La concretezza geopolitica del diritto in Carl Schmitt

La produzione teorica di Carl Schmitt è caratterizzata dalla tendenza dell’autore a spaziare in diversi settori di ricerca e dal rifiuto di assolutizzare un solo fattore o ambito vitale. Nonostante gli siano state rivolte frequenti accuse di ambiguità e asistematicità metodologica – in particolar modo da chi sostiene la “purezza” della scienza del diritto -, in una delle sue ultime interviste, rilasciata nella natia Plettenberg, Schmitt ribadì senza mezzi termini la sua radicale scelta esistenziale: «Mi sento al cento per cento giurista e niente altro. E non voglio essere altro. Io sono giurista e lo rimango e muoio come giurista e tutta la sfortuna del giurista vi è coinvolta» (Lanchester, 1983, pp. 5-34).

Un metodo definito sui generis, distante dalle asettiche teorizzazioni dei fautori del diritto positivo ma non per questo meno orientato alla scienza giuridica, sviscerata fin nelle sue pieghe più riposte per ritrovarne la genesi violenta e i caratteri concreti ed immediati, capaci di imporsi su una realtà che, da “fondamento sfondato”, è minacciata dal baratro del nulla.

In quest’analisi si cercherà di far luce sul rapporto “impuro” tra diritto ed altre discipline, in primis quella politica attraverso cui il diritto stesso si realizza concretamente, e sui volti che questo ha assunto nel corso della sua produzione.

1. Il pensiero di Schmitt può essere compreso solo se pienamente contestualizzato nell’epoca in cui matura: è dunque doveroso affrontarne gli sviluppi collocandoli in prospettiva diacronica, cercando di individuare delle tappe fondamentali ma evitando rigide schematizzazioni.

Si può comunque affermare con una certa sicurezza che attorno alla fine degli anni ’20 le tesi schmittiane subiscano un’evoluzione da una prima fase incentrata sulla “decisione” a una seconda che volge invece agli “ordini concreti”, per una concezione del diritto più ancorata alla realtà e svincolata non solo dall’eterea astrattezza del normativismo, ma pure dallo “stato d’eccezione”, assenza originaria da cui il diritto stesso nasce restando però co-implicato in essa.

L’obiettivo di Schmitt è riportare il diritto alla sfera storica del Sein – rivelando il medesimo attaccamento all’essere del suo amico e collega Heidegger -, che si oppone non solo al Sollen del suo idolo polemico, Hans Kelsen, ma pure al Nicht-Sein, allo spettro del “Niente” che sopravviveva nell’eccezione, volutamente non esorcizzato ma troppo minaccioso per realizzare una solida costruzione giuridica. La “decisione”, come sottolineò Löwith – che accusò Schmitt di “occasionalismo romantico” – non può pertanto essere un solido pilastro su cui fondare il suo impianto teoretico, essendo essa stessa infondata e slegata «dall’energia di un integro sapere sulle origini del diritto e della giustizia» (Löwith, 1994, p.134). Il decisionismo appariva in precedenza come il tentativo più realistico per creare ordine dal disordine, nell’epoca della secolarizzazione e dell’eclissi delle forme di mediazione: colui che s’impone sullo “stato d’eccezione” è il sovrano, che compie un salto dall’Idea alla Realtà. Quest’atto immediato e violento ha sul piano giuridico la stessa valenza di quella di Dio nell’ambito teologico, tanto da far affermare a Schmitt che «tutti i concetti più pregnanti della moderna dottrina dello Stato sono concetti teologici secolarizzati» (Teologia politica, 1972, p.61). Solo nell’eccezione il problema della sovranità si pone come reale e ineludibile, nelle vesti di chi decide sull’eventuale sospensione dell’ordinamento, ponendosi così sia fuori che dentro di esso. Questa situazione liminale non è però metagiuridica: la regola, infatti, vive «solo nell’eccezione» (Ivi, p.41) e il caso estremo rende superfluo il normativo.

La debolezza di tale tesi sta nel fissarsi su una singola istanza, la “decisione”, che ontologicamente è priva di fondamento, in quanto il soggetto che decide – se si può definire tale – è assolutamente indicibile ed infondabile se non sul solo fatto di essere riuscito a decidere e manifestarsi con la decisione. Contrariamente a quanto si potrebbe pensare, decisionismo non è dunque sinonimo di soggettivismo: a partire dalla consapevolezza della sua ambiguità concettuale, Schmitt rivolge la sua attenzione verso la concretezza della realtà storica, che diviene il perno della sua produzione giuridica.

Un cambio di rotta dovuto pure all’erosione della forma-Stato, evidente nella crisi della ”sua” Repubblica di Weimar. Il decisionismo rappresentava un sostrato teorico inadeguato per l’ordinamento giuridico internazionale post-wesfaliano, in cui il tracollo dello Stato[1] spinge Schmitt a individuare nel popolo e nei suoi “ordinamenti concreti” la nuova sede del “politico”.

Arroccato su posizioni anti-universaliste, l’autore elabora tesi che vanno rilette in sostanziale continuità con quelle precedenti ma rielaborate in modo tale da non applicare la prospettiva decisionista a tale paradigma cosmopolitico.

2. Il modello di teoria giuridica che Schmitt approfondì in questa tappa cruciale del suo itinerario intellettuale è l’istituzionalismo di Maurice Hauriou e Santi Romano, che condividono la definizione del diritto in termini di “organizzazione”. La forte coincidenza tra organizzazione sociale e ordinamento giuridico, accompagnata alla serrata critica del normativismo, esercitò una notevole influenza su Schmitt, che ne vedeva il “filo di Arianna” per fuoriuscire dal caos in cui era precipitato il diritto dopo la scomparsa degli Stati sovrani.

