Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com

Ex: http://www.counter-currents.com

Julius Evola

Metaphysics of War:

Battle, Victory, and Death in the World of Tradition

Aarhus, Denmark: Integral Tradition Publishing, 2007

Italian Traditionalist Julius Evola (1898–1974) needs little introduction to the readers of Counter-Currents. The Metaphysics of War is a collection of sixteen essays by Evola, published in various periodicals in the years 1935–1950.

These essays constitute what is certainly the most radical attempt ever made to justify war. This justification takes place essentially on two levels: one profane, the other sacred. At the profane (meaning simply “non-sacred”) level, Evola argues that war is one of the primary means by which heroism expresses itself, and he regards heroism as the noblest expression of the human spirit. Evola reminds us that war is a time in which both combatants and non-combatants realize that they may lose their lives and everything and everyone they value at any moment. This creates a unique moral opportunity for individuals to learn to detach themselves from material possessions, relationships, and concern for their own safety. War puts everything into perspective, and Evola states that it is in such times that “a greater number of persons are led towards an awakening, towards liberation” (p. 135):

From one day to the next, even from one hour to the next, as a result of a bombing raid one can lose one’s home and everything one most loved, everything to which one had become most attached, the objects of one’s deepest affections. Human existence becomes relative–it is a tragic and cruel feeling, but it can also be the principle of a catharsis and the means of bringing to light the only thing which can never be undermined and which can never be destroyed. [p. 136]

So far, these ideals may seem quite similar to those espoused by Ernst Jünger–and indeed Evola alludes to him in one place in the text (p. 153), and is uncharacteristically positive. (Usually when Evola references a modern author it is almost always to stick the knife in.) However, Evola goes well beyond Jünger, for he adds to this ideal of heroism and detachment a “spiritual” and even supernatural dimension (this is the “sacred” level I alluded to earlier). In essential terms, Evola argues that the heroism forged in war is a means to transcendence of this world of suffering and to identification with the source of all being. He even argues that the hero may attain a kind of magical quality.

Unsurprisingly, Evola attempts to situate his treatment of heroism in terms of the doctrine of the “four ages,” a staple of Traditionalist writings. The version of the four ages most familiar to Western readers is the one found in Ovid, where the ages are gold, silver, bronze, and iron. However, Evola has squarely in mind the Indian version wherein the iron age (the most degraded of all) is referred to as the Kali Yuga. To these correspond the four castes of traditional society, with a spiritual, priestly element dominating in the first age, the warrior in the second, the merchant (or, bourgeoisie, the term most frequently used by Evola) in the third, and the slave or servant in the fourth.

When the bourgeoisie dominates in the third age, “the concept of the nation materializes and democratizes itself”; “an anti-aristocratic and naturalistic conception of the homeland is formed” (p. 24). Ironically, when I read this I could not help but think of fascist Italy and National Socialist Germany. To the liberal mind, fascism and Nazism both are “ultra-conservative” (to put it mildly). From the Traditionalist perspective, however, both are modern, populist movements. And National Socialism especially found itself caught up in reductionist, biological theories of “the nation.” Nevertheless, Evola writes that “fascism appears to us as a reconstructive revolution, in that it affirms an aristocratic and spiritual concept of the nation, as against both socialist and internationalist collectivism, and the democratic and demagogic notion of the nation” (p. 27). In other words, whatever its shortcomings may be, fascism is for Evola a means to restore Tradition. Evola also writes approvingly of fascism having elevated the nation to the status of “warrior nation.” And he states that the next step “would be the spiritualization of the warrior principle itself” (p. 27). Of course, it seems to have been Heinrich Himmler’s ambition to turn his SS into an elite corps of “spiritual warriors.” One wonders if this was the reason Evola began courting members of the SS in the late 1930s (a matter briefly discussed in John Morgan’s introduction to this volume).

