be a view of existence consisting of tenets diametrically opposed to those of Classicism.

Detail of “The Course of Empire: Desolation,” 1836, oil on canvas, by Thomas Cole (1801-1848), founder of the Hudson River School.

And so largely it was or is, as Romanticism is by no means a dead issue. As the Romantic sees it, imposed or conventional order tends to distort or obliterate the natural order; and by “natural order” the Romantics would have understood not only the order of nature, considered as Creation, but the order present in social adaptation to the natural order, as when agriculturalists follow the cycle of the seasons and attune their lives with the life of the soil or when builders of monuments and temples go to great effort to align them astronomically. In addition, the Romantic believes that a bit of disorder might stimulate and enliven life, preventing it from becoming stiff and ossified; that the quirky and unexpected can exert a benevolent influence. The Romantic also values emotion and intuition as much as he values reason, which he by no means disdains although he defines it more broadly than the Classicist. The Romantics explicitly rejected the utilitarian arguments of the Classicists. Romanticism prefigures and is the likely source of what in the second half of the Twentieth Century came to be known as Traditionalism.

I. Characteristics of Romanticism. Where the geometrically patterned gardens of the French kings, like those designed by Claude Millet in 1632 for Louis XIV at Versailles, might stand for the Classical Spirit, the “English Garden,” with its meandering paths, sprawling bushes, and indifference to the weeds might stand for the Romantic Spirit. Where Classicism took as its model Greece or Rome, Romanticism looked to the Middle-Ages. Where Classicism venerated the purest, most elevated Attic style of speech, Romanticism cultivated the Gothic, the Celtic, and the regional dialect; it was not averse to rude or rustic idiom. Classical playwrights like Pierre Corneille (1606 – 1684) and Jean Racine (1639 – 1699) imitated Euripides and Seneca; Romantic playwrights like Friedrich Schiller (1788 – 1805) and Victor Hugo (1802 – 1885) imitated Shakespeare, whom Voltaire had dismissed as a barbarian and his work as a formless affront to the unities. Classicism concerns itself with form, which prescribes content, Romanticism with content, which then suggests the form.

What have the scholars written about Romanticism? None exceeds the scholarly stature of Jacques Barzun (1907 – 2012), whose study From Dawn to Decadence: 500 Years of Western Cultural Life (2000) devotes three chapters to Romanticism. Remarking that Romanticism had, in the broadest sense, something of the quality of a religious or spiritual awakening, and that, unlike Classicism, it extended its horizon of curiosity very far indeed – as for example into myth and folklore considered as other than mere superstition – Barzun writes:

With their searching imagination in literature and art, it could be expected that the Romanticists’ intellectual tastes would be anything but exclusive. They found the Middle Ages a civilization worthy of respect; they relished folk art, music, and literature; they studied Oriental philosophy; they welcomed the diversity of national customs and character, even those outside the [Eighteenth Century] cosmopolitan circuit; they surveyed dialects and languages with enthusiasm. This was a genuine multiculturalism, the wholehearted acceptance of the remote, the exotic, the folkish, [and] the forgotten.

Barzun adds that, “in Romanticism, thought and feeling are fused; [Romanticism’s] bent is toward exploration and discovery at whatever risk of error or failure; the religious emotion is innate and demands expression… the divine may be reached through nature or art.” Under Barzun’s description, Romanticism would be humanly more whole than Classicism, with the latter excluding rather than incorporating the emotional impulse while granting to intuition a key role in the exploration of existence.

The Norwegian scholar, F. J. Billeskov Jansen (1907 – 2002), writing in the compendium Romantikken: 1800 – 1830 (Verdens Litteratur Historie, V. III, 1972), asserts that:

Opplysningstidens mennesker hade fryktet lidenskapene, som kunne true den sunne fornuft. Alt hos Klopstock ble likevel den religiøse lidenskap frigjort, og hos Rousseau elskovspasjonen og natursvermeriet. I romantikkens tidsalder blir diktere drømmere, Sjelen utvides I lengsel mot uendligheten, gjennom innføling forener poeten med nature, hans fantasi fører ham langt bort på eventyrets vinger eller langt tilbake i historien; hans håp får form av religiøse visjoner.

[The men of the Enlightenment had feared the passions, which could threaten right reason. Simultaneously in [the work of Friedrich Gottlieb] Klopstock religious enthusiasm gained liberation, (just) as in the work of (Jean-Jacques) Rousseau did amorous passion and ecstasy in nature. In the age of romanticism, poets became dreamers. The soul expands in longing for infinity, the poet attaining oneness with nature through his inward feeling, while his imagination leads him far afield on the wings of adventure or far back into history; his hope takes the form religious visions.]

Elsewhere in the same volume, another scholar characterizes Romanticism as a return of Platonic theology. Certainly Plato’s myths of the “Ladder of Philosophy,” “The Winged Horses and their Charioteer,” and “The Cave” find their later reflection in the imagery of the Romantic poets. For Plato, importantly, the phenomena of this world point to a purely spiritual world – the realm of God and the Ideas. We find a similar attitude in the poetry William Blake (1757 – 1827) and in that of William Wordsworth (1770 – 1850). The main point to be stressed, however, is Jansen’s description of Romanticism as the labor of the soul to break free from the trammels of degraded matter and to rejoin a vital spirit that suffuses the universe and renders it intelligible. The Romantics concluded that the assumptions of rationalism were parochial and constricting; that they did not give a true account of humanity or the universe.

In his study of Poetic Diction (1928), philologist and literary critic Owen Barfield (1898 – 1997) attempts to identify and prescind the fundamental Romantic ideas, one of which has to do with the role of “the rational principle”:

Now although, without the rational principle, neither truth nor knowledge could have been, but only life itself, yet that principle cannot add one iota to knowledge. It can clear up obscurities, it can measure and enumerate with greater and ever greater precision, [and] it can preserve us in the dignity and responsibility of our individual existences. But in no sense can it be said… to expand consciousness. Only the poetic can do this: only poesy, pouring into language its creative intuitions, can preserve its living meaning and prevent it from crystallizing into a kind of algebra. “If it were not for the Poetic or Prophetic character,” wrote William Blake, “the philosophic and experimental would soon be at the ratio of things, and stand still, unable to do other than repeat the same dull round.”

For Barfield, Romanticism qualifies not only as a revolt against the strictures of the Enlightenment; it is not only the accession of a new type of taste or sensibility that supersedes an earlier one: It is a change – and, for Barfield, a positive development – in human consciousness. Understood in the way that Barfield, Jansen, and Barzun see it, Romanticism resembles – or, rather it anticipates –Traditionalism. In The Crisis of the Modern World (1927), for example, René Guénon (1886 – 1951) describes the modern person as averse to referring “beyond the terrestrial horizon” and as crediting “no knowledge beyond what proceeds from the sense.” For Guénon, the modern world “is anti-Christian because it is essentially anti-religious; and it is anti-religious because, in a still wider sense, it is anti-traditional.” Writing in Harry Oldmeadow’s anthology The Betrayal of Tradition (2005) and invoking the spirit of T. S. Eliot, Brian Keeble asserts that fullness of humanity requires contact with “the transcendent dimension”; and, calling on Blake, he invokes the “sacred reality of the spirit.”

II. The Romantic Subject. Romanticism saw a great flowering of lyric poetry, and this was no coincidence. Lyric poetry is personal, even egocentric, poetry; or it is poetry personal in character even in the case where the putative “I” who speaks in the poem is purely fictional and is not to be identified with the author. The name lyric suggests the solo singer accompanying himself on the lyre, bursting out in song, as the spirit takes him. Lyric poetry is expressive: It represents in externalized imagery the internal state, intellectual or emotional, of the poet. Of course, inner states usually correlate themselves with external circumstances and conditions. Anyone who comments on the soul also necessarily comments on the world. The Romantics seized on the lyric as their primary mode of poetizing because the conventions of lyric so perfectly suited that part of the Romantic program that concerned the exploration of the subject’s inner life. Of course, the Romantic poet interests himself in much more than in pouring out the contents of his overflowing heart. That would be a sophomoric misapprehension. On the contrary, for the talented poet, well-schooled, mentally acute, moved by inveterate curiosity about the world, even a brief lyric poem can be the vehicle of a subtle critique or argument. If the Romantic poet were a prophet then he would also be a philosopher.

What does it mean to be a subject, an ego, an “I”? Subjectivity is self-consciousness, an abiding awareness that one is this person, with this biography (always thus far), and with these relations to and with and in the world – and not some other person with other relations. But every subject, every self-conscious person, is aware that the world is full of other self-conscious persons whose subjectivity, as he infers, is generically like his own right down to the detail that each has (or ought to have) a similar sense of his own particularity and difference from the others. Beyond persons, places, and things, the subject senses – although he can never empirically grasp – a totality of things, a cosmos, and an authorial or organizing principle, for which the common name is God. Wisdom consists in knowing that there was a world indefinitely before his own subjectivity began and there will be a world indefinitely after his own subjectivity ceases; he is a part of something larger than himself, which lies beyond the limits of his will.