Convinto fin dalle opere giovanili che fosse il diritto a creare lo Stato, la crisi irreversibile di quest’ ultimo indusse l’autore a ricercarne gli elementi essenziali all’interno degli “ordinamenti concreti”. Tralasciando la dottrina di Hauriou, che Schmitt studiò con interesse ma che esula da un’analisi prettamente giuridica in quanto fin troppo incentrata sul piano sociologico, è opportuno soffermarsi sull’insegnamento romaniano e sulle affinità tra questi e il tardo pensiero del Nostro. Il giurista italiano riconduceva infatti il concetto di diritto a quello di società – corrispondono al vero sia l’assunto ubi societas ibi ius che ubi ius ibi societas – dove essa costituisca un’«unità concreta, distinta dagli individui che in essa si comprendono» (Romano, 1946, p.15) e miri alla realizzazione dell’«ordine sociale», escludendo quindi ogni elemento riconducibile all’arbitrio o alla forza. Ciò implica che il diritto prima di essere norma è «organizzazione, struttura, posizione della stessa società in cui si svolge e che esso costituisce come unità» (Ivi, p.27).

La coincidenza tra diritto e istituzione seduce Schmitt, al punto da fargli considerare questa particolare teoria come un’alternativa al binomio normativismo/decisionismo, “terza via” di fronte al crollo delle vecchie certezze del giusnaturalismo e alla vulnerabilità del positivismo. Già a partire da Teologia politica il pensiero di matrice kelseniana era stato demolito dall’impianto epistemologico che ruotava intorno ai concetti di sovranità e decisione, che schiacciano il diritto nella sfera del Sein riducendo il Sollen a «modus di rango secondario della normalità» (Portinaro, 1982, p. 58). Il potere della volontà esistenzialmente presente riposa sul suo essere e la norma non vale più in quanto giusta, tramontato il paradigma giusnaturalistico, ma perché è stabilita positivamente, di modo che la coppia voluntas/auctoritas prevalga su quella ratio/veritas.

L’eclissi della decisione osservabile dai primi scritti degli anni ’30 culmina col saggio I tre tipi di pensiero giuridico, in cui al “nemico” scientifico rappresentato dall’astratto normativista Schmitt non oppone più l’eroico decisionista del caso d’eccezione quanto piuttosto il fautore dell’ “ordinamento concreto”, anch’esso ubicato nella sfera dell’essere di cui la normalità finisce per rappresentare un mero attributo, deprivato di quei connotati di doverosità che finirebbero per contrapporsi a ciò che è esistenzialmente dato. Di qui la coloritura organicistico-comunitaria delle istituzioni che Schmitt analizza, sottolineando che «esse hanno in sé i concetti relativi a ciò che è normale» (I tre tipi di pensiero giuridico, 1972, pp.257-258) e citando a mo’ di esempi modelli di ordinamenti concreti come il matrimonio, la famiglia, la chiesa, il ceto e l’esercito.

Il normativismo viene attaccato per la tendenza a isolare e assolutizzare la norma, ad astrarsi dal contingente e concepire l’ordine solo come «semplice funzione di regole prestabilite, prevedibili, generali» (Ibidem). Ma la novità più rilevante da cogliere nel suddetto saggio è il sotteso allontanamento dall’elemento decisionistico, che rischia di non avere più un ruolo nell’ambito di una normalità dotata di una tale carica fondante.

3. L’idea di diritto che l’autore oppone sia alla norma che alla decisione è legata alla concretezza del contesto storico, in cui si situa per diventare ordinamento e da cui è possibile ricavare un nuovo nomos della Terra dopo il declino dello Stato-nazione.

Lo Schmitt che scrive negli anni del secondo conflitto mondiale ha ben presente la necessità di trovare un paradigma ermeneutico della politica in grado di contrastare gli esiti della modernità e individuare una concretezza che funga da katechon contro la deriva nichilistica dell’età della tecnica e della meccanizzazione – rappresentata sul piano dei rapporti internazionali dall’universalismo di stampo angloamericano.

Sulla scia delle suggestioni ricavate dall’istituzionalismo, il giurista è consapevole che solo la forza di elementi primordiali ed elementari può costituire la base di un nuovo ordine.

La teoria del nomos sarà l’ultimo nome dato da Schmitt alla genesi della politica, che ormai lontana dagli abissi dello “stato d’eccezione” trova concreta localizzazione nello spazio e in particolare nella sua dimensione tellurica: i lineamenti generali delle nuove tesi si trovano già in Terra e mare del 1942 ma verranno portati a compimento solo con Il nomos della terra del 1950.

La teoria del nomos sarà l’ultimo nome dato da Schmitt alla genesi della politica, che ormai lontana dagli abissi dello “stato d’eccezione” trova concreta localizzazione nello spazio e in particolare nella sua dimensione tellurica: i lineamenti generali delle nuove tesi si trovano già in Terra e mare del 1942 ma verranno portati a compimento solo con Il nomos della terra del 1950.

Nel primo saggio, pubblicato in forma di racconto dedicato alla figlia Anima, il Nostro si sofferma sull’arcana e mitica opposizione tra terra e mare, caratteristica di quell’ordine affermatosi nell’età moderna a partire dalla scoperta del continente americano. La spazializzazione della politica, chiave di volta del pensiero del tardo Schmitt, si fonda sulla dicotomia tra questi due elementi, ciascuno portatore di una weltanschauung e sviscerati nelle loro profondità ancestrali e mitologiche più che trattati alla stregua di semplici elementi naturali. Il contrasto tra il pensiero terrestre, portatore di senso del confine, del limite e dell’ordine, e pensiero marino, che reputa il mondo una tabula rasa da percorrere e sfruttare in nome del principio della libertà, ha dato forma al nomos della modernità, tanto da poter affermare che «la storia del mondo è la storia della lotta delle potenze terrestri contro le potenze marine» (Terra e mare, 2011, p.18) . Un’interpretazione debitrice delle suggestioni di Ernst Kapp e di Hegel e che si traduceva nel campo geopolitico nel conflitto coevo tra Germania e paesi anglosassoni.