Evola tells us that the end of the reign of the bourgeoisie opens up two paths for Europe. One is a shift to the subhuman, and Evola makes it clear that this is what bolshevism represents. The fourth age is the age of the slave and of the triumph of slave morality in the form of communism. The other possibility, however, is a shift to the “superhuman.” As Evola has said elsewhere, the Kali Yuga may be an age of decline but it presents unique opportunities for self-transformation and the attainment of personal power. (“A radical destruction of the ‘bourgeois’ who exists in every man is possible in these disrupted times more than in any other,” p. 137). Those who “ride the tiger” are able not just to withstand the onslaught of negative forces in the fourth age, but actually to use them to rise to higher levels of self-realization. War is one such negative force, and Evola maintains that the idea of war as a path to spiritual transformation is a Traditional view.

According to Evola, the ancient Aryans held that there are two paths to enlightenment: contemplation and action. In traditional Indian terms, the former is the path of the brahmin and the latter of the kshatriya (the warrior caste). Both are forms of yoga, which literally means any practice that has as its aim connecting the individual to his true self, and to the source of all being (which are, in fact, the same thing). The yoga of action is referred to as karma yoga (where karma simply means “action”), and the primary text which teaches it is the Bhagavad-Gita. Evola returns again and again to the Bhagavad-Gita throughout The Metaphysics of War, and it really is the primary text to which Evola’s philosophy of “war as spiritual path” is indebted. The work forms part (a very small part, actually) of the epic poem Mahabharata, the story of which culminates in an apocalyptic war called Kurukshetra. On the eve of battle, the consummate warrior Arjuna (the Siegfried of the piece) surveys the two camps from afar and realizes that on his enemy’s side are many men who are his friends and relations. When Arjuna reflects on the fact that he will have to kill these men the following day, he falters. Fortunately, his charioteer–who is actually the god Krishna–is there to teach him the error of his ways. Krishna tells Arjuna that these men are already dead, for their deaths have been ordained by the gods. In killing them, Arjuna is simply doing his duty and playing his role as a warrior. He must set aside his personal feelings and concentrate on his duty; he must literally become a vehicle for the execution of the divine plan.

One might well ask, what’s in it for Arjuna? The answer is that this following of duty becomes a path by which he may triumph over his fears, his passions, his weaknesses–all those things that tie him to what is ephemeral. Following his duty becomes a way for Arjuna to rise above his lesser self and to connect with the divine. This is not mere piety or “love of God.” It is a way to tap into a superhuman source of power and wisdom. The result is that Arjuna becomes more than merely human.

In fact, Krishna puts Arjuna in a situation in which he must fight two wars. One, the “lesser” war is external–it is the one fought on the battlefield with swords and spears. The other, “greater” war is internal and is fought against the internal enemy: “passion, the animal thirst for life” (p. 52). Evola places a great deal of emphasis on this distinction. What Krishna really teaches Arjuna is that in order to fight the lesser war, he must fight the greater one. Really, unless one is able to conquer one’s weaknesses, nothing else may be accomplished. This opens up the possibility that there may be “warriors” who never fight in any conventional, “external” wars. These would be warriors of the spirit. Evola believes that one can be a true warrior without ever lifting a sword or a gun, by conquering the enemy within oneself. And he mentions initiatic cults, like Mithraism, which conceived of their members on the model of soldiers.

Nevertheless, the focus in The Metaphysics of War is really on actual, physical combat as a means to spiritual transformation. Evola tells us that the warrior ceases to act as an ordinary person, and that a non-human force transfigures his action. The warrior who does not fear death becomes death itself. This is one of the major lessons imparted by Krishna in the Bhagavad-Gita. It is not just a matter of “waking up” or becoming tougher and harder (as it is in Jünger). Evola clearly suggests that there is a supernatural element involved, though his remarks are far from clear. He writes that “the one who experiences heroism spiritually is pervaded with a metaphysical tension, an impetus, whose object is ‘infinite,’ and which, therefore, will carry him perpetually forward, beyond the capacity of one who fights from necessity, fights as a trade, or is spurred by natural instincts or external suggestion” (p. 41). Elsewhere Evola states that when the “right intention” is present “then one has given birth to a force which will not be able to miss the supreme goal” (p. 48). Heroic experiences seem “to possess an almost magical effectiveness: they are inner triumphs which can determine even material victory and are a sort of evocation of divine forces intimately tied to ‘tradition’ and ‘the race of the spirit’ of a given stock” (p. 81).