Mood conditions subjectivity. The typical self-consciousness addressed in the previous paragraph should be qualified as the healthy self-consciousness. Because, however, no one can keep the world absolutely at bay, he must suffer the impingements of the world, whether happily or sadly. Forces beyond a subject’s control can alienate him from himself and through ignorance or perversity he can exacerbate his alienation. The Romantics believed that the worldview of Classicism, or the Enlightenment, described life and the world falsely, and that those who embraced its falsehoods must in some way become alienated. The Romantics regarded with acute skepticism the modern claims concerning material progress. “The world is too much with us, late and soon, / Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers,” wrote Wordsworth. In the labyrinth of the new metropolis, the soul might once again lose its way and suffer, as men once did in the Cities of the Plain, and experience pure indifference with respect to its own sickness. What kind of civic environment would arise from the presence together in large urban agglomerations of millions of such afflicted people? The psychic problem must inevitably become a social and a cultural problem.

It is worth quoting Wordsworth’s sonnet in full:

The world is too much with us; late and soon,

Getting and spending, we lay waste our powers;—

Little we see in Nature that is ours;

We have given our hearts away, a sordid boon!

This Sea that bares her bosom to the moon;

The winds that will be howling at all hours,

And are up-gathered now like sleeping flowers;

For this, for everything, we are out of tune;

It moves us not. Great God! I’d rather be

A Pagan suckled in a creed outworn;

So might I, standing on this pleasant lea,

Have glimpses that would make me less forlorn;

Have sight of Proteus rising from the sea;

Or hear old Triton blow his wreathèd horn.

The Romantics understood that consciousness rises to acuity in events and crises, like that experienced by Wordsworth’s monologist in the stale abjection of his despair. The growth of consciousness proceeds punctually rather than gradually, and it entails the tribulations of a solemn pilgrimage. Lyric poetry, being the poetry of the subject’s self-consciousness, therefore also tends to be the poetry of sudden events – discrete moments in which the subject suddenly discovers something about himself, the world, or himself in relation to the world, that hitherto he did not know and knowledge of which alters him. It might be, as in the case of “The world is too much with us,” the discovery of one’s own spiritual poverty; it might be an access of grace. Such moments sometimes bear the name of epiphany; they are in any case always revelatory – and they cannot be solicited. They impose themselves, as if by external guidance, as gifts, upon the percipient.

The epiphanic or revelatory quality of lyric poetry has to do with its effort to appear spontaneous. Every work of art requires arduous labor, even a fourteen-line sonnet, but Wordsworth, for example, insisted that he drew inspiration from abrupt visionary experiences and that articulating the vision although onerous entailed given textual form to a unitary idea. Discussing the origin of his major poems – The Prelude, The Excursion, and the unfinished Recluse – in letters to his friends, Wordsworth situated himself as the channel for impulses that had befallen him, as revelation befalls the prophet, whether he seeks his election or not.

The Romantic subject resembles – or, rather, it anticipates – the Traditionalist subject, as Guénon, Nicolas Berdyaev (1874 – 1948), and others have defined it. Guénon himself in The Reign of Quantity and the Signs of the Times (1945) characterizes modern man as having “lost the use of the faculties which in normal times allowed him to pass beyond the bounds of the sensible world.” This loss leaves modern man alienated from “the cosmic manifestation of which he a part”; in Guénon’s analysis modern man assumes “the passive role of a mere spectator” and consumer, which is exactly how Wordsworth saw it. Of course, Guénon does not write of loss as an accident, but as the logical consequence of choices and schemes traceable to the Enlightenment. As Wordsworth put it, “We have given our hearts away – a sordid boon.”

According to Berdyaev, writing in The Destiny of Man (1931), “Man is not a fragmentary part of the world but contains the whole riddle of the universe and the solution of it.” Berdyaev asserts that, contrary to modernity, “man is neither the epistemological subject [of Kant], nor the ‘soul’ of psychology, nor a spirit, nor an ideal value of ethics, logics, or aesthetics”; but, abolishing and overstepping all those reductions, “all spheres of being intersect in man.” Berdyaev argues that, “Man is a being created by God, fallen away from God and receiving grace from God.” The prevailing modern view, that of naturalism, “regards man as a product of evolution in the animal world,” but “man’s dynamism springs from freedom and not from necessity”; it follows therefore that “evolution” cannot explain the mystery and centrality of man’s freedom. When Berdyaev brings “grace” into his discussion, he echoes the original Romantics, whose version of grace was the epiphanic vision, the event answering to a crisis that brings about the conversion of the fallen subject and sets him on the road to true personhood.

III. Romantic Nature. The Romantic redefinition of nature, which the Romantics invariably capitalize as Nature, runs in parallel with the Romantic redefinition of selfhood. Where the Enlightenment had reduced nature to material processes – geological, chemical, physiological, mechanical, and optical – with no reference to anything outside themselves, Romanticism in reaction posited Nature not only as vital throughout but also as meaningful, and natural phenomena as pointing beyond themselves to things supernatural. This redefinition of nature was perhaps less a total innovation than it was the re-appropriation of an old idea going back to late-medieval thinkers like Jakob Boehme (1575 – 1624), Paracelsus (1493 – 1541), and even Johannes Kepler (1571 – 1630), who saw in nature a decipherable living message that implies a message-maker whose motivation must be that he wishes to establish contact with human beings. Behind those figures lies Christian Platonism. Under this late-medieval idea, the sensitive soul can not only come into communication through nature with what lies beyond nature; but he can also, through nature, come into communion with what is beyond nature. In Christian, rather than pagan, terms, the Romantic rediscovers Nature as “The Book of Nature,” a kind of supplement to the two Testaments, whose author is God, as normally or eccentrically conceived by the individual writer-thinker.

A longstanding and not altogether inaccurate thumbnail categorization of Romantic poetry is that it is nature poetry. The Romantic penchant for verbal picturesque redoubles the plausibility of the claim. Here, for example, is Samuel Taylor Coleridge (1772 – 1834) conjuring forth the abyss that lies beneath “The Pleasure Dome of Kubla Khan” in the fragmentary poem (1798) of that name.

But oh! that deep romantic chasm which slanted

Down the green hill athwart a cedarn cover!

A savage place! as holy and enchanted

As e’er beneath a waning moon was haunted

By woman wailing for her demon-lover!

And from this chasm, with ceaseless turmoil seething,

As if this earth in fast thick pants were breathing,

A mighty fountain momently was forced:

Amid whose swift half-intermitted burst

Huge fragments vaulted like rebounding hail,

Or chaffy grain beneath the thresher’s flail:

And mid these dancing rocks at once and ever

It flung up momently the sacred river.

Five miles meandering with a mazy motion

Through wood and dale the sacred river ran,

Then reached the caverns measureless to man,

And sank in tumult to a lifeless ocean;

And ’mid this tumult Kubla heard from far

Ancestral voices prophesying war!

In Coleridge’s poem, which he subtitles “a vision in a dream,” Nature is all depth, but better to say that for Coleridge in “Kubla Khan” Nature is vital depth; Nature is a wellspring of robust and creative urgencies that is almost everywhere and almost at every moment alive. The exception would be the “lifeless ocean,” a symbol perhaps of what we now call entropy, but in a world of perpetual emergence even a “lifeless ocean” might be redeemed and revivified. Indeed, Coleridge in the quoted verses seems to be rescuing the etymon of the word nature, which is the same etymon that gave rise to the French verb naître, “to be born” or “to give birth.” The “chasm” gives birth to “a mighty fountain,” which in turn transforms itself into “a sacred river.” Coleridge’s endowment on the scenario of the term “sacred” reminds us that his Nature is not only vital, but hallowed or divine. The creative processes in nature point to a divine creative power beyond nature that reveals itself in phenomena and solicits from the sensitive soul the idea of something that requires a formal acknowledgment of its generative awesomeness.

Coleridge’s “caverns measureless to man” stand for the unplumbed depths not only of Nature but of the soul. To explore the hidden depths of Nature means also to explore the soul and vice versa. Coleridge draws on ancient conceptions that the Enlightenment claimed to have debunked, such as the conception of the psyche or soul, as articulated by the archaic philosopher-seer Heraclitus of Ephesus in one of his surviving aphorisms (No. 45): “You will not find out the limits of the soul when you go, travelling on every road, so deep a logos does it have.” Where the Enlightenment assumed that everything might be measured – that is to say, brought within the horizon of finite knowledge – Coleridge insists that the world possesses a “measureless” dimension that resists logical summary or reduction to purely quantitative or propositional terms. The only way to discuss such things is in symbol, imagery, and figure-of-speech.

Thomas Cole (1801-1848) The Catskills and Lake George, Catskill Creek, N.Y., 1845, oil on canvas.

