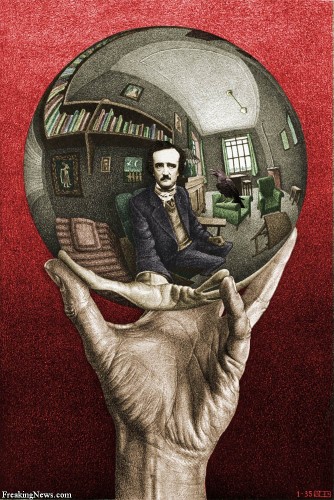

Edgar Allan Poe nasce a Boston nel 1809 e muore a Baltimora nel 1849. La sua breve e infelice esistenza è stata caratterizzata da tre successivi, laceranti distacchi da altrettante figure femminili per lui altamente significative: la madre, morta quand’egli aveva appena tre anni (il padre li aveva entrambi abbandonati), per cui fu accolto in casa dai coniugi Allan; la signora Francesc Allan, quand’egli ne aveva venti, e che non poté neanche giungere in tempo per salutare l’ultima volta prima delle esequie; e la moglie-bambina, quella Virginia Clemm (sposata appena tredicenne), che era sua cugina prima – in quanto figlia della zia paterna Maria Clemm – e che morirà, dopo una lunga agonia, consumata dalla tubercolosi. Come scrittore si è cimentato in molti ambiti della letteratura. In quello della teoria e della critica letteraria ha scritto Fondamento del verso, 1843; La filosofia della composizione, 1846; Marginalia ed Eureka, 1849; Il principio poetico, pubblicato postumo, nel 1850. Tutte queste opere sono state studiate e tradotte in Europa, specialmente da Charles Baudelaire; in esse Poe prende posizione contro la concezione romantica della spontaneità dell’arte (sintetizzata dal pittore tedesco Caspar David Friedrich nella formula: “L’unica vera sporgente dell’arte è il nostro cuore”) e a favore di una concezione secondo la quale l’opera letteraria può essere creata come un sapiente meccanismo, montata e smontata pezzo a pezzo.

Edgar Allan Poe nasce a Boston nel 1809 e muore a Baltimora nel 1849. La sua breve e infelice esistenza è stata caratterizzata da tre successivi, laceranti distacchi da altrettante figure femminili per lui altamente significative: la madre, morta quand’egli aveva appena tre anni (il padre li aveva entrambi abbandonati), per cui fu accolto in casa dai coniugi Allan; la signora Francesc Allan, quand’egli ne aveva venti, e che non poté neanche giungere in tempo per salutare l’ultima volta prima delle esequie; e la moglie-bambina, quella Virginia Clemm (sposata appena tredicenne), che era sua cugina prima – in quanto figlia della zia paterna Maria Clemm – e che morirà, dopo una lunga agonia, consumata dalla tubercolosi. Come scrittore si è cimentato in molti ambiti della letteratura. In quello della teoria e della critica letteraria ha scritto Fondamento del verso, 1843; La filosofia della composizione, 1846; Marginalia ed Eureka, 1849; Il principio poetico, pubblicato postumo, nel 1850. Tutte queste opere sono state studiate e tradotte in Europa, specialmente da Charles Baudelaire; in esse Poe prende posizione contro la concezione romantica della spontaneità dell’arte (sintetizzata dal pittore tedesco Caspar David Friedrich nella formula: “L’unica vera sporgente dell’arte è il nostro cuore”) e a favore di una concezione secondo la quale l’opera letteraria può essere creata come un sapiente meccanismo, montata e smontata pezzo a pezzo.

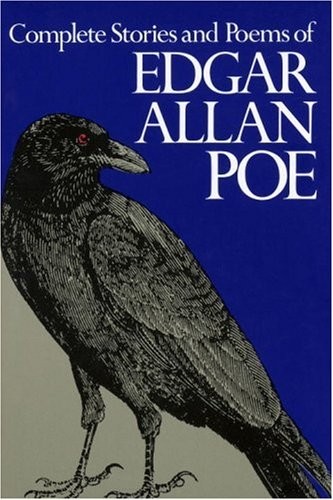

Pertanto se egli si situa, per motivi cronologici, nel contesto del romanticismo, la sua poetica nondimeno si colloca piuttosto alle sorgenti del simbolismo e precorre la grande stagione decandetistica, su su fino a Borges e a quegli scrittori che tendono a vedere nella scrittura un ambito totalmente autonomo, che vive di leggi proprie, separate dalla vita quotidiana. Nella poesia si è cimentato con la raccolta giovanile Tamerlano e altre poesie, del 1827; poi con Al Aaraaf, del 1829; con Poesie del 1831; e infine con Il corvo e altre poesie, del 1845: quest’ultima è stata la sua definitiva rivelazione e gli ha procurato (a soli quattro anni dalla morte) una certa, tardiva celebrità.

Ne Il Corvo (The Raven) il poeta, immerso nello studio ove cerca di soffocoare il dolore per la perdita della donna amata, ode un fruscìo a tarda notte: apre la porta, ma non c’è nessuno; poi sente ripetersi il rumore alla finestra: la apre, e un corvo entra e si posa su un busto di Minerva, fissandolo con occhi scontillanti e quasi demoniaci. Il poeta lo interroga per dare sollievo alla propria pena, e gli chiede se riuscirà mai ad attenuare il dolore che lo trafigge, ma sempre l’uccello risponde:

“Mai più” (“Nevermore”). […]

“‘O profeta, figlio del maligno – dissi – uccello

o demone, che ti mandi il Tentatore o ti porti la tempesta,

solitario eppure indomito sopra questa desolata

incantata terra, in questa casa orrida,

ti supplico,

di’: c’è un balsamo in Galaad? Dillo, avanti, te ne supplico!’

Ed il Corvo qui: ‘Mai più!’

‘O profeta – dissi – figlio del maligno, uccello

o demone,

per il Cielo sopra noi, per il Dio di tutti e due,

di’ a quest’anima angosciata se nel Paradiso mai

rivedrà quella fanciulla che Lenore chiamano

gli angeli,

la fanciulla pura e splendida che Lenore

chiamano gli angeli!’

Ed il Corvo qui: ‘Mai più!’.

‘E sia questa tua sentenza un addio fra noi’ alzandomi

gridai ‘torna alle plutonie rive oscure e alle tempeste!

Non lasciar neanche una piuma a ricordo de tuo inganno!

Voglio stare in solitudine, lascia il busto

sulla porta!’

Disse il Corvo qui: ‘Mai più!’

Ma quel corvo non volò, ed ancora, ancora posa

sopra il busto di Minerva, sulla porta

della stanza,

ed ha gli occhi come quelli di un diavolo

che sogna,

e la luce ne proietta l’ombra sopra il pavimento.

la mia anima dall’ombra mossa sopra il

pavimento

Non si leverà – mai più! [Trad. di A. Quattrone].

Anche per la “scoperta” della poesia di Poe è stata determinante la mediazione della cultura europea, e di quella francese in modo particolare: tradotto da Mallarmé, egli è giunto nel “salotto buono” della cultura americana solo molto più tardi, dopo la prematura scomparsa. Per quasi tutta la sua vita egli era stato uno spostato, un emarginato, un giullare, ignorato dai critici letterari imbevuti di puritanesimo e di “sano” pragmatismo; eppure aveva saputo interpretare più di chiunque altro gli incubi e le nevrosi dei suoi compatrioti, proprio in quanto essi li avevano negati o rimossi. La “scoperta” di Poe da parte degli Europei, d’altronde, non significa affatto – come pure è stato detto – che Poe sia il più “europeo” degli scrittori americani: anzi, è americanissimo (e in Europa, in Scozia per la precisione, non visse che pochi anni, da bambino, al seguito degli Allan, però in collegio); ma, per una serie di ragioni storico-culturali, la letteratura europea era più matura per riceverne e comprenderne il messaggio. Poe, inoltre, è stato un giornalista molto dotato; ha collaborato con giornali e riviste quali il Courier, il Southern Literary Messanger di Richmond, il Gift ed il Graham’s Magazine: portando quest’ultimo, tanto per fare un esempio delle sue eccezionali capacità, da una tiratura di 5.000 copie ad una di

40.000, dunque otto volte superiore.

Si è poi cimentato nel romanzo e nel racconto, ed è questo l’ambito dove ha lasciato l’orma più durevole, tanto che nessuno scrittore del terrore, dopo di lui – né americano, né europeo – ha potuto evitare di fare i conti con lui, di prendere posizione rispetto alla sua figura gigantesca. Come romanziere ha scritto Le avventure di Arthur Gordon Pym, pubblicato nel 1838: resoconto di una navigazione antartica permeato d’inquietudine, di orrore e di mistero, che risente del clima di entuasiamo per le prime scoperte antartiche da parte di Russi, Britannici, Francesi e Statunitensi. Il romanzo rimane volutamente interrotto e ha stuzzicato a tal punto la fantasia delle generazioni successive, che Jules Verne volle scriverne il seguito con La sfinge dei ghiacci. Verso la fine dell’opera, infatti, il protagonista e un suo compagno d’avventura, che una inspiegabile corrente marina calda ha portato oltre la barriera dei ghiacci gallegganti, verso le acque libere del Polo Sud, intravvedono, in mezzo al volo d’innumerevoli uccelli bianchi, una gigantesca figura umana che si leva all’orizzonte, d’un candore innaturale, e si staglia torreggiante su di loro.

“5 marzo. – Il vento era completamente cessato, ma noi continuavamo a correre lo stesso verso il sud, trascinati da una corrente irresistibile. Sarebbe stato naturale che provassimo dell’apprensione per la piega che prendevano le cose, invece niente. […]

“6 marzo.- Il vapore si era alzato di parecchi gradi e andava a poco a poco perdendo la sua tinta grigiastra. L’acqua era calda più che mai, e ancora più lattiginosa di prima. Ci fu una violenta agitazione del mare proprio vicinissimo a noi, accompagnata, come al solito, da uno strano balenio del vapore e da una momentana frattura lungo la base di esso. […]

“9 marzo. – La strana sostanza come di cenere continuava a pioverci attorno. La barriera di vapore era salita sull’orizzonte sud a un’altezza prodigiosa, e cominciava ad assumere una forma distinta. Io non sapevo paragonarla altro che a una immane cateratta la quale precipitasse silenziosamente in mare dall’alto di qualche favolosa montagna perduta nel cielo. La gigantesca cortina occupava l’orizzonte in tutta la sua estensione. Da essa non veniva alcun rumore.