The suggestion here is that the experience of combat, fought with the right intention, results in a kind of ecstasy (an “active ecstasy” as Evola says on p. 80). The Greek ekstasis literally means “standing outside onself.” In combat one is lifted out of one’s ordinary self and, more specifically, out of one’s concern with the mundane cares of life. One enters into a state where one ceases even to care about personal survival. It is at this point that one has ceased to identify with the “animal” elements in the human personality and has tapped into that part of us that seems to be a divine spark. This is not, however, an intellectual state or “realization.” Instead, it is a new state of being, which pervades the entire person. The ancient Germans called it wut and odhr. And from these two words derive two of the names of the chief Germanic god: Wuotan and Odin. Odin is not, however, conceived simply as the god of war; he is also the god of wisdom and spiritual transformation. In this state of ecstasy, one feels oneself lifted above the merely human; one’s senses and reflexes become more acute, one’s movements more graceful, life suddenly comes into perspective and is seen as the transient affair that it really is, and one feels invincible, capable of accomplishing anything. (A dim simulacrum of this is experienced in athletic competition.) One has, in fact, become a god.

Evola ties this achievement of self-transformation through combat into a “general vision of life,” which he expresses in one of the most memorable metaphysical passages in this small volume:

[L]ike electrical bulbs too brightly lit, like circuits invested with too high a potential, human beings fall and die only because a power burns within them which transcends their finitude, which goes beyond everything they can do and want. This is why they develop, reach a peak, and then, as if overwhelmed by the wave which up to a given point had carried them forward, sink, dissolve, die and return to the unmanifest. But the one who does not fear death, the one who is able, so to speak, to assume the powers of death by becoming everything which it destroys, overwhelms and shatters–this one finally passes beyond limitation, he continues to remain upon the crest of the wave, he does not fall, and what is beyond life manifests itself within him. [p. 54]

Throughout The Metaphysics of War, Evola describes the various virtues of the warrior. These are the characteristics one must have to be effective in battle, and receptive to the sort of experience Evola describes. Again, however, it is very clear that he believes that all those who follow a path of spiritual transformation are warriors. Evola describes the warrior as without any doubt or hesitation; as having a bearing that suggests he “comes from afar”; as holding a world-affirming outlook. The warrior takes pleasure in danger and in being put to the test. (The lesson here for all of us, Evola says, is to find the meaning in adversity, and to take hardships as calls upon our nobility.) The warrior regards as comrades only those he can respect; he has a passion for distance and order; he has the ability to subordinate his passions to principles. The warrior’s relations with others are direct, clear, and loyal. He carries himself with a dignity devoid of vanity, and loathes the trivial.

Above all, however, Evola emphasizes the importance of detachment:

detachment towards oneself, towards things and towards persons, which should instill a calm, an incomparable certainty and even, as we have before stated, an indomitability. It is like simplifying oneself, divesting oneself in a state of waiting, with a firm, whole mind, with an awareness of something that exists beyond all existence. From this state the capacity will also be found of always being able to commence, as if ex nihilo, with a new and fresh mind, forgetting what has been and what has been lost, focusing only on what positively and creatively can still be done. [p. 137]

Evola offers us a vision of life as a member in a spiritual army. The standard, liberal view of the military is in effect that it is a necessary evil, and that the military and its values are not a suitable model for individual lives or societies. Evola argues instead that true civilization is conceived in heroic and “virile” terms. Readers of Evola’s other works will be familiar with his concept of “spiritual virility.” Mere physical virility is the element in the man that he shares with other male animals. But this is not true or absolute manhood. True manhood is achieved in the spirit, in developing the sort of hardness, detachment, and perspective on life that is characteristic of the warrior. Rene Guenon (a major influence on Evola) called the modern age “the reign of quantity.” It is typical of our time that we have come to see manhood entirely in terms of quantities of various kinds: how many pounds one can bench press or squat; numbers of sexual partners; inches of height; inches of penis; the number of zeros in one’s bank balance; the number of cylinders in one’s engine, etc. Just as in Huxley’s Brave New World, our masters have striven to create a society without conflict; a “nice” and “tolerant” society. And women have invaded virtually every arena of competition that used to be exclusively male, and ruined them for everyone. Under such circumstances, how is spiritual virility to develop? It is no surprise that our conception of virility is a purely physical and quantitative one. Evola evidently saw in fascism a means to awaken spiritual virility in the Italian male. He says that the starting point for fascist ethics is “scorn for the easy life” (p. 62).