Lo spazio, cardine di quest’impianto teorico, viene analizzato nella sua evoluzione storico-filosofica e con riferimenti alle rivoluzioni che hanno cambiato radicalmente la prospettiva dell’uomo. La modernità si apre infatti con la scoperta del Nuovo Mondo e dello spazio vuoto d’oltreoceano, che disorienta gli europei e li sollecita ad appropriarsi del continente, dividendosi terre sterminate mediante linee di organizzazione e spartizione. Queste rispondono al bisogno di concretezza e si manifestano in un sistema di limiti e misure da inserire in uno spazio considerato ancora come dimensione vuota. È con la nuova rivoluzione spaziale realizzata dal progresso tecnico – nato in Inghilterra con la rivoluzione industriale – che l’idea di spazio esce profondamente modificata, ridotta a dimensione “liscia” e uniforme alla mercé delle invenzioni prodotte dall’uomo quali «elettricità, aviazione e radiotelegrafia», che «produssero un tale sovvertimento di tutte le idee di spazio da portare chiaramente (…) a una seconda rivoluzione spaziale» (Ivi, p.106). Schmitt si oppone a questo cambio di rotta in senso post-classico e, citando la critica heideggeriana alla res extensa, riprende l’idea che è lo spazio ad essere nel mondo e non viceversa. L’originarietà dello spazio, tuttavia, assume in lui connotazioni meno teoretiche, allontanandosi dalla dimensione di “datità” naturale per prendere le forme di determinazione e funzione del “politico”. In questo contesto il rapporto tra idea ed eccezione, ancora minacciato dalla “potenza del Niente” nella produzione precedente, si arricchisce di determinazioni spaziali concrete, facendosi nomos e cogliendo il nesso ontologico che collega giustizia e diritto alla Terra, concetto cardine de Il nomos della terra, che rappresenta per certi versi una nostalgica apologia dello ius publicum europaeum e delle sue storiche conquiste. In quest’opera infatti Schmitt si sofferma nuovamente sulla contrapposizione terra/mare, analizzata stavolta non nei termini polemici ed oppositivi di Terra e mare[2] quanto piuttosto sottolineando il rapporto di equilibrio che ne aveva fatto il cardine del diritto europeo della modernità. Ma è la iustissima tellus, «madre del diritto» (Il nomos della terra, 1991, p.19), la vera protagonista del saggio, summa del pensiero dell’autore e punto d’arrivo dei suoi sforzi per opporre un solido baluardo al nichilismo.

Nel nomos si afferma l’idea di diritto che prende la forma di una forza giuridica non mediata da leggi che s’impone con violenza sul caos. La giustizia della Terra che si manifesta nel nomos è la concretezza di un arbitrio originario che è principio giuridico d’ordine, derivando paradossalmente la territorialità dalla sottrazione, l’ordine dal dis-ordine. Eppure, nonostante s’avverta ancora l’eco “tragica” degli scritti giovanili, il konkrete Ordnung in cui si esprime quest’idea sembra salvarlo dall’infondatezza e dall’occasionalismo di cui erano state accusate le sue teorie precedenti.

Da un punto di vista prettamente giuridico, Schmitt ribadisce la sentita esigenza di concretezza evitando di tradurre il termine nomos con “legge, regola, norma”, triste condanna impartita dal «linguaggio positivistico del tardo secolo XIX» (Ivi, p.60). Bisogna invece risalire al significato primordiale per evidenziarne i connotati concreti e l’origine abissale, la presa di possesso e di legittimità e al contempo l’assenza e l’eccedenza. La catastrofe da cui lo ius publicum europaeum è nato, ossia la fine degli ordinamenti pre-globali, è stata la grandezza del moderno razionalismo politico, capace di avere la propria concretezza nell’impavida constatazione della sua frattura genetica e di perderla con la riduzione del diritto ad astratta norma. Ed è contro il nichilismo del Gesetz che Schmitt si arma, opponendo alla sua “mediatezza”, residuo di una razionalità perduta, l’“immediatezza” del nomos, foriero di una legittimità che «sola conferisce senso alla legalità della mera legge» (Ivi, p.63).

GEOPOLITICA & TEORIA 27/05/2015 Ugo Gaudino

BIBLIOGRAFIA ESSENZIALE

AMENDOLA A., Carl Schmitt tra decisione e ordinamento concreto, Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane, Napoli, 1999

CARRINO A., Carl Schmitt e la scienza giuridica europea, introduzione a C. SCHMITT, La condizione della scienza giuridica europea, Pellicani Editore, Roma, 1996

CASTRUCCI E., Introduzione alla filosofia del diritto pubblico di Carl Schmitt, Giappichelli, Torino, 1991

ID., Nomos e guerra. Glosse al «Nomos della terra» di Carl Schmitt, La scuola di Pitagora, Napoli, 2011

CATANIA A., Carl Schmitt e Santi Romano, in Il diritto tra forza e consenso, Edizioni Scientifiche Italiane, Napoli, 1990, pp.137-177

CHIANTERA-STUTTE P., Il pensiero geopolitico. Spazio, potere e imperialismo tra Otto e Novecento, Carocci Editore, Roma, 2014

DUSO G., La soggettività in Schmitt in Id., La politica oltre lo Stato: Carl Schmitt, Arsenale, Venezia, 1981, pp.49-68

GALLI C., Genealogia della politica. Carl Schmitt e la crisi del pensiero politico moderno, Il Mulino, Bologna, 2010

LANCHESTER F., Un giurista davanti a sé stesso, in «Quaderni costituzionali», III, 1983, pp. 5-34

LÖWITH K., Il decisionismo occasionale di Carl Schmitt, in Marx, Weber, Schmitt, Laterza, Roma:Bari,1994

PIETROPAOLI S., Ordinamento giuridico e «konkrete Ordnung». Per un confronto tra le teorie istituzionalistiche di Santi Romano e Carl Schmitt, in «Jura Gentium», 2, 2012

ID., Schmitt, Carocci, Roma, 2012

PORTINARO P. P., La crisi dello jus publicum europaeum. Saggio su Carl Schmitt, Edizioni di Comunità, Milano, 1982

ROMANO S., L’ordinamento giuridico, Firenze, Sansoni, 1946

SCHMITT C., Die Diktatur, Duncker & Humblot, Monaco-Lipsia, 1921, trad. it. La dittatura, Laterza, Roma-Bari, 1975