“21 marzo. – Una funebre oscurità aleggiava su di noi ma dai lattiginosi recessi dell’oceano scaturiva un fulgore che si riverberava sui fianchi del battello. Eravamo quasi soffocati dal tempestare della cenere bianca che si accumulava su di noi e riempiva l’imbarcazione, mentre nell’acqua si scioglieva. La sommità della cateratta si perdeva nella oscurità della distanza. Nel frattempo risultava evidente che correvamo diritto su di essa ad una impressionante velocità. A tratti, su quella cortina sterminata, si aprivano larghe fenditure, che però subito si richiudevano, attraverso le quali, dal caos di indistinte forme vaganti che si agitavano al d ilà, scaturivano possenti ma silenziose correnti d’aria che sconvolgevano, nel loro turbine, l’oceano infiammato.

“22 marzo. – L’oscurità si era fatta più intensa e solo il luminoso riflettersi delle acque della bianca cortina tesa dinanzi a noi la rischiarava ormai. Una moltitudine di uccelli giganteschi, di un livido color bianco, si alzava a volo incessantemente dietro a noi per battere, appena ci vedevano, in ritirata gridando il sempiterno Tekeli-li. Nu-Nu [un indigeno della misteriosa isola di Tsalal che i due avevano fatto prigioniero] ebbe, a quelle grida un movimento sul fondo del battello, e, come noi lo toccammo, scoprimmo che aveva reso l’ultimo respiro. Fu allora che la nostra imbarcazione si precipitò nella morsa della cateratta dove si era spalancato un abisso per riceverci. Ma ecco sorgere sul nostro cammino una figura umana dal volto velato, di proporzioni assai più grandi che ogni altro abitatore della terra. E il colore della sua pelle era il bianco perfetto della neve.” [trad. di Elio Vittorini].

Dicevamo della lucidità, della “scientificità”della poetica del Nostro: ebbene, coloro che si son presi la briga di riportare sulla carta geografica la rotta della nave di Gordon Pym attraverso gli oceani, hanno avuto una sorpresa: congiungendone i punti, appariva nettamente la sagoma di un grande uccello con le ali spiegate – come i misteriosi uccelli bianchi che gridano il loro incessante Tekeli-li. Un caso, una semplice coincidenza? Ma Poe amava moltissimo i giochi di decrittazione, gli enigmi logici e linguistici: sempre nel Gordon Pym, il protagonista scopre, incisi sulla roccia dell’isola sconosciuta, dei caratteri apparentemente senza significato, ma che si riveleranno poi parole di antico egiziano, di etiopico, di arabo le quali accennano al segreto inaudito che si annida nella regione del Polo antartico. E tale passione per le sciarade, per i rompicapi, per l’applicazione pratica di una logica rigorosa di tipo matematico si rivela pienamente nel filone dei racconti polizieschi, particolarmente ne I delitti della rue Morgue, ne Lo scarabeo d’oro, ne La lettera rubata. Ricordi, forse, degli studi fatti a West Point, all’epoca del breve e fallimentate tentativo di farsi una carriera nell’esercito.

Dicevamo della lucidità, della “scientificità”della poetica del Nostro: ebbene, coloro che si son presi la briga di riportare sulla carta geografica la rotta della nave di Gordon Pym attraverso gli oceani, hanno avuto una sorpresa: congiungendone i punti, appariva nettamente la sagoma di un grande uccello con le ali spiegate – come i misteriosi uccelli bianchi che gridano il loro incessante Tekeli-li. Un caso, una semplice coincidenza? Ma Poe amava moltissimo i giochi di decrittazione, gli enigmi logici e linguistici: sempre nel Gordon Pym, il protagonista scopre, incisi sulla roccia dell’isola sconosciuta, dei caratteri apparentemente senza significato, ma che si riveleranno poi parole di antico egiziano, di etiopico, di arabo le quali accennano al segreto inaudito che si annida nella regione del Polo antartico. E tale passione per le sciarade, per i rompicapi, per l’applicazione pratica di una logica rigorosa di tipo matematico si rivela pienamente nel filone dei racconti polizieschi, particolarmente ne I delitti della rue Morgue, ne Lo scarabeo d’oro, ne La lettera rubata. Ricordi, forse, degli studi fatti a West Point, all’epoca del breve e fallimentate tentativo di farsi una carriera nell’esercito.

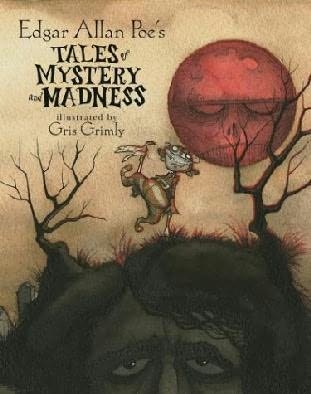

Ma i racconti ai quali è principalmente legata la fama di Poe sono, senza dubbio, quelli del mistero e del terrore: particolarmente alla raccolta Racconti del grottesco e dell’arabesco, del 1840. Solo una parte di essi si serve dell’elemento soprannaturale; tutti, però, nascono da un profondo sentimento di inquietudine, analizzato con freddo e lucido distacco, anche nelle situazioni più drammatiche e disperate. L’inquietudine, intendiamoci, può essere essenzialmente di due generi: quella metafisica e quella storica. L’inquietudine metafisica è strutturalmente legata alla condizione ontologica dell’uomo: creatura finita che anela all’infinito; come dice Sant’Agostino nelle Confessiones: “Inquietum est cor meum, donec requiescat in Te, Domine” (“inquieto è il mio cuore, finché non trova pace e riposo in Te, mio Dio”). E l’arte, per usare la terminologia del filosofo spiritualista Luigi Stefanini, è la “Parola Assoluta” che la persona finita pronunzia nel mondo dei sensibili, una parola carica di nostalgia verso la Persona Infinita dalla quale trae origine. Al contrario, l’inquietudine storica è frutto di condizioni particolari dello spazio-tempo di una determinata società; esprime l’angoscia dei momenti drammatici di trapasso dai “vecchi” valori ai “nuovi”: gli uni orma tramontati, gli altri non ancora ben delineati all’orizzonte. Una tipica età di trapasso, ad esempio, è stata quella della tarda antichità, del tardo paganesimo greco-romano: e, non a caso, essa è stata caratterizzata da una straordinaria angoscia esistenziale, da un senso di raccapriccio e di paura solo in séguito rischiarato da altre certezze. Ebbene l’inquietudine che caratterizza il mondo poetico di Poe appartiene a questo secondo tipo ed esprime, a nostro avviso, il dramma del passaggio dalla società pre-moderna alla piena modernità, caratterizzata dall’eclisse del sacro, dalla mercificazione totale dei rapporti umani, dall’efficientismo e dal produttivismo esasperati, dalla perdita del senso del limite e del mistero, dalla hybris (o dismisura) di un Logos strumentale e calcolante proteso ad affermare il suo dominio brutale sul mondo naturale, ridotto a pura riserva di beni da sfruttare e a discarica ove smaltire i prodotti di rifiuto del processo industriale. Nella letteratura anglo-americana dell’Ottocento, poi, vi è un significativo, assordante silenzio circa uno dei risvolti più terribili dell’avvento della modernità: lo sterminio del bisonte, lo sterminio dell’Indiano, vero peccatum originalis di una società nata all’insegna della democrazia e della tolleranza e che ha saputo distruggere, in pochi decenni, non solo una natura e una civiltà, ma un modo di essere, un modo di esprimere la sacralità delle cose (le Colline Nere del Dakota consacrate al Grande Spirito e prese d’assalto dall’uomo bianco in nome della sua insaziabile auri sacra fames di virgiliana memoria, la “maledetta brama dell’oro”). I grandi scrittori – Washington Irving, Hawthorne, Melville, Twain, Emerson, Thoreau, Whitman, lo stesso Poe – tacciono completamente al riguardo; pure in quel silenzio, in quella radicale rimozione, vi è un grido disperato, che è poi anche il grido del crimine commesso dall’uomo bianco contro se stesso, contro la parte migliore di sé, strangolata in nome del marcusiano homo oeconomicus.

Ma negli incubi e nei terrori dell’opera di Poe si direbbe prenda voce quel crimine rimosso, quel terribile silenzio della cultura “ufficiale”. Ed ecco i racconti del terrore di Poe, popolati da una umanità dolente e allucinata, i cui protagonisti sono altrettanti alter ego dell’autore, in cui ricorrono le sue funebri ossessioni: l’attrazione morbosa per la decadenza e la morte; la sepoltura da vivi e il ritorno dei non-morti; i torturanti sensi di colpa; la vendetta a lungo covata e ferocemente messa in opera; in una parola, il cupio dissolvi, il desiderio di auto-distruzione venato di sado-masochismo e di necrofilia, in una spirale sempre più asfittica e vorticosa, sempre più disperatamente chiusa in sé stessa.

Nel Manoscritto trovato in una bottiglia il protagonista, durante un viaggio per mare, viene trascinato dalla tempesta verso le estreme latitudini meridionali (come nel Gordon Pym), finchè il suo piccolo veliero è letteralmente travolto da una nave dalle dimensioni immense che si abbatte su di esso dall’alto di una formidabile ondata. Scaraventato a bordo della nave misteriosa, egli non tarda ad accorgersi che il suo equipaggio, che si comporta come se non lo vedesse affatto, è costituito in realtà da fantasmi, ovvero da esseri umani di un altro mondo, di un’altra dimensione. Vi è un’eco dantesca in questo racconto, un clima da epos della scoperta e della punizione che ricorda da vicino il “folle vollo” di Ulisse nel famoso XXVI canto dell’Inferno di Dante Alighieri; e anche una reminiscenza della celebre leggenda dell’Olandese Volante, il capitano di veliero del XVI secolo che, al passaggio del Capo di Buona Speranza, fu punito dalla giustizia divina per aver osato lanciare un’empia sfida alle leggi di Dio e della natura.

“Intendere l’orrore di ciò che io provo è, credo, assolutamente impossibile, e tuttavia una strana curiosità di penetrare i misteri di queste regioni spaventose ha il sopravvento persino sulla mia disperazione stessa, e certo mi riconcilierà con la visione della più orrida delle morti. È evidente che noi siamo spinti innanzi verso qualche affascinante conoscenza, verso qualche segreto mai rivelato ad alcuno, il raggiungimento del quale significa distruzione. Forse questa corrente ci conduce direttamente al Polo Sud, e devo ammettere che un’ipotesi apparentemente tanto avventata ha ogni probabilità in suo favore. Gli uomini dell’equipaggio si muovono sul ponte con passi inquieti, tremebondi, ma vi è nei loro volti una espressione più di attesa e di speranza che di apatia o di disperazione.