Unlike other thinkers on the right, Evola never was particularly interested in biological conceptions of race, because he believed that human nature as such was irreducible to biology. He opposed reductionism, in short, and believed in a spiritual (i.e., non-material) component to our identity. Evola articulates his views on race in much greater detail elsewhere. Here he reminds us of his belief in a “super race” of the spirit: a race of men who are like-souled, and not necessarily like-bodied. Nevertheless, Evola realized the connection between the body and the spirit. He did not believe that all the (biological) races are equally fitted for achieving heroism. What Evola was most concerned to combat was a racialism that reduced heroism or mastery to simple membership in a race defined by certain biological characteristics. For Evola, heroism is really achieved in a step beyond the biological, and in mastery over it.

One will also find little in Evola that celebrates “the nation.” Evola’s ideal of heroism transcends national identity. This comes out most clearly in his discussion of the Crusades: “In fact, the man of the Crusades was able to rise, to fight and to die for a purpose which, in its essence, was supra-political and supra-human, and to serve on a front defined no longer by what is particularistic, but rather by what is universal” (p. 40, italics in original). Having written this, however, Evola immediately realized that the powers that be might see this (correctly) as implying that it is the achievement of heroism as such that is important, not merely the achievement of heroism in service to one’s people. A further implication of this, of course, is that the hero is raised above his people. And so Evola writes in the next paragraph, “Naturally this must not be misunderstood to mean that the transcendent motive may be used as an excuse for the warrior to become indifferent, to forget the duties inherent in his belonging to a race and to a fatherland” (pp. 40-41). Evola is not really being disingenuous here. Taking a cue again from the Bhagavad-Gita, one can say that it is the performance of one’s duty to race and fatherland that is the path to liberation. But as the wise man once said, when the raft takes us to the other shore, we do not put it on our backs and carry on with it. As Rajayoga teaches, there is no god (and certainly no country) above an awakened man. Evola is a fundamentally a philosopher of the left hand path, not a conservative. This individualistic element in him is troublesome for many on the right, and it is one of the primary reasons why he was unable to wholly reconcile himself to fascism.

Nine of these essays were written during the Second World War, and it is interesting to see how Evola situates his understanding of the conflict within his philosophy. In one essay written on the eve of the war, Evola states that “If the next war is a ‘total war’ it will mean also a ‘total test’ of the surviving racial forces of the modern world. Without doubt, some will collapse, whereas others will awaken and arise. Nameless catastrophes could even be the hard but necessary price of heroic peaks and new liberations of primordial forces dulled through grey centuries. But such is the fatal condition for the creation of any new world–and it is a new world that we seek for the future” (p. 68). It is doubtful that the war’s outcome either surprised or demoralized Evola. As noted earlier, he believed strongly in a cyclical view of history, and saw our age as a period of inevitable decline. It could not have surprised him that the combined forces of bourgeois and Bolshevik prevailed. In the final essay of in this volume, published five years after the end of the war, Evola reflects that “what is really required to defend ‘the West’” against the forces of barbarism “is the strengthening, to an extent perhaps still unknown to Western man, of a heroic vision of life” (p. 152).