ID., Politische Theologie. Vier Kapitel zur Lehre der Souveränität, Duncker & Humblot, Monaco-Lipsia 1922, trad it. Teologia politica. Quattro capitoli sulla dottrina della sovranità, in Le categorie del ‘politico’ (a cura di P. SCHIERA e G. MIGLIO), Il Mulino, Bologna, 1972

ID., Verfassungslehre, Duncker & Humblot, Monaco-Lipsia 1928, trad. it. Dottrina della costituzione, Giuffrè, Milano, 1984

ID., Der Begriff des Politischen, in C. SCHMITT et al., Probleme der Demokratie, Walther Rothschild, Berlino-Grunewald, 1928, pp. 1-34, trad. it. Il concetto di ‘politico’. Testo del 1932 con una premessa e tre corollari, in Le categorie del ‘politico’, Il Mulino, Bologna, 1972

ID., Legalität und Legitimität, Duncker & Humblot, Monaco-Lipsia 1932, trad. it. Legalità e legittimità, in Le categorie del ‘politico’, Il Mulino, Bologna, 1972

ID., Über die drei Arten des rechtswissenschaftlichen Denkens, Hanseatische Verlagsanstaldt, Amburgo, 1934, trad. it. I tre tipi di pensiero giuridico, in Le categorie del ‘politico’, Il Mulino, Bologna, 1972

ID., Land und Meer. Eine weltgeschichtliche Betrachtung, Reclam, Lipsia 1942, trad. it. Terra e mare. Una considerazione sulla storia del mondo raccontata a mia figlia Anima, Adelphi, 2011

ID., Der Nomos der Erde im Völkerrecht des Jus Publicum europaeum, Greven, Colonia 1950, trad. it. Il Nomos della terra nel diritto internazionale dello “ius publicum europaeum”, Adelphi, Milano, 1991

ID., Die Lage der europäischen Rechtswissenschaft, Internationaler Universitätsverlag, Tubinga, 1950, trad. it. La condizione della scienza giuridica europea, Pellicani Editore, Roma, 1996

EM : Avez-vous eu d’autres influences ? Julius Evola semble vous avoir fortement influencé ?

EM : Avez-vous eu d’autres influences ? Julius Evola semble vous avoir fortement influencé ?

del.icio.us

del.icio.us

Digg

Digg

Bori Nad (Serbia):

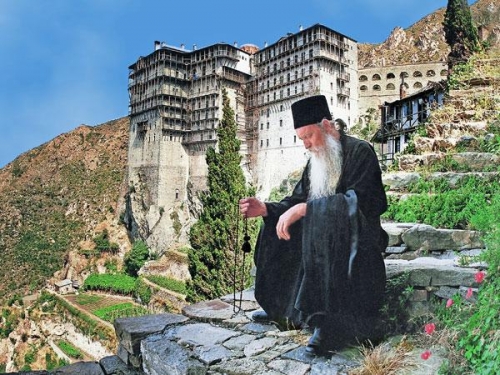

Bori Nad (Serbia):  Después de la caída del Imperio Romano, existió la conocida "translatio imperii ad Francos" y más tarde, después de la Batalla de Lechfeld en 955, una "translatio imperii ad Germanos". La parte central de Europa se convirtió así en el núcleo del Imperio, estando ahora centrada en el Rin, el Ródano y el Po. El eje del Danubio se cortó al nivel de las "Puertas de hierro", más allá del cual el área bizantina se extendía hacia el este. El Imperio Bizantino fue el heredero directo del Imperio Romano: allí la legitimidad nunca fue disputada. La comunidad del Monte Athos es un centro espiritual que en fecha reciente ha sido plenamente reconocido por el presidente ruso Putin. El Imperio Romano-Germánico (más tarde Austriaco-Húngaro), el Imperio Ruso como heredero de Bizancio y la comunidad religiosa del Monte Athos comparten los mismos símbolos de una bandera dorada con un águila bicéfala negra, remanente de un antiguo culto tradicional persa donde las aves aseguraban el vínculo entre la Tierra y los Cielos, entre los hombres y los dioses. El águila es el ave más majestuosa que vuela en las alturas más elevadas en el cielo, y se convirtió obviamente en el símbolo de la dimensión sagrada del Imperio.

Después de la caída del Imperio Romano, existió la conocida "translatio imperii ad Francos" y más tarde, después de la Batalla de Lechfeld en 955, una "translatio imperii ad Germanos". La parte central de Europa se convirtió así en el núcleo del Imperio, estando ahora centrada en el Rin, el Ródano y el Po. El eje del Danubio se cortó al nivel de las "Puertas de hierro", más allá del cual el área bizantina se extendía hacia el este. El Imperio Bizantino fue el heredero directo del Imperio Romano: allí la legitimidad nunca fue disputada. La comunidad del Monte Athos es un centro espiritual que en fecha reciente ha sido plenamente reconocido por el presidente ruso Putin. El Imperio Romano-Germánico (más tarde Austriaco-Húngaro), el Imperio Ruso como heredero de Bizancio y la comunidad religiosa del Monte Athos comparten los mismos símbolos de una bandera dorada con un águila bicéfala negra, remanente de un antiguo culto tradicional persa donde las aves aseguraban el vínculo entre la Tierra y los Cielos, entre los hombres y los dioses. El águila es el ave más majestuosa que vuela en las alturas más elevadas en el cielo, y se convirtió obviamente en el símbolo de la dimensión sagrada del Imperio. Crouzet explica en su libro que la Reforma alemana y europea quería "precipitar" las cosas, aspirando al mismo tiempo a experimentar animadamente el "eschaton", el fin del mundo. Esta teología de la precipitación es el primer signo exterior del modernismo. Lutero, de una manera bastante moderada, y los otros actores de la Reforma, de una manera extrema, querían el fin de un mundo (el fin de una continuidad histórica) que consideraban profundamente infectado por el mal.

Crouzet explica en su libro que la Reforma alemana y europea quería "precipitar" las cosas, aspirando al mismo tiempo a experimentar animadamente el "eschaton", el fin del mundo. Esta teología de la precipitación es el primer signo exterior del modernismo. Lutero, de una manera bastante moderada, y los otros actores de la Reforma, de una manera extrema, querían el fin de un mundo (el fin de una continuidad histórica) que consideraban profundamente infectado por el mal.