“Frattanto abbiamo senpre il vento in poppa e, poiché trasportiamo una mole incredibile di vele, il vascello è a volte sollevato di peso fuor del mare… Oh, orrore che non ha eguali! Il ghiaccio si apre subitamente a dritta e a manca, e noi stiamo roteando vorticosamente in immensi cerchi concentrici, torno torno agli orli di un gigantesco anfiteatro, il culmine delle cui muraglie si perde nelle tenebre e nella distanza. Ma poco tempo mi rimarrà per riflettere sul mio destino: i cerchi rimpiccioliscono rapidamente, stiamo inabissandoci a velocità pazzesca entro le fauci del vortice, e, fra un tumultuare, un muggire, un rombare di oceano e di tempesta, la nave vibra, scricchiola. Oh Dio!… Affonda!”

La situazione finale del Manoscritto viene poi pienamente sviluppata nel celebre Una discesa nel Maelstrom, ove l’orrore per le mostruose forze naturali scatenate quasi diabolicamente non è stemperato, ma anzi accresciuto dalla maniacale, incongrua lucidità con cui il protagonista – un pescatore travolto nel pauroso vortice norvegese, al laro delle Isole Lofoten – osserva ogni dettaglio della situazione e riesce perfino a coglire la dimensione estetica di quella muraglia d’acqua che si avvolge entro sé stessa – a coglierne lo spirito dell’orrido che, come pensava Schopenhauer, non è che una particolare situazione del sublime.

“Non potrò mai dimenticare il senso di terrore arcano, di orrore, di meraviglia che mi afferò non appena volsi lo sguardo a contemplare lo spettacolo che mi circondava. La barca sembrava sospesa a mezzavia, come per opera d’incantesimo, sulla superficie interna di un imbuto immenso di circonferenza, prodigioso di profondità, e le cui pareti perfettamente lisce potevano essere scambiate per ebano, non fosse stato per la rapidità vertiginosa con cui roteavano torno torno, e per la scintillante, spettrale radiosità che emanava da esse, quasi che i raggi della luna al suo colmo, da quello squarcio circolare frammezzo alle nubi che già ho descritto, sgorgassero in un fiotto di gloria dorata lungo le nere muraglie, giù, giù, sin entro i più riposti recessi dell’abisso”.

E ancora, si noti la selvaggia maestà di questo notturno lunare, degno di un Alcmane nella sua solenne, pensosa grandiosità, ma che altro non è, a ben guardare, se non un’ennesima trasposizione dell’incubo ricorrenti della sepoltura da vivo – una sepoltura liquida, nella tomba dell’oceano, non meno terrorizzante di quella in una solida bara, ma in qualche modo riscattata dalla sontuosa magnificenza spettrale che emana dalla scena nel suo insieme:

“I raggi della luna sembravano frugare in cerca del fondo stesso dell’insondabile abisso, ma io ancora non riuscivio a vedere distintamente, a causa di una fitta nebbia in cui ogni cosa era avvolta, e sulla quale si tendeva un meraviglioso arcobaleno simile all’angusto, vacillante ponte che i mussulmani dicono sia il solo passaggio tra il Tempo e l’Eternità. Questa foschia, o spuma, era senza dubbio prodotta dal cozzo delle grandi pareti dell’imbuto, ogni qualvolta esse si incontravano insieme nel fondo; ma l’ululato che saliva sino ai cieli fuor di quella nebbia io non mi arrischierò a descriverlo”.

Il protagonista de Una discesa, tuttavia, riesce miracolosamente a sopravvivere, legandosi a un barilotto e venendo poi tratto in salvo da alcuni pescatori: ma l’esperienza dell’orrido, del passaggio simbolico dal Tempo all’Eternità, lo ha segnato per sempre e precocemente invecchiato. Non è stata una morte e una rinascita di tipo iniziatico; egli è risalito dall’abisso svuotato di ogni energia, distrutto nel fisico e nello spirito. Per dirla col Nietzsche di Al di là del bene e del male: “Non puoi guardare a lungo nell’abisso, senza che l’abisso non finisca per guardare te dentro agli occhi”: e non è un’esperienza catartica, ma solo distruttiva.

“Coloro che mi issarono a bordo erano miei vecchi amici e compagni di tutti i giorni, ma non mi riconobbero più di quanto avrebbero riconosciuto un viaggiatore di ritorno dal mondo degli spettri: i miei capelli, che solo il giorno innanzi erano stati di un nero corvino, erano divenuti bianchi come tu li vedi adesso. Raccontai loro la mia avventura… ma non mi credettero. Io la ripeto a te… ma non spero che tu mi presti maggior fede di quanto me ne abbiano prestata gli allegri pescatori di Lofoten.”

Con il celeberrimo Il pozzo e il pendolo si passa da una dimensione di orrore naturale, cosmico, a un altro genere di orrore, diabolicamente umano – se ci è lecito l’ossimoro; la diabolica malignità che gli aguzzini dell’Inquisizione spagnola sanno escogitare a danno di un condannato, rinchiuso nelle loro carceri di Toledo. Dapprima l’uomo è gettato in una cella totalmente immersa nell’oscurità, ove per un puro caso evita di precipitare in un pozzo dalle profondità smisurate, insondabili, ove i suoi carnefici avrebbero voluto farlo precipitare; poi, dopo aver mangiato del cibo drogato, si risveglia legato ad un lettuccio, mentre un mostruoso pendolo dalla lama tagliente come un coltello affilatissimo, oscillando lentamente lungo tutta l’ampiezza della cella, scende millimentro dopo millimetro verso il suo petto indifeso. Egli vede avvicnarsi il terribile marchingegno ed è in grado di riflettere lucidamente, bevendo il terrore goccia a goccia e perfino calcolando quanti minuti ancora ci vorranno prima che la lama lo sfiori indi ne laceri lentamente la veste di sargia, infine gli apra il cuore. All’ultimo momento, con un misto di abilità calcolatrice e d’incredibile sangue freddo, egli riesce a liberarsi dai lacci e a sottrarsi al contatto fatale; ma solo per vedere le pareti metalliche della cella arroventarsi e poi deformarsi, restringendosi e sospingendolo sempre più verso una orribile morte. All’ultimo istante, quando tutto sembra perduto, il supplizio è interrotto. Le truppe francesi sono entrate a Toledo e il prigioniero è tratto in salvo, miracolosamente.

“La vibrazione del pendolo era ad angolo retto rispetto alla mia lunghezza. Compresi che la mezzaluna era stata disegnata per attraversare la regione del cuore. Avrebbe sfrangiato la sargia del mio saio… sarebbe ritornata, avrebbe ripetuto questa operazione… all’infinito. Nonostante la sua oscillazione di ampiezza terrificante (circa dieci metri e più) e il vigore sibilante della sua discesa, bastevole a fendere quelle stesse pareti di ferro, per parecchi minuti esso non avrebbe fatto che accentuare lo sfrangiamento della mia veste. E dinanzi a questo pensiero la mia mente sostò: non osavo andare oltre questa riflessione. Mi soffermai su questo punto con attenzione petinace… Come se in questo mio soffermarmi della mente potessi arrestare la discesa dell’acciaio. Mi forzai a pensare al brusio della mezzaluna quando fosse passata attraverso l’indumento, a quella particolare vibrante sensazione che il fruscio delle vesti produce sui nervi. Indulsi a questa frivola considerazione finché mi sentii allegare i denti.

“E intanto quell’orribile arnese scendeva… scendeva senza posa. Presi un piacere frenetico a paragonare la sua velocità discendente con quella laterale. A destra, a sinistra, innanzi, indietro, ululando come uno spirito dannato, sempre più presso al mio cuore con il passo felpato della tigre! Io alternavo le risate alle strida a seconda che predominasse questo o quel pensiero. “Giù… giù, inesorabilmente, sempre più giù! Vibrava ormai a soli pochi centimetri dal mio petto…”.

L’incubo della sepoltura da vivi è esplicitamente al centro del racconto Le esequie premature (come lo sarà in altri racconti, tra i quali Berenice, Ligeia e Il crollo della Casa Usher). Nella parte introduttiva di quest’opera, Poe sviluppa alcune riflessioni che potremmo definire filosofiche circa la difficoltà di delimitare con chiarezza la “zona grigia” che separa il regno della vita dal dominio della morte (precorrendo una analoga riflessione dell’epistemologo franco-polacco Mirko Grzimek, che alla morte e alla malattia ha dedicato, sul finire del Novecento, alcuni studi ormai entrati fra i classici del genere).

L’incubo della sepoltura da vivi è esplicitamente al centro del racconto Le esequie premature (come lo sarà in altri racconti, tra i quali Berenice, Ligeia e Il crollo della Casa Usher). Nella parte introduttiva di quest’opera, Poe sviluppa alcune riflessioni che potremmo definire filosofiche circa la difficoltà di delimitare con chiarezza la “zona grigia” che separa il regno della vita dal dominio della morte (precorrendo una analoga riflessione dell’epistemologo franco-polacco Mirko Grzimek, che alla morte e alla malattia ha dedicato, sul finire del Novecento, alcuni studi ormai entrati fra i classici del genere).

“L’infelicità vera, l’afflizione suprema è delimitata, non diffusa. E che le estreme ambasce dell’agonia siano sopportate dall’uomo individuo, non mai dall’uomo massa… sia ringraziato di questo un Dio misericordioso! Essere seppelliti ancora vivi è senza dubbio il più spaventoso di questi estremi che mai sia toccato in sorte a un essere mortale. Che ciò sia accaduto frequentemente, assai frequentemente, non sarà certo negato da color che pensano. I confini delimitanti la vita dalla Morte sono innegabilmente tenebrosi e vaghi. Chi può dire dove quella finisce e dove questa incomincia?”