A similar view of Nature as the source of vital energy necessary to the soul informs the final scene of Johann Wolfgang von Goethe’s Faust Part II (1831), where the errant sinner, Doctor Johann Faust, at last finds redemption from his graceless and degraded state. Goethe (1749 – 1832) sets his scene in primeval nature:

Waldung, sie schwankt heran,

Felsen, sie lasten dran,

Wurzeln, sie klammern an,

Stamm dicht an Stamm hinan,

Woge nach Woge spritzt,

Höhle, die tiefste, schützt.

Löwen, sie schleichen stumm-–

freundlich/ um uns herum,

Ehren geweihten Ort,

Heiligen Liebeshort.

[Forests, they wave around,

Over them, cliffs bear down,

Roots cling to rocky ground,

Trunk upon trunk is bound,

Wave after wave sprays up,

Deep caves protecting us.

Lions prowl silently,

Round us, still friendly,

Honouring sacred space,

Love’s holy hiding place.]

A few verses later, the character called Pater Profundis, who will play a mediating role in Faust’s redemption, utters these lines:

Wie Felsenabgrund mir zu Füßen

Auf tiefem Abgrund lastend ruht,

Wie tausend Bäche strahlend fließen

Zum grausen Sturz des Schaums der Flut,

Wie strack mit eignem kräftigen Triebe

Der Stamm sich in die Lüfte trägt:

So ist es die allmächtige Liebe,

Die alles bildet, alles hegt.

Ist um mich her ein wildes Brausen,

Als wogte Wald und Felsengrund,

Und doch stürzt, liebevoll im Sausen,

Die Wasserfülle sich zum Schlund,

Berufen, gleich das Tal zu wässern;

Der Blitz, der flammend niederschlug,

Die Atmosphäre zu verbessern,

Die Gift und Dunst im Busen trug –

Sind Liebesboten, sie verkünden,

Was ewig schaffend uns umwallt.

Mein Innres mög‘ es auch entzünden,

Wo sich der Geist, verworren, kalt,

Verquält in stumpfer Sinne Schranken,

Scharfangeschloßnem Kettenschmerz.

O Gott! beschwichtige die Gedanken,

Erleuchte mein bedürftig Herz!

[As this rocky abyss at my feet,

Rests on a deeper abyss,

As a thousand glittering streams meet

In the foaming flood’s downward hiss,

As with its own strong impulse, above,

The tree lifts skywards in the air:

Even so all-powerful love,

Creates all things, in its care.

Around me there’s a savage roar,

As if the rocks and forests sway,

Yet full of love the waters pour,

Rushing bountifully away,

Sent to irrigate the valley here:

The lightning that flashed down,

Must purify the atmosphere,

With poisonous vapours bound –

They are love’s messengers, they tell

Of what creates eternally around us.

May it inflame me inwardly, as well,

Since my spirit, cold and confounded,

Torments itself, bound in the dull senses,

As sharp-toothed fetters’ agonising art.

Oh, God! Calm my thoughts, pacify us,

And bring light to my needy heart!]

For Goethe as for Coleridge, Nature is the bourn of life, to which the afflicted soul might return to be nursed back to health. We recall that in Wordsworth’s sonnet “The world is too much with us,” the lyric subject feels exiled from nature and, in his attempt to rejoin with nature, catastrophically rebuffed. The world seems to him lifeless and still, and he also with it; he wants revivification. Faust seeks the same. Goethe’s “forests” answer him not in stillness, but make constantly a motion as they “wave around.” Just so, the “cliffs” actively “bear down” and “roots cling.” The dimension of depth goes not missing, for in Goethe’s scene “deep caves protect us” in a landscape thickly tangled (“trunk upon trunk”) that is “sacred” and, like some lonely place where a ritual purification might occur, hidden (“Love’s holy hiding place”) from profane eyes. When Pater Profundis (“The Father of the Depth”) begins to speak, he credits the landscape with “its own strong impulse.” The tree, straining its branches skyward, responds to the attractive principle of “Love” that serves Goethe for the equivalent of the non-anthropomorphic energy suffusing the caverns beneath Coleridge’s “stately pleasure dome” in “Kubla Khan.”

A poignant recurrence of this Coleridgean-Goethean constellation of ideas about Nature may be found in the work of the late John Michell (1933 – 2009), who referred to himself as a “Radical Traditionalist.” Readers know Michell best for his persistent work on the megalithic monuments of the European Neolithic Period, especially in Britain, which he demonstrated to have constituted a continental, and perhaps even a global, network whose builders intended them to help in keeping the dominion of man in contact with the dominion of the stars and of the deities that the stars betokened. Like Coleridge and Goethe, Michell posited a vital energy inherent in the earth, which the old stone circles and the long straight lines connecting them channeled and tapped. Michell possessed that conviction of a deep past antecedent to himself that distinguishes both Romanticism and Traditionalism from the modern default-state of “historylessness” and dogmatic materialism.

In The View over Atlantis (1969; revised as The New View over Atlantis, 1985), Michell writes how “of the various human and superhuman races that have occupied the earth in the past we have only the dreamlike accounts of the earliest myths, which tell of the magical powers of the ancients.” In his bold assertion, Michell echoes the prophecies of Blake, who revived the Old Plato’s “true myth” from the Timaeus in his epic poem America (1793). As in the Genesis-story of the Deluge or in Plato’s “Atlantis” story, Michell pieces together a narrative about “an overwhelming disaster of human or natural origin which destroyed a system whose maintenance depended upon its control of natural forces across the entire earth.” In one sense, Michell has simply reiterated that the Enlightenment happened, cutting across the lines of Tradition and depriving humanity of its proper heritage. For Michell, as for Blake or Wordsworth or Goethe, history is not the “account… of a recent ascent from bestiality and barbarism to the triumphs of modern civilization, but of a gradual, barely interrupted decline from the universal high culture of [Neolithic] antiquity to the present state of fragmentation and impending dissolution.”

IV. Romantic Nature Continued. Often for the Romantic poet, nature gives cover to secret activities that betoken an older world that in modern civic domains has given way to the despiritualizing forces of measure and logic – in the sociological process that some historians refer to as de-mystification. Nature is mysterious; she is the “magic forest” of the fairy-tales and legends, to enter which is perforce to run the risk of impish enthrallment or initiatory imperilment. In the pathways of the forest, man, in his ancient role as hunter, pursues wild game and, taking the prey, becomes one with it. The opening stanzas of “le Cor” (1826) by the French poet Alfred de Vigny (1797 – 1863) instantiate this variant of the Romantic Nature:

J’aime le son du Cor, le soir, au fond des bois,

Soit qu’il chante les pleurs de la biche aux abois,

Ou l’adieu du chasseur que l’écho faible accueille,

Et que le vent du nord porte de feuille en feuille.

Que de fois, seul, dans l’ombre à minuit demeuré,

J’ai souri de l’entendre, et plus souvent pleuré!

Car je croyais ouïr de ces bruits prophétiques

Qui précédaient la mort des Paladins antiques.

[I love the sounding horn, of an eve, deep within the woods,

Whether it sings the plaints of the threatened doe

Or the hunter’s retreat but faintly echoed

That the north wind carries from leaf to leaf.

[How often alone, in midnight shadows concealed,

I have smiled to hear it, even shedding a tear!

I thought to hear sounding prophetic plaints,

Declaring the death-knell for knights of old.]

As in Coleridge and Goethe, Nature in Vigny’s poetry offers herself as depth; she furnishes the paradoxically unapprehended scene of a ritual performance, which, however, the lyric subject can reconstitute in his imagination, provoked to the activity by the very sound. The horn-call reaches the lyric subject of Vigny’s poem from far away in the concealment of the woods, a place of half-light and shadows. The horn-call incites the lyric subject, as he says, to love: “I love the sounding of the horn, of an eve, deep within the woods.” But what is this “love”? It is precisely the awakened desire for the transcendent and unseen, for depth and distance; and it is a response to the sacred, mirrored in the desire of man for woman, and of the soul for beauty.

Note how in the first stanza of Vigny’s poem the sound of the horn mingles with the rustling of the north wind, as though the two timbres had become one and therefore indistinguishable. In the second stanza, the horn-call comes to resemble “prophetic plaints, / declaring the death-knell for knights of old.” Not only the reunion of culture and nature, which have become alienated from one another, but also whole extinct worlds of medieval pageantry and hieratic drama, lie concealed in oaken and beechy precincts. Let it be noted finally, in passing, how Vigny’s “Cor” with its “prophetic plaints” makes a parallelism with Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan,” where “ancestral voices” are “prophesying war.”

“Goethe in the Roman Campagna,” 1786, by Johann Heinrich Wilhelm Tischbein, oil on canvas.