Evola makes it clear that his position is not an unqualifiedly pessimistic one. The Kali Yuga is not the final age; history is cyclical, and a new and better age will follow this one. In each period, the stage is set for the next. The actions of those who resist this age set the stage for what is to come. Hence, though speaking and acting on behalf of truth may seem futile given the degradation that surrounds us, ultimately our resistance is part of the mechanism of the great cosmic wheel which will, in time, swing things back to truth and to Tradition. In the act of resisting, heroism is born in us and instantly we become creatures who no longer belong to this age, who “come from afar.” We become beacons pointing the way to the future, and simultaneously back to a glorious past. Evola writes that “a teaching peculiar to the ancient Indo-Germanic traditions was that precisely those who, in the dark age, in spite of all, resist, will be able to obtain fruits which those who lived in more favorable, less hard periods could seldom reach” (p. 61).

The Metaphysics of War is required reading for all those interested in the Traditionalist movement. But it will be of special appeal to a certain sort of man, who scorns the easy life and seeks to give birth to something noble and heroic in himself.

Note: The Metaphysics of War is available for purchase here.

Gnose et politique. Apparamment deux do- maines sans rapports aucuns l'un avec l'autre. La Gnose, c'est la théologie, la religion de la fuite hors des vanités de ce bas monde. La Gnose, c'est le refus de l'histoire, donc l'exact opposé du politique qui, lui, est immersion totale dans l'imma- nence de la Cité, dans le grouillement des passions et des intérêts. Pour Jacob TAUBES, pourtant, il est possible d'interpré- ter historiquement le déploiement des idéaux gnostiques, de repérer les traces que le mental gnostique a laissé, par le truchement du christianisme, dans les idéologies politiques. Ce travail de recherche, il l'a entrepris lors d'un colloque de la Werner-Reimers-Stiftung, tenu à Bad Homburg en septembre 1982. Les actes de ce colloque sont désormais disponibles sous forme de livre (références infra).

Gnose et politique. Apparamment deux do- maines sans rapports aucuns l'un avec l'autre. La Gnose, c'est la théologie, la religion de la fuite hors des vanités de ce bas monde. La Gnose, c'est le refus de l'histoire, donc l'exact opposé du politique qui, lui, est immersion totale dans l'imma- nence de la Cité, dans le grouillement des passions et des intérêts. Pour Jacob TAUBES, pourtant, il est possible d'interpré- ter historiquement le déploiement des idéaux gnostiques, de repérer les traces que le mental gnostique a laissé, par le truchement du christianisme, dans les idéologies politiques. Ce travail de recherche, il l'a entrepris lors d'un colloque de la Werner-Reimers-Stiftung, tenu à Bad Homburg en septembre 1982. Les actes de ce colloque sont désormais disponibles sous forme de livre (références infra).

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Le Sénat de Californie vient d’entériner une proposition de loi spéciale formulée par le député Bob Blumenfield (photo), élu du Parti Démocrate. Le 1 janvier 2011, des conditions particulières pourront être imposées, dont l’objectif est de demander d’énormes compensations, sous prétexte que les chemins de fer français ont joué un certain rôle pendant la seconde guerre mondiale. Blumenfield et ses alliés visent essentiellement la déportation des juifs entre 1942 et 1944. Ils reprochent à la SNCF d’avoir participé au transport de déportés en direction des camps de concentration. L’entreprise d’Etat française refuse depuis des années d’accepter toute forme de responsabilité en cette affaire. Blumenfield rétorque : « Maintenant, on voit arriver cette entreprise en Californie en voulant prendre une part de la plus grande commande publique de l’histoire de notre Etat. Je pense que si une entreprise veut obtenir l’argent du contribuable, elle doit assumer la responsabilité de ses actes dans le passé ». La SNCF doit dès lors payer un dédommagement aux survivants des camps de concentration.

Le Sénat de Californie vient d’entériner une proposition de loi spéciale formulée par le député Bob Blumenfield (photo), élu du Parti Démocrate. Le 1 janvier 2011, des conditions particulières pourront être imposées, dont l’objectif est de demander d’énormes compensations, sous prétexte que les chemins de fer français ont joué un certain rôle pendant la seconde guerre mondiale. Blumenfield et ses alliés visent essentiellement la déportation des juifs entre 1942 et 1944. Ils reprochent à la SNCF d’avoir participé au transport de déportés en direction des camps de concentration. L’entreprise d’Etat française refuse depuis des années d’accepter toute forme de responsabilité en cette affaire. Blumenfield rétorque : « Maintenant, on voit arriver cette entreprise en Californie en voulant prendre une part de la plus grande commande publique de l’histoire de notre Etat. Je pense que si une entreprise veut obtenir l’argent du contribuable, elle doit assumer la responsabilité de ses actes dans le passé ». La SNCF doit dès lors payer un dédommagement aux survivants des camps de concentration.