Hélas, une partie non négligeable des livres de René Guénon ne sont plus disponible, notamment ceux édités par les Éditions Traditionnelles. Il fallait donc chiner chez les libraires ou sur le Net afin de trouver, parfois à des prix prohibitifs, certains ouvrages. Mais ça c’était avant, car les éditons Omnia Veritas (1) viennent de rééditer les dix-sept ouvrages majeurs de René Guénon ainsi que quelques recueils posthumes tels Études sur l’hindouisme (2). C’est un véritable plaisir de redécouvre certains travaux de Guénon comme L’erreur spirite (3), Aperçus sur l’ésotérisme chrétien (4) ou L’homme et son devenir selon le Vêdânta (5) pour un rapport qualité/prix plus que correct.

Hélas, une partie non négligeable des livres de René Guénon ne sont plus disponible, notamment ceux édités par les Éditions Traditionnelles. Il fallait donc chiner chez les libraires ou sur le Net afin de trouver, parfois à des prix prohibitifs, certains ouvrages. Mais ça c’était avant, car les éditons Omnia Veritas (1) viennent de rééditer les dix-sept ouvrages majeurs de René Guénon ainsi que quelques recueils posthumes tels Études sur l’hindouisme (2). C’est un véritable plaisir de redécouvre certains travaux de Guénon comme L’erreur spirite (3), Aperçus sur l’ésotérisme chrétien (4) ou L’homme et son devenir selon le Vêdânta (5) pour un rapport qualité/prix plus que correct.

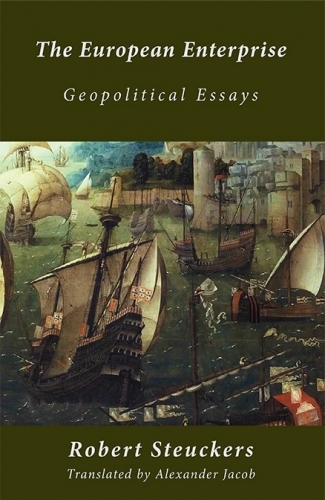

The more radical underlying principles were adapted to the Zeitgeist of the Fifties and the Sixties by think tanks lead ultimately by the OSS (“Office of Strategic Studies”). This created the perverse corpus of May 68 that was launched into Germany and France. Both countries could resist in the Seventies although their societies were all the same contaminated by the bacillus that was eroding gradually their traditional psychological assets. A second wave had to be prepared to give all the Western societies the last blow to let their political bodies crumble down. Next to the May 68 ideology, more or less derived from the Frankfurt School, a new weapon was forged to destroy Europe (and partly the rest of the world) more efficiently. This weapon was the infamous Thatcherite neoliberalism. At the very end of the Seventies, neoliberalism (be it Thatcherism or Reaganomics) was celebrated as a new liberation ideology that was about to get rid of the political State-centered praxis. Neither the Christian democrats nor the social-democrats were able to resist staunchly and to remember their supporters that the Church doctrine (based on Thomas Aquino and Aristoteles) or the interventionist socialist tradition were genuinely hostile to such an unbridled liberalism. Economics became more important than politics. We entered at that very moment the so-called post-history where no marks were still to be found. Even worse, the corrupt “partitocratic” system, in which Christian democrats and social-democrats were painfully muddling through, prevented any rational reaction and any challenge from new parties, blocking the democratic process they so vehemently pretend to incarnate alone.

The more radical underlying principles were adapted to the Zeitgeist of the Fifties and the Sixties by think tanks lead ultimately by the OSS (“Office of Strategic Studies”). This created the perverse corpus of May 68 that was launched into Germany and France. Both countries could resist in the Seventies although their societies were all the same contaminated by the bacillus that was eroding gradually their traditional psychological assets. A second wave had to be prepared to give all the Western societies the last blow to let their political bodies crumble down. Next to the May 68 ideology, more or less derived from the Frankfurt School, a new weapon was forged to destroy Europe (and partly the rest of the world) more efficiently. This weapon was the infamous Thatcherite neoliberalism. At the very end of the Seventies, neoliberalism (be it Thatcherism or Reaganomics) was celebrated as a new liberation ideology that was about to get rid of the political State-centered praxis. Neither the Christian democrats nor the social-democrats were able to resist staunchly and to remember their supporters that the Church doctrine (based on Thomas Aquino and Aristoteles) or the interventionist socialist tradition were genuinely hostile to such an unbridled liberalism. Economics became more important than politics. We entered at that very moment the so-called post-history where no marks were still to be found. Even worse, the corrupt “partitocratic” system, in which Christian democrats and social-democrats were painfully muddling through, prevented any rational reaction and any challenge from new parties, blocking the democratic process they so vehemently pretend to incarnate alone. As the New Right writer Guillaume Faye had previously told it: France in the present-day situation is totally unable to reestablish law and order when riots spread in more than three or four big urban areas. The riots lasted the time needed to promote a new previously obscure petty politician, Nicolas Sarközy, who promised to wipe out the troublemakers in the suburbs and did of course absolutely nothing once in power. Charles Rivkin, US ambassador in France is the theorist of this “4th Generation Warfare” operations aiming at exciting migrant communities against law and order in France (see:

As the New Right writer Guillaume Faye had previously told it: France in the present-day situation is totally unable to reestablish law and order when riots spread in more than three or four big urban areas. The riots lasted the time needed to promote a new previously obscure petty politician, Nicolas Sarközy, who promised to wipe out the troublemakers in the suburbs and did of course absolutely nothing once in power. Charles Rivkin, US ambassador in France is the theorist of this “4th Generation Warfare” operations aiming at exciting migrant communities against law and order in France (see:

Q.:

Q.:

Living within the territorial frames of an Empire means to fulfill a spiritual task: to establish on Earth a similar harmony as the one displayed by the celestial order. The dove symbolizing the Holy Spirit in Christian tradition has indeed the same symbolic task as the eagle in imperial tradition: assuring the link between the Uranic realm (Greek Uranus/Vedic Varuna) and the Earth (Gaia). As the subject of an Empire, I’m compelled to dedicate all my life trying to reach the perfection of the apparently perfect order of the celestial bodies. It’s an ascetic and military duty featured by the archangel Michael, also a figure derived from the man/bird beings of the Persian mythology that the Hebrews brought back from their Babylonian captivity. Emperor Charles V tried to incarnate this Chivalry’s ideal despite the petty human sins he consciously committed during his life. He remained truly human, a sinner, and dedicated all his efforts to keep the Empire alive, to make of it a dam against decay, which is the task of the “katechon” according to Carl Schmitt. No one better than the Frenchman Denis Crouzet has described this perpetual tension the Emperor lived in his marvelous book, Charles Quint, Empereur d’une fin des temps, Odile Jacob, Paris, 2016. I’m reading this very thick book over and over again which will help me to precise my imperial world view and to understand better what Schmitt meant when he considered Church and Empire as ‘katechonical” forces. This chapter is far from being closed.

Living within the territorial frames of an Empire means to fulfill a spiritual task: to establish on Earth a similar harmony as the one displayed by the celestial order. The dove symbolizing the Holy Spirit in Christian tradition has indeed the same symbolic task as the eagle in imperial tradition: assuring the link between the Uranic realm (Greek Uranus/Vedic Varuna) and the Earth (Gaia). As the subject of an Empire, I’m compelled to dedicate all my life trying to reach the perfection of the apparently perfect order of the celestial bodies. It’s an ascetic and military duty featured by the archangel Michael, also a figure derived from the man/bird beings of the Persian mythology that the Hebrews brought back from their Babylonian captivity. Emperor Charles V tried to incarnate this Chivalry’s ideal despite the petty human sins he consciously committed during his life. He remained truly human, a sinner, and dedicated all his efforts to keep the Empire alive, to make of it a dam against decay, which is the task of the “katechon” according to Carl Schmitt. No one better than the Frenchman Denis Crouzet has described this perpetual tension the Emperor lived in his marvelous book, Charles Quint, Empereur d’une fin des temps, Odile Jacob, Paris, 2016. I’m reading this very thick book over and over again which will help me to precise my imperial world view and to understand better what Schmitt meant when he considered Church and Empire as ‘katechonical” forces. This chapter is far from being closed. Crouzet explains in his book that the German and European Reformation wanted to “precipitate” things, aspiring at the same time to experiment lively the “eschaton”, the end of the world. This precipitation theology is the very first outward sign of modernism. Luther in a quite moderate way and the other actors of Reformation in an extreme way wanted the end of a world (of a historical continuity) they considered as profoundly infected by evil. Charles V, explains Crouzet, has an imperial and “katechonical” attitude. As an Emperor and a servant of God on Earth, he has to slow down the “eschaton” process to preserve his subjects from the afflictions of decay.

Crouzet explains in his book that the German and European Reformation wanted to “precipitate” things, aspiring at the same time to experiment lively the “eschaton”, the end of the world. This precipitation theology is the very first outward sign of modernism. Luther in a quite moderate way and the other actors of Reformation in an extreme way wanted the end of a world (of a historical continuity) they considered as profoundly infected by evil. Charles V, explains Crouzet, has an imperial and “katechonical” attitude. As an Emperor and a servant of God on Earth, he has to slow down the “eschaton” process to preserve his subjects from the afflictions of decay. I could add that a “precipitation theology or ideology” doesn’t express itself by all sorts of millennial pseudo-religious babbling claptrap like the one which is predicated for instance in Latin America but can also act as an economic fundamentalism like the neoliberal craze that affects America and Europe since the end of the Seventies. Puritanism can also quite often be reversed in its diametral contrary i. e. postmodernist debauch what explains that millennials, femens, pussy rioters, Salafists, neoliberal “banksters”, media moguls, color revolutionists, etc. follows on the international chessboard the same “4th Generation Warfare” agenda. Aim is to destroy all the dams civilization has set to serve the “Katechon” or the Aristotelian “Spoudaios”. We must define ourselves as the humble servants of the Katechon against the pretentious designs of the “precipitators”. This means serving the imperial powers and fighting the powers that are perverted by the “precipitators”. Or having a Eurasian option and not an Atlanticist one.

I could add that a “precipitation theology or ideology” doesn’t express itself by all sorts of millennial pseudo-religious babbling claptrap like the one which is predicated for instance in Latin America but can also act as an economic fundamentalism like the neoliberal craze that affects America and Europe since the end of the Seventies. Puritanism can also quite often be reversed in its diametral contrary i. e. postmodernist debauch what explains that millennials, femens, pussy rioters, Salafists, neoliberal “banksters”, media moguls, color revolutionists, etc. follows on the international chessboard the same “4th Generation Warfare” agenda. Aim is to destroy all the dams civilization has set to serve the “Katechon” or the Aristotelian “Spoudaios”. We must define ourselves as the humble servants of the Katechon against the pretentious designs of the “precipitators”. This means serving the imperial powers and fighting the powers that are perverted by the “precipitators”. Or having a Eurasian option and not an Atlanticist one. The second Eurasian project avant la lettre was the very short-lived “Holy Alliance” or “Pentarchy” created in the aftermath of the Treaty of Vienna in 1814. It allowed the independence of Greece but failed after the independence of Belgium when England and France helped to destroy the United Kingdom of the Netherlands. The “Holy Alliance” definitively crumbled down when the Crimea War started as two Western powers of the “Pentarchy” clashed with Russia. The Anti-Western affect spread widely in Russia and the core ideas of it are clearly outlined in Dostoyevsky’s main political book, A Writer’s Diary, written after his Siberian exile and the Russian-Turkish War of 1877-78. The West permanently plots against Russia and Russia has to defend itself against these constant endeavors to erode its power and its domestic stability.