What do the scholars say about the Romantic view of landscape and nature? François-René Chateaubriand (1768 – 1848), a second-generation French Romantic who was also one of the early scholars of Romanticism, writes in his great study of The Genius of Christianity (1802) concerning the distinction between ancient and modern poetry that “mythology… circumscribed the limits of nature and banished truth from her domain.” In modern poetry, by which Chateaubriand means Christian poetry: “The deserts have assumed a character more pensive, more vague, and more sublime; the forests have attained a loftier pitch; the rivers have broken their pretty urns, that in future they may only pour the waters of the abyss from the summit of the mountains; and the true God, in returning to his works, has imparted his immensity to nature.” Chateaubriand associates paganism with naturalism – that is to say, with the taxonomic or classifying study of natural phenomena, as exemplified in the work of Pliny the Younger. Chateaubriand thus opposes the Romantic or Christian view of Nature against the Classical or Pagan view of nature, which had been taken up again by the Enlightenment, favoring the former over the latter.

If, as Chateaubriand writes, “the prospect of the universe [excited not] in the bosoms of the Greeks and Romans those emotions which it produces in our souls,” then it follows that the Enlightenment mentality, surveying the same “prospect,” would come away from the encounter as affectively blank as did the Epicurean precursor whose view Eighteenth-Century Classicism has reinvented. The modern poet in confronting the universe, according to Chateaubriand, enjoys the differentiating privilege to “taste the fullness of joy in the presence of its Author.” It is true that there is no Pagan equivalent of the Fall-from-Grace. Because consciousness is equivalent to recollection, and because paganism never experienced Nature as lost, the Christian sense of Nature must exceed the Pagan sense in both quality and intensity. Christianity is a return to nature or a recovery of it, a homecoming, as it were, with all the poignancy thereof.

In Natural Supernaturalism (1973), one of the great studies of the Romantic Movement, and with specific reference to Wordsworth, M. H. Abrams (born 1912 – still living) writes that for the Grasmere poet “Scriptural Apocalypse is assimilated to an apocalypse of nature [whose] written characters are natural objects, which [the poet reads] as types and symbols of permanence in change.” Abrams shows in his study how Wordsworth in particular and the Romantics in general inherited from Edmund Burke and German idealism the aesthetic dichotomy of The Beautiful and the Sublime. The Beautiful is whatever is picturesque, pleasing, and amiable in Nature. The Sublime is whatever is awesome, threatening, and grandiose in Nature. In communing with Nature, the sensitive soul finds in Beauty the stepping-stone to the Sublime, and it is in the Sublime that he reads – or has read to him – the real lesson of Nature. Abrams writes that the “antithetic qualities of sublimity and beauty are seen [by the poet] as simultaneous expressions on the face of heaven and earth, declaring an unrealized truth which the chiaroscuro of the scene articulates for the [properly] prepared mind – a truth about the darkness and the light, the terror and the peace, the ineluctable contraries that make up our human existence.”

In American Sublime: Landscape Painting in the United States, 1820 – 1880 (2002), Andrew Wilton and Tim Barringer comment on the centrality of the Sublime in the Romantic conception of landscape. “The Sublime,” they write, “incorporated a further dimension [namely that] the imagination has an important part to play in our perception of what is immense, nebulous, beyond exact description.” When the percipient discovers “spiritual significance in nature,” he is not making a passive observation; on the contrary, he is participating in the constitution of such significance. Writing of Frederic Church’s panorama in oils of Niagara (1857), Wilton and Barringer remark that, “it is not a meditation on light, but on the power of nature manifested in the grandest geographical phenomena.” They go on to remark that “Church conceived [Niagara] as a show-piece, a masterpiece in the original sense: a specimen of his own powers at their most impressive – a match, perhaps, in a consciously humble way, to God’s own.” Church’s canvass also communicates with the “abyss” of Coleridge’s “Kubla Khan,” a metaphor of the soul and of the psychic component of the universe as “measureless to man.”

V. Traditionalism as the New Phase of Romanticism. Abrams’ attribution to Wordsworth of a sense of Nature as “apocalyptic” applies equally well to Church (1826 – 1900), for whom the great cataract, directly on the brink of which his painting positions the viewer, is also “apocalyptic” – God revealing His greatness through the sublimity of the falling waters, the magnificent roar, and the rearing luminous mists. Church painted a number of scenes that would have pleased Michell, such as his “Aegean Sea” (1877), with its ancient ruins, including the half-hidden entrance to a cave-shrine, against a brilliantly light island-harbor with mists and rainbows. Church’s “Cross in the Wilderness” (1857), with its rugged mountains and faraway, luminous horizon, implies a Chateaubriand-like grasp of the religious struggle, with its concluding vision, as the essentially human struggle. It probably implies Michell’s ley-lines and megalithic power-foci. The Hudson River School of painting, to which Church belonged, was a thoroughly Romantic phenomenon, motivated by an awareness of the disappearing wilderness, which it sought to record, and dedicated to the ideal that civilization must never violate the natural order; that humbleness before the sublimity of the natural world is the proper attitude for civilized people to assume.

The Lake Poets in England and the Hudson River painters in North America feared the tendencies of their era – the spread of callous industrialism, the aggrandizement of cities, the blighting of the countryside, and the coarsening of the soul. They warned against these trends even as it became evident that the trends would overwhelm any critique. The Lake Poets eventually came to grasp that their philosophical and aesthetic convictions implied a politics. Wordsworth and Coleridge became Tories, or as Americans would say, conservatives. Vigny and Chateaubriand were also on the right, the former describing himself as the sole male survivor of a parental generation that the Revolution had eaten alive. These men would better be described, however, as reactionaries – against the encroachments of the Reign of Quantity and the pseudo-ethos of “getting and spending” – and as Traditionalists: Defenders and conservators of the local against the metropolitan, of dialect against rhetoric, and of the spirit against a prescriptively and intolerantly materialist view of life and the world. Their opposite numbers were the propagandists for the insidious synergy of the laborites and socialists with the bankers and industrialists.

In The Communist Manifesto (1848), Karl Marx (1818 – 1883) and Frederick Engels (1820 – 1895) condemn the bourgeoisie, whom they propose to abolish, but they extol the “subjection of Nature’s forces to man, machinery, application of chemistry to industry and agriculture, steam-navigation, railways, electric telegraphs, clearing of whole continents for cultivation, canalisation of rivers, whole populations conjured out of the ground” that “Capitalism,” the project of the bourgeoisie, had created. Marx, as much as the industrialists, looked forward to the “extension of factories and instruments of production owned by the State; the bringing into cultivation of waste-lands, and the improvement of the soil generally in accordance with a common plan” and to the “establishment of industrial armies, especially for agriculture.” Scots poet Robert Burns (1759 – 1796) had already indicted the right riposte in his “Impromptu on the Carron iron Works” (1787):

We cam na here to view your warks,

In hopes to be mair wise,

But only, lest we gang to hell,

It may be nae surprise:

But when we tirl’d at your door

Your porter dought na hear us;

Sae may, shou’d we to Hell’s yetts come,

Your billy Satan sair us!

In the prevailing situation in the second decade of the Twenty-First Century, the literature professors prefer denouncing the Romantic poets to understanding them, and the art-history professors regard the Hudson River painters as “illustrators” who could not possibly have believed in the Transcendentalist or spiritualist doctrines that they expounded. Prophets of modern thought like Theodore Wiesengrund Adorno (1903 – 1969) and Jacques Derrida (1930 – 2004) have, of course, conclusively demonstrated that all Lake Poets and all Hudson River painters, even the ones who were Unitarians hence half-way to being modern liberals, were and remain servitors of false consciousness and an oppressive “logocentrism,” from which everyone should be compulsorily liberated. In the colleges and universities, the Cultural-Marxist hatred for anything not Cultural-Marxist grows red-hot, white-hot, and ultraviolet-hot by swift stages. That is a metonymy of exactly what the early twentieth-Century Traditionalists predicted.

In The End of Our Time (1933), Berdyaev argues that, “The Renaissance began with the affirmation of man’s creative individuality; it has ended with its denial.” Creativity, which Michelangelo and J. S, Bach ascribed to God, produces unequal results that inspire “envy,” which in turn solicits a demand for “equality.” For Berdyaev, the principle of modernity is “envy of the being of another and bitterness at the inability to affirm one’s own.” Thus, according to Berdyaev’s analysis, “Our age is like to that which saw the passing of the ancient world” although “that was the passing of a culture incomparably finer than the culture of today.” It is possible, writes Berdyaev, to “trace the ruin of the Renaissance in modernist art, in Futurism, in philosophy, in Critical Gnoseology… and finally in socialism and anarchism,” all of which begin with a rejection of Romantic, and therefore of religious, values.