C’est une fin de non recevoir claire et nette que le tribunal constitutionnel colombien a adressé aux Etats-Unis. L’objet de cette décision était un accord militaire contesté, qui aurait permis à l’armée américaine d’utiliser sept bases militaires sur territoire colombien. Le tribunal suprême de ce pays latino-américain vient de décider que le traité signé à la fin de l’année dernière entre Bogota et Washington doit être déclaré nul et non avenu.

C’est une fin de non recevoir claire et nette que le tribunal constitutionnel colombien a adressé aux Etats-Unis. L’objet de cette décision était un accord militaire contesté, qui aurait permis à l’armée américaine d’utiliser sept bases militaires sur territoire colombien. Le tribunal suprême de ce pays latino-américain vient de décider que le traité signé à la fin de l’année dernière entre Bogota et Washington doit être déclaré nul et non avenu.

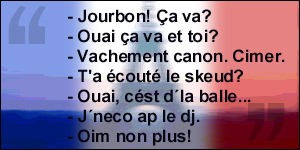

La comparaison de ces petites notes laisse apparaître des constantes dans l'écriture: l'orthographe est respectée (d'où, il est plus correct d'écrire verlen), sont supprimées les lettres muettes en fin de mot, les doubles consonnes lorsqu'elles se retrouvent en début, les apostrophes sont bannies et le mot élidé est soudé au mot suivant; le S et le ILLE entraîne des modifications selon la phonétique (baiser = zébai, baisser = sébai); le verlan distingue les terminaisons avec consonnes prononcée et celles avec E muet (travail = vailtra, travaille = yevatra); aucune abréviation n'est notée et les diphtongues sont coupées en deux sons le plus souvent (viens = invi); les mots d'une syllabe sont laissés tels quels.

La comparaison de ces petites notes laisse apparaître des constantes dans l'écriture: l'orthographe est respectée (d'où, il est plus correct d'écrire verlen), sont supprimées les lettres muettes en fin de mot, les doubles consonnes lorsqu'elles se retrouvent en début, les apostrophes sont bannies et le mot élidé est soudé au mot suivant; le S et le ILLE entraîne des modifications selon la phonétique (baiser = zébai, baisser = sébai); le verlan distingue les terminaisons avec consonnes prononcée et celles avec E muet (travail = vailtra, travaille = yevatra); aucune abréviation n'est notée et les diphtongues sont coupées en deux sons le plus souvent (viens = invi); les mots d'une syllabe sont laissés tels quels.

zusetzen. Seitdem ist nach Angaben der US-Gesundheitsbehörde CDC die Häufigkeit von Fettleibigkeit in den USA sprunghaft gestiegen. Waren 1970 nur etwa 15 Prozent der Amerikaner fettleibig, so seien es laut CDC heute fast ein Drittel. Stark fruktosehaltiger Maissirup (HFCS) findet sich in den USA heute überall in Lebensmitteln und Getränken, auch als Zusatzstoff in Pizzas, gebackenen Bohnen, Bonbons, Hefebroten, gesüßtem Joghurt, Babynahrung, Ketchup, Mayonnaise, Plätzchen, Bier, Limonaden, Säften und Fertiggerichten. Im Durchschnitt konsumiert jeder Amerikaner 60 Pfund fruktosehaltige Süßungsmittel pro Jahr.

zusetzen. Seitdem ist nach Angaben der US-Gesundheitsbehörde CDC die Häufigkeit von Fettleibigkeit in den USA sprunghaft gestiegen. Waren 1970 nur etwa 15 Prozent der Amerikaner fettleibig, so seien es laut CDC heute fast ein Drittel. Stark fruktosehaltiger Maissirup (HFCS) findet sich in den USA heute überall in Lebensmitteln und Getränken, auch als Zusatzstoff in Pizzas, gebackenen Bohnen, Bonbons, Hefebroten, gesüßtem Joghurt, Babynahrung, Ketchup, Mayonnaise, Plätzchen, Bier, Limonaden, Säften und Fertiggerichten. Im Durchschnitt konsumiert jeder Amerikaner 60 Pfund fruktosehaltige Süßungsmittel pro Jahr.