Il racconto L’appuntamento è un gotico veneziano, un “notturno” dagli ingredienti un po’ convenzionali, sul quale non ci soffermeremo in questa sede. Ne approfittiamo invece per fare una riflessione di carattere generale. Non tutto quel che ha scritto Poe è arte; vi sono cose che ha scritto sotto l’urgenza della necessità economica (era “un forzato della penna”, un po’ come – in tutt’altro ambito e su tutt’altro piano – il nostro Emilio Salgàri -; e doveva fare i conti con i gusti del pubblico, che, in fatto di terrore, è sovente di palato alquanto grossolano. L’epoca in cui visse Poe è caratterizzata dall’avvento di una situazione del tutto nuova per lo scrittore. Scomparsa la committenza tradizionale, ora egli è a tu per tu con un pubblico molto più vasto ma anche più indifferenziato. Per tale ragione egli è più libero che in passato; ma anche, paradossalmente, più vincolato: perchè fra lui e il pubblico vi è il diaframma dell’industria editoriale, retta dalle ferree logiche del mercato (ancora la produzione, ancora l’homo oeconomicus: vera e grande maledizione della modernità); ed è essa il suo concreto interlocutore. Poe, per carattere e per convinzioni, intendeva l’arte come una sfera del tutto autonoma, e della sua arte di scrittore volle vivere, fin da giovanissimo, affrontando ogni sorta di difficoltà per non dover scendere a compromessi; ma è un fatto che i compromessi, specialmente come giornalista, dovette accettarli, in maggiore o minor misura; e la sua vasta opera letteraria, nella sua differente qualità artistica, ne mostra i segni più d’una volta. Ma torniamo ai racconti del terrore.

Con Berenice entriamo nel vivo di uno dei temi dominanti delle sue ossessioni erotiche: l’attrazione-repulsione per la donna esangue, spettrale, vera e propria controfigura della morte e della propria ansia di auto-distruzione; donna verso la quale si sente attratto – come il protagonista del notevole romanzo Fosca dello scapigliato Iginio Ugo Tarchetti – non già a dispetto dei segni evidenti della malattia, del decadimento e della prossima fine, ma appunto per quei segni: confine sottile, e tuttavia decisivo, fra l’eros “normale” e l’eros “sadico-anale” (direbbe Freud). Non aveva forse sostenuto, Poe, nella sua Filosofia della composizione, che “la morte di una bella donna è senza dubbio l’argomento più poetico del mondo”? (Del resto, questione di gusti; Virgilio, dal canto suo, avrebbe certamente ribattuto che l’argomento più è offerto dalla morte dei bei giovinetti, come i vari Eurialo, Niso, Lauso e Pallante attestano, imperversando nella seconda parte dell’). Sicché il binomio Eros- Thanatos, in Poe, non è mai direzionato dal primo al secondo elemento, bensì, immancabilmente, dal secondo al primo: è attraverso il presentimento della loro morte vicina che i protagoinisti maschili dei suoi racconti – indifferenti o solo distaccatamente ammirati in senso estetico allorché le fanciulle, agili e leggiadre, godevano di apparente buona salute – s’infiammano poi di un sinistro, incofessabile desiderio; spesso concentrato non sull’insieme della loro persona, ma – feticisticamente – su un particolare anatomico, su un dettaglio, come i denti, appunto, in Berenice, o gli occhi in Ligeia; e, per quel dettaglio, arrivano a compiere azioni orribili e inconfessabili.Eneide

“Era frutto della mia immaginazione eccitata, o dell’influenza nebbiosa dell’atmosfera, o del crepuscolo incerto della stanza, o erano forse i grigi panneggi che cadevano in pieghe attorno alla sua figura, che provocavano in questa un aspetto così vacillante e vago?- si chiede, con sgomento, il protagonista di Berenice. – “Non saprei dire. Ella non proferiva parola, e io… neppure con uno sforzo sovrumano sarei riuscito a pronunciare una sola sillaba. Un brivido di ghiaccio mi corse per le ossa; mi sentii opporesso da una sensazione d’insopportabile angoscia; una curiosità divorante mi pervase l’anima, e ricadendo all’indietro sulla sedia rimasi per qualche tempo immobile e senza fiato, gli occhi fissi sulla sua persona. Ahimé! La sua emaciatezza era estrema, e in tutto il suo aspetto non vi era più neppure una lontana traccia dell’antica creatura. Alla fine il mio sguardo bruciante si posò sul suo viso.

“La fronte era alta, pallidissima, stranamente serena.; e i capelli un tempo color del giaietto ricadevano parzialmente su di essa adombrando le tempie cave d’innumerevoli riccioli ora d’un giallo vivo e sgradevolmente discordanti nel loro fantastico aspetto con la malinconia predominante nelle sembianze di lei. Gli occhi erano senza vita, opachi, apparentemente privi di pupille, e io mi ritrassi involontariamente dalla loro vitrea fissità per contemplare le labbra sottili, affilate. Queste si aprirono, e in un sorriso di particolare significato i denti della mutata Berenice si dischiusero lentamente ai miei occhi. Volesse il cielo che io non li avessi veduti, o che dopo quell’attimo in cui io li vidi, fossi morto!”

Poco dopo Berenice muore e viene sepolta, forse con troppa precipitazione; ma ormai l’anima del protagonista è irrimediabilmente stregata dalla visione di quei denti bianchissimi, che la possiedono per mezzo di un fascino malsano. Nella pagina finale del racconto, la scena acquista gradualmente l’orribile chiarezza di una rivelazione che coglie di sorpresa lo stesso protagonista: in stato di sonnambulismo, egli si rende conto di aver commesso un atto esecrando e indicibile.

“Sul tavolo accanto a me bruciava una lampada, e accanto a questa era posata una piccola scatola. Non presentava alcuna caratteristica particolare e già io l’avevo veduta molte altre volte, essendo di proprietà del nostro medico di famiglia; ma come era venuta a finire lì, sul mio tavolo, e perché rabbrividivo nel guardarla? Non sapevo in alcun modo spiegarmi questo mio stato d’animo, finché i miei occhi caddero sulle pagine aperte di un libro, e precisamente su una frase sottolineata in esso. Erano le strane e pur semplici parole del poeta Ebn Zaiat: ‘Dicebant mihi sodales si sepulchrum amicae visitarem, curas mea aliquantulum fore levatas.‘ Perché dunque nello scorrere quelle poche righe i capelli mi si rizzarono sul capo, e il sangue del mio corpo si rallegrò entro le mie vene?

“In quella si intese all’uscio della biblioteca un bussare sommesso, e pallido come l’abitante di una tomba un domestico entrò in punta di piedi. Aveva lo sguardo alterato dalla paura, e si rivolse a me con voce tremante, soffocata, bassissima. Che cosa mi disse? Non afferrai che alcune frasi rotte. Mi narrò di un grido forsennato che aveva squarciato il silenzio della notte, che i familiari si erano radunati, che ricerche erano state fatte in direzione del grido, e a questo punto i suoi accenti divennero paurosamente distinti, mentre egli mi sussurrava di una tomba violata, di un corpo avvolto nel sudario sfigurato, eppure ancora respirante, ancora palpitante, ancora vivo. Parlando, il domestico appuntò l’indice contro i miei abiti; erano coperti di fango, e tutti ingrommati di sangue. Io non parlai, ed egli mi prese dolcemente la mano: era tutta segnata dall’impronta di unghie umane. Rivolse quindi la mia attenzione a un oggetto appoggiato contro la parete; lo fissai per alcuni minuti: era una vanga. Con un urlo, balzai verso il tavolo, afferrai la scatola che vi era posata sopra. Non ebbi però la forza di aprirla; tremavo tanto che essa mi scivolò di mano e cadde pesantemente frantumandosi in mille pezzi. Da essa, con un rumore secco, crepitante, uscirono rotolando alcuni strumenti di chirurgia dentaria, mescolati a trentadue piccole cose bianche, eburnee, che si sparsero qua e là sul pavimento.”

Dunque, l’uomo ha strappato uno ad uno i denti di Berenice, lottando con la donna ancor viva, ridestata – probabilmente – dal dolore provocatole; e venendo da lei graffiato; poi ha riportato in casa, e nascosto nella scatoletta, il suo prezioso e innominabile bottino. Il risvolto più intrigante del racconto sta proprio in questa dimensione inconscia dell’io del protagonista: il quale scopre, con raccapriccio, di aver fatto qualcosa che la sua coscienza desta non avrebbe mai osato nemmeno concepire.

In Berenice, quindi, manca l’elemento soprannaturale del terrore; in Morella esso è adombrato alla fine della vicenda perché, dopo aver sepolto successivamente la moglie e, molti anni dopo, la figlia – a lei terribilmente somigliante, e alla quale aveva imposto lo stesso nome -, il protagonista maschile scopre che la bara della “prima” Morella era vuota e si rende così conto che la “seconda” non era altri che la donna ritornata, inesplicabilmente, dall’altro mondo. Morella, diafana e taciturna creatura immersa nella scienza proibita di saperi antichissimi, prima di ammalarsi esercita uno strano fascino intellettuale sull’uomo, fascino che diviene apertamente sensuale solo dopo la morte di lei.

“In seguito, allorché, meditando assiduamente su pagine proibite, io sentivo accendersi entro di me uno spirito proibito, Morella soleva porre la sua fredda mano sulla mia, e frugare tra le ceneri di una filosofia morta qualche strana, singolare parola, il cui misterioso significato s’imprimeva bruciante nella mia memoria. Allora, per ore e ore, io indugiavo al suo fianco, inebriandomi della musica della sua voce, sino a quando, a un tratto, la sua musicalità si soffondeva di terrore. Allora un’ombra cadeva sulla mia anima, e io impallidivo e rabbrividivo interiormente a quegli accenti troppo ultraterreni. Allora la gioia si tramutava improvvisamente in orrore, e il supremamente bello si faceva ributtante, così come Hinnon divenne Gehenna”.

Ancora una volta, dunque, la linea ambigua e sottilissima che separa il sublime dall’orrido; ma, questa volta, considerata nel suo movimento dal primo al secondo, e non viceversa (come nel paesaggio naturale de Una discesa nel Maelstrom). La parte più intensa e originale del racconto, tuttavia, è quella in cui Poe descrive il sentimento torbido, tenebroso con cui il protagonista segue le ultime fasi della malattia mortale di Morella (la prima), attendendone la morte con un inconfessabile desiderio di liberazione – primo seme di quel futuro senso di colpa che, come nel caso di Roderick Usher, renderà particolarmente amari e terribili i giorni successivi al funebre evento.

“Dovrò dunque dire che attendevo con un desiderio ansioso, divorante, il momento del trapasso di Morella? Eppure è vero, ma il fragile spirito si avviticchiò al suo abitacolo di creta, per molti giorni, per molte settimane e tediosi mesi, sino a che i miei nervi tormentati ottennero il dominio della mia mente, e il ritardo mi infuriò, e con cuore demoniaco maledissi i giorni, le ore, gli amari momenti che sembravano allungarsi senza fine mentre la sua dolce vita declinava così come si allungano le ombre nello smorire del giorno”.