In The Meaning of the Creative Act (1916), Berdyaev, contrasting “Canonic” or “pagan” art with “Christian art, or, better, the art of the Christian epoch,” arrives at the dichotomy that “pagan art is classic and immanent” where “Christian art is romantic… and transcendent.” The parallelism between Berdyaev and Chateaubriand will be abundantly self-evident. As Berdyaev sees it, “In [the] classically beautiful perfection of form [in] the pagan world there is no upsurge towards another world… no abyss… above or below”; that is, no “caverns measureless to man.” The Romantic, knowing that he can never achieve perfection in this world, shies from utopian projects that inevitably become coercive and universal. Thus “a romantic incompleteness… characterizes Christian art,” which takes as a premise, among others, the conviction “that final, perfect, eternal beauty is possible only in another world.” That the Romantic often succumbs to the frustration inherent in eternal longing, Berdyaev notes; but the Romantics themselves knew their vulnerability in this regard well and were wont candidly to diagnose it, as Wordsworth does in “The world is too much with us,” candidly. Berdyaev saw in Nineteenth-Century Romanticism the last pause in the steady descent of the Western world into materialism, utilitarianism, and nihilism, the equivalent of Guénon’s Kali Yuga or Dark Age.

Contemporary Traditionalism picks up where Berdyaev, Guénon, and the mid-Twentieth Century anti-modernists, and again where the Romantics, in their century, left off. Traditionalists recognize that the critical situation of their time is deeper, more degraded, more irremediably catastrophic than the of one hundred or one hundred-and-fifty years ago, but they also see that it is the same crisis and that if the Endarkenment of their day were more acute by a magnitude at least than it was in 1820 or 1920 it would also be closer to its irrevocable finale. The problem for Traditionalists is how severe that finale will be. Will it conform itself to the Foundering of Atlantis or the Fall of Rome? The former constituted a choke-point after which civilized life had to begin again from the degree zero. The latter sacrificed the Imperial infrastructure, both physical and bureaucratic, for the reorientation of Western European humanity from the Mediterranean to the Atlantic. The Greeks and Romans feared to sail beyond the Pillars of Hercules. Significantly, the conquest of the Atlantic and the opening up of North America fell to those Northwestern Goths, the Vikings, at the very moment when Iceland was embracing Christianity. Leif Erikson was an early convert, as was Thorfinn Karlsefni.

Modernity is a Polyphemus, an angry unison-chorus, shouting like thunder that man is the measure and that there is nothing, not measurable by man. Traditionalism is the quiet voice, seeking parlay with other hushed voices, so that together they might enter conversation with the Forest Murmurs and even the distant Music of the Spheres and come to know better what they already suspect, that man must begin by measuring himself against the measureless.

[This essay is dedicated to Professors Cocks and Presley and to “The Two Scholars.”]

Thomas F. Bertonneau earned a Ph.D. in Comparative Literature from the University of Califonia at Los Angeles in 1990. He has taught at a variety of institutions, and has been a member of the English Faculty at SUNY Oswego since 2001. He is the author of three books and numerous articles on literature, art, music, religion, anthropology, film, and politics. He is a frequent contributor to Anthropoetics, the ISI quarterlies, and others.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Perché i Greci non possiedono nel loro lessico una parola per dire “corpo”? Perché non possiedono una parola per dire “materia”? Ed affermano che essa come tale non esiste? (1) Perché quando parlano di “corpo” si riferiscono al “soma” cioè al “cadavere”? Fanno riferimento quindi al “corpo” senza vita, senza funzione, senza pensiero, sentimenti, coraggio, personalità, senza “Io” nel significato omerico (arcaico) e quindi tradizionalmente ellenico, come complesso multivocale e multifunzionale, ancorché unitario (2), di potenze della Vita simili a quelle cosmiche (gli Dei). Fanno riferimento pertanto ad un non-ente, ad un “niente”.

Perché i Greci non possiedono nel loro lessico una parola per dire “corpo”? Perché non possiedono una parola per dire “materia”? Ed affermano che essa come tale non esiste? (1) Perché quando parlano di “corpo” si riferiscono al “soma” cioè al “cadavere”? Fanno riferimento quindi al “corpo” senza vita, senza funzione, senza pensiero, sentimenti, coraggio, personalità, senza “Io” nel significato omerico (arcaico) e quindi tradizionalmente ellenico, come complesso multivocale e multifunzionale, ancorché unitario (2), di potenze della Vita simili a quelle cosmiche (gli Dei). Fanno riferimento pertanto ad un non-ente, ad un “niente”. Inoltre Platone, tra le fenomenologie della “mania”, pur non indicando la forma guerriera, fa riferimento a quella erotica, a quella poetica come alla mantica, tutte molto simili alla Via Ultrasecca che è, per l’appunto, la Via del guerriero (vedi il concetto di “ménos” in Omero come “follia” e quello di “furor” nella cultura romana). (3)

Inoltre Platone, tra le fenomenologie della “mania”, pur non indicando la forma guerriera, fa riferimento a quella erotica, a quella poetica come alla mantica, tutte molto simili alla Via Ultrasecca che è, per l’appunto, la Via del guerriero (vedi il concetto di “ménos” in Omero come “follia” e quello di “furor” nella cultura romana). (3)

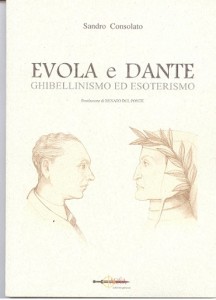

Rispetto all’interesse evoliano per il dato esoterico-politico nell’Alighieri, è opportuno ricordare che la cerca del Poeta è sintonica, e la cosa è accortamente rilevata da Consolato, a quella che maturò negli ambienti graalici in rapporto al problema dell’Impero. Caratterizzata, in particolare, dal continuo riferirsi al motivo dell’imperatore latente, mai morto e per questo atteso e al Regno isterilito, simbolizzato in modo paradigmatico dall’Albero secco che rinverdirà con il rimanifestarsi nella storia dell’Impero, per l’azione del Veltro-Dux. L’Impero, per esser tale, deve far riferimento ad un re-sacerdote il cui modello è Melchisedec, custode della funzione attiva e di quella contemplativa. L’autore suggerisce che in tema di Veltro e relativamente alla sua esegesi storico-politica, Evola si richiama alla lezione di Alfred Bassermann, grazie alla quale egli coglie come Dante, in tema, si sia fermato a metà strada, “la sua concezione dei rapporti tra Chiesa e Impero rimase imperniata su di un dualismo limitatore…tra vita contemplativa e vita attiva” (p. 39). Lo stesso esoterismo dell’Alighieri era legato ad una sorta di via iniziatica platonizzante, non pienamente giunta a rilevare, come accadrà nel puro templarismo, che l’iniziazione regale risolve in sé i due momenti del Principio, contemplazione ed azione. In questo contesto, suggerisce Consolato, deve essere letta la polemica di Cecco d’Ascoli nei confronti dell’Alighieri, attaccato in quanto “deviazionista” rispetto all’iniziazione propriamente regale. In questi termini, Dante è il simbolo più proprio, per Evola, dell’età in cui visse, il

Rispetto all’interesse evoliano per il dato esoterico-politico nell’Alighieri, è opportuno ricordare che la cerca del Poeta è sintonica, e la cosa è accortamente rilevata da Consolato, a quella che maturò negli ambienti graalici in rapporto al problema dell’Impero. Caratterizzata, in particolare, dal continuo riferirsi al motivo dell’imperatore latente, mai morto e per questo atteso e al Regno isterilito, simbolizzato in modo paradigmatico dall’Albero secco che rinverdirà con il rimanifestarsi nella storia dell’Impero, per l’azione del Veltro-Dux. L’Impero, per esser tale, deve far riferimento ad un re-sacerdote il cui modello è Melchisedec, custode della funzione attiva e di quella contemplativa. L’autore suggerisce che in tema di Veltro e relativamente alla sua esegesi storico-politica, Evola si richiama alla lezione di Alfred Bassermann, grazie alla quale egli coglie come Dante, in tema, si sia fermato a metà strada, “la sua concezione dei rapporti tra Chiesa e Impero rimase imperniata su di un dualismo limitatore…tra vita contemplativa e vita attiva” (p. 39). Lo stesso esoterismo dell’Alighieri era legato ad una sorta di via iniziatica platonizzante, non pienamente giunta a rilevare, come accadrà nel puro templarismo, che l’iniziazione regale risolve in sé i due momenti del Principio, contemplazione ed azione. In questo contesto, suggerisce Consolato, deve essere letta la polemica di Cecco d’Ascoli nei confronti dell’Alighieri, attaccato in quanto “deviazionista” rispetto all’iniziazione propriamente regale. In questi termini, Dante è il simbolo più proprio, per Evola, dell’età in cui visse, il

Celui qui l’a appris à ses dépens, c’est un Néo-Zélandais, gérant de bar en Birmanie (Myanmar, SVP), un certain Phil Blackwood, condamné à deux ans et demi de prison pour avoir portraituré Bouddha avec des écouteurs sur la tête, juste histoire de faire de la publicité pour son bar, « lounge », évidemment. Eh oui, le bouddhisme, ce n’est pas forcément la fête du slip tous les dimanches. Le Phil Blackwood en question a eu beau s’excuser, battre coulpe et montrer patte blanche : pas de remise de peine et case prison direct.