«C'est avec stupéfaction que j'ai appris le décès de notre ami Jean Varenne. J'avais connu Jean Varenne au cours de sa dernière année d'enseignement à l'Université de Lyon III en 1986-87, alors que je préparais ma licence d'histoire. Pour moi, Jean Varenne était plus qu'un simple professeur, c'était aussi le Président du GRECE et le directeur de la revue éléments, organe d'un milieu que j'apprenais à connaître à l'époque. Chose étrange pour un si grand savant

«C'est avec stupéfaction que j'ai appris le décès de notre ami Jean Varenne. J'avais connu Jean Varenne au cours de sa dernière année d'enseignement à l'Université de Lyon III en 1986-87, alors que je préparais ma licence d'histoire. Pour moi, Jean Varenne était plus qu'un simple professeur, c'était aussi le Président du GRECE et le directeur de la revue éléments, organe d'un milieu que j'apprenais à connaître à l'époque. Chose étrange pour un si grand savant

.jpg)

.jpg) zurück schrieb Callonge: »Ich will ins Haus zurück, nicht immer nur erzwungenermaßen, sondern öfter, länger, freiwilliger. Ich will nicht meine Kinder nur zwei Stunden täglich sehen. Ich weigere mich zu wählen zwischen Beruf und Familie. Ich will beides. Ich will leben!« Dieses Buch hatte in Frankreich der Diskussion um die Befreiung der Frau bereits vor dreißig Jahren entscheidende neue Impulse gegeben.

zurück schrieb Callonge: »Ich will ins Haus zurück, nicht immer nur erzwungenermaßen, sondern öfter, länger, freiwilliger. Ich will nicht meine Kinder nur zwei Stunden täglich sehen. Ich weigere mich zu wählen zwischen Beruf und Familie. Ich will beides. Ich will leben!« Dieses Buch hatte in Frankreich der Diskussion um die Befreiung der Frau bereits vor dreißig Jahren entscheidende neue Impulse gegeben..jpg) wie DER SPIEGEL, DIE WELT oder die Süddeutsche Zeitung die Feministin Badinter derzeit ebenso emphatisch hochjubeln wie ihre deutschen Mitstreiterinnen Dorn oder Schwarzer –

wie DER SPIEGEL, DIE WELT oder die Süddeutsche Zeitung die Feministin Badinter derzeit ebenso emphatisch hochjubeln wie ihre deutschen Mitstreiterinnen Dorn oder Schwarzer –

Es ist Elisabeth Badinter, seit Jahrzehnten Frankreichs (liberale!) Vorzeigefeministin, die ihr Land derzeit von einem massiven roll back in punkto Emanzipation bedroht sieht. Ihr Buch Le conflit. La femme et la mère, das in Frankreich gleich nach Erscheinen auf Platz 1 der Verkaufslisten schnellte und heiß diskutiert wurde, ist ein Plädoyer für die Abtrennung der mütterlichen Sphäre von der weiblichen Identität.

Es ist Elisabeth Badinter, seit Jahrzehnten Frankreichs (liberale!) Vorzeigefeministin, die ihr Land derzeit von einem massiven roll back in punkto Emanzipation bedroht sieht. Ihr Buch Le conflit. La femme et la mère, das in Frankreich gleich nach Erscheinen auf Platz 1 der Verkaufslisten schnellte und heiß diskutiert wurde, ist ein Plädoyer für die Abtrennung der mütterlichen Sphäre von der weiblichen Identität. Cher Robert Steuckers,

Cher Robert Steuckers,