Il binomio Eros-Thanatos si colora qui di evidenti tracce di sadismo e di inconscia necrofilia, poiché desiderare l’affrettarsi della morte di Morella significa anche pregustare il momento in cui ella non sarà che un corpo abbandonato, indifeso, un corpo interamente alla mercé del maschio: così come il corpo di Pentesilea, dopo essere stato trafitto a morte, accende il desiderio di Achille sotto le mura di Troia, e lo spinge all’estremo oltraggio della sua postuma bellezza.

Il binomio Eros-Thanatos si colora qui di evidenti tracce di sadismo e di inconscia necrofilia, poiché desiderare l’affrettarsi della morte di Morella significa anche pregustare il momento in cui ella non sarà che un corpo abbandonato, indifeso, un corpo interamente alla mercé del maschio: così come il corpo di Pentesilea, dopo essere stato trafitto a morte, accende il desiderio di Achille sotto le mura di Troia, e lo spinge all’estremo oltraggio della sua postuma bellezza.

In Ligeia, il particolare anatomico che scatena il morboso interesse del protagonista sono gli occhi; e Ligeia, del resto, si rivelerà una donna-vampiro, una non-morta (ispirando, probabilmente, il filone baudelaireiano della donna-vampiro nei Fleurs du Mal): non una vittima, come la sventurata Berenice, bensì una creatura immortale e pericolosa.

“Senza Ligeia ero come un bambino che si aggira tastoni la notte. La sua presenza, le sue letture semplicemente, rendevano vividamente luminosi i molteplici misteri del tradscendentalismo nel quale eravamo immersi. Senza il radioso splendore dei suoi occhi, le lettere, fiammee e dorate, divenivano più opache del piombo saturnio. Ed ecco che quegli occhi brillarono sempre meno di frequente sulle pagine da me compulsate. Ligeia si ammalò. I suoi occhi smarriti lucevano di un troppo… troppo glorioso fulgore: le pallide dita di lei assunsero la translucida cereità della tomba, le vene azzurrine della sua eccelsa fronte si inturgidivano e si afflosciavano d’impeto con l’avvicendarsi della finanche più lieve emozione. Compresi che ella sarebbe morta, e lottai disperatamente in ispirito con il funebre Azrael.”

Più tardi, alla morte di Ligeia, il protagonista ne veglia penosamente il cadavere; ma è una notte di orrore in cui l’impensabile può accadere, in cui i morti possono ridestarsi.

“Il cadavere, ripeto, si muoveva, e adesso più energicamente delle altre volte. I colori della vita ne invermigliavano con inconsueta energia il volto, le membra si rilassarono e, tranne che per le palpebre ancora pesantemente abbassate e per le acconciature e i panneggiamenti tombali che ancora davano alla figura un aspetto macabro, io avrei potuto immaginare che Rowena si fosse davvero liberata e per sempre dai legami della Morte. Ma se io non potevo accettare del tutto questa realtà neppure in quel momento, non mi fu più possibile dubitare allorché, levandosi dal letto, e vacillando con deboli passi, con occhi chiusi,, con l’atteggiamento di chi è reso attonito da un sogno, la cosa avvolta nel sudario avanzò audacemente, tangibilmente, sin nel mezzo della stanza”.

Ne Il crollo della casa degli Usher esiste una misteriosa, inesplicabile relazione tra l’antica dimora immersa nella nebbia dello stagno che la circonda, fatta di antichissime pietre solcate da una fenditura quasi impercettibile, e tuttavia nettissima, che l’attraversa tutta obliquamente; l’ultimo rampollo dell’antica casata, sir Roderick, sfibrato da una indefinibile malattia, o meglio somma di malattie, consistente – oltre che in una sindrome maniaco-depressiva, in una estrema, sorprendente acutizzazione dei cinque sensi, per cui egli può indossare solo abiti di un certo tessuto e vive nell’eterna penombra, al riparo da luci e da suoni troppo forti (dato che percepisce nettamente anche quelli più impercettibili); e la sorella gemella di lui, lady Madeline, a sua volta afflitta da una sconosciuta malattia, pallido fantasma che si spegne pochi giorni dopo l’arrivo del narratore, un vecchio amico d’infanzia di Roderick chiamato da una lettera d’aiuto quasi disperata. Il racconto è stato sezionato ed analizzato in termini di psicanalisi classica da un’allieva diretta di Freud, Maria Bonaparte, principessa di Grecia; colei che aiutò il maestro a fuggire dall’Austria invasa dai nazisti mediante l’Anschluss del 1938. Per lei, il dramma di Poe – qui sdoppiato nei due personaggi di Roderick e del narratore – consiste nell’amore incestuoso per la sorella e nel tradimento della madre (la madre perduta nella prima infanzia, “tradita” simbolicamente con la sposa-bambina Virginia), dunque in un senso di colpa che culmina nella catastrofe finale, in cui Roderick, Madeleine e la casa- utero di entrambi vengono distrutti simultaneamente. Anche qui, infatti, abbiamo una sepoltura affrettata della sventurata Madeline; anche qui la morta si ridesta per tornare dal fratello e condurlo a morte con sé, vittima del terrore che la sua apparizione gli suscita.

“Durante un giorno triste, cupo, senza suono, verso il finire dell’anno, un giorno in cui le nubi pendevano opprimentemente basse nei cieli, io avevo attraversato solo, a cavallo, un tratto di regione singolarmente desolato, finché ero venuto a trovarmi, mentre già si addensavano le ombre della sera, in prossimità della malinconica Casa degli Usher. Non so come fu, ma al primo sguardo che io diedi all’edificio, un senso intollerabile di abbattimento invase il mio spirito. Dico intollerabile poiché questo mio stato d’animo non era alleviato per nulla da quel sentimento che per essere poetico è semipiacevole, grazie al quale la mente accoglie di solito anche le più tetre immagini naturali dello sconsolato e del terribile. Contemplai la scena che mi si stendeva dinanzi, la casa, l’aspetto della tenuta, i muri squallidi, le finestre simili a occhiaie vuote, i pochi giunchi maleolenti, alcuni bianchi tronchi d’albero ricoperti di muffe: contemplai ogni cosa con tale depressione d’animo ch’io non saprei paragonarla ad alcuna sensazione terrestre se non al risveglio del fumatore d’oppio, l’amaro ritorno alla vita quotidiana, il pauroso squarciarsi del velo. Sentivo intorno a me una freddezza, uno scoramento, una nausea, un’invincibile stanchezza di pensiero che nessun pungolo dell’immaginazione avrebbe saputo affinare ed esaltare in alcunché di sublime. Che cos’era, mi soffermai a riflettere, che cos’era che tanto m’immalinconiva nella contemplazione dela Casa degli Usher?”

Nel corso di un drammatico colloquio, Roderick fnisce per rivelare all’amico -in parte – i terrori paurosi di cui è vittima, e profetizza l’approssimarsi della propria, inevitabile fine.

“Mi avvidi che era schiavo, legato mani e piedi, di una forma anomala di terrore. “Io morirò – mi disse – dovrò morire in questa disperata follia. Così, così, non altrimenti, mi perderò. Temo gli avvenimenti del futuro non di per se stessi, ma per i loro risultati. Rabbrividisco al pensiero di un fatto qualsiasi, anche il più comune, che possa operare su questa agitazione intollerabile del mio spirito. In realtà non rifuggo dal pericolo, se non nel suo effetto assoluto, cioè il terrore. In questo senso di smarrimento dei nervi, in questa pietosa condizione, temo che spraggiungerà presto o tardi il momento in cui mi vedrò costretto ad abbandonare la vita e la ragione insieme in qualche conflitto con il sinistro fantasma della paura”.

Ma non è un fatto qualsiasi, non è un conflitto con un fantasma indifferenziato quello che porta Roderick Usher alla rovina, bensì un evento preciso e una colpa (o un desiderio) inconfessabile: le esequie premature della sorella e il ritorno vendicativo di lei dalla cripta ove il suo corpo è stato momentaneamente deposto, in attesa della sepoltura definitiva. Durante una notte da tregenda, quando la tempesta spazza la casa e l’aria è satura di elettricità e di bagliori delle scariche temporalesche, l’amico cerca disperatamente di distrarre le angosce inenarrabili del padrone di casa e gli legge – invero poco opportunamente – la drammatica storia di Etelredo, l’eroe celtico; storia il cui finale sembra ricalcare e rievocare i terrori da cui l’animo di Roderick è sempre più turbato. Alla fine, questi erompe in un grido di disperazione e di raccapriccio:

“Non l’ho udito? Certo che l’ho udito! E lo odo ancora. Da tanto… tanto… tanto. Da molti minuti, da molte ore, da molti giorni, io lo odo, e tuttavia non ho osato… oh, pietà di me, miserabile sciagurato che sono! Non osavo… non osavo parlare! L’abbiamo calata nella tomba viva! Non ti dicevo che i miei sensi sono acutissimi? Ebbene ti dico adesso che io ho inteso persino i suoi primi deboli movimenti nella cavità del sarcofago. Vi ho avvertiti… molti, molti giorni fa… e tuttavia non osavo… non osavo parlare! Ed ecco che… stanotte… Ethlred… Ah! Ah! L’abbattersi dell’uscio dell’eremita, e l’urlo di morte del drago, e il clangore dello scudo!… Vuoi dire piuttosto l’infrangersi della sua bara, il suono stridente dei cardini di ferro della sua prigione, il suo dibattersi entro l’arcata foderata di rame della cripta! Oh, dove fuggire? Non sarà ella qui tra poco? Non sta forse affrettandosi per rimproverarmi la mia precipitazione? Forse che non ho inteso il suo passo sulle scale? Non distinguo forse lo spaventoso pesante battito del suo cuore? Pazzo! – A questo punto balzò in piedi come una furia e urlò queste parole come se nello sforzo esalasse tutta la sua anima: – Pazzo! Ti dico che ella sta ora in piedi fuori dell’uscio!

“Quasi che la sovrumana energia della sua voce contenesse la potenza evocatrice di un incantesimo, gli enormi antichi pannelli che egli additava, dischiusero lentamente, in quel medesimo istante, le loro poderose nere fauci. Fu senza dubbio l’opera dell’uragano infuriante; ma ecco che fuor di quell’uscio si ergeva veramente l’alta ammantata figura di lady Madeline Usher. Il suo bianco sudario era macchiato di sangue, e su tutto il suo corpo emaciato apparivano evidenti i segni di una disperata lotta. Per un attimo ella rimase tremante, vacillante sulla soglia, poi con un gemito sommesso e prolungato cadde pesantemente sul corpo del proprio fratello e nei suoi violenti e ormai supremi spasimi agonici lo buttò al suolo cadavere, vittima dei giustificati terrori che lo avevano agitato”.