Celui qui l’a appris à ses dépens, c’est un Néo-Zélandais, gérant de bar en Birmanie (Myanmar, SVP), un certain Phil Blackwood, condamné à deux ans et demi de prison pour avoir portraituré Bouddha avec des écouteurs sur la tête, juste histoire de faire de la publicité pour son bar, « lounge », évidemment. Eh oui, le bouddhisme, ce n’est pas forcément la fête du slip tous les dimanches. Le Phil Blackwood en question a eu beau s’excuser, battre coulpe et montrer patte blanche : pas de remise de peine et case prison direct. Le penseur français René Guénon (1886 – 1957) ne suscite que très rarement l’intérêt de l’université hexagonale. On doit par conséquent se réjouir de la sortie de René Guénon. Une politique de l’esprit par David Bisson. À l’origine travail universitaire, cet ouvrage a été entièrement retravaillé par l’auteur pour des raisons d’attraction éditoriale évidente. C’est une belle réussite aidée par une prose limpide et captivante.

Le penseur français René Guénon (1886 – 1957) ne suscite que très rarement l’intérêt de l’université hexagonale. On doit par conséquent se réjouir de la sortie de René Guénon. Une politique de l’esprit par David Bisson. À l’origine travail universitaire, cet ouvrage a été entièrement retravaillé par l’auteur pour des raisons d’attraction éditoriale évidente. C’est une belle réussite aidée par une prose limpide et captivante. Au cours de l’Entre-deux-guerres, le futur historien des religions affine sa propre vision du monde. Alimentant sa réflexion d’une immense curiosité pluridisciplinaire, il a lu – impressionné – les écrits de Guénon. D’abord rétif à tout militantisme politique, Eliade se résout sous la pression de ses amis et de son épouse à participer au mouvement politico-mystique de Corneliu Codreanu. Il y devient alors une des principales figures intellectuelles et y rencontre un nommé Cioran. Au sein de cet ordre politico-mystique, Eliade propose un « nationalisme archaïque (p. 252) » qui assigne à la Roumanie une vocation exceptionnelle. Son engagement dans la Garde de Fer ne l’empêche pas de mener une carrière de diplomate qui se déroule en Grande-Bretagne, au Portugal et en Allemagne. Son attrait pour les « mentalités primitives » et les sociétés traditionnelles pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale s’accroît si bien qu’exilé en France après 1945, il jette les premières bases de l’histoire des religions qui le feront bientôt devenir l’universitaire célèbre de Chicago. Si Eliade s’éloigne de Guénon et ne le cite jamais, David Bisson signale cependant qu’il lui expédie ses premiers ouvrages. En retour, ils font l’objet de comptes-rendus précis. Bisson peint finalement le portrait d’un Mircea Eliade louvoyant, désireux de faire connaître et de pérenniser son œuvre.

Au cours de l’Entre-deux-guerres, le futur historien des religions affine sa propre vision du monde. Alimentant sa réflexion d’une immense curiosité pluridisciplinaire, il a lu – impressionné – les écrits de Guénon. D’abord rétif à tout militantisme politique, Eliade se résout sous la pression de ses amis et de son épouse à participer au mouvement politico-mystique de Corneliu Codreanu. Il y devient alors une des principales figures intellectuelles et y rencontre un nommé Cioran. Au sein de cet ordre politico-mystique, Eliade propose un « nationalisme archaïque (p. 252) » qui assigne à la Roumanie une vocation exceptionnelle. Son engagement dans la Garde de Fer ne l’empêche pas de mener une carrière de diplomate qui se déroule en Grande-Bretagne, au Portugal et en Allemagne. Son attrait pour les « mentalités primitives » et les sociétés traditionnelles pendant la Seconde Guerre mondiale s’accroît si bien qu’exilé en France après 1945, il jette les premières bases de l’histoire des religions qui le feront bientôt devenir l’universitaire célèbre de Chicago. Si Eliade s’éloigne de Guénon et ne le cite jamais, David Bisson signale cependant qu’il lui expédie ses premiers ouvrages. En retour, ils font l’objet de comptes-rendus précis. Bisson peint finalement le portrait d’un Mircea Eliade louvoyant, désireux de faire connaître et de pérenniser son œuvre. En étroite correspondance épistolaire avec Guénon, Schuon devient son « fils spirituel ». cela lui permet de recruter de nouveaux membres pour sa confrérie soufie qu’il développe en Europe. D’abord favorable à son islamisation, Schuon devient ensuite plus nuancé, « la forme islamique ne contrevenant, en aucune manière, à la dimension chrétienne de l’Europe. Il essaiera même de fondre les deux perspectives dans une approche universaliste dont l’ésotérisme sera le vecteur (p. 172) ». Cette démarche syncrétiste s’appuie dès l’origine sur son nom musulman signifiant « Jésus, Lumière de la Tradition».

En étroite correspondance épistolaire avec Guénon, Schuon devient son « fils spirituel ». cela lui permet de recruter de nouveaux membres pour sa confrérie soufie qu’il développe en Europe. D’abord favorable à son islamisation, Schuon devient ensuite plus nuancé, « la forme islamique ne contrevenant, en aucune manière, à la dimension chrétienne de l’Europe. Il essaiera même de fondre les deux perspectives dans une approche universaliste dont l’ésotérisme sera le vecteur (p. 172) ». Cette démarche syncrétiste s’appuie dès l’origine sur son nom musulman signifiant « Jésus, Lumière de la Tradition». Mais qu’est-ce que la multipolarité ? Pour Alexandre Douguine, ce phénomène « procède d’un constat : l’inégalité fondamentale entre les États-nations dans le monde moderne, que chacun peut observer empiriquement. En outre, structurellement, cette inégalité est telle que les puissances de deuxième ou de troisième rang ne sont pas en mesure de défendre leur souveraineté face à un défi de la puissance hégémonique, quelle que soit l’alliance de circonstance que l’on envisage. Ce qui signifie que cette souveraineté est aujourd’hui une fiction juridique (pp. 8 – 9) ». « La multipolarité sous-tend seulement l’affirmation que, dans le processus actuel de mondialisation, le centre incontesté, le noyau du monde moderne (les États-Unis, l’Europe et plus largement le monde occidental) est confronté à de nouveaux concurrents, certains pouvant être prospères voire émerger comme puissances régionales et blocs de pouvoir. On pourrait définir ces derniers comme des “ puissances de second rang ”. En comparant les potentiels respectifs des États-Unis et de l’Europe, d’une part, et ceux des nouvelles puissances montantes (la Chine, l’Inde, la Russie, l’Amérique latine, etc.), d’autre part, de plus en plus nombreux sont ceux qui sont convaincus que la supériorité traditionnelle de l’Occident est toute relative, et qu’il y a lieu de s’interroger sur la logique des processus qui déterminent l’architecture globale des forces à l’échelle planétaire – politique, économie, énergie, démographie, culture, etc. (p. 5) ». Elle « implique l’existence de centres de prise de décision à un niveau relativement élevé (sans toutefois en arriver au cas extrême d’un centre unique, comme c’est aujourd’hui le cas dans les conditions du monde unipolaire). Le système multipolaire postule également la préservation et le renforcement des particularités culturelles de chaque civilisation, ces dernières ne devant pas se dissoudre dans une multiplicité cosmopolite unique (p. 17) ». Le philosophe russe s’inspire de certaines thèses de l’universitaire réaliste étatsunien, Samuel Huntington. Tout en déplorant les visées atlantistes et occidentalistes, l’eurasiste russe salue l’« intuition de Huntington qui, en passant des États-nations aux civilisations, induit un changement qualitatif dans la définition de l’identité des acteurs du nouvel ordre mondial (p. 96) ».