The second Eurasian project avant la lettre was the very short-lived “Holy Alliance” or “Pentarchy” created in the aftermath of the Treaty of Vienna in 1814. It allowed the independence of Greece but failed after the independence of Belgium when England and France helped to destroy the United Kingdom of the Netherlands. The “Holy Alliance” definitively crumbled down when the Crimea War started as two Western powers of the “Pentarchy” clashed with Russia. The Anti-Western affect spread widely in Russia and the core ideas of it are clearly outlined in Dostoyevsky’s main political book, A Writer’s Diary, written after his Siberian exile and the Russian-Turkish War of 1877-78. The West permanently plots against Russia and Russia has to defend itself against these constant endeavors to erode its power and its domestic stability.  Peter Frankopan’s book is more factual but also enables to criticize the Western arrogant attitude namely in Iran. The chapters in his book dedicated to old Persia and modern Iran would allow diplomats to settle bases for a renewed cooperation between European powers and Iran, provided, of course, that Europeans really would abandon the guidelines dictated by NATO and the United States. Eurasianism compels you to study history more thoroughly than the present-day Western way of leading policies in the world. Facts shouldn’t be ignored or disregarded simply because they don’t fit into the schemes of the superficial interpretation of the Enlightenment the Western powers are currently handling, provoking at the same time a concatenation of catastrophes.

Peter Frankopan’s book is more factual but also enables to criticize the Western arrogant attitude namely in Iran. The chapters in his book dedicated to old Persia and modern Iran would allow diplomats to settle bases for a renewed cooperation between European powers and Iran, provided, of course, that Europeans really would abandon the guidelines dictated by NATO and the United States. Eurasianism compels you to study history more thoroughly than the present-day Western way of leading policies in the world. Facts shouldn’t be ignored or disregarded simply because they don’t fit into the schemes of the superficial interpretation of the Enlightenment the Western powers are currently handling, provoking at the same time a concatenation of catastrophes.

The German historian Reinhard Schmoeckel hypothezises that even the Merovingians, from whom Chlodowegh (Clovis for the French) descended, were partly Sarmatian and not purely Germanic. In Spain, historians admit that among the Visigoths and the Sueves that invaded the peninsula as Germanic tribes were accompanied by Alans, a horsemen people from the Caspian and Caucasus area. The traditions they brought to Spain are at the origin of the chivalry orders that helped a lot to perform the Reconquista. As you say, all that has been neglected but now things are changing. In my short essay on the geopoliticians in Berlin between both world wars, I remember a poor sympathetic professor who tried to coin a new historiography in Europe taking the Eastern elements into accounts but whose impressive collection of documents were completely destroyed during the battle for Berlin in 1945. His name was Otto Hoetzsch. He was a Slavic philologist, a translator (namely during the negotiations of the Rapallo Treaty, 1922) and a historian of Russia: he pleaded for a common European historiography stressing the convergences and not the differences leading to catastrophic conflicts like the German-Russian wars of the 20th century. I wrote that we all have to walk in his footsteps. I suppose you agree.

The German historian Reinhard Schmoeckel hypothezises that even the Merovingians, from whom Chlodowegh (Clovis for the French) descended, were partly Sarmatian and not purely Germanic. In Spain, historians admit that among the Visigoths and the Sueves that invaded the peninsula as Germanic tribes were accompanied by Alans, a horsemen people from the Caspian and Caucasus area. The traditions they brought to Spain are at the origin of the chivalry orders that helped a lot to perform the Reconquista. As you say, all that has been neglected but now things are changing. In my short essay on the geopoliticians in Berlin between both world wars, I remember a poor sympathetic professor who tried to coin a new historiography in Europe taking the Eastern elements into accounts but whose impressive collection of documents were completely destroyed during the battle for Berlin in 1945. His name was Otto Hoetzsch. He was a Slavic philologist, a translator (namely during the negotiations of the Rapallo Treaty, 1922) and a historian of Russia: he pleaded for a common European historiography stressing the convergences and not the differences leading to catastrophic conflicts like the German-Russian wars of the 20th century. I wrote that we all have to walk in his footsteps. I suppose you agree.

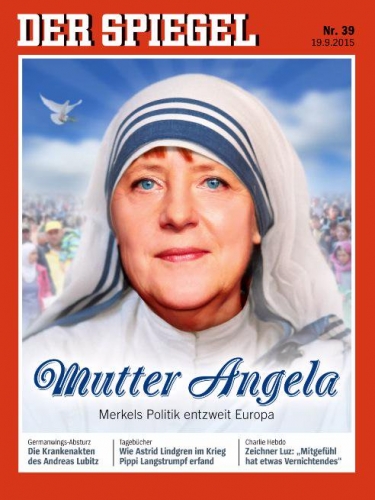

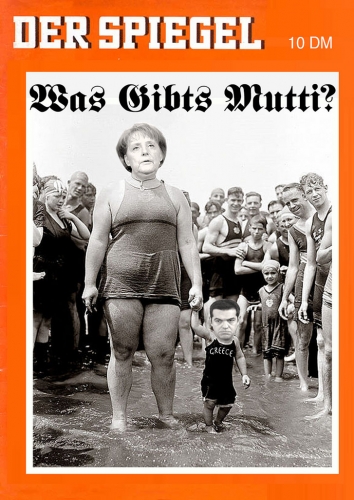

A titre liminaire, notons qu'une telle situation de blocage survenant immédiatement après une élection est bel et bien unique dans l'histoire de l'Allemagne depuis 1949. En revanche, la République fédérale a déjà connu des impasses constitutionnelles comparables et même un gouvernement minoritaire dans les années 1970, comme nous allons le voir plus bas.