“Da quella camera e da quella casa io fuggii inorridito. L’uragano infuriava ancora in tutta la sua collera mentre io attraversavo l’antico sentiero selciato. A un tratto rifulse sul viottolo una luce abbagliante e io mi volsi a guardare donde poteva provenire un così insolito fulgore, poiché dietro di me avevo soltanto l’immensa casa e le sue ombre. Il chiarore proveniva dalla luna calante, al suo colmo, sanguigna, che ora splendeva vividamente attraverso quell’unica fessura appena discernibile di cui ho già parlato e che si stendeva dal tetto dell’edificio in direzione irregolare, serpeggiante, sino alla sua base. Mentre guardavo, questa fessura rapidamente si allargò, il turbine di vento infuriò in supremo anelito, tutta l’orbita del pianeta si rivelò improvvisa alla mia vista, il mio cervello vacillò, mentre i miei occhi vedevano le possenti mura spalancarsi, s’intese un lungo tumultuante urlante rumore simile al frastuono di mille acque, e il profondo fangoso stagno ai miei piedi si chiuse cupo e silenzioso sui resti della Casa degli Usher”.

Nel racconto La maschera della Morte Rossa, di ambientazione apparentemente italiana, si narra di come il principe Prospero si rinchiude con un migliaio di amici e cortigiani in un formidabile castello, follegggiando di festa in festa mentre, tutt’intorno, una spaventosa epidemia di peste falcidia la popolazione, trasformando le sue vittime in altrettante orribili maschere, rosse per le chiazze sanguinolente che si diffondono su tutto il corpo. Ma un giorno, al culmine della festa, mentre un orologio batte ossessivamente le ore della notte suscitando oscuri presentimenti, un ospite sconosciuto si presenta ai convitati, vestito con le lacere vesti e con le orrende sembianze della Morte Rossa, suscitando un generale moto d’indignazione e di orrore.

“Anche per gli esseri più perduti, per i quali la vita e la morte sono egualmente motivo di beffa, esistono cose di cui non è possibile beffarsi. Tutti gli astanti insomma sentivano ormai che nel costume e nel portamento dello straniero non vi erano né spirito né decenza. La figura era alta e scarna, e avvolta da capo a piedi nei vestimenti della tomba. La maschera che ne nascondeva il viso era talmente simile all’aspetto di un cadavere irrigidito che anche l’occhio piiù attento avrebbe stentato a scoprire l’inganno. Eppure tutto ciò avrebbe potuto essere sopportato, se non approvato, dai gaudenti forsennati che si aggiravano per quelle sale: ma il travestimento aveva spinto tant’oltre la sfrontatezza da assumere le sembianze della ‘morte rossa’. Le sue vesti erano intrise di sangue, e la sua vasta fronte e tutti i lineamenti della sua faccia erano spruzzati dell’orrore scarlatto”.

Sdegnato, il principe ha un moto di ribellione, ma un inspiegabile terrore lo paralizza, insieme ai cortigiani, mentre lo straniero si allontana in mezzo ai convitati, attraversando una dopo l’altra le sette stanze colorate di un’ala poco frequentata del castello: la sala turchina, poi la purpurea, la verde, l’arancione, la bianca, la violetta e, ultima, la paurosa sala nera, done provengono i sinistri rintocchi dell’orologio a pendolo. Il principe Prospero, riavutosi dallo smarrimento e reso pazzo dalla vergogna per quella momentanea viltà, si slancia all’inseguimento armato di spada; ma, raggiunto lo straniero nella sala nera, un urlo d’agonia esce strozzato dalla sua gola, e il suo corpo si abbatte al suolo senza vita. Allora, raccogliendo il coraggio della disperazione, i suoi cortigiani si precipitano a loro volta nella sala decisi a vendicarlo, ma solo per rendersi conto, con inesprimibile terrore, che lo straniero non è affatto vestito in maschera: sotto il sudario non c’è alcuna forma tangibile, poiché egli è la Morte Rossa in persona, ed è giunto fra loro per perderli tutti.

“E allora tutti compresero e riconobbero la presenza della Morte Rossa giunta come un ladro nella notte, e ad uno ad uno i gaudenti giacquero nelle sale irrorate di sangue delle loro gozzoviglie, e ciascuno morì nell’atteggiamento disperato in cui era caduto. E la vita della pendola d’ebano si estinse con quella dell’ultimo dei baldorianti. E le fiamme dei tripodi si spensero. E l’Oscurità, la Decomposizione e la Morte Rossa regnarono indisturbate su tutto”.

Ne Il cuore rivelatore non compare alcun elemento soprannaturale, si tratta di una storia basata unicamente sulla psiche malata del protagonista; pure, Poe sa tendere a un punto tale l’arco della lucida, ossessionante analisi dei meandri tortuosi della psiche umana, da conferire al racconto un tono altamente impressionante e drammatico. Un vecchio ha preso in casa un giovane uomo, non si sa bene se come figlio adottivo o come servitore; ma quest’ultimo è letteralmente ossessionato da un particolare anatomico del padrone di casa: un occhio dalla palpebra velata, che gli ricorda un orribile occhio di avvoltoio. Il pregio maggiore di questo racconto consiste nel contrasto fra l’estrema, meticolosa lucidità con cui il protagonista analizza la situazione, agisce e descrive i fatti, e con cui rifiuta di essere considerato pazzo “perché i pazzi non sanno di esserlo”, mentre lui “ode tutte le cose del cielo e della terra” (vengono in mente le “voci” dei grandi santi e dei mistici, e come sia sottile il filo che le separa da stati di coscienza alterati di origine patologica), e l’abisso di feroce follìa omicida in cui egli si abbandona, andando incontro al suo inevitabile destino di auto-distruzione.

” È impossibile dire come l’idea mi sia entrata per la prima volta nel cervello. Ma non appena l’ebbi concepita mi ossessionò notte e giorno. Scopo non ne avevo. Odio neppure. Volevo bene al vecchio. Non mi aveva mai fatto del male. Non mi aveva mai insultato. Non desideravo il suo oro. Credo fosse il suo occhio! Sì, fu proprio così! Aveva l’occhio di un avvoltoio,un occhio pallido azzurro, coperto di una pellicola. Ogni volta che esso si posava su di me il mio sangue si raggelava, e così per gradi, oh, per gradi molto lenti, io decisi di togliere la vita al vecchio, e sbarazzarmi così per sempre di quell’occhio”.

Di notte, quando il vecchio dorme, il protagonista si avvicina piano piano alla sua camera, ne socchiude l’uscio con infinite precauzioni, indi proietta il raggio di una lanterna cieca sull’occhio di avvoltoio, restando inorridito e affascinato a contemplarlo, per ore ed ore.

Per sette notti consecutive, a mezzanotte, il folle rito si ripete: l’uomo ha già deciso di compiere il delitto, ma ogni volta rimanda, perché nel sonno l’occhio del vecchio rimane chiuso e appare normale; e non è il vecchio ch’egli vuole uccidere, ma il suo Occhio. Chi ha un poco di familiarità con le pagine della cronaca nera di questi ultimi anni avrà colto l’analogia con alcuni tremendi delitti, originati da una fissazione maniacale da parte dell’omicida, convinto di essere inesplicabilmente ma mortalmente minacciato da qualcosa che risiede nella sua vittima, qualcosa che egli non sa precisare, ma che “le voci” gli ordinano di eliminare per sempre. In genere, si tratta di delitti maturati nell’ambiente della magia nera e degli adoratori del diavolo: le “voci”, in questi casi, svolgono una lenta, metodica istigazione al delitto. Delitto che resta inspiegabile in termini razionali, poiché non è giustificato da moventi razionalmente riconoscibili; e anche il furto, ammesso che vi sia, non appare che una messa in scena per dare plausibilità all’assassinio. Ma nel racconto di Poe le “voci” non sono meglio precisate, e nulla suggerisce che vi sia un’ispirazione diabolica o un qualunque elemento soprannaturale. Anche la percezione dei battiti del cuore, che – come suggerisce già il titolo del racconto – provocheranno la scoperta del delitto, può avvenire solo nella fantasia malata del protagonista, sconvolto dal senso di colpa e da oscure manie di persecuzione.

“Dopo aver aspettato a lungo, con infinita pazienza, senza averlo udito riadagiarsi, decisi di socchiudere, oh, appena appena, una sottilissima fenditura nella lanterna. L’aprii dunque, non potete immaginare con quanta, quanta cautela, sinché un sottilissimo tenuissimo raggio, simile al filo d’un ragno, balzò fuor della fenditura e cadde in pieno sull’occhio d’avvoltoio. Era aperto, tutto aperto, completamente spalancato, e nel fissarlo la furia mi invase. Lo vedevo distintissimamente, tutto di un azzurro opaco, con quell’odioso velo che lo ricopriva e che faceva raggelare persino il midollo delle mie ossa; ma non potevo vedere altro del vecchio, né della sua faccia, né del suo corpo, poiché avevo rivolto il raggio come per istinto su quell’unico maledetto punto”.

Così, destato dal rumore, il vecchio si sveglia e grida spaventato, spalancando l’occhio deforme; e il protagonista, infuriato a quella vista, si slancia contro di lui e lo sopprime. Poi, davanti ai poliziotti che alcuni vicini hanno indirizato in quella casa, recita con perfetto sangue freddo la commedia dell’ignaro domestico: li invita a visitare l’abitazione, a fugare ogni sospetto. I resti del vecchio, atrocemente sezionato, giacciono sotto i palchetti di legno del pavimento, e quest’ultimo è stato ripulito e riassestato così bene, che nulla all’esterno trapela. Spinto da una baldanza insensata, da un isterico desiderio di trionfo, l’uomo trattiene deliberatamente i poliziotti, soffermandosi proprio nel punto ove giacciono i macabri resti. Ma ecco che al suo udito finissimo e sovreccitato cominciano a giungere i battiti del cuore della sua vittima: assurdamente, inspiegabilmente; e divengono sempre più forti, sempre più forti. Per un po’ egli tenta di coprirli con le sue parole; ma intanto una crescente agitazione si impadronisce di lui, e i suoi gesti e i suoi discorsi si fanno sempre più strani e alterati. Alla fine il battito è divenuto un rombo assordante, ed egli è convinto che anche gli altri lo odano, ma fingano il contrario per farsi beffe di lui, per deriderlo.