Mais qu’est-ce que la multipolarité ? Pour Alexandre Douguine, ce phénomène « procède d’un constat : l’inégalité fondamentale entre les États-nations dans le monde moderne, que chacun peut observer empiriquement. En outre, structurellement, cette inégalité est telle que les puissances de deuxième ou de troisième rang ne sont pas en mesure de défendre leur souveraineté face à un défi de la puissance hégémonique, quelle que soit l’alliance de circonstance que l’on envisage. Ce qui signifie que cette souveraineté est aujourd’hui une fiction juridique (pp. 8 – 9) ». « La multipolarité sous-tend seulement l’affirmation que, dans le processus actuel de mondialisation, le centre incontesté, le noyau du monde moderne (les États-Unis, l’Europe et plus largement le monde occidental) est confronté à de nouveaux concurrents, certains pouvant être prospères voire émerger comme puissances régionales et blocs de pouvoir. On pourrait définir ces derniers comme des “ puissances de second rang ”. En comparant les potentiels respectifs des États-Unis et de l’Europe, d’une part, et ceux des nouvelles puissances montantes (la Chine, l’Inde, la Russie, l’Amérique latine, etc.), d’autre part, de plus en plus nombreux sont ceux qui sont convaincus que la supériorité traditionnelle de l’Occident est toute relative, et qu’il y a lieu de s’interroger sur la logique des processus qui déterminent l’architecture globale des forces à l’échelle planétaire – politique, économie, énergie, démographie, culture, etc. (p. 5) ». Elle « implique l’existence de centres de prise de décision à un niveau relativement élevé (sans toutefois en arriver au cas extrême d’un centre unique, comme c’est aujourd’hui le cas dans les conditions du monde unipolaire). Le système multipolaire postule également la préservation et le renforcement des particularités culturelles de chaque civilisation, ces dernières ne devant pas se dissoudre dans une multiplicité cosmopolite unique (p. 17) ». Le philosophe russe s’inspire de certaines thèses de l’universitaire réaliste étatsunien, Samuel Huntington. Tout en déplorant les visées atlantistes et occidentalistes, l’eurasiste russe salue l’« intuition de Huntington qui, en passant des États-nations aux civilisations, induit un changement qualitatif dans la définition de l’identité des acteurs du nouvel ordre mondial (p. 96) ». Piochant dans toutes les écoles théoriques existantes, le choix multipolaire de Douguine n’est au fond que l’application à un domaine particulier – la géopolitique – de ce qu’il nomme la « Quatrième théorie politique ». Titre d’un ouvrage essentiel, cette nouvelle pensée politique prend acte de la victoire de la première théorie politique, le libéralisme, sur la deuxième, le communisme, et la troisième, le fascisme au sens très large, y compris le national-socialisme.

Piochant dans toutes les écoles théoriques existantes, le choix multipolaire de Douguine n’est au fond que l’application à un domaine particulier – la géopolitique – de ce qu’il nomme la « Quatrième théorie politique ». Titre d’un ouvrage essentiel, cette nouvelle pensée politique prend acte de la victoire de la première théorie politique, le libéralisme, sur la deuxième, le communisme, et la troisième, le fascisme au sens très large, y compris le national-socialisme.

La testimonianza archeologica che più può essere d’aiuto per comprendere il complesso sistema iniziatico del culto di Mithra è sicuramente il mosaico pavimentale presente nel mitreo di Felicissimo ad Ostia, denominato Scala delle Sette Porte. Sia Celso sia Porfirio ci parlano di un’iniziazone con sette diversi e gerarchici gradi di conoscenza e, come rappresentato nelle sette porte di Ostia, ognuno rappresentato dall’animale simbolico e dall’Astro/Nume di riferimento. Il primo grado è rappresentato dal Corax (Corvo), egli è la base del culto mithriaco, il neofita che affronta le prime prove di umiltà, di controllo dell’ego, di mantenimento del segreto. Simboleggiato appunto da un corvo, è il messaggero degli Dei che risvegliano Mithra, avendo in Hermes-Mercurio la propria divinità tutelare. Il risveglio è l’inizio della rettificazione del myste, il risveglio della propria essenza solare: ogni rettificazione la si può riconnettere ai centri di luce, chakra nella tradizione indù o sephira in quella cabalistica, lungo il canale verticale che corre lungo la colonna vertebrale, espressione proprio di un Caduceo Ermetico che ritroviamo tra i simboli di Hermes e del Corax, ove si intrecciano le energie lunari e solari, mercuriali e sulfuree, lungo quello che viene denominato il “canale di Brahma”.

La testimonianza archeologica che più può essere d’aiuto per comprendere il complesso sistema iniziatico del culto di Mithra è sicuramente il mosaico pavimentale presente nel mitreo di Felicissimo ad Ostia, denominato Scala delle Sette Porte. Sia Celso sia Porfirio ci parlano di un’iniziazone con sette diversi e gerarchici gradi di conoscenza e, come rappresentato nelle sette porte di Ostia, ognuno rappresentato dall’animale simbolico e dall’Astro/Nume di riferimento. Il primo grado è rappresentato dal Corax (Corvo), egli è la base del culto mithriaco, il neofita che affronta le prime prove di umiltà, di controllo dell’ego, di mantenimento del segreto. Simboleggiato appunto da un corvo, è il messaggero degli Dei che risvegliano Mithra, avendo in Hermes-Mercurio la propria divinità tutelare. Il risveglio è l’inizio della rettificazione del myste, il risveglio della propria essenza solare: ogni rettificazione la si può riconnettere ai centri di luce, chakra nella tradizione indù o sephira in quella cabalistica, lungo il canale verticale che corre lungo la colonna vertebrale, espressione proprio di un Caduceo Ermetico che ritroviamo tra i simboli di Hermes e del Corax, ove si intrecciano le energie lunari e solari, mercuriali e sulfuree, lungo quello che viene denominato il “canale di Brahma”.  Il terzo grado è quello del Miles (Soldato), simboleggiato dallo scorpione, rappresenta, tramite la consacrazione a Mithra ed il rifiuto dell’incoronazione umana (“Mithra è la mia corona!”), l’ingresso dell’iniziato nella Milizia Celeste, coloro che combattono per il Fuoco e la Luce, avendo in Marte il proprio nume tutelare. E’ il chakra Manipura dove ha sede il fuoco, in corrispondenza con il plesso solare, o l’ottavo sephira Hod, la sapienza e la collettività, quindi Mithra che esce armato dalla grotta platonica per combattere, con la lancia di Marte, per affrontare un cammino oscuro che non conosce, è l’elemento ferreo che si attiva, l’irrazionale che cerca di purificarsi, la forza guerriera cieca, istintiva, che intraprende la via per la propria purificazione: alchemicamente si arriva alla terza operazione, quella della soluzione, ove si produce l’unione progressiva e non violenta del fisso col volatile…il Fuoco deve essere ancor tenuto basso!

Il terzo grado è quello del Miles (Soldato), simboleggiato dallo scorpione, rappresenta, tramite la consacrazione a Mithra ed il rifiuto dell’incoronazione umana (“Mithra è la mia corona!”), l’ingresso dell’iniziato nella Milizia Celeste, coloro che combattono per il Fuoco e la Luce, avendo in Marte il proprio nume tutelare. E’ il chakra Manipura dove ha sede il fuoco, in corrispondenza con il plesso solare, o l’ottavo sephira Hod, la sapienza e la collettività, quindi Mithra che esce armato dalla grotta platonica per combattere, con la lancia di Marte, per affrontare un cammino oscuro che non conosce, è l’elemento ferreo che si attiva, l’irrazionale che cerca di purificarsi, la forza guerriera cieca, istintiva, che intraprende la via per la propria purificazione: alchemicamente si arriva alla terza operazione, quella della soluzione, ove si produce l’unione progressiva e non violenta del fisso col volatile…il Fuoco deve essere ancor tenuto basso!  L’esame del settimo grado dell’iniziazione mithriaca, quello del Pater, comporta necessariamente un approfondimento del mito centrale e fondante del culto in questione, cioè il sacrificio cosmogonico ed esoterico del toro: tale mito, insieme alla tutela mithriaca dei patti e dei giuramenti, è sicuramente presente sin dall’origini indoiraniche della divinità e ne rappresenta simbolicamente la più alta valenza metafisica. Mithra nato dalla roccia il giorno del Solstizio d’Inverno e uscito dalla caverna nel grado di Miles, sa di dover immolare il toro, per ordine degli Dei su mandato del loro messaggero, il corvo Hermes-Mercurio.

L’esame del settimo grado dell’iniziazione mithriaca, quello del Pater, comporta necessariamente un approfondimento del mito centrale e fondante del culto in questione, cioè il sacrificio cosmogonico ed esoterico del toro: tale mito, insieme alla tutela mithriaca dei patti e dei giuramenti, è sicuramente presente sin dall’origini indoiraniche della divinità e ne rappresenta simbolicamente la più alta valenza metafisica. Mithra nato dalla roccia il giorno del Solstizio d’Inverno e uscito dalla caverna nel grado di Miles, sa di dover immolare il toro, per ordine degli Dei su mandato del loro messaggero, il corvo Hermes-Mercurio.  Molti sono stati gli scritti, gli articoli, i testi che profondamente hanno indagato la simbolica e l’essenza tradizionale e spirituale dell’iniziazione mithriaca, ma, purtroppo, pochi hanno ben evidenziato come il settimo grado di tale culto misterico, quello del Pater, non rappresentasse l’ultima tappa dell’ascensione al Divino. Se profanamente si provasse a schematizzare il processo iniziatico di cui si è scritto, sarebbe possibile confrontarlo, riducendo il settenario in forma quaternaria, alle varie fasi dell’Opera Alchemica ed alla suddivisione microcosmica operata dal Kremmerz e dalla sua Schola. Infatti, le prime quattro figure che partono dal Corax ed arrivano al Leone è possibile paragonarle alle quattro operazioni dell’Opera al Nero, la Nigredo (calcinazione, putrefazione, soluzione, distillazione ), mentre la figura del Pherses, sotto l’egida astrale della Luna, e quella di Heliodromos, portatore del Sole ma non il Sole, configurano la dimensione numinosa della nuda Diana, dell’immortalità virtuale, quindi della realizzazione dell’Opera al Bianco, Albedo.