A titre liminaire, notons qu'une telle situation de blocage survenant immédiatement après une élection est bel et bien unique dans l'histoire de l'Allemagne depuis 1949. En revanche, la République fédérale a déjà connu des impasses constitutionnelles comparables et même un gouvernement minoritaire dans les années 1970, comme nous allons le voir plus bas. Scénario 3 :

Scénario 3 :  Contrairement à ce que beaucoup peuvent imaginer, l'Allemagne a déjà connu une telle situation en 1972 après que plusieurs élus de la majorité SPD-FDP ont quitté leurs partis respectifs par rejet de l'Ostpolitik menée par Willy Brandt, tandis que l’opposition de droite menée par Rainer Barzel avait échoué à faire adopter à deux voix près sa motion de défiance constructive déposée dans le cadre de l'article 67 de la Loi fondamentale. Brandt continua donc à gouverner sans majorité jusqu'à un retournement de conjoncture politique qu'il exploita en engageant la responsabilité de son gouvernement par le dépôt d'une Motion de confiance (art. 68 LF) dont il savait qu'elle serait rejetée par le Bundestag... ce qui entraîna une dissolution de l'assemblée et une victoire de Brandt à l'élection qui s'ensuivit. Mais dans le cas présent, Angela Merkel a d'ores et déjà fait savoir qu'elle préférait une nouvelle élection que former un gouvernement minoritaire.

Contrairement à ce que beaucoup peuvent imaginer, l'Allemagne a déjà connu une telle situation en 1972 après que plusieurs élus de la majorité SPD-FDP ont quitté leurs partis respectifs par rejet de l'Ostpolitik menée par Willy Brandt, tandis que l’opposition de droite menée par Rainer Barzel avait échoué à faire adopter à deux voix près sa motion de défiance constructive déposée dans le cadre de l'article 67 de la Loi fondamentale. Brandt continua donc à gouverner sans majorité jusqu'à un retournement de conjoncture politique qu'il exploita en engageant la responsabilité de son gouvernement par le dépôt d'une Motion de confiance (art. 68 LF) dont il savait qu'elle serait rejetée par le Bundestag... ce qui entraîna une dissolution de l'assemblée et une victoire de Brandt à l'élection qui s'ensuivit. Mais dans le cas présent, Angela Merkel a d'ores et déjà fait savoir qu'elle préférait une nouvelle élection que former un gouvernement minoritaire.

The narrator, Mizoguchi, is physically weak, ugly in appearance, and afflicted with a stutter. This isolates him from others, and he becomes a solitary, brooding child. He first learns of the Golden Temple from his father, a frail country priest, and the image of the temple and its beauty becomes for him an idée fixe. The young Mizoguchi worships his vision of temple, but there are omens of what is to come. When a naval cadet visits his village and notices his stutter, Mizoguchi is resentful and retaliates by defacing the cadet’s prized scabbard. From the beginning, he realizes that the beauty of the temple represents an unattainable ideal: “if beauty really did exist there, it meant that my own existence was a thing estranged from beauty” (21). Over time, this seed in his mind metastasizes and begins to consume him.

The narrator, Mizoguchi, is physically weak, ugly in appearance, and afflicted with a stutter. This isolates him from others, and he becomes a solitary, brooding child. He first learns of the Golden Temple from his father, a frail country priest, and the image of the temple and its beauty becomes for him an idée fixe. The young Mizoguchi worships his vision of temple, but there are omens of what is to come. When a naval cadet visits his village and notices his stutter, Mizoguchi is resentful and retaliates by defacing the cadet’s prized scabbard. From the beginning, he realizes that the beauty of the temple represents an unattainable ideal: “if beauty really did exist there, it meant that my own existence was a thing estranged from beauty” (21). Over time, this seed in his mind metastasizes and begins to consume him. All human beings possess a will to power in the Nietzschean sense. This finds its highest expression in self-actualization and self-mastery, and in the achievements of great artists, thinkers, and leaders, but in its lower forms is embodied by the desire of defective beings to assert themselves at all costs. This is manifested in Mizoguchi’s desire to destroy the temple, which intensifies in proportion to his realization that he will never be able to possess it or approach its beauty.

All human beings possess a will to power in the Nietzschean sense. This finds its highest expression in self-actualization and self-mastery, and in the achievements of great artists, thinkers, and leaders, but in its lower forms is embodied by the desire of defective beings to assert themselves at all costs. This is manifested in Mizoguchi’s desire to destroy the temple, which intensifies in proportion to his realization that he will never be able to possess it or approach its beauty.

La teoria del nomos sarà l’ultimo nome dato da Schmitt alla genesi della politica, che ormai lontana dagli abissi dello “stato d’eccezione” trova concreta localizzazione nello spazio e in particolare nella sua dimensione tellurica: i lineamenti generali delle nuove tesi si trovano già in Terra e mare del 1942 ma verranno portati a compimento solo con Il nomos della terra del 1950.

La teoria del nomos sarà l’ultimo nome dato da Schmitt alla genesi della politica, che ormai lontana dagli abissi dello “stato d’eccezione” trova concreta localizzazione nello spazio e in particolare nella sua dimensione tellurica: i lineamenti generali delle nuove tesi si trovano già in Terra e mare del 1942 ma verranno portati a compimento solo con Il nomos della terra del 1950.

News of Seth’s victory reaches London where Basil Seal, the ne’er-do-well son of the Conservative Whip and a classmate of Seth’s at Oxford, is recovering from a series of scandalous benders that have forced him to abandon his nascent political career. Desperately in need of money, Seal travels to Azania as a free-lance journalist. Within a short time of his arrival, Basil becomes Seth’s most trusted adviser and is put in charge of the Ministry of Modernization; in effect, Basil has become the real ruler of Azania since Seth spends his time immersed in catalogs and dreaming up more and more ridiculous “progressive” schemes for the betterment of Azanians, such as requiring all citizens to learn Esperanto. The natives who run the other departments are all too happy to refer all business to Basil.

News of Seth’s victory reaches London where Basil Seal, the ne’er-do-well son of the Conservative Whip and a classmate of Seth’s at Oxford, is recovering from a series of scandalous benders that have forced him to abandon his nascent political career. Desperately in need of money, Seal travels to Azania as a free-lance journalist. Within a short time of his arrival, Basil becomes Seth’s most trusted adviser and is put in charge of the Ministry of Modernization; in effect, Basil has become the real ruler of Azania since Seth spends his time immersed in catalogs and dreaming up more and more ridiculous “progressive” schemes for the betterment of Azanians, such as requiring all citizens to learn Esperanto. The natives who run the other departments are all too happy to refer all business to Basil.

•

•