“Senza dubbio dovevo essere diventato pallidissimo, ma seguitavo a discorrere sempre più animatamente, a alzando il tono della mia voce. Nondimeno il rumore aumentava, e che cosa potevo fare? Era un rumore sommesso, soffocato, veloce, assomigliava moltissimo al rumore che fa un orologio quando è avvolto nel cotone. Ansimai: mi sentivo il fiato mozzo; e tuttavia i poliziotti non lo avevano avvertito. Parlai ancora più in fretta, con irruenza ancora maggiore, ma il rumore aumentava inesorabilmente. Mi alzai e presi a discutere di sciocchezze, in tono di voce altissimo e gesticolando violentemente, ma il rumore cresceva implacabile. Perché non se ne andavano? Incominciai a passeggiare innanzi e indietro a lunghi passi, quasiché i discorsi di quegli uomini mi avessero infuriato, ma il rumore cresceva, cresceva sempre. Oh, Dio! Che cosa potevo fare? Schiumavo, vaneggiavo, bestemmiavo! Volsi di scatto la seggiola su cui mi ero messo a sedere, la trascinai sulle tavole, ma il rumore copriva ogni cosa aumentando continuamente. Si faceva sempre più forte, sempre più forte, sempre più forte! E tuttavia gli uomini seguitavano a discorrere piacevolmente, e sorridevano. Era mai possibile che non udissero? Dio onnipotente! No, no! Certo che lo udivano! Sospettavano! Sapevano! Si beffavano della mia disperazione! Questo pensai, e questo penso. Ma qualsiasi cosa era meglio dell’angoscia mortale che mi attanagliava! Qualsiasi cosa era più tollerabile di quella derisione! Non potevo più sopportare quei sorrisi ipocriti! Compresi che dovevo urlare o altrimenti sarei morto! Ed ecco, ancora! Ascoltate! Più forte! Più forte! Più forte! Più forte!

“- Mascalzoni! – urlai, – smettetela di fingere! Confesso il delitto! Togliete quelle tavole! Qui, qui! È il battito del suo odioso cuore!”

La situazione finale de Il cuore rivelatore si ritrova in un altro celebre racconto del terrore di Poe, Il gatto nero. Qui un uomo, dedito all’alcool e ai disordini, dapprima uccide crudelmente il proprio gatto, impiccandolo a un albero; poi si salva a stento dall’incendio della propria casa, mentre sulla parete semi-carbonizzata appare la sagoma gigantesca di un gatto. Più tardi, trova per caso, all’osteria, un altro gatto, misteriosamente identico al primo, e lo porta con sé nella nuova casa. Qui, in un momento di furore, cava un occhio alla bestia e subito dopo, con una scure, assassina la propria moglie e nasconde il cadavere, murandolo dietro una parete. Anche qui si presentano i poliziotti per fare delle indagini: ispezionano la casa (il gatto, frattanto, è scomparso), ma non trovano nulla e stanno per andarsene, quando avviene la terribile rivelazione.

“Signori – dissi infine, mentre già stavano salendo i gradini – sono lieto di avere calmato i vostri sospetti. Vi auguro buona notte, e vi porgo i miei omaggi. A proposito, signori, questa… questa è una casa costruita meravigliosamente bene – (Nel desiderio morboso di parlare con disinvoltura, quasi non mi rendevo conto delle parole che proferivo). Posso dire anzi che è una casa costruita in maniera eccellente. Queste pareti, ve ne state già andando, signori?, queste pareti, guardate come sono solide! – E a questo punto, in una vera frenesia di sfida, picchiai pesantemente con la mazza che tenevo in mano proprio su quel tratto di opera muraria dietro il quale stava il cadavere della moglie che io avevo tanto amata.

“Ma possa Iddio proteggermi e liberarmi dagli artigli dell’Arcidemonio! Non appena gli echi dei miei colpi si furono spenti nel silenzio, ecco che ad essi una voce rispose dal segreto loculo! Era un pianto, dapprima soffocato e interrotto, come il singhiozzare di un bambino che rapidamente si enfiò sino a divenire un unico lungo, alto, continuo urlo, indicibilmente strano e inumano, un ululato, uno stridio guaiolante, per metà di orrore e per metà di trionfo, quale solo avrebbe potuto levarsi dal fondo dell’inferno, se le gole di tutti i dannati nella loro angoscia e tutti i demoni nell’esultanza della dannazione umana si fossero insieme congiunte.

“Di quel che fossero i miei pensieri in quel momento è follia parlare. Sentendomi venir meno, arretrai barcollando verso la parete opposta. Per un attimo i poliziotti, giunti in cima alle scale, ristettero immobili, raggelati dall’orrore e da una specie di acana paura. Un attimo dopo dodici braccia robuste si davano da fare attorno alla parete. Questa cadde di colpo in tutta la sua massa. Il cadavere, già quasi interamente decomposto e chiazzato di sangue raggrumato, apparve eretto dinanzi agli occhi degli agenti. Sul suo capo, con la rossa bocca spalancata e l’unico occhio di fiamma, sedeva lo spaventoso animale la cui malizia mi aveva indotto al delitto, e la cui voce rivelatrice mi aveva consegnato al boia. Avevo murato il mostro entro la tomba!”

Se l’uccisione del primo gatto (e la mutilazione del secondo) può ricordare l’uccisione dell’albatro ne La ballata del vecchio marinaio di Samuel Taylor Coleridge, la scoperta del delitto rimanda ai racconti polizieschi dello stesso Poe, mentre il tema della vittima murata nelle cantine ritorna in un altro racconto del terrore interamente privo di elementi sovrannaturali: Il barilozzo di Amontillado, anch’esso (come La maschera della Morte Rossa) di ambientazione genericamente italiana. Ma, se ne La maschera della Morte Rossa il soggetto può essergli stato ispirato dalla situazione iniziale del Decameron di Boccaccio (la “peste nera” del 1348 e la “lieta brigata” dei giovani fiorentini), qui il tema dominante è la vendetta, lucida e spietata, freddamente covata per anni e dissimulata al fine di poter meglio soprendere l’avversario, che da carnefice diventa vittima impotente (con un totale rovesciamento di ruoli rispetto alla situazione precedente, di cui pochissimo viene detto al lettore). Epica e moralistica è dunque l’ispirazione dell’altro racconto, psicologica e “banale” – della banalità del Male, appunto – quella di quest’ultimo.

Montrésor decide di vendicarsi delle lunghe offese di Fortunato; e un giorno, durante il carnevale, lo conduce, semi-ubriaco, a visitare le cantine del suo palazzo, con la scusa di mostrargli un prezioso barilozzo di Amontillado, poiché lo sa esigente intenditore di vini. Giunto nella parte più profonda dei sotterranei, lo ammanetta alle catene predisposte sulla parete, quindi inizia a disporre i mattoni con la calce, strato su strato, in maniera da murarlo vivo, lentamente, nel buio. Fortunato, che è vestito da giullare, scuote i campanelli del suo berretto nel fremito di orrore, quando comincia a rendersi conto che Montrésor non sta affatto scherzando, e che – nel giro di pochi minuti – si troverà sepolto vivo, nell’oscurità totale, destinato a una lunga, orribile agonia, mentre nessuno saprà mai cosa gli è accaduto.

“Era ormai mezzanotte, e la mia opera stava per terminare. Avevo completato l’ottavo, il nono e il decimo strato. Avevo finita una parte dell’undicesimo e ultimo; non mi restava più a commettere e cementare che una sola pietra. Lottavo con il suo peso; la posai parzialmente nel suo posto designato. Ma ecco giungermi dalla nicchia un riso sommesso che mi fece rizzare i capelli in capo. A questo seguì una voce triste che ebbi difficoltà a riconoscere per quella del nobile Fortunato. La voce diceva:

” – Ah! Ah! Ah! Ih! Ih! Ih! Gran bello scherzo davvero: una beffa magnifica. Ne faremo di risate a questo proposito al palazzo: Ih! Ih! Ih! A proposito del nostro vino… Ih! Ih! Ih!

” – L’Amontillado -, dissi.

” – Ih! Ih! Ih! Ih! Ih! Ih! Già, l’Amontillado. Ma non si sta facendo tardi? Non ci staranno aspettando al palazzo, madonna Fortunato e gli altri? Andiamocene.

“- Già – dissi -, andiamocene.

“- Per l’amor di Dio, Montrésor!

” – Già – ripetei -, per l’amor di Dio!

“Ma attesi invano una risposta a queste parole. Divenni impaziente… chiamai forte…

“- Fortunato!

“Nessuna risposta. Chiamai di nuovo…

“- Fortunato!

“Ancora nessuna risposta. Infilai una torcia nel piccolo vano rimasto aperto e la lasciai cadere nell’interno. Mi giunse in risposta soltanto un tintinnio di campanelli. Il mio cuore ebbe un brivido: era l’umidità delle catacombe che produceva in me questo effetto. Mi affrettai a terminare la mia bisogna. A forza spinsi in sito l’ultima pietra e la cementai. Contro la nuova opera murararia reinnalzai l’antico contrafforte d’ossa. Da mezzo secolo nessuna creatura mortale le ha più disturbate. In pace requiescant.”

Ancora la vendetta, una vendetta feroce, disumana, è al centro di un altro racconto che alcuni considerano uno dei migliore del Poe “nero”: Hop Frog. È la storia di come un nano buffone si vendica di uno sgarbo del suo re, inducendolo a travestirsi da scimmione, insieme ai suoi dodici consiglieri, e poi li fa bruciare vivi mentre ruotano, sospesi a una sorta di giostra di legno che gira in circolo, sotto gli occhi di tutta la corte. A noi non pare un racconto degno del miglior Poe: e non perché vi manchino l’elemento soprannaturale o, genericamente, l’elemento del mistero, ma perché si tratta semplicemente di una storia orribile, descritta con noiosa pedanteria, in cui la sproporzione fra l’offesa ricevuta dal nano (anzi, da una sua amica) e la vendetta da lui consumata è talmente abissale da suscitare ripugnanza e disgusto nel lettore. Non si tratta di un’offesa o di una minaccia immaginaria (come ne Il cuore rivelatore), ciò che renderebbe interessante la psicologia del delitto; il nano di Hop Frog è una creatura malvagia che non ha nulla di patologico e nulla di demoniaco: è semplicemente un essere umano capace di serbare un immenso rancore e di attuare lucidamente una rivalsa che va al di là di ogni immaginazione, dopo di che, riesce a farla franca, fuggendo per i tetti. Non vi è il senso di una giustizia divina, come ne La maschera della morte rossa, e non vi è possibilità di una catarsi, per quanto remota, attraverso l’espiazione del male fatto, come ne Il gatto nero. È il trionfo del male puro e semplice, senza insegnamenti per alcuno, senza una morale; di una intelligenza sottile e tortuosa, cui unico scopo è placare il ressentiment di un orgoglio ferito da parte dell’inferiore verso il superiore. È, lo ripetiamo, una vuota storia orribile, non una storia dell’orrore; il piano di guerra del nano feroce è descritto con fastidiosa meticolosità, ma senza il lampo di genio che aveva fatto del protagonista de Il cuore rivelatore un’anima infelice, tormentata ed estremamente interessante.