Molti sono stati gli scritti, gli articoli, i testi che profondamente hanno indagato la simbolica e l’essenza tradizionale e spirituale dell’iniziazione mithriaca, ma, purtroppo, pochi hanno ben evidenziato come il settimo grado di tale culto misterico, quello del Pater, non rappresentasse l’ultima tappa dell’ascensione al Divino. Se profanamente si provasse a schematizzare il processo iniziatico di cui si è scritto, sarebbe possibile confrontarlo, riducendo il settenario in forma quaternaria, alle varie fasi dell’Opera Alchemica ed alla suddivisione microcosmica operata dal Kremmerz e dalla sua Schola. Infatti, le prime quattro figure che partono dal Corax ed arrivano al Leone è possibile paragonarle alle quattro operazioni dell’Opera al Nero, la Nigredo (calcinazione, putrefazione, soluzione, distillazione ), mentre la figura del Pherses, sotto l’egida astrale della Luna, e quella di Heliodromos, portatore del Sole ma non il Sole, configurano la dimensione numinosa della nuda Diana, dell’immortalità virtuale, quindi della realizzazione dell’Opera al Bianco, Albedo.

El Islam, en cambio, incluso en nuestras sociedades, a menudo trae elementos y valores realmente incompatibles con la modernidad y, por lo tanto, difícilmente “integrables”. Y es eso lo que las fuerzas identitarias le reprochan, viendo a sus miembros como sujetos extraños y alógenos respecto a nuestro mundo, a diferencia, como se ha dicho, de los seguidores de otras religiones que, al igual que los cristianos, más allá de las formas externas que aún permanezcan en las prácticas del culto, por lo demás están totalmente homologados a las costumbres y al estilo de vida materialista y consumista propio de nuestra civilización. Así, una mujer musulmana que viste su ropa tradicional, como por ejemplo el velo, genera protestas y casi un sentimiento de repulsión que está en conformidad con nuestra “tradición”, los atuendos con los cuales se engalanan nuestras chicas respetando la última moda lanzada por la etiqueta del momento. Del mismo modo, la apertura de un kebab o de una carnicería musulmana irían a desfigurar, para los lugareños “identitarios”, la decoración urbana de nuestras calles, mientras que un McDonalds o un local de moda y tendencias no. Los ejemplos podrían multiplicarse: hace años, en Suiza, los partidos identitarios organizaron un referéndum contra la construcción de minaretes porque éstos implicarían la ruptura de la arquitectura típica de las ciudades suizas: no consta que tales partidos, en Suiza como en otros lugares, se hayan levantado alguna vez, al menos con el mismo ardor, en contra de la excéntrica arquitectura moderna que desfigura habitualmente nuestros centros históricos, como en general nuestros barrios, por no hablar de los eco-monstruos de nuestros suburbios, donde ahora todo el sentido de la proporción, la armonía, y por lo tanto de lo “bello” está completamente perdido, y no ciertamente por culpa de los minaretes o de quién sabe qué otro exótico edificio.

El Islam, en cambio, incluso en nuestras sociedades, a menudo trae elementos y valores realmente incompatibles con la modernidad y, por lo tanto, difícilmente “integrables”. Y es eso lo que las fuerzas identitarias le reprochan, viendo a sus miembros como sujetos extraños y alógenos respecto a nuestro mundo, a diferencia, como se ha dicho, de los seguidores de otras religiones que, al igual que los cristianos, más allá de las formas externas que aún permanezcan en las prácticas del culto, por lo demás están totalmente homologados a las costumbres y al estilo de vida materialista y consumista propio de nuestra civilización. Así, una mujer musulmana que viste su ropa tradicional, como por ejemplo el velo, genera protestas y casi un sentimiento de repulsión que está en conformidad con nuestra “tradición”, los atuendos con los cuales se engalanan nuestras chicas respetando la última moda lanzada por la etiqueta del momento. Del mismo modo, la apertura de un kebab o de una carnicería musulmana irían a desfigurar, para los lugareños “identitarios”, la decoración urbana de nuestras calles, mientras que un McDonalds o un local de moda y tendencias no. Los ejemplos podrían multiplicarse: hace años, en Suiza, los partidos identitarios organizaron un referéndum contra la construcción de minaretes porque éstos implicarían la ruptura de la arquitectura típica de las ciudades suizas: no consta que tales partidos, en Suiza como en otros lugares, se hayan levantado alguna vez, al menos con el mismo ardor, en contra de la excéntrica arquitectura moderna que desfigura habitualmente nuestros centros históricos, como en general nuestros barrios, por no hablar de los eco-monstruos de nuestros suburbios, donde ahora todo el sentido de la proporción, la armonía, y por lo tanto de lo “bello” está completamente perdido, y no ciertamente por culpa de los minaretes o de quién sabe qué otro exótico edificio.

Il passo che seguì allo smantellamento dell’esercito e della gloriosa marina da guerra, fu quindi la cosiddetta Dichiarazione di umanità di quel fatidico primo giorno di Gennaio. Hirohito stesso fu molto turbato dal fatto di dover negare la sua discendenza divina, così come era stato previsto nel documento in inglese che gli fu sottoposto; decise allora di apportare una significativa modifica, facendo apparire il passaggio come fosse una rinuncia volontaria al suo status di dio vivente in nome del supremo interesse del Giappone. Accanto alla Dichiarazione fu emanata la Direttiva sullo scintoismo che prevedeva l’abolizione dello scintoismo di Stato e la sua definitiva separazione giuridica dalle istituzioni: per i giapponesi riverire la nazione e l’imperatore non sarebbe più stato un dovere. In seguito furono in molti i giapponesi che criticarono Hirohito per il suo gesto, considerato un vero e proprio atto di tradimento verso tutti coloro che in lui avevano creduto e per cui avevano donato la propria vita. Fra questi spicca certamente quello Yukio Mishima che non riuscì mai ad accettare il cambiamento imposto alla società giapponese, arrivando al punto da compiere il rito del seppuku

Il passo che seguì allo smantellamento dell’esercito e della gloriosa marina da guerra, fu quindi la cosiddetta Dichiarazione di umanità di quel fatidico primo giorno di Gennaio. Hirohito stesso fu molto turbato dal fatto di dover negare la sua discendenza divina, così come era stato previsto nel documento in inglese che gli fu sottoposto; decise allora di apportare una significativa modifica, facendo apparire il passaggio come fosse una rinuncia volontaria al suo status di dio vivente in nome del supremo interesse del Giappone. Accanto alla Dichiarazione fu emanata la Direttiva sullo scintoismo che prevedeva l’abolizione dello scintoismo di Stato e la sua definitiva separazione giuridica dalle istituzioni: per i giapponesi riverire la nazione e l’imperatore non sarebbe più stato un dovere. In seguito furono in molti i giapponesi che criticarono Hirohito per il suo gesto, considerato un vero e proprio atto di tradimento verso tutti coloro che in lui avevano creduto e per cui avevano donato la propria vita. Fra questi spicca certamente quello Yukio Mishima che non riuscì mai ad accettare il cambiamento imposto alla società giapponese, arrivando al punto da compiere il rito del seppuku

Sa postérité est telle que ce que nous connaissons réellement de sa vie fraye avec le romanesque et le légendaire, et bien sûr ce personnage atypique a ses adulateurs et détracteurs chez les amoureux de la culture japonaise et des arts martiaux. Ce qui est certain, à la lecture des Écrits sur les Cinq Éléments, c'est que Musashi était un esprit libre en phase avec la vie. Ces cinq rouleaux rédigés à l'extrême fin de sa vie étaient destinés à transmettre l'essence de son art à ses élèves.

Sa postérité est telle que ce que nous connaissons réellement de sa vie fraye avec le romanesque et le légendaire, et bien sûr ce personnage atypique a ses adulateurs et détracteurs chez les amoureux de la culture japonaise et des arts martiaux. Ce qui est certain, à la lecture des Écrits sur les Cinq Éléments, c'est que Musashi était un esprit libre en phase avec la vie. Ces cinq rouleaux rédigés à l'extrême fin de sa vie étaient destinés à transmettre l'essence de son art à ses élèves.

Miyamoto Mikinosuke deviendra un vassal de la seigneurie de Himeji (1622), mais le jeune homme suivra son seigneur dans la mort en pratiquant le suicide rituel (1626). Miyamoto Iori, qui serait peut-être un sien neveu, entrera au service du seigneur Ogasawara (1626). Surtout, en 1624, il séjourne à Edo, la capitale, et noue d’étroites relations avec Hayashi Razan, un célèbre savant confucéen, ce dernier proche du Shôgun l’aurait proposé comme maître de sabre, mais le Shôgun disposant déjà de deux maîtres d’armes de renom, Yagyû Munenori (école shinkage ryû) et