Concludiamo queste riflessioni sull’opera di Edgar Allan Poe riportando una riflessione del suo biografo Philip Lindsay: “Tormentato nell’anima, cercò non la pace ma l’infelicità, creando a se stesso situazioni disperate, solitudine e desolazione”. Poe, infatti, non fa morire i suoi personaggi per poter, lui, sopravvivere; non li fa seppellire vivi per morire con loro e poi risorgere, metaforicamente: egli si getta a capofitto negli orrori che sa evocare con mano abilissima, quasi pervaso da un’ansia di punizione e di auto-distruzione. E la sua misera morte, in stato di delirium tremens, dopo che lo avevano raccolto – incosciente – per le vie di Baltimora, ai primi di ottobre 1849, ha il sapore di una catastrofe annunciata. Probabilmente, era stato drogato o ubriacato da una squadra di reclutatori di voti per le elezioni politiche in corso, che poi lo aveva abbandonato privo di conoscenza; ma, in un senso più profondo, quella morte egli l’aveva a lungo cercata – con terrore, ma anche con desiderio. Pochi istanti prima di spirare, si era levato sul letto d’ospedale e aveva pronunciato, come fra sé, queste sole, brevi parole: “Oh signore, aiuta la mia povera anima!”. Forse non aveva trovato la risposta alle sue molte domande, ma aveva infine trovato la pace per il suo spirito tormentato.

* * *

Conferenza tenuta dall’Autore a Oderzo, il 16 marzo 2007, nel Palazzo Foscolo (via Garibaldi, 80), nell’ambito delle manifestazioni di “Oderzoinquieta” (9 marzo-29 aprile 2007), a cura della Fondazione Oderzo Cultura e del Comune di Oderzo.

Roy Campbell was born in October 1902 in the Natal District of South Africa. He enjoyed an idyllic childhood, growing up in South Africa and being imbued as much with Zulu traditions and language as with his Scottish heritage. He showed early talent as an artist but an interest in literature including poetry soon became predominant.

Roy Campbell was born in October 1902 in the Natal District of South Africa. He enjoyed an idyllic childhood, growing up in South Africa and being imbued as much with Zulu traditions and language as with his Scottish heritage. He showed early talent as an artist but an interest in literature including poetry soon became predominant.

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Dicevamo della lucidità, della “scientificità”della poetica del Nostro: ebbene, coloro che si son presi la briga di riportare sulla carta geografica la rotta della nave di Gordon Pym attraverso gli oceani, hanno avuto una sorpresa: congiungendone i punti, appariva nettamente la sagoma di un grande uccello con le ali spiegate – come i misteriosi uccelli bianchi che gridano il loro incessante Tekeli-li. Un caso, una semplice coincidenza? Ma Poe amava moltissimo i giochi di decrittazione, gli enigmi logici e linguistici: sempre nel

Dicevamo della lucidità, della “scientificità”della poetica del Nostro: ebbene, coloro che si son presi la briga di riportare sulla carta geografica la rotta della nave di Gordon Pym attraverso gli oceani, hanno avuto una sorpresa: congiungendone i punti, appariva nettamente la sagoma di un grande uccello con le ali spiegate – come i misteriosi uccelli bianchi che gridano il loro incessante Tekeli-li. Un caso, una semplice coincidenza? Ma Poe amava moltissimo i giochi di decrittazione, gli enigmi logici e linguistici: sempre nel  L’incubo della sepoltura da vivi è esplicitamente al centro del racconto Le esequie premature (come lo sarà in altri racconti, tra i quali Berenice, Ligeia e Il crollo della Casa Usher). Nella parte introduttiva di quest’opera, Poe sviluppa alcune riflessioni che potremmo definire filosofiche circa la difficoltà di delimitare con chiarezza la “zona grigia” che separa il regno della vita dal dominio della morte (precorrendo una analoga riflessione dell’epistemologo franco-polacco Mirko Grzimek, che alla morte e alla malattia ha dedicato, sul finire del Novecento, alcuni studi ormai entrati fra i classici del genere).

L’incubo della sepoltura da vivi è esplicitamente al centro del racconto Le esequie premature (come lo sarà in altri racconti, tra i quali Berenice, Ligeia e Il crollo della Casa Usher). Nella parte introduttiva di quest’opera, Poe sviluppa alcune riflessioni che potremmo definire filosofiche circa la difficoltà di delimitare con chiarezza la “zona grigia” che separa il regno della vita dal dominio della morte (precorrendo una analoga riflessione dell’epistemologo franco-polacco Mirko Grzimek, che alla morte e alla malattia ha dedicato, sul finire del Novecento, alcuni studi ormai entrati fra i classici del genere). Il binomio Eros-Thanatos si colora qui di evidenti tracce di sadismo e di inconscia necrofilia, poiché desiderare l’affrettarsi della morte di Morella significa anche pregustare il momento in cui ella non sarà che un corpo abbandonato, indifeso, un corpo interamente alla mercé del maschio: così come il corpo di Pentesilea, dopo essere stato trafitto a morte, accende il desiderio di Achille sotto le mura di Troia, e lo spinge all’estremo oltraggio della sua postuma bellezza.

Il binomio Eros-Thanatos si colora qui di evidenti tracce di sadismo e di inconscia necrofilia, poiché desiderare l’affrettarsi della morte di Morella significa anche pregustare il momento in cui ella non sarà che un corpo abbandonato, indifeso, un corpo interamente alla mercé del maschio: così come il corpo di Pentesilea, dopo essere stato trafitto a morte, accende il desiderio di Achille sotto le mura di Troia, e lo spinge all’estremo oltraggio della sua postuma bellezza. Le Magazine littéraire consacrait jadis un dossier à l’ennui (n° 400, juillet – août 2001) sous le titre : « Éloge de l’ennui. Un mal nécessaire ». En d’autres termes, il s’agissait d’une interrogation sur la positivité de l’ennui au travers une enquête sur l’ennui au travers le travail de divers écrivains, notamment Flaubert, Proust, Pascal, Beckett, Moravia, Cioran.

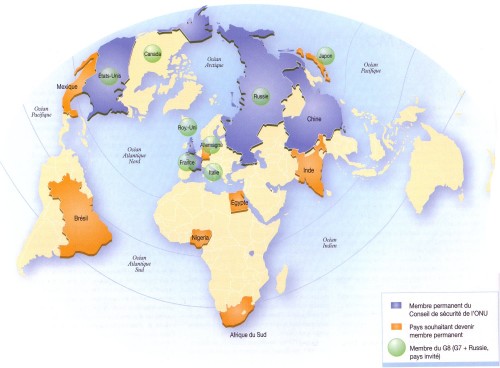

Le Magazine littéraire consacrait jadis un dossier à l’ennui (n° 400, juillet – août 2001) sous le titre : « Éloge de l’ennui. Un mal nécessaire ». En d’autres termes, il s’agissait d’une interrogation sur la positivité de l’ennui au travers une enquête sur l’ennui au travers le travail de divers écrivains, notamment Flaubert, Proust, Pascal, Beckett, Moravia, Cioran. Depuis la fin des deux guerres mondiales et leur débauche de violences, l’Europe est « entrée en dormition » (1). Les Européens ne le savent pas. Tout est fait pour leur masquer cette réalité. Pourtant cet état de « dormition » n’a pas cessé de peser. Jour après jour, se manifeste l’impuissance européenne. La démonstration en a été assénée une nouvelle fois durant la crise de la zone Euro au printemps 2010, prouvant des divergences profondes et l’incapacité d’une volonté politique unanime. La preuve de notre « dormition » est tout aussi visible en Afghanistan, dans le rôle humiliant de forces supplétives assigné aux troupes européennes à la disposition des États-Unis (OTAN).

Depuis la fin des deux guerres mondiales et leur débauche de violences, l’Europe est « entrée en dormition » (1). Les Européens ne le savent pas. Tout est fait pour leur masquer cette réalité. Pourtant cet état de « dormition » n’a pas cessé de peser. Jour après jour, se manifeste l’impuissance européenne. La démonstration en a été assénée une nouvelle fois durant la crise de la zone Euro au printemps 2010, prouvant des divergences profondes et l’incapacité d’une volonté politique unanime. La preuve de notre « dormition » est tout aussi visible en Afghanistan, dans le rôle humiliant de forces supplétives assigné aux troupes européennes à la disposition des États-Unis (OTAN).

The concept of right-wing anarchism seems paradoxical, indeed oxymoronic, starting from the assumption that all “right-wing” political viewpoints include a particularly high evaluation of the principle of order. . . . In fact right-wing anarchism occurs only in exceptional circumstances, when the hitherto veiled affinity between anarchism and conservatism may become apparent.

The concept of right-wing anarchism seems paradoxical, indeed oxymoronic, starting from the assumption that all “right-wing” political viewpoints include a particularly high evaluation of the principle of order. . . . In fact right-wing anarchism occurs only in exceptional circumstances, when the hitherto veiled affinity between anarchism and conservatism may become apparent. The enduring fame of German psychotherapist Hans Prinzhorn (1886–1933) is based almost entirely upon one book, Bildnerei der Geisteskranken (Artistry of the mentally ill), that brilliant and quite unprecedented monograph on the artistic productions of the mentally ill, which appeared in 1922. Sadly, it is too often forgotten that Hans Prinzhorn was the most brilliant and independent disciple of Germany’s greatest 20th-Century philosopher, Ludwig Klages (1872–1956).

The enduring fame of German psychotherapist Hans Prinzhorn (1886–1933) is based almost entirely upon one book, Bildnerei der Geisteskranken (Artistry of the mentally ill), that brilliant and quite unprecedented monograph on the artistic productions of the mentally ill, which appeared in 1922. Sadly, it is too often forgotten that Hans Prinzhorn was the most brilliant and independent disciple of Germany’s greatest 20th-Century philosopher, Ludwig Klages (1872–1956).